1. Introduction

The characterization of capable crustal faults for the evaluation of the seismic hazard implies knowledge of their cartographic length, their geometry and location. Thus, precise knowledge of these parameters is necessary for a reliable estimation of expected earthquakes and, consequently, a more reliable hazard analysis (e.g.Audemard and Singer, 1996; Audemard et al., 2000; Oldecop and Perucca, 2012). These parameters are usually evaluated using standard structural geology and geomorphology tools.

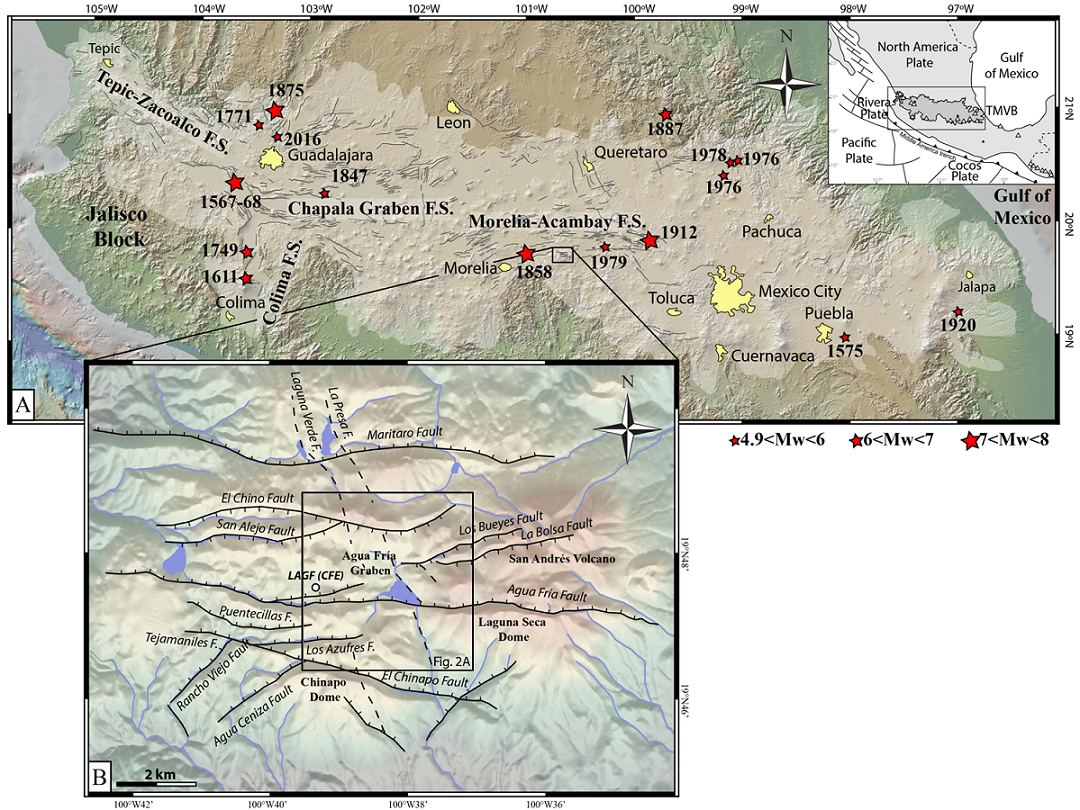

However, in some cases, all or part of the faults may be invisible on the surface due, for example, to high sedimentation or erosion rates (e.g.Nguyen et al., 2007; Pueyo Anchuela et al., 2016; Lacan and Arango-Galván, 2021).Such difficulties in identifying and characterizing the geometry of partly buried active faults are particularly true in the Trans Mexican Volcanic Belt (TMVB), an E-W volcanic arc that crosses central Mexico from the Pacific Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico (Figure 1A). Most of the TMVB is affected by intra-arc extension and is, therefore, cut by several normal fault systems. In the central part of the TMVB, the Morelia-Acambay fault system (MAFS) consists of close to a hundred active E-W to ENE-WSW normal faults, distributed over 200 km between the cities of Morelia and Acambay (Figure 1A; Suter et al., 1992, 1995, 2001; Garduño-Monroy et al., 2009; Mendoza-Ponce et al., 2018; Ortuño et al., 2019).

Figure 1 (A) Seismotectonic and historical seismicity map of the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt (TMVB). Modified from Ferrari et al. (2012); Suárez et al. (2019); Suter (2019); Zúñiga et al. (2020). (B) Structural map of the Los Azufres Volcanic Field. LAGF= Los Azufres Geothermal Field (CFE Power plant).

Historical and instrumental earthquake records provide evidence of activity of at least some faults of the MAFS (Suárez et al., 2019, 2020). The most emblematic historical earthquakes in this area are the 1912 Acambay (Ms 6.9; Urbina and Camacho, 1913; Suter et al., 1995; Langridge et al., 2000), the 1979 Maravatio earthquake (Mw 5.5; Astiz-Delgado, 1980; Rodríguez-Pérez and Zúñiga, 2017) and probably the 1858 St. Juliana earthquake (Figueroa, 1987; Suárez et al., 2019, 2020) . Paleoseismological studies confirmed the Holocene activity of most of the faults of this system, obtaining recurrence intervals for large (M≥6) earthquakes of between 1,000 and 10,000 years along any given fault (Langridge et al., 2000, 2013; Sunyé-Puchol et al., 2015; Ortuño et al., 2015, 2019; Suter, 2016; Lacan et al., 2018; Soria-Caballero et al., 2019). East of the MAFS, there is no geomorphic evidence of active faulting (Figure 1A). Nevertheless, the occurrence of the destructive 1920 Jalapa earthquake (Mw 6.4, Suárez, 1992; Suárez and Novelo-Casanova, 2018), as well as additional seismic events which took place in the eastern TMVB (Suter et al., 1996), represents clear indications that the region is tectonically active and the related seismic hazard has to be evaluated (Zúñiga et al., 2020).

The MAFS defines a succession of grabens and half grabens partially filled with Pleistocene to Holocene sediments (e.g.Martínez-Reyes and Nieto-Samaniego, 1990). In the central part of the MAFS, the Los Azufres volcanic field is crossed by different faults which form the small Agua Fría graben (Dobson and Mahood, 1985; Ferrari et al., 1991; Pradal and Robin, 1994) within which the Los Azufres geothermal power plant is located (LAGF; Figure 1B). This 1 km wide graben represents a good analogous of the larger-scale structures that form the MAFS. In this area, several tectonic structures have been identified based on structural geology and geomorphic studies (e.g.Camacho, 1976; De La Cruz et al., 1983; Ferrari et al., 1991; Pérez-Esquivias et al., 2010). For the past three years, our group has been focusing on the neotectonic study of the Agua Fría fault, the longest of the tectonic structures identified in the Los Azufres volcanic Field, and the evaluation of the related seismic hazard. To do so, detailed structural and geomorphological mapping was carried out along this fault and the northern segment of the Agua Fría fault was identified (Campos Medina, 2018). To specify its location and estimate its extension in the sedimentary filling of the Agua Fría Graben, where the fault does not present any topographical expression, geophysical subsurface prospecting was necessary.

