Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista mexicana de fitopatología

versión On-line ISSN 2007-8080versión impresa ISSN 0185-3309

Rev. mex. fitopatol vol.43 no.2 Texcoco may. 2025 Epub 29-Jul-2025

https://doi.org/10.18781/r.mex.fit.2405-12

Scientific articles

In vitro sensitivity of Sclerotium rolfsii and four species of Trichoderma to common-use fungicides on the potato (Solanum tuberosum) crop

1Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa, Colegio de Ciencias Agropecuarias, Facultad de Agricultura del Valle del Fuerte, Calle 16 S/N Esquina Japaraqui, Juan José Ríos, El Estero, Sinaloa, México. C. P. 81110.

2Junta Local de Sanidad Vegetal del Valle del Fuerte; Lázaro Cárdenas, 315 Pte. Col. Centro, Los Mochis Sinaloa, México C. P. 81200.

3Universidad Autónoma de Occidente, Unidad Los Mochis, Departamento de Ciencias Naturales y Exactas, Boulevard Macario Gaxiola y Carretera Internacional S/N Los Mochis, Sinaloa, México. C. P. 81223.

Background/Objective

. Soft rot of potato tubers, caused by Sclerotium rolfsii, is a disease that occurs in soils with high levels of humidity and temperatures above 30 °C. Synthetic fungicides are primarily used for its control. The objectives of this study were to determine the biological efficacy of synthetic fungicides at different concentrations against the pathogen and the sensitivity of four species of Trichoderma to commonly used fungicides in potato in Sinaloa.

Materials and Methods.

The in vitro efficacy of nine fungicides at concentrations of 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10 and 100 ppm on mycelial growth inhibition and sclerotia formation of S. rolfsii was determined. Furthermore, the in vitro sensitivity of T. afroharzianum, T. asperelloides, T. asperellum, and T. azevedoi to 10 fungicides at concentrations of 100, 500, 1000, and 2000 ppm was studied. The experiment was conducted twice. Treatments were distributed in a completely randomized design and data were subjected to ANOVA. Means were compared with the Tukey test (p < 0.05).

Results

. Thifluzamide and Propineb at the 0.01 ppm concentration inhibited mycelial growth S. rolfsii by 32.7 and 12.2%, respectively. On the other hand, S. rolfsii produced 157, 164, and 164 sclerotia per Petri dish on PDA supplemented with the fungicides. Thifluzamide, Propineb and prochloraz, respectively, at the same concentration. In contrast, Propineb at a concentration of 100 ppm inhibited the mycelial growth of T. azevedoi, T. afroharzianum, T. asperellum and T. asperelloides by 0, 0, 0 and 54.9%, respectively; while the inhibition of mycelial growth by Thifluzamide at the same concentration in T. azevedoi, T. afroharzianum, T. asperellum and T. asperelloides ranged from 0 to 63%. The results indicate that the four Trichoderma species are compatible with both fungicides.

Conclusion

. The effect of thifluzamide and propineb on mycelial growth inhibition and sclerotia formation of S. rolfsii, as well as their compatibility with the four species Trichoderma, indicates that the combination of Trichoderma spp. and the fungicides has potential use for controlling soft rot of potato tubers under field conditions.

Keywords: Production; Quality; Sclerotia; Management.

Antecedentes/Objetivo.

La pudrición blanda de tubérculos de papa, causada por Sclerotium rolfsii, es una enfermedad que se presenta en suelos con altos niveles de humedad y temperaturas superiores a los 30 °C. Para su control se usan principalmente fungicidas sintéticos. Los objetivos del presente trabajo fueron determinar la efectividad biológica de fungicidas sintéticos a diferentes concentraciones contra el hongo y la sensibilidad de cuatro especies de Trichoderma a fungicidas de uso común en papa en Sinaloa.

Materiales y Métodos.

Se determinó la efectividad biológica in vitro de nueve fungicidas a las concentraciones de 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10 y 100 ppm contra el crecimiento micelial y formación de esclerocios de S. rolfsii; además, se determinó la sensibilidad in vitro de Trichoderma afroharzianum, T. asperelloides, T. asperellum y T. azevedoi a 10 fungicidas en las concentraciones de 100, 500, 1000 y 2000 ppm. Los experimentos se repitieron dos veces. Los tratamientos se distribuyeron en un arreglo completamente al azar cuyos datos se sometieron a ANOVA. La comparación de medias fue mediante la prueba de Tukey (p<0.05).

Resultados.

Tifluzamida y Propineb a la concentración de 0.01 ppm inhibieron el crecimiento micelial de S. rolfsii en 32.7 y 12.2 %, en forma respectiva. Por otro lado, S. rolfsii produjo de 157, 164 y 164 esclerocios por caja de Petri en PDA adicionado con los fungicidas Tifluzamida, Propineb y procloraz, respectivamente a la misma concentración. En cambio, Propineb a la concentración de 100 ppm inhibió el crecimiento micelial de T. azevedoi, T. afroharzianum, T. asperellum y T. asperelloides de 0, 0, 0 y 54.9 %, en forma respectiva; mientras que la inhibición de crecimiento micelial por Tifluzamida a la misma concentración en T. azevedoi, T. afroharzianum, T. asperellum y T. asperelloides varió de 0 a 63 %. Los resultados indican que las cuatro especies de Trichoderma son compatibles a ambos fungicidas.

