Introduction

Pleurotus (Fr.) P. Kumm. (Agaricales, Pleurotaceae) is a genus of saprophytic fungi of great importance since most of its species are edible, and some are considered medicinal (Lin et al., 2022). Several species can be cultured on diverse agricultural and industrial waste materials, which has led to the cultivation of several species of Pleurotus representing a viable source of income through the production of low-cost food with high quality (Gregory et al., 2007; Raman et al., 2021). Species in this genus are characterized by the flabelliform to dimidiate pileus, attached to the substrate by a short, lateral, sometimes eccentric stipe, which occasionally is absent; gills are decurrent, tight or widely separated, with margin smooth to crenate and involute; hyphal system can be monomitic or dimitic and the spore print is whitish, cream color, or lilac (Flecha Rivas et al., 2014).

Pleurotus species could be confused with other genera such as Hohenbuehelia S. Schulz., which has rubbery and flexible fruiting bodies and thick-walled sterile cells on the gills; Panus Fr. and Panellus P. Karst. characterized by their solid fruiting bodies with a hairy cap surface, and amyloid spores; and Phyllotopsis E.-J. Gilbert & Donk ex Singer, which has pinkish allantoid spores (Arora, 1986). Furthermore, Lentinus Fr. can also be confused with some of the previous genera; nevertheless, it differs due to its elastic fruiting bodies when young, becoming leathery at maturity, and gills typically with serrated edges (Moreno, 1975).

Due to these problems with the determination of the species and the taxonomic relationships with similar genera, until the year 2000, 23 species and varieties of Pleurotus were reported in Mexico. The taxonomic revision of Guzmán (2000) reduced from the 23 species to only seven. From those, two are now accepted as Lentinus species (Index Fungorum, 2023): L. scleropus (Pers.) Fr. (= P. hirtus Guzmán) and L. levis (Berk. & M.A. Curtis) Murrill (= P. levis (Berk. & M.A. Curtis) Singer). Then, the five known Pleurotous species in Mexico, recognized by Guzmán (2000) are P. bajacalifornicus Esteve-Rav., G. Moreno & N. Ayala (Moreno et al., 1993); P. djamor var. djamor (Rumph. ex Fr.) Boedijn (Guzmán et al., 1993); P. opuntiae (Durieu & Lév.) Sacc. (Estrada-Torres and Aroche, 1987); P. ostreatus (Jacq.) P. Kumm. (Guzmán, 1977) and P. smithii Guzmán (Guzmán, 1975). In addition, P. dryinus (Pers.: Fr.) Kumm. was reported by Guzmán (1975) and Valenzuela et al. (1981), but Guzmán (2000) considered it as a non-recognized species in “a complex species in Mexico”. Moreno-Fuentes et al. (1994) also reported P. dryinus from Chihuahua, the same state where later Moreno-Fuentes et al. (2004) recorded P. floridanus Singer, thus resulting in a total of seven species of Pleurotus in Mexico.

Some species of Pleurotus are known to produce anamorphs with arthrospores on coremia (=synnemata) (Hilber, 1982). Such anamorphs were previously placed within the genus Antromycopsis Pat. & Trab. and they were classified as Hyphomycetes (Deuteromycotina) (Stalpers et al., 1991). However, Camino-Vilaró and Mena-Portales (2019) proposed to conserve the species under the name Pleurotus cystidiosus O.K. Mill. Hilber (1982) grouped species of Pleurotus with coremia formation under the subgenus Coremiopleurotus Hilber (Capelari and Fungaro, 2003) and assigned P. cystidiosus (1969) as its type species. Other species with coremia formation are P. abalonus Y.H. Han, K.M. Chen & S. Cheng; P. australis Cooke & Massee; P. fuscosquamulosus Reid & Eicker; P. purpureo-olivaceus Segedin, P.K. Buchanan & J.P. Wilkie; and P. smithii (Guzmán et al., 1980; Capelari and Fungaro, 2003; Lin et al., 2022). This latter, described from Mexico City, is the only member of Coremiopleurotus known from Mexico. In recent sampling carried out by the authors of the present work, some Pleurotus specimens with the formation of coremia were observed and collected in Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, Mexico, whose morphological and molecular characterization led them to report them as P. cystidiosus as a new record for Mexico. Hence, the objective of this work is to document the presence of P. cystidiosus in Mexico and provide a detailed description of the specimens found in the country.

