Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Estudios fronterizos

versión On-line ISSN 2395-9134versión impresa ISSN 0187-6961

Estud. front vol.17 no.33 Mexicali ene./jun. 2016

Articles

Geopolitical representation: Chile and Argentina in Campos de Hielo Sur1

Karen Isabel Manzano Iturra*

* Universidad de Concepción. Address: Víctor Lamas #1290. Concepción, Región del Bío–Bío, Chile Email: kmanzano@udec.cl

Received: March 11, 2015.

Approved: October 1, 2015.

Abstract

From a concept first articulated by Rudolf Kjellén in 1917, geopolitics has continuously evolved up to the present. The incorporation of the initial representation has been of vital importance in the analysis of different territorial conflicts. Through a geopolitical analysis, this article aims to understand the geopolitical representations in the area of the Campos de Hielo Sur, the last boundary issue that remains pending between Chile and Argentina, in addition to the manner in which both countries have debated this issue, on the basis of a number of representations in which maps have generated the image of one state facing the other, thus privileging competition between them.

Keywords: geopolitics, representation, conflict, maps, image.

Introduction

Since the establishment of the first Spanish settlements on American soil, drawings of the Southern Cone have evolved, depicting an area ranging from a few miles to its full extent, depending on the number of voyages and explorations performed in each region. In this manner, the vision of the continent as such emerged, being completed only in the nineteenth century with the British expeditions in the southern channels. For centuries, Patagonia was a place that was unexplored by Europeans, who had only been to these areas by ocean expeditions (Sarmiento, Ladrillero, Malaspina, Moraleda) to explore coasts and islands. Only some went into the forests (such as the Jesuit missionaries, from Chiloé to the area of Nahuel Huapi Lake, today's Bariloche). Further south, however, the weather itself blocked access to the mountain range. Therefore, more remote areas were not discovered until the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when Chile and Argentina were already in the midst of boundary disputes. One of these areas was called Campos de Hielo Sur or the Continental Ice Field.

The Campos de Hielo Sur is an invaluable strategic site from the geopolitical perspective, especially due to the natural resources it contains, which are essential for the future of neighboring states. As a result of phenomena such as climate change's global effects on various regions of the world, whose most visible consequence is the loss of water supplies in several places due to decreasing rainfall and ongoing anthropic exploitation, areas where water resources are found are becoming vital regions for the states' strategies. Undoubtedly, this area under border dispute is a region of the world whose potential is important not only for economic and energy development but also for the needs of the region's population.

Given these circumstances, it is necessary to analyze and understand the representations that have arisen in this particular space by referring to the existing maps that have been generated for decades by both countries. Through these maps, one can perceive the interests of the involved actors and their main objectives in this area, leading to the generation of these maps, which contradict each other with regard to a particular location. This article analyzes a series of maps, found on public websites and available to the general public, of Chile, Argentina, and the Continental Ice Field or Campos de Hielo Sur, in addition to primary, secondary, and tertiary written sources, especially in research fields such as geopolitics that attempt to answer questions regarding the continuous mapping of a remote area and that can provide valuable clues in the analysis of Chilean–Argentine projections in the southern zone.

Geopolitics and representation

In the development of geopolitics, territory has always been a key tool for analysis for the German classical school, the new French school, and Anglophone criticism. It has been a fundamental element since its origin because it was the site of the development of the only actor of the time: the nation–state. Geographers initiated the first studies that gave form to the new discipline, whose name was used by Rudolph Kjellen in 1917. The main schools were developed in Europe, focusing on the work of geographers such as Frederich Ratzel and Paul Vidal de la Blanche, who influenced the German school and the French school of geopolitics, from determinism to possibilism. Meanwhile, in England and the US, these ideas were consolidated through the heartland theory of Halford Mackinder or the role of sea power by Alfred Thayer Mahan.

After the end of the German school, Yves Lacoste (1990), representing the new French school, stresses the significance of territory in his analysis of the subject, noting that geopolitics cannot exist without geography, given that both are complementary and assign a central role to geography. The author explains that there are several levels within geography. One of them is "the General Staffs", which are groups who, by using geography and their knowledge, can use it as a tool of power economically, politically, and militarily. According to Yves Lacoste, this idea is central in geography, contrasting with the smokescreen remaining in education, where the characteristics of a geopolitical region or the so–called geopolitics of professors are repeated over and over. According to this author, in his classic text, Geography serves, first and foremost, to wage war (La géographie, ca sert d'abord à faire la guerre):

Explaining from the start that geography serves first to wage war does not mean that it only serves to conduct military operations. It is also useful for organizing territories, not only in anticipation of battles that must be waged against a given opponent but also to better control men over whom the state apparatus exercises its authority (Lacoste, 1990, p. 7).

Since the early empires of antiquity, geographers have always served the greater interests of their state or city,2 providing valuable information from their travels to certain territories they had closely observed to deliver their knowledge through their stories and maps. This practice provided a pathway for future campaigns and military invasions that would move on safe ground because they entailed knowledge of the characteristics of the geography, peoples, and wealth that these lands possessed. This phenomenon can be observed in the first classical works, such as The History of Herodotus of Halicarnassus, divided into nine books, where the first sections presented the Greeks, the ancient world, their traditions, and their wealth.

Based on this logic, countries understood the significance of projecting themselves according to the maps that they generated. These constituted a "tool of scientific information and political manipulation, a material for geopolitical critical analysis" (Goudin, 2010, p. 142) in which both countries' mentality (before the world) and their valuable areas (projections) could be observed. Maps claimed certain territories lost in war or over which countries were interested in having control3 to ensure the effectiveness of their rhetoric before others, especially focusing on their nearest neighbors or on the region where they were located, either through expansionism or through the defense of another country's interests. Mapping was performed based on the idea of the French representation, for certain purposes. It is an example of evidence that must be considered with a critical eye because it was not created innocently by those who requested it but according to the nation–states that generated them to show their intentions, actions, and main objectives. Maps provide valuable information on their interests and are also grounds for geopolitical analysis, which may be used in times of both peace and conflict, in which a certain actor can be destabilized through this system and an image of victimization before others can be generated.

Undoubtedly, a territory generates certain conditions for the countries involved because "a territory is a space appropriated and occupied by a group that understands it as part of its identity" (Goudin, 2010, p. 291). Therefore, for this group, it will be an element of unity, pride, frustration, or sadness, from the imperial maps of the greatest extension to those representing a sense of grief or sadness, regretting the glorious past, because different wars or signed bilateral treaties ended up undermining the action of the state over its original space.

