Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Convergencia

versión On-line ISSN 2448-5799versión impresa ISSN 1405-1435

Convergencia vol.24 no.74 Toluca may./ago. 2017

https://doi.org/10.29101/crcs.v0i74.4380

Scientific Article

Smugglers who cheat migrants: rule or exception

1Universidad Autónoma de Tamaulipas, México. sizcara@uat.edu.mx

This article, based on a qualitative methodology that includes in-depth interviews with 90 migrant smugglers, 20 procurers and 60 immigrants from Central America, examines the smugglers who cheat migrants. The results of this research indicate that many migrant smugglers only have the purpose to rob, kidnap or abandon migrants; that sex trafficking networks, which operate with some degree of deception, are growing; and that more and more migrant smugglers leave this industry, voluntarily or involuntarily, to join drug cartels. However, the main conclusion from the discourse of the interviewees is that there are more smugglers who lead migrants safe and sound to the United States than those who attack and do not care about them.

Key words: migrant smugglers; undocumented migration; prostitution; organized crime; Mexico; United States

Este artículo, fundamentado en una metodología cualitativa que incluye entrevistas en profundidad con 90 polleros, 20 proxenetas y 60 inmigrantes centroamericanos, examina a los polleros que engañan a los migrantes. Los resultados de esta investigación indican que muchos polleros sólo tienen la intención de robar, secuestrar o abandonar a los migrantes; que cada vez hay más redes de tráfico sexual, las cuales operan con cierto grado de engaño, y que cada vez son más los polleros que abandonan el coyotaje de forma voluntaria o involuntaria para formar parte de los cárteles de la droga. Sin embargo, la principal conclusión que se desprende del discurso de los entrevistados es que son más los polleros que conducen a los migrantes sanos y salvos a Estados Unidos que aquellos que los agreden y no los cuidan.

Palabras clave: polleros; migración indocumentada; prostitución; delincuencia organizada; México; Estados Unidos.

Introduction

Over the last decade, Mexican and American migration policies have turned into national security policies and coyotaje (human smuggling) has been equated with other threats: drug and gun trafficking, and terrorism. Matching undocumented migration and terrorism has been associated with a change in the perception of coyotaje. The argument wielded in the official discourse is that in the past coyotaje was a pacific activity run by people who were part of the migratory wave; conversely, at present organized crime has taken over this activity, which means a threat for migrants and national security (polleros abuse the migrants, rob, kidnap and abandon them; while the same networks that smuggle migrants transport arms, drugs or terrorists).

This article’s goal is to identify the polleros1 who deceive migrants, seek personal profit and rob and abandon migrants and to find out whether these are an exception or the norm in this activity. The research question, smugglers who deceive migrants are the norm or an exception? is of the utmost importance, since if these are the norm, the harsh border-control policies are suitable as they protect the migrants’ lives and hold national security threats; on the contrary, if these smugglers are an exception, then the costly border control policies, from the social and economic standpoint, are not justifiable for they violate the migrants’ human rights. In the first scenario, the State is a victim and deaths at the border are only attributable to the avarice of networks which profit on migrants. In the second scenario, the State is the aggressor.

This article examines the smugglers who deceive, rob, abandon and exploit migrants. In the first place, the methodology of the study is described, then the profile of unscrupulous smugglers is analyzed and those who rob and abandon migrants are examined; finally, smugglers involved in sex traffic and drug dealing are studied.

Methodology

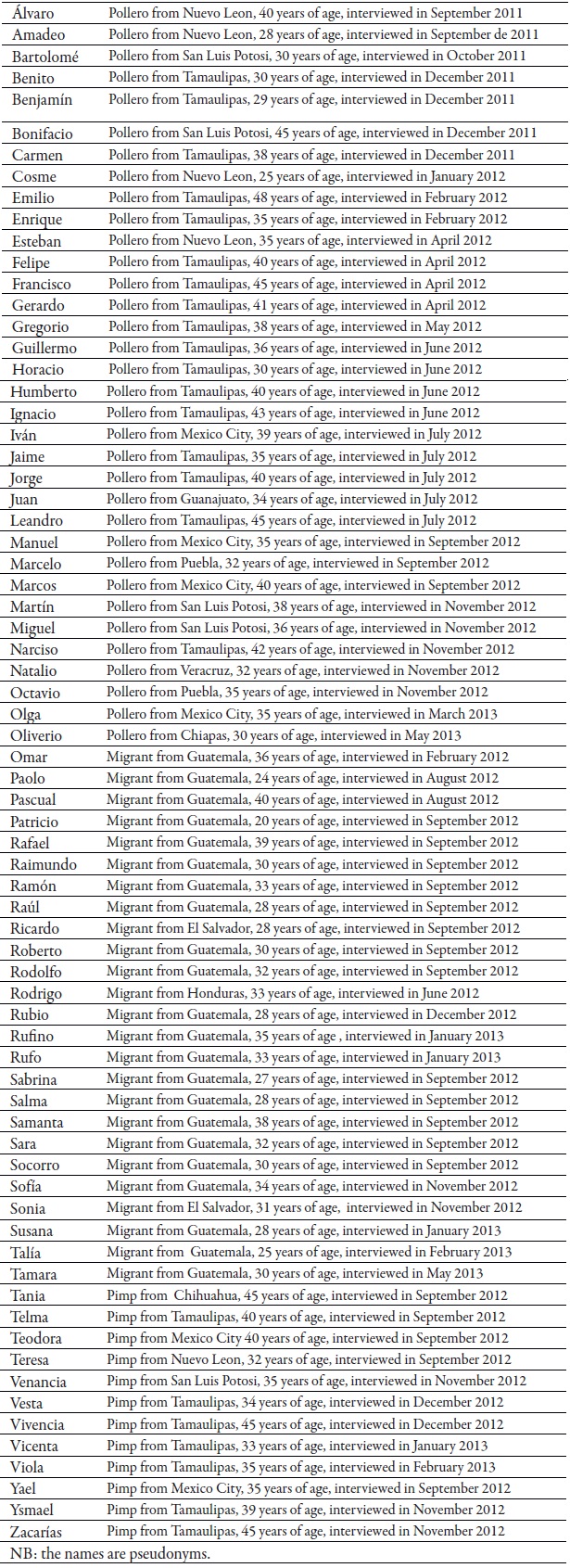

This research is supported on qualitative methodology. The technique utilized to gather information was in-depth interview. The interviewees were visited twice. The first meeting lasted was over an hour; while the second was shorter and dealt with aspects not concluded the first visit.2 The interviews were recorded and transcribed. Moreover, the procedure to select the interviewees was chain sampling.