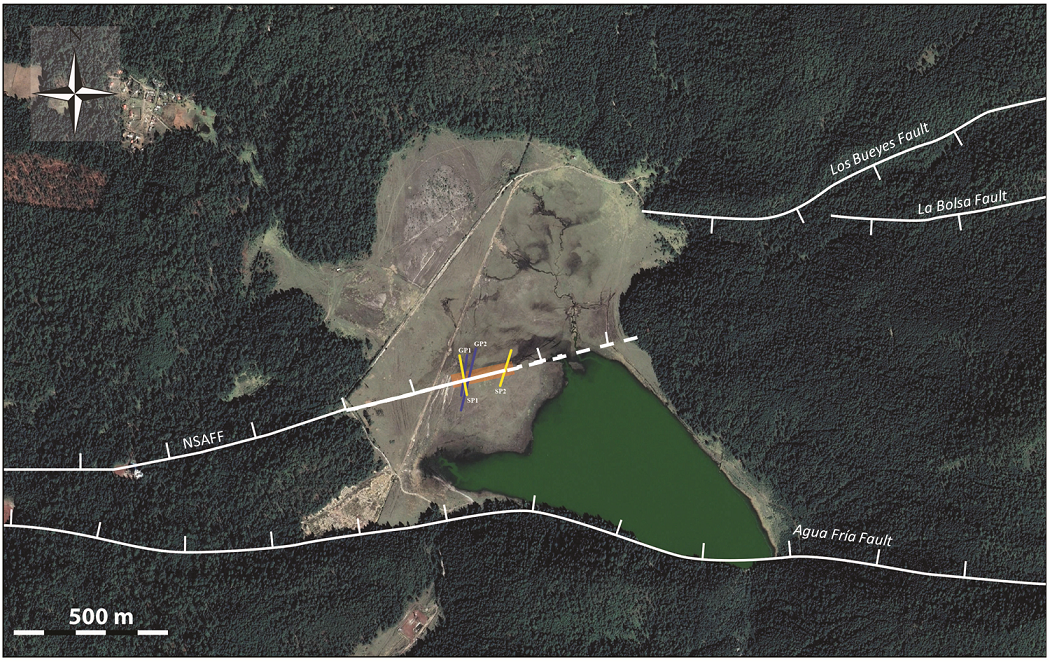

In this context, the main purpose of this work is to identify, locate, and characterize the geometry of the partially blind and potentially active northern segment of the Agua Fría fault. To reach this main goal, a combination of non-invasive geophysical tools such as total magnetic field, ground penetrating radar (GPR), and seismic refraction are used to image a potentially active structure in the Llano Grande Basin (Figure 1B). Preliminary results have been used to identify paleoseismic excavation sites studied by Campos Medina (2018). These new paleoseismic results are used in the discussion of the present study to validate the interpretations of geophysical results.

In detail, the total magnetic field anomaly data are used to detect and map the main structural domains and the potential structural lineaments that separate them. Detailed high-resolution GPR profiles across one of these magnetic lineaments lead to image reflectors offsets and interpret the lineament as a capable fault and locate trenching sites. Furthermore, the seismic refraction allows for the determination of lateral and vertical velocity variations associated with the magnetically identified tectonic structure, and also to image the fault zone at depth.

2. Geological framework

The TMVB is a Late Miocene to Holocene volcanic arc, which crosses Mexico from west to east (Ferrari, 2000 and references inside). It is intersected by several fault systems that have been partially reactivated at different times during its evolution (Ferrari et al., 2012 and references inside). The intra-arc Neogene deformation in the TMVB consists of extensional fault systems delimiting rift valleys, filled by volcanic materials and fluvio-lacustrine sediments (Johnson and Harrison, 1990; Ferrari et al., 2012). In the central part of the TMVB, the E-W active MAFS intersects NNE-SSW to NNW-SSE-trending Basin-and-Range extensional structures (Pasquarè et al., 1988; Ferrari et al., 1991).

The persistent activity of the MAFS has been demonstrated by the occurrence of historical earthquakes (Suárez et al., 2019), structural data (Suter et al., 2001), and paleoseismological studies that additionally characterize their seismogenic potential (Lacan et al., 2018 and references inside).

Unfortunately, only few geophysical studies have been conducted to evaluate the geometry of the faults at depth and their relationships (e.g.Arzate et al., 2018).

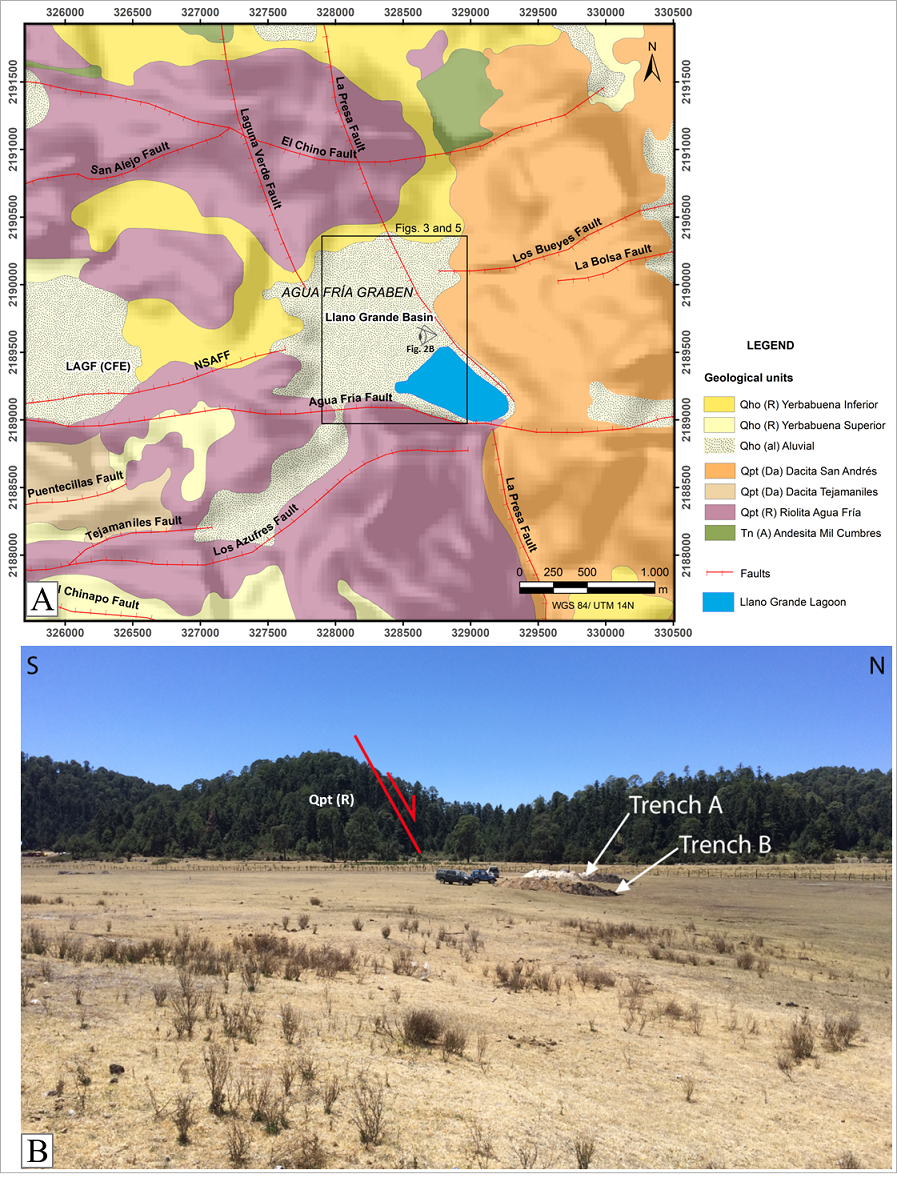

Los Azufres Volcanic Complex (LAVC) in the State of Michoacán is located along and dissected by the MAFS. The E-W faults of the MAFS affect the topography of the volcanic edifice (Arce et al., 2012). Their mapping was set out at different scales for the needs of geothermal studies (Camacho, 1976; Dobson and Mahood, 1985; Ferrari et al., 1991; Pradal and Robin, 1994; Suter et al., 2001). However, their precise mapping and characterization for seismic hazard assessment started with our group three years ago (Campos Medina, 2018). The LAVC covers 676 km2. Its chemical composition is predominantly rhyolitic to dacitic, although some basaltic and andesitic products have been described (e.g.Ferrari et al., 1991; Macías et al.,2008; Figure 2A).