Conclusión.

El efecto de Tifluzamida y Propineb en la inhibición del crecimiento micelial y la formación de esclerocios de S. rolfsii, así como la compatibilidad con las cuatro especies de Trichoderma con estos fungicidas, indica que la mezcla de Trichoderma spp. + los fungicidas, muestra un uso potencial para el control de la pudrición blanda del tubérculo de papa en campo.

Palabras clave: Producción; Calidad; Esclerocios; Manejo

Introduction

The potato (Solanum tuberosum) is the sixth most widely produced crop in the world, with 470,409,159 t, obtained from 23,514,508 h. The main producing countries of this tuber are China, India, Ukraine, Russia and the United States (FAO, 2023). Mexico is in35th place, with an annual production of 1,986,198 t, with the highest-producing states are Sonora, with 612,600 t, and Sinaloa with 427,587 t a year, representing 52.4% of the national production, with a production valued in 17,426,448,000 pesos (SIAP, 2023). The crop is affected by diseases that limit its production and quality (Torrance and Talianksy, 2020; Singh et al., 2021). Soft rot stands out for its importance and is caused by Sclerotium rolfsii, which affects around 500 plant species, which are grouped into 100 different families, with tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), cucumber (Cucumis sativus), peanut (Arachis hypogaea), potato and others standing out (Kator et al., 2015; Roca et al., 2016; Kumar et al., 2018; Paparu et al., 2020; Meena et al., 2023). In the potato, soft tuber rot affects production by 20%. The fungus presents saprophytic habits and in the soil it colonizes crop residues or it can survive in the form of sclerotia, which are dispersed through water, machinery, plant residues, soil and animales (Kator et al., 2015; Roca et al., 2016).

The traditional management of tuber soft rot with synthetic fungicides contaminates the environment and affects living beings (Widmer, 2019), and its continuous use produces resistance in phytopathogens, which leads to the increase in concentrations for their control (Ferreira et al., 2020).

In recent years, advances have emerged regarding the use of environmentally friendly strategies for disease management in various crops, with the use of fungi as biological control agents standing out (Rubayet and Bhuiyan 2016; Yassin et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2023)

The fungi genus of the Trichoderma are the most widely studied and used as biological agents, due to the good results in the control of fungal diseases. This is due to the diversity of action mechanisms they have (competition for space and nutrients, mycoparasitism and antibiosis). In addition, this type of antagonistics produce secondary metabolites that promote plant growth and activate the defense mechanisms of plants, as well as increasing crop production and quality (Yao et al., 2023). Treatments with this fungus are directed to seed, seedlings, irrigation water and foliage; on the other hand, there are studies in which the compatibility of Trichoderma with commercial synthetic fungicides has been proven for use in mixtures in the control of fungal diseases in diverse crops (Gonzalez et al., 2020; Manandhar et al., 2020; Arain et al., 2022; Dinkwar et al., 2023).

In Mexico there are no studies on the compatibility of Trichoderma species in mixtures with fungicides aimed at the control of soft potato tuber rot. For this reason, the aim of this study was to determine the in vitro biological effectiveness of different concentrations of synthetic fungicides on the inhibition of mycelial growth and formation of S. rolfsii sclerotia, as well as the in vitro effect of the fungicides on the mycelial growth of Trichoderma afroharzianum, T. asperelloides, T. asperellum and T. azevedoi.

Materials and Methods

Origen of isolates. S. rolfsii (Scr4) Trichoderma afroharzianum (TES24), T. asperelloides (TAM74), T. asperellum (TAF75) and T. azevedoi (TAI73) were provided by the microbiological bank of the Phytosanitary Diagnostics Laboratory of the Local Plant Health Board of the El Fuerte Velley. The isolates were obtained from soil in commercial fields in which potato was grown in previous agricultural cycles in the Municipalities of Ahome, Sinaloa and, Altar and Caborca in Sonora, Mexico in 2019, 2020 and 2021 (Table 1).

Table 1 Species and isolates of Sclerotium rolfsii and Trichoderma, site and year of collection and code in the GeneBank.

| Species/isolate | Locality | Year of collection | Code in GeneBank |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sclerotium rolfsii /Scr4 | Ahome, Sinaloa/ 25.701944 -109.043333 | 2019 | OR514113 |

| T. asperelloides /TES24 | Caborca, Sonora/31.06666 -112.338333 | 2020 | OR521164 |

| T. azevedoi /TAI73 | Ahome, Sinaloa/25.818885 -108.956014 | 2021 | OR521181 |

| T. afroharzianum/TAF75 | Ahome, Sinaloa/25.491445 -108.571659 | 2021 | OR521183 |

| T. asperellum/TAM74 | Ahome, Sinaloa/ 25.491445 -108.571659 | 2021 | OR521182 |

In vitro sensitivity of Sclerotium rolfsii to nine synthetic fungicides. This study evaluated the in vitro sensitivity of S. rolfsii (isolate Scr4) to the following fungicides: Thifluzamide (Summit Agro Mexico), Thiabendazole (Arysta LifeScience Mexico), Mancozeb (Arysta LifeScience Mexico), Propineb (Bayer Crop Science), Prochloraz (Adama, Mexico), Propiconazole (Syngenta Agro), Tolclofos-methyl (Valent), Carboxin+Captan (Arysta LifeScience) and Thiophanate-methyl (Arysta LifeScience), against the mycelial growth of the fungal isolate.

