Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista mexicana de fitopatología

versión On-line ISSN 2007-8080versión impresa ISSN 0185-3309

Rev. mex. fitopatol vol.43 no.spe Texcoco 2025 Epub 01-Dic-2025

https://doi.org/10.18781/r.mex.fit.2024-35

Review Articles

Allspice (Pimenta dioica) in Mexico and the use of antagonistic microorganisms for rust and anthracnose control

1Maestría en Ciencias en Manejo Sustentable de Recursos Naturales, Universidad Intercultural del Estado de Puebla. Lipuntahuaca, Huehuetla, Pue., CP 73475, México.

Background/Objective.

The allspice (Pimenta dioica) has different uses as a spice and potential utility in the pharmaceutical and cosmetic industry, making it a species of economic importance. Mexico is the world's second largest producer of this spice, which is cultivated mainly by indigenous peoples. Allspice has a high potential to increase its production in Mexico, due to favorable agroclimatic conditions. However, the presence of diseases, especially anthracnose and rust, is a limitation. The objective was to document the production of allspice in Mexico and to identify management alternatives using antagonistic microorganisms against the occurrence of anthracnose (Colletotrichum sp.) and rust (Austropuccinia psidii).

Materials and Methods.

An exhaustive search was carried out in digital platforms, particularly in Google Scholar, ResearchGate, SciELO and ScienceDirect, for which different combinations of keywords were used to facilitate the search, which were: Pimenta dioica, allspice, diseases, production, cultivation, pimienta and Jamaica pepper in spanish and english. The information was systematized and critically analyzed.

Results

. Allspice production in Mexico has increased in recent years, but it is not sufficient to cover the market. Likewise, information regarding the management of anthracnose and rust in pepper is scarce; however, it has been documented that Bacillus sp., Trichoderma sp., Fusarium sp., Cladosporium sp., Simplicillium sp., Clonostachys sp., Lecanicillium sp., and Streptomyces sp. have antagonistic potential for the management of Colletotrichum sp. and Austropuccinia psidii.

Conclusion.

Research is needed to evaluate the inhibitory capacity of these microorganisms, their mechanisms of action, and their synergistic effect on Colletotrichum sp. and A. psidii under in vitro and field conditions in allspice.

Keywords: Pimenta dioica; Antagonism; Colletotrichum sp.; Austropuccinia psidii

Antecedentes/Objetivo.

La pimienta gorda (Pimenta dioica) tiene diferentes usos como especia y potencial utilidad en la industria farmacéutica y cosmética, por lo que es una especie de importancia económica. A nivel mundial, México es el segundo productor de esta especia, donde su cultivo se realiza principalmente por pueblos originarios. La pimienta gorda tiene un alto potencial para incrementar su producción en México, ya que se cuenta con condiciones agroclimáticas favorables. Sin embargo, una limitante es la presencia de enfermedades, entre las que destacan la antracnosis y la roya. El objetivo fue documentar la producción de pimienta gorda en México e identificar alternativas de manejo mediante microorganismos antagonistas ante la ocurrencia de antracnosis (Colletotrichum sp.) y roya (Austropuccinia psidii).

Materiales y Métodos.

Se realizó una exhaustiva búsqueda en las plataformas digitales, particularmente en Google académico, ResearchGate, SciELO y Science Direct, donde se utilizaron distintas combinaciones de palabras clave para facilitar la búsqueda, las cuales fueron: Pimenta dioica, allspice, enfermedades, producción, cultivo, pimienta gorda y pimienta de Jamaica en español e inglés. La información se sistematizó y analizó críticamente.

Resultados.

La producción de pimienta gorda en México ha aumentado en los últimos años, pero no es suficiente para cubrir el mercado. Así mismo, la información respecto al manejo de la antracnosis y roya en pimienta es escasa, sin embargo, se documentó que Bacillus sp., Trichoderma sp., Fusarium sp. Cladosporium sp., Simplicillium sp., Clonostachys sp., Lecanicillium sp. y Streptomyces sp., tienen potencial antagonista para el manejo de Colletotrichum sp. y Austropuccinia psidii.

Conclusión.

Se requieren investigaciones que evalúen la capacidad de inhibición de estos microorganismos, sus mecanismos de acción y efecto sinérgico sobre Colletotrichum sp. y A. psidii en condiciones in vitro y en campo en pimienta gorda.

Palabras clave: Pimenta dioica; Antagonismo; Colletotrichum sp.; Austropuccinia psidii

Introduction

Since the 16th century, spices have been of great commercial interest worldwide due to their strong potential as preservatives, flavorings, and aromatic agents, as well as for culinary use (Acosta et al., 2021; Macía, 1998). Among the spices that were commonly traded are clove (Syzygium aromaticum), black pepper (Piper nigrum), and nutmeg (Myristica fragans) (Lenkersdorf, 2009). After the discovery of the Americas, new products unknown to the Old World were introduced-one of them was “Pimienta gorda” (Pimenta dioica), used primarily by the Indigenous peoples of the Americas (Acosta et al., 2021), such as the Totonac communities, who used the leaves for seasoning, as medicinal remedies, to scent their homes, and in certain ceremonial rituals. This knowledge has continued to be passed down from generation to generation (Acosta et al., 2021; Jiménez et al., 2015).

“Pimienta gorda” is also known as Jamaican pepper, or in English as “allspice” (Jarquín-Enríquez et al., 2021). In Mexico’s Indigenous languages, it is known as Moque (Zoque, Chiapas), de-tedan (Cuicatec, Oaxaca), malagueta, papalolote (Oaxaca), u'ucum (Totonac, Veracruz), xocoxochitl (Nahuatl), Cukum (Tepehua), and Ixnabacuc (Maya) (Machuca et al., 2020; Macía, 1998; Vázquez-Yanes et al., 1996).

Allspice is an evergreen tree that grows up to 10 m tall, with a dense, rounded or irregular crown. Its fruits are dark-colored berries measuring 5 to 10 mm, flattened at the tip, warty, and distinctively fragrant (Vázquez-Yanes et al., 1996). This tree is native to Mexico and extends into Central America (Montalvo-Lopez et al., 2021). The dried fruit has various uses, such as for flavoring and scenting; its wood is used as fuel, and its leaves are used to prepare infusions (Vázquez-Yanes et al., 1996). The leaves and fruits have been reported to contain volatile organic compounds responsible for their flavor and aroma, which combine notes of cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum), nutmeg (Myristica sp.), and clove (Syzygium aromaticum) (Montalvo-Lopez et al., 2021). Allspice has anesthetic, analgesic, antimicrobial, antioxidant, antiseptic, and acaricidal properties due to phytoconstituents found in different parts of the tree, including phenylpropanoids, glycosides, tannins, and essential oils. In pharmacology, it is valued for its anticancer, antifungal, antimicrobial, nematicidal, antioxidant, and antidiabetic activity (Rao et al., 2012).

Because of these properties, it is considered a high-value product with applications in cosmetics, food preservatives, perfumes, and pharmaceutical products (Martínez et al., 2013; Montalvo-Lopez et al., 2021). The increase in the price of dried allspice has encouraged the formation of cooperatives and organizations dedicated to processing and marketing allspice, as well as the establishment of various collection centers in Veracruz, Puebla, and Chiapas, with Veracruz and Puebla standing out as the leading producers nationwide (Córdoba, 2016; Martínez et al., 2013; Reyes-Martínez, 2017).

