Introduction

Pediatric arrhythmias encompass a diverse array of conditions that present along a broad spectrum-from asymptomatic cases to sporadic or frequent episodes of paroxysmal tachycardia, and even sudden cardiac death (SCD) as the initial manifestation of severe disorders caused by genetic mutations in cardiac ion channels or associated proteins1. Although the literature on cardiac electrical disorders is extensive, research focused on children is relatively sparse. Consequently, the management and treatment protocols often mirror those established for adults, which are underpinned by a more robust body of evidence regarding their efficacy2,3.

Cardiac diseases in both adults and children may exhibit similar morphological and clinical characteristics, yet their prognoses differ markedly. Non-specialist physicians, who are typically the first to engage with affected children, are primarily guided by the presenting symptoms that prompt medical consultations. An initial survey of the literature reveals a significant gap in practical, accessible management guides for non-specialists that comprehensively address the full spectrum of pediatric electrical diseases based on patient symptoms4,5.

This review aimed is to synthesize the present evidence regarding the strategies for approaching and managing pediatric arrhythmias, from the most common and benign to those capable of causing SCD. It seeks to equip non-specialist physicians with a clear and pragmatic guide for treating these conditions, tailored to the observed symptoms in pediatric patients. It is important to clarify that this review focuses on pediatric arrhythmias in the context of a normal heart and in hemodynamically stable patients.

Method

Design

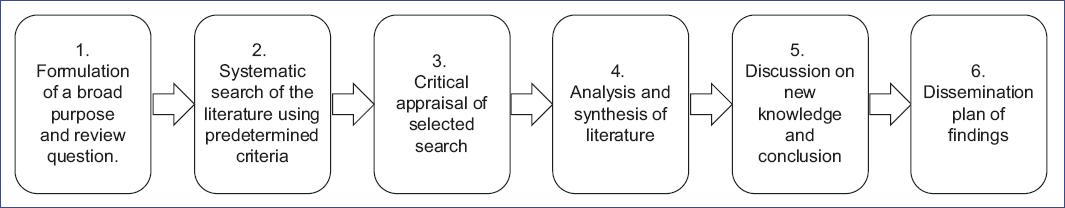

We conducted an integrative review (IR) following Cooper's methodological framework (Fig. 1)6-10. The IR was driven by the central research question: "What are the effective strategies for diagnosing and treating pediatric arrhythmias, ranging from benign to life-threatening conditions, with an emphasis on practical, symptom-based approaches suitable for non-specialist physicians?"

Search strategy

The literature search, which concluded on August 7, 2024, used databases, such as PubMed/MEDLINE and Cochrane Library, with keywords and Boolean operators as specified in table 1. PRISMA guidelines11 were followed, and EndNote managed citations.

Table 1 Keywords and Boolean operators used in the search strategy for electronic databases

| Arrhythmias OR Rhythm abnormalities OR Rhythm disturbances OR Rhythm alterations OR Electrical abnormalities OR electrical alterations OR Electrical disturbances OR Tachycardia OR Bradycardia OR Sinus arrhythmia OR Sinus bradycardia OR Wandering atrial pacemaker OR Atrial extrasystoles OR Premature atrial contractions OR Ventricular Extrasystoles OR Premature ventricular contractions OR Syncope OR Channelopathies OR Hereditary Arrhythmogenic Syndromes OR Long QT syndrome OR Brugada syndrome OR Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia OR Short QT syndrome OR Atrioventricular block OR AV block OR Ablation OR Pacing OR Pacemaker OR Cardioverter defibrillator OR Implantable Electronic Devices OR Inherited Arrhythmias AND (Pediatric OR Paediatric OR Young OR Children). |

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included diverse study designs-quantitative, qualitative, methodological, and theoretical-focused on pediatric arrhythmias7,8,12,13. Inclusion was restricted to studies published in English from 2019 to 2024, involving patients aged 2-18 years. Studies related to congenital heart disease (CHD) or other systemic conditions were excluded.

Selection of articles

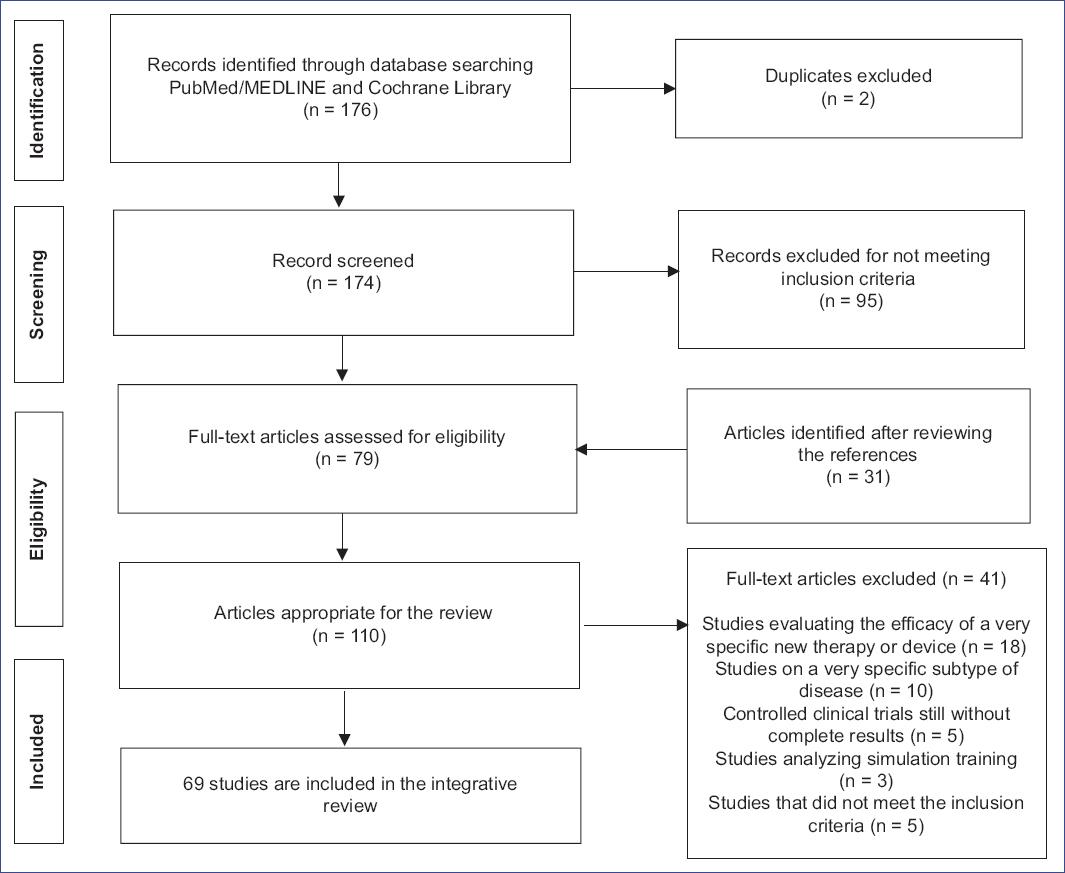

Two researchers independently assessed the eligibility of studies, screening titles, abstracts, and full texts, as documented in the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 2). Out of 176 studies, 79 were initially included, with 31 additional articles found through reference checks. After further screening, 41 studies were excluded, leaving 69 studies that met the criteria for this review.

Quality appraisal

Two independent reviewers assessed each study's methodological strengths and weaknesses using GRADE14 and CONSORT15 principles. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion. All studies were included post-evaluation, with 64 scoring high and five moderate. Table 2 shows all scores, while tables 3 and 4 provide examples of moderate and high-quality assessments.

Table 2 Data matrix for concept integration and thematic synthesis from comprehensive literature search

| Authors, year (ref) | Country | Design | Purpose/Aim | Quality appraisal data | Arrhythmias included | Symptoms | Strategies of diagnosis | Strategies of treatment | Strategies based on symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbasi et al., 202334 | Canada | Review | Review the management of acute SVT in children | High | SVT | T, L | ECG, clinical evaluation | Adenosine therapy, electrical therapy | Y |

| Amedro et al., 202162 | France | Prospective multicenter controlled study | Study the health-related quality of life and physical activity in children with inherited cardiac arrhythmia or cardiomyopathy | High | IA, IC | A, L | ECG, physical activity assessment | Lifestyle modifications, medications | Y |

| Babayiğit et al., 202033 | Turkey | Review | Review the European Society of Cardiology guidelines on SVT | High | SVT | A, L | ECG | Ablation | Y |

| Bieganowska et al., 202116 | Poland | Cohort study | Evaluate the usefulness of long-term telemetric ECG monitoring in the diagnosis of tachycardia in children with palpitations | High | Tachycardia | T, L | Long-term telemetric ECG monitoring | Medication, ablation | Y |

| Cano-Hernández et al., 201880 | Mexico | Cohort study | Analyze prevalence and diseases causing sudden cardiac death in children | High | SCD | L | Clinical evaluation | ICD | Y |

| Cepeda-Nieto et al., 202168 | Mexico | Case report | Identify polygenetic variants in Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome | High | Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome | L | Genetic testing | ICD | Y |

| Cheng et al., 202257 | China | Cohort study | Evaluate biomarkers and hemodynamic parameters in the diagnosis and treatment of POTS and vasovagal syncope in children | High | POTS, vasovagal syncope | T, S | Tilt test, biomarkers | Lifestyle modifications, medications | Y |

| Chhabra et al., 202338 | USA | Review | Overview of WPW syndrome | High | WPW syndrome | T | ECG | Ablation | Y |

| Chugh et al., 200982 | USA | Population-based study | Study sudden death in children | High | SCD | L | Clinical evaluation | ICD | Y |

| Cioffi et al., 202141 | USA | Review | Review the etiology and device therapy in pediatric and young adult population with complete AV block | High | Complete AV block | A, L, B | ECG, Holter monitoring | Pacemaker implantation | Y |

| Coban-Akdemir et al., 202042 | USA | Genetic study | Study genetic variants in WPW syndrome | High | WPW syndrome | T | Genetic testing | Ablation | Y |

| Cohen and Thurber, 20221 | USA | Review | Review the history of cardiac pacing in young patients and future directions | High | Cardiac pacing-related arrhythmias | A, L, T, B | ECG, device interrogation | Pacemaker implantation, programming | Y |

| Corcia MCG, 202275 | UK | Review | Review strategies to minimize overdiagnosis and overtreatment of Brugada syndrome in children | High | BrS | A, L | ECG, genetic testing | Lifestyle modifications, medications | Y |

