Introduction

The current paradigm of diagnosis and treatment of patients suffering an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) recommends classifying them according to the presence or absence of persistent ST-segment elevation as ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction (or STEMI) and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (or NSTEMI)1. This paradigm is primarily based on the fact that patients with STEMI often show the presence of a total (or quasi-total) acute coronary thrombotic occlusion as the pathophysiological substrate for their condition2, and that patients with ST elevation have consistently been found to benefit with reperfusion therapy administered as soon as possible and preferentially during the first 12 h since symptom onset1-3.

However, this classification shows important limitations: large series have documented that up to 30% of patients initially classified as NSTEMI will show evidence of total coronary occlusion on index angiography4,5; similarly, more than a third (depending on the initial assessment scenario) of patients initially diagnosed with STEMI may show a final different diagnosis, such as myopericarditis, left bundle branch block, etc6. Of utmost concern is the subgroup of patients experiencing the so-called acute coronary occlusion myocardial infarction (ACOMI), who are initially classified as NSTEMI (due the lack of clear ST elevation in their index and subsequent electrocardiogram [ECGs]) which in turn are found to have an acute total (or quasi-total) coronary thrombotic occlusion as the infarction culprit lesion, and show increased length of stay, use of hospital resources and a higher short and long-term mortality7. Therefore, prompt detection of ACOMI is paramount for health-care providers in acute care settings.

Artificial intelligence (AI) holds promise in this regard, as AI-ECG-based models have demonstrated proficiency in identifying conditions like severe left ventricular dysfunction and atrial fibrillation in patients with sinus rhythm, as well as predicting outcomes such as septic shock in continuous hospital admissions8, among other various examples. Previous studies have shown that AI-ECG-based algorithms can exceed the diagnostic accuracy of trained cardiologists and detect conditions that may otherwise remain undetected9-16,20-22. We therefore aimed to derive an AI-ECG-based algorithm capable of detecting ACOMI in the setting of patients initially diagnosed with NSTEMI.

Materials and methods

Study design and population

This was a prospective, observational, longitudinal, single-center study including patients aged 18 years or more with the initial diagnosis of ACS (both STEMI & NSTEMI). Patients were selected from the study center database and their ECGs were acquired for the study; for maximization of the study objective (the detection of ACOMI) we aimed to include a proportion of at least 50% of patients showing ACOMI on initial coronary angiography. Patients with no coronary angiography, incomplete baseline information, or no ECG recorded before coronary angiography were excluded. The study received institutional research and ethics committee approval (local registration number 21-1265) and complies with the Helsinki Declaration.

Data collection and AI model training

To train the deep learning model for recognizing ACOMI, we manually digitized patients' ECGs using smartphone cameras of varying quality. The resulting images exhibited significant variability in dimensions, ranging from 595 to 4032 pixels in width and 344 to 3024 pixels in height. To ensure uniformity, all images were standardized to a size of 256 × 256 pixels. The images were stored in RGB format, each containing three channels. Personal and sensitive patient information was cropped out to ensure privacy, and all ECG analyses were conducted blind to patient identity, angiographic findings, and clinical outcomes.

