1 Introduction

1.1 Research Background

Improving healthcare systems has become a strategic priority worldwide. These systems, which encompass a broad range of human and material resources, involve complex interactions among different care groups [1-3]. They are characterized by a high degree of variability and uncertainty, making it challenging to represent and understand their functioning [4-8]. With the continuous increase in the global population and the emergence of new diseases with varying symptoms, as illustrated by the COVID-19 pandemic [9], the demand for healthcare services has significantly risen. This dynamic complicates the tasks of decision-makers and makes the complexity of healthcare systems increasingly evident [10, 13].

Healthcare systems face several complex issues. Patient waiting time management is one of the most pressing problems. Prolonged delays can not only decrease patient satisfaction but also have serious consequences on their health [11]. At the same time, optimizing resource utilization rates is crucial to avoid overloads and inefficiencies that can lead to additional costs and a decline in care quality [1]. Managing patient flows, especially during peak periods, is another major challenge. Poor flow management can result in congestion, extended waiting times, and a decrease in the quality of care [12]. These challenges are exacerbated by the increasing complexity of healthcare systems, requiring effective and rigorous management strategies to ensure their proper functioning and reliability [13].

Modeling and simulation prove to be valuable tools for overcoming these challenges and solving these problems [14]. They help forecast future resource needs, analyze and test different scenarios, identify critical points and bottlenecks, and develop strategies to manage unexpected situations without risking negative impacts in the real world [15-16]. Modeling involves creating a conceptual model of a problem within a system, based on theories or observations [17-19]. This conceptual model must include various essential elements, such as inputs, outputs, content, boundaries, and objectives [20-21]. Once developed, this model is translated into computer software to be simulated under different conditions, allowing healthcare professionals to analyze and better understand the system's behavior in a real-world context [1, 22-24].

1.2 Motivation and Problem Definition

In the field of healthcare, various modeling methods are used to analyze and improve healthcare systems, including:

1) Workflow Methods, which use diagrams to represent processes, information flows, and interactions between different system components [25-29]

2) UML modeling methods, which use various types of diagrams (use case diagrams, sequence diagrams, activity diagrams) to model systems and their interactions [30-32]

3) Agent-based Modeling Methods, which use autonomous agents to simulate individual behaviors and interactions within the system [33-36]; and Petri nets, which are used to represent processes and system resources in graphical form to analyze system flows and behaviors [37-40].

Although these methods are commonly used to address healthcare issues and provide powerful tools for analyzing and improving healthcare systems, they have limitations in terms of formal precision [25-32] and in verifying and managing errors related to the specification of their requirements [25-40]. In this context, using Hoare Logic provides a formal approach to specify and formally verify the requirements of healthcare systems. By integrating formal inference rules, the proposed approach aims to enhance the rigor and reliability of simulations, thereby better managing the complexity of systems and improving their performance.

Hoare Logic [41] is a formal method used for specifying and verifying program properties in a rigorous and mathematical manner. In the context of healthcare, the contribution of Hoare Logic is to provide a formal foundation to ensure that systems adhere to certain essential properties and critical invariants. By integrating Hoare Logic inference rules into the simulation model, this approach is useful for identifying inefficiencies, improving the accuracy of simulation results, ensuring the reliability of operations, and facilitating the decision-making process.

The main contribution of this research paper is to prove how Hoare Logic can be applied to improve healthcare systems performance and support healthcare professionals' decision-making.

1.3 Contribution

The main contributions of our research paper are as follows:

First, we propose a new Hoare Logic based approach by using inference rules specifically adapted for the formal specification and verification of healthcare systems requirements, with a particular focus on the dental department of an Algerian hospital. Our research work is original and makes a significant contribution in health domain by proving the practical application of Hoare Logic and inference rules for the specification, verification, and performance improvement of healthcare systems. Through our proposed case study, we illustrate how the new approach can be used to optimize resource utilization, identify inefficiencies, and minimize patient waiting times while ensuring the reliability and safety of healthcare systems.

Secondly, we propose a simulation Hoare Logic inference rules based-tool to enhance the performance of healthcare systems and support healthcare professionals' decision-making.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews related work on modeling healthcare systems. Section 3 classifies various healthcare systems modeling methods according to their advantages and limitations. Section 4 details the proposed Hoare Logic based-approach, while Section 5 presents the inference rules used to specify and verify healthcare systems requirements. Section 6 is dedicated to the simulation of a case study, with a discussion of the simulation results in Section 7, and a proposal of solutions to improve performance in Section 8. Finally, Section 9 concludes the paper and suggests directions for future research.

2 Related Work

Nowadays, several research works have proposed some methods for modeling and managing healthcare systems to improve these complex systems. However, the choice of modeling methods depends on the specific characteristics of the system and the goals of the modeling.

2.1 Workflow Approach

In [25], the authors developed a workflow model to analyze patient pathways in the pediatric department using real data. This model helps identify bottlenecks and overcrowding situations that contribute to increased service load. They were able to propose improvements to reduce delays and optimize care processes.

In [26], authors built a workflow model to understand and improve the management of patients with uncomplicated sepsis, severe sepsis, and septic shock in an emergency department. Their model contributed to earlier detection and better management of sepsis in the emergency department, thereby speeding up care delivery.

In [27], the authors proposed a workflow model to model the dental center system using data collected in the hospital environment. The accuracy of the model was tested in the real system, contributing to reduced patient waiting times and increased staff productivity.

In [28], the authors proposed an approach to classify and analyze workflow interruptions in the emergency department. The results helped determine the correlations between workflow interruptions and professional stress, enhancing the understanding of the benefits and potential risks of interruptions in emergency work environments.

In [29], the authors constructed a workflow model to design and describe patient flow in the hospital emergency department. Their model contributed to reduced patient waiting times and improved patient flow quality.

2.2 UML-Based Approach

In [30], the authors used UML diagrams to capture key aspects of pediatric care pathways, facilitating comparison across different European Union countries within the Models of Child Health Appraised project. Use case diagrams allowed visualization of activities and actors involved, providing an overview of care processes.

In [31], the authors employed UML models to create various diagrams such as use case diagrams, class diagrams, sequence diagrams, and collaboration diagrams. These diagrams were used to address requirements for regular patient visits, hospitalizations, medication management, and other related tasks. This approach improved visualization and understanding of the complex interactions between different components of the healthcare system, thereby enhancing service efficiency and coordination.

In [32], researchers utilized a UML activity diagram to model the surgical process while developing a probabilistic queuing network model to assess different configurations. This approach enabled the determination of system parameters and conducted simulations to improve surgical processes.

2.3 Agent-Based Modeling Approach

In [33], the authors proposed a medical multi-agent system to enhance coordination and management within healthcare systems. This system uses intelligent agents to manage collaboration between departments, coordination among medical staff, scheduling of medical diagnoses, and patient information collection. By integrating these capabilities, the system developed by the authors aims to improve the quality of patient care by optimizing organizational processes and facilitating more effective management of resources and information.

In [34], the authors proposed an agent-based simulation tool to evaluate rapid treatments in emergency services. The study compares static processes, which use fixed durations for daily operations, and dynamic processes, which adapt treatment based on current conditions in the service. The results provide valuable insights for implementing rapid treatment to reduce patient waiting times in emergency departments.