The tests were performed using the poisoned food technique (Dinkwar et al., 2023), in Petri dishes, 90 mm in diameter, with 20 mL of the Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) culture medium, supplemented with the test substances at the concentrations of 0.01, 0.1, 1.0, 10 and 100 ppm. PDA discs (5 mm in diameter) with a three-day active mycelial growth of S. rolfsii were used and transferred to the center of the Petri dish. The treatments were distributed in a completely randomized design with a 9x5 factorial arrangement, in which the first factor of the arrangement was each one of the nine fungicides and the second factor consisted of the five concentrations. The dishes were sealed with parafilm and incubated at 25 ±2 °C. The control consisted of five Petri dishes with PDA and fungal mycelium without fungicide.

The biological effectiveness of the fungicides on the mycelial growth of S. rolfsii was determined by measuring radial growth of the fungus every 24 h, after its transfer and ended when S. rolfsii filled the Petri dishes without any fungicide.

The percentage of inhibition of the mycelial growth of S. rolfsii was calculated according to the equation I= C-T/C X 100, where I=Percentage of inhibition, C=Growth of the control pathogen, T=Growth of the pathogen under treatment (Vincent, 1947). The experiment was performed twice.

Effect of synthetic fungicides on the formation of sclerotia by S. rolfsii. PDA discs, 5 mm in diameter with an active S. rolfsii mycelial growth were transfered onto PDA Petri dishes containing fungicides in the same concentrations described in the previous section. The design of the treatments was completely at random with a 9x5 factorial arrangements, with five replicates, in which the first factor of the arrangement was each one of the nine fungicides and the second factor was the five concentrations. The control treatment consisted of five Petri dishes with PDA with S. rolfsii mycelial growth without any fungicide. The number of sclerotia was determined 21 days of incubatiton. The experiment was performed twice.

In vitro sensitivity of Trichoderma to 10 synthetic fungicides. This study evaluated the in vitro sensitivity of T. afroharzianum, T. asperelloides, T. asperellum and T. azevedoi to the fungicides 1) Thifluzamide (Summi Agro Mexico), 2) Thiabendazole (Arysta LifeScience Mexico), 3) Mancozeb (Arysta LifeScience Mexico), 4) Propineb (Bayer Crop Science), 5) Prochloraz (Adama, Mexico), 6) Propiconazole (Syngenta Agro), 7) Carboxin+Captan (Arysta LifeScience Mexico), 8) Thiophanate-methyl (Arysta LifeScience), 9) Fluazinam (Syngenta Agro) and 10) TCMTB (Summit Agro Mexico).

The trial was performed based on procedures described by Dinkwar et al. (2023), and for this purpose, Petri dishes with a diameter of 90 mm and 20 mL of PDA containing the test substances were used in the following concentrations: 100, 500, 1000 and 2000 ppm. PDA discs, 5 mm in diameter with an active mycelial growth of each species of Trichoderma were used, which were placed in the center of the Petri dish. The treatments were distributed in a completely randomized experimental design and with a 4x10x4 factorial arrangement, with four repetitions, in which the first factor of the arrangement corresponded to each one of the Trichoderma species, the second one was the 10 fungicides and the third one, the four concentrations of fungicides. The dishes were sealed with parafilm and incubated at 25±2 °C. The control consisted on four Petri dishes with PDA with the Trichoderma species without fungicide. The experiment was performed twice.

The biological effectiveness of the fungicides on the mycelial growth of the four Trichoderma species was determined by measuring their radial growth every 24 h after during the experimental period and culminated when each of the Trichoderma species filled the Petri dishes without fungicide.

The percentage of inhibition of the mycelial growth of the Trichoderma species was calculated according to the formula I= C-T/C X 100, where I=Percentage of inhibition, C=Growth of the control antagonist, T=Growth of the antagonist under treatment (Vincent, 1947).

Statistical analysis of data. Considering that the data of the experiments 1 and 2 on the inhibition of the radial growth and the production of sclerotia by S. rolfsii in the different concentrations of the fungicides did not display significant differences between them, in addition to their variances being homogenous, the data of both experiments were combined, analyzed as a single one. The data were subjected to an ANOVA in the statistical package (SAS 9.0, SAS Institute Inc., North Carolina, USA). The comparison of means was performed using Tukey’s test (P=0.05) (Little and Hills, 1973). The data on the inhibition of mycelial growth of the four Trichoderma species by the fungicides were subjected to the same statistical analyses.

Results

Biological in vitro effectiveness of synthetic fungicides in the inhibition of mycelial growth in Sclerotium rolfsii. The factorial variance analysis between fungicides displayed significant differences (F=65687.3, P≤ 0.0001). Significant differences (F=141381, P≤ 0.0001) were also reflected between fungicidal concentrations. The interaction of fungicides and their concentrations was also significant (F=9142.35, P≤ 0.0001), which implies a differential sensitivity of S. rolfsii to the concentrations of the fungicides under study (Table 2).