Figure 2 (A) Geological map of the Agua Fría Graben showing the main geological units and fault traces. (B) Picture illustrating the morphological expression of the NSAFF on the rhyolitic basement and in the Llano Grande basin. The location of Campos Medina (2018) trenches A and B is shown. The black box indicates the magnetic studies area. LAGF= Los Azufres Geothermal Field (CFE Power plant), NSAFF= Northern segment of the Agua Fría Fault (modified from De La Cruz et al., 1983 and Campos Medina, 2018).

The study area is a sedimentary basin called Llano Grande. It is located within the LAVC. This zone lies between 100° and 101° W, in the vicinity of LAGF which is 2850 masl. This area is approximately 100 km east of Morelia, within the small Agua Fría graben (Figures 1 and 2). The Agua Fría Graben is bounded by two faults of the MAFS: the Agua Fría fault (to the south) and the El Chino fault (to the north) and define the sedimentary basin of Llano Grande (Figure 2A). Locally, these active faults intersect with the older NNW-SSE Laguna Verde and N-S La Presa faults. These latter have been identified by structural geology and geophysical studies, but show little or no morphological expression (De La Cruz et al., 1983; Dobson and Mahood, 1985; Campos-Enríquez and Garduño-Monroy, 1995; Pérez-Esquivias et al., 2010). The bottom of the Llano Grande basin is partially covered by a dam lake to the south-east. The emerging part of the sedimentary filling (in the northwest) presents a relatively flat surface, chiseled by numerous topographic escarpments, mainly caused by the erosion of torrential streams. In this context, possible micro-topographic signals related to recent faulting are masked by the roughness of the ground (Figure 2B).

3. Methodology

3.1. TOTAL FIELD MAGNETIC DATA

Non-invasive magnetics methods are often appropriate for locating blind structures (e.g.Glen et al.,, 2008). During the last five decades, a variety of methods based on vertical and horizontal gradients of magnetic potential-field anomalies have been developed and implemented for the determination of geologic boundaries, such as lithological contacts and faults, hence these methods are also valuable for the exploration of geothermal resources (Nabighian, 1972, 1974; Keating and Pilkington, 1990; Ferreira et al., 2013; Mazzoldi et al., 2020). At the studied site, a regular mesh was designed to acquire total field magnetic data using a Geometrics G-857 proton-precession magnetometer, connected with 2 m of horizontal resolution Garmin Oregon 450 GPS. Thirteen 1320 m-long N-S oriented profiles (in-lines) and five 1150 m-long orthogonal profiles (cross-lines) were surveyed. The spacing between stations was 25 m on each line (Figure 3), for a total of 583 field magnetic measurements.

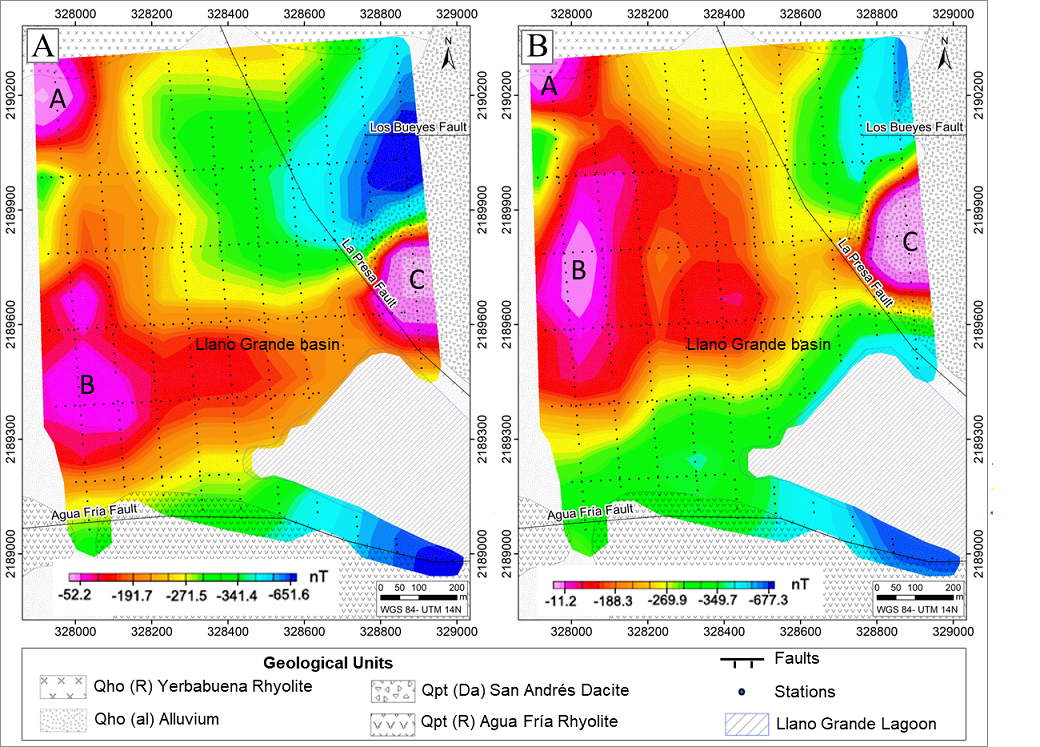

Figure 3 Magnetic anomaly maps of the Llano Grande basin, (A) Residual magnetic field map (RMF map), (B) Reduction to the pole map (RTP map). A, B and C letters inside maps correspond to identified magnetic anomalies.

The total field magnetic data have been corrected for diurnal variations using values of the Magnetic Observatory of Teoloyucan. The regional component of the Earth's Magnetic Field (IGRF) has been removed to obtain the local anomaly.

To generate the final residual magnetic field map (RMF map) we have applied an Upward Continuation (UC) filter, which is essentially low pass in the frequency domain, to filter out the contributions of shallow sources (e.g.Gianiyu et al., 2013; Ferreira et al., 2013). Subsequently, a Reduced-to-Pole (RTP) map has been calculated by applying an RTP filter to the RMF data using a site magnetic Inclination and Declination of 47.27° and 5.22°, respectively. The RTP filter is used to deskew the anomaly, obtaining an anomaly that would have been observed if the Earth's magnetic pole had been located at the measurement site. The processing methodology from Mazzoldi et al. (2020) has been used to obtain the magnetic anomaly. A spectral analysis was carried out on the RMF data to estimate the depths of the source bodies.

For this analysis, the magnetic data were transformed from the spatial domain to the frequency domain using the MAGMAP module of Geosoft's Oasis Montaj software. Several authors (e.g.Garcia and Ness, 1994; Tatiana and Angelo, 1998, among others) explained the spectral analysis technique. It is based on the analysis of the magnetic data using Fourier Transform on the spectral analysis map and its computer conjugate (Araffa et al., 2017).

The horizontal derivative maps in both X and Y directions were generated from the RTP data. These maps emphasize the source effects, reducing the interference effects of the anomalies and yield an enhanced image of the boundaries (e.g.Skrame et al., 2016). For its part, the vertical derivative was mathematically determined from the total field magnetic anomaly map to highlight the locations of faults and contact features. The first vertical derivative represents a sharper resolution of near-surface features (Araffa et al., 2019).