However, allspice production is threatened by diseases such as rust caused by Austropuccinia psidii (Beenken, 2017) (formerly Puccinia psidii) and anthracnose (Colletotrichum sp.), which can cause losses of up to 50% of production during both pre- and post-harvest stages (Rojas-Pérez, 2017; Esperón-Rodríguez et al., 2017; Velázquez- Silva et al., 2018). These fungi are mainly controlled with synthetic fungicides from the triazole, strobilurin, or copper groups (Monroy-Rivera, 2011; Gaviria-Hernández et al., 2013). However, the excessive use of synthetic fungicides can lead to chronic soil toxicity, instability in the microbial balance of the agroecosystem, and health risks for farmers (Hernández-Flores et al., 2013; Jáquez-Matas et al., 2022; Silveira-Gramont et al., 2018). Based on the above, the aim of this study was to document allspice production in Mexico and to identify management alternatives using antagonistic microorganisms in response to the occurrence of anthracnose (Colletotrichum sp.) and rust (Austropuccinia psidii).

Allspice Production in Mexico

Allspice (Pimenta dioica) belongs to the order Myrtales and the family Myrtaceae (Tropicos, 2024); in Mexico, it is produced under rainfed conditions as a secondary crop, harvested from wild trees in forests, backyard orchards, as well as in pastures, live fences, windbreak barriers, or intercropped with other crops such as coffee (Coffea arabica), corn (Zea mays), orange (Citrus × sinensis), among others (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Allspice production systems under traditional Totonac management in Lipuntahuaca, Huehuetla, Puebla. A) Monoculture; B) Intercropped with corn; C) Home garden; D) Live fence; E) Coffee grown under allspice shade; F) Acahual (plant associations in areas originally occupied by tropical forests).

Harvesting of the fruit can begin as early as two years after the tree is established and is carried out mainly by hand, climbing the branches to collect the fruits when they are green or yellowish-green, followed by sun-drying (FHIA, 2016). In Mexico, this activity is mainly performed by Indigenous communities or native peoples, harvesting from scattered trees in home gardens, agroforestry systems, and live fences for self- consumption, while the surplus is sold as green allspice (Figure 2) (Machuca et al., 2020; Macía, 1998).

In 1996, in the state of Puebla, the cooperative Tosepan Titataniske set the price of fresh allspice at $2.50 pesos kg⁻¹ and dried allspice at $7.50 pesos kg⁻¹, exceeding the price of coffee cherries, which ranged from $1.70 to $2.80 pesos kg⁻¹. By 2020, the price of allspice as a seasoning ranged between $155.00 and $540.00 pesos kg⁻¹ (Machuca et al., 2020; Macía, 1998).

Figure 2 Allspice production in Lipuntahuaca, Huehuetla, Puebla. A) Harvesting green fruit from allspice trees; B) Sun- drying area for dried fruit; C) Transport of dried allspice fruit.

In 2022, allspice generated economic revenue of $161,377,940.00 pesos in Mexico, with a value ranging from $10,714.00 to $63,641.00 pesos t⁻¹; in 2023, the revenue was $153,210,640.00 pesos, with prices ranging from $10,655.00 to $66,862.00 pesos t⁻¹ (Table 1) (SIAP, 2024).

Table 1 Allspice (Pimenta dioica) production in Mexico during 2022 and 2023.

| State | 2022 | 2023 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Production (t) | Value of production (thousands of pesos) | Production (t) | Value of production (thousands of pesos) | |

| Veracruz | 7,799.08 | 104,427.42 | 7,440.89 | 101,060.90 |

| Puebla | 1,174.10 | 12,580.03 | 1,147.71 | 12,229.23 |

| Tabasco | 975.05 | 30,684.49 | 901.64 | 25,988.78 |

| Campeche | 137.5 | 8,750.77 | 139.9 | 9,354.13 |

| Chiapas | 170.71 | 4,639.90 | 162.77 | 4,330.20 |

| Oaxaca | 8.9 | 295.33 | 7.1 | 247.4 |

| Total | 10,265.34 | 161,377.94 | 9,800.01 | 153,210.64 |

Prepared using data from SIAP (2024).

Allspice production in Mexico has increased in recent years; in 2011, 3,452 t were produced, while in 2023, production reached 9,800.01 t, representing a 183.9% increase (SIAP, 2024; Martínez et al., 2013). Currently, the top three producers nationwide are Veracruz, Puebla, and Tabasco, in that order. These states account for approximately 97% of total national production. Most of the production is exported to the United States (Table 1) (Martínez et al., 2013; SIAP, 2024).

The average yield of allspice is 54 kg per tree. In recent years, a small portion of production has been modernized (Macía, 1998; Martínez et al., 2013; Rojas-Pérez, 2017). However, it is estimated that more than 162,566 ha have high potential for cultivation, while 4,379,623 ha have medium productive potential, mainly in the area of the Trans- Mexican Volcanic Belt (INIFAP, 2012).

Martínez et al. (2013) note that to increase allspice production, plantations must be established in areas with favourable climatic conditions. The states with areas of high productive potential are Veracruz, Puebla, Hidalgo, San Luis Potosí, Guerrero, and Oaxaca (INIFAP, 2012). It is also necessary to develop pathogen-tolerant varieties; ensure proper tree nutrition; improve fruit harvesting methods, as it is currently done manually and often damages the tree; and modernize fruit drying techniques.

It is also important to develop agricultural technologies adapted to small, rugged plots and highly diversified production systems. In addition, phytosanitary issues must be addressed, as there are pathogens that affect allspice production (Esperón-Rodríguez et al., 2017). Likewise, it is essential to pursue sustainable allspice production, taking into account the three components of Nijkamp’s triangle: economic growth, social equity, and environmental sustainability (Zarta-Ávila, 2018).

Phytosanitary issues

Phytosanitary issues are often caused by a combination of environmental, economic, political, and social factors that impact agri-food production (Olvera-Vargas, 2022). In the case of allspice, there are few records of phytosanitary problems, their effects, causal agents, and control measures. However, in Mexico, there are reports of damage caused by Austropuccinia psidii, the agent responsible for rust, and Colletotrichum sp., which causes anthracnose (López and García, 2014; Morales-German et al., 2024; Velázquez- Silva et al., 2018).

Rust in allspice

Rust is the main phytosanitary problem affecting allspice, caused by Austropuccinia psidii (Pucciniales, Basidiomycota). This pathogen belongs to the phylum Basidiomycota, subphylum Pucciniomycotina, class Pucciniomycetes, order Pucciniales, suborder Uredinineae, and family Sphaerophragmiaceae (Mycobank, 2024). It is estimated to cause up to 50% crop loss and develops on the upper and lower leaf surfaces, flower buds, and petioles of young allspice leaves (FHIA, 2008; Morales-German et al., 2024; Rojas-Pérez, 2017). It is primarily associated with species of the Myrtaceae family and is commonly known as “guava and eucalyptus rust” because it also affects those species (López and García, 2014). In Brazil, it has been reported on guava (Psidium guajava), while in New Zealand it has been found on eucalyptus (Eucalyptus spp.) and native species (Metrosideros spp., Lophomyrthus spp., and Kunzea spp.) (Pathan et al., 2020). A. psidii poses a risk to agriculture, forestry, and native species in Mexico, as 192 species of the Myrtaceae family have been identified as susceptible to this pathogen (Esperón-Rodríguez et al., 2017).