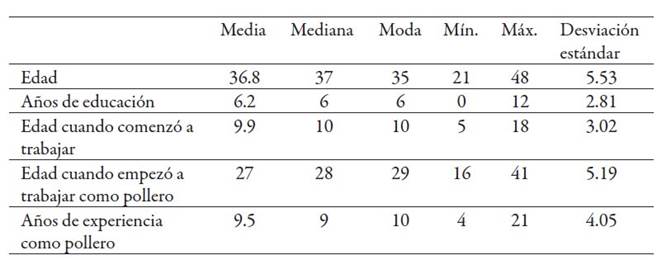

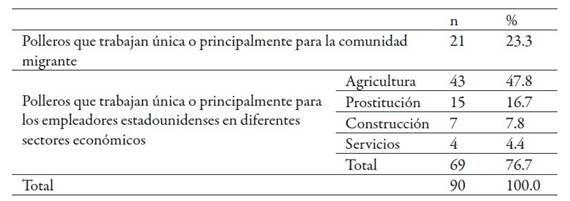

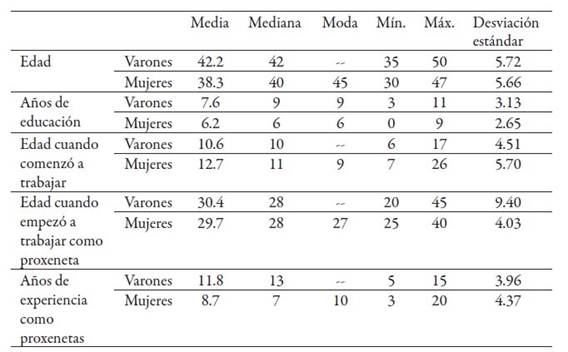

Fieldwork was undertaken at various places in Tamaulipas, Nuevo Leon, San Luis Potosi and Mexico City. Between the months of April 2000 and May 2013, 90 polleros were interviewed. They were 36.8 years on average, had an average schooling of 6.2 years and entered the labor market before being 10 years of age. The respondents started to work as actors who facilitated the border crossing, between the ages of 16 and 41, and on average they accounted for 9.5 years of experience practicing this activity (see table 1 3). Twenty-three percent worked only or mainly for the migrant community; while, 77% provided American employers with migrants (see table 2). The respondents recruited immigrants both in Mexico and Central America.

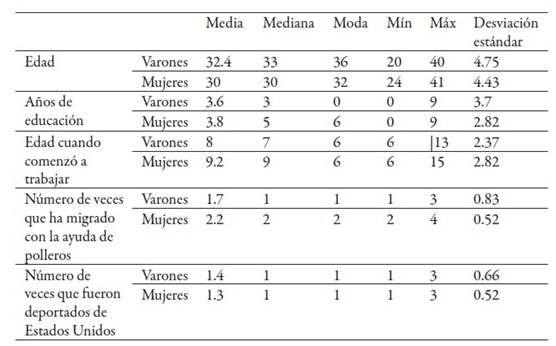

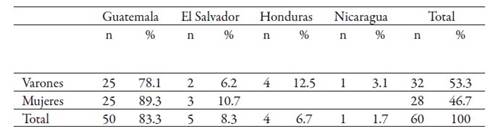

Between the months of June 2012 and May 2013, 60 Central American trans-migrants were interviewed (32 men and 28 women). Men were 32.4 years on average, whereas women, 30 years. Men only had 3.6 years of middle schooling, and women had 3.8 as they had to entre the labor market early to contribute to their family economies. Men started to work, on average, at 8 years of age and women at 9.2. All the respondents had been deported from the U.S. were stranded in Mexico4 and had a background in migration to the US helped by a smuggler. Women had traversed Mexico guided by polleros 2.2 times on average and had been deported 1.3 times; while men hired polleros 1.7 times and were deported 1.4 time son average (see table 3). Besides, as noticed in table 4, 83% of the respondents came from Guatemala, and the rest were from El Salvador, Honduras and Nicaragua. Men had found employment in diverse activities, whereas all women had experience working on prostitution.

Finally, between the months of September 2012 and February 2013, 20 Mexican pimps were interviewed (15 women and 5 men); they recruited women for sex trafficking. The pimps’ average age was 42.2 for men and 38.3 for women. Men had 7.6 years of schooling and women, 6.2., men started to work at an average age of 10.6 years, while women at 12.7, but did not become pimps until they were on average 30.4 and 29.7 years, respectively. While the former had an experience of 11.8 years, women had an experience of 8.7 years (see table 5).

Unscrupulous smugglers: norm or exception

The academic discourse on coyotaje moves between a hegemonic position, which verifies that unscrupulous polleros are the norm, and other more marginal that considers these an exception. However, while the first stance rarely gathers the discourse of the actors that facilitate border crossing, the second largely support these individuals’ account.