| Cruz-Cardentey et al., 200982 | Cuba | Review | Overview of short QT syndrome | High | SQTS | L | ECG | ICD | Y |

| Cui et al., 202349 | China | Cohort study | Evaluate baroreflex sensitivity and its implication in neurally mediated syncope in children | High | Vasovagal syncope | S | Tilt test, clinical evaluation | Lifestyle modifications, medications | Y |

| Danon S, 20232 | USA | Review | Review the prevention of sudden cardiac death in children with chest pain, palpitations, and syncope | High | SCD | A, L | ECG, clinical evaluation | Lifestyle modifications, medications | Y |

| Dewi and Dharmadjati, 202078 | Indonesia | Review | Review diagnosis and management of short QT syndrome | High | SQTS | A | ECG | ICD | Y |

| Ebrahim et al., 202473 | USA | Review | Evaluate bidirectional ventricular tachycardia in pediatric and familial genetic arrhythmia syndromes | High | IA | A, L, T | Genetic testing, ECG | Beta-blockers, ICDs | Y |

| El-Battrawy et al., 202076 | Germany | Cohort study | Evaluate the clinical profile and long-term follow-up of children with Brugada syndrome | High | BrS | A, L | ECG, genetic testing | Beta-blockers, ICDs | Y |

| Endres et al., 202231 | USA | Multicenter retrospective study | Evaluate specialized laboratory investigations in pediatric patients with new-onset SVT | High | SVT | T, L | ECG, specialized labs | Medication, electrical therapy | Y |

| Groffen et al., 202467 | Netherlands | Review | Overview of long QT syndrome | High | LQTS | A, L | ECG, genetic testing | Beta-blockers, ICDs | Y |

| Hill et al., 201939 | USA | Randomized controlled trial | Compare the effectiveness of oral flecainide versus amiodarone for treating recurrent supraventricular tachycardia in children | High | SVT | T, L | ECG, clinical evaluation | Oral flecainide, amiodarone | Y |

| Howard and Vinocur, 202379 | USA | Review | Translate tools and techniques from adult electrophysiology to pediatric CIEDs | High | CIED-related arrhythmias | A, L, T | ECG, device interrogation | CIED implantation, programming | Y |

| Hu et al., 20213 | China | Cohort study | Investigate the incidence of syncope in children and adolescents aged 2-18 years in Changsha | High | Syncope | S | ECG, clinical evaluation | Lifestyle modifications, medications | Y |

| Ilkjaer et al., 202122 | Denmark | Retrospective clinical study | Evaluate the effectiveness and safety of radiofrequency catheter ablation in children with supraventricular tachyarrhythmia | High | SVT | T, L | ECG, electrophysiology study | Radiofrequency catheter ablation | Y |

| Janson et al., 202323 | USA | Registry study | Analyze the association of weight with ablation outcomes in pediatric WPW | High | WPW syndrome | T, L | ECG, electrophysiology study | Catheter ablation | Y |

| Kafalı and Ergül, 202230 | Turkey | Review | Review common SVT and VT in children | High | SVT, VT | T, L | ECG, clinical evaluation | Ablation, medications | Y |

| Kallas et al., 202128 | Canada | Multicenter cohort study | Evaluate age at symptom onset, proband status, and sex as predictors of disease severity in pediatric CPVT | High | CPVT | T, L | Genetic testing, ECG | Beta-blockers, ICDs | Y |

| Kallas et al., 202129 | Canada | Review | Provide a translational perspective on pediatric catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia for the clinician-scientist | High | CPVT | T, L | Genetic testing, ECG | Beta-blockers, ICDs | Y |

| Kim et al., 202036 | Korea | Cohort study | Evaluate the association between delayed adenosine therapy and refractory supraventricular tachycardia in children | High | SVT | T, L | ECG, clinical evaluation | Adenosine therapy | Y |

| Knight et al., 202065 | USA | Genetic study | Evaluate genetic testing and cascade screening in pediatric long QT syndrome and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | High | LQTS, HCM | A, L | Genetic testing, ECG | Beta-blockers, ICDs | Y |

| Kotadia et al., 202037 | UK | Review | Overview of SVT diagnosis and management | High | SVT | T, L | ECG, clinical evaluation | Ablation, medications | Y |

| Krahn et al., 202277 | Canada | Review | Review Brugada syndrome | High | BrS | L | ECG, genetic testing | ICD, medications | Y |

| Krause et al., 202143 | Germany | Multicenter registry study | Evaluate the outcomes of pediatric catheter ablation at the beginning of the 21st century | High | Various arrhythmias | T, L | Electrophysiology study | Catheter ablation | Y |

| Lee et al., 202163 | UK | Cohort study | Compare pediatric/young versus adult patients with long QT syndrome | High | LQTS | A, L | Genetic testing, ECG | Beta-blockers, ICDs | Y |

| Li et al., 202156 | China | Review | Review advancements in understanding vasovagal syncope in children and adolescents | High | Vasovagal syncope | S | Tilt test, clinical evaluation | Lifestyle modifications, medications | Y |

| Li et al., 201953 | China | Retrospective clinical study | Assess the efficacy of oral rehydration salts in children with neurally mediated syncope of different hemodynamic patterns | High | Vasovagal syncope | S | ECG, clinical evaluation | Oral rehydration salts | Y |

| Liao and Du, 202054 | China | Review | Update on the pathophysiology and individualized management of vasovagal syncope and postural tachycardia syndrome in children and adolescents | High | Vasovagal syncope, POTS | S | Tilt test, clinical evaluation | Lifestyle modifications, medications | Y |

| Mallya and Whitehouse, 202155 | UK | Retrospective clinical study | Audit the use of slow sodium in children and young people with syncope and/or orthostatic intolerance | High | Syncope, orthostatic intolerance | S | ECG, clinical evaluation | Lifestyle modifications, medications | Y |

| Mariani et al., 20244 | Italy | Review | Provide an updated overview of inherited arrhythmias in the pediatric population | High | IA | A, L, T | Genetic testing, ECG | Beta-blockers, ICDs | Y |

| Meyer et al., 201283 | USA | Review | Review incidence, causes, and trends in survival from sudden cardiac arrest in young population | High | SCA | L | Clinical evaluation, genetic testing | ICD, medications | Y |

| Moltedo et al., 202020 | Argentina | Retrospective clinical study | Study on HAV pattern in pediatric AVNRT | High | AVNRT | T | ECG, electrophysiology study | Ablation | Y |

| Oliveira et al., 202358 | Brasil | Cohort study | Examine clinical and autonomic profiles and validate the Modified Calgary Score in children with presumed vasovagal syncope | High | Vasovagal syncope | S | Tilt test, Modified Calgary Score | Lifestyle modifications, medications | Y |

| Oner et al., 201884 | Turkey | Prospective clinical study | Evaluate the effect of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation on cardiac function in children with premature ventricular contractions | High | PVCs | A, T | ECG, clinical evaluation | Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation | Y |

| Osama and Delpire, 202459 | USA | Review | Review insights into channelopathies | High | IA | A, L | Genetic testing, ECG | Medications, ICDs | Y |

| Patsiou et al., 202317 | Greece | Systematic review and meta-analysis | Compare epicardial versus endocardial pacing in pediatric patients with AV block or sinus node dysfunction | High | AV block, SND | L | ECG, Holter monitoring | Epicardial and endocardial pacing | Y |

| Peltenburg et al., 202272 | Netherlands | Multicenter cohort study | Evaluate the efficacy of β-blockers in treating children with CPVT | High | CPVT | T, L | ECG, genetic testing | Beta-blockers | Y |

| Ploneda-Valencia et al., 202218 | Mexico | Case report | Report a case of short QT syndrome presenting with supraventricular tachyarrhythmia and sinus node dysfunction | Moderate | SQTS | A, T | ECG, genetic testing | Beta-blockers, ICDs | Y |

| Przybylski et al., 202135 | USA | Review | Review the care of children with supraventricular tachycardia in the emergency department | High | SVT | T, L | ECG, clinical evaluation | Medication, electrical therapy | Y |

| Ramoğlu et al., 202240 | Turkey | Retrospective clinical study | Single-center experience with WPW syndrome in children | High | WPW syndrome | T | ECG, clinical evaluation | Ablation, medications | Y |

| Rohit and Kasinadhuni, 20205 | India | Review | Review the management of pediatric arrhythmias in emergency settings | High | Various arrhythmias | A, L, T | ECG, clinical evaluation | Medication, electrical therapy | Y |

| Romanov et al., 201924 | Russia | Randomized study | Compare catheter ablation versus medical therapy for treating symptomatic frequent ventricular premature complexes in children | High | PVCs | T, L | ECG, clinical evaluation | Catheter ablation, medication | Y |

| Sabaté Rotés et al., 202032 | Spain | Cohort study | Examine supraventricular tachycardia in children managed by a specialized transport team | Moderate | SVT | T, L | ECG, Holter monitoring | Medication, ablation | Y |

| Shimamoto and Aiba, 202470 | Japan | Review | Discuss strategies to evaluate arrhythmic risk in children with long QT syndrome | High | LQTS | A, L | Genetic testing, ECG | Beta-blockers, ICDs | Y |

| Shkolnikova et al., 201969 | Russia | Prospective clinical study | Evaluate new perspectives of holter monitoring in diagnostics of the long QT syndrome in the young | High | LQTS | A, L | Holter monitoring | Holter monitoring | Y |

| Silka et al., 202119 | USA | Expert consensus | Provide expert consensus on the indications and management of cardiovascular implantable electronic devices in pediatric patients | High | Various arrhythmias | A, L, T, B | ECG, clinical evaluation | Implantable devices, follow-up | Y |

| Siurana et al., 202047 | Spain | Case report | Report a case of asystole triggered by hair grooming in children and review related literature | Moderate | Asystole | L | ECG, clinical history | Avoiding triggers, pacemaker | Y |

| Sohinki and Mathew, 201885 | USA | Review | Review ventricular arrhythmias in structurally normal heart | High | VA | A, L | ECG, clinical evaluation | Medications | Y |

| Song et al., 202048 | China | Pilot study | Evaluate the association between reduced 24-h sodium excretion and plasma acylcarnitine profile in vasovagal syncope children | High | Vasovagal syncope | S | ECG, clinical evaluation | Sodium intake modifications | Y |

| Song et al., 202174 | Korea | Multicenter cohort study | Evaluate outcomes of ICDs in pediatric patients in a Korean cohort | High | Various arrhythmias | T, L | ICD implantation, follow-up | ICDs | Y |

