Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is the leading cause of death or severe disability in children; according to its severity, it increases susceptibility to functional deficits, cognitive impairment, and mental health problems1.

Epidemiology

TBI is the most frequent cause of death and disability in children over 1 year of age. The mortality rate is higher in children under 4 years old compared to those aged 5-14 years2. The most common causes of TBI are falls in children under 14 years, followed by abuse in children under 2 years, and traffic accidents3. Up to 61% of children with moderate or severe head trauma will experience some degree of disability2,4,5.

Definition and Classification

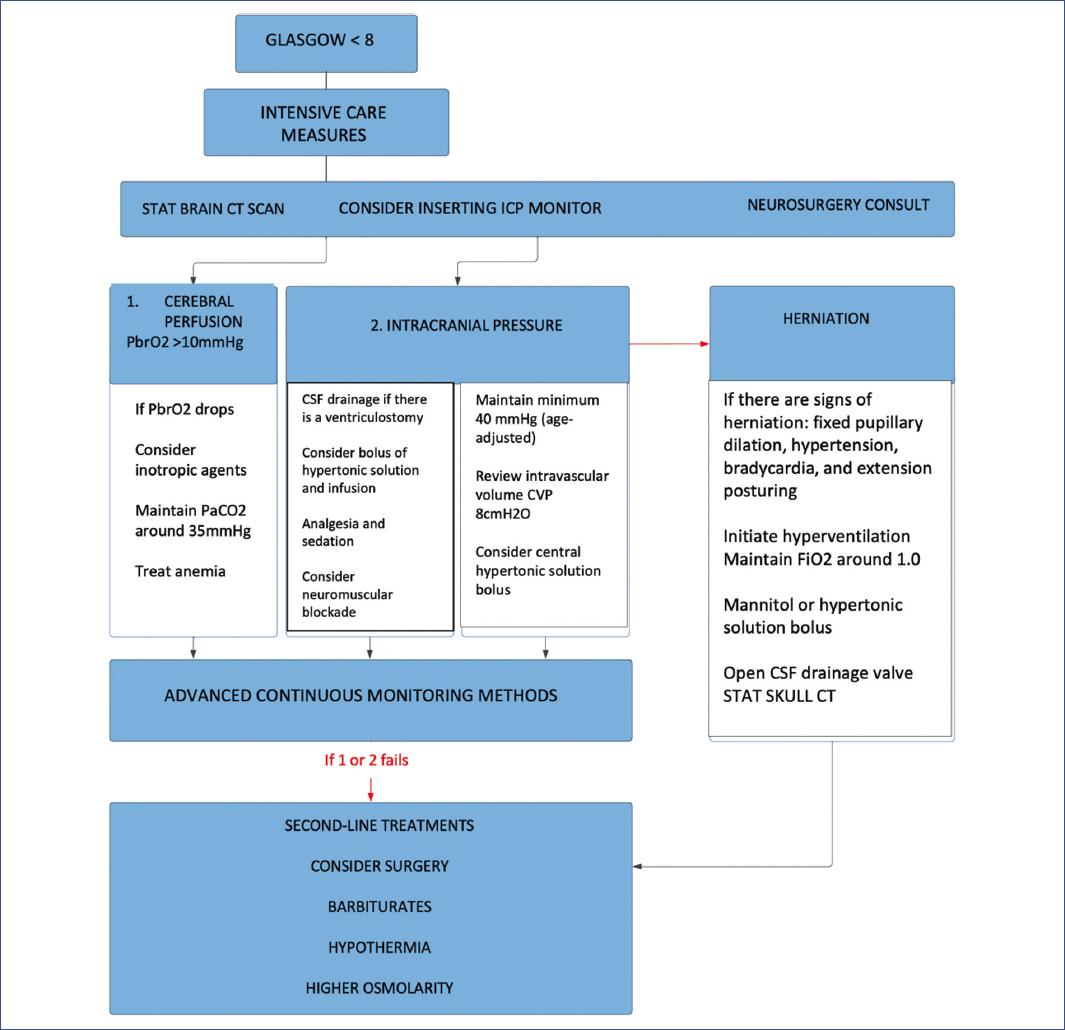

TBI is defined as injury to the structures of the head due to an external mechanical force, with or without interruption of structural continuity2,3. The most accepted classification based on severity uses the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), defining mild TBI as a GCS score of 14-15, moderate TBI as a GCS score of 9-13, and severe TBI as a GCS score below 84.