Table 2 Factorial analysis of variance of the percentage of in vitro inhibition of the mycelial growth in S. rolfsii to four concentrations of nine fungicides.

| Source | Sdf | SSum of squares | SF values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fungicides | 8 | 174055.4360z | 65687.3b |

| Concentrations of fungicides | 4 | 187313.2096 | 141381 |

| Fungicides X concentrations of fungicides | 32 | 96900.0220 | 9142.35 |

zThe analysis of variance was performed with data transformed into the Arc sin-

1 form, using Type III sum of squares from SAS’s generalized linear model (GLM) procedures. b= Significant effect at P≤ 0.0001.

The inhibition of the mycelial growth of S. rolfsii by the fungicides Tifluzamide, Propineb and Propiconazole at the concentration of 0.01 ppm varied between 5.7 and 32.7%, with significant differences (P = 0.05) between treatments, whereas the rest of the fungicides at the same concentrations exerted no inhibition in the mycelial growth of the fungus, while the inhibition exerted by the fungicides Thifluzamide, Carboxin+Captan, Propiconazole, Propineb, Prochloraz and Thiabendazole at 0.1 ppm concentrations varied between 6.8 and 78.1%, with significant differences (P=0.05) between them. In turn, the treatments displayed differences with the rest of the fungicides, where there was no inhibition of the mycelial growth of the fungus (Table 3).

The fungicides Thifluzamide, Propineb, Propiconazole, Carboxin+Captan, Tolclofos-methyl, Prochloraz and Thiabendazole, at a concentration of 1 ppm, inhibited the mycelial growth by 7.1-93.1%, with significant differences (P=0.05) between treatments. Thifluzamide and Carboxin+Captan stand out for their biological effectiveness, whereas Mancozeb and Thiophanate methyl did not inhibit the mycelial growth of the fungus (Table 3).

Table 3. Average percentage of in vitro inhibition of the radial growth of Sclerotium rolfsii, caused by various synthetic fungicides.

| Percent of inhibition of mycelial growth | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ppm | |||||||||

| Tifz | Prop | Prp | C+C | Prc | Tia | Tol | Man | Tio | |

| 0.01 | 32.7* a** | 12.2 b | 5.7 c | 0.0 d | 0.0 d | 0.0 d | 0.0 d | 0.0 d | 0.0 d |

| 0.1 | 78.1 a | 15.0 d | 18.2 c | 64.2 b | 14.0 d | 6.8 e | 0.0 f | 0.0 f | 0.0 f |

| 1.0 | 90.7 b | 16.0 e | 48.0 d | 93.1 a | 15.8 e | 7.1 f | 61.4 c | 0.0 g | 0.0 g |

| 10 | 92.4 b | 26.9 d | 100 a | 100 a | 33.0 c | 17.5 f | 100 a | 20.7 e | 6.6 g |

| 100 | 93.0 b | 41.1 d | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | 20.9 e | 100 a | 75.0 c | 8.1 f |

zTif =Thifluzamide, Pro = Propineb, Prp= Propiconazole, C+C = Carboxin+Captan, Prc = Prochloraz, Tia = Thiabendazole, Tol = Tolclofos-methyl, Man = Mancozeb and Tio =Thiophanate-methyl.

*The number in the row expresses the average percentage of mycelial growth inhibition in S. rolfsii for each one of the fungicides. **Means with a common letter in the rows are not significantly different (P=0.05) when placed under Tukey’s test.

The concentration of 10 ppm in all fungicides inhibited the mycelial growth of the fungus, with Propiconazole, Carboxin+Captan and Tolclofos-methyl standing out for their efficiency, since they inhibited 100% of the mycelial growth with no significant differences (P=0.05) between these treatments, although there were differences compared to the other fungicides, where mycelial growth ranged from 6.6 to 92.4%, with Thifluzamide showing the greatest inhibiting effect (Table 3).

The inhibition of the mycelial growth of S. rolfsii by fungicides Tifluzamide, Propiconazole, Carboxin+Captan, Prochloraz y Tolclofos-methyl at a concentration of 100 ppm was evident, with inhibitions of the mycelial growth of 93.0 to 100%, with significant differences (P=0.05) among these treatments. The mycelial inhibition by the fungicides Propineb, Tiabendazol, Mancozeb and Thiophanate-methyl varied from 8.1 to 75.0% with significant differences (P=0.05) among them and also with the rest of the fungicides (Table 3)

In vitro effect of synthetic fungicides on the in vitro formation of Sclerotium rolfsii sclerotia. Significant differences (F=2524.74, P≤ 0.0001) were reflected in the production of S. rolfsii sclerotia in PDA with the different chemical fungicides. The five concentrations also displayed significant differences (F=10146.5, P≤ 0.0001) in the productions of the fungal resistance structures. The interaction between the fungicides and their concentrations was also significant (F=642.22, P≤ 0.0001) (Table 4).

The production of sclerotia varied between 157 and 180 per Petri dish in PDA with the different fungicides in the concentration of 0.01 ppm. The lowest number of slcerotia occurred in the culture medium with Thifluzamide, Propineb and Prochloraz, whcih displayed no significant differences (P=0.05) between them, but there were differences with the rest of the fungicides and the control without fungicide, where 182 sclerotia were counted for each Petri dish (Table 5).