| Steinberg L, 202344 | USA | Review | Overview of congenital heart block | High | Congenital heart block | L, B | ECG, clinical evaluation | Pacemaker | Y |

| Stewart et al., 202346 | Netherlands | Review | Develop a framework for diagnosing pediatric syncope | High | Syncope | A, L | Clinical evaluation, diagnostic framework | Tailored management strategies | Y |

| Tardo et al., 202366 | Australia | Systematic review | Systematic review on T wave biomarkers in long QT syndrome | High | LQTS | A, L | ECG, genetic testing | Beta-blockers, ICDs | Y |

| Uysal et al., 202421 | Turkey | Prospective clinical study | Evaluate the effect of magnesium on ventricular extrasystoles in children | High | PVCs | A, T | ECG, clinical evaluation | Magnesium supplementation | Y |

| Vidya et al., 202225 | India | Randomized clinical study | Evaluate the use of implantable loop recorder in unexplained palpitations or syncope in young patients with structurally normal heart | High | Unexplained palpitations, syncope | P, S | Implantable loop recorder | Implantable loop recorder | Y |

| Vogler et al., 201286 | Germany | Review | Review bradyarrhythmias and conduction blocks | High | Bradyarrhythmia | A, L | ECG, clinical evaluation | Pacemaker | Y |

| Wallace et al., 201964 | Ireland | Review | Review genetics and future perspectives of long QT syndrome | High | LQTS | A, L | ECG, genetic testing | Beta-blockers, ICDs | Y |

| Walsh et al., 202126 | UK | Systematic review | Review outcomes of pediatric ablation over 20 years | High | Various arrhythmias | T, L | Electrophysiology study | Catheter ablation | Y |

| Wang et al., 202050 | China | Cohort study | Investigate the association between neurally mediated syncope and allergic diseases in children | Moderate | Vasovagal syncope | S | Clinical evaluation, allergy tests | Management of allergies, lifestyle modifications | Y |

| Weiner and Shah, 202345 | USA | Case series | Review of nonsurgical complete AV block in children and its management | High | Complete AV block | L, B | ECG, Holter monitoring | Pacemaker implantation | Y |

| Wilde et al.; EHRA/HRS/APHRS/LAHRS; 202271 | Consensus Statement | Consensus statement on genetic testing for cardiac diseases | High | Various arrhythmias | A, L | Genetic testing, ECG | Medications, ICDs | Y | |

| Xinxing et al., 202052 | China | Cohort study | Evaluate the safety and efficacy of RF ablation in pediatric patients with arrhythmias | High | Various arrhythmias | T, L | Electrophysiology study | RF ablation | Y |

| Xu et al., 202251 | China | Observational study | Explore individual management strategies for pediatric vasovagal syncope | Moderate | Vasovagal syncope | S | Tilt table test, clinical evaluation | Lifestyle modifications, medications | Y |

| Yan et al., 202327 | China | Cohort study | Examine clinical and genetic characteristics of CPVT in Chinese pediatric patients | High | CPVT | T, L | Genetic testing, ECG | Beta-blockers, ICDs | Y |

| Zavala et al., 202060 | USA | Systematic review | Review of pediatric syncope, its causes, and management | High | Syncope | A, L | Clinical evaluation, tilt table test | Lifestyle modifications, medications | Y |

| Zou et al., 202461 | China | Systematic review | Investigate the association between PFO and unexplained syncope in pediatric patients | High | PFO, Syncope | S | Echocardiography, clinical evaluation | Medical management, follow-up | Y |

A: asymptomatic; APHRS: Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society; AV: atrioventricular; AVNRT: atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia; B: symptoms associated to bradycardia; BrS: Brugada syndrome; CIED: cardiac implantable electronic devices; CPVT: catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia; ECG: electrocardiogram; EHRA: European Heart Rhythm Association; HCM: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; HRS: Heart Rhythm Society; IA: inherited arrhythmias; IC: inherited cardiomyopathies; ICD: implantable cardioverter defibrillator; L: life threating symptoms including malignant syncope; LAHRS: Latin American Heart Rhythm Society; LQTS: long QT syndrome, N: no; PFO: patent foramen ovale; POTS: postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome; PVCs: premature ventricular contractions; S: benign syncope; SCA: sudden cardiac arrest; SCD: sudden cardiac death; SND: sinus node disfunction; SQTS: short QT syndrome; SVT: supraventricular tachycardia; T: paroxysmal tachycardia; VA: ventricular arrythmias; VT: ventricular tachycardia; WPW: Wolff-Parkinson-White; Y: yes.

Table 3 Example of the quality assessment of a study with a moderate quality rating

| Article evaluation Asystole in a syncope by hair grooming in children: case report and literature review | ||

|---|---|---|

| Criterion | Description | Evaluation |

| Study type | Determine the study design (clinical trial, cohort study, etc.). | Case report and literature review |

| Internal validity | Evaluate sample selection, allocation, and follow-up. | Sample Selection: case report based on specific clinical observation. |

| Allocation: not applicable. | ||

| Follow-up: detailed follow-up of the individual case. | ||

| External validity | Consider the generalizability of the results to other populations and settings. | Results are specific to a unique case and context, limiting generalizability. A literature review provides a broader context but remains limited in direct applicability. |

| Precision and consistency | Review measurement, statistical analysis, and consistency with previous studies. | Measurement: detailed clinical measurements were provided for the case. |

| Statistical analysis: not applicable in case reports. Consistency: supported by literature review, though direct comparisons are limited. | ||

| Results | Analyze the magnitude of the effect and its clinical relevance. | Impact: clinically relevant insights into a rare phenomenon. |

| Consistency: unique case but contextualized within the literature. | ||

| Transparency and ethics | Verify the completeness of reporting, ethical approval, and informed consent. | Complete reporting: methodology and case details are well reported. |

| Ethical approval: ethical considerations and informed consent obtained. | ||

| Conclusion | The article is assessed as having moderate quality. It excels in transparency, detailed reporting, and ethical considerations, which are crucial in case reports. However, its inherent limitations in generalizability and the absence of statistical analysis reduce its overall robustness. The literature review component adds valuable context but does not fully mitigate the limitations associated with the single-case study design. | |

Table 4 Example of the quality assessment of a study with a high-quality rating

| Article evaluation: Health-related quality of life and physical activity in children with inherited cardiac arrhythmia or inherited cardiomyopathy: The prospective multicenter controlled QUALIMYORYTHM study rationale design and methods | ||

|---|---|---|

| Criterion | Description | Evaluation |

| Study type | Determine the study design (clinical trial, cohort study, etc.). | Prospective multicenter controlled study |

| Internal validity | Evaluate sample selection, allocation, and follow-up. | Sample Selection: randomly selected samples from multiple centers. |

| Allocation: use of control and intervention groups with random allocation. | ||

| Follow-up: adequate follow-up with minimal loss of participants. | ||

| External validity | Consider the generalizability of the results to other populations and settings. | Results applicable to children with inherited cardiac arrhythmias or cardiomyopathy in similar contexts. |

| Precision and consistency | Review measurement, statistical analysis, and consistency with previous studies. | Measurement: use of validated tools to measure quality of life and physical activity. |

| Statistical analysis: adequate statistical methods with reported confidence intervals. | ||

| Results | Analyze the magnitude of the effect and its clinical relevance. | Impact: significant effect on quality of life and physical activity. |

| Consistency: results consistent with previous studies in the same area. | ||

| Transparency and ethics | Verify the completeness of reporting, ethical approval, and informed consent. | Complete reporting: detailed methodology and results. Ethical approval: Ethical approval obtained and informed consent given. |

| Conclusion | By following these steps, it can be determined that the article has a high-quality evaluation (High) based on its design, internal and external validity, precision, consistency, impact, and ethical compliance. | |

Data abstraction and synthesis

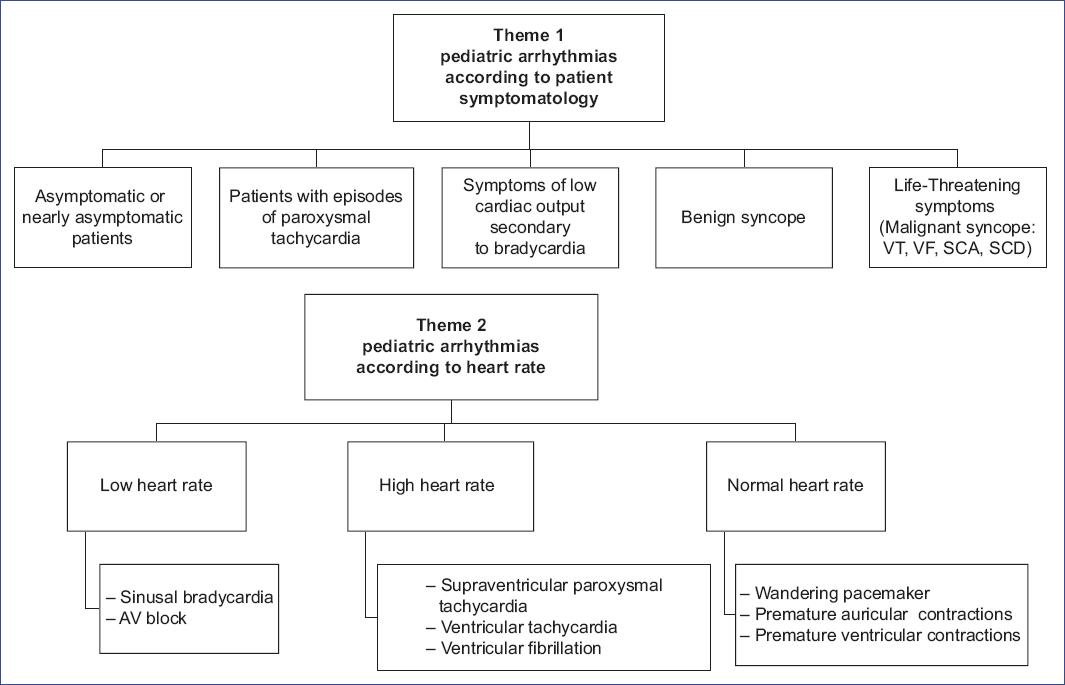

A data matrix (Table 2) was created to integrate concepts across the literature, streamlining data analysis and supporting narrative syntesis1-5,16-86. Inductive content analysis was conducted in three phases: preparation, organizing, and reporting. Qualitative analysis identified unifying themes, which are summarized in figure 3. The process involved identifying common meanings and refining categories through collaborative discussion, ultimately consolidating them into synthesized themes that form the foundation of the findings.

