INTRODUCTION

Coral reef ecosystems and their complex ecological interactions are home to a great diversity of marine species, including fishes. The relationship between reef fishes and coral cover has been widely documented (Muruga et al. 2024), highlighting the importance of coral colonies as refuge areas that facilitate the convergence of diverse ecological processes (Komyakova et al. 2013). These processes and interactions, along with the use and distribution of resources, play a key role in structuring benthic communities. Worldwide, studies have identified more than 320 fish species that use live corals as their main habitat and refuge, representing approximately 8% of the total diversity of reef fishes (Coker et al. 2014). These interactions could be related to refuge search or establishment (i.e., Cirrhitidae), feeding (i.e., Stegastes), and predation (i.e., Scaridae), among other ecological processes (Depczynski and Bellwood 2003). However, a large number of reef fish species are not obligately dependent on live corals and make extensive use of the ecosystem, influencing reef trophodynamics (Depczynski and Bellwood 2003, Coker et al. 2014).

Most studies on fish-coral associations have focused on regions of high diversity and large areas of coral cover, such as the Caribbean (Olán-González et al. 2020) or the Indo-Pacific (Holbrook et al. 2008, Coker et al. 2014, Moynihan et al. 2022). In both regions, fish diversity increases with coral presence and cover (Coker et al. 2014). In that respect, several studies have evaluated the influence of benthic characteristics on the structuring of fish fauna in the Eastern Tropical Pacific (ETP) (Dominici-Arosemena and Wolff 2006, Galván-Villa et al. 2011, Ricart et al. 2016, Salas-Moya et al. 2021); however, the effect of habitat on the ichthyofauna in the ETP is not entirely clear, with some authors suggesting that fish diversity increases with greater habitat complexity (Benfield et al. 2008), whereas others indicate that fish diversity decreases as coral cover increases (Olán-González et al. 2020). In addition, ETP reefs are considered isolated coral patches, called rocky-coral fringing reefs, mainly due to the narrow continental shelf that prevents the development of large reef areas (Reyes-Bonilla 2003), since the majority of the coral reef-forming species (i.e., Pocillopora) do not develop beyond 8-m depths (López-Pérez et al. 2024).

There is a group of reef fishes called cryptobenthic reef fishes (CRF), which are small fishes with total lengths that do not exceed 5 cm in their adult stage (Depczynski and Bellwood 2003, Brandl et al. 2018). CRF show limited dispersal, low longevity, quick generational turnover, and high specialization in their habitat preferences (Hastings and Galland 2010, Brandl et al. 2018). Furthermore, on tropical reefs, CRF can represent more than 40% of the diversity of fish species (Ackerman and Bellwood 2000) and up to 85% of the total abundance (Galland et al. 2017). However, evaluating CRF assemblages is not easy because they are difficult to obtain, show extremely miniaturized anatomical structures that complicate their identification, and vary greatly in color in different growth stages (Brandl et al. 2018). Thus, CRF are highly dependent on the availability of specific microhabitats due to their specialized habitat preferences. Microhabitats are small areas within a larger habitat that are differentiated from the surrounding environment by structural, faunal, ecological, or climatic characteristics (Morrison et al. 2012, Shi et al. 2016). Therefore, when studying CRF, microhabitats are usually classified based on the characteristics of benthic structures (i.e., cracks, coral debris, or boulders) or the type of coral morphology (Depczynski and Bellwood 2004, Brooks et al. 2007, Troyer et al. 2018).

In the north-central region of the Gulf of California, rocky reefs are mainly made up of the species Porites panamensis that forms colonies and isolated patches (Reyes-Bonilla and López-Pérez 2009), with average percentage of cover values of around 1% (Glynn et al. 2017), although in some regions of the Gulf of California, such as Bahía de los Ángeles, this value increases until reaching 3.5% (Norzagaray‐López et al. 2015). This coral species could be key in the creation of coral microhabitats, contributing notably to the biodiversity of the Gulf of California, an ecosystem that hosts approximately 4,852 species of invertebrates and 911 species of fish (Brusca 2010), and 16-20 species of scleractinian corals, with the genera Pocillopora and Porites being the most abundant (Reyes-Bonilla et al. 2005, Glynn et al. 2017). Therefore, studying fish associated with coral microhabitats is essential to understand their ecological role.

