INTRODUCTION

The leather industry has been categorized as highly polluting, raising concerns about its potential adverse environmental impact, despite its significant global sales and high commercial value (Viteri et al. 2017, Bekele and Ramaiah 2023). Leather production remains a major contributor to environmental pollution due to the generation of substantial by-products and waste. Improper management of these wastes can negatively impact human health and degrade environmental quality (Vallejo et al. 2019, Islam et al. 2022).

Approximately 90% of raw leather worldwide is tanned using basic chromium sulfate in manufacturing processes (Cabeza et al. 1998, Vásquez et al. 2020). Known as chrome tanning, this method offers numerous advantages in the tannery industry: it is cost-effective, readily available, and versatile (Vásquez et al. 2020), providing excellent cross-linking properties (Hashmi et al. 2017, Scaraffuni et al. 2020). Leather tanned with chromium compounds exhibits superior physical and chemical properties. In traditional leather manufacturing, between 8 and 12% of basic chromium sulfate (BCS) is used relative to the weight of wet leather (Mottalib et al. 2023, Rosiati et al. 2024). Of this percentage, 60 to 70% reacts with collagen fibers to form leather, while the remaining 30 to 40% of BCS does not react and ends up as waste, released as untreated toxic effluents from leather industries (Vallejo et al. 2019, Scaraffuni et al. 2020). Considerable knowledge has accumulated on alternatives to chrome tanning and management practices in the leather subsector in developed countries. However, there are few reports on the implementation of these ecological techniques in tanneries in developing countries (Oruko et al. 2020). Waste management in these countries typically involves collection, storage, and transportation to landfills by public utility companies (Kanagaraj et al. 2006, Flores et al. 2023).

Strict protocols are crucial during temporary storage and transport to prevent contamination and ensure unobstructed access routes. Final disposal of the waste occurs on a quarterly basis to prevent excessive accumulation. While these practices are responsible, they are insufficient to fully mitigate environmental impact. Therefore, continuous improvement of these practices and exploration of new alternatives are essential to making significant contributions to environmental conservation and community health (Zúñiga et al. 2021).

The tanning industry is primarily composed of small and medium-sized enterprises. Globally, leather is one of the most traded products, with an estimated annual value of around USD 100 billion. The demand for leather and its derivatives is expected to continue outpacing supply growth, posing challenges for both development and waste management (Oruko et al. 2020).

Leather production generates liquid, gaseous, and solid waste, and involves various chemicals, including lime, sodium sulfide, ammonium sulfate, sodium chloride, chromium salts, tannins, and bactericides. During leather production, wet blue shavings are obtained, representing an average of 25% of the total production weight. These shavings consist of approximately 4.3% chromium oxide (Cr2O3) and 14.5% nitrogen (N), as determined by the Kjeldahl analysis method, along with 16.7% total ash at 600 ºC and 0.8% fat. The moisture content of the shavings ranges from 55 to 60% of the weight of dry shavings (Schneider et al. 2013).

Globally, liquid and solid wastes generated in tanneries include chemical oxygen demand (COD) of 1470 mg/L, biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) of 619 mg/L, suspended solids of 920 mg/L, chromium of 30 mg/L, sulfur of 60 mg/L, and solid wastes totaling 3000 t (Magalhães et al. 2023).

In Arequipa, approximately 7963.734 kg of wet blue shavings are generated annually, equivalent to about 7964 t of this waste (Onem and Bozkurt 2022). A tannery processing 5000 hides produces approximately 12 t of shavings (Ozgunay et al. 2007). Proper management of these shavings, which are mainly composed of high concentrations of collagen and chromium in their chemical composition (Viteri and Valle 2015), is essential under current national legislation, entailing additional costs and posing an unresolved challenge (Gendaszewska et al. 2024). Collagen from shavings can be processed into various useful products, extending benefits beyond the leather sector. The primary challenge for tanneries is to add value to their waste (Butrón and Katime 2014).

Various studies have demonstrated that modifying factors such as pH, moisture, and particle size is crucial for manufacturing new materials from wet blue shavings, with applications across industries including plastics, construction, chemicals, textiles, and synthetic leather (Mollehuanca et al. 2023). Particularly in the leather industry, resin, a thermosetting polymer, has become an essential component due to its heat and solvent resistance, making it ideal for creating synthetic leather and offering a durable and versatile alternative to natural leather (Aguas et al. 2016).