In [35], the authors developed an agent-based method to model emergency services even with incomplete data. Their approach demonstrates the flexibility and effectiveness of multi-agent systems in managing complexities and uncertainties within emergency services.

In [36], the authors developed an agent-based modeling framework to simulate the behavior of patients leaving an emergency department of a public hospital without being seen by a doctor. The study used cellular automata and agent-based modeling to evaluate the impact of four preventive policies. After applying these policies, an average reduction of 42.14% in the number of patients leaving without being seen and a 6.05% reduction in patient length of stay were observed, with the most effective policy being the rapid treatment of less critical patients. This approach provides a flexible tool for decision-makers to assess the relative impact of control strategies in emergency departments.

2.4 Petri Net Modeling Approach

In [37], the author focuses on analyzing and improving the performance of emergency departments using a model based on hierarchical timed colored Petri nets. The study aims to enhance key performance indicators such as patient waiting times, length of stay, and resource utilization rates. By using historical data to validate the model, several improvement scenarios were tested, demonstrating potential reductions in waiting times and lengths of stay. The most promising scenarios were identified based on their effectiveness and cost.

In [38], the authors use a colored Petri net to model an emergency department. The main objective of this study is to reduce patient waiting times and, consequently, their length of stay in the service. Through simulations of various improvement scenarios, they identify effective strategies to optimize service performance.

In [39], the authors explore the improvement of patient treatment processes in cardiac clinics during the COVID-19 pandemic using timed colored Petri nets (TCPNs). The study aims to optimize patient waiting times and prepare hospitals to better manage the challenges posed by the pandemic. The authors simulated current clinic processes, identified bottlenecks, and proposed optimization scenarios. Their approach demonstrates how TCPNs can be applied to enhance workflows during a crisis.

In [40], the authors address the management of emergency departments (EDs) with a focus on reducing patient waiting and stay times. The study proposes an approach combining modeling and optimization to improve resource utilization. The authors used a colored Petri net to model the system and genetic algorithms to determine the optimal number of resources needed. Simulations provided several models, each contributing to reducing both the length of stay and the time from door to physician.

3 Comparison of Different Modeling Approaches Used in Healthcare

Table 1 below presents a classification of healthcare system modeling methods according to their advantages and limitations.

Table 1 Classification of Healthcare System Modeling Methods Based on Their Advantages and Limitations

| Authors | Service | Methods Used | Advantage | Limitations |

| [25] | Pediatric Department | Workflow Modeling | — Workflow Modeling method provides intuitive visualization and helps identify bottlenecks in processes. — It allows for improvements to optimize processes and reduce waiting times. |

— The simplicity of this method makes it difficult to model complex or nonlinear processes. — Itis less suited for dynamic systems and lack formal mechanisms to verify process compliance, which can affect accuracy and reliability. |

| [26] | Emergency Department | |||

| [27] | Dental Center | |||

| [28] | Emergency Department | |||

| [29] | Emergency Department | |||

| [30] | Child Health Project | UML Modeling | — -UML provides standardization and flexibility to model various aspects of the care system with different types of diagrams, facilitating visualization and understanding of interactions between components. | — UML does not provide a formal framework for verifying system requirements and invariants, which may compromise the rigor and accuracy of modeling. |

| [31] | Visit and Hospital Management | |||

| [32] | Elective Surgery | |||

| [33] | General Hospital Organization | Agent-Based Modeling | — Agent-Based method allows simulation of autonomous and interactive behaviors of agents, offering great adaptability to dynamic and complex systems. — It helps manage complex interactions between different system elements. |

— Implementation of these models can become very complex, requiring significant computational resources to simulate a large number of agents. — It may lack formal rigor to ensure treatment scenarios meet all theoretical specifications. |

| [34] | Emergency Department | |||

| [35] | Emergency Department | |||

| [36] | Emergency Department | |||

| [37] | Emergency Department | Colored Petri Net Modeling | — Petri net method provides a robust approach for modeling healthcare systems, allowing thorough performance analysis and effective resource management. — It is effective for identifying bottlenecks and testing various improvement scenarios. |

— It presents challenges in terms of complexity and requires significant resources for modeling and simulation. — Its adaptability can be limited when dealing with large-scale or highly dynamic systems. |

| [38] | Emergency Department | |||

| [39] | Cardiac Clinics | |||

| [40] | Emergency Department |

4 Our proposed Hoare Logic based-Approach

In this paper, we propose a new formal approach based on tailored inference rules from Hoare logic, specifically adapted for the formal specification and verification of healthcare systems, with a particular focus on the dental department of an Algerian hospital. This approach aims to provide formal precision in defining and verifying expected behaviours, enhance the ability to detect errors through formal analysis, rigorously verify specifications, and thoroughly validate treatment scenarios to ensure their compliance with specific requirements.

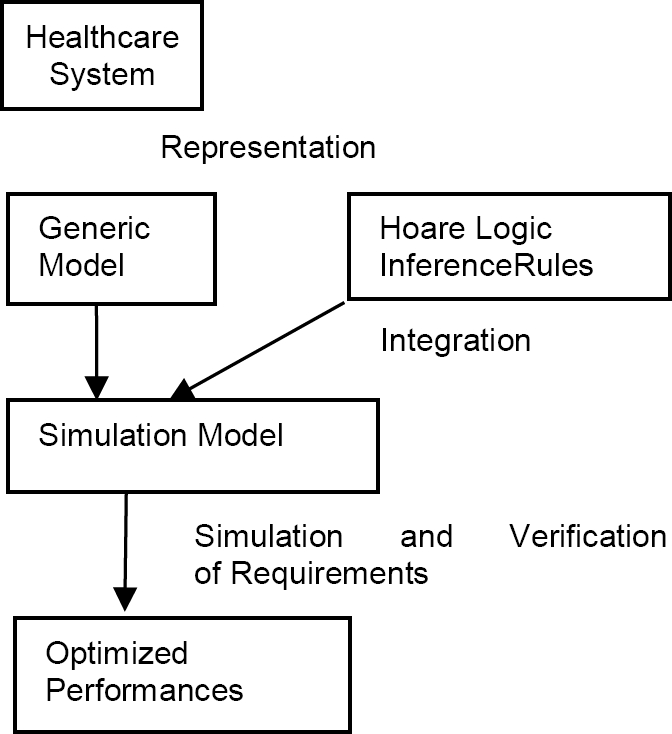

The adopted approach follows a two-step process as illustrated in Fig. 1. The first step involves representing the system in the form of a generic model, and the second step implements this model enriched with specific Hoare Logic inference rules by using a simulation model to verify the healthcare system requirements and improve its performance under real conditions.

4.1 Generic Model

The proposed model is based on three generic elements: the patient entity, the resource entity, and the treatment entity, which are interconnected through interactions. Each element is described by various attributes, and specific functions are also provided to manage each entity.

— Patient Entity: This entity defines the inputs into the healthcare system. Each patient is characterized by: identification, name, arrival time, number of treatment operations, and sequence of treatments. The patient entity is equipped with a function to check the availability of resources and a patient waiting function if the required resource is occupied.

— Resource Entity: This entity defines the set of physical means within the system, such as doctors, nurses, secretaries, operating rooms, etc. Each resource is described by identification, name, resource type (human or material), operational status, and a minimum and maximum preparation time. The resource entity is equipped with a function to occupy the resources needed for patient treatment and a function to release resources.