3.2. THE 2D GPR SURVEY

Since the use of GPR is a classical technique to image buried structures, only a short overview of the GPR methodology is presented here. For a more complete description of the basics of GPR see Davis and Annan (1989), Neal (2004), among others. The technique is based on the measurements of the subsurface echoes of the transmitted high-frequency electromagnetic waves (EM; typically 16 MHz-1000 GHz). A transmitting antenna on the ground surface emits EM waves in distinct pulses that propagate into the ground and reflect or diffract at interfaces where the dielectric permittivity of the subsurface changes (Davis and Annan, 1989; Daniels, 2000; Jol and Bristow, 2003). EM wave velocity data allow the conversion of a time record of reflections to an estimated depth record (Gómez-Ortiz et al., 2007).

In paleoseismology, the use of GPR as a tool to detect and analyze the nature and architecture of active or Quaternary fault zones and faults in shallow subsurface is well known (e.g.Demanet et al., 2001; Rashed et al., 2003; Audemard et al., 2006; Christie et al., 2009; Pauselli et al., 2010; Wallace et al., 2010; Lacan et al., 2012; Cinti et al., 2015; Hermana et al., 2019; Gunda et al., 2020). The GPR profiles provide high-resolution images of shallow stratigraphy and subsurface fault zones which lack clear surface expressions. Hence, such profiles facilitate the identification, mapping, and characterization of the area affected by blind tectonic structures (Gunda et al., 2020).

The signal/noise ratio of GPR data is high when the permittivity contrast between the units displaced by the fault is significant because of the abrupt change in the electrical property of the material (Joshi et al., 2012). In the study area, the subsurface consists of intercalations of fluvio-lacustrine and volcanic units which could be represented by visible changes in the pattern of the reflectors. The 2D profiles were surveyed using a MALA GPR instrument equipped with 250 MHz and 100 MHz shielded antennas to achieve results with an ideal balance between penetration depth and vertical resolution. Profile lengths have been measured using an electro-mechanic odometer incorporated in the equipment. Topographic profiling was carried out with a GeoMax ZAL 132 instrument. We applied a basic processing sequence to the measured data, using the Reflex v.3 software (developed by Sandmeier, 2016), with common consistent steps such as drift removal (i.e. zero time correction), dewow filter, bandpass filter, background removal, topographic correction, depth control, etc. (e.g.Malik and Mohanty, 2007; Xavier and Gibson, 2011; Ercoli et al., 2013; Robinson et al., 2013). The average velocity of 0.11 m/ns was calculated using the velocity analysis tool in Reflex.

3.3. SEISMIC REFRACTION

The seismic refraction method is a useful tool to determine depths to subsurface interfaces and the velocities of the layer between them (Lillie, 1999). It illustrates P-wave or S-wave velocity variations of the subsurface and, in turn, this method allows for the interpretation of structural or stratigraphic discontinuities. Also, seismic refraction is commonly used in engineering, mining, groundwater, environmental or geothermal exploration (e.g.Shah et al., 2015; Brixová et al., 2018). Several investigations have also combined seismic refraction with other geophysical techniques (commonly Downhole geophysics, electrical and EM profiling) to recognize active fault zones and precisely locate trenching sites for seismic hazard assessment (e.g.Demanet et al., 2001; Terzic et al., 2017, 2019; Blecha et al., 2018).

The seismic refraction data at the Llano Grande basin have been acquired across the main anomalies identified with the magnetic study. The data were obtained using a GEOMETRICS, 24-channel, GEODE seismometer, with 4.5 Hz vertical geophones spaced 5 m apart. In most of the study, the controlled source used to generate acoustic waves was a 200 kg free-fall seismic source but in some less accessible sites, an 8 kg hammer was used. The source points were placed every 60 m on each 120 m long profile (at 0 m, 60 m, and 120 m). Each seismic section has a maximum recording time of 0.5 s and all seismic records were acquired with a sampling rate of 4,000 samples/s.

The arrivals of each seismic wave generated by the source are detected by the set of geo-phones. For each source point, a seismic section (from SEG-2 data format) was obtained using the Reflex v.3 software. The first arrivals of the seismic wave were picked for each geophone on the seismic section. For each profile, we integrated the arrival times interpreted on the seismic sections.

We established a 2-3 layers initial model for each profile with their respective vertical velocity variations. Free software RAYINVR by Zelt and Smith (1992) was used to perform the forward modeling technique. This technique allows fitting the arrivals times calculated by the model to the first arrivals interpreted in each profile, therefore, a P-wave velocity model was obtained. Such a model was used to identify the P-wave vertical and lateral velocity variations which we relate with structural or lithological variations in the subsurface.

4. Results

4.1. TOTAL FIELD MAGNETIC DATA

The RMF map (Figure 3A) and the RTP map (Figure 3B) show almost the same anomaly distribution with only a slight northward shift of the anomaly B. The magnitude of this anomaly increases both in its areal extent and its vertical relief. In the following, we will focus on describing the results obtained on the RTP map considering its precision in the direct interpretation of the magnetic sources.

The analysis of the RTP magnetic anomaly (Figure 3B) indicates that the magnetic field in the area has a maximum amplitude of about -11 nT to the northwest and the east of the studied area (A, B, and C in Figure 3B) and minimum amplitude of about -670 nT to the south and the northeast. The most important magnetic trends show two main orientations. One, in an ENE-WSW direction, in the central part of the study area, is more or less parallel to the Agua Fría fault and a second, in a NW-SE direction, is parallel to the Laguna Verde fault.

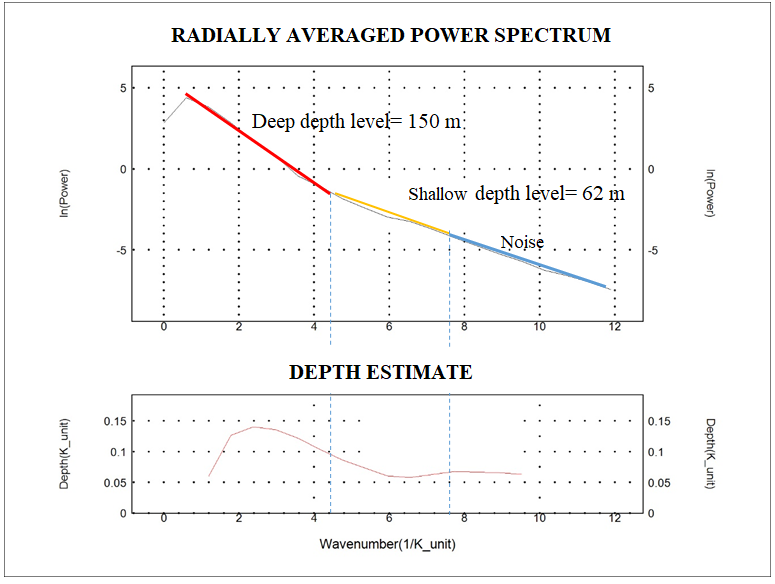

The radially averaged power spectrum (Figure 4) illustrates the estimated average depth levels of magnetic sources prevailing in the study area. This averaged power spectrum indicates that the deeper source is about 150 m and the shallower is about 62 m depth.