This research proposes an alternative approach to creating a composite material (reconstituted leather) utilizing leather shavings waste as a reinforcement material and a thermoplastic resin as the polymer matrix.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

Solid waste (leather shavings) was kindly donated by the company Pieles del Sur. Different resins used, such as Addix E15, technically named transparent acrylic emulsion/concentrate, and Vinnapas 401 resin, technically named vinyl acetate-ethylene stabilized with poly (vinyl alcohol), along with other inputs and chemical materials, were supplied by the laboratory of the Institute of Engineering, Energy, and Environment (IIEM) at Universidad Católica San Pablo (UCSP).

Methods

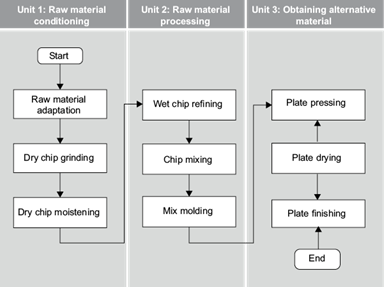

For this research, an experimental methodology was proposed based on the design and development of a process that utilizes tannery waste to obtain an alternative material. This process consists of three units: The first unit involves raw material conditioning, starting with the preparation of the shavings up to moistening; the second unit covers raw material processing, encompassing refining to the molding of the mixture; and finally, the third unit focuses on obtaining the alternative material, ranging from pressing to finishing reconstituted leather sheets. The process is complemented by an experimental model that details materials, characteristics, and parameters at each process unit, along with statistical analysis of tests conducted, a factorial design, and ultimately, a cost-benefit economic analysis of materials for the alternative material product.

Design and development of the process

To design the process (Fig. 1), the following criteria were considered: leather shavings must be sourced from a local tannery to ensure durability and suitability for the project. The resin underwent two types of evaluations: qualitative and technical. The technical evaluation was conducted in a laboratory to determine key aspects for producing reconstituted leather sheets, including identifying the type of resin, establishing optimal operational parameters for shavings, resin, and water percentages, and determining the appropriate shavings size. This was done to meet established parameters for each process unit, such as color, size, acidity level, strength, flexibility, and fracture resistance. Qualitative characteristics considered for resin selection included product accessibility and regulatory compliance, accident or incident risks, ease of use, eco-friendliness, storage conditions, and water reaction. Resins meeting qualitative criteria were further evaluated for technical characteristics through laboratory tests simulating the initial process units: conditioning and raw material processing. Key factors considered during mixing included adhesion to leather shavings, sensory viscosity, and mix cohesion.

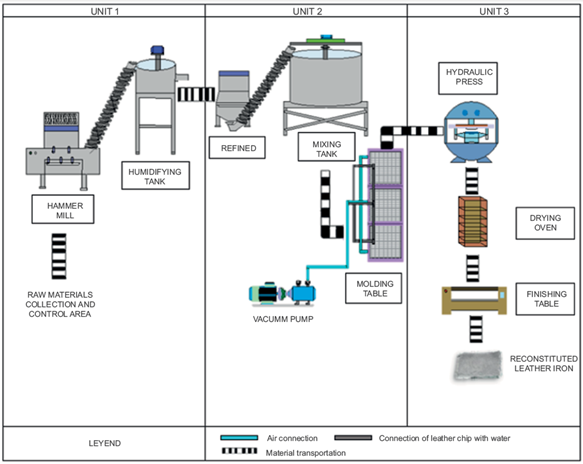

Experimental model

The design and development of the process were considered essential for the development of the experimental model (Fig. 2), which consists of a series of custom-made equipment for carrying out operations on a continuous pilot line (Fig. 3). This allowed the process to be optimized in terms of time and waste management for the development of the reconstituted leather production process.

Unit 1. Raw material conditioning

This unit aims to ensure that leather shavings possess the necessary chemical and physical characteristics, such as decomposition, size, and color, to initiate the production process. This process involves activities such as receiving, storing, verifying, and weighing the collected shavings.

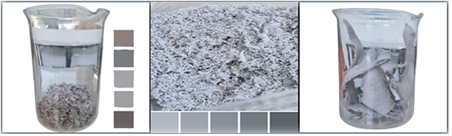

Initially, the shavings are taken to the UCSP Process Improvement and Pilot Testing Laboratory, where they are unloaded and temporarily stored at room temperature to avoid exposure to high temperatures, which could accelerate their decomposition. Upon receiving and storing the shavings, a sensory test is conducted. During this test, the color of the shavings is compared to the Pantone color chart (Fig. 4) to determine if the sample shows signs of rot or if it is wet or dry. Following this sensory verification, the selected shavings are transported for the grinding operation.