Several international guidelines have been published in recent years, but they may not necessarily apply in Latin America. In this regard, AINP (for its Spanish acronym) recently approved guidelines for the treatment of head trauma in children in our region.

Materials and methods

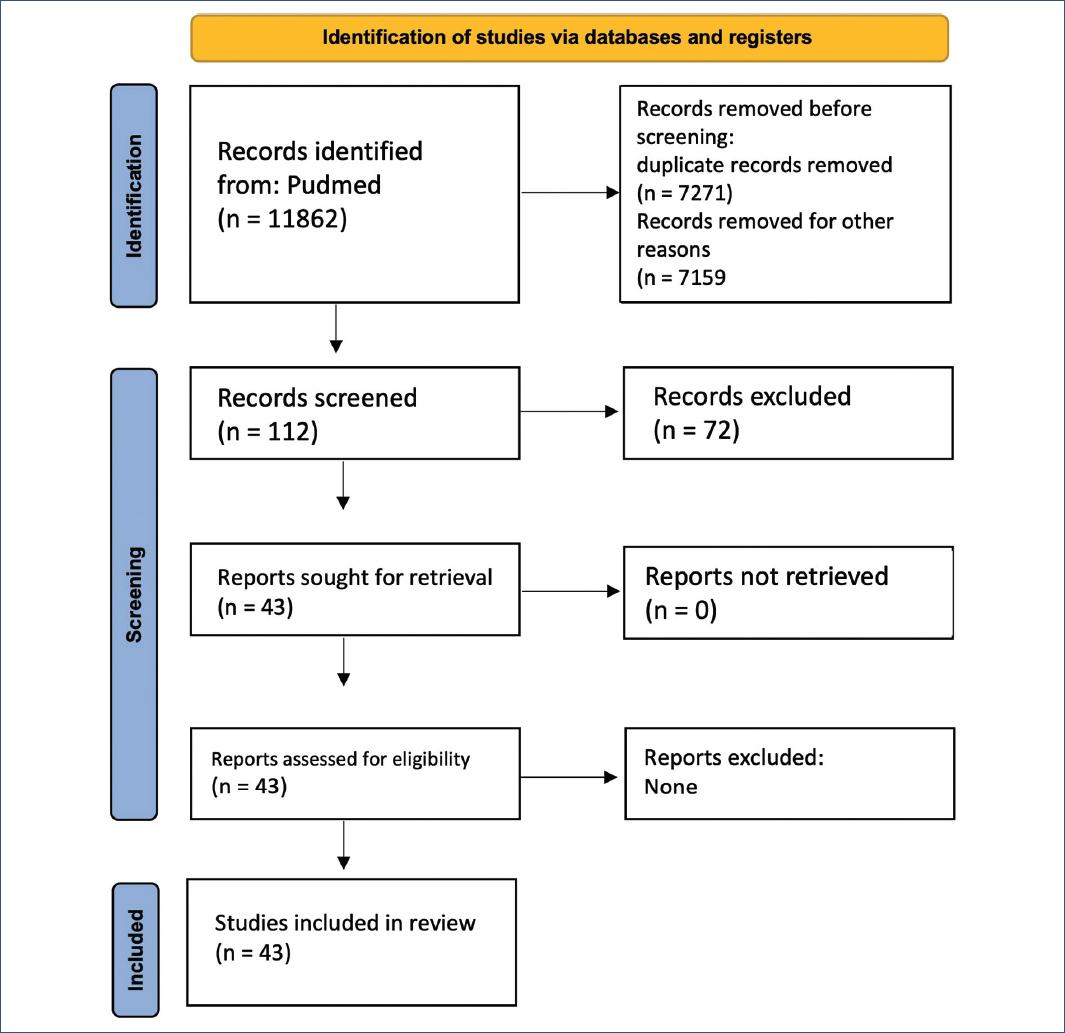

A systematic review was conducted using the PRISMA protocol (Fig. 1). Studies written in English or Spanish were selected. Animal studies and articles that did not meet the objectives of our study were excluded. Only studies on mild, moderate, or severe pediatric head trauma that included an analysis of TBIs in pediatric patients were included. Topics with the most substantial evidence were chosen to seek the best available information, and management results were analyzed to produce valid conclusions.

Figure 1 PRISMA flow diagram for a systematic review of pediatric traumatic brain injury management. Identification, screening, and inclusion process

For this systematic literature review, the PubMed database was used. The search was conducted between January 1 and March 30, 2023. We used an advanced search strategy with the following terms: (“trauma” [Title/Abstract] AND “pediatric” [Title/Abstract] AND “management” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“traumatic brain injury” [Title/Abstract] AND “pediatric” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“head” [Title/Abstract] AND “pediatric” [Title/Abstract] AND “guides” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“injuries” [Title/Abstract] AND “pediatric” [Title/Abstract] AND “Recommendations” [Title/Abstract]).

Data extraction and analysis

The following information was collected from each article: author/year, methods, number of participants, and study design. Main results were also extracted, including outcome measures and the main limitations of each study. The primary and secondary objectives of the studies were analyzed, and the main conclusions of each study were collected.

The ROBINS-I tool was used to assess bias in observational studies. The selected articles on the management of TBI in pediatrics were re-analyzed according to the latest available scientific evidence and selected according to the 2011 version of Oxford Levels of Evidence.

Results