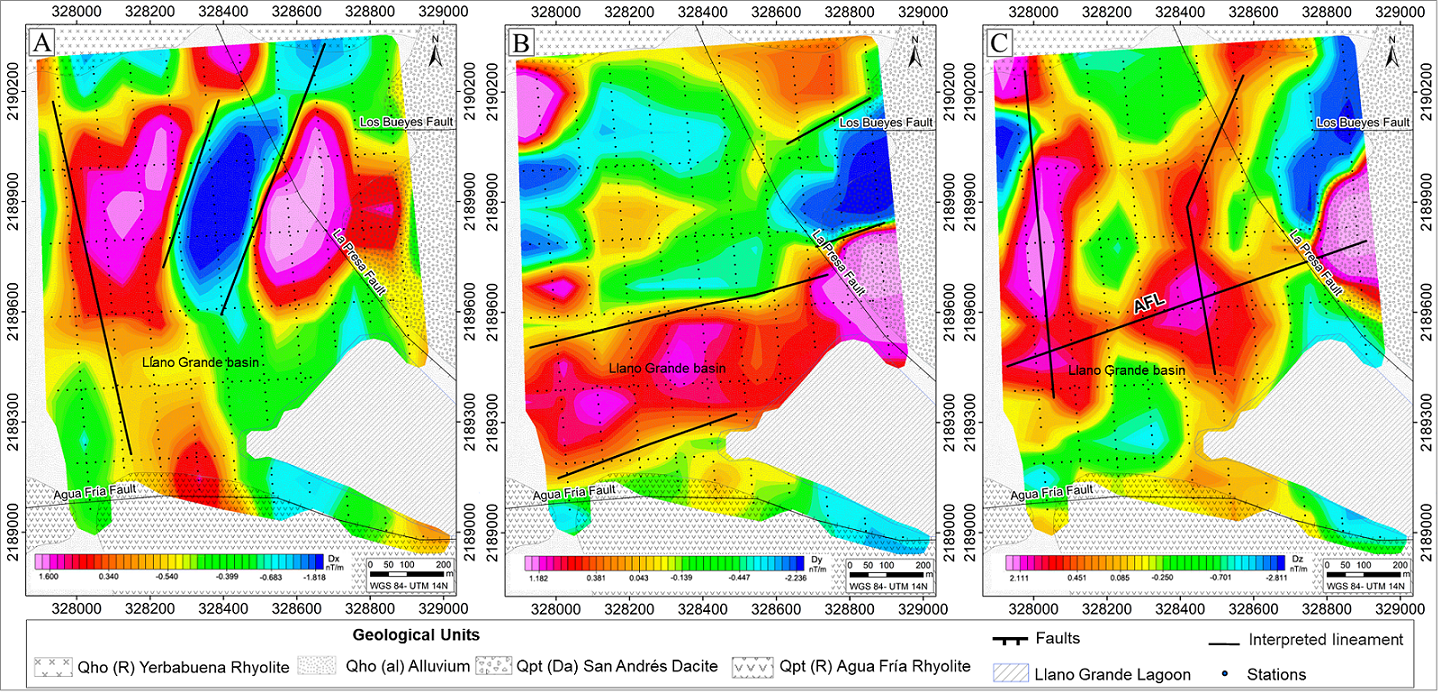

The horizontal derivative maps in both X and Y directions are shown in Figure 5A and 5B). The map of the first horizontal derivative in the X-direction (Figure 5A) reveals that the trends dominating the Llano Grande area are oriented NNW-SSE and NNE-SSW. On the other hand, the map of the first horizontal derivative in the Y-direction (Figure 5B) shows that the most dominant trends are ENE -WSW. The vertical derivative map (Figure 5C) highlighted the edges of the magnetized structures and it reduced the complexity of anomalies observed in the horizontal derivative maps. The main magnetic lineaments in this map trend N-S and NE-SW.

Figure 5 Main interpreted lineaments over the processed magnetic anomaly maps. (A) First horizontal derivative of RTP map in X-direction, (B) first horizontal derivative of RTP map in Y-direction, (C) first vertical derivative of RTP map in Z-direction (FZD). AFL= Agua Fría Lineament.

In this study, we have selected the central magnetic lineament of the basin which we call Agua Fría Lineament (AFL; Figure 5C), to be analyzed by the 2-D profiles. We use this nomenclature based on the fact that this magnetic lineament which extends from the west to the east side of the maps (Figures 5B and 5C), could be the blind extension of the northern segment of the Agua Fría fault mapped from its topographic escarpment between the CFE power plant (LAGF) and the Llano Grande basin (Figure 2A). This fault is suspected to be active by considering its morphology and orientation so its neotectonic study is challenging for the evaluation of seismic hazard.

4.2. THE 2D GPR SURVEY

Two sub-parallel GPR profiles have been surveyed across the ENE-WSW main magnetic lineament previously identified (Figure 6). By considering an average velocity of electromagnetic waves of 0.1 m/ns to unconsolidated alluvial materials (Annan, 2001; Jol and Bristow, 2003), the penetration depth is about 5 m on average for the 100 MHz antennas.

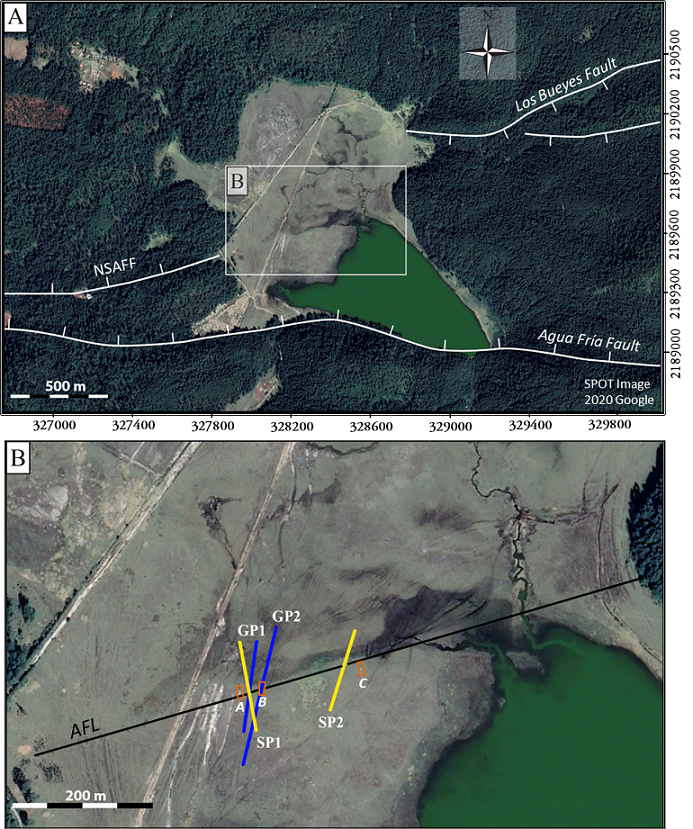

Figure 6 Aerial photographs of the Llano Grande basin showing (A) the location of known crustal faults (NSAFF= Northern Segment of Agua Fría Fault) and, (B) the location of the Agua Fría Lineament (solid black line), the GPR and seismic profiles and Campos Medina (2018) trenches. Yellow lines= Seismic profiles, blue lines=GPR profiles, orange boxes=trenches (labeled A, B, C).