DATA PROCESSING AND CLASSIFICATION

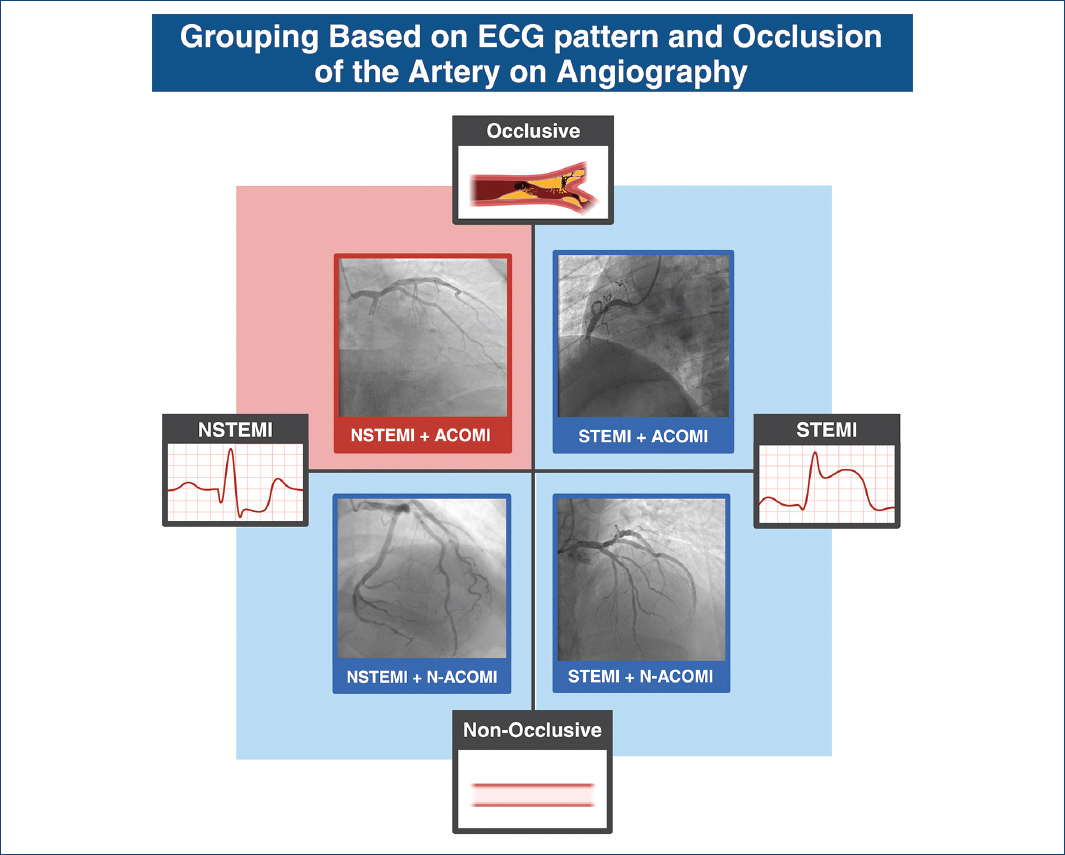

The ECG images were categorized by the investigators into four classes:

NSTEMI + ACOMI

STEMI + ACOMI

STEMI + no ACOMI

NSTEMI + no ACOMI across subsets (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 Classification of patients based on the presence or absence of ST-elevation and total coronary occlusion.

The dataset was then randomly divided into subsets: 81% for training, 9% for validation, and 10% for testing. Stratification was employed to preserve the proportional distribution of the classes across subsets.

MODEL DEVELOPMENT

We utilized convolutional neural networks as the core AI models for ECG classification. Due to the relatively small size of our dataset, we adopted a transfer learning strategy. Transfer learning leverages a pre-trained model, initially developed using a large, generic dataset and fine-tunes its parameters for a more specific application. This approach is particularly advantageous when training data are limited, as it builds on the model's pre-existing knowledge, requiring minimal adjustments for the new task17.

The InceptionResNetV218 architecture, pre-trained on the ImageNet19 database, was selected for our analysis. This model is a deep convolutional network with 449 layers and approximately 55.9 million parameters. In our implementation, we utilized only its convolutional blocks, adding a Global Average Pooling (GAP) layer followed by three fully connected layers with 1024, 512, and 4 units, respectively.

– The 1024- and 512-unit layers employed ReLU as the activation function to capture complex patterns

– The final output layer, consisting of 4 units, used the softmax function to generate class probabilities in a one-hot encoding format. For instance, an image from class 3 would be represented as (0, 0, 1, 0).

TRAINING PROTOCOL

The model was trained using the Adam optimizer and the categorical cross-entropy loss function. Training was conducted in batches of 64 over 30 epochs. During this process, the parameters of the base InceptionResNetV2 model remained frozen, and only the parameters of the newly added dense layers were optimized. This strategy ensured that the robust features extracted by the pre-trained convolutional layers were preserved, while the dense layers were fine-tuned to recognize ECG-specific features relevant to ACOMI classification. For educational purposes, supplementary appendix 1 includes the description, with pertinent examples, of the ML methodology used in the present study.

ECG interpretation by experts

Electrocardiograms were evaluated by two independent expert cardiologists, blinded to clinical outcomes and results of coronary angiography. Each observer was presented with the images and asked to determine whether the patient had (1) a STEMI, based on the criteria of the fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction and current clinical practice guidelines1 and (2) the suspicion of ACOMI based on his expertise and the presence of high-risk findings (such as De Winter pattern, subtle ST elevation, or other findings).

