Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Frontera norte

versión On-line ISSN 2594-0260versión impresa ISSN 0187-7372

Frontera norte vol.37 México ene./dic. 2025 Epub 25-Abr-2025

https://doi.org/10.33679/rfn.v1i1.2426

Article

Tijuana White: Drugs, Culture and Despair in the Fentanyl Era

1El Colegio de la Frontera Norte (https://ror.org/04hft8h57), ralmed@colef.mx

2Universidad Autónoma de Baja California (https://ror.org/05xwcq167), jaime.rivas@uabc.edu.mx

This paper addresses the relationships between drugs and culture in the fentanyl era in the city of Tijuana, on Mexico’s northern border, based on a review of newspapers, an analysis of governmental videos on addiction prevention, and ethnographic material. Drawing on the work of Michel Aglietta and others, we propose the existence of an addiction regime that (re)produces discourses on substance use and its institutional treatment, generating a contentious language regulating the forms of signification around drugs, and the diverse fashions in which the state manages populations involved in the drug economy, particularly in social contexts where structural conditions of despair prevail.

Keywords: drugs and drug addiction; culture and society; drug control; borders; social inequality

Este artículo aborda la relación entre drogas y cultura en la era del fentanilo en Tijuana, ciudad fronteriza del norte de México. La metodología se sustenta en una revisión hemerográfica, el análisis de videos gubernamentales de prevención de adicciones, así como en material etnográfico. A partir de los trabajos de Michel Aglietta, entre otros, se propone la existencia de un régimen de adicción que (re)produce discursos en torno al consumo de sustancias y su tratamiento institucional, generando un lenguaje contencioso que regula las formas de significación en torno a las drogas y los modos diferenciados en que el Estado administra poblaciones implicadas en la economía del tráfico, particularmente en contextos sociales donde imperan condiciones estructurales de desesperación.

Palabras clave: drogas y toxicomanías; cultura y sociedad; control de drogas; fronteras; desigualdad social

INTRODUCTION

The relationship between humans and drugs dates back to the dawn of civilization. Archaeological evidence suggests that substance use and abuse were present in the earliest human settlements and city-states. The consumption of alcoholic substances is as ancient as the origins of Egyptian civilization, where beer played a significant role in both daily life and religious rituals. Excessive drinking was even glorified, with some accounts describing individuals inducing vomiting to continue consuming more. In ancient Persia, rulers discussed political matters twice—once sober and once intoxicated—believing that this practice fostered honesty among participants (Forsyth, 2019).

However, alcohol consumption was often regulated by social class, with access to different types and qualities of alcohol varying based on status. In pre-Hispanic Mexico, the consumption of pulque was largely reserved for the ruling elite, particularly in ritual contexts and among the priestly caste. While the elderly were allowed to drink it, its use among young people was strictly punished. The same restrictions applied to psychoactive substances—such as various mushrooms and other medicinal or ritualistic herbs—used by different Indigenous groups for healing and religious ceremonies (Grisel, 2019). Beyond the Americas, the use of opium dates back to the earliest known civilizations. In ancient Mesopotamian cities, its relaxing, anesthetic, and antidiarrheal properties were already well understood. Additionally, its recreational effects were widely recognized and valued (Halpern & Blistein, 2019).

The relationship between humans and their preferred drugs is both ancient and complex. This study does not aim to provide a detailed history—nor even a broad outline—of the millennia of substance use across different geographical contexts. Rather, it seeks to emphasize that understanding the contentious relationship between humans and drugs requires recognizing the intricate role these substances have played over time. It is essential not only to consider the individual consumption of substances but also to examine their role in shaping diverse cultural experiences and structuring geopolitical orders across various spatial and temporal scales (Gootenberg, 2022). It is at the intersection of individual experience, culture, and power that what is referred to here as addiction regimes emerge. These regimes extend beyond individual responsibility for drug consumption; they encompass the construction of a shared perspective on drug use, from which a network of symbols and meanings is created. This shared framework sustains a political-economic order that transforms substance use into a mechanism for unlimited rent extraction.

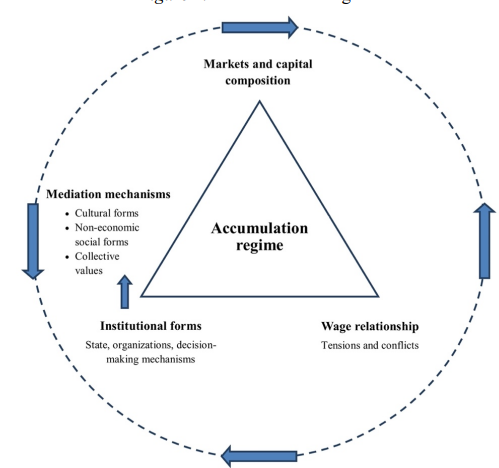

An addiction regime is a system of power built around the production, distribution, and consumption of one or more addictive substances (e.g., tobacco, alcohol, opioids, stimulants, hallucinogens, sweeteners). This regime not only regulates economic participation in the value chain but also shapes cultural dynamics. Like any regulatory system, it defines how individuals engage socioeconomically and politically in the creation of a commodity, its distribution and consumption patterns, and the unequal distribution of the profits it generates. Moreover, it produces layered and interconnected spatial-temporal formations that link various institutional structures. As Aglietta (2001, p. 19) explains, “A mode of regulation is a set of mediations that ensure the distortions created by capital accumulation remain within limits compatible with social cohesion within each nation” (Figure 1).

Within the analytical framework outlined in Figure 1, the addiction regime operates as a subsystem within the broader regime of accumulation (Boyer, 1990). It serves as a mediating mechanism that regulates the boundaries of drug capitalism, balancing its economic imperatives with the need for social recognition and cohesion. In this sense, the addiction regime plays a crucial role in the (re)production of symbols, structures of meaning, values, and forms of socialization that politically and socioculturally optimize accumulation processes within both legal and illegal drug economies, legitimizing their regulatory frameworks and enforcement.

Analyzing the capitalist drug economy through this lens underscores the role of culture in shaping a symbolic order that defines shared meanings around drug consumption, individual responsibility, and the state’s role in managing the crises of violence produced by the drug trade. Through a specific case study, this article seeks to explore the addiction regime as a mediating mechanism within the global drug economy under contemporary capitalism.

While numerous anthropological studies examine the cultural aspects of addiction and related issues (Bourgois, 2003; Bourgois & Jeffrey, 2009; Epele, 2010; Medrano Villalobos, 2013; Soto, 2013; Morín, 2015; Zavala, 2018), few analyze the current opioid epidemic from a symbolic perspective, particularly in the Mexican context (París Pombo & Pérez Floriano, 2015).

Existing research on fentanyl in Mexico primarily focuses on legal frameworks, public health and human rights concerns, international relations, and the reconfiguration of the drug economy, including shifting cartel dynamics (Bergman, 2016; Díaz Cuervo, 2016; Le Cour Grandmaison et al., 2019; Fleiz et al., 2020; Friedman et al., 2022, 2023; Magis Rodríguez et al., 2022; Soto Rodríguez, 2022; Pérez Ricart & Ibarrola García, 2023). As of 2024, no published studies have been identified that explore the cultural dimensions of addiction, particularly in relation to fentanyl in Mexico.

This article explores the role of symbols and socially shared meanings surrounding drugs within the context of the so-called opioid epidemic, particularly in the era of fentanyl (Schwarz, 2016; Westhoff, 2019; Fernández Menéndez, 2020; Macy, 2022). Through a review of bibliographic and journalistic sources, an analysis of institutional videos aimed at addiction prevention, and interviews with drug users in the border city of Tijuana, Baja California, this study examines key aspects of the addiction regime in Mexico. The focus is on the cultural dimensions that sustain and legitimize the state’s actions and stance on substance use.