Within this context, the concept of representations stands out, with Yves Lacoste determining that all geopolitical dilemmas entailed these terms, influencing how the actors see each other. Among representations, the following elements can be found:

a) Actors: they are able to mobilize resources in the international system, they are active entities in a territory, and their cooperation and confrontation are the result of their interaction with others.

b) Power: geopolitics is politics relative to the political space within which power moves to win the will of another. Power relationships can be conducted either for protection, conquest, or reinforcement.

c) Space: this is where actors are mobilized, in addition to the physical place where power is developed. It is composed of nature and society. Conflict is an essential element of geopolitics that does not exist without a space.

The notion of representation that emerges from this triad of elements extends beyond the reality of the events, given that it incorporates images and the perception of others through mapping, establishing the ways in which each country views itself and its surrounding. Perception means the "integrative process by which stimuli are interpreted by the individual; such a process occurs as a result of the integration of facts that are a stimulus, together with prior knowledge and the actor's beliefs" (Herrero, 2006, p. 143). Thus, based on these maps, together with the number of judgments surrounding the states' actions, it is possible to establish certain parameters that become perceptions, generating a vision of winner or victim that can be taught to people through images and in which maps acquire vital importance. Thus arises the notion of the imaginary, which can be understood as:

A set of mental pictures providing a meaning and coherence to an individual or a group in terms of location, distribution, interaction of the phenomena in the area. The imaginary helps organize spatial conceptions, perceptions, and practices (Debarbieux citated by Claval, 2012, p. 32).

Both concepts are fundamental for understanding the views that arise in countries in relation to others; they generate images around a specific territory. Paul Claval, one of the greatest exponents of the French School, considers that "an imaginary restructures individuals' representations of the outside world and the images nurtured by dreams and fantasies" (Claval, 2012, p. 30). Therefore, from the states' stance, an image must be provided so that people can identify with a place or territory. Certainly elsewhere, the influence of society affects the views of regions. However, when these are remote, a stable bond must be created, generating two imaginaries: a centralized imaginary, dependent on the highest authorities of the involved countries, and a regional imaginary, where nearby inhabitants defend their own connection to that place. From Vincent Berdoulay's perspective, "the growing search for affiliations and identity symbols of certain populations generates a magnifying mirror" (Berdoulay, 2012, p. 60). Representations reflect these images not only in official documents such as maps but also in extra–official documents where one can observe how cartographies are transferred to different groups of society and how these cartographies are generated around different border issues. This phenomenon creates a sense of association with the disputed area and defense of the territory against other states. As understood by Nogué, "the generation of a social or collective imaginary that comes from an intrapersonal communication process represents the first level of communicational interaction possible" (Nogué, 2012, p. 130). Thus, the following can be understood:

Actions associated with the definition of the territoriality of the nation were –and are– largely subjective, with intention and purpose, all projected from a social structure, usually linked to values forged from the sphere of power. Thus, these values are not, tabula rasa, without physical space, without a character or a social body of power that backs them up (Laurin and Nuñez, 2013, p. 86).

Therefore, these representations, which gather both images and imaginaries belonging to areas that are under dispute, are part of a certain conception of space that is associated with a particular state or country or a group of people who feel identified with a place. This phenomenon is a subject that has also been analyzed in the school of critical geopolitics, whose authors suggest the role of discourse. John Agnew refers to the subject of space, defining it as the "territorial trap", which can be understood as "the historical projection of a world in which power over others is seen as something that is split between similar entities of territorial sovereignty" (Agnew, 2005, p. 57). In other words, it is a space that is partitioned into different countries and therefore involves the generation of border issues when their interests interfere with those of their neighbors, who are interested in establishing and developing their power in the same geographical context. Therefore, both of the ideas of French geopolitics, the map game and the imaginary, are associated with the territorial trap set by critical geopolitics because they attempt to answer the same questions: why are states interested in projecting their power in a particular place by risking disputes with others when these can be resolved through discussion or confrontation? However, they correspond to what they hold in their interior, forming the basis of geopolitical representations.

The map game and traps would be meaningless if there were some preconceived idea of the power that is intended to be shown. Thus, representations are vital, and maps are a useful tool to be developed. Undoubtedly, although critical geopolitics focuses more on discourse than on geography, the contributions of maps are very useful, given that they complement the ideas of representations with projections in a particular place. Maps would not be significant if they did not search for something in the territory, either natural resources that states attempt to extract or places where they mobilize their discourses.

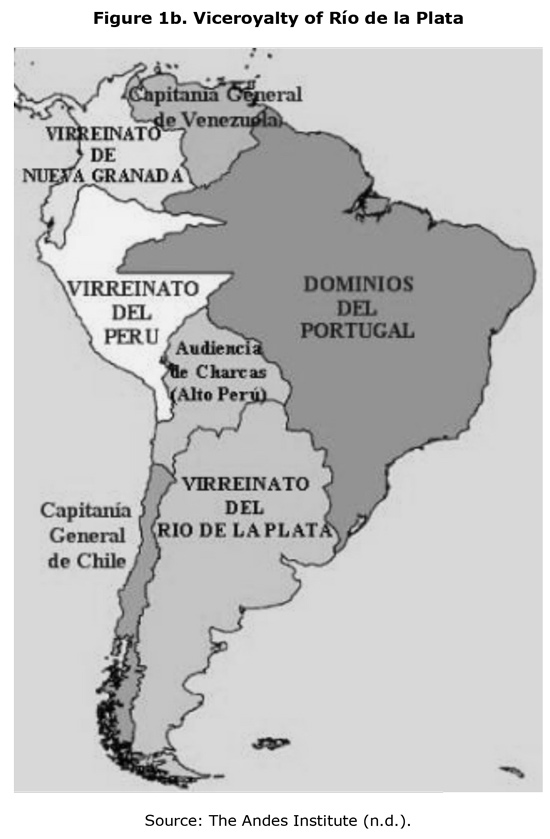

Based on this analysis, Latin America has not escaped this situation, especially when new states achieve independence, demanding the colonial legacy of uti possidetis or the old Hispanic boundaries in their respective countries, which harms discussion instead of favoring understanding. This guiding principle for nations was decided on at a time when large areas remained unoccupied by central governments. The reality showed that urban centers were miles apart, given that colonial authorities did not ensure the full control of each viceroyalty, governorate, general captaincy, and audience. At that time, the value of applying this principle was unclear. It was later understood that it would have implications for diplomatic relations by gathering these miles within one's jurisdiction, claiming these empty spaces to extend power using the same legal elements of uti possidetis.

