Introduction

Chagas´ disease is a protozoan infection caused by Trypanosoma cruzi that currently affects 7 million people worldwide mainly in the Americas (its endemic area) up to 30% if patients suffer cardiac complication, and up to 10% digestive manifestations that could lead to patients' death. Parasitosis can be treated in the acute phase with benznidazole and nifurtimox, in chronic cases, has no cure, but is useful to offered treatment to prevent congenital transmission1.

Congenital transmission of the infection can occur during pregnancy, childbirth, and even during breastfeeding, even in asymptomatic pregnant women. Neonates may be asymptomatic or present with edema, fever, low birth weight, cardiomegaly, myocarditis, pneumonitis, hepatosplenomegaly, and even be born prematurely2.

In endemic areas, there is congenital transmission happening even in areas where the control of the vector and blood bank transfusion is certificated by the local govern3. It is estimated that there are 40,000 infected pregnant women and 2,000 infected newborns in North America4.

There are no current data of the women childbearing infected with T. cruzi in Latin America, but as is the Chagas´ endemic area, numbers could be higher than in USA because in the past years was reported that 10-40% of the newborn children have the infection and showed meningoencephalitis, hepatosplenomegaly, or hearth failure, rising the neonatal death risk5.

Due the lack of recognition of the importance of congenital Chagas disease infection in several non-endemic countries, this disease has become global due to population movements from endemic countries. Recently, there are reports of Chagas´ disease congenital transmission in non-endemic areas such as Japan6, Ireland7, and Spain8. In a meta-analysis, the risk of congenital transmission was calculated in approximately 3.5%9.

At present, congenital transmission represents the main route if the transmission in vector-free regions, moreover, this neglected tropical disease was approved at the World Health Organization global plan to interrupt four transmission routes by 2030 (vector, blood transfusion/organ transplant/congenital)4.

One interesting data regarding this issue is that in blood banks routine, T. cruzi infection testing is mandatory10 not so in pregnant women or in newborns11. It has been described that one of the factors that heavily influence the risk of vertical transmission is the parasite strain12. Thus, the goal of this study is to analyze the vertical transmission of a Mexican strain regards of its ability to be vertically transferred to the products in terms of patent parasitemia, antibodies, and tissular changes.

Materials and methods

Harem formation

BALB/c healthy mice 20 20 ± 2 g. (around 6 weeks old) was provided the physiology facilities (Animal House, Department of Physiology, Biological Sciences National School, National Polytechnic Institute). All animals were maintained and treated strictly according to the NOM-062-ZOO-199913, and all the procedures and experimental protocols were performed according to the Biological Sciences National School Bioethics Committee. Two harems, comprised six females and one male each (control and experimental groups), were established. From the moment of formation, vaginal introitus of the females was observed at 8-h intervals to ascertain the presence of the mating plug, thereby confirming successful copulation.

Mice and experimental groups

BALB/c healthy mice 20 20 ± 2 g. (around 6 weeks old) was provided the physiology facilities (Animal House, Department of Physiology, Biological Sciences National School, National Polytechnic Institute). All animals were maintained and treated strictly according to the NOM-062-ZOO-199913, and all the procedures and experimental protocols were performed according to the Biological Sciences National School Bioethics Committee. Two six female mice group were used, one was remains without pregnancy but intraperitoneally infected with 1 × 103 metacyclic trypomastigotes as control, and the second group with pregnancy (coming from the harem) was intraperitoneally infected with 1 × 103 metacyclic trypomastigotes. Parasitemia levels were determined in counting the parasite number in 5 μL of caudal vein mice blood using a Neubauer's chamber Brand' (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA)14.

Blood samples were taken, and then, pups were sacrificed at birth, at days 7, 14, 21, 28 (acute phase), and 90 (chronic phase) to obtained skeletal hind leg muscle and heart tissue, as these tissues were reported as the target tissues of this strain15.