The following sections provide a brief overview of the history of drug trafficking in Mexico and the emergence of the fentanyl crisis in the United States, as well as the growing production, distribution, and consumption of this substance in Mexico. Next, the article addresses substance use in Tijuana, drawing on both statistical data and lived experiences, with a particular focus on the role of hopelessness in the potential rise of opioid and other substance use along the northern border. The article also examines a series of addiction prevention videos produced by the federal government, emphasizing certain symbolic aspects of what is referred to here as the addiction regime.

FENTANYL: THE ORIGIN OF AN EPIDEMIC

The emergence of fentanyl in Mexico represents the latest chapter in the country’s long history of drug trafficking. This story has been recounted from multiple perspectives, each highlighting different aspects of the issue. Traditionally, the political history of drugs has taken center stage, emphasizing the role of institutional actors—mayors, governors, military officials, and presidents— in shaping the structures of drug trafficking. This approach often portrays a narrative of infamy, corruption, and impunity within the Mexican political class, illustrating its involvement in the evolution of drug trafficking networks from their inception to the present (Hernández, 2010; Astorga, 2015, 2016; Valdés Castellanos, 2015; Smith, 2021).

Other approaches focus on analyzing the legal framework and state structures that have facilitated, and even strengthened, the power of criminal organizations, taking into account the role of globalization and international exchanges in the formation of global criminal networks (Bergman, 2016; Díaz Cuervo, 2016). As evident, Mexico’s institutional history of drugs offers resources for study; however, as Luis Astorga (2016) notes:

In Mexico, the history of the uses, perceptions, and social actors related to the currently most concerning prohibited substances (such as marijuana, opioids, and cocaine) has not yet garnered the attention of academia. (p. 18)

It is important to highlight that significant studies exist on the cultural history of drugs in Mexico—and Latin America—though much remains to be explored (Pérez Montfort, 1999, 2016; Campos, 2012, 2022).

In this brief historical overview, it is important to remember that the concept of drugs itself implies a socio-institutional framework that defines their legality or illegality, as well as the socially accepted contexts, myths, and meanings surrounding their consumption and users. Imposing contemporary interpretations on ancient practices may be anachronistic, even if they bear some resemblance to current times. The history of drugs is inherently tied to their prohibition and regulation. The concept of drugs—regardless of whether the term is used—does not exist without a political-institutional will and order that sanctions their use through practices, meanings, and symbols. In essence, the history of drugs is the history of the addiction regimes established over time.

In Pre-Columbian Mexico, the use of stimulants such as tobacco, alcohol, and hallucinogenic plants (entheogens) was already subject to strict class-based restrictions, creating distinctions in how these substances were consumed. Their regulation led to significant tensions between Indigenous peoples and Spaniards, between political and ecclesiastical authorities, and played a key role in the sociocultural reconfiguration of the colonial era (Campos, 2022). According to Campos (2022, p. 360), during the colonial period and into the early 20th century:

As in much of the Western world, the most widely used and lamented drug in Mexico was undoubtedly alcohol, especially when consumed by “the people.” Here, old prejudices and tropes from the colonial era, particularly the concern over the consumption of indigenous pulque (a fermented milky drink made from the maguey cactus) by the lower classes, merged with the increasingly widespread transnational abstinence discourses.

During the Porfiriato, the consumption of opium was both legal and legitimate, with quantities ranging from 800 kilograms to 12 tons imported between 1888 and 1911 (Astorga, 2016). The use of laudanum and other opioids as remedies for pain, antidiarrheals, and various ailments continued into the early 20th century, widely advertised to the public. It is important to note that morphine use was typically associated with the upper classes. It was only with its association with Chinese immigrants that the stigmatization of this drug began (Astorga, 2016; Pérez Montfort, 2016). On the other hand, until just a few years ago, the use of marijuana was linked to the lower classes, particularly peasants, soldiers, and prison populations, associated with a degenerationist view of the Mexican race, which aligned with the dominant eugenics discourses of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was said that:

All marijuana users are degenerative rogues, they enjoy the company of criminal people or belong to such groups, they have no regard for life, they become insensitive to external excitants, they are apathetic, amoral, and emotionally detached; therefore, it is a herculean task to try to cure them. (Astorga, 2016, p. 44)

Similarly, Pérez Montfort (2016, p. 72) observes that during the first four decades of the 20th century, “criminality and marijuana, along with their association with the humble and proletarian classes, became a commonplace connection.”

By the 1940s, the Mexican state of Sinaloa and its surrounding regions had already become major producers of opium gum and heroin. Although domestic consumption of these substances remained minimal—particularly after the violent repression and expulsion of Chinese immigrants—this era set the foundation for Mexico’s role as a key supplier of narcotics, primarily to the U.S. market during World War II and beyond (Astorga, 2015, 2016; Smith, 2021). Valdés Castellanos (2015) describes the period between 1940 and 1980 as the peak of Mexican organized drug trafficking, marked by monopolistic consolidation. However, heroin use within Mexico itself remained nearly nonexistent (Smith, 2021).

Until the 1970s, cocaine consumption in Mexico was virtually nonexistent. However, during the 1980s and 1990s, the drug became central to the country’s drug economy. As Smith (2021) notes, shifts in dominant substances are tied to global drug flow reconfigurations, which correspond to geopolitical conflicts and institutional responses to the social problems associated with drug use. In other words, changes in the “drug of choice” reflect shifts in addiction regimes. It was during this period that the term cartel began to be used to describe criminal organizations involved in drug trafficking, following the precedent set by Colombian groups. These organizations later gained international notoriety through TV series like Narcos and similar media portrayals.

Since the late 1990s, a new market has emerged around so-called designer drugs, including benzodiazepines, stimulants (such as amphetamines and methamphetamines), MDMA (ecstasy), opioids, and synthetic cannabinoids. The recent history of synthetic narcotics in Mexico remains to be fully written, but their origins can be traced. Like many other similar substances, these drugs initially had medical origins, stemming from the search for new treatments for various ailments, particularly mental or psychiatric conditions, as well as analgesics, antitussives, and antidiarrheals. Often, the discovery of a new medication occurs by chance, leading to the development of derivative formulas whose utility, more than medical, aligns with legal and commercial strategies centered on acquiring patents and generating profits.

Behind the contemporary addiction to synthetic drugs, two converging forces are at play: on one hand, the growth of a pharmaceutical complex that has turned health into an inexhaustible source of private wealth; and on the other, the increasing medicalization of modern life’s challenges, which has promoted drug consumption among progressively younger populations, based on alleged behavioral disorders3 (Davies, 2014; Schwarz, 2016). The case of methamphetamine is older, with its emergence in the early 20th century and its role during World War II well documented. Its use in Mexico appears to have been primarily medical and marginal until just a few decades ago (Pérez Montfort, 2016; Ohler, 2017; Hager, 2021). Today, however, methamphetamine—or “ice”—represents the greatest public health risk, being the most consumed drug among Mexican youth after tobacco, marijuana, and alcohol (Observatorio Mexicano de Salud Mental y Consumo de Drogas, 2022).

In this context, the appearance of fentanyl has marked a significant turning point in the evolution of contemporary addiction regimes. Synthesized by Paul Janssen in 1959 and approved for medical use in the United States in 1968, fentanyl was initially used as an analgesic during surgeries and to alleviate pain in cancer patients and those in terminal states. However, today its medical use has been largely overshadowed by its recreational consumption, particularly as a substitute for other legally sold synthetic opioids, following the restrictions on its availability due to the overdose crisis that has affected the United States since the late 1990s (McGreal, 2018).

The restrictions on legal access to medications such as OxyContin, Percocet, Vicodin, and other similar drugs—resulting from a prolonged legal battle against major pharmaceutical companies over their role in the opioid epidemic (Higham & Horwitz, 2022)—led Mexican traffickers to fill the void with heroin from Sinaloa and Nayarit (Quinones, 2016).