Symptoms and signs

Symptoms appear on both the upper and lower surfaces of the leaves, on young petioles, and on the fruits of the host, where circular spots develop ranging in color from purple to brown, with powdery pustules (amphigenous, caulicolous uredinia) that range from yellow to orange at the center of the spots, measuring 0.1-0.6 mm in diameter. These symptoms can cause fruit drop or a loss in fruit quality (Figure 3) (FHIA, 2008; López and García, 2014).

Figure 3 Symptoms and signs of rust (Austropuccinia psidii) in allspice cultivated in Huehuetla, Puebla, Mexico. A and B) Presence of rust on young leaves; C and D) Pustules on the upper side of the leaf; E) Pustules on the underside of the leaf; F) Pustules on the stem; G) Presence of rust on flower buds; H) View of flower buds infected with rust; I) Necrosis and drop of flower buds caused by rust.

The signs of the pathogen appear as echinulate urediniospores (22.26 ± 3.08 × 16.03 ± 1.66 μm), hyaline to yellow, unicellular, and either pyriform, oval, or spherical in shape, with a truncated base (Figure 4) (López and García, 2014; Mohali and Aime, 2016; Morales-German et al., 2024).

Figure 4 Uredinia and urediniospores of rust (Austropuccinia psidii) obtained from plant samples collected in Huehuetla, Puebla. A-C) Visualization of echinulate urediniospores with a truncated base; D) Visualization of uredinia in a cross-section of an allspice leaf.

Management of Austropuccinia psidii using antagonistic microorganisms

Management of rust in allspice is carried out mainly through cultural control (such as proper soil drainage and thinning of wild trees) and chemical control (Table 2) (FHIA, 2008; Martínez et al., 2013; Monroy-Rivera, 2011). However, in Mexico, there are no studies on the effectiveness of synthetic fungicides specifically for managing rust in allspice.

Table 2 Chemical control of Austropuccinia psidii in species of the Myrtaceae family.

| Active ingredient | Trade name | Dose | Host | Country | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mancozeb | Dithane® 43 Sc, Manzate® 200 | 1 Kg/100 L of water | Pimenta gorda | Honduras | FHIA, 2008 |

| Sulfato de cobre | - | 1 Kg/100 L of water | Pimenta gorda | México | Martínez et al., 2013 |

| Cobre | Phyton® 24 SC, Sulcox® 50 WP | 50 mL per hectare | Pimenta gorda | Honduras | FHIA, 2008 |

| Cobre | Nordox® 750 WG | 0.5 g/500 mL of solution | Lophomyrtus x ralphii y Metrosideros excelsa | Australia | Pathan et al., 2020 |

| Cyproconazole y Azoxystrobin Fosetyl aluminum | Amistar Xtar® | 0.5 mL/500 Ml of solution | Lophomyrtus x ralphii y Metrosideros excelsa Lophomyrtus x ralphii y Metrosideros excelsa | Australia | Pathan et al., 2020 |

| Fosetyl aluminum | Aliette® WG | 1.25 mL/500 Ml of solution | Lophomyrtus x ralphii y Metrosideros excelsa Lophomyrtus x ralphii y Metrosideros excelsa | Australia | Pathan et al., 2021 |

| Oxicloruro de cobre | Cupravit® | 2 - 3 g/L of water | Pimenta dioica | México | Monroy-Rivera, 2011 |

| Oxycarboxin | Plantvax® 750 WP | 0.65 g/500 mL of solution | Lophomyrtus x ralphii y Metrosideros excelsa | Australia | Pathan et al., 2020 |

| Tebuconazole | Folicur® 430 SC | 0.15 mL/500 mL of solution | Lophomyrtus x ralphii y Metrosideros excelsa | Australia | Pathan et al., 2021 |

| Triforine | Saporl® | 0.5 mL/500 Ml of solution | Lophomyrtus x ralphii y Metrosideros excelsa | Australia | Pathan et al., 2022 |

| Triadimenol | Bayfidan® 250 | 0.25 mL/500 mL of solution | Lophomyrtus x ralphii y Metrosideros excelsa | Australia | Pathan et al., 2023 |

Background information on the use of antagonistic microorganisms against A. psidii is limited; however, some microorganisms have been reported to reduce the incidence and act as potential biocontrol agents against rusts of the order Pucciniales, suggesting possible antagonistic effects against A. psidii (Table 3).

Table 3 Microorganisms reported as antagonists of rusts belonging to the order Pucciniales.

| Biocontrol agent | Phytopathogen | Host | Conditions | Country | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacillus megaterium and Paneibacillus xylanexedens | Stripe rust of wheat (Puccinia striiformis) | Wheat (Triticum sp.) | Natural environment (semi-field) | Pakistan | Decrease in severity (65.16 and 61.11 % respectively) | Kiani et al., 2021 |

| B. subtilis (Serenade® ASO) | Yellow rust (P. striiformis) | Wheat (Triticum sp.) | Field trials | Denmark | Up to 60% control at moderate disease pressure was reported | Reiss y Jørgensen, 2017 |

| Cladosporium sp. | White rust (P. horiana) | Chrysanthemum (Dendranthema grandiflora) | Laboratory and greenhouse | Mexico | Severity was reduced by 41% to 84% | García- Velasco et al., 2005 |

| Cladosporium angulosum, C. anthropophilum, C. bambusicola and C. benschii, C. guizhouense, and C. macadamiae | Myrtle rust (Austropuccinia psidii) | Myrtaceae family | --- | Brazil | Potential biocontrollers | Pereira et al., 2023 |

| Cladosporium tenuissimum | Uromyces appendiculatus | Phaseolus vulgaris | in vitro in vivo | Italy | Reduction of 17 % of urediniospore germination. Severity decreased to 13 %. | Assante et al., 2004 |

| Cladosporium sp., Alternaria sp. Aspergillus sp. and Trichoderma spp. | U. transversalis | Gladiolus (Gladiolus sp.) | in vitro | Mexico | Colonization percentages ranged from 41.7 to 60.2 % | Romero- Óran et al., 2016 |

| Fusarium fujikuroi, Fusarium solani | Austropuccinia psidii | Malay Apple (Syzygium malaccense) | Laboratory | Brazil | Potential for hyperparasitism | Lopes et al., 2019 |

| Lecanicillium spp., Calcarisporium sp., Sporothrix sp. and Simplicillium spp. | Coffee rust (Hemileia vastatrix) | Coffee (Coffea arabica) | in vitro | Mexico | The percentage of mycoparasitism ranged from 51.6 to 88.8 % | Gómez-De La Cruz et al., 2017 |

| Simplicillium lanosoniveum | Puccinia graminis | Wheat (Triticum sp.) | Artificial climate chamber | China | Urediniospore germination rate of 17%, compared to 91% for the control. | Si et al., 2023 |

| Simplicillium lanosoniveu and Phakopsora pachyrhizi | Phakopsora pachyrhizi | Soybean (Glycine max) | Laboratory and field trials | E.U.A. | The mean number of urediniums produced with the treatment was four times lower compared to the control. | Ward et al., 2012 |

| Trichoderma barbatum and T. asperellum | P. horiana | Chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum morifolium) | Plants in styrofoam cups | Mexico | Rust incidence ranged from 17 to 47 %. | García- Velasco et al., 2022 |

Recently, a study conducted in Brazil evaluated the effect of Bionectria ochroleuca, Cladosporium spp., and two isolates of Clonostachys rosea obtained from Metrosideros polymorpha, Eugenia reinwardtiana, and Syzygium jambos. However, only one of the C. rosea isolates reduced pustule formation by A. psidii and diseased tissue in Eugenia koolauensis (Chock et al., 2021).