Histopathological analysis

Heart and skeletal muscle tissue sections were fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 24 h, dehydrated in absolute ethanol (Merck Millipore, Rahway, New Jersey, USA), cleared in xylene (Merck Millipore, Rahway, New Jersey, USA), and embedded in paraffin (Merck Millipore, Rahway, New Jersey, USA). Five-micron tissue sections were mounted on glass slides IsoslideTM (Merck Millipore, Rahway, New Jersey, USA), deparaffinized, and processed using hematoxylin and eosin staining technique. We analyzed each tissue section for randomly selected, 10-microscopic fields (×100 magnification), and examined three different tissue sections/organs/animals. The tissue sections were evaluated microscopically by two individuals in a blinded manner, using an optical microscope NikonTM Eclipse 50i (Tokyo, Japan). The presence of inflammatory cells in H&E-stained sections was scored as 0 (absent), 1 (focal or mild, 0-1 foci), 2 (moderate, 2 foci), 3 (extensive inflammatory foci, minimal necrosis, and retention of tissue integrity), and 4 (diffused inflammation with severe tissue necrosis, interstitial edema, and loss of integrity).

Immunological analysis

Newborn sera were obtained 5 μL through a small cut of the caudal vein mice using a blood sampling device for newborn (Vygon, Écuen, France), and the microhematocrit capillary tubes (Kimble, Vineland, New Jersey, USA) were centrifugated at 3000 rpm/15 min. Sera were kept −4°C16.

T. CRUZI ANTIGEN

The antigenic extract was prepared with T. cruzi NINOA epimastigotes cultured in liver infusion tryptose, then the parasite was counted, using a Neubauer´s chamber. Then, epimastigotes were washed by triplicate using PBS 0.1 M pH 7.2. The total volume was sonicated 3 times of 18 kHz for 1 min, employing a sonicator SFX250 (Branson Ultrasonics, Brookfield, Connecticut, USA). Later, the volume was centrifugated 12,000 g 1 h at 4°C, the supernatant protein content was estimated by Lowry's method. Finally, the solution was kept at −20°C until use17.

ENZYME-LINKED IMMUNOSORBENT ASSAY (ELISA)

We performed a non-commercial indirect ELISA based on local antigens from T. cruzi NINOA strain that belongs to T. cruzi lineage I, predominating lineage in Mexico, because it has a slightly higher sensitivity compared to commercial serological test. Briefly, flat bottom microplates CostarTM (Corning, Corning, New York, USA) were coated with the T. cruzi antigen protein, at a concentration of 10 μg/mL in 0.1 M carbonate buffer pH 9.6. Then, unbound antigen was discarded with three washes of PBS 0.05% Tween, the plates were blocked to prevent false positive results with 200 μL of albumin (Hycel, Mexico), and incubated for 1 h at 37°C17.

Later, plates were incubated with 100 μL mouse sera at a final dilution of 1:500 (in duplicate). After being incubated overnight at 4°C, they were washed 3 times with PBS-0.05% Tween. After the washes, 50 μL of a peroxidase-coupled goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) at a dilution of 1:7500 in PBS Tween was added to each well and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. After carrying out three washes, 100 μL of a solution of ortho-phenylenediamine (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA), pH 7 carbonate buffer, distilled water, and hydrogen peroxide (Merck Millipore, Rahway, New Jersey, USA) were added after 3 min, the reaction was stopped with H2SO4 (Merck Millipore, Rahway, New Jersey, USA) and the plates were read at 490 nm in an ELISA HREADER1 reader (Hlab, Mexico).