However, by the second decade of the 21st century, Mexican traffickers began mixing—and in some cases, simply replacing—natural heroin with fentanyl. The reasons are clear: on one hand, fentanyl’s production and distribution are cheaper, as it is a synthetic substance that is easy to transport and doesn’t require extensive labor, land, or cultivation for production (Pergolizzi et al., 2021). Moreover, the profits per kilogram of fentanyl far exceed those of natural heroin. According to Fernández Menéndez (2020), “Making a fentanyl pill takes at most two hours, and each kilogram of this substance produces 20 kilograms of pills. The profit is between $1 280 000 and $1 920 000 for each kilogram of pills” (p. 32), far surpassing the $80 000 profit generated by converting 15 kilograms of opium gum into one kilogram of pure heroin. It is no surprise, then, that Mexican criminal organizations such as the Sinaloa cartel and the Jalisco New Generation cartel have shifted focus to producing this substance. On the street, fentanyl is known by various names: Apache, China Girl, Dance Fever, China Town, Goodfellas, Friend, Great Bear, Jackpot, He-Man, King Ivory, Murder 8, Poison, and Tango & Cash; in Latin American countries, it is also referred to as White or Synthetic Heroin, N-30, Fenta, Tango, or China White.

Due to its potency—50 times greater than heroin and 100 times more than morphine— determining the exact dosage of fentanyl is challenging. Combined with the precarious conditions of its clandestine production, fentanyl becomes a highly lethal drug. Just two or three milligrams of fentanyl can be fatal for a new user, and five milligrams can be deadly for a regular user (Grisel, 2019). The situation is further complicated by the fact that in recent years, fentanyl has been mixed into other drugs, such as crystal meth, cocaine, pills, heroin, and even marijuana. As a result, users often unknowingly consume fentanyl, sometimes with fatal consequences (Westhoff, 2019; Quinones, 2021; Macy, 2022).

This situation led to a dramatic increase in overdose deaths in the United States, with approximately 350 000 fatalities between 1999 and 2016, resulting in social and economic costs estimated at $3 billion (McGreal, 2018). According to Macy (2022), by the end of 2021, opioid addiction—especially synthetic opioids like fentanyl—had become the leading destroyer of family structures in the United States. In 2022, the number of overdose deaths in the country due to synthetic opioids, primarily fentanyl, reached 73 838 (Center for Disease Control, 2024). Until 2016, there was limited information on the trafficking and consumption of fentanyl in Mexico; however, by 2018, the United States reported the seizure of approximately 150 kilograms of fentanyl (Dudley, 2019). By 2023, the Mexican government reported confiscating 1 848 kilograms of fentanyl within its borders (Comisión Nacional de Salud Mental y Adicciones [CONASAMA], 2024).

The history and data presented above highlight the threat fentanyl poses in Mexico, both due to its role in the drug trafficking economy and the health risks associated with its consumption. The following section offers an analysis of the changing perception and presence of fentanyl in Tijuana, located on the northwestern border of Mexico. In addition, some ethnographic observations and visual material analyses are provided, suggesting that while opioid consumption does not yet constitute a public health crisis, the future risk of a synthetic opioid epidemic in the country may stem from the growing prevalence of conditions that Case and Deaton (2020) refer to as a social structure of despair, or what is preferred to be called here, hopelessness.

Hopelessness and Drug Addiction on the Northern Border of Mexico

The trafficking and consumption of fentanyl is a significant international public health issue. It not only affects consumers directly but also creates a complex web of negative relationships that impact various aspects of daily life. In particular, these practices play a key role in shaping perceptions of security, as if the drug itself is an entity that increasingly affects even those who do not consume it. Based on a review of journalistic articles published in national newspapers (El Universal [2016- 2023], Excelsior [2020-2024], and El País [2023]) and local newspapers (El Sol de Tijuana [2017- 2023], El Imparcial [2023], and Semanario Zeta [2023]), this section presents some of the narratives constructed around the issue, covering the emergence of this drug in the local public discourse.

At the national level, the first references to fentanyl were largely informational, warning the public about this emerging threat. The new alarm focused on the opioid crisis in the United States, which placed responsibility on Mexico for the transit of this substance across the northern border. The informational content regarding fentanyl’s uses, high addictiveness, and profitability was supplemented with reports on clandestine laboratories where the drug was being produced (De Mauleón, 2016). Within months, the threat of fentanyl began to take on a more menacing character, described allegorically as a demon—trendy, but a problem for the United States, not Mexico. By mid-2016, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) was reporting a lack of data on the trafficking of this drug within Mexican territory (Redacción El Universal, 2016).

Journalistic coverage increasingly prioritized fentanyl over heroin, emphasizing its heightened potency and reinforcing its status as the deadliest drug in the United States. By 2017, the narrative had shifted to highlight connections between Mexican drug traffickers and Chinese producers, symbolically recasting fentanyl as an illicit Asian immigrant passing through Mexico on its way to devastate the United States—akin to a terrorist threat to national security. The term opioid epidemic became the dominant discourse (Sancho, 2017). In 2018, Mexico’s National Security Commissioner, Renato Sales Heredia, reframed the issue, stating that rising violence in Mexico was a direct consequence of U.S. demand for heroin and fentanyl—shifting the perceived threat from an external crisis to a domestic concern (García, 2018). By 2019, some reports suggested that Mexico still had time to prevent widespread fentanyl consumption (Redacción El Universal, 2019). However, as the year progressed, the narrative evolved into one of impending crisis, warning of a potential wave of fentanyl-related deaths, with Tijuana identified as the primary trafficking hub along the northern border (Toribio, 2020).

Paradoxically, while some sources suggested that fentanyl threatened the profitability of Mexican cartels by replacing other substances in the market, the Sinaloa and Jalisco Nueva Generación cartels were simultaneously being identified as the primary exporters of the drug to the United States (Espino, 2019; Reyes & Ramírez, 2020). Between 2019 and 2023, fentanyl seizures, the dismantling of clandestine laboratories, and violent confrontations between organized crime and the Secretaría de la Defensa Nacional (SEDENA)4 became routine occurrences, all linked to fentanyl trafficking (Redacción El Universal, 2020). By 2024, fentanyl seizures were concentrated in the border states of Baja California, Chihuahua, and Sonora (Flores Martínez, 2024). Throughout this period, authorities repeatedly emphasized that fentanyl consumption in Mexico remained minimal, though concerns persisted about its potential to escalate into a widespread crisis. In response, Mexico, China, and the United States sought joint strategies to curb the growing threat (Camhaji, 2023).

Locally, newspapers such as El Sol de Tijuana, El Imparcial, and Semanario Zeta have extensively covered the fentanyl crisis and its impact on the Tijuana-San Diego region, highlighting the drug’s transborder nature and its widespread effects. Early local reports described fentanyl as a “highly addictive” controlled substance, posing a significant risk to youth (Pérez, 2022). In early 2017, the first fentanyl seizures in the city were reported—both in kilogram and pill form—prompting various regional prevention and security organizations to take action. By 2023, fentanyl seizures had escalated to hundreds of thousands of pills (Hernández, 2018; Saucedo, 2018). By 2020, local newspapers began documenting the first fentanyl overdoses in Tijuana, drawing attention to the government’s failure to contain the growing threat. Reports also noted a shift in drug consumption patterns—from uninformed to informed use. Initially, users were unaware they were ingesting fentanyl-laced substances, but over time, some began actively seeking the drug for its rapid and intense effects. While most fentanyl trafficked through the region remains destined for the U.S. market, a small but notable portion is now being consumed in Tijuana itself (Dayebi, 2023).