In addition to this issue, over the years it was discovered that there was a duality of maps and images, raising a series of questions for governments. It was thus the beginning of a period of conflicts that included wars between several states,4 diplomatic offensives in international tribunals, and current territorial claims.

The inaccurate cartographic documentation of the time also responded to a certain indifference of the Spanish kingdom regarding control over the territory and greater concern for the domination of subjects as remnants of the concepts of the inherited power of feudalism (Lucero, 2007, p. 18).

That is, given that each territory was under the same authority, it was not necessary to set clear criteria for fixing the boundary. These problems were inherited by the new states when they sought to establish their boundaries. Chile and Argentina were mobilized in this context of images throughout their bilateral relationship, by retrieving old colonial data, to secure their position towards the other and thus produce a series of expectations both inside and outside their borders.

Opposed Chilean–Argentine maps

Since the nineteenth century, especially when the first theories concerning the Chile–Argentine claim for the Patagonian area started, a series of ideas were considerably developed, motivated by the founding of Fort Bulnes in the Strait of Magellan. Argentina formally complained to Chile regarding this act because it considered that this site was in an area belonging to Argentina. It was then that different colonial maps that played off the views of both countries, claiming the Magellan areas and the southern passages by using the same tools, began to be used.

As the basis for its claims, Chile started to use the map of Cano and Olmedilla (1775), in which the General Captaincy was represented with a jurisdiction that extended across the Andes from the Diamante River to the south, including a wide area corresponding to Patagonia. This map provided for complete domination over the Southern Cone of South America and the bi–oceanic corridor (Pacific–Atlantic), which was replicated in subsequent maps. This map had detractors, given that it had not updated the administrative divisions of the Bourbon period, which the following year established the creation of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata from the governments of Paraguay, Río de la Plata, the Real Audience of Charcas, and the extraction of the provinces of Cuyo, San Juan, and San Luis, which up to that point had belonged to Chile but were now transferred to the new administration. Despite this situation, the idea of the Diamante River as a boundary of the southern edge of the Chilean territory was further developed.

Meanwhile, in Argentina, other types of maps and documents were used. One of the most significant and most commonly used maps, that of D'Anville (1748), granted to the governorate of Buenos Aires the ownership of the Patagonian coasts and the mainland divided by a borderline "with one–third for Río de la Plata and two–thirds for the Kingdom of Chile" (Lacoste, 2004, p. 225). This cartographic representation marked the development of maps in Argentina during the nineteenth century that granted an idea of ownership over the southern regions. In addition to representations, one of the most significant documents dating from the period before the foundation of Buenos Aires was the Royal Decree of 1570, which defined the limits of the jurisdiction at the time. It had been granted to Juan Ortíz de Zarate by King Philip II, whose purpose was to "move the southern border of the Governorate of the Río de la Plata from the meridian 36° 57' to the latitude of 48° 21' 15" south (Lacoste, 2002, p. 217). It followed the concession of the slice of territory to Simón de Alcazaba and Pedro de Camargo,5 who could not effectively control the involved areas but only undertook partial recognition, at a time when the cartography of South America was itself not complete. However, this Royal Decree also did not generate significant changes because the conquest concentrated on the inland areas and along the coast; the foundation of Buenos Aires was determined later (1580).6

During the conquest period, the Governorate of the Río de la Plata had jurisdiction over the territories of the eastern part of South America. However, in Patagonia, the territories were considered "as desolate territories, lacking wealth and unsuitable for European settlement" (Lacoste, 2002, p. 224). Therefore, there was no real interest in the area, which was far from the focus of attention. However, these titles were used in the studies of Pedro de Angelis and Dalmacio Vélez Sarsfield, who, beginning in the 1850s, began to claim the rights of Argentina in the Patagonian and southern zone. This action resulted in the beginning of formal claims for the southern part of the Southern Cone and for regaining the titles preceding the emancipation process as a basis for these theories. However, it did not only occur in Argentina. During the same period in Chile, Miguel Luis Amunátegui and Carlos Morla Vicuña conducted research on the territory in Patagonia. The latter author found evidence of the Royal Decree of 1570 but failed convince, given that data were found in the 1680 compilation of The Laws of the Indies (Leyes de India). Amunátegui explained the following:

The entire kingdom of Chile, with cities, towns, places, and lands that are included in the administration of these provinces, in addition to what is now peaceful and populated and what was reduced, populated and pacified inside and outside the Strait of Magellan and inland to include the Cuyo province (Amunátegui 1880, pp. 34–35).

In 1810, these boundaries left Patagonia under Chilean, not Argentine, jurisdiction because the king had failed to mention Tucumán, delivered to the Charcas audience in 1563. Therefore, he understood that this document was no longer valid during the independence period. These differences of opinion continued to be developed from then on and to be reflected in the production of maps that were at odds regarding the same area, Patagonia, and thus the future ownership of the Campos de Hielo Sur. In that sense, one can understand that:

At that time, the vagueness in plans was the result of an age where vast tracts of unexplored lands permitted the existence of inaccurate maps, without this being the main cause of clashes in this hemisphere. In other words, at that time, mapping was quick, due, first, to ignorance regarding the territory, given the precarious transport, and second, to the lack of appropriate technologies for precise topography (Lucero, 2007, p. 18).

For centuries, these uninhabited areas of the Southern Cone were not a concern for the states that claimed them. Only the coasts had piqued Chile's interest, whereas for Argentina, occupation by means of campaigns against the indigenous people occurred in this region. It can be considered that the geopolitical rivalry of both countries began in that period, given that images of Patagonia showed this space to belong to only one of the parties involved and were replicated on many occasions. This phenomenon led to a series of prejudices within the population, favoring views of competition between states rather than possibilities of mutual integration. In this sense, transposing territories becomes important. That there were contradictory maps helped cast doubts in people and other countries in the world that did not know the root of the problem but that were guided by the quantities of evidence or the existing maps regarding a particular territory. Thus, they could end up supporting or condemning the actions of one state against another, acquiring a strong political and diplomatic composition (see Figures 1a and 1b). The reason is the following:

In this sense, cartographic production, and its objectification in defined maps, plays an active role in the relational configuration of space, and owing to a mechanism of recurrent causality —that is, the appropriation and regular use of given created maps— it reproduces an image of a determined world, erases traces of its genesis, and defines modes (Aguer, 2014, p. 131).