The discourse in which polleros are described unscrupulous criminals justifies the harsh border-control policy enacted by the United States in the areas close to the largest populations and more easily accesses, as it releases the authorities from any responsibility in the increase of migrants’ deaths at the border. The official discourse was quick to blame the actors who facilitate the crossing on such deaths, as they disregard the migrant’s lives searching for profit: they rob, assault, rape and abandon them (HCHS, 2006: 18). For Nevins (2003: 175), Washington’s attempt to hold coyotes accountable for such deaths only tries to hide the actual culprit: the infrastructure that makes it more difficult to cross over urban areas.

The academic discourse has recurrently blamed the deaths of migrants on the smugglers’ greed, who abandon them in the middle of the desert where their survival probabilities are scarce (Guerette and Clarke, 2005; García-Vásquez et al., 2007: 104; Addiechi, 2005: 174 ). Numerous studies evince that migrants do no trust polleros any longer, as they are no longer the usual common people of domestic networks (Márquez-Covarrubias, 2015: 161 ; Martínez et al., 2015: 134; Slack et al., 2016: 22 ).

Even if the deaths at the border are attributed to the migratory policy, which explicitly intends to dissuade migrants from crossing, smugglers are described as members of criminal organizations that victimize those who hire their services (Feldmann and Durand, 2008: 23). Slack and Whiteford (2010: 89) recognize that the prevailing discourse that depicts coyotes as criminals is biased, however they point out that robbery, drug trafficking and sex slavery are elements that cannot be detached from a coyote’s daily functioning. Because of this they criticize Spener’s (2009) stance, who with the exclusion of robbery, drug trafficking and sex slavery from his analysis builds an excessively positive image of coyotaje.

This discourse distinguishes the current situation, characterized by the presence of human trafficking networks operated by organized crime, which abuse and mistreat the migrants, from a previous situation in which polleros cared for the migrants; however, in the mid XX century, coyotes were not defined very differently from the way they are now.

According to Thompson (1956: 78), the hardening of the 1885 Alien Contract Labor Law by means of the approval of the Immigration Act of 1917 made many farmers resort to coyotes, whom the author defined as people without scruples that deceived migrants and took them into the U.S. “gathered in large masses as if they were cattle”

A reduced number of academicians considers that the smugglers that exploit migrants are an exception. Spener (2009: 155) defines people who deceive migrants as false coyotes: individuals who pretend to be polleros. For Spener (2011), coyotes and migrants partake of a strategic alliance of resistance before the repressive structure of the global apartheid set into motion at the borders of the states. Sharma (2003: 60) goes beyond and defines the actors that facilitate the border crossings as a group of people that helps migrants.

Other researches have verified that most of the smugglers lead migrants safe and sound to their destination (Spener, 2004: 298 ; Kyle and Scarcelli, 2009: 306 ; Achilli, 2015: 6; Parks et al., 2009: 51 ), that most migrants do not report an abusive treatment (Kimball et al., 2007: 104 ; Fuentes and García, 2009: 89 ), that coyotaje is an activity separate from drug dealing (Fuentes and García, 2009: 98; Spener, 2009: 156) and that this is a nonviolent activity carried out by common people (Sánchez, 2016: 404 ).

All the respondents recognized that some polleros deceived migrants. Jaime said categorically: “there are polleros who do not care for the people they take, or those who sell them, that is true”. However, none of the respondents included themselves in this category; quite the contrary, some defined themselves as social benefactors.

This is reflected in expression such as “I like being a pollero because I help people” (Gerardo) or “I feel that by being a pollero I help people” (Guillermo). They know that people increasingly distrusts this profession; this way, many try to become friends with their clients. Esteban said: “I also try they see a companion in me that is going to take them, and a friend, I try that they feel safe”.

Some said that the most rewarding of the activity they performed was to see how their countrymen prospered economically. As pointed out by other studies (Achilli, 2015; Sánchez, 2016), almost everyone defined their profession as a decent and honorable job. Manuel expressed: “it is a job in which I don’t steal or do bad things; for me it’s a decent honest job”. Likewise, Zhang et al. (2007: 712 ) found that the Chinese actors that facilitated the crossings had a positive opinion of the activity they carried out, and for many helping others reach a better life was a reason for satisfaction.

Sánchez (2015) explains that the economic motives of the actors that facilitate the crossing are, on occasion, not as important as the social motives, for instance: help others migrate. Achilli (2015: 6) also found cases in which ethics was favored over profit.

Many of the respondents pointed out that the hardest part of their profession is to be responsible for transporting the migrants safe and sound to their destination. The militarization of the border has increased risks for coyotaje as the most easily accessible terrains in the U.S., where migrants are in least danger, are heavily guarded. Therefore, they must use more dangerous routes (Parks et al., 2009: 36 ; Spener, 2009: 45 ).

In each new trip new contingencies are faced: an animal’s bite, someone delayed or dehydrated. They say that migrants are like children who they have to care for. In terrains so dangerous, the probability of survival of an adult is not over that of a child. They say that the angst of moving people so fragile and defenseless, who walk blindly on a terrain with so many dangers, produces them a knot in their stomach, which is not fear but responsibility.

They are under my charge and I have to take care of them, this is the most difficult for me, keep them from the dangers of the road (Gregorio).

Still knowing your way you wonder: what’s going to happen? You don’t know if an animal comes out or if someone dehydrates or falls, you know nothing, it is despair what you feel inside, it’s not fear, is the burden of responsibility (Juan).

I’m responsible for them, because they go into the unknown, because they don’t know and for me they are like children and I can’t deceive them (Marcos).

Smugglers are people with deep religious beliefs. They believe god protects them, but they also think he is vengeful and will take revenge if they abuse the migrants. Cosme said: “if God guides me and looks well after me as he sees I have never done anything against God’s word; I’d rather die than hurting other people”.

