INTRODUCTION

Childhood obesity is considered a risk factor for chronic diseases (WHO, 2022), low quality of life and psychological problems (Rankin et al., 2016; Trujano-Ruiz et al., 2013). Data from the World Health Organization (WHO) indicate that at an international level, the prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents aged five to nineteen increased from 4% in 1975 to over 18% in 2016 (WHO, 1994; WHO, 2022).

In Mexico, overweight and obesity in pupils aged five to eleven is a priority issue due to the increase in prevalence. The National Health and Nutrition Surveys (Spanish acronym ENSANUT) show that the population reported a combined prevalence of overweight and obesity in this age range of 26% in 2006, 35.6% in 2018, and 38.2% in 2020 (Gutiérrez et al., 2012; Olaíz-Fernández et al., 2006; Shamah-Levy et al., 2020). For the above reasons, it has become essential to identify the correlations and predictors of the alarming increase in these indicators to reduce rates.

While genetics plays a critical role, other physiological, social, behavioral, and psychological factors also have a substantial impact. Children with overweight or obesity are more likely to have psychosocial problems than their peers with a healthy weight, in addition to suffering from the stigma attached to obesity, criticism and bullying, with the resulting health consequences, although it is unclear whether psychological and psychiatric problems are a cause or consequence of childhood obesity (Rankin et al., 2016).

Regarding eating psychopathology, international literature shows that between 7% and 17% of children aged seven to twelve present with disordered eating behaviors (DEB) and that prevalence is higher among those suffering from obesity (Gowey et al., 2014). In Mexico, the ENSANUT found that in both boys and girls between the ages of ten and thirteen, concern about weight gain was more frequent, with 11.4% and 11.3%, followed by overeating with 10% and 9.9%, and loss of control over eating, with 7% and 5.8% respectively (Olaíz-Fernández et al., 2006).

Franco-Paredes et al. (2017) found that in children aged ten and eleven with overweight and obesity in Mexico, DEBs occurred in 22.9% and 15.9% respectively, coinciding with the data reported internationally (Caleyachetty et al., 2018).

Eating psychopathology includes Binge Eating Disorder (BED), characterized by recurrent episodes of overeating while experiencing a feeling of loss of control over what or how much one is eating, accompanied by great distress, without involving any compensatory behavior and with possible weight gain as a result. Apropos of this, the first meta-analytical review of children and adolescents aged five to twenty-one with overweight and obesity was recently published. The results showed that binge eating and loss of control over eating occurred in a quarter of children regardless of race, sex, age, body mass index or evaluation method (He et al., 2017).

Regarding the research methods used to diagnose DEBs and BED in children, structured and unstructured interviews such as the Kids’ Eating Disorder Survey (KEDS) and the Eating Symptom Inventory (ESI) have predominated. None of them, however, evaluates loss of control, a crucial element in diagnosis (Childress et al., 1993; Whitaker et al., 1989). The Children’s Eating Disorders Examination (ChEDE) and the adolescent version of the Questionnaire on Eating and Weight Patterns (QEWP-A) have also been used. However, both showed discrepancies when assessing binge eating or loss of control over eating (Morgan et al., 2002; Tanofsky-Kraff et al., 2004). Evaluating EDs in children requires readily available, age-appropriate interviews, given that the diagnostic criteria developed for adults may not be appropriate, and that children find it difficult to answer recall questions, or engage in lengthy interviews with open-ended questions, which does not mean that BED does not occur in children, but rather that a specific age-appropriate approach is required. This led Marcus and Kalarchian (2003) to propose provisional criteria for measuring BED in children, based on a review and summary of findings from studies focusing on the age of onset of binge eating. The only specific questionnaire for children validated in Mexico is ChEAT (Escoto & Camacho, 2008), with a reliability of .82.