In recent years, the use of 3D modeling and photogrammetry tools has revolutionized the study of coral structures. These technologies allow us to obtain precise data on the three-dimensionality and complexity of seabed structures, which has transformed coral reef research (Storlazzi et al. 2016, Urbina‐Barreto et al. 2022). In addition, they allow us to overcome the small-scale limitations of traditional methods by enabling 3D reconstructions of individual coral colonies and microhabitats (Urbina-Barreto et al. 2021), which facilitates the study of associated cryptofauna (Curtis et al. 2023). Considering this, we used 3D modeling tools to evaluate the complexity and importance of the massive coral P. panamensis and its influence on the structuring of CRF. To do this, fish were collected in microhabitats made up of coral and rock to later evaluate their association with these structures. Therefore, the objective of this study was to compare the density, structure, and composition of the CRF community between coral microhabitats, made up of the P. panamensis, and rocky microhabitats. We hypothesize that CRF richness and density will be greater in coral microhabitats because these microhabitats are three-dimensionally more complex. This study provides empirical evidence to better understand the association of CRF with the microhabitats in the Gulf of California.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area

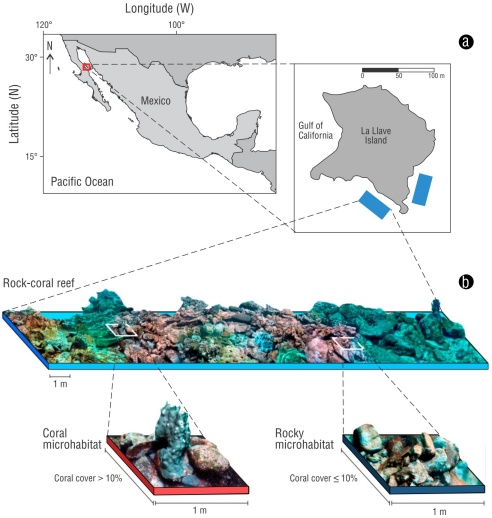

The study was carried out on a shallow rocky-coral reef located in the southern part of La Llave Island (Fig. 1a). This island is located within Bahía de los Ángeles, Zona marina Bahía de los Ángeles, canales de Ballenas y de Salsipuedes Biosphere Reserve, in the north-central region of the Gulf of California. This region is characterized by an arid climate and high seasonal climate variability. Between February and April, sea surface temperatures can drop to less than 16 °C; in the months of August and September, they can exceed 27 °C (Martínez-Fuentes et al. 2022).

Figure 1 Study area. The blue polygons indicate the areas where sampling was carried out on La Llave Island, Zona marina Bahía de los Ángeles, canales de Ballenas y de Salsipuedes Biosphere Reserve (a). Schematic drawing of a rocky-coral reef composed of coral microhabitats (Porites panamensis) and rocky microhabitats (b).

Field work

To compare CRF assemblages in coral and rock microhabitats, 2 field trips were carried out, the first in March 2022 and the second in October 2022. We obtained 8 sample units in each season (Table S1). We defined coral microhabitats as 1-m wide by 1-m long areas, with a percentage of P. panamensis coral cover greater than 10% (Fig. 1b). Conversely, rocky microhabitats were classified as those areas with coral cover equal to or less than 10%, and a predominance of rock. It should be noted that P. panamensis is the only species of scleractinian coral observed in the study area.

We analyzed 16 microhabitats at average depths of ~5.7 m with scuba diving equipment: 5 coral microhabitats and 11 rocky microhabitats (Table S1). First, a 12-cm diameter metric reference was placed and 1-min recordings were made using a circular scan to capture the three-dimensional structure of each microhabitat. Recordings were made with a GoPro Hero 10 camera (GoPro, San Mateo, USA) set at a resolution of 2,704 × 1,520 pixels (2K) and a speed of 60 photographs per second. Subsequently, fish were extracted from each microhabitat using a conical net with an opening area of 0.42 m2 and mesh size of 0.5 mm (Fig. S1) and a solution composed of 100 mL of concentrated clove oil (eugenol) and 900 mL of 96% ethanol as an anesthetic (Depczynski and Bellwood 2004). We waited ~1 min for the anesthetic to take effect and collected all the fish inside the net. In the laboratory, each individual was identified to the species level based on Ginsburg (1938), Rosenblatt and Taylor (1971), Bussing (1990), and Robertson et al. (2024). To prepare the final list, the name of each species was corroborated and validated using the Eschmeyer catalog (Fricke et al. 2023).

Image processing

To generate 3D models of the microhabitats in the Agisoft Metashape software (Agisoft LLC, Saint Petersburg, Russia), frames were extracted from each microhabitat video following the methodologies of Burns et al. (2015) and Fukunaga et al. (2019). Coral cover was estimated with the 3D model orthomosaics using the Coral Point Count with Excel extensions software (Kohler and Gill 2006) by overlaying 30 random points in each microhabitat (Tabugo et al. 2016). The 3D rugosity was estimated from the 3D models using the methodology of Ventura et al. (2020), with the following formula:

where R 3D is the 3D rugosity as a proxy for habitat complexity, SA 3D is the three-dimensional area of the microhabitat model, and A 2D is the planar area or base area occupied by the microhabitat model.