Grinding of the shavings lasts approximately one hour, during which the size of the shavings is reduced. If the ground leather shavings are smaller than 0.02 in or larger than 0.75 in, they will be discarded, as this will result in sheets that are less resistant to tearing. After grinding, dry shavings of the specified size are obtained by passing them through the employed sieve.

Next, the ground shavings are transported to a moistening tank via a conveyor belt, where water is added to obtain moist shavings. This prevents overheating of the refiner and ensures proper fiber suspension during subsequent shearing and friction processes. The shavings should have a moisture content of between 40% and 60%. In the refining process, the fiber size is reduced to achieve the desired tensile strength and elongation properties in the final product. During this process, a sample is taken to control acidity levels, ensuring that the pH is between 3.5 and 5, as maintaining this acidity range is crucial to ensuring the quality of the product obtained.

Finally, after the refining process, refined dry shavings are produced and are ready for use in the production of reconstituted leather sheets. Thanks to the design and development of the process in the continuous line pilot plant, no material is left unused, achieving a waste-free process and optimizing the process in its entirety.

Unit 2. Raw material processing

Once the refined shavings are obtained, they are transported using a screw conveyor to the mixing tank to ensure uniform distribution. Initially, water and binder (resin) are added in varying proportions, with a range of 5 to 95% for both water and binder relative to the total mixture being evaluated. This mixture is stirred for at least 3 min to ensure proper integration of the components. Thanks to preliminary tests, it has been proven that mixing for less than 3 min results in incomplete integration of the resin, water, and shavings, leading to a poor mixture. Additionally, exceeding 5 min of mixing does not yield any noticeable improvement in the consistency of the mixture.

After mixing, the pH of the mixture is measured, which should be maintained within the range of 3.5 to 5. Previous experiments with varying pH levels demonstrated that a pH lower than 3.5 is excessively acidic and could accelerate the oxidation of chromium III, affecting the mechanical properties of the sheet. Conversely, a pH above 5 is considered basic and can also negatively influence the quality of the final product.

In the molding stage, the mixture is poured onto molding tables, and excess water is removed using a vacuum pump without losing solids, resulting in sheets with a moldable consistency and the necessary dimensions (297 × 420 mm). Subsequently, the thickness is standardized in the same glass mold, and the sheets are left to dry, forming the final sheets with dimensions of 297 × 420 mm (Fig. 5).

Unit 3. Alternative material acquisition

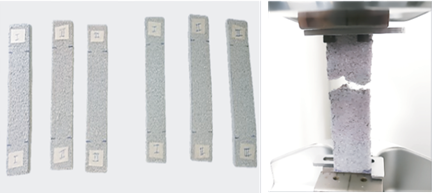

The molded sheet is placed in a hydraulic press, where pressure is applied varying between 400, 800, and 1200 psi, revealing that pressures exceeding 800 psi deteriorate the fibers (Fig. 6). Intervals of 10, 15, and 20 min are tested to evaluate their impact. This action determines the desired final thickness and consistency of the sheet, with the primary parameters to consider in this stage being the applied pressure and the final thickness of the sheet. After pressing, the sheet is transferred to the drying process, where the goal is to completely remove excess water particles. Stainless steel trays are used for this purpose, where the compact sheets from the previous stage are placed. A combination of time and temperature is used through air drying to prevent the binder from melting. The final product must meet certain quality standards, including tests for tensile strength, tear resistance, and end elongation at break. Upon completing this stage, the reconstituted leather sheet (Fig. 7) will undergo finishing processes according to the customer’s requirements.

MECHANICAL PROPERTIES

Mechanical properties were evaluated before implementing a 2k factorial design using previous values to analyze the influence of temperature and pressing time. With the selected variables, Statgraphics was used to determine 16 scenarios, each with 3 replicates, and the mean values of chip sizes (3.81 mm) were taken to validate the mathematical modeling. The selected samples were cut to dimensions of 13 cm in length and 2.5 cm in width to obtain specimens for conducting tensile tests. This procedure enabled the collection of data on maximum breaking stress.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

For the design and development of the resin identification process, Addix and Vinnapas were utilized and selected based on an analysis and evaluation of their characteristics. The effect of these characteristics on the material production process was determined and summarized in a comparative table (Table I). It is important to highlight that, in both cases, a percentage of 10% of shavings was maintained, since it gave the best results, and as a primary raw material, shavings were the priority.