As a result, Shapiro et al. (2007) developed the Children’s Binge Eating Disorder Scale (C-BEDS), administered to the US child population with a mean age of 8.7 within a range of five to thirteen years regardless of body weight. Subjects were Caucasian (58%), African American (30.9%), Asian (1.8%), Native American (1.8%), or Hispanic (1%) or self-identified as “other” (5.5%). The scale comprises simple, understandable, quick, and appropriate questions to capture the key characteristics of BED (Shapiro et al., 2007). The scale contains seven items based on the critical behaviors proposed by Marcus and Kalarchian. Six of the items are binary, while item six measures the duration of the behaviors in weeks. The results showed that approximately half the children reported sometimes eating without being hungry, not being able to stop once they had started to eat and wanting food as a reward for doing something well.

Finally, 63% of the subjects stated that they ate because of negative emotions, while 29% of the total sample met the BED provisional criteria. The C-BEDS therefore proved to be a viable alternative and easier to administer to children to identify binge eating behaviors (Shapiro et al., 2007).

The usefulness of the C-BEDS was compared with that of the ChEAT in a sample aged six to twelve. It proved more effective in identifying eating behavior due to negative emotions and the possibility of developing BED (Dmitrzak-Węglarz et al., 2019). The scale has been administered in other contexts.

In Poland, Dmitrzak-Węglarz et al. (2019) examined 550 healthy children within an age range of six to twelve years, to determine whether a correlation exists between overweight and obesity and BED symptoms and to verify the usefulness of the scale as a BED screening instrument. The C-BEDS scale was also used as the basis for developing the Children’s Brief Binge-Eating Questionnaire. Franklin et al. (2019) developed the questionnaire and administered it to seventy children aged between seven and eighteen who were patients at an obesity clinic in the Southeast of the United States.

The objective of the present research was to evaluate the psychometric characteristics of the C-BEDS in a child population from fourth to sixth grade at public schools in the states of Campeche (southeast Mexico) and Mexico (central Mexico). A self-administered version was used to avoid the difficulty of undertaking individual diagnostic interviews and to determine the usefulness of this instrument for large-scale surveys. The reliability of the scale and exploratory and confirmatory validity were obtained in two samples of Mexican children. In addition, the percentage distribution of each of the items in the questionnaire was reported by sex.

METHOD

Sample

All the children included in the purposive sampling study in the morning shift at four schools in the federal school system of the Ministry of Public Education: two in the State of Campeche and two in the State of Mexico. The sample comprised 386 children, eight of whom did not wish to participate, leaving a total of 378, including 193 girls (51.1%), and 185 boys (48.9%), who were elementary school pupils in the states of Campeche (n = 249; 51% girls) and Mexico (n = 129; 51.2% girls) in the period from May to July 2022. The t test yielded a mean age of 10.22 (SD = 0.94) (t = 1.26, p = .206), with no statistical differences by sex, and an age range of eight to twelve.

Instruments

C-BEDS is a brief interview designed to assess the risk of binge eating in children. It comprises seven items based on the characteristic behaviors proposed by Marcus and Kalarchian (2003), six of which are binary questions and one of which measures the evolution of behaviors. Questions are scored 0 (no) and 1 (Yes). Children are classified as being at risk of BED if they answer “yes” to the questions on eating without being hungry and feeling unable to stop eating, and at least one of the questions about eating in response to emotions, eating as a reward or hiding food, having symptoms that have persisted for more than three months (question six), and question seven “Do you ever do anything to get rid of what you ate?” (Shapiro et al., 2007).

Shapiro et al. (2007) found that the question on the duration of the evolution of symptoms was unreliable because children lack a clear notion of time beyond three months in the past. For this reason, we deleted question six in the reliability and validity analysis of the scale, and performed the analysis with the six items scored with yes (1) and no (0). We called this version of the questionnaire the Self-Administered Children’s Binge Eating Disorder Scale (SA-C-BEDS).