Table 4 Factorial analysis of variance of sclerotia production by S. rolfsii in PDA with five concentrations of nine fungicides.

| Source | df | Sum of squares | F values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fungicides | 9 | 386.840642* | 2524.74b |

| Concentrations of fungicides | 4 | 1554.645170* | 10146.5 |

| Fungicides X concentrations of fungicides | 36 | 98.400870* | 642.22 |

*The analysis of variance was carried out with data transformed to the square root form using type III of the sum of squares in SAS’s GLM procedures. b= Significant effect at P≤ 0.0001.

The concentration of 0.1 ppm of Thifluzamide and Carboxin+Captan exerted the greatest effect in the inhibition of the formation of sclerotia with 147 and 148, respectively for every Petri dish. In the rest of the treatments, the production of sclerotia varied between 161 and 171, with significant differences (P = 0.05) between them.

Sclerotium rolfsii formed no sclerotia in the concentration of 1 ppm of Thifluzamide, although the number of sclerotia for each Petri dish varied between 69 and 162 in the culture medium with the same concentration in the different fungicides. There were significant differences (P = 0.05) between these treatments and with the control treatment, where 182 sclerotia were produced per Petri dish.

No sclerotia were formed in PDA with the concentration of 10 ppm of Thifluzamide, Propineb and Carboxin+Captan, but they did form in the medium with the rest of the fungicides at the same concentration, with significant differences (P = 0.05) between treatments, where the number of sclerotia varied between 22 and 146 per Petri dish. The lowest efficiency was displayed by Thiabendazole, since this treatment displayed the lowest number of sclerotia.

Table 5 Production of Sclerotium rolfsii sclerotia per Petri dish with PDA added with the different concentrations of nine fungicides.

| Fungicides/number of sclerrotia | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ppm | ||||||||||

| Tify | Prc | Pro | Tol | Prp | C+C | Tia | Man | Tio | Tes | |

| 0.01 | 157 c* | 164 cb | 164 cb | 171 a | 173 ab | 174 ab | 174 ab | 178 a | 180 a | 182 a |

| 0.1 | 147c | 162 cb | 163 abc | 164 abc | 171 ab | 148 c | 167 ab | 161 cb | 162 cb | 182 a |

| 1 | 0 e | 92 c | 69 d | 148 b | 162 b | 93 c | 161 b | 78 d | 148 b | 182 a |

| 10 | 0g | 75 d | 0 g | 30 e | 129 c | 0 g | 146 b | 22 f | 131 c | 182 a |

| 100 | 0 d | 0 d | 0 d | 9 c | 0 d | 0 d | 132 b | 0 d | 129 b | 182 a |

yTif =Tifluzamide, Prc = Prochloraz, Pro = Propineb, Tol = Tolclofos-methyl, Prp= Propiconazole, C+C = Carboxin+Captan, TC = TCMTB, Tia = Thiabendazole, Man = Mancozeb, Flu = Fluazinam, Tio =Thiophanate-methyl and control without fungicide. zSclerotia in PDA with different concentrations of fungicides 21 days of incubation. *Means with a common letter in the rows are not significantly different (P=0.05) according to Tukey’s procedure.

In the concentration of 100 ppm of Thifluzamide, Prochloraz, Propineb, Propiconazole, Carboxin+Captan and Mancozeb completely inhibited the formation of sclerotia, without any significant differences (P=0.05) between treatments, although there were differences with the number of sclerotia (9 to 132) produced in the medium with the fungicides Tolclofos-methyl, Thiabendazole and Thiophanate-methyl at the same concentration.

In vitro sensitivity of four Trichoderma species to 10 synthetic fungicides. In the factorial analysis of variance, the four Trichoderma species displayed significant differences (F=9576.97, P≤ 0.0001) in the percentage of inhibition of the mycelial growth. The species of the fungus displayed a differential response to the fungicides included in this study. Likewise, the 10 fungicides displayed significant differences (F=177350, P≤ 0.0001) in the inhibition of the Trichoderma species. There were also significant differences (F=24772.8, P≤ 0.0001) between the concentrations. The interaction between the 10 fungidides and their four respective concentrations was also significant (F=5208, P≤ 0.0001). Similarly, the interaction of the Trichoderma species and the 10 fungicides was also significant (F=4212.90, P≤ 0.0001). The interaction between the species of Trichoderma and the four concentrations of fungicide evaluated displayed significant differences (F=1173.88, P≤ 0.0001). Finally, the interaction Trichoderma species X fungicides X concentrations of fungicides was also significant (1211.06, P≤ 0.0001) (Table 6).

Table 6 Factorial analysis of variance of the percentage of in vitro inhibition of the mycelial growth of four Trichoderma species by four concentrations of ten fungicides.

| Source | gl | Sum of squares | values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Species of Trichoderma | 3 | 4044.8603* | 9576.97b |

| Fungicides | 9 | 74904.1540* | 177350 |

| Concentrations of fungicides | 3 | 10462.8481* | 24772.8 |

| Fungicides X concentrations of fungicides | 27 | 2199.9104* | 5208.70 |

| Species of Trichoderma X fungicides | 27 | 1779.3305* | 4212.90 |

| Species of Trichoderma X concentrations of fungicides | 9 | 495.7913* | 1173.88 |

| Species of Trichoderma X fungicides X concentrations of fungicides | 81 | 511.4926* | 1211.06 |

*The analysis of variance was performed with data transformed into the Arc sen-1 form, using Type III sum of squares from SAS’s GLM procedures. b= Significant effect at P≤ 0.0001.