Results

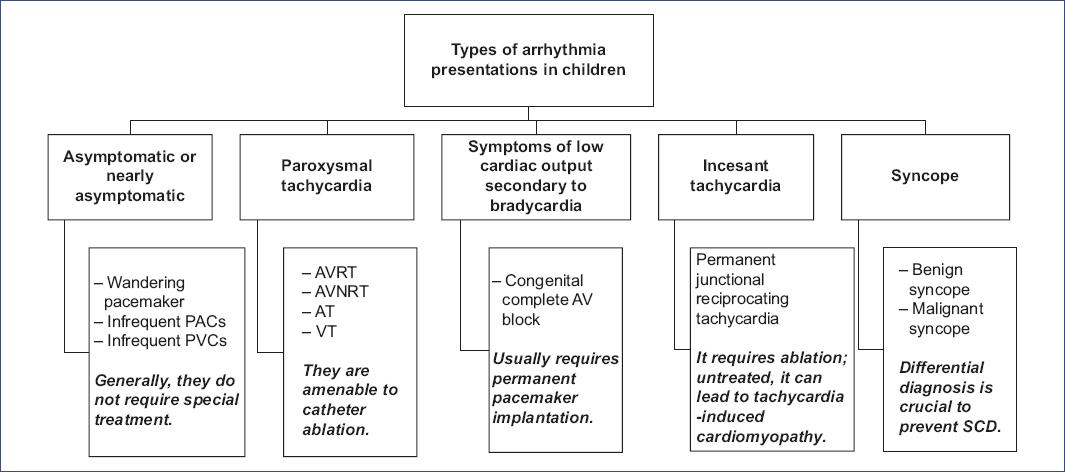

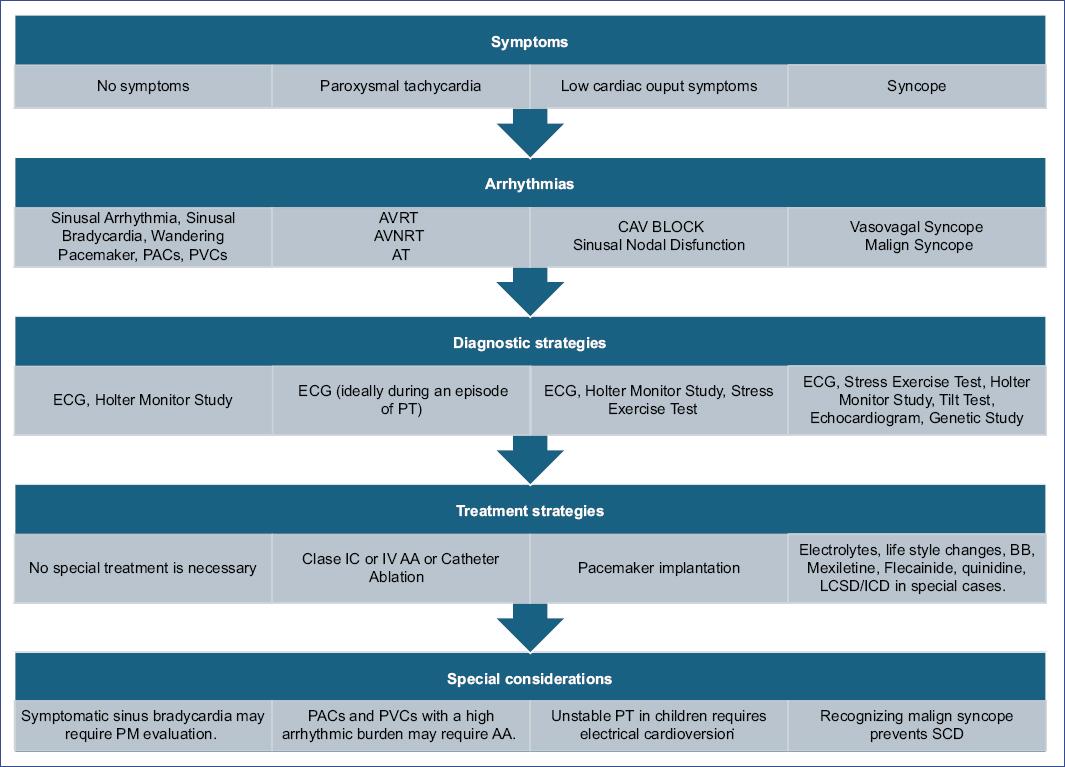

To ensure the comprehensive integration of the organized synthesis of evidence into practice, we developed an innovative symptom-based conceptual framework, designed to serve as a practical guide for the management of pediatric arrhythmias, as summarized in figures 4 and 5.

Figure 4 Classification of pediatric arrhythmia presentations. The figure categorizes types of arrhythmias in children based on symptom severity and clinical presentation, ranging from asymptomatic cases to those requiring intervention. It highlights the importance of differential diagnosis in syncope cases to prevent sudden cardiac death (SCD). AT: atrial tachycardia; AVNRT: atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia; AVRT: atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia; PACs: premature auricular contractions, PVCs: premature ventricular contractions; VT: ventricular tachycardia.

Figure 5 Symptom-based conceptual framework developed for the practical management of pediatric arrhythmias, integrating the organized synthesis of evidence into clinical practice. AA: antiarrhythmic agents; AT: atrial tachycardia; AVNRT: atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia; AVRT: atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia; BB: betablocker; CAV: complete atrioventricular; ECG: electrocardiogram; ICD: implantable cardioverter defibrillator; LCSD: left cardiac sympathetic denervation; PACs: premature atrial contractions; PM: pacemaker; PT: paroxysmal tachycardia; PVCs: premature ventricular contractions; SCD: sudden cardiac death.

Practical guide for the care of children with arrhythmias based on symptomatology

ASYMPTOMATIC OR NEARLY ASYMPTOMATIC CHILDREN

Common arrhythmias in asymptomatic children typically do not require treatment. However, some conditions, such as pre-excitation syndrome and long QT syndrome (LQTS)16, can be asymptomatic for some time but may still pose a risk and require special diagnostic attention and follow-up. The most common asymptomatic arrhythmias in children include sinus arrhythmia, sinus bradycardia, wandering pacemaker, and infrequent premature atrial and ventricular contractions.

Sinus arrhythmia

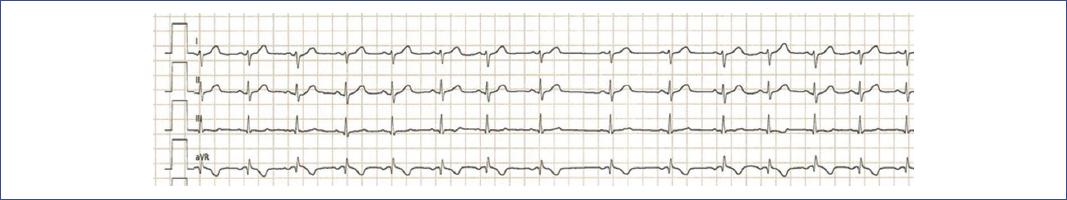

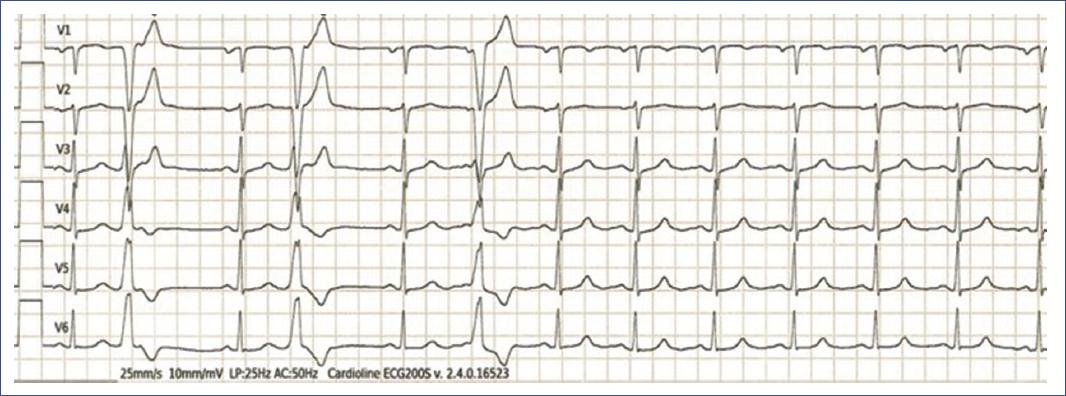

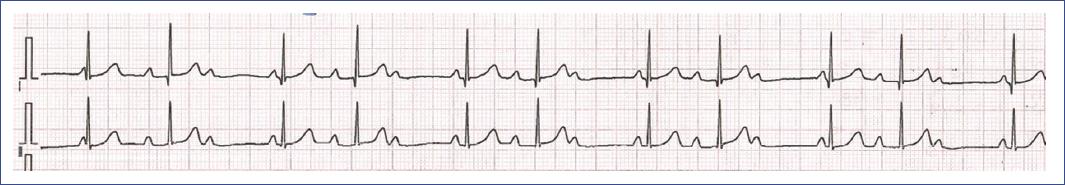

Prevalence and mechanism: sinus arrhythmia is a common electrocardiographic finding in children5, characterized by heart rate (HR) variations with respiration (increasing during inspiration and decreasing during exhalation) due to vagal influence (Fig. 6). This pattern may disappear with intense exercise as sympathetic activity increases.

Figure 6 4-lead electrocardiogram showing sinus arrhythmia in a pediatric patient. The tracing displays normal P wave morphology and a regular sinus rhythm with varying R-R intervals, characteristic of sinus arrhythmia.

Symptoms: asymptomatic.

Diagnostic strategies: diagnosed through electrocardiogram (ECG) or Holter monitoring.

Treatment strategies: no specific treatment required.

Special considerations: Non-respiratory sinus arrhythmia, potentially linked to mild sinus node dysfunction caused by increased vagal tone, may warrant long-term follow-up17,18.

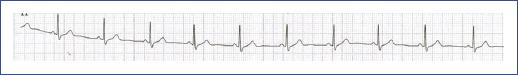

Sinus bradycardia

Prevalence and mechanism: significant sinus bradycardia (HR < 60 beats/min [bpm]) is common in healthy children, often due to parasympathetic dominance or long-term sports participation, both typically benign.

Symptoms: usually asymptomatic.

Diagnostic strategies: diagnosed through ECG; more pronounced during deep sleep, as shown by Holter monitoring (Fig. 6). Normal HR response in exercise tests indicates normal sinus function.