In like manner, Benjamín stated: “you are accountable for them and you have to take good care of them, to the cost of your life”. Carmen told how on occasions she had to face Mexican authorities, exposing herself to detention in order to prevent them from abusing the women she took. By the same token, Horacio told that on one occasion he was caught by American migratory authorities because he saved a migrant drowning in Rio Grande. But not only are the polleros the ones that define as benefactors who risk their lives for the migrants, as the latter state so, as Rufino pointed out:

By and large, polleros are good, they risk their lives to help us […] They risk their lives for people who sometimes they don’t know, as it is the case of us, Central Americans, who travel in Mexico […] What I mean is that polleros are good and make their living by crossing people across Mexico or into the U.S.; they are good because in spite authorities say the contrary and treat them badly, polleros have helped a lot of people.

Smugglers who rob and abandon migrants

Migrants who hire polleros to reach the U.S. risk the latter take their belongings (Kimball et al., 2007: 97 ; Spener, 2009: 155 ), abandon (Cueva-Luna and Terrón-Caro, 2014: 234 ; Slack et al., 2016: 16 ; Martínez, 2016: 113 ) or kidnap them (Slack, 2016: 274; Slack and Campbell, 2016: 10). The respondents knew from experience that some polleros deceived and abandoned the migrants. Some polleros helped migrants, who abandoned by their guide, were left stranded in the territory; others told cases of migrants who found themselves with no money because they were cheated, and others knew of polleros who took people in and forced them into semi-slavery.

I have seen how polleros abandon people on the road (Enrique).

There are bad polleros that do not care for the migrants, who deliver them to criminals (Gerardo).

There I found a person they have kidnapped, they had asked for a ransom, and told him they would take him to the US. But they didn’t, they only crossed him and left him stranded, we found him on the road (Humberto).

There are polleros who abandon the people with them, everyone is for themselves, they left the migrants in danger, abandoned, and without a single contact (Ignacio).

There are polleros who take people in and sent them to a boss who makes them work hard, and sometimes the migrants don’t get paid (Iván).

The respondents attribute the bad reputation to the coyotes who pursue personal profit, whom they define as fake polleros. This way, Spener (2009: 155) defines false coyotaje as those individuals who offer to take migrants to the U.S., but their only intention is to rob them.

Natalio said: “for me, the wrongdoers are not polleros, but pretend they are to deceive and mug migrants”. Some migrants also think that the ones who deceive are not real polleros. Susana claimed: “I met a Brazilian and a Salvadoran who hang around and they told me that a pollero had kidnapped them, but I told them that was no pollero, he was a delinquent, that’s why he deceived you”.

The respondents underscore that the number of polleros who took migrants safe and sound to their destination was larger than those who abandoned them. Likewise, Parks et al. (2009: 51) found that all migrants from Tlacotepec who hired a pollero reached the United States successfully. However, they also said there were always people who tried to deceive them. Therefore, those who do not look into the background of guide are in danger. As Francisco said: “there are polleros who cheat people and abandon them, but not everyone is like that, here people who want to go have to look for people to advice them, to recommend them for their best security”.

Not only are those with the intention to rob, kidnap or abandon the migrants in the list, but also those with no experience. Crossing the border is increasingly complex, it is heavily guarded and there are new dangers.

The polleros who want to make a name in this profession but lack experience risk the migrants’ lives. Expressions such as “There are more polleros, but have no experience” (Álvaro), “there are polleros with not much knowledge” (Felipe), “there are people with no experience and works that way, and they are scared and do things badly” (Marcelo), “there are new people with no experience and migrants drown or die in the desert from the heat” (Bartolomé), “there are people who disregard those they take and they even die because they do not know” (Bonifacio) or “the polleros who can be bad and deceive people is because they are apprentices” (Miguel), repeat intermittently in the interviews.

Central American migrants have always mistrusted polleros, they know they can deceive them, so they look for references. As Raimundo said: “back then [1997], it was known that polleros abandoned people and deceived them, they said polleros took all their money, that’s why I looked for the pollero I had been told”.

At present, the dangers of irregular migration are greater (Slack, 2016; Izcara-Palacios, 2016). This has increased mistrust toward polleros. Rodolfo said: “people were different before, they didn’t mistrust anyone, polleros were different and they were trusted”. Likewise, Samanta said: “people were different in the past, there was no evil as nowadays, polleros were committed to the people they took, they were responsible and good”.

Sixteen-point-seven percent of the respondents were deceived by the polleros they hired in the last trip (see table 6). Other studies report similar results. Kimball et al. (2007: 104) interviewed 201 migrants from Tunkás (Yucatan, Mexico), and 10.9% was assaulted by criminals colluded with smugglers. For their part, Fuentes and García (2009: 89) interviewed 212 migrants from Tlacuitapa (Jalisco, Mexico) transported to the U.S. by coyotes, and 11.1% reported abuses. Deceit commonly occurs as follows: after paying the polleros, the migrants are asked to wait for them in a restaurant or hotel, however polleros run away, leaving the migrants stranded with no money in a country they do not know.

He left us here, we rested in a motel, he went to buy food and never returned, he took the money away (Raúl).

He charged 2,100 USD to cross me, but thing is he didn’t (Rodrigo).

We stayed at a motel, we took two rooms, one for men and another for women […] but at night the pollero took the women and left us here sleeping (Rufo).

The pollero with us said I have to wait, I waited but he didn’t arrived (Sara).

Polleros that only try to deceive the migrants usually charge lower fees. Therefore, migrants with fewer resources are at greater risk of being deceived. Díaz-González (2009: 35) explains that facing an increase in the risk, honest polleros have to rise their fees, while dishonest, who ex-ante do not consider fulfilling the deal, do not rise it; thereby, the latter will concentrate the demand with the consequential harm to migrants.

However, migrants have learnt to mistrust those polleros who offer low fees. Most wait for weeks for the pollero they were recommended or save money for months to complete the ordinary fee. Less and less they hurry to follow an unknown pollero that offers them a too attractive deal. Parks et al. (2009: 53) also found that migrants from Tlacotepec mistrust the coyotes at the border that charged less.