The figures presented above are maps found on public websites that show the views outlined above. They were key to the Chile–Argentina relationship. They show areas where each state had a particular projection and how this imaginary was transferred to a general population that does not have the means to view the official maps but that can view those on easily accessible websites. In the case of both countries, one can observe the idea of glory at a particular moment in time in its history, with a vast extension of territory under its control, which is currently limited, in large part because of the other country's actions. The representation of the expansionist neighbor was thus generated, impeding the other country from maintaining that unity, resulting in the reduction of its natural spaces. Patagonia, the interoceanic passages, and the Andean southernmost glaciers were repeatedly found in the same situation in maps where Chilean and Argentine jurisdictions are opposed and that are made known to their inhabitants, reaffirming the process of imaginaries that surround geopolitical representations.

Campos de Hielo Sur or Continental Ice

Patagonia has been under dispute since the mid–nineteenth century. Negotiations were stalled, especially after a series of authors, whose writings favored their respective governments, suggested that both sides of the mountain range must defend their own state at all costs. The first treaty that focused on border issues dates back to 1856, when Chile signed an agreement with the Argentine Confederation7 that stated the following:

Article 39º. Both contracting parties acknowledge the boundaries of their respective territories, those they possessed as such at the time of separation from Spanish domination in 1810, and they agree to postpone issues that arose or may arise on this issue for some future peaceful and friendly discussion, without ever resorting to violent measures; and in the event a full agreement is not reached, the decision must be submitted to arbitration by a friendly nation (Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Commerce, and Navigation, 1856).

Evidently, the principle of uti possidetis was noted again, postponing border issues, especially after publications that began to arise regarding the rights over Patagonia that, on both sides of the Andes, praised the maximal thesis of domination of belonging to Chile or Argentina. Amunátegui, Morla Vicuña, Vélez Sarsfield, and Quezada defended their principles in favor of their own countries, finding both admirers and detractors of their policies, but their maps began to be widely recognized in academic circles. In those circles, the control of the Southern Cone, whose sovereignty gave access to the bi–oceanic corridor and maritime passageways at a time when boat traffic was conducted from the south, was the most important geopolitical area to claim. The representation from that period continued to influence subsequent governments:

The definition of territoriality of the nation and of the border was a process of space configuration, which was not only a physical or geographic issue, i.e., annexing land and defining the territorial limit was a scene with a relevant social background, as determined social relations (social agents) in turn involved spatial relations (Laurin and Nuñez, 2013, p. 86).

The behavior that both governments developed gradually determined the bilateral relationship, and tensions motivated an intervention to avoid conflict, which had been feared since the incidents of Jeanne Amelie and Devonshire,8 generating uncertainty with regard to a possible military conflict, especially in 1878. At the end of that year, this situation led both countries to commit to finding a solution to the border issue in the Fierro Sarratea Treaty, in which "the Republic of Chile shall exercise jurisdiction over the sea and the coast of the Strait of Magellan, channels, and adjacent islands and Argentina over the Atlantic sea and coasts and adjacent islands "(Barros, 1970, p. 353). This agreement laid the foundations for a subsequent treaty in 1881. This document, signed in the midst of the actions of the Pacific War, clearly defined the following:

Article One: The boundary between Chile and the Argentine Republic is from north to south to the parallel of latitude 52°, the Andes. The boundary line will go along that extension through the highest peaks of this mountain range, dividing the waters and passing through the slopes emerging at each side. The difficulties that may arise, given the existence of certain valleys formed by the bifurcation of the Andes, and where the watershed is not clear, shall be amicably resolved by two appointed experts, one from each side. In the event that an agreement fails to be reached, a third expert will be appointed by both governments to make a decision (National Office for Borders and Limits of the State [Dirección Nacional de Fronteras y Límites del Estado – DIFROL], 1881, para.5).

This article contained some issues. The Andes consisted of a great mountain range in most parts of the boundary where the borderline of the high peaks and the watershed completely coincided. However, to the south, both geographical principles were completely dissociated. Doubts emerged regarding the vital basis of separation and demarcation where Chile acknowledged the divortia aquarum (watershed in the Atlantic and Pacific sides) and Argentina acknowledged the continental divortia aquarum (watershed through the high peaks), given that this border could ensure more square kilometers. In the case of the high peaks, the region of Aysén and Magallanes has a key geological formation: the southern Patagonian mountain range, part of the Andean chain, which was recognized in the northern section by the Italian explorer Alberto de Agostini "for the extraordinary development of its ice field that covers its highest areas as a huge mantle" (Agostini, 1945, p. 7), with important heights that stand out, such as the hills of San Lorenzo (4 050 m) and San Valentín (3 700 m). Further south, the most significant mountain landscapes are Mount Fitz Roy and Cerro Daudet, where a great number of glaciers can be found, such as the large ice field, known as the Continental Ice Field in Argentina, which descends towards both sides of the southern mountain range. This definition was questioned because it was considered that given its size, only those located in Greenland or Antarctica could be characterized and that "this region does not show the proper geographical characteristics of a Continental Ice Field, hence the definition of Southern Continental Ice Field chosen by Chile is the most appropriate" (Lucero, 2007, p. 51).

Geographically, the Ice Field extends from "latitude 48° 15' South to 51° 35' South and from longitude 73° 00' to 74° 00' West. It covers an area of 13,900 km², of which more than three–fourths belong to Chile. A minor part of the Campo de Hielo Sur has a border with Argentina" (National Congress, 2009, p. 8); thus, its existence is relevant in the southern water system. According to a study by Börgel, it "feeds several stretches of the glacier flowing into the Pacific Ocean, falling from cliffs, in addition to the east, into the Argentine lakes" (Börgel, 1995, p.10). The author even confirms that among the ice caps, "this is the third largest after Antarctica and Greenland" (Börgel, 1995, p. 10), transforming this place into an important reservoir of solid water globally. It is considered to be a remnant of a large mass of ice that existed 100,000 years ago in the Southern Cone whose thickness, close to 1000 m, became an obstacle to determining any division. Although there is a prominence at the base of the glacier, ice will cover it if it is not also reflected on the surface of the glacier. Most basins flow into the Pacific Ocean, and only two, the Viedma and Argentino lakes, are on the Atlantic side. The biggest issue arises in the mountain chains because "it has two lines of high peaks, one on the edge close to the Pacific Ocean, and the other one on the eastern edge, above the lakes and plateaus of the Argentinian pampa" (Börgel, 1995, p. 12). Thus, the dilemma has always been to define which sector is the most important for demarcating the Chile–Argentina border, which was reflected in their respective maps.