Due to its accessibility, rapid acquisition, and diagnostic performance, computed tomography (CT) of the skull is the imaging modality of choice for moderate and severe pediatric TBI.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is indicated when the clinical scenario remains unclear, when there is a clinical-radiological dissociation, after performing a CT, and in clinically stable children. It allows better identification of contusions and diffuses axonal injury.

Specialized guidelines, such as the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network, are used in mild trauma to select the population requiring emergency imaging and reduce radiation exposure.

Two systematic reviews with a recommendation grade A and evidence level 1a6,7 and then “feasibility and accuracy of rapid MRI versus CT for TBI in young children”8 and two retrospective studies9 and “risk factors associated with TBI and application of guidelines for requesting CT after TBI in children in France”10 have evidence level 1b.

Routine follow-up CT scans are not recommended unless there is evidence of increased intracranial pressure (ICP) or neurological deterioration. We found two systematic reviews of cohort studies with homogeneity, with evidence level 2a and a recommendation grade B11,12.

Appropriate level of analgesia and sedation

The use of a combination of benzodiazepine and opioids is recommended for the initial management of TBI; the use of midazolam and morphine or fentanyl is suggested. We found a systematic review, “Management of severe pediatric TBI: 2019 consensus and guideline-based algorithm for the first and second tier therapies”13 with evidence level 2a, and an article reflecting expert opinion, “Differences in medical therapy goals for children with severe TBI: an international study” with evidence level 5, but both with recommendation grade B.

Controlled mechanical ventilation

The suggested ventilatory goals are PaO2: 90-100 mmHg and PaCO2 between 35 and 40 mmHg. An article with evidence level 2a and recommendation grade B was found13.

Maintenance of normothermia and fever prevention

Post-traumatic temperature elevations have been shown to increase inflammatory processes, including elevation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and increased neutrophil accumulation in injured tissue. It is recommended to maintain normothermia with values above 35°C and below 38°C. We selected two systematic review studies of cohort studies with homogeneity, with evidence level 2a and recommendation grade B: severe TBI management: evidence-based medicine guideline13-15.