Central American migrants traversing over Mexico experience high levels of violence both from organized crime and Mexican authorities (Izcara-Palacios, 2016). Facing the graveness of these threats, the perception of the risk of being abused by the polleros seems diminished.

As noticed in table 6, contrasting 17% of the migrants was abused by polleros, a half was attacked by organized crime, and 32% by authorities. Moreover, aggressions from criminal groups have severer consequences than those by polleros (Slack, 2016: 274 ).

Additionally, Doezema (2010: 140 ) has pointed out that authorities are a bigger threat than traffickers. Because of this, as stated by Cueva-Luna and Terrón-Caro (2014: 231), in spite of the risk of hiring a pollero, generally migrants tend to trust in them. This is noticed in expressions such as: “he always took care, he was good” (Omar); “they helped me in what I needed, they were attentive” (Paolo); “they help people” (Pascual); “he was a good man, respectful” (Patricio); they were good, they took women and were kind to them” (Ramón); “they behaved well and took care of us” (Ricardo); “they always helped us and didn’t drop us on the road” (Socorro); “they are good, they treated me nice” (Sofía); or, “polleros are cool” (Sonia).

Many told anecdotes of people who had been cheated, but in most of the cases their experience was positive, reason why they thought there were more good polleros than bad ones. As Rodolfo expressed: “there are polleros who aren’t good and don’t know how to work, but I say that the most are good”. Women are the most resentful; this is noticed in expressions such as: “there are good polleros and there are bad and you don’t know who you go with” (Samanta); “you can’t trust, you go with the pollero, but go with fear” (Sandra); “I wasn’t deceived like many” (Sara).

It is noticeable that some Central American migrants do not deem the high fees that pay excessive. Rafael pointed out: “I think they are people who help people, yeah they charge you well, but they need the money to pay along the road”. Sabrina said: “coyotes charge high because they also have to pay to cross”. This way, Aquino-Moreschi (2012: 14) was surprised by the positive image of polleros among many migrants, who were grateful for the services received, even though they had paid a high fee.

The most surprising is that some migrants who were deceived do not fully mistrust the people who took their money. Rubio, a Guatemalan migrant who in September 2013 paid 30 thousand MXN to a pollero who would take him from Mexico City to the border, said: “this is the first time the pollero leaves me, I don’t know if he made it on purpose or he left and couldn’t come back, he only knows what happened, why he left us, he seemed to be good”.

Rufo another Guatemalan who in December 2012 paid 25 thousand MXN to a pollero to take him from Coatzacoalcos (Veracruz) to the border, stated: “the treatment they gave was good, what I don’t understand is why this last pollero abandoned us and left us knowingly we didn’t know the place”.

Coyotaje and sexual exploitation

Networks to transport women for the adult entertainment industry have been associated with deception, violence and slavery (Agustín, 2007: 39 ; Hua, 2011: 44 ; Doezema, 2010: 138 ). For Spener (2009: 159 ), sexual trafficking is not part of the usual strategies of coyotaje. However, it is a growing strategy in coyotaje at the Mexico-U.S. border. Many adult entertainment centers in the U.S. take in women who were made to cross the border illegally.

There are connections between some American and Mexican adult entertainment centers; in some cases connections are direct.

As Viola said: “the bar owners in the U.S. know the bar owners in Mexico, they chat and interchange women so that they work more and make more money”. But in most of the cases, connections are indirect. The owners of these entertainment centers hire Mexican polleros to take women for them, these people recruit women in bars, taverns and whorehouses in Mexico. The women demanded in the U.S. are the youngest and most attractive. Years later, when they lose their attractiveness, usually return to Mexico.

Connections between Mexican pimps and polleros are tight. Expression such as: “Apart from being a pimp, I also help polleros with the people” (Yael), “we can help the girls to go to the US ‘cause my son is pollero” (Tania), “there are polleros who come to look for women here” (Vesta), “there is a pollero that is my friend, he comes here as if it was his home” (Vivencia), or “the pollero is my homie, my brother, I’ve known him for years” (Vicenta) underscore the bonds that unite polleros and pimps.

The former recruit women for the latter; but this is not usually done by deceiving. For pimps to deliver one of their workers to a pollero entails loss of incomes, as these only look for the youngest and most attractive, who generate more incomes. Besides, they receive little money; the respondents refer to figures between five hundred and three thousand MXN per women.

By and large, pimps give coyotes those women with the firm intention to work in the U.S. The former are benefitted either if a woman goes or stays; if the woman goes to the United States, the pimp receives a commission from the pollero; if she does not go, he receives part of her earnings. Talía a woman recruited by a pimp in Chiapas, in 2014, when she was 16, to work in the U.S., expressed:

There [in Chiapas] he had a brothel, a tavern, he had it there to hook women and offered them a job in the United States, those who accepted went north, and those who didn’t, well they kept working in the tavern, anyway he [the pimp] didn’t lose a thing, on the contrary, he earned money from those he sent and those who stayed to work as prostitutes.

Another benefit pimps obtain from polleros is the periodical availability of new women. Clients soon become bored with the women who work in adult entertainment centers; this way, places where there is heavy rotation of women are the most popular. Polleros recruit women in these centers, but those who they transport also work there for some time. Frequently these establishments are also safe houses where women rest and work. Women with not enough money to reach the United States usually remain longer in these places, when they save to pay the pollero, he picks them up.