Treatment strategies: no treatment required for asymptomatic patients.

Special considerations: symptomatic bradycardia with chronic low cardiac output symptoms requires evaluation by an electrophysiology team to assess the need for a pacemaker19.

Wandering atrial pacemaker

Prevalence and mechanism: common in children, involving atrial foci generating impulses from lower atrial or perinodal regions.

Symptoms: asymptomatic.

Diagnostic strategies: ECG shows QRS complexes similar to sinus beats but with varying P wave morphologies. Holter monitoring may reveal competition between multiple pacemakers (Fig. 7).

Figure 7 24-h Holter monitoring ECG tracing in a 4-year-old girl showing sinus bradycardia followed by low atrial beats at a slower heart rate with a different P-wave morphology during deep sleep. The tracing highlights the transition from sinus rhythm to ectopic atrial rhythm, which is common during periods of increased vagal tone, such as in deep sleep.

Treatment strategies: no specific treatment required; the condition usually resolves as atrial foci disappear.

Special considerations: often observed as escape beats during increased vagal tone, such as in deep sleep. Although typically benign, monitoring HR variability and rhythm changes during sleep is advised.

Premature atrial contractions (PACs)

Prevalence and mechanism: PACs are common in newborns and young children, caused by pre-mature atrial depolarization leading to ventricular contraction5,20. They generally have an excellent prognosis.

Symptoms: asymptomatic.

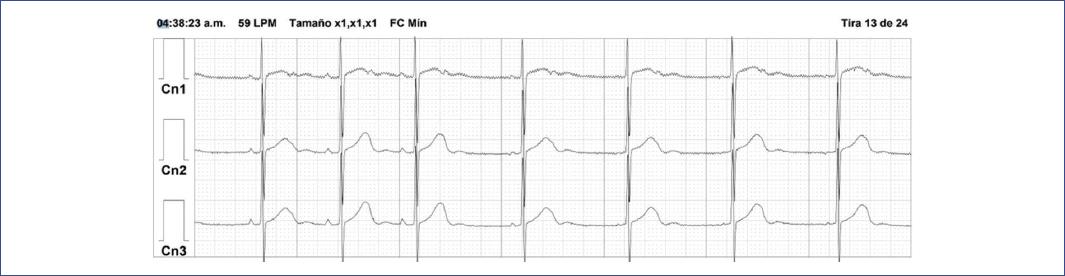

Diagnostic strategies: diagnosed through ECG or Holter monitoring, showing pre-mature beats with QRS complexes similar to sinus beats (Fig. 8).

Figure 8 Electrocardiogram trace from a Holter monitor study illustrates the presence of a premature atrial contraction in channels 1, 2, and 3, characterized by the early occurrence of a P wave (highlighted in yellow) with a distinct morphology, followed by a QRS complex similar to that of a sinus beat and a compensatory pause. The normal sinus rhythm is interrupted by this ectopic beat originating from the atria, which resets the timing of subsequent cardiac cycles.

Treatment strategies: no special treatment required.

Special considerations: In rare cases with high arrhythmic burden or symptoms, antiarrhythmic treatment may be necessary.

Premature ventricular contractions (PVCs)

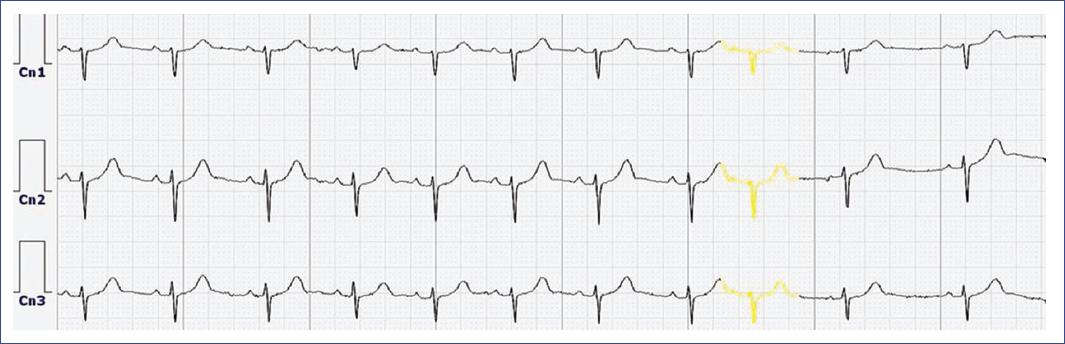

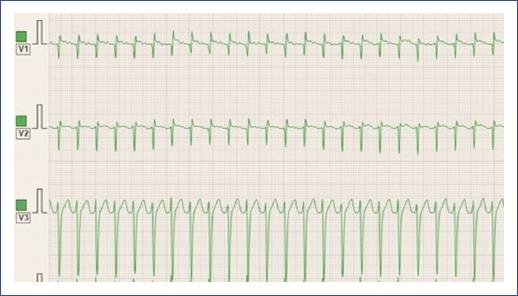

Prevalence and mechanism: PVCs arise from pre-mature ventricular depolarization, leading to a systolic contraction and compensatory pause. They are less frequent in childhood but increase during adolescence21, often occurring in bigeminy (Fig. 9) or trigeminy patterns.

Figure 9 6-lead Electrocardiogram showing pre-mature, broad QRS complexes not preceded by P waves, with morphology different from the sinus beats, characteristic of ventricular ectopic beats. These pre-mature ventricular contractions interrupt the regular sinus rhythm in a pattern consistent with bigeminy.

Symptoms: usually asymptomatic or cause mild symptoms, such as palpitations.

Diagnostic Strategies: diagnosed through ECG or Holter monitoring, showing wide QRS complexes with repolarization abnormalities (Fig. 9).

Treatment strategies: infrequent, asymptomatic PVCs typically require no treatment. Frequent PVCs (over 10% of total beats in 24 h) may need antiarrhythmic drugs or catheter ablation22-26.

Special considerations: frequent or polymorphic PVCs, or a family history of sudden death, warrant close attention due to the risk of malignant arrhythmias, such as catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) or arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy (ARVD/C)27-29.

CHILDREN WITH EPISODES OF PAROXYSMAL TACHYCARDIA

Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT)

Prevalence and Mechanism: SVT is the most common pediatric arrhythmia, affecting 0.1%-0.4% of children, primarily due to re-entry mechanisms. Around 50%-70% of cases are diagnosed within the 1st year, with 30%-50% resolving by 18 months30-32. Later childhood SVT has a lower chance of spontaneous resolution18,30,33,34.

Symptoms: young children may show crying and irritability, while older children report palpitations.

Diagnostic strategies: diagnosis involves a 12-lead ECG and assessing hemodynamic status. HR ranges from 200-300 bpm in younger children and 160-250 bpm in older ones. Basal ECG is usually normal unless ventricular pre-excitation is present35.

Treatment strategies: hemodynamically stable cases are first treated with vagal maneuvers; if ineffective, intravenous adenosine is used. Adenosine blocks the AV node and helps diagnose other SVT types23,36-38. If adenosine fails, esmolol, amiodarone, or verapamil (not for children under 1 year)39 may be used. Hemodynamically unstable cases require synchronized electrical cardioversion at 1-2 J/kg.

Special considerations: the main re-entry tachycardias in children are atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia (AVRT), including Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome, and atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia (AVNRT)20,33,40,41.

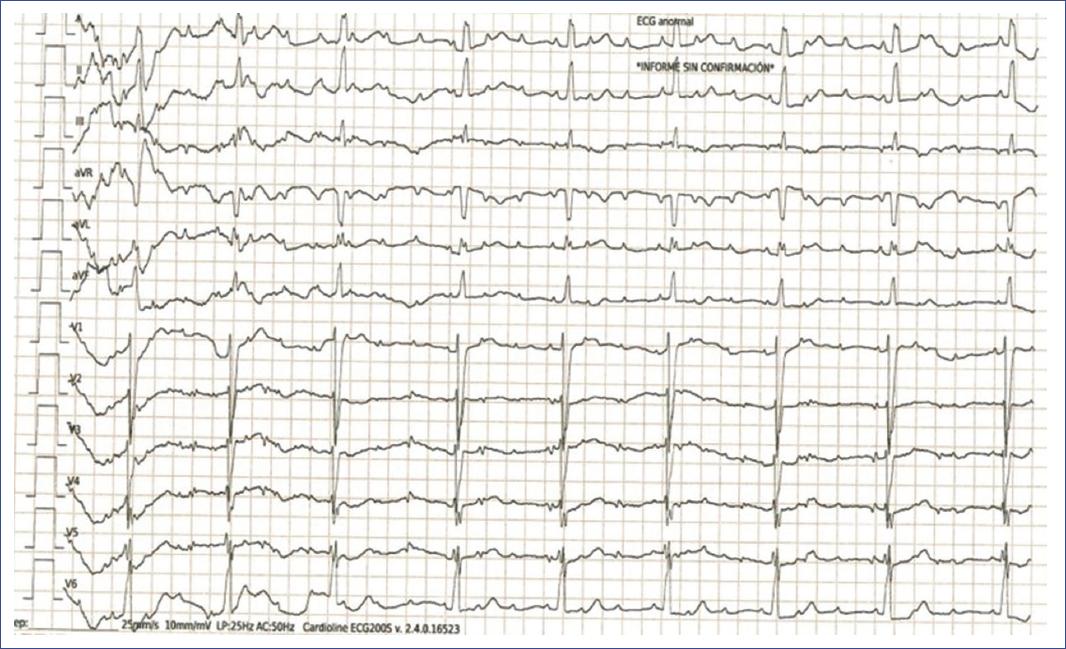

a) AVRT. AVRT using accessory pathways (APs) is the most common subtype of SVT in children, with the left lateral AV groove and postero-septal region being the most common sites. The prevalence is estimated at 1-3/1,000 children20. In cases with manifest AP, the QRS complex shows a sloping delta wave, short PR interval, and wide QRS complex, known as the WPW pattern (Fig. 10)38,40. WPW syndrome includes this pattern along with symptoms such as palpitations and SVT, and less commonly, syncope or sudden cardiac arrest. Treatment ranges from only vagal maneuvers to transcatheter ablation. Familial WPW syndrome, associated with mutations in the PRKAG2 gene and conditions, such as cardiomyopathy, has been reported38. Rare variants in genes linked to atrial fibrillation (AF) and cardiomyopathy have also been identified in WPW syndrome42.

Figure 10 Electrocardiogram demonstrating Wolff-Parkinson-White pattern with characteristic findings, including a short PR interval, delta wave, wide QRS complex, and repolarization abnormalities indicative of pre-excitation due to an accessory pathway.