Materials and Methods

Fungal material, isolation, and morphological characterization

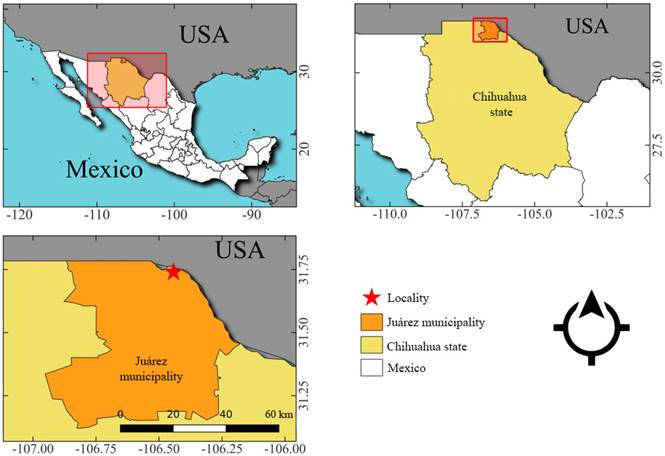

Basidiomata were observed on an Ulmus sp. tree in the urban zone of Ciudad Juárez, in Chihuahua State, Mexico (31°44'22.6"N; 106°26'33.3"W) (Fig. 1) and collected in September 2021 and August 2022. To isolate a strain, portions of context from the fruiting bodies were inoculated in Petri dishes with potato dextrose agar (PDA) in aseptic conditions and maintained in the dark at 25±1 °C until full colonization. The shape, color, and size of basidiomata were recorded in fresh specimens. Microscopical analyses were carried out by manual cuts of different parts of the basidiomata and coremia, mounted in 5% KOH and observed with a Nikon C-DS stereo microscope (Tokyo, Japan) and a Nikon Eclipse E200 microscope (Tokyo, Japan), equipped with a Nikon CoolPix 4500 camera (Tokyo, Japan). The coremia grown in Petri dishes were photographed using a polyfocal microscope Leica Z16 APO A (Wetzlar, Germany) and processed in the Leica Application Suite v. 4.3 software (Wetzlar, Germany).

The specimens studied are deposited in the herbarium MEXU (Thiers, 2024), with duplicates in the UACJ herbarium of the Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez, Mexico.

DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and sequencing

Genomic DNA was isolated from a small sample of mycelium that was cultivated on a PDA medium following a CTAB 3% extraction protocol (Doyle and Doyle, 1987). The mycelium was placed in a 2 ml tube with a Sterilized tungsten Sphere, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and ground with a QIAGEN TissueLyser LT (Hilden, Germany). After adding 500 μl of CTAB and 2 μl of β-mercaptoethanol per sample, the tubes were incubated at 45 °C for 30 minutes at 300 rpm in an Eppendorf Thermomixer C (Hamburg, Germany). Next, 500 μl of SEVAG (chloroform: isoamyl alcohol; 24:1) was added and stirred for 30 minutes at 85 rpm in a Fisher Clinical Rotator (Hampton, USA). The mixture was centrifuged at 13000 × g for 10 minutes in an Eppendorf centrifuge 5424R (Hamburg, Germany). The supernatant was transferred to a 1.5 ml tube, and 500 μl of isopropanol was added, gently mixed, and stored at -20 °C for one hour. Subsequently, the mixture was centrifuged for 10 minutes at 12000 × g, in a Eppendorf centrifuge 5424R (Hamburg, Germany) and the supernatant was discarded. The pellet was washed with 70% EtOH at -20 °C, vacuum-dried for 5 minutes, and suspended in 50 μl of ultrapure water. The sample was quantified using a NanoDrop 2000 instrument (Waltham, USA), and its integrity was visually verified on a 1% agarose gel stained with RedGel™ using an Analytik Jena UVP transilluminator (Jena, Germany).