— Treatment Entity: This entity encompasses all the elementary operations related to treatments. Each treatment is described by identification, the identification of the resource involved in the treatment, treatment name, and minimum and maximum treatment time. The treatment entity is equipped with two functions: start and end of the treatment.

A hierarchical organization is adopted to allow communication between entities of the same level. Thus, the elements—patient, resource, and treatment—exchange information about the patient's treatment on the resources: each patient Pi undergoes one or more operations Tj; each resource Rk handles one or more operations Tj, and each operation Tj is handled by a single resource.

4.2 Simulation and Verification Process for Healthcare Systems

The proposed approach integrates Hoare Logic inference rules into the simulation model to specify and verify the properties of healthcare systems. The simulation and verification process is structured around the following steps:

First, the resources are initialized and prepared for use. Then, patients are managed according to the specified sequence of treatments upon their arrival. At time t, patient Pi arrives and checks the availability of resource Rj for the first operation T1. If resource Rj is occupied, patient Pi waits in the queue; otherwise, they begin the treatment. The patient then proceeds to operation T2, and so on until all operations are completed.

System properties such as the waiting time for each patient, overall simulation time, resource utilization rates, and resource inefficiency times are calculated throughout the simulation. The proposed inference rules are applied to detect potential errors, such as excessive waiting times, high utilization rates, and resource inactivity overruns, and to suggest adjustments aimed at improving system efficiency.

This process has been implemented through the development of a simulation tool that integrates the generic model, the proposed inference rules, and the simulation principles to enhance healthcare system performance and support healthcare professionals in their decision-making.

5 Hoare Logic Inference Rules for Specifying and Verifying Healthcare System Requirements

We propose integrating inference rules inspired by Hoare logic into the simulation model, specifically tailored for the formal specification and verification of healthcare system requirements. These rules aim to enhance resource utilization, reduce waiting times, and ensure the reliability and safety of care.

5.1 Hoare Logic

Hoare logic, sometimes called Floyd-Hoare logic, is a formal method defined by Tony Hoare in [41], is a formal method used for the specification, verification, and proof of computer programs. Its key concepts include Hoare triples, invariant predicates, and inference rules. Although Hoare logic was primarily developed for programming, it can be adapted and extended to be relevant in the specification and verification of complex systems.

A Hoare triple, of the form {P} C {Q}, describes a command C in relation to a precondition {P} (the state of the system before executing C) and a post-condition {Q} (the state of the system after executing C). These Hoare triples are relevant for the specification and verification of complex system requirements because they allow for the formal specification of conditions before and after the execution of an action. This can be used to describe system states, state transitions, and desired properties.

Invariant predicates, denoted {I}, represent properties that must remain constant throughout the execution of a simulation program. They are essential for modeling complex systems as they help ensure that certain important properties are maintained throughout execution, which is crucial for the stability and safety of complex systems.

Inference rules enable the proof of Hoare triples' validity by deriving them from other triples, thereby ensuring a rigorous verification of specifications.

Table 2 presents the list of elements of the healthcare system model, their attributes, and the abbreviations used in our work.

Table 2 The List of Healthcare System Model Elements with Their Attributes and Abbreviations

| System Elements | Patient, Resource, Treatment |

| Functions | -P.Time: represents the time of treatment for patient P. - P.State: (arrived, waiting, in progress, completed) represents the state of the patient. - R.State: (free, occupied) represents the state of the resource R. - R.Time: represents the processing time of resource R. - R.inactive: represents the inactivity time of resource R. - R.File: represents the queue for resource. - T(P, R). (true/false): indicates if there is a treatment of patient P in resource R. - T(P, R).Time_max: represents the maximum treatment time for patient P in resource R. - R.Time_prep_max: represents the maximum preparation time for resource R. - R.rate: represents the occupation rate of resource. |

| Abbreviations | Pi: represents the patient Pi Ti: represents the treatment Ti Ri: represents the resource Ri |

In the following three subsections, we will present the adapted inference rules designed to optimize resource utilization and minimize patient waiting times to ensure the reliability and safety of healthcare systems. Each assertion of these rules is crafted to verify a specific property before and after significant operations, such as patient intake or diagnostics. The pre-conditions and post-conditions defined in these assertions ensure that specified requirements are met, including patient waiting times, resource utilization rates, and inactivity periods, throughout the simulation. If a violation of an assertion occurs, a precise error message is generated to indicate the property that has not been satisfied.

5.2 Inference Rules for Verifying Patient Waiting Time

The waiting times for each patient are calculated to ensure adherence with the maximum constraint. Controlling patient waiting times is essential for improving overall system efficiency and ensuring a continuous flow without bottlenecks. The verification of patient waiting time is based on an inference rule composed of three assertion triplets: Assert 1, Assert 2, and Assert 3. The post-condition of the first triplet (Assert 1) serves as the pre-condition for the second triplet (Assert 2), while the post-condition of the second triplet (Assert 2) becomes the pre-condition for the third triplet (Assert 3). This rule formally specifies and verifies the treatment steps of a patient Pi, with a particular focus on respecting the maximum waiting time constraint, as detailed below.

Assert1: This assertion specifies the first step where Patient Pi arrives and finds Resource Rw occupied. At time V1, Patient Pi arrives with an initial waiting time V2 to receive Treatment Tk on Resource Rw. However, Patient Pi discovers that Resource Rw is currently occupied by Patient Pj. Consequently, from time V4 onward, Patient Pi begins to wait in the queue for Resource Rw:

Assert 2: This assertion specifies the second step where Patient Pi is waiting for Resource Rw to be released. At time V5, Patient Pj completes Treatment Tk on Resource Rw and releases the resource.

Assert 3: This assertion specifies the third step where Patient Pi begins treatment after waiting. At time V6, Patient Pi starts Treatment Tk on Resource Rw, following a cumulative waiting time of V7.

Applicability Conditions: The conditions (1,2,3) detail the necessary calculations within the three assertions (Assert 1, Assert 2, Assert 3) to verify that the maximum waiting time for Patient Pi is respected.

The new waiting time V7 for Patient Pi is calculated as follows: V7 = V2 - (V5 − V4) + the maximum preparation time of Resource Rw, where V2 represents the previous waiting time for Patient Pi, V5 denotes the completion time of Patient Pj’s treatment, and V4 marks the time when Patient Pi began waiting in the queue for Resource Rw. The cumulative waiting time V7 for Patient Pi must not exceed the maximum permissible waiting time. If the assertions are violated, a specific error message will be generated to indicate that the waiting time for Patient Pi has not been respected.

5.3 Inference Rules for Verifying Resource Utilization Rate

The utilization rate of each resource is measured to identify underutilized or overloaded resources. The verification of resource utilization relies on an inference rule composed of two triple assertions: Assert 4 and Assert 5. The post-condition of the first triplet (Assert 4) serves as the pre-condition for the second triplet (Assert 5). This rule formally specifies and verifies the treatment step of a patient Pi, with a particular focus on ensuring compliance with the utilization rate of Resource Rw, as follows:

Assert 4: This assertion specifies the first step where patient Pi begins their treatment after his arrival or waiting. At time V3, patient Pi starts treatment Tk on resource Rw, with an initial treatment time of V2.