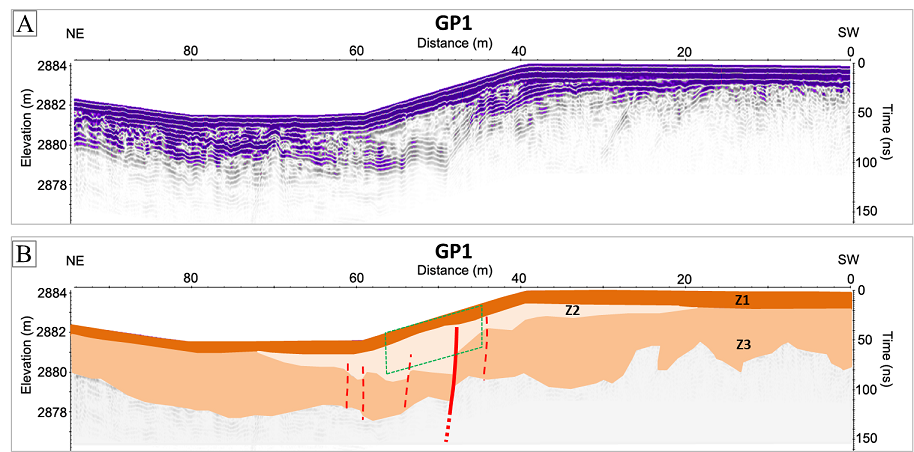

In the profile GP1, three zones can be identified based on the reflection pattern in the processed and un-interpreted radargram (Figure 7A). The upper zone, located between 0 and 20 ns (Z1; Figure 7B), is characterized by high reflectivity, sub-horizontal signals of about 0.5 m thick. These layers lie over a high-attenuation intermediate unit (about 1 m thick), characterized by a chaotic reflectivity pattern and by gentle NE-dipping layers (Z2; Figure 7B). At the bottom, the third zone is characterized by hyperbolic diffractions describing a group of NE-dipping reflectors (Z3; Figure 7B).Between 40-60 m along the profile GP1, a series of reflector discontinuities are indicated with red continuous and segmented lines that cross sub-vertically all the reflector sequences in the record GP1 (Figure 7B). The discontinuities describe a 1 m vertical offset of the sequences.

Figure 7 GPR profile GP1 acquired using 100 MHz antennas across the Agua Fría Lineament. (A) Processed and un-interpreted profile, (B) processed and interpreted profile. Green dotted lines box shows the lateral projection of the 3A trench of Campos Medina (2018) on the GPR profile. The different colors represent changes in the electromagnetic response. Z1, Z2 and Z3 refer to the three zones described in the text.(Vertical Exaggeration=~2.4x).

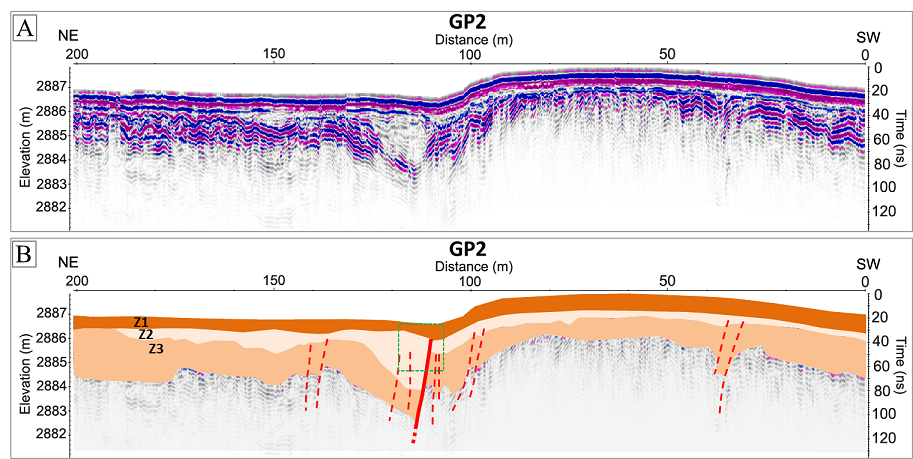

Similar to that described for GP1, the high resolution obtained for the profile GP2 allows defining three main zones based on reflection pattern in the processed and un-interpreted profile (Figure 8A). The first two upper zones are very similar to those described in profile GP1 (Z1; Figure 8B). On the other hand, in the third zone, a fold-type reflector sequence is observed in the record (Z3; Figure 8B). This reflection pattern is different from those flat-type reflector sequences observed in the third zone of the profile GP1 (Z3; Figure 7B). In the record GP2, red continuous and segmented lines indicate the reflector discontinuities that cross sub-vertically all the reflector sequences (Figure 8B). At about 110 m along the profile, distorted radar reflectors exhibit an almost 1.5 m vertical offset.

Figure 8 GPR profile GP2 acquired using 100 MHz antennas across the Agua Fría Lineamentt. (A) Processed and un-interpreted profile, (B) processed and interpreted profile. Green dotted lines box shows the lateral projection of the 3B trench of Campos Medina (2018) on the GPR profile. The different colors represent changes in the electromagnetic response. Z1, Z2 and Z3 refer to the three zones described in the text. (Vertical Exaggeration=~6x).

4.3. SEISMIC REFRACTION

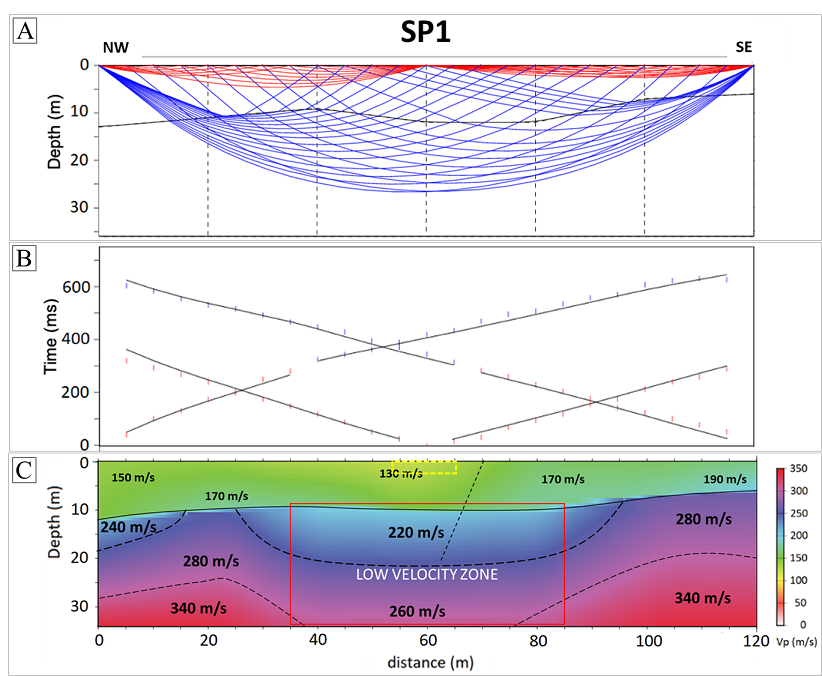

Two 120 m long seismic refraction profiles, SP1 and SP2, were surveyed on the AFL, approximately parallel to the GPR profiles (Figure 6). Profile SP1 has a NW-SE orientation, perpendicular to the magnetic lineament. SP1 ray-tracing model are shown in Figure 9A. The first arrivals, picked from seismic sections fitting the calculated travel times from forward modeling is shown in Figure 9B. Profile SP1 shows a gradual vertical increase in the P-wave velocity from approximately 130 m/s at the top to 340m/s at the bottom (Figure 9C).

Figure 9 Seismic velocity model obtained for the profile SP1. (A) Ray-tracing model, (B) time arrivals from seismic section (vertical colored dashes) and calculated times from forward modeling (solid black lines), (C) Interpolated color-scaled velocity model. Dotted lines show abrupt lateral velocity change and the low-velocity area in the center of the profile is highlighted with a red rectangle. Yellow dotted lines box= lateral projection of the 3A trench of Campos Medina (2018) on the seismic profile. (No vertical exaggeration).