Data analysis

To compare 3D rugosity and CRF richness and density between coral and rock microhabitats, we performed a Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon analysis with the ‘stats’ package. On the other hand, to compare the composition and structure of CRF assemblages between microhabitats, we performed a one-way permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) using a Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrix based on the transformed CRF density data (

Finally, we evaluated the preference of species for coral and rocky microhabitats with a similarity percentage analysis (SIMPER) and made an alluvial diagram to graphically illustrate it. The SIMPER analysis allows us to discriminate between 2 groups of species based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarities and provides the average contribution per species (Oksanen et al. 2019):

where δ

jk

i is the dissimilarity associated with the ith species between samples j and k. We obtained the average contribution per species (

RESULTS

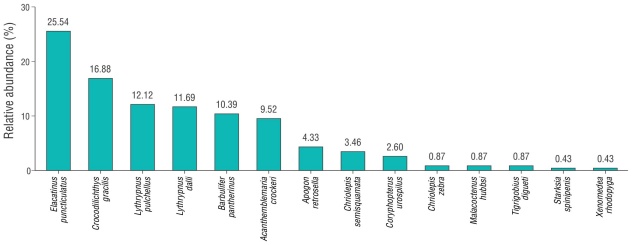

We collected 238 CRF from 14 species. However, 5 species represented 76.62%: Elacatinus puncticulatus, Crocodilichthys gracilis, Lythrypnus pulchellus, Lythrypnus dalli, and Barbulifer pantherinus (Fig. 2). Average CRF richness was slightly higher in coral microhabitats than in rocky microhabitats, with values of 5.6 ± 1.3 (

Figura 3 Comparison of richness (a) and density (b) of cryptobenthic reef fish (CRF) in coral microhabitats (Porites panamensis) and rocky microhabitats. Assemblage composition analysis using non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) of the density of the 14 CRF species in the 16 analyzed microhabitats (c). The results of the Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon analyses and permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) are shown at the top of the graph.

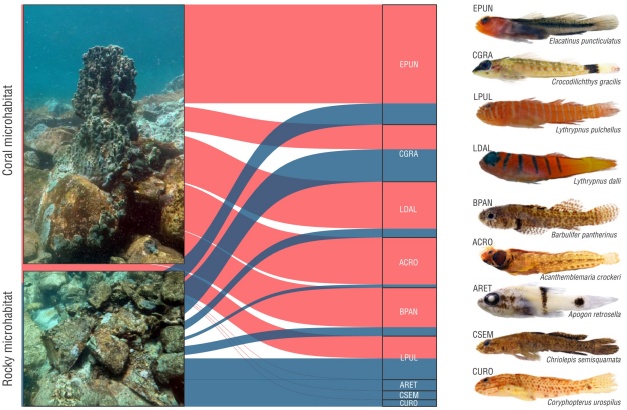

The PERMANOVA analysis showed significant differences in the structure and composition of CRF assemblages between coral and rock microhabitats (Pseudo-F = 4.4, P = 0.004). Similarly, the NMDS revealed a differential ordering of 2 clearly defined groups, graphically evidencing the dissimilarity in the structure and composition of CRF assemblages for each microhabitat (Fig. 3c). The SIMPER analysis allowed us to identify the CRF species that contributed the most to this dissimilarity between microhabitats (Table 1). The species E. puncticulatus, Acanthemblemaria crockeri, and L. dalli contributed the most to the differences between microhabitats. Concurrently, these species had the highest density values in coral microhabitats, whereas other species, such as C. gracilis, Apogon retrosella, Chriolepis semisquamata, and Coryphopterus urospilus, had highest values in rocky microhabitats (Table 1, Table S2). In addition, the alluvial diagram allowed us to graphically represent the typical structure of CRF assemblages in coral and rocky microhabitats (Fig. 4). Regarding habitat complexity, 3D rugosity reached an average value of 2.03 ± 0.56 in coral microhabitats, whereas rugosity was 1.69 ± 0.40 in rocky microhabitats. Nevertheless, differences between microhabitats were not significant (Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon, W = 38, P = 0.257).