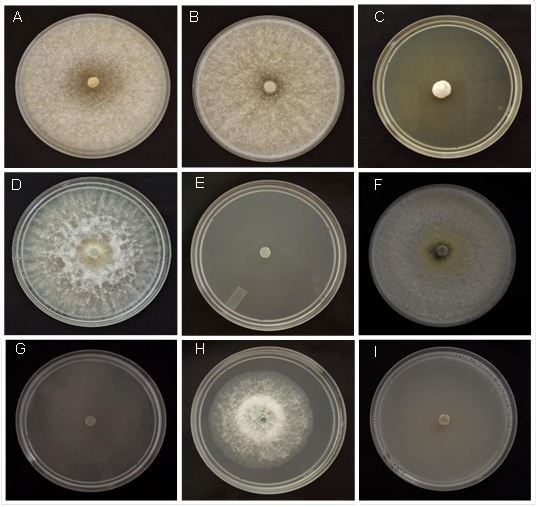

The fungicides Propineb and Tifluzamide at a concentration of 100 ppm did not lead to an in vitro inhibition of the mycelial growth of T. azevedoi (Figure 1 A and B); the rest of the fungicides inhibited mycelial growth from 30.8 to 100%, with significant differences between treatments (P=0.05). T. azevedoi displayed sensitivity to 2000 ppm, particularly in the case of Propineb. Increasing the concentrations of 500 to 2000 ppm led to an increased inhibition of the mycelial growth by Thifluzamide, but without completely inhibiting the mycelial development. By contrast, Fluazinam (Figure 1 C) and the rest of the fungicides inhibited the mycelial development of T. azevedoi from

88.9 to 100%, with significant differences (P=0.05) between treatments (Table 7).

Similar to T. azevedoi, T. afroharzianum displayed no sensitivity to Propineb in the concentrations of 100 (Figure 1 D), 500 and 1000 ppm, although it did display a sensitivity to 2000 ppm. The inhibition of the mycelial growth of T. afroharzianum increased gradually when increasing the concentrations of the fungicides Thifluzamide, Mancozeb, Caboxin+Captan and Fluazinam. The fungicides Propiconazol (Figure 1 E), Prochloraz, Thiabendazole and Thiophanate-methyl at concentrations of 100 to 2000 ppm inhibited 100% of the mycelial growth of the antagonist.

Figure 1 Inhibition of the mycelial growth of four Trichoderma species in PDA added with synthetic fungicides. A) T. azevedoi+Propineb 100 ppm; B) T. azevedoi+Tifluzamide 100 ppm; C) T. azevedoi+Fluazinam 100 ppm; D) T. afroharzianum+Propineb 100 ppm; E) T. afroharzianum+Propiconazole 100 ppm; F) T. asperellum+Propineb 100 ppm; G) T. asperellum+Thiabendazole 100 ppm; H) T. asperelloides+Tifluzamide 100 ppm; I) T. asperelloides+TCMTB 100 ppm.

The fungicides Propineb (Figure 1 F) and Thifluzamide at concentrations of 100 and 500 ppm ndid not exert an in vitro inhibiting effect on the mycelial growth of T. asperellum. The fungus only displayed sensitivity to the concentrations of 1000 and 2000 ppm of both fungicides, whereas Mancozeb and Carboxin+Captan inhibited mycelial growth by 36.7 to 92.2%. The rest of the fungicides exerted an in vitro inhibition of 95.0 to 100% (Table 7; Figure 1 G), regardless of their concentrations.

Table 7 Means of percentage of in vitro inhibition of the radial growth of four Trichoderma species, caused by various synthetic fungicides.

| ppm | Percent of inhibition of mycelial growth | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proz | Tif | Man | C+C | Flu | TC | Prp | Prc | Tia | Tio | ||

| T. azevedoi | 100 | 0.0 e | 0.0 e | 30.8 d | 73.0 c | 88.9 b | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a |

| 500 | 0.0 e | 33.4 e | 53.0 d | 90.4 c | 90.7 b | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | |

| 1000 | 0.0 e | 54.8 d | 56.5 c | 100 a | 92.2 b | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | |

| 2000 | 58.0 e | 78.9 c | 66.4 d | 100 a | 93.9 b | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | |

| T. afroharzianum | 100 | 0.0 g | 63.3 e | 37.3 f | 82.2 d | 92.1 c | 97.3 b | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a |

| 500 | 0.0 f | 69.6 d | 54.2 e | 85.5 c | 92.9 b | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | |

| 1000 | 0.0 f | 82.0 d | 57.4 e | 87.8 c | 94.3 b | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | |

| 2000 | 88.6 c | 87.0 c | 73.4 d | 97.0 b | 95.5 b | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | |

| T. asperellum | 100 | 0.0 e | 0.0 e | 36.7 d | 43.7 c | 95.0 b | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a |