ACOMI definition

ACOMI was defined by coronary angiography findings meeting any of the following three criteria: a) total thrombotic occlusion, b) TIMI thrombus grade 2 or higher + TIMI grade flow 1 or less, or c) the presence of a subocclusive lesion (> 95% angiographic stenosis) with TIMI grade flow < 3. Baseline clinical characteristics were registered for all included patients and are presented according to the previous categorization.

Study objectives

The primary objective of the present study was to test the AI-ECG model area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for the detection of ACOMI in patients with both STEMI & NSTEMI and to compare it with (1) STEMI criteria area under the ROC curve & (2) Expert's criteria area under the ROC curve. The secondary objective was to compare the sensitivity, specificity, positive, and negative predictive values of the AI-ECG model with STEMI & Expert's criteria.

Statistical analysis

For the assessment of baseline clinical characteristics, we described and compared quantitative variables based on their distribution according to the previously defined groups. Normally distributed variables, assessed by the Shapiro–Wilk test, were reported as means and standard deviations, and comparisons were made using Student's t-test. Non-normally distributed variables were presented with medians and interquartile ranges, and comparisons were performed using Mann-Whitney's test. Categorical variables were described with frequencies and percentages and compared using the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test. The performance of the AI-ECG-based algorithm compared to the evaluation of our ECG experts was evaluated with the multiple areas under the ROC curves comparison, expressed as central tendency and 95% confidence interval (CI). The p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA v14.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

Baseline characteristics and prevalence of ACOMI

A total of 362 patients and their respective ECGs were selected and included in the present study. Among these, distribution of NSTEMI + ACOMI, STEMI + ACOMI, STEMI + no ACOMI, NSTEMI + no ACOMI was 48%, 7%, 19%, and 26%. Patients were 62.95 ± 11.57 years old, 80.47% were male; the prevalence of diabetes was 41.71%, hypertension 52.71%, and dyslipidemia 28.45%. Table 1 shows the baseline clinical characteristics of the study patients stratified according to the index diagnosis and the presence or absence of ACOMI. Patients initially classified as NSTEMI and subsequently found with ACOMI criteria showed an initial TIMI flow of 0-1 in 49% of the cases and the presence of TIMI 1-4 in 92% of cases. Patients with ACOMI were less likely to have hypertension (46.7% vs. 60.7%, p = 0.009), diabetes (36.6% vs. 49.0%, p = 0.01), and more likely obese (29.1% vs. 20.5%, p = 0.04).

Table 1 Baseline clinical characteristics

| Characteristics | ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction(96) | non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction(262) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (27) ACOMI | (69) NO ACOMI | (172) ACOMI | (94) NO ACOMI | ||

| Demographic characteristics | |||||

| Age, years | 57.59 ± 8.71 | 58.05 ± 12.15 | 62.95 ± 11.57 | 65.21 ± 10.94 | 0.001 |

| Male, n (%) | 21 (77.78) | 52 (75.36) | 136 (80.47) | 69 (73.40) | 0.792 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Diabetes, n (%) | 10 (37.04) | 30 (43.48) | 61 (36.09) | 50 (53.19) | 0.085 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 13 (48.15) | 34 (49.28) | 79 (46.75) | 65 (69.15) | 0.004 |

| Active smoker, n (%) | 13 (48.15) | 33 (47.83) | 57 (33.73) | 37 (39.36) | 0.193 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 8 (29.63) | 12 (17.39) | 53 (31.36) | 30 (31.91) | 0.075 |

| Obesity, n (%) | 9 (33.33) | 14 (20.29) | 49 (29.17) | 19 (20.21) | 0.287 |

| Clinical presentation | |||||

| Heart rate (bpm) | 80 (72-92) | 74 (66-89) | 75 (65-88) | 77 (69-90) | 0.667 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 134 (124-140) | 127 (113-137) | 136 (120-155) | 133 (116-155) | 0.002 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 77 (70-85) | 75 (70-84) | 80 (70-90) | 80 (70-90) | 0.020 |

| Respiratory rate (bpm) | 18 (16-20) | 18 (16-20) | 18 (16-18) | 18 (16-20) | 0.007 |