Representations

With the definition of the central geographical aspects of the region, it can be observed that from the beginning of diplomatic relations, both Chile and Argentina have worked according to overlapped maps, which were exploited by the most nationalist groups to continue making territorial claims.9 After signing the Treaty of 1881, with the establishment of the final boundary, the generation of these maps with the same problem did not stop. These maps justified a number of new explanatory agreements, such as that of 1893 regarding the bi–oceanic principle, and negotiations to solve issues related to the dividing line in the southern area.

Campos de Hielo Sur began to appear on maps after the demarcation of the land border, which raised new questions. Thus, it became necessary to resort to a foreign power that served as the arbitrator in these cases. The expertise of Moreno and Barros Arana in 1898 was published in a report that stated the following:

Art.1–.That, as a result of the comparison of the general border by the Argentinian Expert set in the act of last September 3, and of that presented by the Chilean Expert set in the act of August 29, that the areas and stretches of the first marked with numbers (...) 304 and 305 are consistent with the points and stretches of the second marked with numbers (...) 331 and 332; they resolve to acknowledge them as being part of the borderline in the Andes, between the Argentine Republic and the Republic of Chile (Lucero, 2007, p.22).

The act established that the boundary in the region covering the Ice Field was drawn as a straight line dividing the glaciers between the states because, as explained above, the points were agreed to by both experts; thus, it was clear that the case was considered closed. Subsequently, following the judgment by His Britannic Majesty Edward VII in 1902, Patagonia was divided. In the case of the Great Lakes, these acquired a bi–national character, given that the boundary line passed through the middle of them, granting half to Chile and another half to Argentina. Argentina was granted rights on all areas that it had begun to occupy. The implication was that "the referee is in the presence of faits accomplis" (Orrego, 1902, p. 182). Therefore, he acknowledged all the colonies that had already settled in Patagonia before the existing treaties where people felt identified with Argentina. However, in the case of the territory of the Campos de Hielo Sur, it was separately established in one of the articles that the area had already been demarcated by mutual agreement of the involved parties, as shown in the following extract of the Arbitration Ruling of 1902, which, after marking the division, determined the following:

Article III (excerpt) The further continuation of the boundary is determined by lines that we have set across Buenos Aires, Pueyrredon (or Cochrane), and San Martín Lakes; thus, the western portions of the basins of these lakes are assigned to Chile and the eastern portions to Argentina, as the high peaks called Mount San Lorenzo and Fitz–Roy are on the dividing lines. From Mount Fitz–Roy to Mount Stokesthe, the borderline was already determined (Errazuriz, 1968, p. 108).

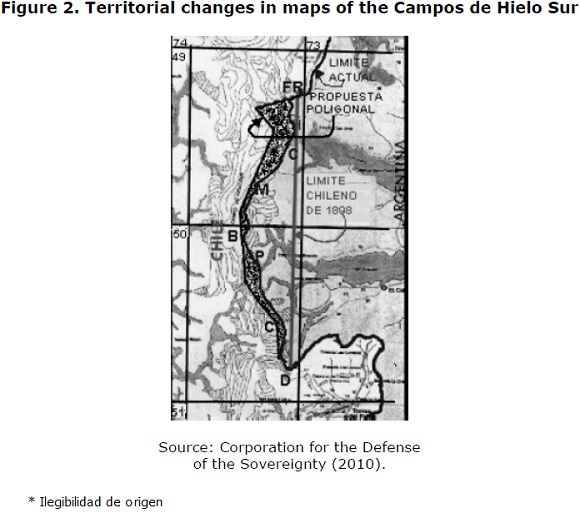

Figure 2 is a map generated in Chile by the Corporation for the Defense of Sovereignty (Corporación de Defensa de la Soberanía), and it shows the evolution of the territorial limitation at this point from a line that marked the border in 1898 until the moment when a series of corrections referring to subsequent agreements reached in the twentieth century, changing the boundary in that region, were made.

This generation of images that can be found on the Internet undoubtedly highlights the most conservative Chilean position regarding the issue. This position arises as a result of the geographical interpretations of the area, where Chile recognized the eastern mountain range as a demarcation line. However, for Argentina, the western section was transformed during separation into an environment covered with ice that hampered field research, which was reflected in all the documents in which that place was noted, creating double boundaries. According to Rosa (1998), problems arose in the mid–twentieth century:

Divergences on the boundary demarcation in the Ice Field sector took shape when they began to appear in official maps of both countries over the years. (...) In the northern portion, they coincided until 1953, when the first Chilean maps were published, supported by aerial photographs taken by the US in 1947. These maps partially diverged from the criteria of the continental watershed. Since then, the discrepancy increased (Rosa, 1998, p.140).

Undoubtedly, this situation provided a geopolitical representation in which Chile became a "great competitor" in the Patagonian region, especially in the province of Santa Cruz. Here, General Juan Enrique Guglialmelli described the situation that Argentina found itself in, after analyzing Chilean demographic pressure, as: "finally, from the geopolitical stance, another special circumstance must be mentioned: the perspective that the entire province is transformed in the short or medium term into a border with high levels of tension" (Guglialmelli 1979, p. 261). His words clearly relate to the crisis of the Beagle Channel, which both nations faced in those years. However, it certainly helped understand that Patagonia, where the Campos de Hielo Sur is located, was constantly pressured by Chile, generating an imaginary around this idea.

When the demarcation became an inseparable issue, especially for the amount of maps that the same sector represented in different hands, the work of the Joint Commission became essential. Given that no satisfactory agreement was reached between the delegations of both countries, bilateral talks were conducted at the presidential level. The first attempt was made in 1991, when the first polygonal line was established in the region of the Campos de Hielo Sur, whereas the fate of Desert Lake was left in the hands of a Latin American Tribunal. This agreement created problems in both countries. According to Chile, it was alleged that the territorial limitation had already been clear since 1898, whereas in Argentina, the difficulties were concentrated in the province of Santa Cruz, where people saw that this agreement reduced their territory. This situation shows that there is a double representation of the issue within Argentina: a provincial side, which views these agreements with Chile as a risk, and a central side, where this borderline helped arrive at a swift agreement favoring commercial zones and the Common Market of the Southern Cone (MERCOSUR). The reason is, on the Argentine side, the region is more populated than it is on the Chilean side. Meanwhile, there is a very similar view in Chile. Although some sectors and people in the Aysén region recovered the borderline, the central government's decision was held to achieve the setting of a new borderline. The government's attempts were consolidated by the 1998 Agreement (DIFROL, 1999), establishing that the final territorial delineation would be left in the hands of a Joint Boundary Commission in charge of drawing the borderline between Cerro Daudet and Mount Fitz Roy, the last points under debate, guaranteeing the sources of the Santa Cruz River to Argentina, provided that:

For the demarcation on–site, the Parties mandated the Chile–Argentina Joint Boundary Commission, as provided in the Protocol of Replacement and Positioning of Milestones in the Chile–Argentina borderline (Protocolo de Reposición y Colocación de Hitos en la Frontera Chileno–Argentina) of April 16, 1941, and in the Action Plan and General Provisions (Plan de Trabajos y Disposiciones Generales), for conducting surveys to jointly prepare a 1: 50,000 scale map as a prerequisite for performing the aforementioned demarcation (DIFROL, 1999, para.12).