Anthracnose in allspice

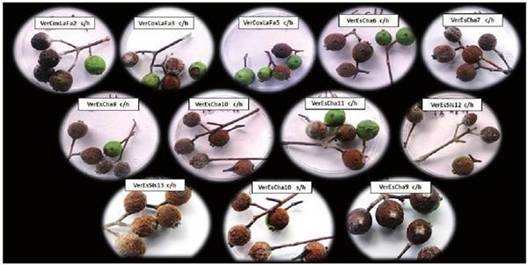

Anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum sp. was first reported in Veracruz, Mexico, in 2018. It belongs to the phylum Ascomycota, subphylum Pezizomycotina, class Sordariomycetes, order Glomerellales, and family Glomerellaceae (Mycobank, 2024). This disease can cause production losses ranging from 20 to 50% during both pre- and post-harvest stages. Symptoms on the fruit include sunken brown or dark spots that lead to fruit necrosis (Figure 5) (Velázquez-Silva et al., 2018).

Figure 5 Symptoms of anthracnose on allspice fruits collected in Veracruz, Mexico. Source: Velázquez-Silva et al. (2018).

In a study conducted by Velázquez-Silva et al. (2018) in northern Veracruz, allspice fruits were collected, from which monospore cultures were obtained and later identified morphologically and molecularly as C. acutatum, C. gloeosporioides, C. fragariae, and

C. boninense.

Control of Colletotrichum sp. using antagonistic microorganisms

Currently, there are no control strategies specifically for anthracnose in Pimenta dioica; however, there are precedents for the control of Colletotrichum sp. in other plant species using biorational products such as plant extracts (Allium sativum, Citrus sinensis and C. grandis, Swinglea glutinosa, Eucalyptus globulus, Piper auritum, Psidium guajava, and Urtica urens), biofungicides, defense inducers, genetic manipulation (Baños-Guevara et al., 2004; Gaviria-Hernández et al., 2013; Landero-Valenzuela et al., 2016), and the use of synthetic fungicides (Table 4).

Table 4 Chemical control for the management of Colletotrichum sp. in different hosts.

| Active ingredient | Trade name | Dose | Host | Country | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azoxystrobin | Amistar® 50 WG | 32 ppm, 250 mg L-1 | Rubus glaucus, Carica papaya | Colombia, Mexico | Gaviria-Hernández et al., 2013; Santamaria et al., 2011 |

| Benomyl | Benoagro® 50 WP, Benocor® Derosal® 500 | 125 ppm | Rubus glaucus | Colombia | Gaviria-Hernández et al., 2013 |

| Carbendazim | SC, Rodazim® 500 sc | 300 ppm | Rubus glaucus | Colombia | Gaviria-Hernández et al., 2014 |

| Clorotalonil | Odeon® 720 SC | Recommended on the label 50ppm | Passiflora edulis, Carica papaya | Ecuador | Carreño et al., 2021 |

| Difenoconazole | Difecor® | 50 ppm | Rubus glaucus | Colombia | Gaviria-Hernández et al., 2013 |

| Hidróxido de cobre | Kocide® 101 | 1230 ppm | Rubus glaucus | Colombia | Gaviria-Hernández et al., 2013 |

| Mancozeb | Dithane M-45 | 1000 ppm | Mangifera indica | Venezuela | Rondón et al., 2006 |

| Propiconazole | Bumper® 25 CE | Recommended on the label | Passiflora edulis, Carica papaya | Ecuador | Carreño et al., 2021 |

| Procloraz | Funcloraz® | 1000 ppm,112 mg L-1 | Carica papaya, Mangifera indica | Venezuela, Mexico | Rondón et al., 2006; Santamaria et al., 2011 |

| Pyraclostrobin | --- | 38.0 and 75.0 mg L-1 i.a | Citrus sinensis | Costa Rica | Guillén-Carvajal et al., 2023 |

| Copper pentahydrate sulfate | Phyton® | Recommended on the label | Passiflora edulis, Carica papaya | Ecuador | Carreño et al., 2021 |

| Tebuconazole | --- | 7.50 y 75.0 mg L- 1 i.a | Citrus sinensis | Costa Rica | Guillén-Carvajal et al., 2023 |

| Tebuconazole + Triadimenol EC 300 | Silvacur Combi® EC300 | --- | Selenicereus | Peru | Bello et al., 2022 |

| Ferbam | --- | 1520 y 3040 mg L-1 i.a | Citrus sinensis | Costa Rica | Guillén-Carvajal et al., 2023 |

For the control of Colletotrichum sp., plant extracts from orange (Citrus sinensis), grapefruit (C. grandis), Swinglea lemon (Swinglea glutinosa), eucalyptus (Eucalyptus globulus), garlic (Allium sativum), and nettle (Urtica urens) have also been used (Gaviria- Hernández et al., 2013). Against Colletotrichum gloeosporioides in yam (Dioscorea spp.), the use of lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) essential oil has been reported (Pérez- Cordero et al., 2017). Other aqueous and ethanolic extracts used for this purpose include extracts from Capparis sinaica, Crotalaria aegyptiaca, Galium sinaica, Plantago sinaica, and Stachys aegyptiaca (Zakaria and Mohamed, 2020).

The effectiveness of antagonistic microorganisms (either endemic or from commercial products) for controlling Colletotrichum sp. isolated from and affecting various crops has also been reported, with their biocontrol potential evaluated both in vitro and in the field (Table 5).

Table 5 Microorganisms reported as antagonists of Colletotrichum sp.

| Biocontrol agent | Phytopathogen | Host | Conditions | Country | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actinobacteria | C. capsici | Chili (Capsicum annuum) | Field trials | Indonesia | Decrease in severity and incidence by 100%. | Yanti et al., 2023 |

| Bacillus amyloliquefaciens (Serenade ASO®) | C. gloeosporioides | Yellow pitaya of Huambo (Selenicereus megalanthus) | in vitro | Peru | Inhibited 100% of mycelial growth. | Bello et al., 2022 |

| Bacillus amyloliquefaciens (Amylo-X®), T. gamsii y T. asperellum (Remedier®), B. amyloliquefaciens (Serenade® ASO), B. pumilus (Sonata®) and T. harzianum (Trianum-P®) | C. acutatum | Olive (Olea europaea) | in vivo | Greece | Inhibition in the production of conidia greater than 40%. | Varveri et al., 2024 |

| Bacillus firmus | C. gloeosporioides | Papaya Maradol (Carica papaya) | in vitro | Mexico | Decreased pathogen growth by 75.32 and 69.17%. | Baños- Guevara et al., 2004 |

| Bacillus subtilis and Rhodotorula minuta | C. gloeosporioides | Mango (Mangifera indica) | Field trial | Mexico | The combination of antagonists reduced the disease (severity of 8.0). | Carrillo et al., 2005 |