Results

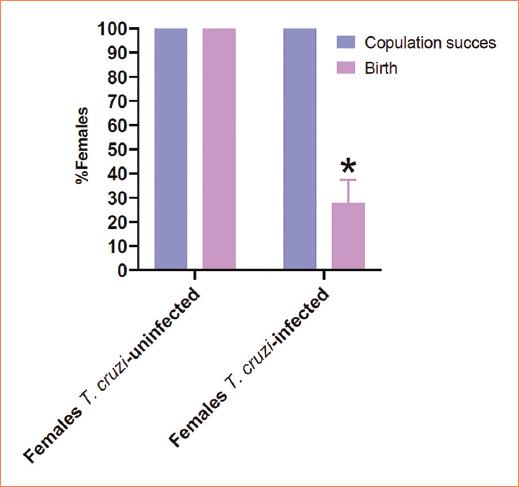

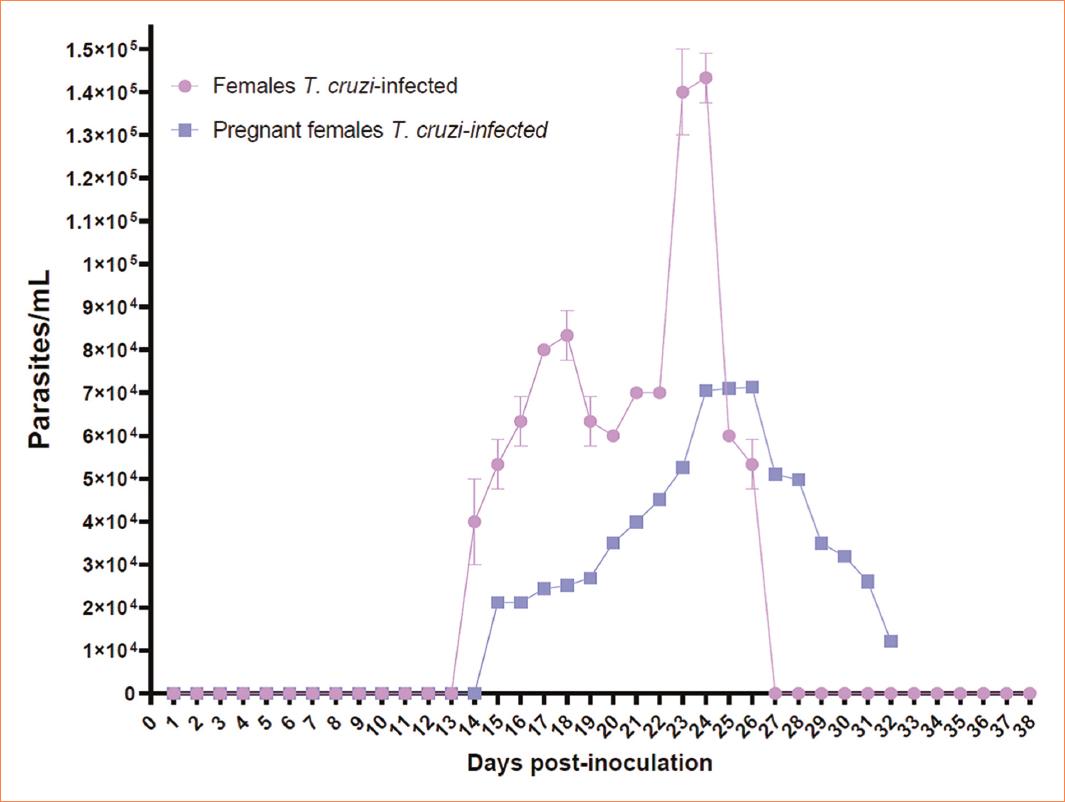

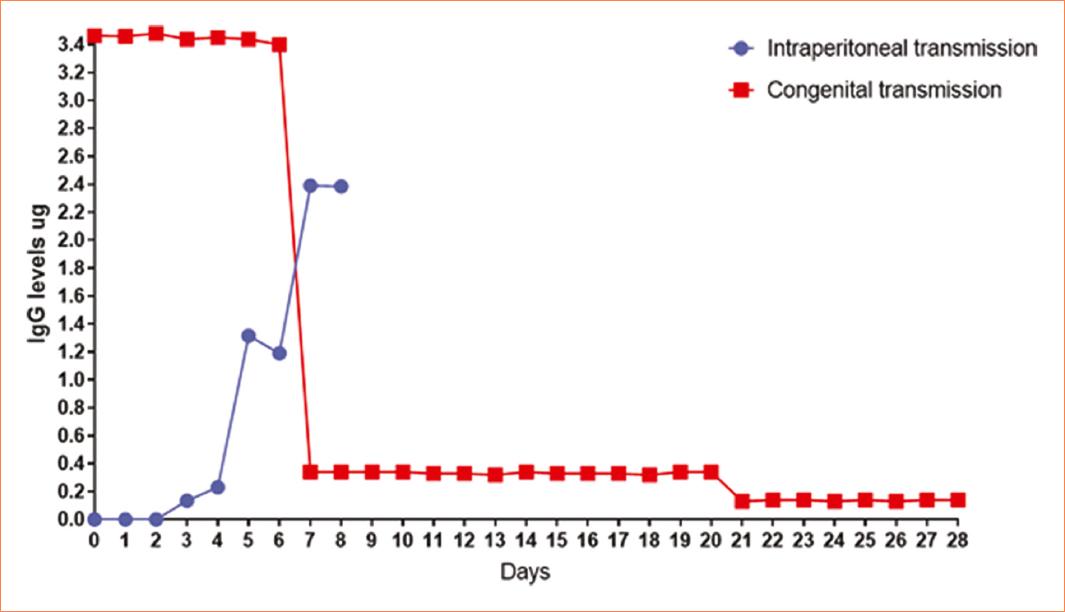

The observation of the mating plug determined copulation success, with both females T. cruzi infected and females T. cruzi uninfected exhibiting a 100% copulation success rate. However, despite achieving a 100% mating success in females, the percentage of births was < 30% in females infected with T. cruzi (Fig. 1) (p < 0.05). A parasitemia curve was conducted to compare the course of acute infection in the studied groups (Females T. cruzi infected, pregnant females T. cruzi infected). Over the observation days, three well-differentiated phenomena were evident. First, the onset of parasite presence in the bloodstream showed that in the non-pregnant group, parasitemia initiated earlier than in the pregnant female group (day 14 post-inoculation). In addition, a higher quantity of parasites in the blood (≈ 40,000) was observed in the non-pregnant group. The subsequent phenomenon was the peak of parasitemia, graphically evidenced by a higher number of parasites in the blood in non-pregnant females (day 23 post-inoculation), contrasting with pregnant females who exhibited a lower parasitic burden at this point. Pregnant females reached 100% mortality by day 32 post-inoculation, unlike non-pregnant females, who showed an end to parasitemia by day 27 post-inoculation (Fig. 2). The levels of serum antibodies against T. cruzi were assessed in newborn mice from infected mothers that gave birth and were compared with intraperitoneally inoculated newborns. The observed curve in neonates from infected mothers showed a high content of antibodies against T. cruzi from day 0, reaching a maximum value of 3.4 μg. In contrast, mice infected intraperitoneally did not exhibit serum concentration of these antibodies at the same time point. While neonates from infected mothers displayed a drastic decrease on day 7, mice infected intraperitoneally showed a gradual increase over the days, reaching their peak concentration on day 8; however, the entire group succumbed. Mice from infected mothers experienced another decrease in antibody concentration on day 20, remaining constant until the end of the assay with 100% survival (Fig. 3).