Assert 5: This assertion specifies the second step where patient Pi completes their treatment on resource Rw. At time V5, patient Pi finishes treatment Tk on resource Rw, and the new cumulative treatment time for resource Rw becomes V4:

Applicability Conditions: The conditions (4,5, 6,7,8) detail the necessary calculations in the two assertions (Assert 4 and Assert 5) to verify that the maximum utilization rate for resource Rw is maintained.

— The occupancy rate of resource Rw is calculated as follows: Occupancy Rate= V4/V5.where V4 is the new cumulative processing time of resource Rw and V5 is the simulation time or the end time of patient Pj's treatment on resource Rw.

-

— The new processing time of resource Rw (V4) is calculated as:

-

— The end time of patient Pj's treatment on resource Rw (V5) is calculated as:

-

— The start time of patient Pi’s treatment on resource Rw (V3) is calculated as:

— The cumulative occupancy rate of resource Rw must not exceed the maximum allowed rate. In case of any assertion violations, a precise error message is generated to indicate that the occupancy rate of resource Rw is not being respected.

5.4 Inference Rules for Verifying Resource Idle Times

The periods during which resources are not in use are measured to assess and reduce inefficiencies. Monitoring the periods when resources are unused or waiting is based on an inference rule composed of two triples: Assert 6 and Assert 7.

The post-condition of the first triplet (Assert 6) serves as the pre-condition for the second triplet (Assert 7).

This rule formally specifies and verifies the treatment scenario of a patient Pi, with a particular focus on ensuring the idle time of resource Rw is respected as follows.

Assert 6: This assertion specifies the first step where the first patient Pi completes their treatment Tk on the resource Rw at time V2:

Assert 7: This assertion specifies the second step where the next patient Pj begins their treatment after arrival or waiting. At time V4, the next patient Pj (after patient Pi) starts their treatment Tk on the resource Rw, with their cumulative inactive time being V5:

Applicability Conditions: The conditions (9), (10), and (11) detail the necessary calculations in the two assertions (Assert 6 and Assert 7) to verify that that the inactivity time for the resource Rw is respected:

— The inactivity time of resource Rw (V5) is calculated as follows: V5 = V4 - V2, where V4 is the start time of patient Pj's treatment on resource Rw, and V2 is the end time of patient Pi's treatment on resource Rw.

— The start time of patient Pj's treatment on resource Rw (V4) is calculated as follows: V4 = V3 + Maximum preparation time of resource Rw, where V3 represents the time when resource Rw becomes available, meaning the moment when the resource becomes available and patient Pj is waiting. If patient Pj arrives after the availability of resource Rw, then V3 corresponds to the arrival time of patient Pj.

— The cumulative inactivity time of resource Rw (V5) must not exceed the maximum allowed inactivity time. In case of a violation of the assertions, a precise error message is generated to indicate that the occupation rate of resource Rw is not respected.

6 Application: A Case Study

6.1 Presentation of the Dental Department of an Algerian hospital

The healthcare system under consideration is the dental department located in a hospital situated in western Algeria. This department holds a significant position within the hospital. Dental medicine is a medical-surgical specialty that diagnoses and treats conditions of the oral cavity and the maxillofacial regions.