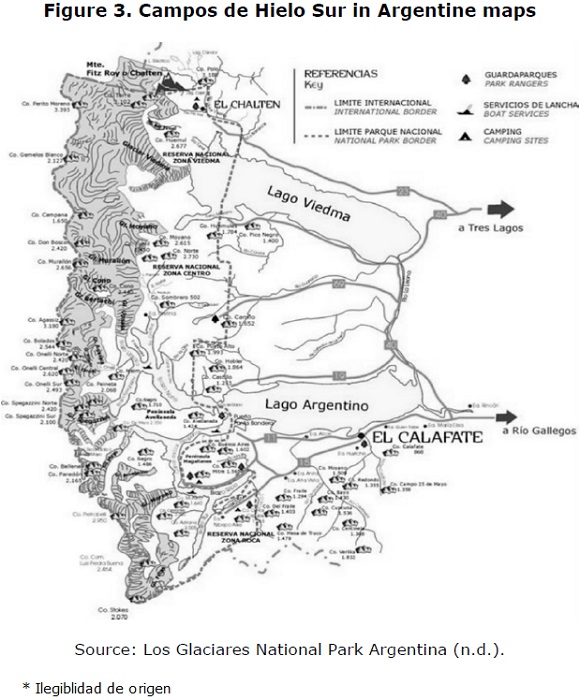

When analyzing the behavior of each state, it can be understood that both continued generating maps. Owing to its advantageous territorial position in the bordering area, Argentina managed to obtain a flat area, as opposed to the rough terrain on the Chilean side. It generated a series of images in the tourist services network around the Continental Ice Field including Los Glaciares National Park, especially in areas close to the cities of El Chaltén and Calafate, which in turn highlighted the potential of the region but omitted the point under debate with Chile. These maps (see Figure 3) were released on different tourism websites, and they certainly do not help generate understanding.

One of these tourist maps, widely shared in social networks and in the international media, corresponds to a page dedicated to glaciers and precisely notes Los Glaciares National Park as one of the most important tourist circuits in the province of Santa Cruz, where the boundary under development with Chile is marked. As stated by Yves Lacoste, the idea of manipulating maps is something entirely feasible, especially in areas of low population density and difficult access, as in this case where, on the Argentine side, the disputed area is not noted. On the other hand, in Chile, the opposite occurred because, in various instances, it is indicated that the dispute remains, using a blank box that notes the 1998 Agreement (DIFROL, 1999), specifying that it will continue to appear until the work of the Joint Commission of both states is finished. Therefore, the presence or not of this box that highlights the border issue is also part of the states' discourse, generating an international perspective regarding the issue. The existence of extensive tourism and images regarding the appropriation of the glaciers creates a perception that is contrary to the resolution of the border dispute, with Argentina having managed to supersede Chile in creating a large number of images in the involved region.

Current cartography

This situation described above shows that divergences regarding images and maps have continued despite the existence of new agreements. This situation has been possible to observe in the twenty–first century, and thus, the practice of geopolitical representation has continued its actions in the southern zone. One of the last discrepancies occurred in 2010, when the Chilean press published an Argentine map in which the 1998 Agreement was ignored and in which the work of the Joint Commission and the points that were defined were not explained. However, this incident was not the first with regard to this issue. Previously, it was reported that in

2006, after the publication of maps by the Ministry of Tourism of Argentina, which did not conform to what was agreed by both countries, by showing the northern region of the Continental Ice Field as a pending demarcation, Chile submitted an official complaint to the Argentine government (Eissa, 2005, p. 55).

Since 2010, and considering the situation described above, a series of crisscrossing declarations has begun, showing the annoyance of the Chilean government in light of signs that this agreement was not being respected by its counterpart. It even added more square miles to a problem area confined to area between Mount Fitz Roy and Cerro Daudet. From the geopolitical stance, these images respond to the context of representations where a state seeks to reflect to the world its control over certain areas through the use of different media (see Figure 4).

The above maps, published in the Argentine newspaper Clarin, showed two versions and caused a commotion in the press of both countries. They had an impact on the political arena. On one hand, they showed the image of Chilean texts using a blank box to demarcate the area to be delimited, whereas Argentine tourism companies echoed official documents to mark the extension of Los Glaciares National Park and in which the border line under discussion was in no way noted. These maps generated the idea that "the establishment of a new borderline by Argentina goes against the predetermined agreement on an area that is still kept pending and that Buenos Aires entirely assumes as its own" (Faundes, 2008 p. 264). Indeed, more areas than those included in the dispute were included. The reason is water, the vital natural resources located in these glaciers, which is key to the development of people's lives, both for daily consumption and the economic activities of such great importance on the eastern side, such as agriculture and livestock, which rely exclusively at latitude on the Santa Cruz River, the main course of the region. Furthermore, their cities present with a constantly growing population that, in the near future, will need more water for its basic needs.

This situation caused tension in the good neighbor relations that had been developed since the Treaty of 1984, leading to the creation of Confidence–Building Measures in political, military, and scientific arenas, which, only a year before the appearance of this map, had been ratified by the Maipú Treaty between the governments of Michelle Bachelet and Cristina Fernández. In addition, opposed views advocated by parliamentarians have continued to be developed regarding the involved areas; for example, Senator Antonio Horvath (Chile) offers the following with respect to the Campos de Hielo Sur:

On the Chilean side, this corresponds to O'Higgins National Park and to Los Glaciares Park on the Argentine side. However, Argentinians benefit from tourism and from a reputation on the international level. In fact, they show the disputed area as their own on their maps. Once again, Chile does not have to stick with what is legal and must be peacefully present in the area with maps, documents, studies, science, recreation, tourism. And although it is harder to access, we have the same right to benefit from it (Francino, 2014, para.8).