Table 1 Average density and similarity percentage analysis (SIMPER) of all cryptobenthic reef fish (CRF) species collected in coral microhabitats (Porites panamensis) and rocky microhabitats. *Endemic species of the Cortez biogeographic province (Palacios-Salgado et al. 2012).

| Species | Average density (ind·m-2) | |||

| Average contribution (%) | P value | Coral

( |

Rocky

( |

|

| Elacatinus puncticulatus | 19.05 ± 7.26 | 4.11 ± 1.25 | 17.66 | 0.020 |

| Acanthemblemaria crockeri* | 9.05 ± 1.75 | 0.65 ± 0.46 | 12.21 | 0.001 |

| Lythrypnus dalli | 9.05 ± 4.15 | 1.73 ± 0.79 | 10.70 | 0.008 |

| Barbulifer pantherinus* | 7.62 ± 3.48 | 1.73 ± 0.56 | 7.37 | 0.094 |

| Crocodilichthys gracilis* | 4.76 ± 1.99 | 6.28 ± 1.99 | 7.27 | 0.995 |

| Lythrypnus pulchellus | 4.29 ± 2.65 | 4.11 ± 2.73 | 6.80 | 0.967 |

| Apogon retrosella | 2.16 ± 0.50 | 3.11 | 0.713 | |

| Chriolepis semisquamata* | 1.73 ± 0.85 | 2.35 | 0.991 | |

| Coryphopterus urospilus | 1.30 ± 0.67 | 2.21 | 0.981 | |

| Tigrigobius digueti | 0.95 ± 0.95 | 0.76 | 0.023 | |

| Chriolepis zebra* | 0.43 ± 0.29 | 0.63 | 0.981 | |

| Malacoctenus hubbsi* | 0.43 ± 0.43 | 0.54 | 0.987 | |

| Starksia spinipenis | 0.48 ± 0.48 | 0.47 | 0.021 | |

| Xenomedea rhodopyga* | 0.48 ± 0.48 | 0.47 | 0.021 | |

Figure 4 Alluvial diagram of the preference of the most abundant cryptobenthic reef fish species and their affinities towards coral and rocky microhabitats. EPUN = Elacatinus puncticulatus, CURO = Coryphopterus urospilus, CGRA = Crocodilichthys gracilis, LPUL = Lythrypnus pulchellus, LDAL = Lythrypnus dalli, BPAN = Barbulifer pantherinus, ACRO = Acanthemblemaria crockeri, ARET = Apogon retrosella, CSEM = Chriolepis semisquamata. The thickness of the lines is proportional to the average density of each species in each microhabitat.

DISCUSSION

In the Mexican Pacific, numerous studies have explored the influence of habitat complexity on the structuring of fish assemblages (i.e., Aburto-Oropeza and Balart 2001, López-Pérez et al. 2013). However, these studies have commonly involved conspicuous species and evaluated relatively general characteristics of the reefs, such as coral cover, bottom rugosity, or variables derived from functional diversity analyses (Olán-González et al. 2020, Dubuc et al. 2023). Few studies in the TEP have analyzed, at a very fine spatial scale (i.e., 1 × 1 m), the influence of microhabitats (i.e., soft corals, hard corals, rock, and rubble) on the structure of cryptic fish assemblages (Alzate et al. 2014, Galland et al. 2017, González-Murcia et al. 2023). This study analyzes the importance of the coral P. panamensis in structuring the CRF of the north-central Gulf of California. The results of this study offer a window to explore the importance of this under-evaluated group of fish and how they could be influenced by microhabitat characteristics, particularly in reef-building corals.

Corals of the genus Porites can develop highly complex habitats, measuring more than 6 m in diameter and housing a notable abundance and diversity of reef fishes (Nanami and Nishihira 2004). Porites colonies with branching columnar morphology have been documented to host even greater functional richness of fish compared to corals of the genus Pocillopora (Richardson et al. 2017). The present study showed no differences in CRF richness between rocky and coral microhabitats, which differs from what was reported in the Pacific of Panama by Dominici-Arosemena and Wolff (2006), who observed differences in fish diversity between microhabitats of massive corals, branching corals, and coral rubble. However, in this study, we probably did not observe significant differences between microhabitats due to the low number of species recorded. Rocky microhabitats had a cumulative specific richness of 11 species, and coral microhabitats had a cumulative richness of 9 species (Table 1). Specific richness depends on sampling effort (Magurran 2003); therefore, long-term spatiotemporal studies will significantly improve the quality of the biological inventory of both microhabitats.