The initial social perception of fentanyl, largely shaped by media coverage, appears to be materializing. By 2020, there were 1,568 recorded treatment requests for heroin use and 18 related to synthetic drugs. Between 2014 and 2022, 28 opioid-related deaths were officially reported (CONASAMA, 2024). However, much of the heroin consumed may have been contaminated with fentanyl—an issue difficult to assess due to the lack of studies analyzing drug impurities and their prevalence. Moreover, the reported death toll presents significant discrepancies. In 2022, toxicology studies conducted by the Tijuana Forensic Medical Service detected fentanyl in 691 fatalities, a stark contrast to previous official statistics, suggesting a far more complex reality (CONASAMA, 2024). This discrepancy indicates that fentanyl may be implicated in deaths beyond overdoses, including violent incidents and accidents.

Currently, neither Tijuana nor the rest of Mexico has an institutional program or adequate resources to systematically track fentanyl’s presence and its role in overdose-related, violent, or accidental deaths. Over time, fentanyl has evolved from being seen as a foreign, malevolent substance—often associated with migration and carrying racist connotations due to its Asian origin—to being recognized as a legitimate public health and security issue. Once regarded merely as a substance in transit to the United States, it is now perceived as a local threat, particularly in northern Mexico. At this point, it became a state priority to establish both legal and discursive frameworks to define institutional responses to fentanyl and other substances. This included shaping public perceptions of users and potential victims, as well as determining how the government would address this emerging crisis.

In response to the media-driven perception of fentanyl as a risk and amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, on March 17, 2020, the federal government launched a campaign for addiction prevention. In his report that day, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador stated:

This will be the most direct campaign to raise awareness about the harm caused by drugs, because we are going to expand it and make it intensive. Drug consumption causes many misfortunes, much pain, much sadness, especially among young people and their families, and we must counteract all the promotion that is made, projecting an image that this world of drugs and crime is a happy world—a world of, as we’ve said, luxury, mansions, branded clothes, jewelry, a pleasurable life—when in reality it’s hell. Even the most famous criminals have to live on the run; they have no peace. That is not life. And the worst thing is that there are drugs that destroy lives in months, completely harmful drugs that ruin young people’s lives. (López Obrador, 2020, 07:45)

The slogan “En el mundo de las drogas no hay final feliz” (In the world of drugs, there is no happy ending) framed Mexico’s new addiction prevention strategy. Spokesperson Jesús Ramírez Cuevas explained that the campaign aimed to: “not stigmatize consumers, but to speak the truth about the reality of what it means for a person, especially for a teenager or a young person, to consume substances” (Ramírez Cuevas, 2020, 43:38). As reflected in the president’s statement, and seen in several of the produced videos,5 the audiovisual message seeks to contrast the allure of drug consumption and trafficking with the devastating personal and family consequences both activities bring. Additionally, other videos highlight the risks of consuming specific substances, such as cigarettes, alcohol, methamphetamines, cocaine, heroin, crack, and fentanyl, generally illustrating a supposed progressive line of drug consumption—from less harmful substances like tobacco to more destructive ones like crack or meth.

However, there is a contradiction between the campaign’s objective and the audiovisual product it produced. On one hand, the alarming narrative is undermined by the visual aesthetic of the spots. The videos mimic the sensationalist style of television series and hip-hop music videos, where the use of narcotics and the criminal lifestyle associated with them are exalted and celebrated. In one of the videos, a hip-hop song states: “The monkey, the fentanyl, destroys your senses, if you smoke or inhale it, you’re dying alive [...] Listen to what I’m telling you, because it’s true, the drug business is something that ends badly” (Gobierno de México, 2022, 01:17). By borrowing the aesthetic of media that glorify drug use and narco culture, the intended message is ultimately diluted. In this case, the spot closely mirrors the videos of hip-hop artist Dharius, whose portrayal of drugs, sex, and violence as symbols of social triumph reinforces these ideals (Dharius Oficial, 2016).

The success of series like Narcos: Mexico, El Señor de los Cielos, El Chapo, and others illustrates that the perception, especially among youth, of the rationality behind choosing a criminal life is far more complex than a simple calculation of potential physical and social consequences (Morín, 2015; Valenzuela Arce, 2024). However, there is a deeper issue with this strategy.

In this campaign, both media narco-culture and the government share the same aesthetic, one that associates drug addiction, violence, and crime. As a result, the campaign fails in its goal of not stigmatizing the user. It resorts to what can be called “addiction porn,” depicting individuals injecting drugs, staggering like zombies, passed out on the streets, or overdosing in abandoned lots. This approach makes it difficult to shift the public’s response to the issue (Gobierno de México, 2022; Secretaría de Educación Pública, 2023; Secretaría de Gobernación, 2023). On the contrary, Marsh (cited in Macy, 2022) argues: “Very often, people think that no one recovers from this disease [addiction], so if we don’t highlight recovery stories, the perception is that the only end to this is prison or death, and that’s simply not true” (p. 19).

Unfortunately, the federal government’s campaign “En el mundo de las drogas no hay final feliz” (In the world of drugs, there is no happy ending) perpetuates the stigma and criminalization of addiction. It relies on an appealing, media-popular aesthetic without fully understanding—or perhaps overlooking—the complexity of how these messages are received by young people, as well as the underlying reasons for drug use and trafficking.

Almost the entire prevention strategy targets the young population, assuming a rational cost- benefit analysis regarding the decision to use drugs. However, the reality is that most opioid users on the border, particularly in Tijuana, are individuals living on the streets, many of whom have experienced traumatic deportation processes (París Pombo & Pérez Floriano, 2015). Given the brief airtime of the spots on public television and their limited exposure in schools, it is clear that these messages rarely reach those most at risk. It is as if the dominant discourse surrounding fentanyl prevention is focused solely on saving lives that would be mourned, while those already trapped in the cycle of addiction are viewed as expendable, “bare life” (Butler, 2010). The Si te drogas, te dañas (If you do drugs, you harm yourself) series targets middle-class youth, for whom the risk of fentanyl and other substances lies in misinformation or deliberate deception (Secretaría de Educación Pública, 2023).

On the other hand, the Testimonios series uses “addiction porn” to depict ruined individuals whose lives are nearly destroyed. In one testimony, Yair states, “I am already a rotten person, don’t do anything to fix me” (Sistema de Educación Media Superior de la Universidad de Guadalajara, 2020, 00:21). In the era of fentanyl, the addiction regime perpetuates discourses around consumption, addiction, and its treatment in a way that creates contentious language (Roseberry, 2002), which regulates the social meaning of drugs while legitimizing the state’s differentiated approach to managing populations involved in various forms of the trafficking economy. As such, this campaign functions as a cultural mediation mechanism of the addiction regime, contributing to the management and indirect exploitation of precarious populations, effectively extracting value through drug consumption and reinforcing certain social values in the media representations of users (Fuentes Díaz, 2020).

It is not surprising that one of the spots from the Si te drogas, te dañas series compares methamphetamine addiction to its use in warfare during World War II:

The Nazis created methamphetamines to turn their soldiers into tireless and dehumanized beings. Under its effect, the Nazi army started the worst war in history and created extermination camps. Today, crystal meth is used to control the minds of young people seeking pleasure, as well as day laborers and maquiladora workers who need energy to work day and night. (Gobierno de México, 2021, 00:01)

The military analogy legitimizes a dual strategy: on one hand, prevention aimed at the lives of young people who are seen as valuable; on the other, a repressive approach toward those already addicted, as well as dealers and traffickers, whose only fate is death or self-destruction.