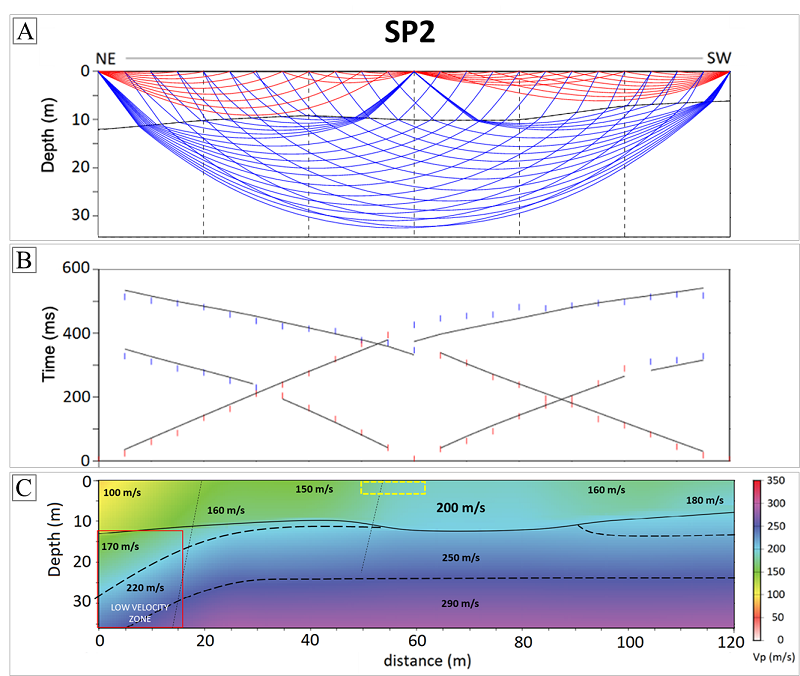

Abrupt P-wave variations between 40-60 m/s are indicated with black segmented lines. A low-velocity zone is visible between 35 and 85 m along the profile which extends to depths of up to 35 m (red box; Figure 9C). Profile SP2 has a NE-SW orientation and has also been surveyed crossing the AFL (Figures 6). SP2 ray-tracing model is shown in figure 10A. The first arrivals, picked from seismic sections fitting the calculated travel times from forward modeling are shown in figure 10B. A gradual vertical increase in the P-wave velocity is visible from minimum velocities of 100 m/s (top NE side of the profile) to 290 m/s. The velocities obtained for this profile are lower than those observed in SP1. Velocity variations of at least 40 m/s are indicated with black segmented lines. Two abrupt lateral velocity variations (black segmented inclined lines) are observed at approximately 15 and 50 m along the profile in the upper sequences. In profile SP2, the lowest velocities are visible in the northeastern part of the profile. Lastly, a low-velocity zone that deepens below 10 m is indicated with a red box at a distance between 0 and 15 m along the profile (Figure 10C).

Figure 10 Seismic velocity model obtained for the profile SP2. (A) Ray-tracing model, (B) Time arrivals from seismic section (vertical colored dashes) and calculated times from forward modeling (solid black lines), (C) Interpolated color-scaled velocity model. Dotted lines show abrupt lateral velocity change and the low-velocity area in the center of the profile is highlighted with a red rectangle. Yellow dotted lines box= lateral projection of the 3C trench of Campos Medina (2018) on the seismic profile. (No vertical exaggeration).

5. Discussion

For the evaluation of the seismic hazard, obtaining parameters such as the cartographic length of the faults, their geometry and the width of the fault zone is crucial. During the past decades, the faults bordering the Agua Fría graben have been described and mapped by structural analysis or photo interpretation (e.g.De la Cruz et al., 1983; Dobson and Mahood, 1985; Garduño-Monroy, 1987). However, the presence of faults within the micro-graben, less visible in morphology, was poorly constrained and therefore was not reported or was imprecisely mapped. In particular, the northern segment of the Agua Fría fault had never been mapped before our group identified it for the first time and determined with this study its possible continuity in the sedimentary filling of the Llano Grande basin that could neither be demonstrated nor discarded from classical geological observations.

The magnetic anomalies exhibit a high and low amplitude related to volcanic rocks (basement) and sediments, respectively. In general, the results of the interpretation of the magnetic anomaly maps correlate well with the known local geological contacts, faults, and structures (see Figures 2, 3, and 5). The anomaly A, identified in both the RMF and RTP maps (Figure 3), could be associated with the strongly magnetized volcanic rocks present in the La Yerbabuena Rhyolitic unit (Dobson and Mahood, 1985; Macias et al., 2008). In the same way, the anomaly C could correspond to the magnetic signature of the volcanic rocks forming the San Andrés dacitic dome (Dobson and Mahood, 1985). Combinations of directional derivatives of the magnetic data surveyed over the Llano Grande basin (Figure 5) allowed the identification of potentially important structures which cross the basement of the Llano Grande basin. Some solutions indicate the presence of lineaments that are possibly related to buried NE-SW and NNW-SSE faults. Although anomalies A and B are parallel to the NNW-SSE La Presa fault they would represent the southern prolongation of the Laguna Verde fault under the alluvial deposit. The alignment formed by anomalies B and C would correspond to the upthrown block of the Laguna Verde fault where structural highs of the Rhyolite may be buried. These structures are associated with the Basin and Range tectonic provinces and have been documented and referred to the eastern limit of the producing area of the geothermal field (e.g.De La Cruz et al., 1983; Dobson and Mahood, 1985; Garduño-Monroy et al., 1987; López-Hernández, 1991). Gradients with ENE-WSW and E-W orientation could correspond to faults accommodating the current N-S extension in the TMVB, similar to that reported by Campos-Enríquez and Garduño-Monroy (1995) in their regional study. We then focused our GPR and seismic refraction studies on the clearest WSW-ENE lineament called herein the AFL. This magnetic lineament crosses the entire study area and most likely corresponds to one of the potentially active faults intersecting the Los Azufres volcanic edifice (Figure 6).

Regarding the GPR data, the most apparent features in the two profiles are the diffraction hyperbolas and layer truncations. These are related with strong lateral contrast in permittivity across each material and are consistent with the presence of a fault or other geologic structures affecting the basement, as already previously highlighted in the literature (e.g.Busby and Merritt, 1999; Bano et al., 2002; Pauselli et al., 2010; Ercoli et al., 2013).

The two GPR profiles show reflector discontinuities which allow interpreting the AFL as a north-dipping normal fault displacing relatively shallow and therefore potentially recent sedimentary units (Figures 7 and 8). Inclined and distorted radar reflectors between 0.5 and 4 m depth indicate a deformation by 1 m to 1.5 m between the two blocks. Exploratory results of this study allowed the location of paleoseismic excavations reported preliminarily in the Master thesis of Campos Medina (2018). Three trenches were dug perpendicular to the fault and two of them are almost located on the axis of the radar profiles (location in Figure 6B; Campos Medina, 2018). The two trenches show an offset of the sedimentary units along a north-dipping fault which varies between 1.48 and 1.80 m in total.

This deformation is distributed over a more or less wide fault zone. Trench A shows a very localized fault zone with a single north-dipping fault which accommodates all the displacement on one wall and a slightly more complicated fault zone on the other wall (two north-dipping synthetic faults and one south-dipping antithetic fault). For trench B, the fault zone is more complex and in the trench, only a fault propagation fold is visible accommodating the tectonic deformation over a 5 meters wide area. The fault zone is not visible in the trench which only exposes the first 2 m of the subsurface. The analysis of these trenches shows the reliability of the GPR for imaging such structures, both to locate them precisely in a landscape without clear morphological expression and to estimate the geometry, displacement and width of the fault zone which are of the same order of magnitude on the GPR profile and in the trenches.

The low-velocity zone identified in the seismic profile SP1 (Figure 9) corresponds geographically with the location of the fault previously highlighted by the GPR. In the profile SP2 (Figure 10), the abrupt lateral velocity variation at 50 m along the profile corresponds with the location of the AFL, while the lateral velocity variation at 15 m along the profile seems to correspond with the location of a gully identified by field observations. The low-velocity zone and the abrupt velocity variation in the seismic profiles are related to the variation of acoustic properties of materials, and it could correspond to altered rocks by fluid circulation along and in the vicinity of the fault plane as suggested by some authors (e.g.Pellerin and Christensen et al., 1998; Yan et al., 2005).