Appropriate intravascular volume status

To address normovolemia, at least 75% of maintenance fluids and a neutral fluid balance are required, with a urine flow rate of more than 1 mL/kg/h. The use of 0.9% saline solution is recommended in the initial fluid prescription; to avoid the risk of hypoglycemia, the initial use of 5% dextrose in IV saline infusion is suggested in infant patients. Two systematic reviews of cohort studies with homogeneity represent the best evidence and have evidence level 2a and recommendation grade B13,16.

Nutritional support

Early initiation of enteral nutritional support (within 72-h post-injury) is suggested to decrease mortality and improve outcomes. This recommendation is supported by a systematic review of homogeneous cohort studies: “Guidelines for the management of pediatric severe TBI, third edition: Update of the brain trauma foundation guidelines”17 which have evidence level 2a and recommendation grade B.

Treatment with antiepileptic drugs and continuous EEG (cEEG) use

Prophylactic treatment is suggested to reduce the incidence of early post-traumatic seizures (within 7-day post-trauma), both clinical and subclinical. There is insufficient evidence to recommend levetiracetam over phenytoin based on efficacy for post-traumatic seizure prevention. The scientific basis comes from six systematic reviews of cohort studies with homogeneity: “Early use of antiseizure medication in mechanically ventilated TBI cases: A retrospective pediatric health information system database study”18, “Anti-epileptic prophylaxis for early or late post-traumatic seizures in children with TBI: A systematic review”19, and “Severe TBI management: Evidence-based medicine guideline”15 and three more by Kochanek mentioned above in the text. All have evidence level 2a and recommendation grade B12,13,17.

cEEG use

Evidence supports its use throughout management, particularly when neuromuscular blockade is used. However, there is insufficient data to confirm that seizure treatment improves brain injury outcomes, as noted by the analysis of two systematic reviews of cohort studies with homogeneity with evidence level 2a and recommendation grade B, but also an expert opinion: “Consensus statement on cEEG in critically ill adults and children, part I: indications”13,15,20.

ICP monitoring during severe TBI

ICP measurement is recommended to determine if there is intracranial hypertension (ICH). Since much of current care is based on preventing and treating elevated ICP, early detection of elevated ICP with monitoring is considered to allow timely administration and precise treatment titration compared to management without an ICP monitor. Certain studies support the association of successful control of ICH based on ICP monitoring with better survival and neurological outcomes.

We selected four systematic reviews of cohort studies with homogeneity with evidence level 2a, a propensity-weighted effectiveness analysis study with evidence level 2b, and a retrospective observational study: “Functional outcome after ICP monitoring in children with severe TBI”12,13,15,17,21,22.

Advanced neuromonitoring

If brain tissue oxygen partial pressure (PbrO2) monitoring is used, it is suggested to maintain a level > 10 mmHg. However, we do not have sufficient evidence to support a recommendation for the use of a brain interstitial PO2 (PbrO2) monitor to improve outcomes.

The use of advanced neuromonitoring should only be for patients without contraindications for invasive neuromonitoring, such as coagulopathy, and for patients who do not have a diagnosis of brain death.

A systematic review of cohort studies with homogeneity by Kochanek et al. provides evidence level 2a and a recommendation grade B17.

Treatment thresholds

An ICP goal of < 20 mmHg is suggested to improve overall outcomes. Preventing ICH is important to avoid cerebral herniation events, which can trigger a cascade of often fatal sequelae.

A systematic review of cohort studies with homogeneity: “Guidelines for the management of pediatric severe TBI, third edition: Update of the brain trauma foundation guidelines”17, a prospective observational study with evidence level 2b, “ICH and cerebral hypoperfusion in children with severe TBI: Thresholds and burden in accidental and abusive insults”23, and a retrospective observational study, “Relationship of ICP and cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) with outcome in young children after severe TBI”24, with evidence level 3b and a recommendation grade B for all three.