To obtain the definitive version, the scale was translated using the back translation method from English to Spanish. A translator whose mother tongue is Spanish translated the scale from English to Spanish, and a translator whose mother tongue is English subsequently translated it from Spanish to English to ensure that the items maintained the same meaning as in the original scale (van Widenfelt et al., 2005). This seven-item version was used to conduct cognitive laboratories with fifteen children from fourth to sixth grade of elementary school in the State of Morelos, Mexico. They were asked about their understanding of both the questions and the structure of the questionnaire. Three of the authors of this article (CU, IC, LAR) participated in writing the final items according to the results of the cognitive laboratories. The version resulting from this phase was administered to children within this age range to check their understanding of the concepts and answer form. The definitive version was made up of all the items from the original version, which were uploaded to an online platform together with a battery of questionnaires, two of which were developed and validated in Mexico in samples of adolescents and adults: disordered eating behaviors (Unikel et al., 2004) and thin ideal internalization (Unikel et al., 2006), while three were developed in other countries: body dissatisfaction (Stice et al., 2006), appearance-related teasing (Castillo et al., 2023) and negative affect (Robles & Páez 2003).

Procedure

Contact was established with the school authorities in the area, who, after agreeing to participate in the study, liaised between school principals and researchers. The questionnaires were administered by sending internet links via WhatsApp, initially to the school principals, and subsequently to the teachers of elementary school pupils from fourth to sixth grade in the four participating schools. Teachers sent the internet link to parents, explaining that before answering the questions, they should read the informed consent form and decide whether they wished their children to participate. If they chose not to, that would indicate the end of their participation. Given that the children were asked to provide their informed consent, parents were asked to help them if they had problems understanding and answering the consent form, although only the children answered the questionnaires.

Data analysis

Analyses of frequencies and percentages were conducted with central tendency measures of the demographic variables and for each of the questions on the scale. Item-total correlations were obtained, considering that items with a value of less than .20 should be eliminated (Streiner & Norman, 2008). An exploratory factor analysis was conducted (Field, 2009), based on Yela’s criteria (1997) according to which 1) An item must have a saturation equal to or greater than .40, 2) An item is only included in the factor with the highest level of saturation, 3) Conceptual congruence must exist between all the items included in a factor, 4) To be considered as such, each factor must comprise at least three items. Finally, a confirmatory factor analysis was conducted (Brown, 2015). The sample was randomly divided into two parts, yielding an initial sample of 197 subjects (ninety-six girls and 101 boys) and a second sample with 181 subjects (ninety-seven girls and eighty-four boys), so that the exploratory analysis could be undertaken with one and the confirmatory analysis with the other, and in both cases, the quota of five to twenty participants per item was achieved (Campo-Arias & Oviedo, 2008; Sánchez & Echeverry, 2004). In addition, the statistical power of the sample was obtained for a medium effect size of .922 and .896 respectively (Cárdenas & Arancibia, 2016) and the minimum requirement of 150 subjects was met to conduct the confirmatory factor analysis (Wang & Wang, 2012), reliability was obtained with Ordinal alpha (Meulman et al., 2004). SPSS 21.0 (IBM Corp, 2012), JASP (JASP Team, 2020), Factor (Lorenzo-Seva & Ferrando, 2011) and G *Power (Faul et al., 2007) were used for the data analysis.

RESULTS

Disordered Eating behaviors

Disordered eating behaviors are shown separately for boys and girls. The main behavior found was eating without being hungry, with 44.8% in girls and 33.7% in boys, followed by eating when they are in a bad, sad, bored or other mood, with 25.0% in girls and 21.8% in boys, followed by eating as a reward for doing something, with 26.0% in girls and 23.8% in boys, followed by being unable to stop eating, with 15.6% and 15.8% respectively, and hiding food, with 18.8% and 12.9% respectively. No statistically significant differences were found by sex.

Reliability and exploratory validity

The item-total correlations were obtained, considering the full original scale. The first five questions showed values greater than .20, while questions six and seven obtained values of .10 and .14, respectively. According to Streiner & Norman (2008), item-total correlations of at least .20 are required to retain an item so we considered removing these two items. Notwithstanding the above, due to the conceptual importance of items six and seven, however, we conducted the factor analysis with the seven items comprising the scale. The analysis yielded a two-factor structure, the first comprising questions one to five, and the second questions six and seven. Since it is important for the factor to contain at least three items (Yela, 1997), in addition to the fact that questions six and seven have item-total correlations of less than .20 and since item six was considered inappropriate for children because of the difficulty of recalling the length of time they have engaged in these behaviors (Shapiro et al., 2007), we decided to eliminate these questions and repeat the factor analysis with questions one to five.