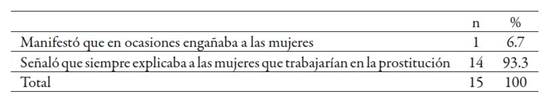

Coercion is not a usual recruiting method used by sexual trafficking networks. Numerous studies have verified that many of the female migrants who work in sex industry knew beforehand the nature of the job they will perform in the recipient country (Agustín, 2007: 30 ; Doezema, 2010: 9 ; Lim, 2014: 14 ; Weitzer, 2015: 235 ). All the respondents engaged in sex trafficking, save one, stated that women were never deceived (see table 7). Expressions such as: “we tell them in Mexico and they come, and tell them what the job will be like” (Miguel), “I take those who want to go […] because they know me and recommend me” (Narciso), “always go those who want, I don’t take them by force, or deceive or lie to them” (Octavio) or “they are not taken by force or deceived, it’s because they want to go” (Oliverio) are repeated in almost all interviews.

In like manner, the pimps interviewed argued that coyotes cannot resort to deceit as in the United States asked for women with experience and willing to work. The reasoning is as follows: if women were deceived, they would deny to work, and the American bosses would not compensate Mexican polleros economically.

The coyotes I know take them there [United States] with experience, that is why they can’t be deceived because they are told where they go. (Ysmael).

They go because they want, that’s why they go and are not deceived, they told them what they go to, it is not convenient to deceive them because they don’t want to work and it is needed they work to pay the pollero (Zeferino).

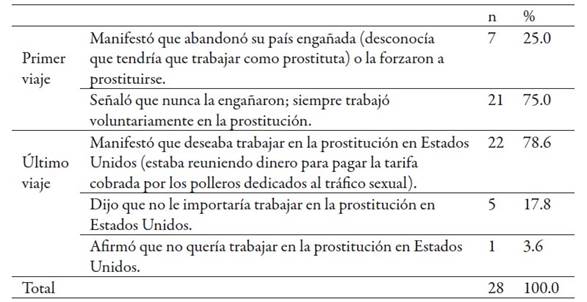

However, not all the women transported by sex trafficking networks are aware of the nature of the activity they will have to perform (Hua, 2011: 43 ). 25% of the interviewed Central American female migrants were introduced to sex industry by means of deceit or forced (see table 8). Some women are not told they will work in this industry until they reach the U.S. because if they were told they would not want to go. As Martín said: “there are women who are shy, they are offered the work there, in the U.S. […] Once there they are told there is no work where we had told them”.

As stated by Tamara: “they didn’t tell me before I went, but once I was there, what the fuck I would do? I was there, far from my family, with no money and I thought that work were men with no women for long and I had to please them sexually, I didn’t like the idea and I wanted to return, but they didn’t let me”.

Likewise, women voluntarily transported by sex trafficking networks are not usually aware of the labor conditions and wage they will find in the recipient country. 75% of the women interviewed would work in adult entertainment and 79% wanted to be transported to the U.S. by sex trafficking networks (see table 8), but ignored how much they will earn.

Zacarías, a pimp from Tamaulipas, Mexico, who worked in an adult entertainment center in Houston (Texas) between 1984 and 1994, stated:

They already knew what they went to, what they didn’t know is how much they will get paid, as in Mexico they are offered something and once in the U.S. they receive something else. Anyway it’s good money, but in that case they were deceived with the money. I’m telling you because sometimes I have to pay them and they tell me that they were told they would earn more.

Vicenta also said: “no one takes them, what happened to them is that they are told they will earn an amount of money and then they aren’t paid that, but less. That happens, they are deceived in the money they will earn”. Leandro pointed out: “the illegals make more money because in a certain way they don’t know their rights”.

Polleros recruited by drug cartels

The growth of organized crime in Mexico has made the networks that transport migrants complex. Some simple networks have merged to produce complex networks, in which there is labor division (Izcara-Palacios, 2014: 93 ). In these networks, the leader monitors the work of numerous polleros that are part of this network and negotiates with criminal groups the payment of a fee so that they can operate.

Recent research points out that criminal groups control the polleros; this way, the latter hold a lesser hierarchical position within a structure led by drug traffickers (Márquez Covarrubias, 2015: 161 ; Martínez et al., 2015: 134 ; Slack and Campbell, 2016: 16 ). Slack and Whiteford (2010: 90) state that “our interviews with some elements of the municipal police in Nogales, Sonora, make us conclude that those in command of the coyotes have allied with the narco”. However, this does not mean that “those in command of the coyotes” are part of the organized crime.

Juan, a pollero who worked in a network that hired dozens of coyotes, said that his leader had changed the route where they operated to avoid that criminal groups invited or seized their men. If that leader (who annually crossed several thousand migrants to the U.S.) was part of organized crime, he would not fear that their men would be recruited by criminal groups.

Because of that the boss made us change the place where we worked so that they [organized crime] would not invite us, because as the boss says: a missing man is one, but you don’t replace him easily, it is hard to find someone who wants to be a pollero, and more, some who knows and likes it.

Polleros are attractive for drug cartels, as they know the roads and paths at the border through which introduce drugs or bring weapons better than anyone (Izcara-Palacios, 2015: 331 ). As Miguel said: “the polleros they have taken have to show them the ways”. Frequently, criminal groups invite them to quit coyotaje and work for them. As indicated by Slack and Campbell (2016: 13 ), it is difficult to discern if the polleros who work for the organized crime do it voluntarily or forcedly. The most ambitious are lured by the high salaries.

Amadeo pointed out: “there are some who have gone with them [organized crime] because they offer more money and they are willing to receive more and go with them and help them. Regularly they are ordered to traffic drugs”. Although the juicy wages soon wane, once they enter these groups they cannot leave and have to settle with increasingly lower wages. Jorge commented the following case:

I knew one who left because he was offered a better wage, and he said they had told him he would be paid in dollars and decided to quit being a pollero; but I wasn’t as they said and when he stopped working for them they killed him and he was sent dismembered in a cooler to his relatives.

Polleros fear drug cartels. When they are elicited to become part of the organizations they generally decline the invitation. Benito said: “yeah they have insinuated something, but I don’t work for them, I only pay what they tell me”. Olga stated: “I was invited but I was very clear and said no”. However, most polleros cannot refuse the invitation to join the cartels.