CPP thresholds

Treatment should aim to keep the CPP at a minimum of 40 mmHg. The strongest evidence comes from a prospective observational cohort study with evidence level 1b and recommendation grade A, a systematic review of cohort studies showing homogeneity with evidence level 2a and recommendation grade B, a prospective observational study with evidence level 2b and recommendation grade B, and a retrospective observational study with evidence level 3b and recommendation grade B17,23-25.

Treatment of elevated ICP

Intervention is recommended when ICP rises to more than 20 mmHg for at least 5 min, whereas a gradual progression of interventions is warranted for an ICP elevation between 20 and 25 mmHg.

Hyperosmolar therapy

For ICP control, it is recommended to administer boluses or continuous infusion of 3% hypertonic saline solution. The recommended effective doses for the acute use of 3% hypertonic solution boluses range between 2 and 5 mL/kg over 10-20 min. Similarly, the suggested effective doses for continuous infusion of 3% saline solution range between 0.1 and 1.0 mL/kg body weight per hour. Administering the minimum dose necessary to maintain ICP below 20 mmHg is important. In cases of refractory ICP, a bolus of 23.4% hypertonic saline solution is recommended, with a suggested dose of 0.5 mL/kg and a maximum of 30 mL26.

In the context of multiple ICP-related therapies, sustained serum sodium levels (> 72 h) above 170 mEq/l are suggested to prevent complications of thrombocytopenia and anemia, whereas sustained serum sodium levels above 160 mEq/l are suggested to prevent deep vein thrombosis26.

Although mannitol is commonly used to treat elevated ICP in pediatric TBI, no studies were identified that met the inclusion criteria for its use as evidence for this topic. If used, mannitol should be administered as a bolus (0.5-1 g/kg) over 10 min, and blood pressure should be monitored, as arterial hypotension should be avoided.

Three systematic reviews of cohort studies with homogeneity were published by Kochanek, one by Carney: “Guidelines for the Management of Severe TBI, Fourth Edition” and one by Birrer: “Severe TBI management: Evidence-based medicine guideline” provide evidence level 2a, and a systematic review: “Current Management of Pediatric TBI” had evidence level 2b12,13,15,17,27.

Three retrospective observational studies: “Hyperosmolar Therapy in Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury: A Retrospective Study,” “Hypertonic Saline in Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury: A 9-Year Review of Experience with 23.4% Hypertonic Saline as Standard Hyperosmolar Therapy,” “Clinical Indicators of Intensive Care Associated with Discharge Outcomes in Children with Severe Traumatic Brain Injury,” one standard, one cohort, and one multicenter, and a systematic review indicated evidence level 2b, but all have recommendation grade B26,28-30.

Analgesics, sedatives, and neuromuscular blockade for ICP control

In the treatment of ICH, if therapy is ineffective, additional analgesia and sedation should be considered, along with the possible initiation of neuromuscular blockade. It is suggested to avoid bolus administration of midazolam and/or fentanyl during ICP crises due to the risks of cerebral hypoperfusion. According to FDA recommendations, prolonged continuous infusion of propofol is not indicated for sedation or treatment of refractory ICH. In the absence of evidence, specific indications, choice, and dosage of analgesics, sedatives, and neuromuscular blockers should be left to the treating physician.

Three systematic review articles of cohort studies with homogeneity, a systematic review with evidence level 2a, a retrospective cohort study with evidence level 2b, a systematic review with evidence level 2b, and a prospective observational study with evidence level 2c provide the evidence supporting this grade B recommendation12,13,15,17,26,31,32.

CSF drainage

External ventricular drainage can be used to measure ICP in children after TBI and may provide additional therapeutic benefits from CSF drainage. CSF drainage through an external ventricular drain is suggested to control increased ICP and improve outcomes in children with severe TBI. Refractory elevated ICP contributes to mortality; therefore, controlling elevated ICP is an important factor in patient survival after severe TBI.