On the border, the lives that often go unnoticed received the campaign too late, and their fate seems to be tied to what could be called “addiction porn”—a path of ruin with no way out. Yuri, a 25-year-old woman living in the Zona Norte of Tijuana, a region notorious for its high levels of prostitution, drug sales, and related violence, began using crystal meth at 16. For the past three years, she has exclusively smoked fentanyl, known on the street as China White. When asked about the risks of overdose, she responded:

Well, I only smoke China now, look [shows a small pink bar of content]. I’ve never really gotten messed up, it all depends on how you use it, some people put a ton and yeah, they fade out […] and you gotta slap them or splash some water on them [laughs]. I only once felt like I was going out, but a friend slapped me and I woke up like, “What the hell?”, but that’s it. I only smoke China now, ‘cause the effect is faster and stronger. Before I only used crystal, but not anymore, now it’s all China […] the problem is it wears off fast, and you gotta buy more […] it lasts about four hours for me, so yeah, I gotta save up some cash […] it costs 50 pesos for the little bag. (Yuri, personal communication, February 20, 2023)

Yuri says she lives with her family and meets with friends to use drugs in shared rooms, hotels, or specific spots in the alleys of Zona Norte. Her conversation is erratic and at times delirious, claiming to own several hotels in Tijuana and to be a business partner of Carlos Slim. Whenever we spoke with her, she mentioned that she was waiting for some earnings that her sister insists on not giving her. On one occasion, she even invited us to vacation in the coastal town of San Felipe to stay in an apartment that, she says, “my friend Ernesto lets me use, do you know him? […] Peña Nieto.” (Yuri, personal communication, February 10, 2023). It was impossible to determine whether Yuri’s mental deterioration is solely due to her fentanyl addiction or if it stems from an underlying condition; it is likely that both factors have mutually reinforced each other. To support her addiction, Yuri prostitutes herself on the streets of Zona Norte. She even mentions that sometimes young people in luxury cars take her to orgies in various hotels in Tijuana, events she doesn’t remember much about, since she always consumes fentanyl. Yuri is unconcerned about the risk of overdose and consumes China, fully aware of what it contains. While one might assume that knowledge of fentanyl’s risks would deter its use, some studies show the opposite (Bailey et al., 2022).

One might think that overdose deaths would deter customers from dealers whose clients die, but anecdotal evidence suggests the opposite. Opioid addicts are so desperate to feel numb that they see death as a sign that the supply source is desirable, the “real thing.” (Case & Deaton, 2020, p. 120)

Addiction has its own rationality, one that is not reflected in the spots created by the Ministry of Health. The last time we spoke with Yuri was in May 2024, and she was pregnant. She said she had gotten pregnant out of love and assured us: “I know whose it is, I know it’s that guy’s” (Yuri, personal communication, May 9, 2024), referring to a man without a name, the father of a baby who will most likely be born with fentanyl withdrawal syndrome (Grisel, 2019).

Alongside the conscious use of fentanyl, there are users of non-opioid substances who unknowingly consume drugs contaminated with or substituted by fentanyl. Violeta is a 35-year- old woman from a working-class neighborhood in Monterrey, Nuevo León. Due to family issues and what seems to be her use of methamphetamine, she left her three teenage children with her mother and moved to Tijuana. She claims to have incomplete studies in administration and has worked in various companies and maquiladoras in both Monterrey and Tijuana. For the past two years, she has been living in a hotel in the Zona Norte, and at night she walks the streets looking for clients, prostituting herself to pay for her room, drugs, and a meal each day. Violeta has been sexually abused on several occasions, two of which occurred when she worked in bars in the Zona Norte. To cope with the painful memories of family abandonment, poor jobs, and the sexual abuse she has endured, Violeta has been smoking meth for several years, and fentanyl has never caught her interest:

I was never really into that Chiva they call [heroin], I just smoke crystal, and honestly, it’s way more chill. Back in La Campanera [a popular neighborhood in Monterrey], I remember it was all wild with the homies, I even smoked with Babo, the singer from Cartel de Santa [hip-hop group], and with the fat guy, the one they call Millonario, that fucking pig [laughs]. I know them, I even got pics with them and all that […] but since I got to Tijuana, I just smoke to chill, that stuff relaxes me real good, I forget about everything […] all that bullshit that happened to me […] now crystal just relaxes me, it doesn’t get me crazy […] in general, with the people I smoke with, it’s all chill guys, that shit just relaxes all of us. (Violeta, personal communication, April 15, 2024)

However, methamphetamine is a stimulant drug, not a relaxant (Grisel, 2019). It is highly likely that what Violeta and her friends are smoking is methamphetamine contaminated with fentanyl or, possibly, small doses of the opioid. Given the lack of institutional harm reduction strategies in Tijuana, such as substance testing, users often have no idea what they are actually consuming— something that has been well-documented (Fleiz et al., 2020; Bailey et al., 2022; Friedman et al., 2022, 2023; Magis Rodríguez et al., 2022). The trauma she has experienced, her precarious situation as a sex worker, and her addiction have made it even harder for her to secure formal employment, despite her repeated attempts at various maquiladoras in Tijuana. Violeta buys at least two packets of meth a day, each costing 50 pesos, offering an immediate, inexpensive, and potentially fatal escape from the overwhelming hopelessness that defines her life.

Although there is no scientific consensus on the causes of addiction, it is widely accepted that the convergence of genetic, psychological, and environmental factors increases the risk of substance dependence, though not everyone becomes addicted (Grisel, 2019). Various studies indicate that the loss of meaning in life, particularly in the context of relative precariousness, plays a significant role in the rise of drug addiction. Jennifer Silva (2019) found that the denial of dignity and social recognition has been a powerful catalyst for the opioid crisis in former coal mining communities in the eastern United States, now deindustrialized. This has contributed to a crisis of meaning among their residents, who endure precarious jobs that offer little respect.

It is no coincidence that the rise in fentanyl and other substance use is primarily observed among individuals who have fallen into states of despair or, more accurately, hopelessness. Floating populations, migrants in transit, deportees, maquiladora workers displaced from their origins who are unable to establish a sense of labor dignity or social recognition in the city, and others are part of this reality. This is further exacerbated by the constant harassment and violence from law enforcement structures targeting some of these populations (Morales et al., 2020; Villafuerte Guillén & Pacheco Gómez, 2022).

All these conditions are concentrated and intensified at the northern border of Mexico, as several studies have documented (Solís, 2009; Acosta et al., 2012; Medrano Villalobos, 2013; Soto, 2013; Contreras Velasco, 2016; Velasco & Albicker, 2016; Del Monte Madrigal, 2021; Hernández-Hernández, 2021). Opioid overdose deaths (due to heroin and/or fentanyl), as well as the rise in consumption of other substances like crystal meth, are expressions of a growing sense of despair and hopelessness among very specific populations. However, the economic conditions of the country (Orraca Romano & Iriarte Rivas, 2019), combined with the highly addictive nature of substances like fentanyl, especially now that it is mixed into other drugs, make these addictions a risk that must be urgently addressed.

This issue is not about uninformed or misled individuals taking a wrong path, nor is it merely a media spectacle focused on the “pornography of addiction” that perpetuates sensationalist imagery surrounding drug trafficking, its victims, and perpetrators. On the contrary, our study shows that the growing presence of fentanyl in border cities like Tijuana is a symptom of worsening structural conditions of despair and hopelessness, along with the fatalities they cause. While, at the very least, the consumption of fentanyl and other substances on the northern border of the country should serve as a warning, it is not simply a crisis stemming from poor decisions made by uninformed youth. Instead, it acts as a stark reminder of the rising structural conditions of hopelessness in Mexico, particularly among vulnerable populations in the border region and other parts of the country.

The experiences of Yuri and Violeta illustrate how addiction is intensified in situations of hopelessness, particularly when gender-based conditions are involved. Neither of them was aware of the government campaign, and contrary to its claims, fentanyl consumption does not symbolize any risk for them. Instead, their conscious use of China White and crystal meth represents a specific kind of freedom—a brief respite from the oppressive and violent conditions they face daily. According to their accounts, this is something they share with others they meet to use drugs. Unlike the grim portrayal of addiction in government ads, they view their consumption as a temporary escape from their harsh realities, a momentary reprieve from despair and hopelessness.