The ITS5 (5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′) and ITS4 (5′-GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG-3′) were used to amplify the complete ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 region (Schoch et al., 2012) using the PCR Mix (5’BIO, Mexico) and a Thermofisher Scientific Veriti Thermocycler (Waltham, USA). The PCR amplicons were visualized on a 1% agarose gel stained with RedGel™ and the successful amplicons underwent treatment with ExoSAP-IT™ according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer. Clean PCR reactions were sequenced at both ends in the Laboratorio de Secuenciación Genómica de la Biodiversidad of the Laboratorio Nacional de Biodiversidad (LANABIO) of the Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Phylogenetic analyses

The obtained sequence was assembled and curated by inspecting their chromatograms in Sequencher software v. 5.2.3 (Ann Arbor, USA). Reference sequences from specialized literature (Zervakis et al., 2004; 2019; Yang et al., 2007; Horisawa et al., 2013; Liu et al, 2015; Shnyreva and Shnyreva, 2015; Barh et al., 2019; Lin et al., 2022) were downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (GenBank, 2024) (Table 1), and aligned using the online version of MAFFT v. 7 (Katoh et al., 2002, 2017; Katoh and Standley, 2013).

Table 1: Species, vouchers, localities, and GenBank (2024) accessions of the Pleurotus (Fr.) P. Kumm. specimens for the phylogenetic analysis. The Agaricus and Psathyrella accessions were used as outgroups. The sequence obtained in this study is marked in bold.

| Taxon | Voucher/Strain | Locality | ITS Accession Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agaricus bisporus (J.E. Lange) Imbach | CBS 11668 | USA | MH859080 |

| Pleurotus abalonus Y.H. Han, K.M. Chen & S. Cheng | A1 | China | JN671965 |

| Pleurotus abalonus Y.H. Han, K.M. Chen & S. Cheng | 149 | China | KX688474 |

| Pleurotus abalonus Y.H. Han, K.M. Chen & S. Cheng | ATCC 28787 | Taiwan | AY315798 |

| Pleurotus abalonus Y.H. Han, K.M. Chen & S. Cheng | CBS 100129 | China | NR103594 |

| Pleurotus abalonus Y.H. Han, K.M. Chen & S. Cheng | CGMCC 37470 | China | KX787086 |

| Pleurotus abieticola R.H. Petersen & K.W. Hughes | 3509 | China | MK209085 |

| Pleurotus abieticola R.H. Petersen & K.W. Hughes | HMJAU56580 | China | MT163335 |

| Pleurotus abieticola R.H. Petersen & K.W. Hughes | HKAS45570 | China | KP771697 |

| Pleurotus abieticola R.H. Petersen & K.W. Hughes | HKAS45720 | China | KP771696 |

| Pleurotus abieticola R.H. Petersen & K.W. Hughes | HKAS46100 | China | KP771695 |

| Pleurotus australis Sacc. | CBS 100127 | China | EU424276 |

| Pleurotus cystidiosus O.K. Mill. | CBS 29735 | USA | AY315766 |

| Pleurotus cystidiosus O.K. Mill. | FP1683 | USA | AY315776 |

| Pleurotus cystidiosus O.K. Mill. | D412, D413, D417, D419, D420 | USA | AY315774, AY315770, AY315773, AY315771, AY315767 |

| Pleurotus cystidiosus O.K. Mill. | VT1780 | USA | AY315769 |

| Pleurotus cystidiosus O.K. Mill. | CCBAS 466 | USA | FJ608592 |

| Pleurotus cystidiosus O.K. Mill. | AG 55/466 CCBAS | Russia | FJ608592 |

| Pleurotus cystidiosus O.K. Mill. | P19, P25 | China | EF437221 KY962441 |

| Pleurotus cystidiosus O.K. Mill. | ATCC28597 | China | EF514244 |

| Pleurotus cystidiosus O.K. Mill. | MEXU 30551 | Mexico | OR532762 |

| Pleurotus cystidiosus O.K. Mill. | IFO30784 | Korea | AY265818 |

| Pleurotus cystidiosus O.K. Mill. | NBRC 30607 | Japan | AB733141 |

| Pleurotus cystidiosus O.K. Mill. | ATCC 28598 | South Africa | AY315777 |

| Pleurotus dryinus (Pers.) P. Kumm. | AG I/467, AG II/468, AG III/470 | Russia | KF932722, KF932723, KF932724 |