6.2 Data Model of the Dental Department

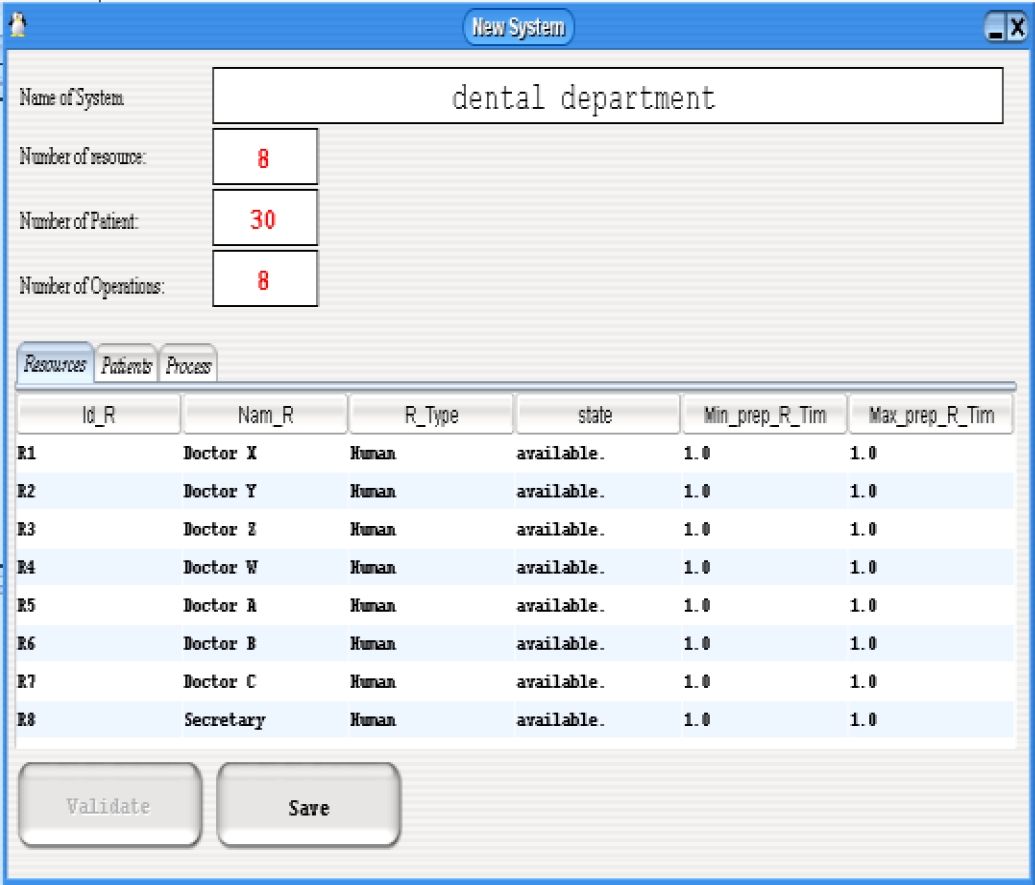

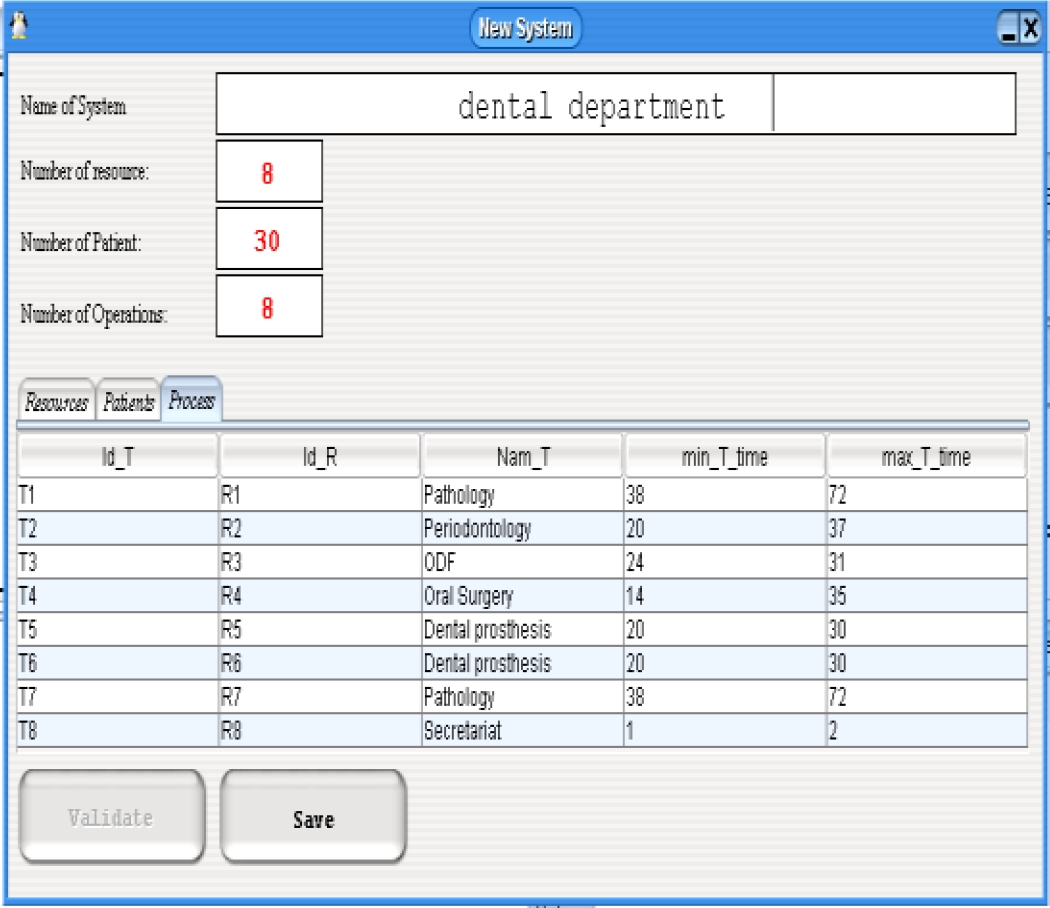

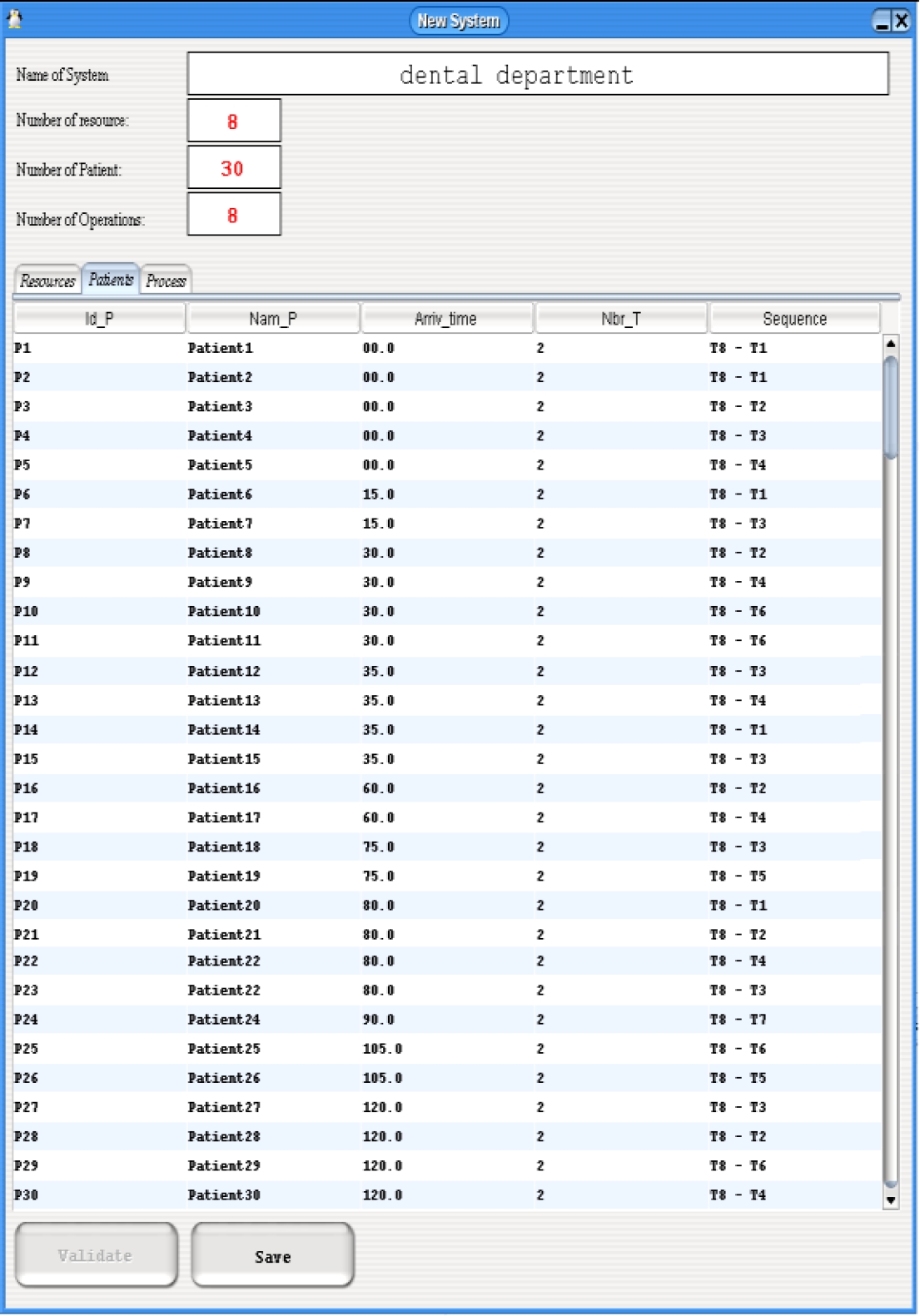

In the context of the generic model, the Patient entity includes 30 patients labeled P1 to P30, and the Resource entity includes 8 resources R1 to R8 corresponding to 7 doctors and 1 secretary. The Treatment entity includes all 8 treatments T1 to T8, representing the 5 specific operations of the dental department along with the secretarial function. These operations are Pathology (performed by 2 different doctors), Periodontology, Dentofacial Orthopaedics (ODF), Oral surgery, and Dental Prosthetics (performed by 2 different doctors).

The complete information about the department's resources (Fig. 2) includes the identifier (Id_Ri), name, type (human), resource status (free), and minimum and maximum preparation times. This time is set to 1 time unit (TU) for all resources. The detailed characteristics of the resources are modeled to simulate the healthcare system realistically. Resource constraints include a resource treatment rate not exceeding 95% and a maximum resource inefficiency time of 35 time units.

Similarly, the eight treatments (Fig. 3) exchange information with the resources, including the treatment identification (Id_T) and the identification of the concerned resource (Id_R), the name of the treatment, as well as the minimum and maximum processing times.

According to the principle of communication between entities, the 30 patients (Fig. 4) exchange treatment information, such as the patient's arrival time, the number of operations performed for the patient's treatment, and the corresponding treatment sequence. For example, patient P1 undergoes treatments T8 and T1, according to the relevant operations. The patient constraint includes a maximum waiting time of 100 time units.