| 500 | 0.0 e | 0.0 e | 42.8 d | 78.3 c | 97.0 b | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | |

| 1000 | 36.2 f | 47.4 d | 45.9 e | 87.6 c | 97.8 b | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | |

| 2000 | 38.5 f | 73.7 d | 48.2 e | 92.2 c | 98.5 b | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | |

| T. asperelloides | 100 | 54.9 e | 58.0 c | 57.3 d | 23.2 f | 94.6 b | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a |

| 500 | 56.3 d | 58.7 c | 58.6 c | 100 a | 96.1 b | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | |

| 1000 | 58.1 e | 69.4 c | 62.0 d | 100 a | 97.1 b | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | |

| 2000 | 61.1 e | 80.0 c | 68.3 d | 100 a | 97.8 b | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | 100 a | |

zPro = Propineb, Tif =Thifluzamide, Man = Mancozeb, C+C = Carboxin+Captan, Flu = Fluazinam, TC = TCMTB, Prp= Propiconazole, Prc = Prochloraz, Tia = Thiabendazole and Tio =Tiophanate-methyl.

*The number in the rows expresses the mean percentage of growth inhibition in T. azevedoi, T. afroharzianum, T. asperellum and T. asperelloides for each one of the fungicides.

**Means with a common letter in the rows are not significantly different (P=0.05) according to Tukey´s procedure.

The mycelial growth of T. asperelloides was inhibited by the different concentrations of all fungicides. The fungicides Propineb, Thifluzamide (Figure 1 H) and Mancozeb reduced mycelial growth 54.9 to 80.0%. The mixture of Carboxin+Captan at a concentration of 100 ppm inhibited mycelial growth by 23.2%, but the same combination of fungicides at concentrations of 500, 1000 and 2000 ppm inhibited mycelial growth by 100% (Figure 1 I). Similar results were observed when the rest of the fungicides were used at the same concentrations, where the inhibition of the mycelial growth varied between 94.6 and 100 % (Table 7).

Discussion

In this study Thifluzamide had a greater in vitro effect on the mycelial growth of S. rolfsii, especially in the dose of 0.1 and 0.01 ppm in the five concentrations studied: despite the lack of any reference studies on the effect of this fungicide on the in vitro inhibition of the mycelial growth of the fungus, studies carried out in China indicated that the same fungicide has a preventative effect against soft rot in Dendrobium officinale (Yajun et al., 2018).

Likewise, Propineb inhibited the mycelial growth of the fungus by 41.1%, which coincides with previous studies in which the concentration of 100 ppm of this fungicide was used (Shirsole et al., 2019), and which inhibited 75.4% of the mycelial growth of

S. rolfsii obtained from chickpea (Cicer arietinum) in India. In turn, Vikram et al. (2023) evaluated the same molecule at 150 ppm, and it inhibited the mycelial growth of the fungus in wheat plants (Triticum spp.) in India by 17.7%, which contrasts with the results from this study. On the other hand, Mancozeb displayed an inhibition of 75.0% of the phytopathogen at a concentration of 100 ppm, which coincides with Shirsole et al. (2019), who found that this fungicide inhibited the growth of the fungus by 100% at the same concentration, whereas Vikram et al. (2023) found that the fungicide, at 50 and 150 ppm, inhibited they mycelial growth of the fungus by 57 and 100%, respectively. However, Das et al. (2014) reported an inhibition of 20% at 100 ppm, which contrasted with Chandra et al. (2020), who recorded that the same fungicide at 250 ppm inhibited 6.3% of the mycelial growth of the fungus from tomato plants in India. In this study, the Carboxin+Captan mixture completely inhibited S. rolfsii at concentrations of 10 and 100 ppm, which contrasted with the results by Das et al. (2014), who determined that Carboxin mixed with Tiram inhibited the growth of the fungus by 86.4 and 100%, respectively, at the same dose, which may be due to a synergy when combining both molecules.

Propiconazole exerted an inhibitory effect, comparable to the results by Das et al. (2014) who evaluated at 1, 10 and 100 ppm of this molecule, which inhibited the growth of S. rolfsii isolated from eggplant (Solanum melongena) in India by 27.2, 55.5 and respectively. Similar results were obtained by Prasad et al. (2017) in India, who found that this fungicide inhibited the mycelial growth of the fungus obtained from tomato plants by 100% at a concentration of 150 ppm. This contrasts with the results by Das et al. (2014), who indicated that the fungicide did not inhibit the mycelial growth of the pathogen at 1, 10 and 50 ppm, although it did inhibit (19.4%) at a concentration of 100 ppm, which coincides with the results of this study, in which the fungicide inhibited by 100% at a concentration of 100 ppm.