| Pleurotus dryinus (Pers.) P. Kumm. | TENN 7947 | Denmark | AY450343 |

| Pleurotus dryinus (Pers.) P. Kumm. | P45, P99 | China | KY962461, MG282439 |

| Pleurotus fuscosquamulosus D.A. Reid & Eicker | EGDA Pl23 | Egypt | MW915606 |

| Pleurotus fuscosquamulosus D.A. Reid & Eicker | LGAM P50 | Grece | KF280330 |

| Pleurotus salmoneostramineus Lj.N. Vassiljeva | P36 | China | KY962452 |

| Pleurotus salmoneostramineus Lj.N. Vassiljeva | YL1 | China | AY728273 |

| Pleurotus smithii Guzmán | CCRC 36229, CBS 68982 | Mexico | AY265851 |

| Pleurotus smithii Guzmán | CBS 68082 | Mexico | EU424317 |

| Pleurotus smithii Guzmán | ATCC 46391 | Mexico | AY315784 |

| Pleurotus tuber-regium (Fr.) Singer | MCCT P7 | India | OQ916341 |

| Pleurotus tuber-regium (Fr.) Singer | PYKM100 | India | OQ891321 |

| Pleurotus tuber-regium (Fr.) Singer | MCCT AP2 | India | OQ920982 |

| Psathyrella secotioides G. Moreno, Heykoop, Esqueda & Olariaga | AH31746 | Mexico | KR003281 |

The alignments were reviewed in Mesquite v. 3.81 (Maddison and Maddison, 2023), followed by minor manual adjustments to ensure character homology among the taxa. The matrices consisted of 51 sequences of ITS and included 712 positions. Phylogenetic inferences were estimated using the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method in RAxML v. 8.2.10 (Stamatakis, 2014) with a GTR+G nucleotide substitution model with 1000 bootstrap resampling replicates performed with the GTR+G model.

Bayesian analysis was conducted using Mr Bayes v. 3.2.6 × 64 (Huelsenbeck and Ronquist, 2001). The information block for the matrix included two simultaneous runs, four Monte Carlo chains, a temperature set at 0.2, and a sampling of 10 million generations (standard deviation ≤0.1) with trees sampled every 1000 generations. The two simultaneous Bayesian runs continued until convergence parameters were met, and the standard deviation fell below 0.0001 after 10 million generations. The final tree was edited using FigTree v. 1.4.4 (Rambaut, 2018).

Results

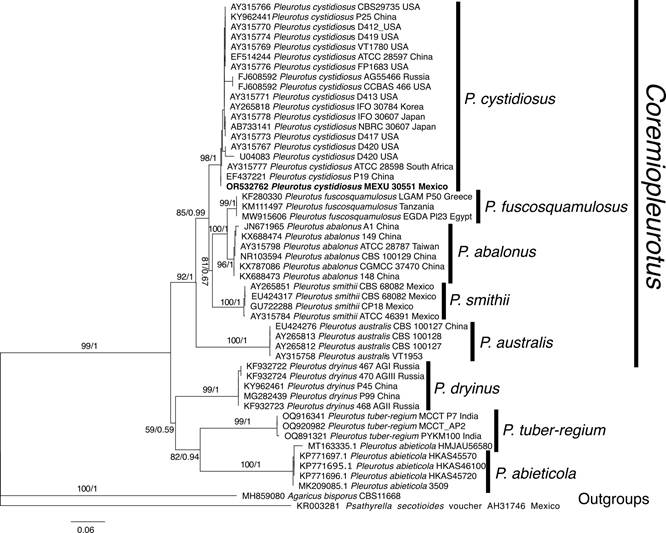

We successfully amplified and sequenced the ITS region of the Pleurotus collection from Chihuahua (GenBank accession of the ITS sequence: OR532762). The initial BLAST yielded similarity (>99%) with P. cystidiosus from voucher specimens and isolate strains. Both Bayesian and Maximum Likelihood analyses (Fig. 2) grouped our sequence as P. cystidiosus, supporting the existence of this distinctive taxon in the north of our country (1 Bayesian posterior probability (PP) and 98% bootstrap resampling values for ML).