Therefore, geopolitical representations remain present in the actions of states, which have generated images that create a vision or imaginary within the population, especially when the areas under debate are far from the most important administrative centers. In this case, the Campos de Hielo Sur meets these requirements, given that some years ago, this place was remote and unknown to people. However, maps helped to consolidate this feeling of unity with these places this, despite the fact that nearby residents, mostly on the Argentine side, also developed a sense of belonging to this area and a sense of rivalry with the State view, which can act in the interest of the national good over the regional good. Border issues will remain as long as these representations are generated. They hinder the integration processes that have been established because cartography still shows that despite advances, the mindset of competition and appropriation of this land over the other remains.

Final considerations

Geopolitics, whose origin lies in geography, provides significant insights with regard to the behavior of states that, throughout their history, have mobilized in accordance with their interests in different nearby places. In the midst of this, the idea of representation, which is ultimately the image to be projected through maps in a territory, was and will be key in the Chile–Argentina relationship with respect to Patagonia, a vast pampa that, given its latitude, is an area of low population density and rich in natural resources. Here, maps have projected an imaginary that allows the population to identify with the places that are under dispute. Undoubtedly, maps are not innocent tools because they present what a state looks like to the world, in addition to the areas that it intends to obtain or occupy in the future, against the will of its neighbors or nearest rivals. Since the first territorial claims, the maps created under the Spanish authorities were used to appropriate or demonstrate unfriendly attitudes towards the neighboring country, creating a representation where the other was an expansionist power and where doubts only led to future difficulties.

The Campos de Hielo Sur is one of the regions that meet this requirement, given that it is a largely uninhabited place on the Chilean side and with greater density on the Argentine side. It shows that a geopolitical representation was constructed over the years, and its remoteness has required the generation of an imaginary around it so that people can identify with the territorial claims of the states. This phenomenon can be observed in the large number of contradictory maps on public websites where people easily obtain information. This situation in turn leads to a view that results from what people see on these websites, given that most do not have access to documents and the official maps of each state. If these maps generate a view at the national and regional levels, they also play an important role at the international level. Therefore, the influence exerted by these images is very strong, helping create a wrong perception of reality when they fail to note the work of the boundary commissions in the area. Since the establishment of the first known boundary, the borderline has been modified several times until the last agreement, which was reached in 1998, leaving the final demarcation of this region in the hands of a Joint Commission that noted that this situation had to be marked on all official maps until the work was completed.

The latest misunderstandings arose after the publication of a map in Argentina in 2010, where the Treaty of 1998 and the polygonal line between Cerro Daudet and Mount Fitz Roy were ignored. It showed that maps with these characteristics are more common than was previously thought. The number of miles of the Campos de Hielo Sur or Continental Patagonian Ice Field was greater in Argentina than in Chile and appeared on tourism websites, whereas Chile explained the presence of a pending agreement in the bi–national Joint Boundary Commission through the use of a blank box. These issues not only led to a bilateral discussion on the territorial limitation but also led to mistrust, with Argentina using geopolitical representations to argue the division of the Campos de Hielo Sur or Continental Ice Field. Because of these representations, the perception of expansionism by one of the involved states is again imposed, given that neither the demarcation lines nor the agreement signed in 1998 are indicated.

Undoubtedly, these representations and images are central. Maintaining these maps of certain areas of a territory only shows that there are particular interests for the states involved. Therefore, it is important for them to show the world what their intentions are by using maps to produce a significant sign. This sign results in a self–perception of Chilean and Argentinian citizenship where mistrust prevails over the integration efforts that have been developed since the signing of the Treaty of Peace and Friendship in 1984 (DIFROL, 1985) and in which trust–building measures were agreed upon to move forward with a common agenda that could remedy the agreements through diplomatic means. Certainly, the wealth of this area, especially its water reserves, is key to the future development of these states. Therefore, such images only respond to the idea of geopolitical representation, where the involved states expect that their interests will be seen at an international level and which are their real future projections in these cases. Undoubtedly, although the 1998 Agreement on the Campos de Hielo Sur is applied, to date, this area's demarcation has not been completed. Although there are points on the polygonal line, the tasks within the Joint Boundary Commission have not concluded. Therefore, a series of maps that provide a geopolitical representation by Chile or Argentina, where one of the involved parties feels the other, will continue to be created.

References

Agnew, J. (2005). Geopolítica una re–visión de la Política Mundial. Madrid, España: Trama. [ Links ]

Agostini, A. (1945). Andes Patagónicos. Buenos Aires, Argentina. [ Links ]

Aguer, B. (2014). Geopolíticas del conocimiento tras la proyección Mercator. Avatares Filosóficos, (1), 130–141. [ Links ]

Amunátegui, M. (1880). La cuestión de límites entre Chile y Argentina. Santiago, Chile: Imprenta Nacional. [ Links ]

Barros, M. (1970). Historia diplomática de Chile 1541–1938. Santiago, Chile: Andrés Bello. [ Links ]

Berdoulay, V. (2012). El sujeto, el lugar y la mediación del imaginario. En A. Lindón y D. Hiernaux (Dir.), Geografías de lo imaginario (pp. 49–65). Madrid, España: Antropos. [ Links ]

Börgel, R. (1995). Delimitación en el Campo de Hielo Sur. Revista de Geografía Norte Grande, (22), 9–14. [ Links ]

Claval, P. (2012). Mitos e imaginarios en geografía. En A. Lindón y D. Hiernaux (Dir.), Geografías de lo imaginario (pp. 29–48). Madrid, España: Antropos. [ Links ]

Congreso Nacional. (2009). Informe de la Comisión Especial de Campo de Hielo Patagónico Sur. Valparaíso, Chile: Comisión Especial de Campo de Hielo Patagónico Sur. [ Links ]

Corporación de Defensa de la Soberanía. (2010). Campo de Hielo Sur. Recuperado de www.soberaniachile.cl [ Links ]

Dirección Nacional de Fronteras y Límites del Estado (DIFROL). (1881). Tratado de Límites de 1881. Recuperado del sitio de Internet de DIFROL Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores, Gobierno de Chile: http://www.difrol.gob.cl/argentina/tratado–de–limites–de–1881.html [ Links ]

Dirección Nacional de Fronteras y Límites del Estado (DIFROL). (1985). Tratado de Paz y Amistad de 1984. Recuperado de http://www.difrol.gob.cl/argentina/tratado–de–paz–y–amistad–de–1984.html [ Links ]

Dirección Nacional de Fronteras y Límites del Estado (DIFROL). (1999). Acuerdo para precisar el recorrido del límite desde Monte Fitz Roy hasta el Cerro Daudet. Recuperado del sitio de Internet de DIFROL Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores, Gobierno de Chile: http://www.difrol.gob.cl/argentina/acuerdo–para–precisar–el–recorrido–del–limite–desde–el–monte–fitz–roy–hasta–el–cerro–daudet.html [ Links ]