Due to space limitations, it is not possible to delve deeper into the interviews. However, we propose the following hypothesis: In contexts of extreme precarity and violence, such as the border areas of Zona Norte in Tijuana, the contradictions between institutional and hegemonic representations of addiction and its actors, on one hand, and the concrete conditions, practices, and meanings of drug consumption, on the other, reveal the functioning of mediation mechanisms within a specific sector (partial regime) of the capitalist economy.

These contradictions highlight what has been referred to here as the “addiction regime,“ specifically addressing the cultural mediation mechanisms through which actors, actions, and substances in the global drug economy are symbolically and discursively (re)produced. However, the functioning and perpetuation of this addiction regime in the era of fentanyl is closely tied to the reproduction of conditions of despair and hopelessness that make addiction, at least momentarily, a source of freedom or escape for users. Without these structural conditions, it is likely that the addiction regime would take on different characteristics, as seen with substances like tobacco, alcohol, and, more recently, marijuana.

CONCLUSIONS

Contrary to the claims made in the Secretaría de Salud6 addiction prevention campaign, people do not choose a path of self-destruction and death simply due to a lack of information or poor decision- making. As Case and Deaton (2020, p. 94) state, “People kill themselves when it no longer seems worth living, when dying seems better than continuing to live.” Precarious jobs that offer neither dignity nor a sense of purpose, the absence of social recognition in cities lacking mechanisms for social integration, limited access to quality higher education, inadequate or nonexistent public healthcare systems, and crises in foundational structures of belonging (such as families) have all been identified as key contributors to the rise in deaths of despair (McGreal, 2018; Case & Deaton, 2020).

The issue is not that “In the world of drugs, there is no happy ending”, as research shows the contrary (Grisel, 2019; Quinones, 2021; Szalavitz, 2021; Macy, 2022). The problem is that in Tijuana, as in the rest of Mexico, there is no institutional harm reduction policy related to drug use, and the state’s capacity to address addiction remains limited. Some organizations, like Prevencasa, promote harm reduction strategies in Zona Norte—such as needle exchange, substance testing, safe consumption spaces, and outpatient medical care—which focus on reducing the negative externalities of substance use (disease transmission, injuries, overdoses, police harassment) rather than relying on criminalization or abstinence-focused therapeutic approaches, often with religious undertones (Odgers Ortiz, 2022). It’s not that a happy ending is impossible; the problem is that the government’s approach prioritizes a sensationalist view of addiction and violence, contributing to the racialization of despair, which is ultimately a consequence of the destruction of the living conditions of a dignified working class (Case & Deaton, 2020; Hansen et al., 2023).

This article offers a first approach to the concept of the addiction regime in contexts of despair/hopelessness, supporting the proposed framework. Campaigns like “In the world of drugs, there is no happy ending” are part of the cultural apparatus that sustains the addiction regime in Mexico, establishing symbolic and discursive frameworks that shape how addiction, its actors, characteristics, and consequences are understood. The pornographic gaze in many of these ads dehumanizes the addict, aiming to protect an imagined middle-class youth while racializing the drug-dependent individual as someone whose existence and death are presumed beyond the reach of state action. This process transforms the addict into disposable life, serving the spectacle of addiction and the political-economic mechanisms of drug trafficking in the era of fentanyl.

REFERENCES

Acosta, F., Solís, M. y Alonso, G. (2012). Grado de apropiación de la ciudad y percepciones sobre la calidad de vida en ciudades de la frontera norte de México. Cofactor, 3(6), 9-42. https://biblat.unam.mx/es/revista/cofactor/articulo/grado-de-apropiacion-de-la-ciudad-y-percepciones-sobre-la-calidad-de-vida-en-ciudades-de-la-frontera-norte-de-mexico [ Links ]

Aglietta, M. (2001). El capitalismo en el cambio de siglo: la teoría de la regulación y el desafío del cambio social. New Left Review, 7, 16-70. [ Links ]

Astorga, L. (2015). Drogas sin fronteras. Debolsillo. [ Links ]

Astorga, L. (2016). El siglo de las drogas. Debolsillo. [ Links ]

Bailey, K, Abramovitz, D., Patterson, T. L., Harvey-Vera, A. Y., Vera, C. F., Rangel, M. G., Friedman, J., Davidson, P., Bourgois, P. y Strathdee, S. A. (2022). Correlates of recent overdose among people who inject drugs in the San Diego/Tijuana border region. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 240(109644), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.109644 [ Links ]

Bergman, M. (2016). Drogas, narcotráfico y poder en América Latina. Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Bourgois, P. (2003). In search of respect. Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Bourgois, P. y Jeffrey S. (2009). Righteous dopefiend. University of California Press. [ Links ]

Boyer, F. (1990). The regulation school: A critical introduction. Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Butler, J. (2010). Marcos de guerra. Paidós. [ Links ]

Camhaji, E. (2023, 31 de mayo). López Obrador plantea a EE UU y China “una tregua” en la crisis del fentanilo. El País.https://elpais.com/mexico/2023-05-31/lopez-obrador-plantea-a-ee-uu-y-china-una-tregua-en-la-crisis-del-fentanilo.html [ Links ]

Campos, I. (2012). Home grown: Marijuana and the origins of Mexico’s war on drugs. University of North Carolina Press. [ Links ]

Campos, I. (2022). The making of pariah drugs in Latin America. En P. Gootenberg (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of global drug history (pp. 358-371). Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Case, A. y Deaton A. (2020). Deaths of despair and the future of capitalism. Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Center for Disease Control. (2024). Drug overdose deaths: Facts and figures. https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates#Fig [ Links ]

Comisión Nacional de Salud Mental y Adicciones (Conasama). (2024). Informe de la demanda y oferta de fentanilo en México: generalidades y situación actual. Secretaría de Salud. https://www.gob.mx/salud/conadic/documentos/informe-de-la-demanda-y-oferta-de-fentanilo-en-mexico-generalidades-y-situacion-actual [ Links ]

Contreras Velasco, O. (2016). Vivir en los márgenes del Estado: un estudio en la frontera México-Estados Unidos. Región y Sociedad, 28(65), 235-262. https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1870-39252016000100235 [ Links ]

Davies, J. (2014). Cracked: Why psychiatry is doing more harm than good. Icon. [ Links ]

Dayebi, A. (2023, 10 de septiembre). Consumo de fentanilo se está haciendo de manera consciente: Secretaría de Salud. El Sol de Tijuana. https://www.elsoldetijuana.com.mx/local/consumo-de-fentanilo-se-esta-haciendo-de-manera-consciente-secretaria-de-salud-10674154.html [ Links ]

De Mauleón, H. (2016, 1 de agosto). La DEA tiene un nuevo demonio. El Universal. https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/entrada-de-opinion/columna/hector-de-mauleon/nacion/2016/08/1/la-dea-tiene-un-nuevo-demonio/ [ Links ]

Del Monte Madrigal, J. A. (2021). Vidas rompibles en el vórtice de precarización: políticas de expulsión, procesos de exclusión y vida callejera en la ciudad fronteriza de Tijuana, México. Norteamérica, 16(2), 183-207. https://doi.org/10.22201/cisan.24487228e.2021.2.433 [ Links ]

Dharius Oficial. (2016, 1 de septiembre). La Durango [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yyknJd3EeIo [ Links ]

Díaz Cuervo, J. C. (2016). Drogas. Caminos hacia la legalización. Booklet. [ Links ]

Dudley, S. (2019, 19 de febrero). El fentanilo en México explicado en 8 gráficos. InSight Crime. https://insightcrime.org/es/investigaciones/el-fentanilo-en-mexico-explicado-en-8-graficos/ [ Links ]

Epele, M. (2010). Sujetar por la herida. Una etnografía sobre drogas, pobreza y salud. Paidós. [ Links ]

Espino, M. (2019, 30 de octubre). Sedena ve a Ovidio Guzmán como el principal traficante de fentanilo a EU. El Universal. https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/nacion/sedena-ve-ovidio-guzman-como-el-principal-traficante-de-fentanilo-eu/ [ Links ]