| Bacillus sp., Streptomyces sp., Paenibacillus sp. and Gluconobacter cerinus | Colletotrichum sp. | Strawberry (Fragaria sp.) and blueberry (Vaccinium sp.) | in vitro | Mexico | Inhibition percentage from 67.0 to 97.5%. | Garay- Serrano and Pérez, 2024 |

| Nigrospora spp. | C. gloeosporioides | Solanum betaceum | Bioassays | Ecuador | Decrease in damage and significant differences between treated plants versus control. | Delgado y Vásquez, 2010 |

| Paenibacillus sp. | Colletotrichum sp. | Cocoa (Theobroma cacao) | in vitro y field tests | Mexico | Inhibited fungal growth by 30 to 50%. Decreased the incidence of anthracnose. | Rodríguez- Velázquez et al.,2025 |

| Trichoderma asperellum, Trichoderma sp., T. virens (G-41®), T. harzianum (T-22®), Trichoderma sp. (Bactiva®) and Trichoderma sp. (Fithan®) | C. gloeosporioides | Passion fruit (Passiflora edulis) | in vitro | Mexico | The percentage of mycelial growth varied between 72.2 and 88.1%. The percentage of sporulation varied between 97.5 and 100%. | Ayvar- Serna et al., 2024 |

| T. harzianum, T. viride, T. asperellum and Clonostachys rosea | Colletotrichum sp. and C. rosea | Mango (Mangifera indica) | in vitro | Perú | The Percentage Inhibition of Radial Growth Rate (PICR) ranged from 18.2 to 69.4%. | Goñas et al., 2017 |

| Trichoderma lignorum (Mycobac®), Trichoderma harzianum (Agroguard®) and Bacillus subtilis | C. gloeosporioides and C. acutatum | Blackberry (Rubus glaucus) | in vitro | Colombia | Inhibition percentages between 26 and 79 %. | Gaviria- Hernández et al., 2013 |

Modes of action of antagonistic microorganisms

Romero-Orán et al. (2016) reported that Cladosporium sp., Alternaria sp., Aspergillus sp., and Trichoderma spp. caused dehydration, degradation, and deformation of uredinia and urediniospores of Uromyces transversalis. They also observed hyphal invasion of Trichoderma sp. into uredinia of U. transversalis and did not rule out the production of antibiotics, secondary metabolites, and enzymes.

Assante et al. (2004) described the mechanisms of action involved in the mycoparasitism of Cladosporium tenuissimum on Uromyces appendiculatus, reporting enzymatic degradation of both external and internal layers of the urediniospore walls of

U. appendiculatus. They documented urediniospore penetration by short, septate, and highly branched hyphae of Cladosporium tenuissimum, leading to the disappearance of organelles in the urediniospores of U. appendiculatus. They also identified lytic activity during advanced stages of mycoparasitism, resulting in discoloration and thinning of the urediniospore walls, followed by hyphal growth and conidiophore formation on the urediniospores.

Ward et al. (2012) evaluated the biocontrol effect of Simplicillium lanosoniveum on soybean rust (Glycine max) caused by Phakopsora pachyrhizi, reporting changes in the color of uredinia, which may indicate a hypersensitive response of the antagonists against the pathogen.

In bacteria of the genus Bacillus, the mechanisms of action in the biocontrol of phytopathogens include the production of antimicrobial substances, competition for substrates, emission of volatile organic compounds, secretion of lytic enzymes, and induction of resistance (Pedraza et al., 2020). These mechanisms also involve the production of lipopeptides, siderophores, δ-endotoxins, and the activation of systemic acquired resistance (Villarreal-Delgado et al., 2018). A study conducted in Colombia found that the antibiotic Iturin A, produced by B. subtilis, inhibited the growth of Fusarium spp., demonstrating its potential as a phytopathogen control agent (Ariza and Sánchez, 2012). In vitro studies of B. subtilis against Fusarium solani and Pythium sp. showed that the bacterium produces biosurfactant compounds that enable it to exert antifungal activity by destabilizing the cell membranes of the phytopathogens (Sarti, 2019). However, Bacillus species must be assessed for biosafety. Although B. subtilis, B. licheniformis, and B. pumilus are not considered pathogenic to humans, there have been reported cases of foodborne intoxication associated with some species of the Bacillus cereus group (Villarreal-Delgado et al., 2018).

The main modes of action of Trichoderma sp. include competition for space and nutrients, mycoparasitism, and antibiosis, as well as the secretion of enzymes and the production of inhibitory compounds (Infante et al., 2009). Its antimicrobial activity against phytopathogenic fungi is primarily due to a combination of secondary metabolites (terpenes, peptaibols, pyrones, gliovirin, and gliotoxin) and hydrolytic enzymes. Trichoderma sp. also releases substances that induce systemic resistance responses and the expression of defense-related genes (Khan et al., 2020).

Perspectives

Worldwide, there are no studies on the use of antagonistic microorganisms to inhibit

A. psidii and Colletotrichum sp. in allspice. Research on native and endophytic microorganisms antagonistic to these phytopathogens represents a promising line of investigation in Mexico, where allspice agroecosystems remain vulnerable to outbreaks of anthracnose and rust.

It is essential to carry out studies that evaluate the effects of antagonistic microorganisms on the growth and development of Colletotrichum spp. and A. psidii, not only under in vitro conditions but also in terms of their impact on the epidemic development of the diseases under field conditions. These studies must also confirm that the microorganisms are not pathogenic to allspice, which would provide the basis for designing effective management strategies. Some of the microorganisms that could be evaluated include Bacillus spp., Cladosporium spp., Fusarium spp., Simplicillium spp., Trichoderma spp., Paenibacillus spp., Gluconobacter spp., Nigrospora spp., Clonostachys spp., and Streptomyces spp., which have been reported in the management of anthracnose and rust in other plant species.

In addition, it is necessary to deepen the investigation of the mechanisms of action that may be involved, conduct histological studies on the behaviour of antagonists in plant tissue, and perform biochemical analyses of potential secondary metabolites. The use of antagonistic microorganisms is proposed as a viable alternative for the sustainable production of allspice, given that its cultivation in Mexico takes place in diversified agroecosystems, where various plant and animal species coexist, including native species and potentially beneficial microorganisms with antagonistic potential.

Conclusions

Allspice production in Mexico has increased in recent years; however, it remains insufficient to meet both international and domestic market demand, and production remains largely unmechanized across the various production systems. To date, there are no records of in vitro or in situ biocontrol studies targeting Austropuccinia psidii and Colletotrichum sp., the causal agents of rust and anthracnose in allspice, respectively. Various studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of antagonistic microorganisms in controlling other rusts caused by Puccinia spp. in wheat, rose apple, and chrysanthemum, as well as the effectiveness of antagonists in controlling Colletotrichum spp. in tomato, papaya, mango, dragon fruit, and blackberry. Among the microorganisms identified are Bacillus spp., Cladosporium spp., Fusarium spp., Simplicillium spp., Trichoderma spp., Paenibacillus spp., Gluconobacter spp., Nigrospora spp., Clonostachys spp., and Streptomyces spp., among others. However, their modes of action have not been described, nor has their synergistic effect when combined with other microorganisms, and it is still unknown whether any of them could be pathogenic to allspice or have adverse health effects on producers, most of whom belong to Indigenous communities. Therefore, further research is necessary. This article provides information on antagonistic microorganisms that could be evaluated for the management of rust and anthracnose in allspice.