| SpO2 (%) | 94 (91-96) | 94 (92-96) | 94 (92-96) | 93 (91-95) | 0.048 |

| Killip Kimball | |||||

| 1, n (%) | 19 (70.37) | 50 (72.46) | 135 (79.88) | 76 (80.85) | |

| > 1, n (%) | 8 (29.63) | 19 (27.54) | 34 (20.12) | 18 (19.15) | 0.4033 |

| GRACE | 110 (94-134) | 108 (97-129) | 101 (84-122) | 107 (88-134) | 0.0232 |

| Medical history | |||||

| Previous IM | 4 (14.81) | 9 (13.04) | 49 (29.17) | 39 (41.49) | < 0.001 |

| Previous PCI | 2 (7.41) | 6 (8.70) | 26 (15.48) | 24 (25.53) | 0.013 |

| Cardiac biomarkers | |||||

| High-sensitivity troponin (ng/L) | 6765 (815-14163) | 5292 (1251-8583) | 517 (76.7-2145) | 592.5 (176-1239) | 0.0001 |

| NT-ProBNP (pg/mL) | 648 (301-2111) | 1145 (373-3093.5) | 743 (209-1976) | 1626.5 (504-4929) | 0.0133 |

| Angiographic characteristics | |||||

| Final TIMI | |||||

| 0 | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (1.45) | 0 (0.00) | 0.5399 |

| 1 | 2 (7.41) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (1.45) | 0 (0.00) | |

| 2 | 3 (11.11) | 5 (7.25) | 22 (15.94) | 11 (13.25) | |

| 3 | 22 (81.48) | 64 (92.75) | 112 (81.16) | 72 (86.75) | |

| Culprit artery | |||||

| LAD | 15 (55.56) | 34 (49.28) | 69 (40.83) | 53 (56.38) | 0.0794 |

| RCA | 11 (40.74) | 31 (44.93) | 62 (36.39) | 22 (23.40) | 0.0272 |

| Cx | 1 (3.70) | 4 (5.80) | 38 (22.49) | 18 (19.15) | 0.0036 |

| Echocardiographic features | |||||

| LVEF, n (%) | 45 (28-51) | 45.5 (38-52) | 52.5 (42-58) | 48.5 (34-60) | 0.0071 |

| Infarct zone | |||||

| Anterior | 15 (55.56) | 33 (47.83) | 69 (40.83) | 53 (56.38) | 0.0824 |

| Inferior | 12 (44.44) | 36 (52.17) | 68 (40.24) | 26 (27.66) | 0.0147 |

| Lateral | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 31 (18.34) | 14 (14.89) | 0.0002 |

ACOMI: acute coronary occlusion myocardial infarction.

Among patients initially classified as STEMI, 28.12% showed ACOMI. Reperfusion therapy was administered to 88.54% of STEMI patients, mainly by pharmacoinvasive strategy (in 88.5% of the study sample). Among patients initially classified as NSTEMI, 65.64% showed ACOMI. Among them, the angiography findings were LAD disease in 40.8%, RCA disease in 36.6%, and LCx disease in 22.4%; an initial TIMI 0-1 flow was noted in 23.1% in LAD cases, 29.0% RCA cases and 3.0% in LCx cases.

ECG analysis by expert human readers

Human ECG experts diagnosed ACOMI using the current ST-elevation criteria in 60.0% of the sample; a true positive was seen in 71.4% of those with STEMI and 33.3% in those with NSTEMI, with a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 60.0% in those initially classified as STEMI and a sensitivity and specificity of 5.8% and 80.0% in patients initially classified as NSTEMI.

Using non-restricted criteria and their best experience, human ECG experts diagnosed ACOMI in 41.1% of the sample; with 55.5% true positives in those with STEMI and 25.0% true positives in those with NSTEMI, with an overall sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 20.0% in those initially classified as STEMI and a sensitivity and specificity of 12.5% and 40.0% in patients initially classified as NSTEMI.

Human observers showed an overall sensitivity of 33.3% and specificity of 33.3% for the diagnosis of ACOMI when using unrestricted criteria (irrespective of the initial STEMI/NSTEMI presentation) – correctly classifying the 33.3% of the study sample, and showing a sensitivity of 22.7% and specificity of 66.6% for the diagnosis of ACOMI when using STEMI criteria (irrespective of the initial presentation) – classifying correctly the 45.9% of the study sample.