TABLE I RESIN COMPARISON.

| Characteristics | Vinnapas resin | Addix resin |

| Mix cohesion | Lower with higher resin quantities | Lower with higher shaving quantities |

| Behavior with increasing resin percentage | Lower cohesion of the mixture | Better results, greater fluidity |

| Economic scenario (resin percentage) | 35% | 35% |

| Expensive scenario (resin percentage) | 45% | 65% |

| Best results with meshes | Meshes 1 and 6 | Meshes 1, 2, and 3 (with emphasis on mesh 3) |

In the experimental model for the conditioning unit in the leather shavings grinding process, results from mill-type selection tests revealed six sieves ranging in size from 0.05 to 0.3 in. It was determined that shavings processed through sieves larger than 0.3 in did not show significant changes during grinding. Each sieve was assigned an identification number to facilitate its use in the process. The use of the knife mill yielded good results in terms of cohesion and sheet formation; however, tests with the hammer mill presented significant challenges in sheet formation, particularly when using a shavings percentage above 10%, proving less effective in ensuring mixture cohesion and proper sheet formation at higher shavings levels. In the mixing unit, 72 tests were conducted to determine the optimal proportions of mix components: leather shavings between 5 and 80%, resin between 5 and 50%, and water between 0 and 80%. The calculation basis was a total mix of 65 g, adjusted for the amount of water to complete the total weight. During this stage, difficulties arose, requiring the application of external force. Additionally, at the end of mixing, dry shavings residue was found at the bottom of the container, indicating incomplete blending of shavings, resin, and water. This led to the decision to discard the use of shavings percentages exceeding 25%. Furthermore, water, as an addition to the mixture of shavings and resin, was set at a minimum of 5% (Table II). The presence of water is crucial for the fluidity of the mixture; without it, filtering is not possible, and the sheet cannot form correctly. Following the laboratory-level testing, the mapping of optimal operating ranges was developed (Table III). In the alternative material acquisition unit for drying sheets, temperatures of 35, 50, and 65 ºC were applied for Vinnapas resin, as beyond 80 ºC the resin becomes too viscous, affecting its agglomeration ability. Conversely, no heat was applied to Addix, as exposure to high temperatures forms a surface layer, resulting in a fragile, bubbly sheet. During the drying phase, sheets made with Vinnapas were subjected to 130 ºC to soften their structure and prevent damage during pressing, while those made with Addix were dried at 50 ºC due to the resin’s thermal properties.

TABLE II COMPOSITION PARAMETERS AND APPROPRIATE RANGE FOR MIXING AND FILTERING.

| Component | Appropriate range | Observations |

| Leather shavings | 5-10% | Values above 10% make mixing difficult |

| Resin | 35-65% | Values above 65% complicate filtering and exceed the mold |

| Water | 25- 65% | - |

| Acidity level | 4-5 | Constant in all cases |

TABLE III MATERIAL COMPOSITION RANGES DURING THE PROCESS.

| Inputs | Start of stage (%) | End of stage (%) |

| Leather shavings | 5-25 | 5-25 |

| Resin | 5-95 | 5-50 |

| Water | 5-90 | 30-55 |

In the tensile tests, the study results revealed two clear trends (Table IV). On one hand, scenarios with high strength were characterized by combining high pressure (1200 psi), a constant temperature of 35 ºC, and a moderate percentage of water (20%). On the other hand, scenarios with low strength shared the use of smaller chip sizes (2.54 mm) and higher percentages of water (65%), though not always the same pressure or pressing time.

TABLE IV TEST SCENARIOS AND MAXIMUM STRESSES.

| Scenario | Leather shavings size (mm) | Shavings/Resin (% W/W) | Water (%) | Temperature (ºC) | Pressure (PSI) | Pressing time (min) | Average maximum stresses |