As a result, only one factor was obtained, (Table 1), with a significant Bartlett sphericity test (B = 104.77, df = 15; p < .001) and a Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test value of .73 (KMO). Ordinal alpha reliability was calculated, yielding a value of .81. The last version of the scale is a modified version with five items.

Table 1 Factor loadings for the exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis of the Self-administered Children's Binge Eating Disorder Scale

| Item |

Factor

Loadings |

|

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Do you ever want to eat when you are not even hungry? ¿A veces quieres comer cuando no tienes hambre? |

.671 |

| 2 | Do you ever feel that when you start eating you just cannot stop? ¿A veces sientes que cuando empiezas a comer, no puedes parar? |

.675 |

| 3 | Do you ever eat because you are in a bad, sad, bored, or any other mood? ¿A veces comes porque te sientes mal, triste, aburrido o de cual- quier otro humor? |

.595 |

| 4 | Do you ever want food as a reward for doing something? ¿A veces quieres comida como recompensa por hacer algo? |

.640 |

| 5 | Do you ever sneak or hide food? ¿A veces ocultas comida o la llevas a escondidas? |

.597 |

| Ordinal Alpha | .81 |

Confirmatory validity

Confirmatory Factor Analysis was performed using Diagonally Weighted Least Squares (DWLS) (suitable for ordinal measurement levels).

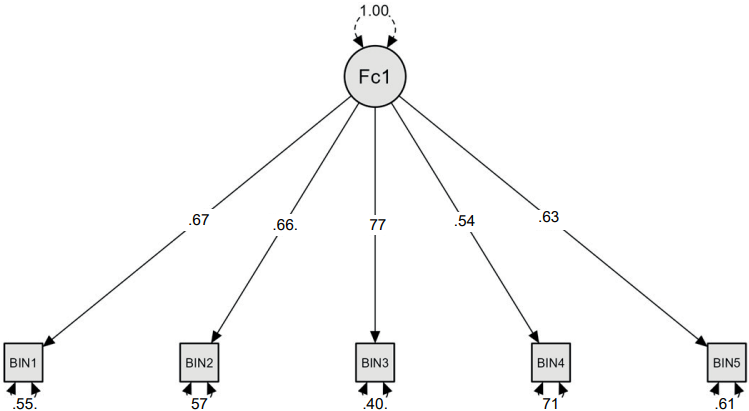

This confirmatory factor analysis showed appropriate goodness of fit indices (CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .000, CI 90% [< .102], GFI = .98, SRMR = .070 Chi2 (Chi2 = 4.81, gl = 5, p = .43). All items showed statistically significant factor loads, with estimates between .53 and .77, and Z values between 5.5 and 7.3 (with p < .001 levels in all cases). (Figure 1)

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

To obtain a self-administered instrument that makes it possible to evaluate binge eating episodes and the risk of BED in children, the self-administered version of the C-BEDS was translated into Spanish, adapted, and administered to Mexican children ages eight to twelve. The psychometric properties of the questionnaire were also obtained.

The SA-C-BEDS provides a new tool in the field of study of eating disorders in children. It is a self-administered instrument that enables cross-cultural research, as well as evaluations for epidemiological studies, making it possible to determine the prevalence and impact of BED-related behaviors in the child population and subsequently develop timely interventions. It is also necessary to have specific instruments for behavior related to loss of control over eating and other behaviors associated with eating disorders, since to date, studies have reported inconsistent prevalence depending on the evaluation instruments used (Tanofsky-Kraff et al., 2004). The SA-C-BEDS has the advantage of being brief. It does not include recall questions that might be difficult to answer in some cases, nor does it have open questions, which can be complicated for children. According to the research conducted, these elements should be considered when evaluating the child population (Marcus & Kalarchian, 2003). In addition, a question should be included on loss of control over eating, which is key in the diagnosis of eating disorders, unlike other instruments that do not include it (Childress et al., 1993; Whitaker et al., 1989). Likewise, adapting it to a self-administered instrument avoids the limitation observed by Franklin et al. (2019), of causing discomfort in subjects when answering an interview.