Figure 2: Phylogram of Bayesian inference (BI) tree from the ITS sequence data of 50 specimens. The numbers above branches represent Bootstrap Values (BS) for Maximum Likelihood and Bayesian Posterior Probabilities (PP), respectively. The scale bar represents the expected number of nucleotide substitutions per site. The sequence obtained in this study is in bold. Accession numbers of GenBank (2024) are indicated in each sequence.

Taxonomy

Basidiomycota

Agaricomycetes

Agaricales

Pleurotaceae

Pleurotus cystidiosus O.K. Mill. Mycologia 61: 889, 1969. Figs. 3, 4.

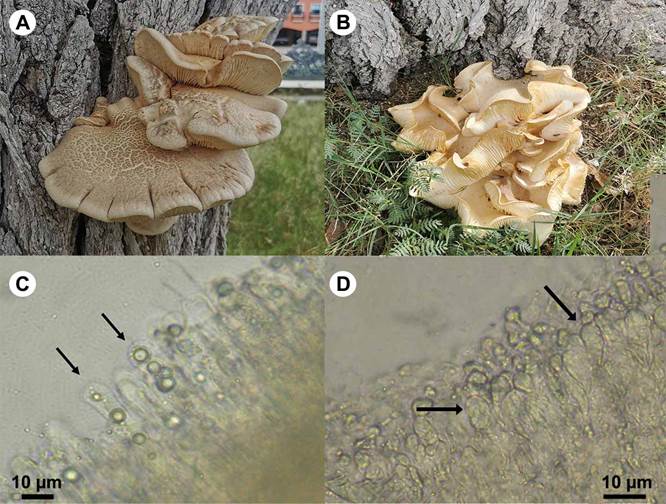

Figure 3: Pleurotus cystidiosus O.K. Miller, teleomorph. A. basidiome on an Ulmus sp. trunk; B. basidiome on the base of an Ulmus L. tree; C. pleurocystidia; D. cheilocystida.

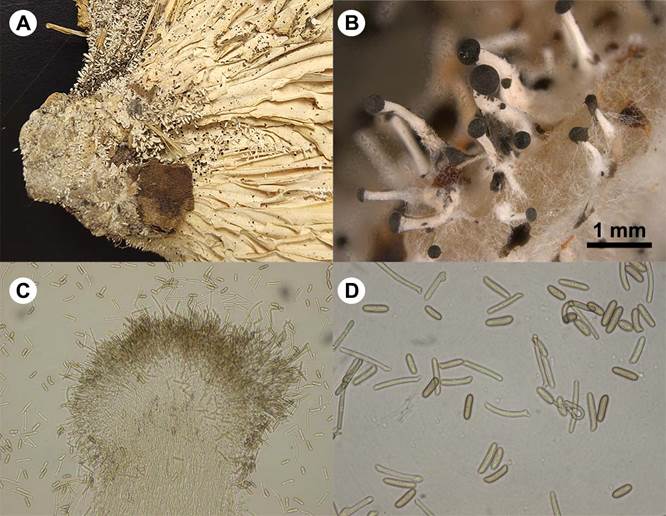

Figure 4: Pleurotus cystidiosus O.K. Miller, anamorph. A. coremia on basidiome; B. polyphocal microscopy of coremia on PDA; C. coremia in light microscopy; D. artrospores in light microscopy.

= Stilbum macrocarpum Ellis & Everh., J. Mycol. 2(9): 103. 1886. (Ellis & Everh.) Stalpers, Seifert & Samson, Can. J. Bot. 69(1): 7. 1991.

= Antromycopsis broussonetiae Pat. & Trab., Bull. Soc. Mycol. Fr. 13: 215. 1897.

HOLOTYPE: USA. Indiana, Brown County, Hoosier National Forest, F.H. Berry CS-66-083-2-A (BFDL).