All patients are initially processed through operation T8, as they first interact with the secretary (resource R8), who handles their files. They are then attended to by a doctor (resources R1 to R7) who will perform a treatment Ti (i=1 to 8, with i ≠ 8) based on the type of care required. For example, patient P1 undergoes a pathology treatment (T8-T1), while patient P3 undergoes a periodontology treatment (T8-T2).

7 Results and Interpretations

The simulation stopped at 367 time units. The last patient started their treatment at 295 time units.

7.1 Performance Relative to Patients

7.1.1. Results

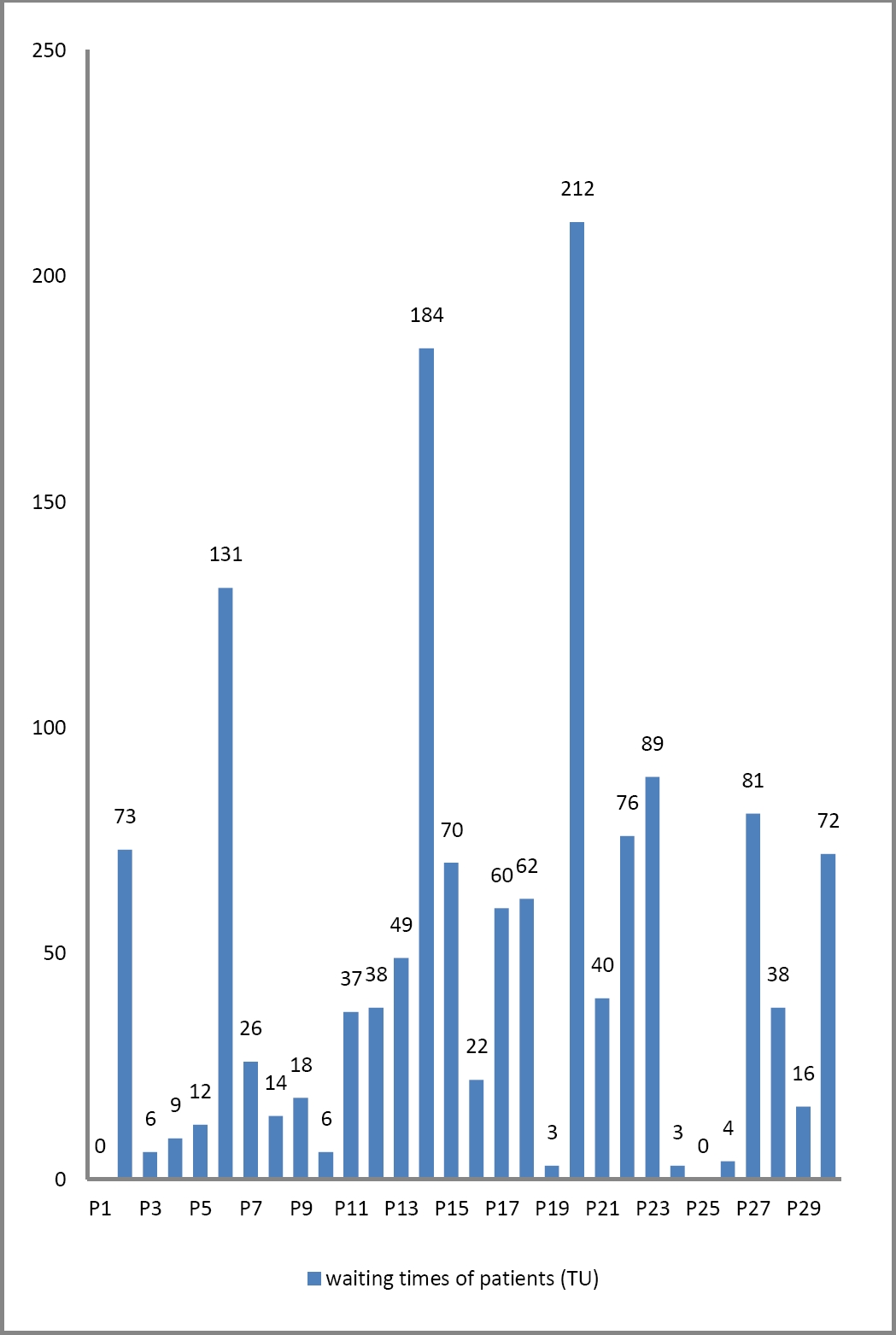

By applying the simulation principle, the evaluation of performance criteria for the 30 patients (Fig. 5) produced the following results concerning the waiting time (in time units) of the patients.

7.1.2. Interpretation

The waiting times for patients range from 0 to 212 time units. The shortest waiting times are for patients (P1, P3, P4, P5, P10, P19, P24, P25, P26), who arrived when the resource assigned to their treatment was available. The longest waiting times are for patients (P6, P14, and P20), who were directed to Resource 1 (Doctor X, a specialist in pathology). This high waiting time is attributed to the extended duration of examinations for this specialty, which is 72 time units.