Fernández Menéndez, J. (2020). La nueva guerra: del Chapo al fentanilo. Grijalbo. [ Links ]

Fleiz, C., Arredondo, J., Chavez, A., Pacheco, L., Segovia, L. A., Villatoro, J. A., Cruz, S. L., Medina-Mora, M. E. y De la Fuente, J. R. (2020). Fentanyl is used in Mexico’s northern border: Current challenges for drug health policies. Addiction, 115(4), 778-781. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14934 [ Links ]

Flores Martínez, R. (2024, 4 de enero). FGR destruye más de 5 millones de pastillas de fentanilo y 82 kilos de opioides. Excelsior. https://www.excelsior.com.mx/nacional/fgr-destruye-cinco-millones-pastillas-fentanilo-y-opioides/1628408 [ Links ]

Forsyth, M. (2019). Una breve historia de la borrachera. Ariel. [ Links ]

Friedman J., Bourgois, P., Godvin, M., Chavez, A., Pacheco, L., Segovia, L. A. Beletsky, L. y Arredondo, J. (2022). The introduction of fentanyl on the US-Mexico border: An ethnographic account triangulated with drug checking data from Tijuana. International Journal of Drug Policy, 104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2022.103678 [ Links ]

Friedman J., Godvin, M., Molina, C., Romero, R., Borquez, A., Avra, T., Goodman-Meza, D., Strathdee, S., Bourgois, P. y Shover, C. L. (2023). Fentanyl, heroin, and methamphetamine-based counterfeit pills sold at tourist-oriented pharmacies in Mexico: An ethnographic and drug checking study. Drug Alcohol Depend, 249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2023.110819 [ Links ]

Fuentes Díaz, A. (2020). Violencia y extracción. Hacia una necropolítica de la acumulación. En A. Fuentes Díaz y F. J. Cortázar Rodríguez (Coords.), Vidas en vilo. Marcos necropolíticos para pensar las violencias actuales (pp. 21-42). Universidad de Guadalajara. [ Links ]

García, D. A. (2018, 5 de febrero). Sales liga violencia en México a alta demanda de heroína y fentanilo en EU. El Universal.https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/nacion/sociedad/sales-liga-violencia-en-mexico-alta-demanda-de-heroina-y-fentanilo-en-eu/ [ Links ]

Gobierno de México. (2021, 23 de octubre). ENPA,Si te drogas, te dañas. Metanfetaminas [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j56Uar4wtPM [ Links ]

Gobierno de México. (2022, 18 de enero). Estrategia Nacional para la Prevención de Adicciones [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jaFovAuAb6E&list=PLp9_0Iw1G1brltwCAOLmmoUV5-74e1NUF&index=8 [ Links ]

Gootenberg, P. (Ed.). (2022). The Oxford handbook of global drug history. Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Grisel, J. E. (2019). Never enough: The neuroscience and experience of addiction. Doubleday. [ Links ]

Hager, T. (2021). Diez drogas. Sustancias que cambiaron nuestras vidas. Crítica. [ Links ]

Halpern, J. y Blistein, D. (2019). Opium. How an ancient flower shaped and poisoned our world. Hachette Books. [ Links ]

Hansen, H., Netherland, J. y Herzberg, D. (2023). Whiteout: How racial capitalism changed the color of opioids in America. University of California Press. [ Links ]

Hernández, A. (2010). Los señores del narco. Grijalbo. [ Links ]

Hernández, J. M. (2018, 23 de junio). Amenaza fentanilo con llegar a Tijuana. El Sol de Tijuana.https://www.elsoldetijuana.com.mx/local/amenaza-fentanilo-con-llegar-a-tijuana-1787221.html [ Links ]

Hernández-Hernández, A. (2021). Una frágil frontera entre la delincuencia y las drogas: la Zona Norte de Tijuana. Cultura y Droga, 26(32), 153-185. https://doi.org/10.17151/culdr.2021.26.32.8 [ Links ]

Higham, S. y Horwitz, S. (2022). American cartel. Inside the battle to bring down the opioid industry. Twelve. Le Cour Grandmaison, R., Morris, N. y Smith, B. T. (2019). [ Links ]

Le Cour Grandmaison, R., Morris, N. y Smith, B. T. (2019). El boom del fentanilo en Estados Unidos y la crisis del opio en México: ¿Oportunidades en medio de la violencia? Wilson Center-Mexico Institute. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/el-boom-del-fentanilo-en-estados-unidos-y-la-crisis-del-opio-en-mexico-oportunidades-en [ Links ]

López Obrador, A. M. (2020, 17 de marzo). Versión estenográfica de la conferencia de prensa matutina del presidente Andrés Manuel López Obrador. Presidencia de México. https://amlo.presidente.gob.mx/17-03-20-version-estenografica-de-la-conferencia-de-prensa-matutina-del-presidente-andres-manuel-lopez-obrador/ [ Links ]

Macy, B. (2022). Raising Lazarus. Hope, justice, and the future of America’s overdose crisis. Little, Brown and Company. [ Links ]

Magis Rodríguez, C. L., Villafuerte García, A., Angulo Corral, M. de L., Pacheco Bufanda, L. I., Salazar-Arriola, S. A., Ramos Rodríguez, M. E., Villanueva Lechuga, D., Meza Hernández, J. A., Cruz Rico, C. L. y Rico Cervantes, B. R. (2022). Sobredosis fatales y no fatales por consumo de opioides en el contexto de la pandemia por COVID-19 en el norte de México. Salud Pública y Epidemiología, 3(28), 7-13. https://dsp.facmed.unam.mx/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/COVID-19-No.28-04-Sobredosis-fatales-y-no-fatales-por-consumo-de-opioides-1.pdf [ Links ]

McGreal, C. (2018). American overdose. The opioid tragedy in three acts. Public Affairs. [ Links ]

Medrano Villalobos, G. (2013). El consumo de heroína en Tijuana, una subcultura de la resistencia. En M. D. París Pombo y Pérez Floriano, L. R. (Coords.), La marca de las drogas. Violencias y prácticas de consumo (pp. 161-196). El Colegio de la Frontera Norte; Juan Pablos Editor. [ Links ]

Morales, M., Rafful, C., Baker, P., Arredondo, J., Kang, S., Mittal, M. L., Rocha-Jiménez, T., Strathdee, S. A. y Beletsky, L. (2020). “Pick up anything that moves”: A qualitative analysis of a police crackdown against people who use drugs in Tijuana, Mexico. Health and Justice, 8(9), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40352-020-00111-9 [ Links ]

Morín, E. (2015). La maña. Un recorrido antropológico por la cultura de las drogas. Debate. [ Links ]

Observatorio Mexicano de Salud Mental y Consumo de Drogas. (2022). Demanda de tratamiento por consumo de sustancias psicoactivas en 2021. Secretaría de Salud; Comisión Nacional contra las Adicciones; Secretariado Técnico del Consejo Nacional de Salud Mental; Servicios de Atención Psiquiátrica. https://www.gob.mx/salud/conadic/documentos/observatorio-mexicano-de-salud-mental-y-consumo-drogas?state=published [ Links ]

Odgers Ortiz, O. (2022). Religión, violencia y drogas en la frontera norte de México: la resemantización del mal en los centros de rehabilitación evangélicos de Tijuana, Baja California. Frontera Norte, 34, 1-27. https://doi.org/10.33679/rfn.v1i1.2208 [ Links ]

Ohler, N. (2017). High Hitler: las drogas en el III Reich. Crítica. [ Links ]