Variants of AVRT41:

− Orthodromic AVRT: the most common AVRT mechanism, with antegrade conduction through the AV node and retrograde conduction up the AP, resulting in narrow QRS complex tachycardia (Fig. 11).

− Antidromic AVRT: an uncommon form (< 5% of cases) where impulses travel antegrade down an AP and retrograde up the AV node, leading to wide QRS complex tachycardia (Fig. 12).

− Permanent Junctional Reciprocating Tachycardia (PJRT): a variant of orthodromic AVRT with slow retrograde AP conduction, creating a stable, often incessant reentrant circuit.

b) Atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia. AVNRT involves a re-entering loop within or near the AV node, utilizing fast and slow pathways with distinct conduction rates. In typical AVNRT, antegrade conduction is through the slow pathway and retrograde through the fast pathway, leading to a very short RP interval tachycardia (< 70 ms)20,30. Catheter ablation is the preferred treatment for recurrent cases20,26,30,43.

c) Atrial Tachycardia (AT). AT is an organized atrial rhythm from a discrete site, accounting for 11%-16% of SVTs in children and often leading to incessant tachycardias and tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy. It presents as a long RP tachycardia on ECG with a distinct P-wave morphology (Fig. 13). Conservative treatment with antiarrhythmic drugs is recommended, as AT often resolves over time in young children30.

Figure 11 12-lead electrocardiogram demonstrating orthodromic AVRT in a child with a high heart rate. The ECG shows a narrow complex tachycardia with a rapid ventricular rate, consistent with AVRT. The P waves are typically retrograde and may not be clearly visible, as they are often buried within or immediately following the QRS complexes, reflecting conduction through an accessory pathway. AVRT: atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia.

Figure 12 3-lead electrocardiogram shows a regular, rapid tachycardia with broad QRS complexes, indicating that the reentrant circuit is utilizing an accessory pathway in the antegrade direction (antidromic), leading to a wider QRS morphology compared to orthodromic AVRT. This type of tachycardia is less common but can occur in pediatric patients with pre-excitation syndromes, such as Wolff-Parkinson-White. AVRT: atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia.

Figure 13 3-lead ECG demonstrating atrial tachycardia in a young child. The ECG shows a rapid, regular atrial rhythm with narrow QRS complexes and distinct P waves preceding each QRS complex. The P waves exhibit an abnormal morphology, suggesting a focal atrial origin rather than the sinus node. ECG: electrocardiogram.

Ventricular tachycardia

Prevalence and mechanism: VT originates in the ventricular myocardium and is less common than SVT, with an incidence of 1/100,000 in children31. It can be benign (idiopathic) or malignant (risk of SCD). Idiopathic VT, especially from the right ventricular outflow tract, is common in children, triggered by beta-adrenergic stimuli like exercise30,33,35.

Symptoms: similar to SVT, young children may show irritability, while older children report abnormal heartbeats.

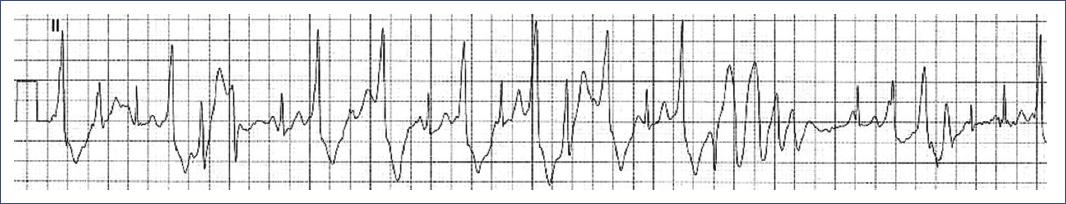

Diagnostic strategies: defined by three or more PVCs with a rate 20%-25% faster than the basal sinus rate, characterized by wide QRS complexes observed on an ECG, Holter monitor study (Fig. 14), or stress exercise test.

Figure 14 Holter monitor study demonstrating ventricular tachycardia in an adolescent. The electrocardiogram shows a rapid, wide-complex tachycardia with a monomorphic appearance, indicative of ventricular tachycardia. The absence of preceding P waves and the broad QRS complexes are characteristic of VT, suggesting that the origin of the arrhythmia is within the ventricles.

Treatment strategies: idiopathic VT responds to IV verapamil and may be terminated with IV adenosine. Transcatheter ablation is also effective30,43.

Special considerations: idiopathic left ventricular posterior fascicular VT, involving the left posterior fascicle and partially using the His-Purkinje system, results in a relatively narrow QRS complex.

CHILDREN WITH SYMPTOMS OF LOW CARDIAC OUTPUT SECONDARY TO BRADYCARDIA

Congenital atrioventricular block

Prevalence and mechanism: congenital AV block, often caused by maternal lupus (60-90%), results from anti-RO-SSA and anti-LA-SSB antibodies crossing to the baby during pregnancy. Other causes include myocarditis and CHD17,30,44.

Symptoms: common symptoms include fatigue, reduced physical capacity, drowsiness, loss of appetite, abdominal pain, and failure to thrive. In newborns, it may present as heart failure (HF)44.

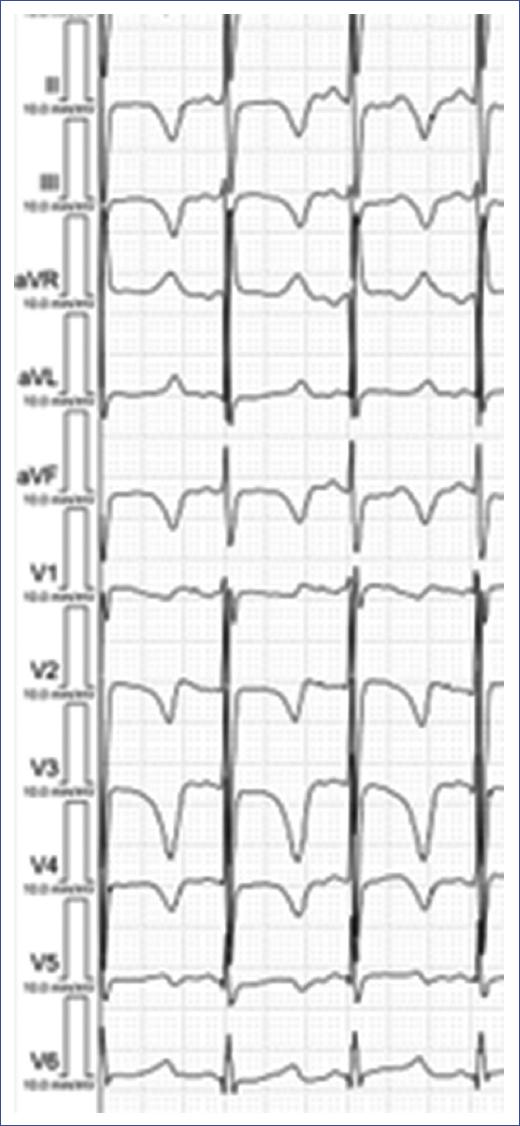

Diagnostic strategies:

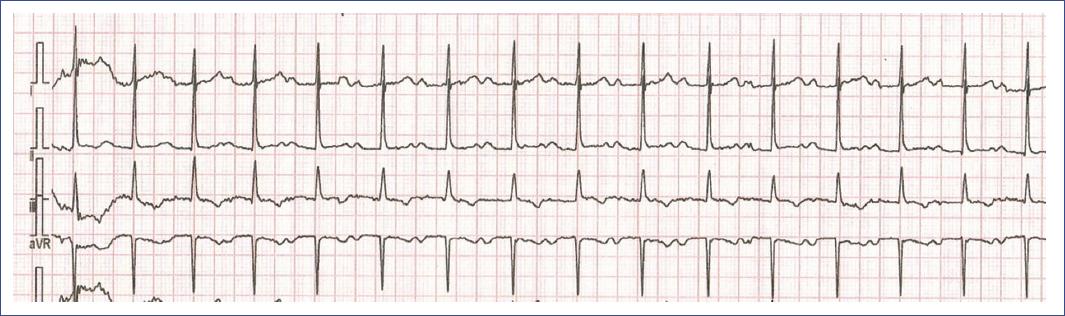

- First-degree AV block. Characterized by a prolonged PR interval on ECG (Fig. 15), usually asymptomatic and benign, with treatment focused on the underlying cause30,44.

- Second-degree AV block. Occurs when the atrial impulse fails to reach the ventricle correctly and is further divided into two categories:

Mobitz type I (with Wenckebach phenomenon): progressive PR prolongation until a P wave fails to conduct, often asymptomatic and benign30,44.

Mobitz type II: unchanged PR interval with the sudden failure of P wave conduction (Fig. 16), indicating more severe disease and risk of complete block30,44.

Treatment strategies: symptomatic patients may require permanent pacemaker implantation to improve quality of life and prevent bradycardiomyopathy.

Figure 15 3-lead ECG demonstrating first-degree AV block in a 13-year-old girl. The ECG shows a prolonged PR interval > 200 ms, consistent with first-degree AV block. Despite the delay in atrioventricular conduction, every P wave is followed by a QRS complex, indicating that conduction through the AV node is intact. This condition is generally benign, especially in young patients, but monitoring may be required if there are symptoms or if the condition progresses. AV: atrioventricular; ECG: electrocardiogram.

Figure 16 Holter monitor study demonstrating second-degree atrioventricular (AV) block. The ECG shows intermittent failure of conduction from the atria to the ventricles, as evidenced by the dropped QRS complex after some P waves, indicative of second-degree AV block. In this trace, a P wave is not followed by a QRS complex, suggesting a Mobitz type II AV block, where the PR intervals remain constant before the block. This type of AV block can be more serious and may require further evaluation and management. AV: atrioventricular; ECG: electrocardiogram

Figure 17 ECG of a 4-year-old girl with congenital high-grade atrioventricular (AV) block, recorded before pacemaker implantation. The ECG shows a high-grade AV block with intermittent conduction. Some P waves are followed by QRS complexes, indicating that occasional atrial impulses are successfully conducted to the ventricles. However, many P waves do not result in QRS complexes, reflecting the impaired conduction through the AV node. The ventricular rate is slow due to this intermittent conduction, and the QRS complexes are narrow, suggesting they originate from above the His bundle when conduction occurs. This degree of conduction abnormality prompted the decision to implant a pacemaker to prevent symptomatic bradycardia and ensure stable cardiac output. AV: atrioventricular; ECG: electrocardiogram.