AI model–ECG analysis

The ECG based-AI model diagnosed ACOMI in 84.6% of the sample, with a true positive rate of 100% in those with STEMI and 80.9% in those with NSTEMI, with a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 20.0% in those initially classified as STEMI, and a sensitivity and specificity of 100% and 60.0% in patients initially classified as NSTEMI. Overall, the AI model showed an overall sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 73.3%, correctly classifying 89.1% of the study sample.

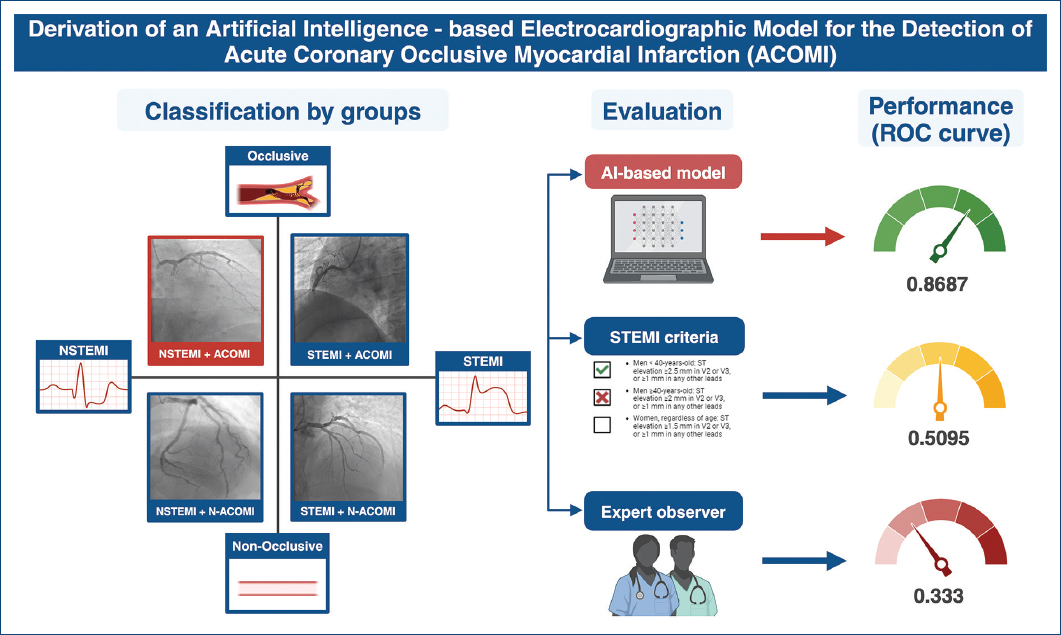

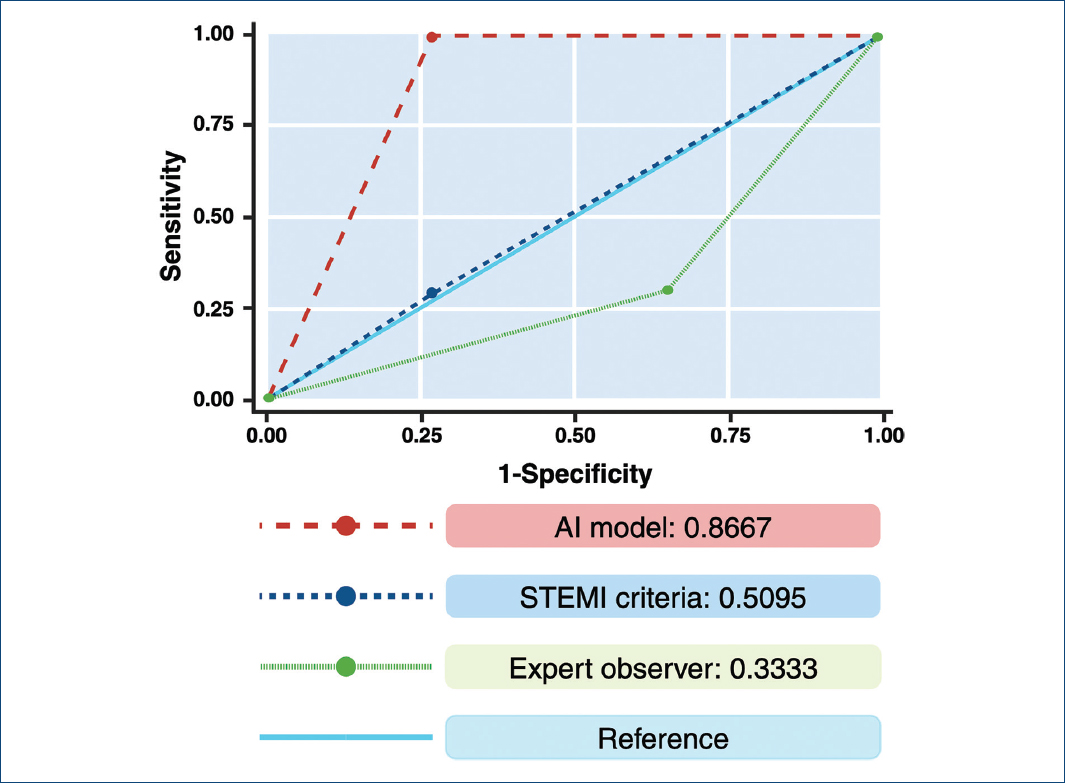

For the primary objective of the study, AI outperformed human experts in both NSTEMI and STEMI, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.86 (95% CI 0.75-0.98) for identifying ACOMI, compared with ECG experts using their experience (AUC: 0.33, 95% CI 0.17-0.49) or under universal STEMI criteria (AUC: 0.50, 95% CI 0.35-0.54), (p value for AUC ROC comparison < 0.001) (Figs. 2 and 3). The AI model demonstrated a PPV of 0.84 and an NPV of 1.0. Table 2 depicts the sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of the ECG AI model and STEMI and Expert's criteria.

Figure 2 Patient selection, study characteristics and results of the performance of artificial intelligence-electrocardiogram model, use of ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction criteria and electrocardiogram expert observer.

Figure 3 Receiver operating characteristic curve showing the performance of our AI algorithm, compared to the use of ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction criteria and electrocardiogram expert observer.

Table 2 Comparison of performance of the different models

| Model | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artificial intelligence-electrocardiogram model | 1.0 | 0.733 | 0.846 | 1.0 | 0.8667 |

| Human expert using ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction criteria | 0.272 | 0.733 | 0.6 | 0.592 | 0.509 |

| Human expert using unrestricted criteria | 0.333 | 0.333 | 0.411 | 0.736 | 0.333 |

Discussion