Orraca Romano, P. P. e Iriarte Rivas, C. G. (2019). Los salarios de los trabajadores mexicanos en México y Estados Unidos durante el periodo del TLCAN, 1994-2017. En C. Calderón Villarreal y S. Rivas Aceves (Coords.), El TLCAN a 24 años de su existencia: retos y perspectivas (pp. 117-146). El Colegio de la Frontera Norte; Universidad Panamericana; Ediciones Eón. [ Links ]

París Pombo, M. D. y Pérez Floriano, L. R. (Coords.). (2015). La marca de las drogas. Violencias y prácticas de consumo. El Colegio de la Frontera Norte; Juan Pablos Editor. [ Links ]

Pérez Montfort, R. (1999). Yerba, goma y polvo: drogas, ambientes y policías en México, 1900- 1940. Era. [ Links ]

Pérez Montfort, R. (2016). Tolerancia y prohibición. Aproximaciones a la historia social y cultural de las drogas en México 1840-1940. Debate. [ Links ]

Pérez Ricart, C. A. e Ibarrola García, A. (2023). La transición hacia el fentanilo. Cambios y continuidades del mercado de drogas en México (2015-2022). Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 36(53), 15-36. https://doi.org/10.26489/rvs.v36i53.1 [ Links ]

Pérez, C. (2022, 19 de octubre). ¿Qué es el fentanilo arcoíris? Los riesgos de la droga que está encendiendo alertas. El Sol de Tijuana. https://www.elsoldetijuana.com.mx/doble- via/salud/que-es-el-fentanilo-arcoiris-los-riesgos-de-la-droga-que-esta-encendiendo-alertas-9060254.html [ Links ]

Pergolizzi, J., Magnusson, P., LeQuang, J. A. K. y Breve, F. (2021). Illicitly manufactured fentanyl entering the United States. Cureus, 13(8). https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.17496 [ Links ]

Quinones, S. (2016). Dreamland. The true tale of America’s opiate epidemic. Bloomsbury. [ Links ]

Quinones, S. (2021). The least of us: True tales of American and hope in the time of fentanyl and meth. Bloomsbury. [ Links ]

Ramírez Cuevas, J. (2020, 17 de marzo). Versión estenográfica de la conferencia de prensa matutina del presidente Andrés Manuel López Obrador. Presidencia de México. https://amlo.presidente.gob.mx/17-03-20-version-estenografica-de-la-conferencia-de-prensa-matutina-del-presidente-andres-manuel-lopez-obrador/ [ Links ]

Redacción El Universal. (2016, 9 de junio). Fentanilo enriquece a los cárteles mexicanos: NYT. El Universal.https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/articulo/mundo/2016/06/9/fentanilo-enriquece-los-carteles-mexicanos-nyt/ [ Links ]

Redacción El Universal. (2019, 12 de febrero). México está a tiempo de evitar consumo masivo de fentanilo. El Universal.https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/nacion/mexico-esta-tiempo-de-evitar-consumo-masivo-de-fentanilo/ [ Links ]

Redacción El Universal. (2020, 18 de diciembre). Aumenta decomiso de fentanilo y metanfetaminas en el país: Sedena. El Universal.https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/nacion/sedena-aumenta-decomiso-de-fentanilo-y-metanfetaminas-en-el-pais/ [ Links ]

Reyes, G. y Ramírez, P. (2020, 23 de febrero). Fentanilo, la droga que enriquece a mexicanos y mata a miles en EU. El Universal.https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/nacion/fentanilo-la-droga-que-enriquece-mexicanos-y-mata-miles-en-eu/ [ Links ]

Roseberry, W. (2002). Hegemonía y lenguaje contencioso. En G. M. Joseph y D. Nugent (Comps.), Aspectos cotidianos de la formación del Estado. La revolución y la negociación del mando en el México moderno (pp. 213-226). Ediciones Era. [ Links ]

Sancho, V. (2017, 6 de junio). Narcos mexicanos y chinos ingresan fentanilo al país: EU. El Universal.https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/articulo/mundo/2017/06/6/narcos-mexicanos-y-chinos-ingresan-fentanilo-al-pais-eu/ [ Links ]

Saucedo, U. (2018, 10 de julio). Aumenta decomiso de fentanilo en BC. El Sol de Tijuana. https://www.pressreader.com/mexico/el-sol-de-tijuana/20180710/281530816785426?srsltid=AfmBOopSPKEPs9oggRyhPE16hDzjQKq2EFnrY3ikdsLCa6GQ3ASC52dx [ Links ]

Schwarz, A. (2016). ADHD nation. Children, doctors, big pharma, and the making of an American epidemic. Scribner. [ Links ]

Secretaría de Educación Pública. (2023, 17 de abril). El fentanilo te mata.Promo 2. Estrategia en el aula: prevención de adicciones [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c3GVDktyHPQ&list=PLp9_0Iw1G1brltwCAOLmmoUV5-74e1NUF&index=2 [ Links ]

Secretaría de Gobernación. (2023, 1 de enero). [TV] Spot SEGOB (PDCDDQ1 Fentanilo) (veda en 12 estados) [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JbaLdb5PE-M [ Links ]

Silva, J. M. (2019). We’re still here. Pain and politics in the heart of America. Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Sistema de Educación Media Superior de la Universidad de Guadalajara. (2020, 14 de agosto). Testimonio Yair, Estrategia Nacional para la Prevención de las Adicciones [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CxWffU4fNjg&list=PLp9_0Iw1G1brltwCAOLmmoUV5-74e1NUF&index=74 [ Links ]

Smith, B. (2021). The dope. The real history of the Mexican drug trade. Norton. [ Links ]

Solís, M. (2009). Trabajar y vivir en la frontera.Identidades laborales en las maquiladoras de Tijuana. Miguel Ángel Porrúa; El Colegio de la Frontera Norte. [ Links ]

Soto Rodríguez, M. (2022). Fentanilo, el gran negocio del crimen organizado: implicaciones en el combate a las drogas. Revista de Relaciones Internacionales de la UNAM, (140), 89-116. https://revistas.unam.mx/index.php/rri/article/view/83040 [ Links ]

Soto, E. (2013). El consumo de drogas y sus efectos en la construcción identitaria de los sujetos. En M. D. París Pombo y L. R. Pérez Floriano (Coords.), La marca de las drogas. Violencias y prácticas de consumo (pp. 197-220). El Colegio de la Frontera Norte. [ Links ]

Szalavitz, M. (2021). Undoing drugs: How harm reduction is changing the future of drugs and addiction. Balance. [ Links ]

Toribio, L. (2020, 5 de marzo). Traficaron fentanilo y morfina desde el INER; análisis de la Cuenta Pública 2018. Excelsior.https://www.excelsior.com.mx/nacional/traficaron-fentanilo-y-morfina-desde-el-iner-analisis-de-la-cuenta-publica-2018/1368001 [ Links ]

Valdés Castellanos, G. (2015). Historia del narcotráfico en México. Apuntes para entender el crimen organizado y la violencia. Aguilar. [ Links ]

Valenzuela Arce, J. M. (2024). Corridos tumbados. Bélicos ya somos, bélicos morimos. Ned Ediciones. [ Links ]

Velasco, L. y Albicker S. L. (2016). Deportación y estigma en la frontera México-Estados Unidos: atrapados en Tijuana. Norteamérica, 11(1), 99-129. https://doi.org/10.20999/nam.2016.a004 [ Links ]

Villafuerte Guillén, U. y Pacheco Gómez, C. (2022). Integral state on the northern border of Mexico: Administration and surveillance of subaltern groups in Tijuana, Baja California. Dialectical Anthropology, 46, 142-162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10624-022-09652-x [ Links ]

Westhoff, B. (2019). Fentanyl, Inc.How rogue chemists are creating the deadliest wave of the opioid epidemic. Atlantic Monthly Press. [ Links ]

Zavala, O. (2018). Los cárteles no existen. Narcotráfico y cultura en México. Malpaso Ediciones. [ Links ]

Received: September 17, 2024; Accepted: October 31, 2024

texto en

texto en