| 1 | 2.54 | 25 | 20 | 35 | 400 | 10 | 1.856 |

| 2 | 5.08 | 25 | 20 | 35 | 1200 | 10 | 1.474 |

| 3 | 2.54 | 35 | 20 | 35 | 1200 | 20 | 0.129 |

| 4 | 5.08 | 35 | 20 | 35 | 400 | 20 | 0.471 |

| 5 | 2.54 | 25 | 30 | 35 | 1200 | 20 | 1.061 |

| 6 | 5.08 | 25 | 30 | 35 | 400 | 20 | 1.146 |

| 7 | 2.54 | 35 | 30 | 35 | 400 | 10 | 0.147 |

| 8 | 5.08 | 35 | 30 | 35 | 1200 | 10 | 0.319 |

| 9 | 2.54 | 25 | 20 | 65 | 400 | 20 | 1.199 |

| 10 | 5.08 | 25 | 20 | 65 | 1200 | 20 | 1.971 |

| 11 | 2.54 | 35 | 20 | 65 | 1200 | 10 | 0.123 |

| 12 | 5.08 | 35 | 20 | 65 | 400 | 10 | 0.373 |

| 13 | 2.54 | 25 | 30 | 65 | 1200 | 10 | 0.415 |

| 14 | 5.08 | 25 | 30 | 65 | 400 | 10 | 1.427 |

| 15 | 2.54 | 35 | 30 | 65 | 400 | 20 | 0.172 |

| 16 | 5.08 | 35 | 30 | 65 | 1200 | 20 | 0.241 |

| 17 | 3.81 | 30 | 25 | 50 | 800 | 15 | 1.165 |

| 18 | 3.81 | 30 | 25 | 50 | 800 | 15 | 1.133 |

| 19 | 3.81 | 30 | 25 | 50 | 800 | 15 | 0.843 |

When compared with the reconstituted leather processing methods described in the patent by Young et al. (1963), which employ moderate pressure and controlled moisture to enhance the cohesion of recycled leather fibers, it is observed that high pressure combined with stable moisture conditions increases the mechanical strength of the compounds. Similarly, Dimiter’s (1981) patent proposes an approach that optimizes leather flexibility by elastomerizing fine particles and forming aggregates, thereby enhancing impact resistance even at low temperatures. This contrasts with the findings in this study for larger chips and higher water content, where strength was significantly reduced.

On the other hand, the study conducted by Flores et al. (2013) explores the production of an adhesive derived from the hydrolysis of leather shavings, utilizing temperatures close to the boiling point to break collagen bonds and thereby maximize adhesive strength. In this process, a ratio between wood shavings and adhesive is employed, based on previous studies using leather shavings as filler and the same adhesive under standardized drying conditions (90 ºC for 24 h). The results from tensile tests indicate a significant average tensile strength of 2 647 835 N/m2, while moisture control during drying helps minimize deformations, thus enhancing the dimensional stability of the final composite. Furthermore, the study concludes that the fabricated material exhibits satisfactory mechanical characteristics, both in terms of tensile strength and dimensional stability.

This study contributes new insights by demonstrating how the combination of high pressure and precise moisture control can optimize the mechanical performance of leather waste-based compounds, thereby supporting the development of sustainable materials for applications in construction and manufacturing.

Economic analysis

The production costs for reconstituted leather sheets were analyzed (Table VIII), considering only the cost of inputs, mainly the resins, since the leather shavings, being waste, have no market cost. Two sensitivity analysis scenarios were proposed based on the best test results. The first scenario (Table V) corresponds to the highest percentages of Addix and Vinnapas resins at 65 and 45%, respectively. In comparison, the second scenario (Table VI) involves a lower percentage of 35% for both resins. Both resins demonstrated market competitiveness; however, Vinnapas not only aligns better with the economic option but also offers a viable strategy to optimize production and maximize profits.

TABLE V COMPOSITION PARAMETERS AND APPROPRIATE RANGE FOR MIXING AND FILTERING IN THE EXPENSIVE SCENARIO.

| Inputs | Density (kg/m3) | Higher cost (%) | Weight for one sheet of 21 × 15 (kg) | Volume (m3) | Weight for one sheet of 21 × 29.7 (kg) | |||

| Water | 997 | 25 | 45 | 0.25 | 0.45 | - | 0.5 | 0.9 |

| Leather shavings | - | 10 | 10 | 0.1 | 0.1 | - | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Addix | 1003.87 | 65 | - | 0.65 | - | 0.0006475 | 1.3 | - |

| Vinnapas | 1050 | - | 45 | - | 0.45 | 0.0004286 | - | 0.9 |

TABLE VI COMPOSITION PARAMETERS AND APPROPRIATE RANGE FOR MIXING AND FILTERING IN THE ECONOMIC SCENARIO.

| Inputs | Density (kg/m3) | Higher cost (%) | Weight for one sheet of 21 × 15 (kg) | Volume (m3) | Weight for one sheet of 21 × 29.7 (kg) | |||

| Water | 997 | 55 | 55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | - | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| Leather Shavings | - | 10 | 10 | 0.1 | 0.1 | - | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Addix | 1003.87 | 35 | - | 0.35 | - | 0.0003487 | 0.7 | - |

| Vinnapas | 1050 | - | 35 | - | 0.35 | 0.0003333 | - | 0.7 |

A resin cost table was created for both scenarios (Table VII) to detail the specific inputs in each scenario and provide a comparative analysis of the resin costs used. It is important to highlight that cost calculations were made on a per-unit basis, specifically for a 21 × 297 cm sheet, not by batch. Finally, using the national market price for leather, which is sold by the square foot (30.48 × 30.48 cm), the cost was approximated per sheet, which is our production unit.