In the present study, an ECG-based AI model showed promising results for the detection of ACOMI in patients with both STEMI & NSTEMI, exceeding the diagnostic precision of current STEMI criteria and also the opinion of expert observers (trained cardiologists).

ACOMI is an often underlooked entity that has been shown to be associated with increased healthcare resource utilization and worse clinical outcomes in patients with NSTEMI9. While ECG is paramount in the current classification of patients with ACS, it is important to recognize that between 6% and 30% of patients are currently misdiagnosed for what is the pathophysiological substrate that may prompt this classification6: this is, the presence of ACOMI.

Relying solely on the STEMI criteria applied to a standard 12-lead ECG may overlook a considerable number of patients with ACOMI5. Hence, it is crucial to meticulously scrutinize the ECG for subtle alterations that could indicate initial signs of coronary occlusion. It is well established that ECG findings in NSTEMI are not always grossly evident and often require novel identification methods11. Since vessel occlusion is a dynamic process, serial ECG testing might improve the detection of missed events where patients might switch to a higher-risk category in the following hours.

Previous efforts have been made in the present field. In a seminal work, Meyers et al.9 performed a retrospective case–control study of patients with suspected ACS, defining OMI as either (1) acute TIMI 0-2 flow culprit or (2) TIMI 3 flow culprit with peak troponin T 1.0 ng/mL or I 10.0 ng/mL. Their study aimed to compare the accuracy of ECG interpretation using STEMI criteria versus predefined OMI ECG findings. The data utilized belongs to the DOMI ARIGATO database (a two-site collaboration between the Stony Brook University Hospital and Hennepin County Medical Center) and 808 patients were included, of whom 49% had AMI (33% OMI; 16% NOMI). There were 265 OMIs and 131 NOMIs. Sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of STEMI criteria versus OMI ECG findings (Interpreter 1) among 808 patients were 41% versus 86%, 94% versus 91%, and 77% versus 89%, and among 250 patients (Interpreter 2) were 36% versus 80%, 91% versus 92%, and 76% versus 89%, respectively.