On the other hand, in this study, the average density of CRF in rocky microhabitats was 24.68 ± 4.06 ind·m-2, which was very similar to the 20.9 ± 1.7 ind·m-2 reported by González-Cabello and Bellwood (2009) in Loreto Bay, Gulf of California. Contrary to our results, these authors observed relatively low densities in coral colonies, where Protemblemaria bicirris (20.66%) and A. crockeri (14.37%) were the dominant species. On the other hand, in this study, we observed that coral microhabitats (9.05 ± 1.75 ind·m-2) had higher densities of A. crockeri than rocky microhabitats (0.65 ± 0.46 ind·m-2), whereas González-Cabello and Bellwood (2009) observed an opposite pattern for this species, which was more abundant in rock (5.00 ± 1.24 ind·m-2) than in coral heads (Pocillopora) (1.50 ± 0.85 ind·m-2). This suggests that local factors, along with habitat availability and structure, influence both the distribution and habitat preferences of species (Arias-González et al. 2006). Therefore, our hypothesis was partially confirmed. Despite the higher density values recorded in coral microhabitats, these did not correspond to an increase in richness. We expected that habitat complexity would be a determining factor under the premise that corals would have greater structural complexity. However, the analyses showed no significant differences in 3D rugosity, which suggests that corals were not structurally more complex than rocky microhabitats.

It is important to note that only P. panamensis has been detected as an important species in the construction of shallow coral reefs in Bahía de los Ángeles, whereas further south (i.e., Loreto), it has been reported that other species of hard corals that form coral reefs are more important in terms of coral cover (i.e., Pocillopora). Therefore, the results of González-Cabello and Bellwood (2009) and those of this study could indicate that there are CRF assemblages for each coral species. Troyer et al. (2018) determined that there is a CRF structure for each type of substrate in shallow reefs of the Red Sea, where the abundance, diversity, and richness of species was greater in rubble microhabitats than in coral reefs or sandy substrates; however, at the species assemblage level, they identified particular species for each type of microhabitat. In fact, Brandl et al. (2018) and Brandl et al. (2020) have described unique assemblages for each type of substrate or microhabitat and have determined that, in addition to a marked differentiation in assemblages of species, there is a marked intra- or interspecific partitioning of the trophic niche.

In the northern Gulf of California, P. panamensis likely plays a crucial functional role as a microhabitat for CRF, similar to what has been observed for cryptobenthic species in other regions of the world (Brandl et al. 2018, Troyer et al. 2018). The importance of CRF in reef trophodynamics was not evaluated in this work; however, CRF are known to contribute substantially to the recycling of matter and energy in the Gulf of California. Galland et al. (2017) demonstrated that, in the Gulf of California, CRF represent more than 40% on average of the species richness per site, more than 95% of the total fish abundance, and up to 56% of the metabolic requirements on a reef. These authors divided the Gulf of California into north and south (Bahía de los Ángeles is in the north of this division), and reported that there is a greater contribution of CRF in biomass, abundance, and metabolism in the north. Therefore, the authors suggest that CRF are a crucial group of fish in the recycling of matter and energy, although this contribution seems to have greater relevance in the islands of the northern Gulf of California than in the south. Furthermore, Ackerman and Bellwood (2000) obtained similar results on Orfeo Island, Australia; these authors determined that fish less than 10 cm in length can use more than 57% of the metabolism of the ecosystem. Brandl et al. (2018) also demonstrated that CRF have much higher metabolic rates, mortality rates, and fecundity than conspicuous fish, and concluded that, as a biological group, CRF have very high turnovers in the ecosystem, categorizing CRF as the “pivotal” part of the reefs.

CONCLUSIONS

The Gulf of California is among the most diverse and productive ecosystems in the world, where 104 species are CRF (40% are endemic to the Gulf of California; Galland 2013). Because CRF have no commercial value for human consumption, they have generally been excluded from ichthyological evaluations in the Mexican Pacific. However, they play crucial roles within ecosystems by having close associations with the benthos, providing vital energetic links between the benthos and nekton and playing an important role in the trophodynamics of coral reefs by providing energy towards larger consumers (Galland et al. 2017). In the present study, the structure and composition of CRF assemblages differed between rocky and coral microhabitats, with higher CRF density in coral microhabitats. Furthermore, 5 species contributed 76.62% of the total abundance. This work represents one of the first efforts to understand the structuring of CRF in the shallow reefs of the Mexican Pacific. Future efforts should focus on understanding the role of CRF in reef trophodynamics in the region and sites further south, especially as the coral recovery and restoration programs proposed in recent decades in the central-southern Mexican Pacific have not evaluated CRF, despite the crucial role they likely play in these processes. Furthermore, the low environmental tolerance, rapid population turnover times, and scarce exploitation of CRF (Brandl et al. 2018) make them a model group to generate ecological hypotheses in ichthyological studies in the Mexican Pacific.

texto en

texto en