TABLE VII VARIABLE COST PER SHEET.

| Addix (S/) | Vinnapas (S/) | |

| Variable cost per plate | 11.00 | 12.50 |

| Variable cost per one plate of 21 × 29.7 (most expensive scenario) | 14.30 | 11.25 |

| Variable cost per one sheet of 21 × 29.7 (most economical scenario) | 7.70 | 8.75 |

S/: Peruvian soles.

TABLE VIII COST COMPARISON.

| Material | Dimensions | Profit margin (%) | Sale price per sheet (S/) | Production cost per sheet (S/) | ||||

| Length (cm) | Width (cm) | Area (cm2) | Addix | Vinnapas | Addix | Vinnapas | ||

| Reconstituted leather sheet | 21 | 29.7 | 623.7 | 20 | 17.6 | 13.50 | 14.30 | 11.25 |

| 20 | 9.24 | 10.50 | 7.7 | 8.75 | ||||

| Leather sheet | 30.48 | 30.48 | 929.03 | 20 | 15 | 10.07 | 8.39 | |

S/: Peruvian soles.

CONCLUSION

The tanning industry in Arequipa generates a large amount of waste. For example, from a 38 kg hide, approximately 24 kg of waste is produced, including around 3.96 kg of “wet blue” shavings. This specific waste, which resembles steel shavings in appearance, is mainly composed of collagen and chromium (Cr2O3 between 4.3 and 4.5%), making it potentially toxic. Despite this, it has properties such as low thermal conductivity and adhesive power, suggesting that it could be reusable, unlike other waste materials like hair or meat scraps. Currently, tanneries pay to dispose of “wet blue” shavings and other solid waste in landfills, which generates additional costs. This process does not constitute true waste management, but merely disposal.

A sustainable process was designed to utilize wet blue shavings, consisting of three units that enable the continuous use of local tannery leather waste to obtain an alternative material, utilizing three main inputs: leather shavings, resins, and water. The resulting material exhibits notable characteristics, such as high impact resistance even at low temperatures and remarkable crack resistance, derived from the comparative analysis of results presented in the patents by Young et al. (1963) and Dimiter (1981). When compared with the reconstituted leather processing methods described in these patents, it is observed that high pressure combined with stable moisture conditions increases the mechanical strength of the compounds.

The experimental model employed the following equipment: a hammer/knife mill, conveyor belt, and humidifying tank in the conditioning unit; a refiner with an auger conveyor, mixing tank, molding table, and vacuum pump in the processing unit; and finally, a hydraulic press and dryer in the material acquisition unit. Through qualitative and technical evaluations, Addix E15 and Vinnapas 400 resins were successfully identified, determining the optimal proportion to be between 35% and 65%. Tests demonstrated that using the hammer mill, compared to the knife mill, resulted in greater consistency and better results in terms of mixture cohesion, sheet formation, and fracture resistance.

For better performance in tensile tests, the chip-to-resin ratio is the most influential variable. Another variable to consider about tension is chip size, with mesh 4 (5.08 mm) being recommended. Although pressure and pressing time are not determining factors for tensile strength, they can improve the finish.

Finally, the economic analysis showed that Vinnapas resin is the most cost-effective and functional option compared to Addix resin. The comparison between the two sensitivity scenarios reveals that, although both resins allow for market competition, Vinnapas is better suited to the company’s economic objectives. When analyzing the costs per production unit (21 × 29.7 cm sheets), it is evident that the financial scenario reduces the cost per sheet compared to the expensive scenario, allowing for more favorable profit margins (20%). The ideal resin for production and sale would be Vinnapas, as at its minimum acceptable concentration of 35%, it presents a competitive cost and is close to the optimal percentage of 45% obtained in the tests.

Throughout the process, no waste was generated, as the entire material was utilized, maximizing the process’s efficiency and preventing the creation of additional waste.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)