Figure 18 ECG of a 2-year-old boy with congenital complete AV block. The ECG demonstrates a complete dissociation between atrial and ventricular activities, characteristic of third-degree AV block. The P waves occur regularly but have no consistent relationship with the QRS complexes, which also appear at a regular but much slower rate. The QRS complexes are narrow, indicating a junctional escape rhythm as the ventricles independently generate their own rhythm due to the absence of atrial conduction. This severe conduction abnormality often requires early intervention, such as pacemaker implantation, to manage the risk of significant bradycardia and its associated symptoms in a small child. AV: atrioventricular; ECG: electrocardiogram

Special considerations: patients with complete AV block and CHD are at increased risk of HF and SCD45. Acquired complete AV block can result from myocarditis, Lyme disease, rheumatic disease, trauma, or cardiomyopathy45.

CHILDREN WITH SYNCOPE

Syncope, a sudden loss of consciousness due to insufficient cerebral perfusion, is common in children, with a 40% lifetime prevalence and accounting for 1% of emergency department admissions2,3. The causes of syncope vary widely and require a systematic approach to identify high-risk patients and manage them appropriately46-55. While some arrhythmias, such as bradycardia from complete AV block or tachycardia in WPW syndrome, can cause syncope, the primary concerns are benign vasovagal or situational syncope and malignant syncope from ventricular fibrillation (VF) due to genetic channelopathies54,56,57. Prompt recognition and treatment are critical to prevent SCD.

Benign vasovagal and situational syncope

Classified as benign based on specific criteria (Table 5), it is common and typically managed with lifestyle adjustments such as increased electrolyte intake and avoidance of triggers56,57. Tilt-table testing may help diagnose and refine treatment strategies58.

Table 5 Common clinical criteria to differentiate benign from malignant syncope in children

| Benign syncope in children | |

|---|---|

| There is no family history of channelopathy or sudden death. | √ |

| Normal 12-lead ECG (without Brugada pattern and a normal corrected QT interval). | √ |

| Normal physical examination (no murmurs or other abnormalities in heart sounds). | √ |

| Syncope duration and recovery are rapid. | √ |

| Syncope did not occur during physical exertion or stress. | √ |

| A typical trigger for benign syncope can be identified, such as prolonged standing, abdominal pain, urination, defecation, hair brushing, exposure to intense smells (e.g., chemicals or medications), or seeing blood, syringes, or needles during blood draws or vaccine administration, extreme heat. | √ |

| It is very important to rule out inherited arrhythmias: LQTS, BrS, CPVT, and SQTS. | √ |

| Malignant syncope in children | |

| There is a family history of channelopathy and/or sudden death. | √ |

| The 12-lead ECG is abnormal* (QTc prolongation, Brugada pattern, Conduction abnormalities, Increased QRS complex voltages, abnormalities in repolarization, etc.). | √ |

| Physical examination may be normal. | √ |

| Syncope duration and recovery are slower than in benign syncope. | √ |

| Syncope occurs during physical exertion or stress, or while swimming or after an intense noise. | √ |

| Commonly associated triggers for vasovagal syncope are generally absent. | √ |

| Malignant syncope in children is caused by inherited arrhythmias: LQTS, BrS, CPVT, SQTS. | √ |

*Except for catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia that usually presents a normal resting ECG. CPVT: catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia; LQTS: long QT syndrome; BrS: Brugada syndrome; SQTS: short QT syndrome.

Malignant syncope

Requires careful analysis to identify cases secondary to diseases that cause SCD, primarily inherited arrhythmias (IAs) that alter ion channel function and predispose to VT and VF (Table 5)59-61.

The importance of genetic factors in pediatric arrhythmias

Genetic factors play a crucial role in pediatric arrhythmias, particularly in IAs, such as LQTS, Brugada syndrome (BrS), and CPVT. These channelopathies, characterized by ion channel dysfunction despite normal heart structure, carry high mortality risks in children59. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has improved the detection of pathogenic mutations in over 200 genes, increasing the identification of disease-causing mutations, though many variants remain classified as uncertain significance (VUSs)62. Channelopathies contribute to approximately 10% of SCD cases, with an incidence of 0.5-20/100,000 person-years from birth to age 35.

a) Congenital LQTS

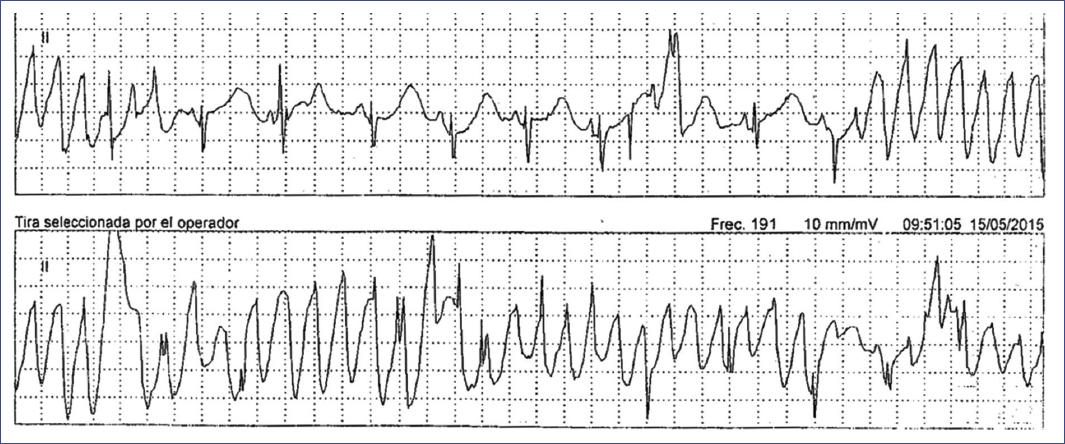

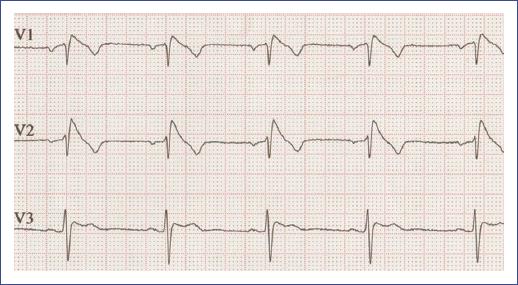

Prevalence and Mechanism: LQTS is a heritable condition characterized by a prolonged QT interval, abnormal T waves (Fig. 19), recurrent syncope, and SCD. It affects 1 in 2,000 individuals, with an annual SCD rate of 0.5%, increasing to 5% in those with a history of syncope63. LQTS is linked to mutations in 17 genes, primarily involving potassium and sodium channels, leading to prolonged action potentials and risk of torsades de pointes (Fig. 20) and SCD.

Figure 19 ECG of a young child with LQTS. The ECG displays a markedly prolonged QT interval (measured at 526 ms), evident in all leads, which is characteristic of Long QT Syndrome. The T waves are broad and abnormally shaped, with some leads showing notched or biphasic T waves. This prolonged repolarization increases the risk of life-threatening arrhythmias, such as torsades de pointes, in affected individuals. Early diagnosis and appropriate management, including lifestyle modifications and possibly medication, are crucial to reduce the risk of sudden cardiac events in children with LQTS. LQTS: long QT syndrome.

Figure 20 24-h Holter monitoring ECG tracing in a child diagnosed with LQTS. The tracing reveals episodes of torsades de pointes, a polymorphic ventricular tachycardia characteristic of LQTS, with fluctuating QRS axis and amplitude. These arrhythmic episodes are preceded by a prolonged QT interval, which is the hallmark of the syndrome. The presence of these life-threatening arrhythmias underscores the high risk associated with LQTS in children, necessitating immediate medical intervention. LQTS: long QT syndrome.

Loss-of-function mutations in voltage-gated potassium channels are major contributors to LQTS, impairing the outward potassium current crucial during phase 3 of the action potential. LQTS1 is linked to mutations in KCNQ1 (Kv7.1), LQTS2 to KCNH2 (Kv11.1), and LQTS5 and LQTS6 to β-subunit mutations (KCNE1, KCNE2). LQTS3 is caused by a gain-of-function mutation in SCN5A, enhancing the inward sodium current59,64. These autosomal dominant mutations prolong action potential duration, predisposing individuals to early afterdepolarizations and torsades de pointes (Fig. 20), while also increasing QT interval variability with HR changes. Additional genes (e.g., CALM1, CALM2, AKAP9) are also linked to LQTS65-68. A recessive form, caused by homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations in KCNQ1 and KCNE1, leads to Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome, characterized by very prolonged QT intervals, high risk of sudden death, congenital deafness, and poor beta-blocker response68.

Symptoms: symptoms often emerge in childhood or adolescence and include fainting, seizures, and SCD, typically due to VT and VF.

Diagnostic strategies: diagnosis is based on the Schwartz score (Table 6), with LQTS confirmed by QTc ≥ 480 ms, the presence of a pathogenic mutation, or an LQTS score > 369,70.

Table 6 Schwartz score for the diagnosis of LQTS

| Parameter | Points | |

|---|---|---|

| Electrocardiographic findings | ||

| A | QTca | |

| ≥ 480 ms | 3 | |

| 460 a 479 ms | 2 | |

| 450 a 459 ms (en varones) | 1 | |

| B | QTcb ≥ 480 ms. after 4 min of recovery in the exercise test | 1 |

| C | Torsade de Pointesc | 2 |

| D | T-wave alternans | 1 |

| E | Notched T-wave | 1 |

| F | Low heart rate for aged | 0.5 |

| Clinical manifestations | ||

| A | Syncopec | |

| With stress | 2 | |

| Without stress | 1 | |

| B | Congenital deafness | 0.5 |

| Family history | ||

| A | Family members with a definite LQTS diagnosise | 1 |

| B | Sudden cardiac death in a family member under 30 years | 0.5 |

≤ 1 point: low probability of LQTS.

From 1.5 to 3 points: intermediate probability of LQTS.

≥ 3.5 points: high probability of LQTS.

aIn the absence of medications or known causes affecting the QT interval.

bQTc calculated using Bazetts formula QTc=QTm/√RR.

cMutually exclusive.

dResting heart rate below the second percentile for age.

eThe same family member cannot be counted in both A and B.

Treatment strategies: all children with LQTS should avoid QT-prolonging medications (www.qtdrugs.org.), competitive sports, and correct electrolyte imbalances69,70. Beta-blockers are the first-line treatment, particularly effective in LQTS171. Left cardiac sympathetic denervation (LCSD) and sodium channel blockers, such as mexiletine may be considered in specific cases71. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) are reserved for those who survive VF or have arrhythmogenic syncope despite treatment71.