Figure 1 Copulation success. Mating plug (blue bar) was a 100% in all groups showing no statistical difference among groups, on the other hand, the birth (purple bar) was lower in Trypanosoma cruzi-infected females (p = 0.05).

Figure 2 Parasitemia curve. Non-pregnant females exhibited an onset of parasitemia on day 14 post-inoculation, with subsequent peak of parasitemia occurring on day 25, and parasitemia terminating on day 27. In pregnant females, onset of parasitemia occurred on day 15 post-inoculation, with peak of parasitemia observed on day 24. However, the end of parasitemia was not recorded because all pregnant females succumbed by day 32. Notably, non-pregnant females displayed higher parasitic density (p = 0.05) compared to the pregnant counterparts.

Figure 3 Immunoglobulinemia. The mouse pups infected intraperitoneally showed a gradual increase in antibodies against Trypanosoma cruzi. Reaching their maximum concentration on day 7 (2.4 μg), subsequently on day 8 these pups died due to the parasitic infection. Pups with congenital transmission showed the highest concentration of antibodies against T. cruzi from day 0 (3.4 μg), decreasing considerably on day 7 (0.4 μg), remaining constant for 13 days, a second decrease on day 21 (0.2 μg) remaining constant until day 28. Pups with congenital infection show a higher quantity of antibodies than those infected intraperitoneally (p = 0.05).

Discussion

T. cruzi involves a complex transmission, so it could serve as a unique model for the study of the adaptative parasite-host model12 because it seems to have a wide range of variations according to several factors, including the strain. T. cruzi strains present different capabilities to cause congenital infection, for example, no congenital murine infection was observed with T. cruzi K98 clone isolated from a congenital case VC/TcVI, this isolate has a higher survival rate in the placenta than Tulahuén strain in placenta4.

During pregnancy is necessary to have immune tolerance by the fact that the fetus express paternal antigens, that in other circumstances are recognized, and eliminated. Maternity immunity in the fetus-placental unity is deviated to an Th2 response to protect this process, explaining the presence of pregnancy-protecting cytokines as interleukin (IL)-10, transforming growth factor-b, and IL-4. These circumstances could alter the susceptibility of the host against protozoan infections, favoring congenital transmission18.