Teleomorph

Basidiomata pileate, substipitate to sessile, growing in overlapping groups of up to 15 individuals; pileus plane-convex, flabelliform, 60-130 mm in diameter, surface smooth to wrinkled, whitish when young, turning yellowish-cream to buff color when mature; lamellae decurrent, tight, white when young, turning yellowish-cream when mature; pseudostipe lateral, 5-10 mm long, eccentric; basidiospores 14-17.5 × 4-5 µm, cylindric, hyaline, inamyloid, thin-walled; basidia 40-65 × 7-10 µm, clavate; pleurocystidia 40-50 × 7-8 µm, cylindric, hyaline to light brown, with abundant granular content; cheilocystidia 20-28 × 8-10 µm, subglobose to pyriform, thin-walled, hyaline to ochraceous; hyphal system monomitic; pileus trama formed by generative, thin-walled, clamped hyphae 5-12 µm wide, slightly branched hyphae, occasionally with widened endings; cuticle of the pileus with abundant pileocystidia 28-40 × 8-10 µm, clavate to cylindrical, with a rounded apex, lamellae trama with clamped, hyaline hyphae 55-18 µm wide, mixed with amorphous, ochraceous elements.

Anamorph

Coremia developed abundantly on the surface of culture medium (PDA), gregarious, or occasionally in groups attached by the base, 0.8-2.5 mm in height, with a white stipe and apex with a droplet of dark liquid; stipe formed by hyaline hyphae, septate and clamped, which fragment forming cylindric arthrospores, brown or sometimes hyaline, 17-25 × 5-7.5 µm.

Habit: lignicolous, growing on an Ulmus sp. tree.

Distribution: Algeria (Stalpers et al., 1991), Argentina (Lechner et al., 2004), Brazil (Capelari, 1999), China (Zervakis et al., 2004), Cuba (Camino-Vilaró et al., 2018), Greece (Zervakis et al., 1992), India (Zervakis et al., 2004), Indonesia (Stalpers et al., 1991), Israel (Stajić et al., 2003), Japan (Zervakis et al., 2004), Pakistan (Hussain et al., 2015), Philippines, South Africa (Zervakis et al., 2004), Russia (Shnyreva and Shnyreva, 2015), Taiwan (Jong and Peng, 1975), Thailand (Zervakis et al., 2004), and United States of America (Miller, 1969).

Specimens examined: MEXICO. Chihuahua, municipality Ciudad Juárez, growing at the base of an Ulmus sp. tree, 6.IX.2021, M. Lizárraga s.n. (UACJ 3396), loc. cit., 25.VIII.2022, M. Lizárraga s.n. (UACJ 3397); loc. cit., M. Lizárraga s.n. (MEXU 30551). GenBank accession of the ITS sequence: OR532762.

Notes: Pleurotus cystidiosus can be easily confused with P. smithii, which also forms coremia. These two species can be differentiated by the presence of abundant pleurocystidia in P. cystidiosus, rarely only in the young stages of P. smithii, subglobose cheilocystidia in the teleomorph of P. cystidiosus, absent in P. smithii; as well as by the shorter segments 5-11(-15) × 3.2-5(-6) µm of conidiophore elements in the anamorph of P. smithii (Guzmán et al., 1991). Other very similar species that also form coremia are P. abalonus which differs by its smaller basidiospores (10.5-13.5 × 3.8-5 µm) and slender cheilocystidia (7-8.5 µm, diam.) (Guzmán, 2000). Pleurotus purpureo-olivaceus presents spherical and sessile conidiomata and is restricted to Australia and New Zealand, as is P. australis, which is distinguished macroscopically by its dark reddish-brown pileus and microscopically by its smaller basidiospores (10.5-14 × 4-6 µm), pleurocystidia, and cheilocystidia (16-25 × 5 µm) (Segedin et al., 1995). Pleurotus fuscosquamulosus presents cylindrical to clavate cheilocystidia bearing an apical sterigma-like structure with an apical small capitulum (Torta et al., 2019), absent in our collections of P. cystidiosus.