As it is demonstrated in the following expression, frequently criminals approach the polleros with an intimidating tone and take them by force.

They [organized crime] have hired some [polleros] and use them, but it is because they threaten to kill them and their relatives, but not because they want to work with them but are forced to (Emilio).

They threaten to kill them and their families, that’s why they do it, and they prefer to work before anything bad happens (Esteban).

I know some who say: they threatened to kill my family and that’s why I work with them (Humberto).

Organized crime has taken polleros to work with them, but they are taken by force, not because they want (Martín).

Many polleros have been killed, others have been kidnapped and have been made to work for the organized crime (Miguel).

They have gone to work with them, but it is not willingly, but they are forced, they take them and they never return (Narciso).

Those who are threatened usually end up agreeing to the dictate of criminals, but there are also polleros who refuse to collaborate with them. As displayed in the following examples, some polleros would rather die than collaborate with the organized crime.

A friend from X, who took people, he told me that he was stopped and there they had another pollero and they were both told: you want to work for us or we kill you and we will send your heads to the families, and my friend told me that the other said yes, I’ll work for you, boss, I don’t wanna die, and he, my friend, answered them: I’d rather die than make bad things (Gerardo).

I told them I don’t want any fucking problem I have many already, and I’m chicken shit, and if they want to take I prefer to die to hurt people (Cosme).

Conclusion

Many polleros deceive migrants, rob them and do not take them where they agreed. Some of the respondents were not able to cross the border because their pollero ran away with their money. However, this is not how the networks that transport migrants operate.

Sex trafficking is a growing niche in coyotaje. Sex trafficking networks imply great risks as they operate with a certain degree of deceit. Polleros overrate the wages and do not inform the women about the long working hours nor the few days off.

However, the respondents said that most of the women moved by these network knew what they were taken for, they wanted to work in American adult entertainment centers and paid a high fee to be taken there. This was verified by most of the Central American women interviewed, even though a quarter of them was deceived or coerced. This research’s results also indicate that the women who worked in this industry and were deported soon came into contact with sex trafficking networks.

Furthermore, more and more polleros end up working for the organized crime. Some are lured by the easy money offered by drug cartels, but if they accept the invitation they are in great danger. When they are invited by the criminals, they try to hide from them, as they know that a negative might be fatal. Because of this, many of the polleros who join these groups are coerced. Moreover, the coyotes who join organized crime stop crossing migrants into the U.S.

In conclusion, polleros who deceive, rob and abandon migrants are an exception rather than a rule. The vulnerability of irregular migrants makes false polleros, some authorities and organized crime abuse them. The polleros who have exercised this activity for years normally take them to their destination. Migrants mistrust the coyotes who offer deals too attractive and look for those recommended by their friends or relatives. These are the strategies that they use to distinguish the good from the bad, albeit they think that the latter are the most numerous. Contrasting with the fear of detention by the authorities and the dread of organized crime, polleros are perceived by migrants as a lesser evil.

REFERENCES

Achilli, Luigi (2015), “The smuggler: Hero or felon?”, en Migration Policy Centre. Policy Briefs, núm. 2015/10, Italia: Migration Policy Centre. [ Links ]

Addiechi, Florencia (2005), Fronteras reales de la globalización. Estados Unidos ante la migración latinoamericana, México: UACM. [ Links ]

Agustín, Laura-María (2007), Sex at the margins.Migration, labour markets and the rescue industry, Estados Unidos: Zed Books. [ Links ]

Aquino-Moreschi, Alejandra (2012), “Cruzando la frontera: Experiencias desde los márgenes”, en Frontera Norte, vol. 24, núm. 47, México: Colegio de la Frontera Norte. [ Links ]

Cueva-Luna, Teresa Elizabeth y Terrón-Caro, Teresa (2014), “Vulnerabilidad de las mujeres migrantes en el cruce clandestino por Tamaulipas-Texas”, en Papeles de Población, vol. 20, núm. 79, México: Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México. [ Links ]

Díaz-González, Eliseo (2009), “Riesgo moral y transmisión de señales: Análisis de la relación del pollero-mojado en una perspectiva microeconómica”, en Ra Ximhai, vol. 5, núm. 1, México: Universidad Autónoma Indígena de México. [ Links ]

Doezema, Jo (2010), Sex slaves and discourse masters. The construction of trafficking, Estados Unidos: Zed Books. [ Links ]

Feldmann, Andreas y Durand, Jorge (2008), “Mortandad en la frontera”, en Migración y Desarrollo, núm. 10, México: Red Internacional de Migración y Desarrollo. [ Links ]

Fuentes, Jezmín y García, Olivia (2009), “Coyotaje: The Structure and Functioning of the People-Smuggling Industry”, en Cornelius, Wayne A., Fitzgerald, David y Borger, Scott [eds. ], Four generations of norteños. New Research from the Cradle of Mexican Migration, Estados Unidos: Centre for Comparative Immigration Studies. [ Links ]

García-Vázquez, Nancy et al. (2007), “Movimientos transfronterizos México- Estados Unidos: Los polleros como agentes de movilidad”, en Confines de Relaciones Internacionales y Ciencia Política, vol. 3, núm. 5, México: Tecnológico de Monterrey. [ Links ]

Guerette, Rob y Clarke, Ronald (2005), “Border Enforcement, Organized Crime, and Deaths of Smuggled Migrants on the United States-Mexico Border”, en European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, núm. 11, Estados Unidos: Springer International Publishing. [ Links ]

HCHS (House Committee on Homeland Security) (2006), A Line in the Sand: Confronting the Threat at the Southwest Border, Subcommittee on Investigations. Estados Unidos: House Committee on Homeland Security. [ Links ]