7.2 Performance Relative to Resources

7.2.1. Results

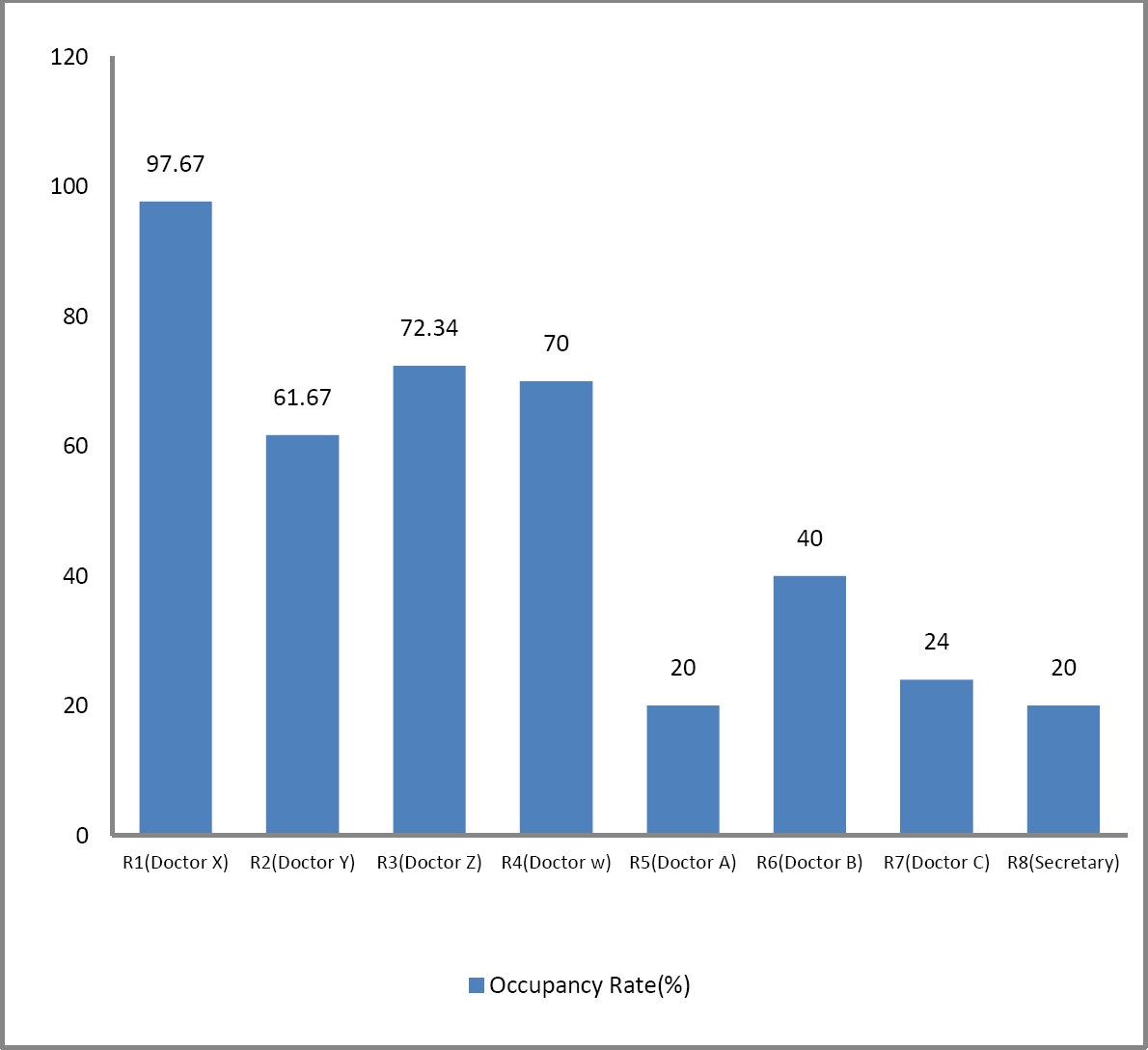

By applying the same simulation principle, the evaluation of the performance of the 8 resources (doctors and secretary) produced the following results (Fig. 6) concerning the utilization rate. The resource utilization rate was calculated at time 300 UT, corresponding to the end of the morning work period.

7.2.2. Interpretation

The reception occupies 20% of the secretary's (resource R8) working time. The utilization rates of the doctors range from 20% to 97.67%.The lowest utilization rates are observed for Doctor A (resource R5), Doctor B (resource R6), and Doctor C (resource R7). These three doctors see a low number of patients (two for Doctor A, four for Doctor B, and one for Doctor C).The highest utilization rate is for Doctor X, a pathology specialist, with 97.67%. This high rate is due to the large number of patients handled by this doctor and the extended duration of examinations for this specialty (72 time units).

7.3 Reported Errors and Suggestions

7.3.1. Errors

The application of the proposed Hoare logic inference rules to verify the requirements of the dental department revealed the following errors:

— At time 35: The inactivity time for resources R5, R6, and R7 has been exceeded.

— At time 60: The utilization rate of resource R1 (Doctor X) exceeds the maximum allowed of 95%.

— At time 118: The waiting time for patient P6 exceeds 100 time units.

— At time 137: The waiting times for patients P6 and P14 exceed 100 time units.

— At time 182: The waiting times for patients P6, P14, and P20 exceed 100 time units.

7.3.2. Interpretation and Suggestions

— At time 35: Resource R7 (Doctor C, a pathology specialist) is not receiving any patients, while resource R1 (Doctor X, also a pathology specialist) has one patient in treatment and two patients waiting (P2 and P6). The treatment duration for this specialty is long (72 time units), which leads to increased waiting times for patients. We suggest redistributing patients between these two specialized resources to balance their utilization, reduce the overload on resource R1, and decrease the waiting times for patients P2, P6, and P14.

— At time 60: Resource R5 (a dental prosthetics specialist) is not receiving any patients, while resource R6 (Doctor B, also specializing in dental prosthetics) has one patient in treatment and one patient waiting (P11). The treatment duration for this specialty is short (30 time units). We suggest directing patients to resource R6 to improve resource utilization and enable resource R5 to be operational, for instance, during the evening period.

8 Proposed Solution

Considering the errors identified during the verification of the dental department's requirements and the proposed suggestions, we have decided to reassign patients P2 and P6 to resource R7. Additionally, patients waiting at resource R5 will be directed to the waiting area of resource R6. This adjustment led to the following results: The simulation stopped at 235 time units.

8.1 Improvement in Work Time Performance

The simulation ended at 235 time units, reflecting a reduction of 132 time units compared to the previous scenario.