Special considerations: genetic counseling and continuous education are recommended for affected families to manage the condition effectively.

b) CPVT

Prevalence and mechanism: CPVT is an inherited channelopathy characterized by polymorphic ventricular arrhythmias triggered by exercise or emotional stress. Its prevalence is estimated at 1/10,000 but may be higher due to increased detection of RYR2 mutations in SCD cases27,28,71. Mutations in RYR2 (autosomal dominant) and CASQ2 (autosomal recessive) disrupt calcium handling in the sarcoplasmic reticulum, leading to stress-induced arrhythmias27-29,71.

Symptoms: symptoms of CPVT include syncope, pre-syncope, seizures, and SCD, often triggered by physical activity or emotional stress28.

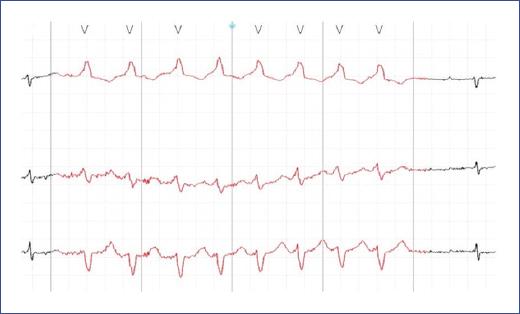

Diagnostic strategies: most patients have normal resting ECGs, but the stress exercise test is the gold standard for diagnosis, revealing ventricular ectopic beats that escalate to monomorphic or bidirectional VT (Fig. 21). Genetic testing for RYR2 and CASQ2 mutations is crucial for confirmation and family screening27.

Figure 21 ECG tracing during an exercise stress test in a 14-year-old patient with CPVT. The tracing begins with ventricular extrasystoles, which progressively increase in frequency and culminate in episodes of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. This pattern, characterized by varying QRS complex morphology and a rapid, irregular rhythm, is typical of CPVT during adrenergic stimulation, such as physical exertion, and underscores the high risk of sudden cardiac arrest associated with this condition. CPVT: catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia.

Treatment strategies: management includes exercise restriction and beta-blockers (nadolol or propranolol)72,73. Flecainide may be added if beta-blockers are insufficient. ICD placement is recommended for those resuscitated from CA, but its benefits are debated due to the risk of inappropriate shocks in children25,74. LCSD is an alternative for reducing arrhythmic events, especially when medical therapy fails.

Special considerations: patients require close monitoring, especially during stress. ICD programming should be carefully managed to avoid triggering arrhythmias. Genetic counseling, family screening, and education about CPVT management are essential.

c) BrS

Prevalence and mechanism: BrS is an autosomal dominant condition characterized by ST-segment elevation in right pre-cordial leads (Fig. 22) and life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias. It has a prevalence of 1 in 2,000-1 in 5,000, contributing to 10-20% of sudden infant deaths and 4-12% of SCD in children and young athletes. The Brugada ECG pattern often emerges post-puberty, even in initially negative cases, with fatal arrhythmias occurring in about 10% of affected children75-77. The condition is linked to mutations in SCN5A and other genes, with most diagnoses made through family screening71,77.

Figure 22 Electrocardiogram of an adolescent with Brugada syndrome showing characteristic coved-type ST-segment elevation in leads V1-V3, indicative of a high risk for ventricular arrhythmias.

Symptoms: children with BrS may experience syncope, palpitations, dizziness, dyspnea, and SCD, often triggered by fever or vaccination76. A positive family history is a common initial clue.

Diagnostic strategies: diagnosis involves detecting SCN5A mutations, family history, and pediatric ECG, with Holter monitoring to identify ECG abnormalities. Fever can exacerbate ECG abnormalities77.

Treatment strategies: quinidine is the primary medication, while ICD placement is recommended for those with a history of CA, sustained VT, or spontaneous type 1 ECG patterns (Fig. 22) with syncope. Challenges with ICDs in children include device-related complications and the need for careful programming to prevent inappropriate shocks75,77.

Special considerations: AF episodes in children may indicate BrS and fever management is crucial. Families should be educated on avoiding medications that increase BrS risks, with guidance available at www.brugadadrugs.org.

d) Short QT syndrome (SQTS)

Prevalence and mechanism: SQTS is a rare inherited channelopathy characterized by abnormally shortened QT intervals (Fig. 23), leading to arrhythmias and SCD. It follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern and is associated with mutations in eight genes regulating ionic currents59,78. Prevalence ranges from 0.02% to 0.1% in adults and up to 0.05% in children, with a high incidence of arrhythmic events during infancy. The syndromes fatality rate is significant, with a 40% cumulative risk of cardiac events by age 40, predominantly in males78.

Figure 23 Electrocardiographic tracing of a young child with short QT syndrome. Note the shortened QT interval (measured at 320 ms), indicating the characteristic feature of the syndrome. The tracing shows a typical rapid repolarization pattern associated with this condition.

Symptoms: SQTS manifests in nearly 40% of patients, with symptoms including palpitations, AF, ventricular arrhythmias (VT/VF), syncope, and SCD, especially in infancy and between ages 20 and 40.

Diagnostic strategies: diagnosis is recommended when QTc ≤ 360 ms, along with a pathogenic mutation, family history of SQTS, SCD, or survival from VT/VF59. Table 7 shows a diagnostic scoring system for SQTS proposed by Gollob et al. Genetic testing can identify pathogenic variants in approximately 30% of cases, with five genes (KCNH2, KCNJ2, KCNQ1, CACNA1C, and CACNB2B) recommended for evaluation. ECG changes include minimal or absent ST segments, tall T waves, and short J-T peak intervals.

Table 7 Diagnostic scoring system for short qt syndrome proposed by Gollob et al.

| Electrocardiographic findings | Points |

|---|---|

| QTc^ | |

| < 370 ms | 1 |

| < 350 ms | 2 |

| < 330 ms | 3 |

| Jpoint-Tpeak interval < 120 ms* | 1 |

| Clinical history# | Points |

| Sudden death† | 2 |

| Polymorphic ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation† | 2 |

| Unexplained syncope† | 1 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1 |

| Family history# | Points |

| First- or second-degree relative with a high probability of SQTS | 2 |

| First- or second-degree relative with unexplained sudden death | 1 |

| Relative with sudden infant death | 1 |

| Genotype‡ | Points |

| Positive genotype | 2 |

| Variant of uncertain significance in genes associated with SQTS | 1 |

^QTc calculated using Bazetts formula (QTc = QT/√RR).

*Measure in the precordial lead with the highest T wave amplitude.

#A minimum of 1 point must be obtained in the electrocardiographic section to earn additional points.

†Mutually exclusive.

‡Points can only be received once in this section.

≤ 2 points: low probability; 3 points: intermediate probability; ≥ 4 points: high probability.

Treatment strategies: ICD therapy is indicated for survivors of aborted CA and patients with documented spontaneous VT. In asymptomatic patients, risk stratification is challenging, with ICDs considered for those with arrhythmic syncope78. Pharmacological therapies with QTc-prolonging drugs, such as quinidine may be used in patients who cannot receive or decline ICDs. Implantable loop recorders (ILRs) are recommended for monitoring in asymptomatic children.

Special considerations: genetic counseling and family screening are crucial due to the hereditary nature of SQTS. Patients should be educated about the syndrome, its triggers, and management strategies, with a multidisciplinary approach involving cardiologists, geneticists, and electrophysiologists for comprehensive care.

Discussion

This comprehensive review presents a symptom-based framework designed to assist non-specialist physicians in managing pediatric arrhythmias, emphasizing the importance of tailored approaches that consider the unique physiological and genetic factors in children. Pediatric arrhythmias vary significantly, with many asymptomatic cases being benign. However, certain conditions, such as pre-excitation syndrome and LQTS, require vigilant monitoring due to the risk of severe complications2,41,67.

Paroxysmal tachycardia, particularly SVT, is commonly encountered in pediatric patients. Initial management typically includes non-pharmacological interventions, with adenosine as the first-line pharmacological treatment36. In unstable patients, electrical cardioversion is recommended22,30,37,54.

IAs, including LQTS, BrS, CPVT, and SQTS, present significant risks even in the absence of structural heart disease4,59. In these cases, genetic testing and family screening are crucial, with NGS enhancing the detection of pathogenic variants. However, many of these variants remain classified as VUSs, necessitating further research to clarify their clinical implications71,73.

Pediatric arrhythmia management encompasses a range of strategies, including lifestyle modifications, pharmacological treatments, and interventional procedures such as catheter ablation and ICD placement. Beta-blockers play a central role in managing conditions, such as LQTS and CPVT5,25,43,49,72,79, while ICDs, although lifesaving, present challenges in children, including device-related complications and the need for meticulous programming to minimize risks5,19,74.

Since non-electrophysiology specialists are often the first to evaluate children presenting with arrhythmias and specific symptoms, this practical guide on the initial approach is highly valuable for ensuring appropriate treatment and timely, effective referral to specialized centers. Effective referral involves identifying cases at high risk for serious complications, including SCD, while managing benign casescommon in the pediatric populationwith a conservative and vigilant approach, avoiding the use of antiarrhythmic medications that may be more harmful than beneficial.

Looking ahead, our findings highlight several areas in need of further research and improvement in clinical practice. There is a pressing need for more extensive pediatric-specific studies to develop evidence-based guidelines tailored specifically to children. In addition, continued advancements in genetic research are essential to clarify the clinical relevance of VUSs and to develop novel therapeutic interventions for managing IAs. By addressing these gaps, we can improve the care and outcomes for children affected by arrhythmias.

Limitations

Despite the comprehensive nature of this review, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the reliance on existing literature may introduce bias, as studies with positive outcomes are more likely to be published. Second, the heterogeneity in study designs, patient populations, and diagnostic criteria across the included studies may limit the generalizability of our findings. In addition, the brief period of included studies (2019-2024) may exclude relevant research published outside this period. Finally, while this review aims to provide practical guidelines for non-specialist physicians, the rapidly evolving field of pediatric cardiology necessitates ongoing updates to ensure recommendations remain present and evidence-based.

Conclusion

This review underscores the complexity of pediatric arrhythmias and the importance of a symptom-based approach in their management. By synthesizing the present evidence and providing practical guidelines, we aim to equip non-specialist physicians with the tools necessary to effectively diagnose and treat pediatric arrhythmias, improving patient outcomes and reducing the incidence of SCD in this vulnerable population.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)