Four systematic review studies of cohort studies with homogeneity, evidence level 2a, and a prospective observational study, evidence level 2c, provide these grade B recommendations12,13,15,17,33.

Ventilation therapies

Severe prophylactic hyperventilation to a PaCO2 < 30 mmHg is not recommended in the first 48 h after injury. If hyperventilation is used in the treatment of refractory ICH, advanced neuromonitoring is suggested for the evaluation of cerebral ischemia. Three systematic review studies of cohort studies with homogeneity with evidence level 2a and a retrospective cohort study with evidence level 2b provide these grade B recommendations12,13,17,34.

Second-line therapies

TEMPERATURE CONTROL/HYPOTHERMIA

Prophylactic moderate hypothermia (32-33°C) is not recommended over normothermia for improving overall outcomes. The late application of moderate hypothermia during the second-tier management stage is used as an option to control refractory ICH. The target temperature is 32-33°C or 34-35°C. If hypothermia is used and rewarming is initiated, it should be performed at a rate of 0.5-1.0°C every 12-24 h or more slowly to avoid complications.

If phenytoin is used during hypothermia, it is suggested to monitor and adjust the dose to minimize toxicity, especially during the rewarming period.

A multicenter prospective randomized controlled phase II trial provides level 1b evidence and grade A recommendation, whereas five systematic reviews of cohort studies with homogeneity and a meta-analysis with evidence level 2a provide grade B recommendations12,13,15,17,35-37.

BARBITURATES

High-dose barbiturate treatment is suggested in hemodynamically stable patients with refractory ICH despite maximum medical and surgical treatment. Continuous blood pressure monitoring and cardiovascular support are required to maintain adequate CPP. If barbiturate infusion fails to control ICP, decompressive craniectomy or other second-tier therapies should be considered.

Four systematic reviews of cohort studies with homogeneity providing evidence level 2a, one systematic review and one retrospective cohort study with evidence level 2b provide the scientific basis for these grade B recommendations12,13,15,17,26,38.

DECOMPRESSIVE CRANIECTOMY

Decompressive craniectomy is suggested to treat neurological deterioration, herniation, or ICH refractory to medical treatment. An extensive fronto-temporoparietal craniectomy (12 × 15 cm or 15 cm in diameter) is recommended over a smaller one. It is suggested that secondary decompressive craniectomy, performed as a treatment for early or late refractory ICP elevation, reduces ICP and the duration of intensive care, although the relationship between these effects and favorable outcomes is uncertain. The evidence for the benefit of this procedure is not entirely clear, and risks versus benefits should always be weighed.

Two prospective cohort studies with evidence level 1b and grade A recommendation, four systematic reviews of cohort studies with homogeneity, and one systematic review with evidence level 2a and grade B recommendation, a systematic review of “Current management of pediatric traumatic brain injury” with evidence level 2b and grade B recommendation, a retrospective descriptive study and a literature review with evidence level 4 and grade C recommendation, and an article reflecting expert opinion: “Long-term outcome after decompressive craniectomy: an uncomfortable truth?” were analyzed for these recommendations12,13,15,17,26,39,40.

CORTICOSTEROIDS

The use of corticosteroids is not suggested to improve outcomes or reduce ICP. For these recommendations, three studies by Kochanek and one by Birrer were taken as scientific bases, as systematic reviews of cohort studies with homogeneity, with evidence level 2a and grade B recommendation, and a systematic review by Raikot et al., with evidence level 2b and grade B recommendation12,13,15-17.

Conclusions

The increase in scientific evidence regarding the treatment, prognosis, and follow-up of patients with severe pediatric TBI contributes to developing evidence-based recommendations for implementing reliable protocols that can be adapted to multiple settings. Although evidence is still insufficient, guidelines for severe pediatric TBI have been updated to include better treatment options.

Further future research is still required to confirm the efficacy of current recommendations in the pediatric age group to improve the prognosis of children who suffer severe cranial injury.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)