Although the percentages reported in other studies show trends in response frequency, it is not possible to compare them with our results, because these are samples with distinctive characteristics. For example, the study by Shapiro et al. (2007) involved children interested in participating in a program designed to improve eating habits and physical activity, the majority of whom were overweight and the offspring of obese parents, whereas the study by Dmitrzak-Węglarz et al. (2019) comprised school age children in Poland. In this last study, based on the answers to the C-BEDS items, the authors concluded that 12% of the subjects had a substantial risk of having an ED, which differs from the original authors’ study, which found that 29% of subjects were at substantial risk. Conversely, the meta-analysis conducted by He et al. (2017) shows that the global prevalence of binge eating was 22.2%, while loss of control over eating was 31.2% (He et al., 2017) in studies with both community and clinical samples. One explanation for the discrepancies found is that according to Franco-Paredes et al., (2017) and Gowey et al. (2014), disordered eating behaviors occur more frequently in overweight or obese children, which may be the case in some of the studies reviewed by these authors.

Nationwide, the data provided by ENSANUT, which evaluates DEBs including loss of control while eating, show that in 2006, 18.3% of the population aged ten to nineteen experienced this problem. In 2012, 7% of boys and 5.8% of girls aged between ten and thirteen stated that they were in this situation (Gutiérrez et al., 2012; Olaíz-Fernández et al., 2006; Shamah-Levy et al., 2020). In the present study, this behavior was present in 15.8% of the boys and 15.6% of the girls, with no differences being reported between the participants of the two populations included in the study. These differences are only potential since this is a nationwide survey with multistage sampling and face-to-face data collection rather than a study with convenience sampling conducted online. One of the criteria proposed by Marcus and Kalarchian (2003) for BED is that eating should not be associated with the regular use of inappropriate compensatory behaviors. In the C-BEDS, this criterion is reflected in question seven (getting rid of food). However, when internal consistency was evaluated, it was decided to remove it from the scale since its item-total correlation was less than .20, and it was not concentrated in a factor with at least three items. The five remaining items obtained an ordinal alpha of .81, grouped into a single factor while the confirmatory validity analysis also showed a single factor with adequate factor loads for the five proposed items, and the model fit the data, proving that it is valid.

Although the measurement instruments available to date have made it possible to study the risk of BED in children, further studies are required in both clinical and population contexts to determine their incidence and acquire a deeper understanding of their characteristics and the circumstances surrounding them and undertake preventive actions and intervention programs in several types of population. It is also recommended to expand the study and administer it to more populations in Mexico, ideally with a representative nationwide sample. Achieving this requires having more instruments to assess the risk of BED in children, especially through self-administered instruments. The present study therefore contributes preliminary evidence, specifically the construct validity and adequacy of the scale to the proposed theoretical model through confirmatory analysis, as well as internal consistency, to the study of binge eating with an instrument structured around a single factor for use in population studies to facilitate early detection of the problem.

Limitations of the study include the fact that since it is a self-reported instrument, it is not sufficient to establish a clinical diagnosis of BED. The anthropometric measurements (which would have been useful for characterizing the sample by body weight categories), were based on parents’ reports, reducing their reliability. Other instruments were administered to validate them, which did not enable us to perform convergent or divergent validity analyses. Given the characteristics of the study, no diagnostic interviews were conducted nor was the group compared with a clinical sample. Validations of the scale should therefore be undertaken on its self-reported version in other contexts, which would shed more light on the risk of BED in the child population, as well as convergent, divergent, predictive, test-retest validation and a comparison with clinical samples.

The SA-C-BEDS in Spanish is a valid instrument for measuring specific eating behaviors of BED in the sample studied in two Mexican states (Campeche and Mexico). It is brief and easy to understand and administer. It also provides key information for identifying cases in a timely manner and is useful in the prevention of subsequent BED, as well as related complications.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)