Al-Zaiti et al.12 was the first to report the development and external validation of a machine learning model for the ECG diagnosis of OMI in a multicenter cohort study that included 7,313 patients. They compared the AI model against the ECG interpretation of practicing clinicians and the performance of a commercial ECG interpretation system for acute myocardial diagnosis. The model showed an area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) 0.91 (95% CI 0.87-0.96), outperforming both practicing clinicians (AUROC 0.79 (95% CI 0.73-0.76), p< 0.001) and the commercial ECG system (AUROC 0.78 (95% CI 0.70-0.85), p<0.001).

More recently, Meyers et al.10 developed an AI model capable of detecting acute OMI on single-standard 12-lead ECGs and compared its performance with the STEMI criteria. The AI-driven model demonstrated superior performance with an AUC of 0.938 [95% CI: 0.924-0.951] in identifying OMI, with an accuracy of 90.9% (95% CI: 89.7-92.0), sensitivity of 80.6% (95% CI: 76.8-84.0), and specificity of 93.7 (95% CI: 92.6-94.8). In comparison, the use of STEMI criteria showed an accuracy of 83.6% (95% CI: 82.1-85.1), sensitivity of 32.5% (95% CI: 28.4-36.6), and specificity of 97.7% (95% CI: 97.0-98.3). The model showed comparable performance to ECG experts [accuracy 90.8% (95% CI: 89.5-91.9), sensitivity 73.0% (95% CI: 68.7-77.0), and specificity 95.7% (95% CI: 94.7-96.6)].

One of the strengths our model provides is its ability to use cell phone camera input data instead of ECG raw data, making the use of AI accessible for non-specialized healthcare workers, especially in non-tertiary care settings. We avoided using clinical data to enhance its versatile deployment in triage settings. Second, it is real-time use since it can be automated and directly integrated into any smartphone with an Internet connection. This would considerably improve outcomes of patients suffering an ACS in places where an angiography might not be accessible.

However, it is worth remarking that the development of our model is still not ready for clinical use: the image analysis was performed "in batch" (all images simultaneously at the end of the study) with no results deployed in real-time. The research and development pathway for the present initiative comprises the elaboration of a smart-phone based app that allows the clinician to acquire the ECG's photo and perform the ML analysis of the ECG in real time, obtaining results within minutes (due to the time-sensitive nature of the disease), ideally offline (to avoid any connectivity limitation, frequently found in low-resource settings); this technology is in development.

Our study has some limitations we need to take account of. First, we did not include any clinical variable within the model: The addition of clinical variables such as age, sex, vital signs, or personal history (i.e.: diabetes, smoking, etc.) as well as clinical characteristics of the patient's chief complaint could increase the model's precision; this will be included in future iterations. Second, we did not consider any baseline abnormalities present in the ECGs besides ECG analysis for the AI to recognize, so this could have meant an increase of a higher false positive rate; this belongs to a second phase in which an AI-based score incorporating simple clinical characteristics and ECG data will be assessed. Our results also lack generalizability since we used data from a single center. A multi-center use of our algorithm is needed for bigger validation, robustness, and larger sample size. The most important limitation is that the data collected at our center was carefully handpicked to develop our model to maximize its precision to diagnose ACOMI, which could represent an artificial enrichment of our population. Future external validation studies with samples that show a realistic proportion of ACOMI prevalence and are equally distributed are needed.

In addition, our model can only help determine whether an ACOMI is present or not, but it is not capable of detecting a culprit's vessel and does not have an explainability feature, meaning we still cannot fully comprehend what ECG findings could represent an OMI pattern in our algorithm, which could provide insight for experts to start comprehending more about this entity. We didn't aim to explore if the algorithm can affect clinical decisions or meaningful health-care metrics (such as diagnosis to device time, hospital stay, etc.), as all analyses were conducted offline. Prospective validation where OMI probabilities and decision support are provided in real-time is warranted and future studies should aim to evaluate the impact of our algorithm on health-care settings, outcomes, and costs.

Conclusion

In the present study including patients with both NSTEMI and STEMI, an AI-based electrocardiographic model demonstrated a higher diagnostic precision for the detection of ACOMI compared with ECG experts using both STEMI criteria and non-restricted criteria. Further research and external validation are needed to understand the role of AI-based models in the setting of ACS.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)