Discussion

The species of Pleurotus included in the subgenus Coremiopleurotus are very similar and, therefore, difficult to distinguish using only morphological features. Accordingly, it is necessary to complement taxonomic studies with ITS sequences to delimit these species correctly. The close relationship between P. cystidiosus and P. smithii has been discussed from morphological and molecular perspectives. Capelari and Fungaro (2003) considered them synonyms based on Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA (RAPD). Zervakis et al. (2004) later established taxonomic independence using ITS sequences. Currently, the rDNA ITS region is considered the universal barcode for fungal species recognition (Schoch et al., 2012), and recent phylogenetic studies on the genus Pleurotus have shown the independence of both species and the close relationships within the subgenus, nowadays considered within clade one by Lin et al. (2022).

It is important to highlight the following observations of Pleurotus cystidiosus cited from Mexico: Sobal et al. (2007) listed a strain (CP-18) determined as P. cystidiosus from Veracruz, Mexico; however, the subsequent examination of the ITS sequence obtained from this sample confirmed its identity as P. smithii and no P. cystidiosus (Huerta et al., 2010). On the other hand, Camino-Vilaró et al. (2018) mentioned that P. cystidiosus is present in Mexico, referring to Guzmán et al. (1991). However, in this last article, these authors compared the material of P. cystidiosus from the USA with the Mexican material of P. smithii, the reason why in the present work, the occurrence of P. cystidiosus in Mexico is confirmed and supported by barcode sequences.

The species exhibits a broad geographical range, as it has been documented in numerous countries across the Americas, Eurasia, and Africa (Miller, 1969; Jong and Peng, 1975; Stalpers et al., 1991; Zervakis et al., 1992; 2004; Capelari, 1999; Stajić et al., 2003; Lechner et al., 2004; Hussain et al., 2015; Shnyreva and Shnyreva, 2015; Camino-Vilaró et al., 2018). Nevertheless, some reports lack barcoding sequences, such as the ones from Argentina (Lechner et al., 2004) and Brazil (Capelari, 1999). Barcode sequences are necessary to assess the global distribution of the species and validate the unsequenced Pleurotus species from Mexico. Pleurotus cystidiosus has been found on various hosts or substrates, including Ficus carica L., Populus deltoides W. Bartram ex Marshall, Liquidambar styraciflua L., Quercus texana Buckley, Acer rubrum L., Zerkova serrata (Thunb.) Makino, Aphananthe aspera (Thunb.) Planch., and Koelreuteria henryi Dümmer (Zervakis et al., 1992). Our material was collected from an Ulmus sp. tree. All this suggests that P. cystidiosus exhibits a wide host compatibility, indicating its ability to decompose various wood substrates.

From a biotechnological perspective, P. cystidiosus is a poorly studied species worldwide, unlike other species of the genus. Among the available studies, some carbon sources, different temperatures, and culture media have been evaluated, resulting in sucrose and 28 °C the best; and all the culture media evaluated showed no significant differences in mycelial growth (Hoa and Wang, 2015). In addition, various agroindustrial waste materials, including sugarcane bagasse (SB), corncob (CC), and sawdust from Acacia sp. wood, have been demonstrated to be effective for production of fruiting bodies; the most favorable outcomes were observed when using SB and CC (Hoa et al., 2015). Hoa et al. (2017) found that total phenolic contents and antioxidant activity depended on substrate formulas and drying methods. García et al. (2020) obtained a good amount of total phenolic contents and high antioxidant activity in P. cystidiosus extracts.

Despite the information shown above, there are no studies on the content of chitin, chitosan, or any other polysaccharide or metabolite with biological activity or biotechnological potential. For the previously mentioned reasons, this is an opportunity to take advantage of our fungal resources in Mexico's arid and semiarid zones.

Conclusions

Pleurotus cystidiosus has a wide distribution and host range, and it can be mistaken for P. smithii. However, the presence of pleurocystidia in young states and long cylindrical cheilocystidia in the teleomorph of P. cystidiosus, separates it from P. smithii and other members of Coremiopleurotus. ITS barcode sequences are effective for the identification of these closely related species. The number of Pleurotus species known from Mexico rises to eight.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)