Eissa, S. (2005). Hielos Continentales. La política exterior argentina en los 90'. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Centro Argentino de Estudios Internacionales. [ Links ]

Errazuriz, O. y Carrasco, G. (1968). Las relaciones chileno argentinas durante la Presidencia de Riesco (1901–1906). Santiago, Chile: Andrés Bello. [ Links ]

Faundes, C. (2008). El agua como factor estratégico en la relación de Chile y los países vecinos. Santiago, Chile: Academia Nacional de Estudios Políticos y Estratégicos. [ Links ]

Francino, R. (31 de enero de 2014). Horvath advierte sobre pasividad chilena en Campos de Hielo. Recuperado de http://noticias.terra.cl/chile/horvath–advierte–sobre–pasividad–chilena–en–campos–de hielo,55fa82c4e35e3410VgnVCM3000009af154d0RCRD.html [ Links ]

Goudin, P. (2010). Diccionario de Geopolítica. París, Francia: Choiseul. [ Links ]

Guglialmelli, J. E. (1979). Geopolítica del Cono Sur. Buenos Aires, Argentina: El Cid. [ Links ]

Herrero, R. (2006). La realidad inventada. Percepciones y proceso de toma de decisiones en Política Exterior. Madrid, España: Plaza y Valdés. [ Links ]

Instituto de los Andes. (s.f.). Virrenato del Perú (01–10). Recuperado de http://gerencia.blogia.com/2015/031601–el–virreinato–del–peru–01–10–.php [ Links ]

Lacoste, P. (2002). La guerra de los mapas entre Argentina y Chile. Una mirada desde Chile. Historia, (35), 211–249. [ Links ]

Lacoste, P. (2004). La imagen del otro en las relaciones de la Argentina y Chile (1534–2000). Santiago, Chile: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Lacoste, Y. (1990). La geografía, un arma para la guerra. Barcelona, España: Anagrama. [ Links ]

Laurín, A. y Núñez, A. (2013). Frontera, globalización y deconstrucción estatal. Hacia una geografía política crítica. En M. A. Nicoletti y P. Núñez (Comps.), Araucania– Norpatagonia: la territorialidad en debate (pp. 83–100). Bariloche, Argentina: Instituto de Investigaciones en Diversidad Cultural y Procesos de Cambio. [ Links ]

Los Glaciares. (s.f.). Parque Nacional Los Glaciares Argentina. Aspectos generales. Recuperado de www.losglaciares.com/es/parque [ Links ]

Lucero, M. (2007). El poder legislativo en la definición de la Política Exterior Argentina. El caso de los Hielos Continentales Patagónicos. Cuadernos de Política Exterior Argentina, 90, 1–124. [ Links ]

Niebieskikwiat, N. (29 de agosto de 2006). Hielos continentales, reclamo de Chile por mapas argentinos. Diario Clarín. Recuperado de http://edant.clarin.com/diario/2006/08/29/elpais/p–01201.htm [ Links ]

Nogué, J. (2012). Intervención en imaginarios paisajísticos y creación de identidades territoriales. En A. Lindón y D. Hiernaux (Dirs.), Geografías de lo imaginario (pp. 129–139). Madrid, España: Antropos. [ Links ]

Orrego, L. (1902). Los problemas internacionales de Chile. La cuestión argentina, el Tratado de 1881 y negociaciones posteriores. Santiago, Chile: Esmeralda. [ Links ]

Rosa, C. L. de la (1998). Acuerdo sobre los Hielos Continentales: razones para su aprobación. Mendoza, Argentina: Ediciones Jurídicas Cuyo. [ Links ]

Tratado de paz, amistad, comercio y navegación de 1856. Artículo 39.

Zamora, J. (s.f.). Historia de las fronteras de Chile. Recuperado de http://mediateca.cl/900/historia/chile/fronteras/fronteras%20de%20chile%20independencia.htm [ Links ]

Footnotes

1 This work is part of the following thesis, "Southern Geopolitics: The case of the Campos de Hielo Sur", developed in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Political Science, Security and Defense from the National Academy of Political and Strategic Studies; the advisor is Dr. Juan Eduardo Mendoza Pinto.

2 In Ancient Greece, where the geographer was the first source of knowledge regarding remote locations. One only needs to recall The History of Herodotus, divided into nine books, whose first five contain important information on other cultures, such as Egypt.

3 The mentality of a people can be observed through its geographical location in the world; for example, Western countries, which have kept a world map where Europe is at the center. However, there are medieval maps where Jerusalem is in a privileged location due to their Christian conceptions. Regarding maps that claim lost territories, there are local cases such as Bolivia, where the map of grief was used by many governments whose lack of access to the sea was blamed in relation to the country's development issues.

4 The most controversial period was the nineteenth century, when disputes were settled through large–scale wars, such as the Triple Alliance War, where Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay confronted Paraguay (1864–1870), and the War of the Pacific, where Chile fought against Peru and Bolivia. The number of states involved in both cases and the territorial changes to the map of South America are an example of how disputes were resolved in this manner. However, the implication is not that the twentieth century was a quiet period; wars such as the Cenepa War between Ecuador and Peru occurred until the 1990s.

5 Simón de Alcazaba and Francisco de Camargo managed to induce King Charles V to hand over control of a part of South America. In the case of Simón de Alcazaba, he was made governor of Nuevo León; he was then succeeded by Francisco de Camargo, who extended this territory to the Strait of Magellan.

6 The foundation of Buenos Aires in 1580 was the second Spanish attempt in the area, after the failure in 1536 of the first coastal settlement by Pedro de Mendoza. Most efforts were developed around the city of Asunción, which became the main center of this South American area.

7 Until 1861, the Argentine Confederation and the government of Buenos Aires were separate, which was the highest point in the discussions and civil wars that the country faced in the nineteenth century. The marked differences between the provinces and the capital generated two governments after the fall of Juan Manuel de Rosas in 1852.

8 Both cases relate to incidents in the southern coast, where Jeanne Amelie in 1876 (France) and Devonshire in 1878 (United States), who loaded guano without licenses, were arrested south of the Santa Cruz River by the Chilean authorities. This action triggered major issues with Argentina, which considered that area under its jurisdiction.

9 The map effect is very important in the generation of the images of a given country because ordinary people unconsciously generate the idea that the neighboring country is an expansionist power that has removed areas that they consider legitimate and their own.

texto en

texto en