Referencias

Acosta M, Trujillo L, Guadarrama C, Ramírez C y Lima B. 2021. Una mirada desdela sociología delas ausenciasy emergencias a la producción y comercio de pimenta dioica en Zozocolco, Veracruz, México. Brazilian Journal of Development 7:116170-116190. https://doi.org/10.34117/bjdv7n12-398 [ Links ]

Ariza Y y Sánchez L. 2012. Determinación de metabolitos secundarios a partir deBacillus subtiliscon efecto biocontrolador sobreFusariumsp. Nova-Publicación Científica en Ciencias Biomédicas 10:149-155. https://doi.org/10.22490/24629448.1003 [ Links ]

Assante G, MaffiD D, Saracchi M, Farina G, Moricca S,et al. 2004. Histological studies on the mycoparasitism ofCladosporium tenuissimumon urediniospores ofUromyces appendiculatus. Mycological Research 108:170-182. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0953756203008852 [ Links ]

Ayvar-Serna S, Díaz-Nájera J, Valdez-Hernández E, Delgado-Núñez E y Mena-Bahena A. 2024. Antagonismo de cepas nativas y foráneas deTrichodermaspp., contraColletotrichum gleoosporioidescausante de antracnosis en maracuyá. Revista Investigaciones y Estudios - UNA 15:110-116. http://dx.doi.org/10.57201/ieuna2423323 [ Links ]

Baños-Guevara PE, Zavaleta-Mejía E, Colinas-León M, Luna-Romero I y Gutiérrez-Alonso J. 2004. Control Biológico deColletotrichum gloeosporioides[(Penz.) Penz. y Sacc. ] en Papaya Maradol Roja (Carica papayaL.) y Fisiología Postcosecha de Frutos Infectados. Revista Mexicana de Fitopatología 22: 198-205. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=61222206 [ Links ]

Beenken L. 2017. Austropuccinia: A new genus name for the myrtle rustPuccinia psidiiplaced within the redefined family Sphaerophragmiaceae (Pucciniales). Phytotaxa 297:53-61 https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.297.3.14 [ Links ]

Bello S, Echevarría C, Bello N, Borjas-Ventura R, Alvarado-Huamán L,et al. 2022. Controlin vitrodeColletotrichum gloeosporioidesaislado de la pitaya amarilla de Huambo (Selenicereus megalanthus). IDESIA(Chile) 40:75-80. https://doi.org/10.4067/s0718-34292022000300075 [ Links ]

Carreño J, Sánchez L, Guzmán-Cedeño A, Suárez-Palacios C y Vélez-Zambrano S. 2021. EfectoIn Vitrode fungicidas para elcontrol deColletotrichumspp., enfrutales Manabí-Ecuador. RevistaCiencia UNEMI 14:37-42. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/359238020_Efecto_in_vitro_de_fungicidas_para_el_control_de_Colletotrichum_SPP_en_frutales_Manabi_-_Ecuador [ Links ]

Carrillo J, García R, Muy M, Señudo A, Márquez I,et al. 2005. Control biológico de antracnosis [Colletotrichum gloeosporioides(Penz.) Penz. y Sacc. ] y su efecto en la calidad poscosecha del mango (Mangifera indicaL.) en Sinaloa, México. Revista Mexicana de Fitopatología 23:24-32. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=61223104 [ Links ]

Chock M, Hoyt B and Amend S. 2021. Mycobiome transplant increases resistance toAustropuccinia psidiiin an endangered Hawaiian plant. Phytobiome Journal. 5:326-334. https://doi.org/10.1094/PBIOMES-09-20-0065-R [ Links ]

Córdoba P. 2016. Pimienta y mercado diferenciado. In: SAGARPA, Innovarpara competir 40 casos exitosos. pp. 1-30. https://www.redinnovagro.in/casosexito/2017/Pimienta_Asociaciones_A_Serranas.pdf [ Links ]

Delgado E y Vásquez S. 2010. Controlbiológico de la antracnosis causadaporColletotrichum gloeosporioides(Penz. y Sacc.) en tomate de árbol (Solanum betaceumCav.) mediante hongos endófitos antagonistas. La Granja, 11:36-43. https://lagranja.ups.edu.ec/index.php/granja/article/view/11.2010.05 [ Links ]

Esperón-Rodríguez M, Baumgartner J, Beaumont L, Berthon K, Carnegie A,et al. 2017. The risk to Myrtaceae ofAustropuccinia psidii, myrtlerust, in Mexico.Forest Pathology. https://doi.org/10.1111/efp.12428 [ Links ]

FHIA. 2008. Roya dela pimientagorda. Hoja técnica No. 4. 2 p.https://fhia.org.hn/wp-content/uploads/hoja_tecnica_proteccion_vegetal04.pdf [ Links ]

FHIA. 2016. Pimienta gorda:un cultivopara diversificar la producción. FHIA Informa 4:1-12. http://www.fhia.org.hn/descargas/pdfs_fhia-informa/informa_diciembre_2016_4.pdf [ Links ]

Garay-Serrano E y Pérez P. 2024. ActividadAntifúngica de BacteriasContraBotrytis cinereayColletotrichumsp. que Afectan a la Fresa. Biotecnología y Sustentabilidad 9:21-35. http://doi.org/10.57737/jqnnxg27 [ Links ]

García-Velasco R, Martínez-Tapia V, Domínguez-Arizmendi G, Bravo-Luna L y Companioni-González B. 2022. Efecto deTrichodermaspp. sobrela roya blancadel crisantemo inducidaporPuccinia horiana. Acta Agrícola y Pecuaria 8:e0081008. https://doi.org/10.30973/aap/2022.8.0081008 [ Links ]

García-Velasco R, Zavaleta-Mejía E, Rojas- Martinez R, Leyva-Mir S, Kilpatrick-Simpson J,et al. 2005. Antagonismo deCladosporiumsp. contraPuccinia horianaHenn. Causante de la Roya blanca del crisantemo (Dendranthema grandifloraTzvelev). Revista Mexicana de Fitopatología 23:79-86. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/612/61223112.pdf [ Links ]

Gaviria-Hernández V, Patiño-Hoyos L y Saldarriaga-Cardona A. 2013. Evaluaciónin vitrode fungicidas comerciales para el control deColletotrichumspp., en mora de castilla. Revista Corpoica Ciencia y Tecnología Agropecuaria 14:67-75. https://doi.org/10.21930/rcta.vol14_num1_art:344 [ Links ]

Gómez-De La Cruz I, Pérez-Portilla E, Escamilla-Prado E, Martínez-Bolaños M, Carrión-Villarnovo G,et al.. 2017. Selectionin vitroof mycoparasites with potential for biological controlon Coffee Leaf Rust (Hemileia vastatrix). Revista Mexicana de Fitopatología 36 172-183. https://doi.org/10.18781/R.MEX.FIT.1708-1 [ Links ]

Goñas M, Bobadilla L, Roscón J y Vera N. 2017. Efectoin vitrode controladores biológicos sobreColletotrichumspp. YBotrytisspp. Revista de investigaciónde agroproducción sustentable1: 25-31. http://dx.doi.org/10.25127/aps.20172.359 [ Links ]