8.2 Improvement in Patient Performance

8.2.1. Results

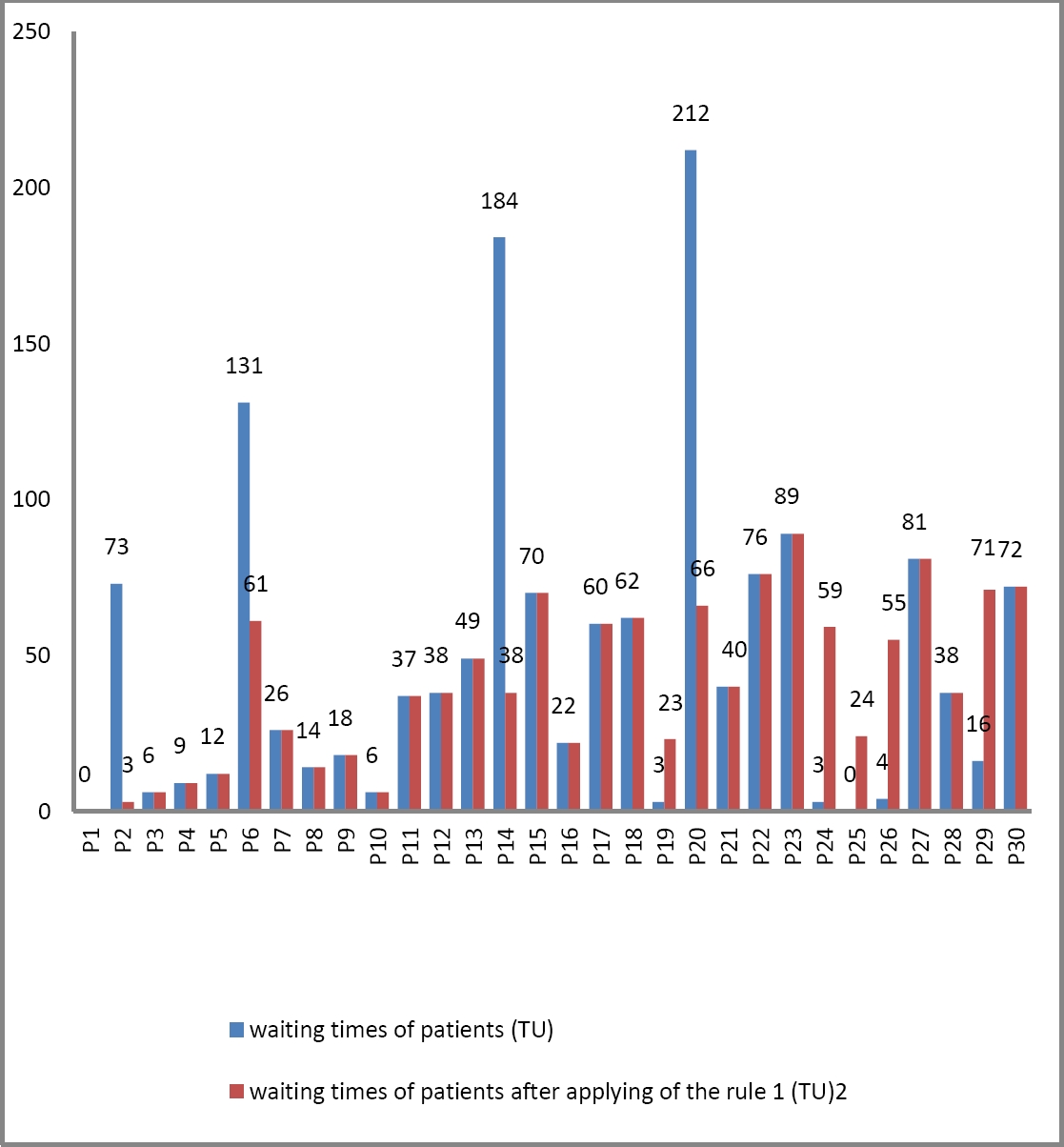

The performance improvements for the 30 patients resulting from the application of our approach are illustrated by the results shown in Fig. 7. These results display the waiting times (in time units) for patients before and after implementing the inference rule detailed in subsection 5.2.

8.2.2. Interpretation

The application of our approach resulted in notable improvements in patient waiting times in the pathology specialty, with significant reductions: 70 time units for patients P2 and P6, and 146 time units for patients P14 and P20. In contrast, the proposed adjustments for resources in the dental prosthetics specialty led to a slight increase in waiting times for some patients. However, this increase remained within reasonable limits, indicating that the adjustments have overall optimized the system while maintaining acceptable waiting times for other specialties.

8.3 Improvement in Resource Performance

8.3.1. Results

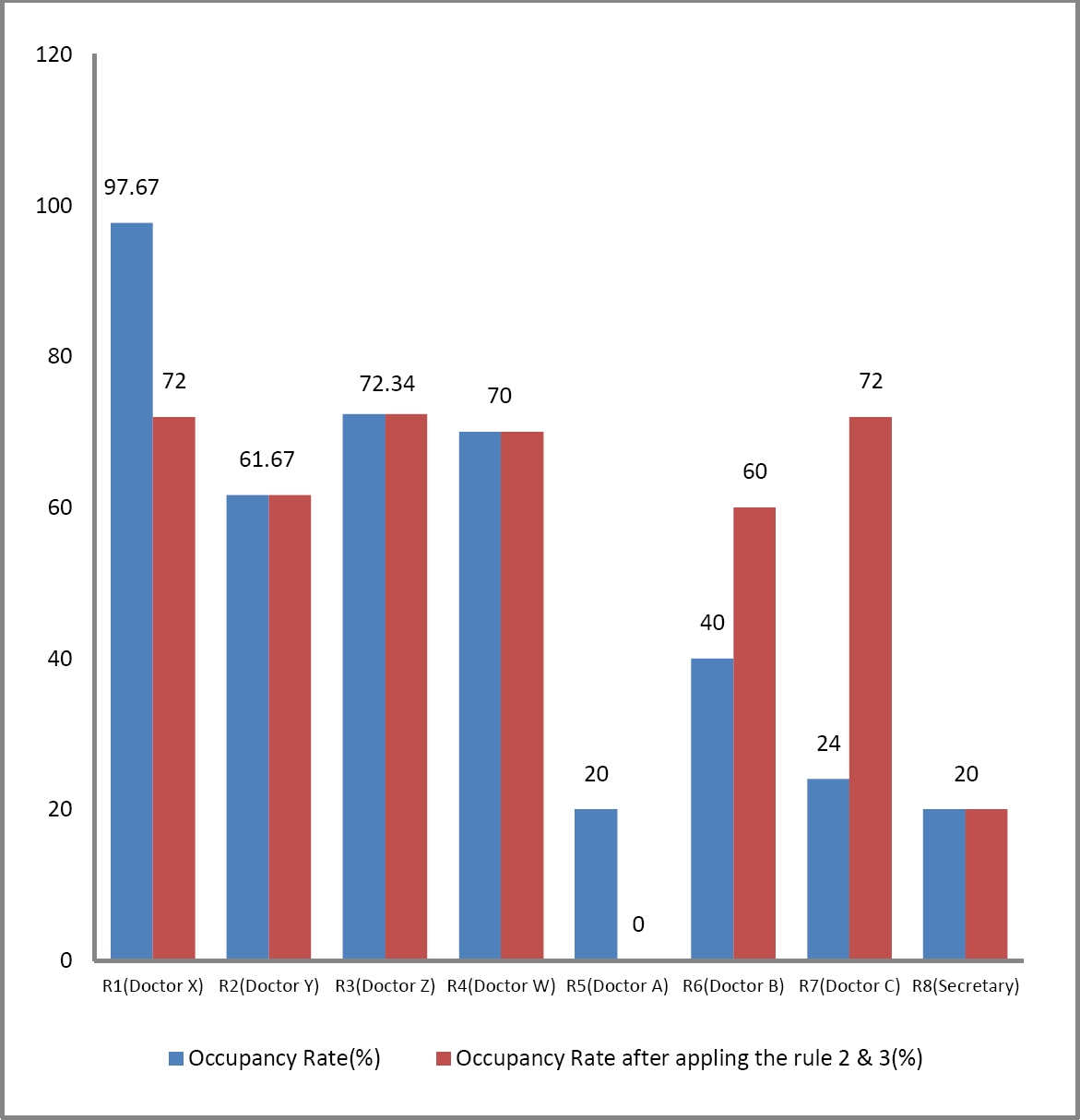

The enhanced performance resulting from the application of our approach for the 8 resources (doctors and secretary) is illustrated by the following results (see Fig. 8). These results show the utilization rates before and after applying the inference rules detailed in subsections 5.3 and 5.4. The resource utilization rates are calculated at time 300 time units, corresponding to the end of the morning work period.

8.3.2. Interpretation

The Improvements in resource performance are notable. The utilization rate for pathology doctors showed significant variations: it decreased by 25.67% for Doctor X, while it increased by 48% for Doctor C. Regarding the dental prosthetics specialty, the number of resources was reduced from two (R5 and R6) to one (R6). This reorganization optimized the use of resource R6, whose utilization rate increased from 40% to 60%. In contrast, the utilization rates of the other resources remained unchanged.

9 Conclusion and Future Work

This research paper proposes a novel approach for improving healthcare systems using Hoare logic inference rules. With its ability to formulate precise and verifiable specifications, Hoare logic facilitates the detection and correction of inefficiencies, enhances resource management, reduces waiting times, and ensures the reliability and safety of care.

We have applied our study to a dental department in an Algerian hospital, demonstrating that it can provide significant improvements in healthcare system performance.

This approach offers a rigorous framework for verification and optimization, contributing to more effective and reliable management of healthcare systems.

For our future work, it would be valuable to apply this approach to other hospital settings and various types of complex systems to offer new insights and further enhancements in performance and reliability.

Another promising avenue would be to explore the integration of Hoare logic with artificial intelligence methods. Combining these approaches could provide more robust, adaptable, and optimized solutions for managing healthcare systems.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)