T. cruzi-infected pregnant women who transmitted the infection to their fetus blood cells have a functional deficiency in the IL-2 production and an unbalance in the production of IL-10 and interferon-gamma (IFNγ); T. cruzi-infected pregnant women who did not transmit the infection to their fetus blood cells have normal secretion of IFNγ and IL-218.

It has been reported that vertical transmission is more likely to happen when the parasitemia is higher in the mother19 related to the tissue infection, none of the pups has parasites in their heart or blood even when other TcI strains (AQ1-7) do have showed amastigotes in the tissues of the pups20, possibly because low infection that the pregnant females presented, but it could be the consequence of the immune response that happens during the pregnancy at placental level; briefly, it has been proposed that during congenital transmission blood trypomastigotes cross placental barrier, infects syncytiotrophoblast, cytrotrophoblast, and villious stroma, there the parasites differentiate into amastigotes, proliferate, and differentiates into trypomastigotes, and invade fetal capillary, and the fetus but this could be interrupted by the immune fetus defense21. It is important to take in count that each strain infects differentially the placenta, resulting of the virulence of each strain22, therefore is important to determine the strain that infects the pregnant female to help with an adequate management of each case.

Immunologically, fetus and neonates' congenital infection has interesting points: on one hand, their inflammatory cells could be activated by T. cruzi; on the other hand, the fact that they have maternal antibodies could help to contain and even eliminate the infection by opsonized the parasites, resulting in a brief congenital infection without the development of the disease23. This strong immune response could help to explain that 50% premature babies born of Chagas´ disease infected mothers do not survive21. Here, we do not detect parasites on pups blood smear by direct observation; however, IgG antibodies were detected, the antibody presence coincides with previously reported data in guinea pigs24, and supports the proposal that the pups do not develop the disease could be due the antibody-dependent enhancement mechanism, resulting into the activation of the phagocytic FcɣR pathway of the host cells25.

Given that there is no direct blood exchange between the fetus and the mother, high parasitemia would not be directly responsible for infection12. Previously, it has been correlated vertical transmission with a positive hemoculture, suggesting that to T. cruzi could be vertically transmitted is mandatory that the mother had elevated parasitemia26. In the present work, the parasitemia of the mothers lower during pregnancy contribute with evidence that mothers displayed an inflammatory response to control the infection to prevent the transmission, supporting that it has been reported higher levels of INF-γ27. Even more, there is a hypothesis that proposes that borne vector toward vertical infection should impart mother-to-child some protection against a challenge with more virulent strains28.

T. cruzi lineages discrete typing units (DTUS) seem to influence vertical transmission but there are not know the specific factors that contribute to it; moreover, it seems that every strain influences this transmission27. In one Brazilian and one St. Catherine's Island (USA) strain, was reported that the newborns died in approximately 2 weeks after birth, and the mothers died during the experiment12. In the present study, using NINOA stain, the newborns grow with no problems as it happened in a previous work performed with H4 strain in guinea pigs, both DTU I strains15,24. Then, the present assay shown and supports the idea that the DTUS have a big influence in the acute infection leading or not to the death of the hosts infected with T. cruzi.

Finally, we want to point out that acute T. cruzi-infected females were hard to get pregnant, data that support the proposal that T. cruzi appears to induce low reproductive rates in copulating female mice20. May be due the strong physiological inflammation status, moreover, in the present study, even when female mice got pregnant some of them present miscarriages maybe due the strong defense promote by the infection that implies the induction of inflammasome signaling in placental trophoblasts, the hyperactivation of blood cells and the releasing of proinflammatory cytokines such as IFN-ɣ that activates monocytes/macrophages and stimulates, in synergy with TNF-α the generation of NO to kill parasites23. Thus, we could suggest that the females that continue the pregnancy process displayed an inflammation status less aggressive than the ones that had miscarriages, supporting the previous data that in pregnant women, the predominant response is TH218.

In the present study, we performed our work employing NINOA strain and the parasitemia in the neonates remained subpatent parasitocopically, data that coincide with the information about other TcI T. cruzi strains (X10)20,29. However, further studies related to the factors that influence parasite´s multiplication during pregnancy is needed.

Conclusion

In one hand, T. cruzi strain and parasitemia load of the pregnancy female are two important factors to take in account to dilucidated the possibility of a vertical transmission; it seems that every strain behaves differently. On the other hand, the pregnancy itself acts as a protective factor against the newborn possible infection due the T. cruzi-antibody production.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)