Guillén-Carvajal M, Umaña-Rojas G y Verela-Benavides I. 2023. Especies deColletotrichumasociados a la antracnosis en naranja (Citrus sinensis(L.) Osb.) y su controlin vitrocon fungicidas. Agronomía Mesoamericana, vol. 34 (https://www.google.com/search?q=%5Bissueno%5D2%5B/issueno%5D). https://doi.org/10.15517/am.v34i2.52190 [ Links ]

Hernández-Flores L, Munive-Hernández A, Sandoval-Castro E, Martínez-Carrera D yVillegas-Hernández C. 2013.Efecto de las prácticas agrícolas sobre las poblaciones bacterianas del suelo en sistemas de cultivo en Chihuahua, México. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas 4:353-365. https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v4i3.1198 [ Links ]

Infante D, Martínez B, González N y Reyes Y. 2009. Mecanismos de acción deTrichodermafrente a hongos fitopatógenos.Revista de Protección Vegetal 24:14-21. https://censa.edicionescervantes.com/index.php/RPV/article/view/542 [ Links ]

INIFAP. 2012. Potencial productivo de especies agrícolas de importancia socioeconómica en México. Publicación especial Núm. 8. 139 p. https://www.cmdrs.gob.mx/sites/default/files/cmdrs/sesion/2018/09/17/1474/materiales/inifap-estudio.pdf [ Links ]

Jarquín-Enríquez L, Ibarra-Torres P, Jiménez-Islas H and Flores-Martínez NL. 2021. Pimenta dioica: a review on its composition, phytochemistry, and applications in food technology. International Food Research Journal 28: 893-904. http://dx.doi.org/10.47836/ifrj.28.5.02 [ Links ]

Jáquez-Matas S, Pérez-Santiago G, Márquez-Linares M y Pérez-Verdín G. 2022. Impactos económicos y ambientales de los plaguicidas en cultivos de Maíz y Nogales en Durango, México. Revista Internacional de Contaminacion Ambiental 38:219-233. https://doi.org/10.20937/RICA.54169 [ Links ]

Jiménez P, Hernández M, Espinosa G, Mendoza G y Torrijos M. 2015. Los saberes en medicina tradicional y su contribución al desarrollo rural: estudio de caso Región Totonaca, Veracruz. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas 6:1791-1805. https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v6i8.496 [ Links ]

Khan RAA, Najeeb S, Hussain S, Xie B and Li Y. 2020. Bioactive secondary metabolites fromTrichodermaspp. Against phytopathogenic fungi. Microorganisms, 8:1-22. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8060817 [ Links ]

Kiani T, Mehboob F, Hyder MZ, Zainy Z, Xu L,et al. 2021. Control of stripe rust of wheat using indigenous endophytic bacteria at seedling and adult plant stage. Scientific Reports 11:1-14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-93939-6 [ Links ]

Landero-Valenzuela N, Lara-Viveros F, Andrade-Hoyos P, Aguilar-Pérez L and Aguado G. 2016. Alternatives for the control ofColletotrichumspp. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas 7:1189-1198. https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v7i5.245 [ Links ]

Lenkersdorf G. 2009. La carrera por las especias. Estudios de Historia Novohispana 17, 13-30. https://doi.org/10.22201/iih.24486922e.1997.017.3452 [ Links ]

López A and García J. 2014. Puccinia psidii(II). Funga Veracruzana. Instituto de Investigaciones Forestales- Universidad Veracruzana. 5 p. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266617679_Puccinia_psidii_II_Uredinales_Pucciniaceae [ Links ]

Lopes V, da Silva A, Vieira P, Tinti N, Morinho R. 2019. Hiperparasitismo deFusariumspp. emAustropuccinia psidiiem Jambo-do-Pará. Summa Phytopathologica 45:204-206. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0100-5405/187593 [ Links ]

Machuca P, Pulido-Salas MT and Trabanino F. 2020. Past and presentof allspice (Pimenta dioica) in Mexico and Guatemala. Revue d’ethnoécologie, 18:1-18. https://doi.org/10.4000/ethnoecologie.6261 [ Links ]

Macía M. (1998). La pimientade Jamaica [Pimenta dioica (L.) Merrill,Myrtaceae] en la Sierra Norte de Puebla (México). Anales Del Jardín Botánicode Madrid 56:337-349. https://digital.csic.es/bitstream/10261/27182/1/234.pdf [ Links ]

Martínez D, Hernández M y Martínez E. 2013. La pimienta gordaen México (Pimenta dioicaL. Merril): avancesy retos en lagestión de la innovación. Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. https://repositorio.chapingo.edu.mx/server/api/core/bitstreams/8f67d11e-b481-448c-acb5-7dff12a8eada/content [ Links ]

Mohali S.R. and Aime M.C. (2016), “First report ofPuccinia psidii(myrtle rust) onSyzygium jambosin Venezuela”, New Disease Reports,Wiley, Vol. 34 No. https://www.google.com/search?q=%5Bissueno%5D1%5B/issueno%5D, pp. 18-18,https://doi.org/10.5197/j.2044-0588.2016.034.018 [ Links ]

Monroy-Rivera C. 2011. Paquete tecnológico pimienta gorda (Pimenta dioicaL. Merril) establecimiento y mantenimiento. https://www.doc-developpement-durable.org/file/Culture/Culture-epices/piment-de-la-Jamaique/Paquete%20Tecnol%C3%B3gico%20Pimienta%20Gorda%20(Pimenta%20dioica).pdf [ Links ]

Montalvo-Lopez I, Montalvo-Hernández D and Molina-Torres J. 2021. Diversity of volatile organic compounds in leaves ofPimenta dioicaMerrill at different developmental stages from fruiting and no-fruiting trees. Journal of the Mexican Chemical Society 65:405-415. https://doi.org/10.29356/jmcs.v65i3.1498 [ Links ]

Morales-German M, Fajardo-Franco ML, Aguilar-Tlatelpa M, Bautista-Hernández G. 2024. Presencia dePuccinia psidiienPimenta dioicacultivada en Huehuetla, Puebla. Revista Mexicana de Fitopatología Suplemento 42:55-56. https://rmf.smf.org.mx/RevistaMexicana/img/RMF/Volumenes/Suplementos/S422024/RMF%20Suplemento%202024.pd f [ Links ]

Mycobank. 2024. Austropuccinia psidii. https://www.mycobank.org/Simplenames search [ Links ]

Nguyen H,Le T, Nguyen T, Truong T and Nguyen T. 2025. BiologicalControl ofStreptomyces murinusagainstColletotrichumCausing Anthracnose Disease on TomatoFruits. J Pure Appl Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.22207/JPAM.19.1.44 [ Links ]

Olvera-Vargas L. 2022. Causas y Consecuencias de problemas fitosanitarios en el café de San Luis Potosí, México. Revista Inclusiones, 9:98-126. https://revistainclusiones.org/index.php/inclu/article/view/3226 [ Links ]

Pathan A, Cuddy W, Kimberly M, Adusei-Fosu K, Rolando C,et al. 2020. Efficacy of applied for protectant and curative activity against myrtle rust. Plant Disease. 104:2123-2129. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-10-19-2106-RE [ Links ]