Hua, Julietta (2011), Tafficking women’s human rights, Estados Unidos: University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Izcara-Palacios, Simón (2014), “La contracción de las redes de contrabando de migrantes en México”, en Revista de Estudios Sociales, núm. 48, Colombia: Universidad de los Andes. [ Links ]

Izcara-Palacios, Simón (2015), “Coyotaje and drugs: Two different businesses”, en Bulletin of Latin American Research, vol. 34, núm. 3, Inglaterra: Wiley. [ Links ]

Izcara-Palacios, Simón (2016), “Violencia postestructural: migrantes centroamericanos y cárteles de la droga en México”, en Revista de Estudios Sociales, núm. 56, Colombia: Universidad de los Andes. [ Links ]

Kimball, Ann et al. (2007), “Impacts of US Immigration Policies on Migration Behavior”, en Cornelius, Wayne A. et al. [eds. ], Mayan Journeys: The New Migration from Yucatán to the United States, Estados Unidos: Center for Comparative Immigration Studies, University of California. [ Links ]

Kyle, David y Scarcelli, Marc (2009), “Migrant smuggling and the violence question: evolving illicit migration markets for Cuban and Haitian refugees”, en Crime, Law and Social Change, vol. 52, núm. 3, Estados Unidos: Springer. [ Links ]

Lim, Timothy C. (2014), “Migrant Korean women in the US commercial sex industry: an examination of the causes and dynamics of cross-border sexual exploitation”, en Journal of Research in Gender Studies, vol. 4, núm. 1, Estados Unidos: Addleton Academic Publishers. [ Links ]

Márquez-Covarrubias, Humberto (2015), "No vale nada la vida: éxodo y criminalización de migrantes centroamericanos en México", en Migración y desarrollo, vol. 13, núm. 25, México: Red Internacional de Migración y Desarrollo. [ Links ]

Martínez, Daniel E. (2016), “Coyote use in an era of heightened border enforcement: New evidence from the Arizona-Sonora border”, en Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, vol. 42, núm. 1, Estados Unidos: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. [ Links ]

Martínez, Graciela et al. (2015), “Trazando rutas de la migración de tránsito irregular o no documentada por México”, en Perfiles latinoamericanos, vol. 23, núm. 45, México: FLACSO. [ Links ]

Nevins, Joseph (2003), “Thinking out of bounds: A critical analysis of academic and human rights writings on migrant deaths in the U.S.-Mexico border region”, en Migraciones Internacionales, vol. 2, núm. 2, México: El Colegio de la Frontera Norte. [ Links ]

Parks, Kristen et al. (2009), “Strategies for success: Border crossing in an era of heightened security”, en Cornelius, Wayne A. et al. [eds. ], Migration from the Mexican Mixteca. A transnational community in Oaxaca and California, Estados Unidos: Centre for Comparative Immigration Studies. [ Links ]

Sánchez, Gabriella (2015), “Human smuggling facilitators in the US Southwest”, en Pickering, Sharon y Ham, Julie [comps. ], The Routledge Handbook on Crime and International Migration, Estados Unidos: Routledge. [ Links ]

Sánchez, Gabriella (2016), “Women’s Participation in the Facilitation of Human Smuggling: The Case of the US Southwest”, en Geopolitics, vol. 21, núm. 2, Estados Unidos: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. [ Links ]

Sharma, N. (2003), “Travel Agency: A Critique of Anti-Trafficking Campaigns”, en Refuge, vol. 21, núm. 3, Canadá: Centre for Refugee Studies at York University. [ Links ]

Slack, Jeremy y Whiteford, Scott (2010), “Viajes violentos: La transformación de la migración clandestina hacia Sonora y California”, en Norteamérica, vol. 5, núm. 2, México: UNAM. [ Links ]

Slack, Jeremy (2016), “Captive bodies: migrant kidnapping and deportation in Mexico”, en Area, vol. 48, núm. 3, Estados Unidos: Wiley. [ Links ]

Slack, Jeremy y Campbell, Howard (2016), "On Narco-coyotaje: Illicit Regimes and Their Impacts on the US-Mexico Border", en Antipode, vol. 48, núm. 5, Estados Unidos: Wiley. [ Links ]

Slack, Jeremy et al. (2016), “The Geography of Border Militarization: Violence, Death and Health in Mexico and the United States”, en Journal of Latin American Geography, vol. 15, núm. 1, Estados Unidos: Elsevier. [ Links ]

Spener, David (2004), “Mexican Migrant-Smuggling: A Cross-Border Cottage Industry”, en Journal of International Migration and Integration, vol. 5, núm. 3, Holanda: Springer Netherlands. [ Links ]

Spener, David (2009), Clandestine Crossings: Migrants and Coyotes on the Texas- Mexico Border, Estados Unidos: Cornwell University Press. [ Links ]

Spener, David (2011), “Global Apartheid, Coyotaje, and the Discourse of Clandestine Migration. Distinctions between Personal, Structural and Cultural Violence”, en Kyle, David y Kolowski, Rey, Global Human Smuggling. Comparative Perspectives, Estados Unidos: The Johns Hopkins Press. [ Links ]

Thompson, Albert (1956), “The Mexican Immigrant Worker in Southwestern Agriculture”, en American Journal of Economics and Sociology, vol. 16, núm. 1, Estados Unidos: Wiley. [ Links ]

Weitzer, Ronald (2015), “Human trafficking and contemporary slavery”, en Annual Review of Sociology, vol. 41, Estados Unidos: JSTOR. [ Links ]

Zhang, Sheldon et al. (2007), “Women’s participation in Chinese Transnational Human Smuggling: A gendered market perspective”, en Criminology, vol. 45, núm. 3, Estados Unidos: Wiley . [ Links ]

4The respondents were stranded in Mexico owing to some reason (they were robbed, did no have enough money to cross, the smuggler cheated on them, were kidnapped, etc.).

Received: August 24, 2015; Accepted: September 21, 2016

texto en

texto en