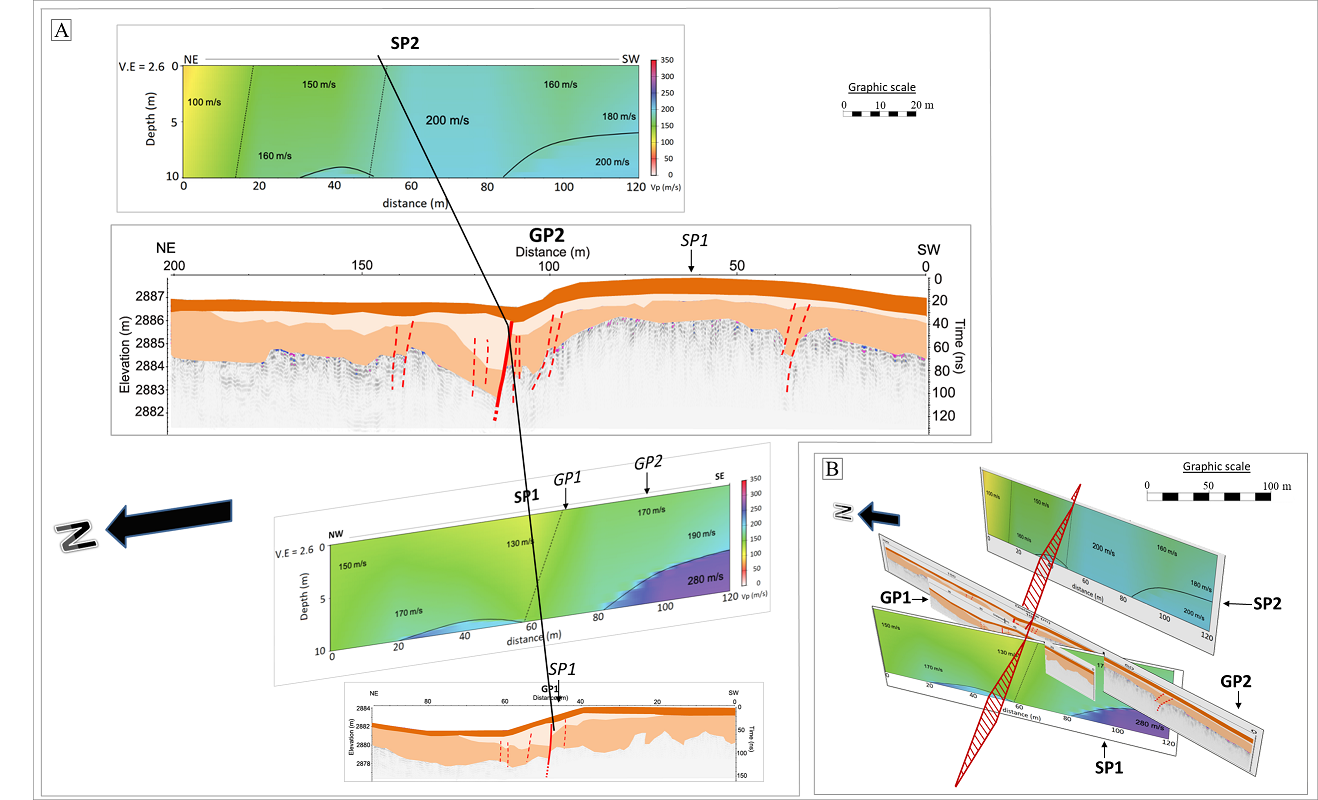

Figure 11 presents an overlay of the two GPR profiles (GP1 and GP2) with magnified views (up to 10 m depth) of the SP1 and SP2. This figure shows a strong correlation between both data sets and can be used to image and characterize the lineament highlighted in the magnetic maps and then to interpret it as a north-dipping normal fault displacing relatively shallow sedimentary units. The offset (vertical displacement) is about 20 ns in the radargrams. Using 0.1 m/ns velocity to time-depth conversion, give us an average vertical displacement of 1 to 1.5 m between reflectors with the same electromagnetic properties. Such displacement is compatible with the paleoseismic observations preliminary reported by Campos Medina (2018).

Figure 11 Correlation of interpreted GPR records and magnified views up to 10 m depth of the seismic refraction profiles SP1 and SP2. (A) Plan view of interpreted GPR and seismic profiles at the same horizontal scale. The black line indicates the interpreted fault trace. (B) 3D view showing the relative distance between profiles according to the graphic scale. The red polygon indicates the estimated fault plane of the northern segment of the Agua Fría fault.

Considering the location and the northward dip of the fault, we assume that this structure corresponds to the eastern prolongation of the northern segment of the Agua Fría fault (NSAFF) preserved in the morphology of the rhyolitic formations between LAGF and the Llano Grande basin as shown in Figure 12. Considering the surface sedimentation in the Llano Grande active basin, such deformation could be Holocene and according to the criteria proposed by Audemard (2003, 2005), this site was suitable and therefore the object of paleoseismological study which confirmed our preliminary interpretations (Campos Medina, 2018).

6. Conclusions

Three complementary shallow geophysical techniques were used to image the structures affecting the basement of the Llano Grande basin in the Los Azufres volcanic field. The Total Field Magnetic data led us to identify anomalies and lineaments of different orientations. The GPR and seismic refraction techniques allowed us to structurally characterize the main magnetic lineament identified in the basin and to interpret it as a high angle north-dipping normal fault. The good resolution GPR data show inclined, distorted and displaced reflectors between 0.5 and 4 m depth allowing estimating the offset of the more superficial deposits in about 1-1.5 m. The GPR data, in this context, allow: 1) precisely locating the fault zone, 2) estimating the offset of the displaced sequences. In turn, the seismic refraction results indicate that the deformation extends in depth to more than 10 m and the horizontal width of the disrupted area associated with the fault is about 40 m but it increases with depth.

This fault is interpreted as the eastern prolongation of the northern segment of the Agua Fría fault hidden under the sedimentary cover of the Llano Grande basin. In this area, the GPR technique is the most effective to illuminate and characterize the fault zone. However, the other applied techniques were essentials to locate the main lineament in the basin and therefore to specify the interest area. The realization of paleoseismological trenches based on these results, allowed validating the precision in the geophysical localization of the fault as well as the accuracy of the interpretation of the GPR profiles.

Our results allow identifying, locating with precision, and characterizing a structure hardly visible on the surface and therefore unknown. This potentially active fault could have ruptured during the Holocene by considering the active sedimentation of the basin of Llano Grande. In such a context, this study is an essential step to carry out paleoseismological studies along the faults of the Los Azufres volcanic field.

At the scale of the fault systems affecting the central TMVB, the Agua Fría graben is an excellent analog of the 10 to 20 times larger tectonic basins formed by the faults forming the MAFS. The identification of potentially active structures under the Quaternary sedimentary filling of the Llano Grande basin allows improving both the cartographic precision and the estimation of the length of faults, as well as to constrain the relation between the different faults of the same system.

This work confirms the relevance of the use of such geophysical multidisciplinary techniques for the identification and characterization of buried structures before the excavation of paleoseismic trenches. Such studies would be relevant, for example, in most of the tectonic basins bordered by the faults from the MAFS. In fact, in most of these basins, there is no information available on the presence of blind faults and their extent. These structures lack surface expression but the potential tectonic activity is important to be considered for the evaluation of the seismic hazard.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)