Pedraza LA, López CE and Uribe-Vélez D. 2020. Mecanismos de acción deBacillussp. (Bacillaceae) contra microorganismos fitopatógenas durante su interacción con plantas. Acta Biologica Colombiana 25:112-125. https://doi.org/10.15446/abc.v25n1.75045 [ Links ]

Pereira N, Cervieri D, Salvador L, Weingart R and Quintão G. 2023. Urveying potentially antagonistic fungi to myrtle rust (Austropuccinia psidii) in Brazil: fungicolousCladosporiumspp. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42770-023-01047-6 [ Links ]

Pérez-Cordero AF, Chamorro-Anaya LM, Vitola-Romero DC y Hernández-Gómez JM. 2017. Actividad antifúngica deCymbopogon citratuscontraColletotrichum gloeosporioides. Agronomía Mesoamericana 28:465. https://doi.org/10.15517/ma.v28i2.23647 [ Links ]

Rao P, Navinchandra S and Jayaveera K. 2012. An important spice,Pimenta dioica(Linn.) Merill: A Review. International Current Pharmaceutical Journal 1: 221-225. https://doi.org/10.3329/icpj.v1i8.11255 [ Links ]

Reiss A and Jørgensen LN. 2017. Biological control of yellow rust of wheat (Puccinia striiformis) with Serenade®ASO (Bacillus subtilis strain QST713). Crop Protection 93:1-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2016.11.009 [ Links ]

Rendón-García G, Ayvar-Serna S, Mena-Bahena A y Díaz-Nájer J. 2020. Controlin vitroconTrichodermaspp., deColletotrichum gloeisporioidesPenz., causante de la antracnosis en Papaya. Foro de EstudiosSobre Guerrero 7:61-64. [ Links ]

Reyes-Martínez A. 2017. Chiapas exportandopimienta gorda. https://www.redinnovagro.in/casosexito/2017/Pimienta_Sociedad_Cooperativa_Pimienta_Jotiquetz.pdf [ Links ]

Rodríguez-Velázquez N, Gómez-de la Cruz I, López-Guillen G, Chavéz-Ramírez B, Estrada-de los Santos P. 2025. Solation and Biological Control ofColletotrichumsp. Causing Anthracnosis inTheobroma cacaoL. in Chiapas, Mexico. Journal of Fung, 11,312. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/jof11040312 [ Links ]

Rojas-Pérez L. 2017. Conocimiento local de la producción dePimenta dioicaen suelosde la región Totonaca de Puebla. Tesis de Maestría. Colegio de Postgraduados http://colposdigital.colpos.mx:8080/jspui/handle/10521/4177 [ Links ]

Romero-Óran E, Aquino-Martínez J, Ramírez-Dávila J y Gutiérrez-Ibáñez A. 2016. Biocontrol in vitro deUromyces transversalis(Thümen) G. Winter (uredinales: puccinaceae) con hongos antagonistas. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas 7 (7):1639-1649. https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v7i7.156 [ Links ]

Rondón O, de Albarracín NS, Rondón A. 2006. Respuestain vitroa la acción de fungicidas para el control de antracnosis,Colletotrichum gleoesporioidesPenz, en frutos de mango. Agronomía Tropical 56:219-235. http://publicaciones.inia.gob.ve/index.php/agronomiatropical/issue/view/64/61 [ Links ]

Santamaria F, Díaz R, Gutiérrez O, Santamaria J y Larqué A. 2011. Control de dos especies deColletotrichumy su efecto sobre el color y sólidos solubles totales en frutos de papaya maradol. Revista Iberoamericana de Tecnología Postcosecha, 12 (https://www.google.com/search?q=%5Bissueno%5D1%5B/issueno%5D): 19-27. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=81318808004 [ Links ]

Sarti G. 2019. Metabolitos con actividad antifúngica producidos por el GéneroBacillus. Terra Mundus 5:40-51. https://publicacionescientificas.uces.edu.ar/index.php/terramundus/article/view/587 [ Links ]

Si B, Wang H, Bai J, Zhang Y and Cao Y. 2023.Evaluating the utilityofSimplicillium lanosoniveum, a hyperparasitic fungus ofPuccinia graminisf. sp. tritici, as a biological control agent against wheat stem rust. Pathogens 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens12010022 [ Links ]

SIAP. 2024. Anuario Estadístico de la Producción Agrícola. 05/05/24. https://nube.agricultura.gob.mx/cierre_agricola/ [ Links ]

Silveira-Gramont M, Aldana-Madrid M, Piri-Santana J, Valenzuela-Quintanar A, Jasa-Silveira G,et al. 2018. Plaguicidasagrícolas: Un marcode referencia para evaluar riesgos a la salud en comunidades ruralesen el estado de Sonora, México.Revista Internacional de Contaminación Ambiental, 34:7-21. https://doi.org/10.20937/RICA.2018.34.01.01 [ Links ]

Tropicos. 2024. Botanical Information System at the Missouri Botanical Garden, Missouri, USA. 05/05/24. Merr. https://www.tropicos.org/name/22101787 [ Links ]

Vázquez-Yanes C, Batis A, Alcocer M, Gual M y Sánchez C. 1996. Pimienta dioica. In: Árboles y arbustos potencialmente valiosos para la restauración ecológica y la reforestación (pp. 198-200). http://www.conabio.gob.mx/conocimiento/info_especies/arboles/doctos/51-myrta2m.pdf [ Links ]

Velázquez-Silva A, García-Díaz SE, Robles-Yerena L, Nava-Díaz C y Nieto-Ángel D. 2018. Primer reporte del géneroColletotrichumspp. en frutos de pimienta gorda(Pimenta dioica) en Veracruz, México.Revista Mexicana de Fitopatología, 36:342-355. https://doi.org/10.18781/r.mex.fit.1711-1 [ Links ]

Villarreal-Delgado M, Villa-Rodríguez E, Cira-Chávez L y Estrada-Alvarado M. 2018. El géneroBacilluscomo agente de control biológico y sus implicaciones en la bioseguridad agrícola. Revista Mexicana de Fitopatología, 36: 95-130. https://doi.org/10.18781/R.MEX.FIT.1706-5 [ Links ]

Ward N, Robertson C, Chanda A and Schneider R. 2012. Effects ofSimplicillium lanosoniveumonPhakopsora pachyrhizi, the soybean rust pathogen, and its use as a biological controlagent. The AmericanPhytopathological Society, 102:749- 760. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-01-11-0031 [ Links ]

Yanti Y, Hamid H, Reflin R, Yaherwandi Y, Nurbailis N, Suriani N, Raddy M and Syahputri M. 2023. Screening of indigenous actinobacteriaas biological control agents ofColletotrichum capsiciand increasing chili production. Egyptian Journal of Biological Pest Control, 33:34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41938-023-00660-9 [ Links ]

Zakaria A and Mohamed M. 2020. In vitroandin vivo, biocontrol activity of extracts prepared from Egyptian indigenous medicinal plants for the management of anthracnose of mango fruits. Archives of Phytopathology and Plant Protection 53:715-730. https://doi.org/10.1080/03235408.2020.1794308 [ Links ]

Zarta-Ávila P. 2018. La sustentabilidad o sostenibilidad: un concepto poderosopara la humanidad. Tabula Rasa, (28), 409-423. https://doi.org/10.25058/20112742.n28.18 [ Links ]

Received: November 20, 2024; Accepted: July 18, 2025

texto en

texto en