In relation to the production of sclerotia by S. rolfsii en PDA, Thifluzamide, Prochloraz, Propineb, Propiconazole, Carboxin+Captan and Mancozeb inhibited the formation of sclerotia in the concentration of 100 ppm, which contrasted with the fungicides of the group of Benzimidazoles (Thiabendazole and Thiophanate-methyl). These eariler studies indicate that Thiabendazole at a concentration of 4,000 inhibited the formation of S. rolfsii sclerotia obtained from onion (Allium cepa), chilli pepper (Capsicum annuum), tomato and barley (Hordeum vulgare) plants (Pérez-Moreno et al., 2009), which coincides with the results of this investigation, since the reduction in the formation of sclerotia was related with the increase in the concentrations of the fungicide. On the other hand, additional studies indicated that the in vitro evaluation of Mancozeb at 2,000 ppm reduced from 545 to 272 the S. rolfsii sclerotia obtained from eggplant plants in Bangladesh (Siddique et al., 2016). These results contrast with those obtained in this study, since at 100 ppm, the production of sclerotia was completely inhibited, indicating variability in the sensitivity of the fungus to this molecule. The results of this study suggest that Thifluzamide, Prochloraz, Propineb, Propiconazole, Carboxin+Captan and Mancozeb can reduce the in vitro production of sclerotia, indicating that these fungicides display potential for the reduction of these structures in the field.

The fungicides Propineb, Thifluzamide and Mancozeb displayed the lowest effect on mycelial growth in T. azevedoi, T. afroharzianum, T. asperellum and T. asperelloides, with a differential response of these species to the fungicides and their respective concentrations. In general, T. azevedoi and T. afroharzianum displayed the lowest inhibiting effect due to the different concentrations of Propineb. These results coincide with those by Manandhar et al. (2020), who, in Nepal, determined that T. harzianum and the isolation T22 in vitro at 100 ppm were not inhibited by Propineb, whereas T. asperellum, T. viride and the isolation T69 were inhibited by 13.1, 28.7 and 0.8%, respectively; these isolations were obtained from the rhizosphere of vegetable orchards in Nepal. These authors recorded that Mancozeb at 100 ppm inhibited T. harzianum, T. viride, T. asperellum, T22 and T69 by 10.8, 16.2, 28.3, 31.2 y 46.6%, respectively, which contrasts with findings by González et al. (2020), who recorded that Trichoderma reesei was not inhibited at 100 ppm.

In this study, Propiconazole inhibited the mycelial growth of the Trichoderma strains by 100% at a concentration of 100 ppm. By contrast, Zapata et al. (2023) found that, five days after the beginning of the study, the same fungicide at 1.25 mL L-1 inhibited the mycelial growth of T. koningiopsis by 31% (Tri-cotec® WG in Colombia). These authors recorded that Fluazinam inhibited by 39.6% at the dose of 1 mL L-1, which contrasts with the results of this study, since the mycelial growth inhibition of the four Trichoderma species varied between 88.9 and 98.5%. They also recorded that Prochloraz and Thiabendazole completely inhibited the mycelial growth, which also coincides with our results.

The difference in the sensitivity of S. rolfsii isolates and Trichoderma species to the different fungicides evaluated in this study, compared to other research studies, could be due to the constant use of fungicides in various crops. The exposure of this fungus to these products varies according to the agronomic management of the plant species, and over time, the fungus adapts to high doses of synthetic fungicides for disease management (Pérez-Moreno et al., 2009; Chaparro et al., 2011).

The results of this study open new lines of research related to studies of the effectiveness of fungicides at greenhouse and field levels. In this sense, the effectiveness of the molecules that were efficient in the in vitro inhibition of S. rolfsii must be determined. The most adequate phenological stage of the crop should also be evaluated, along with the concentration and the number of applications for the management of S. rolfsii, which causes the soft potato tuber rot, in the field.

The combination of the Trichoderma species with the fungicides Propineb and Thifluzamide and the in vitro effect of these against S. rolfsii is an option for the producer in the control of soft potato tuber rot. This approach has been practiced for the control of this disease in the potato crop (Rubayet and Bhuiyan, 2016). Future projects should lean towards the reduction in the concentration of fungicides when mixed with antagonistic Trichoderma species, with the aim of reducing environmental contamination, but particularly the contamination of tubers.

Conclusions

The results indicate that Thifluzamide (0.01 ppm) more efficiently inhibited the mycelial growth of S. rolfsii (32.7%) as compared to Propineb (12.2%). Both fungicides reduced sclerotia production by the pathogen (157-164 sclerotia/Petri dish), while the mean production of these resistance structures was 182 sclerotia per Petri dishes without fungicides. In Trichoderma spp., Propineb (100 ppm) only affected T. asperelloides (54.9% mycelial growth inhibition), whereas Thifluzamide showed variable effects (0- 63%), confirming its compatibility with Trichoderma species. These findings suggest that: 1) Thifluzamide is more effective against S. rolfsii but requires combination with other strategies to reduce sclerotia formation; 2) Both fungicides can be integrated with Trichoderma spp. in integrated management programs, as they show low toxicity toward Trichoderma spp.; 3) Fungicide selectivity varies according to Trichoderma isolate, highlighting the need for specific evaluations. It is recommended to optimize doses and formulations to improve S. rolfsii control without compromising biocontrol agents, prioritizing schemes that combine both approaches for sustainable management

Referencias

Arain, U., Dars, M., Ujjan, A., Bozdar, H., Rajput, A., Shahzad, S. 2022. Compatibility of myco-fungicide isolate (Trichoderma harzianumRifai) with fungicides and theirin-vitrosynergism assessment. Pakistan Journal of Phytophatology 34 147-155 10.33866/phytopathol.034.02.0763 https://doi.org/10.33866/phytopathol.034.02.0763 [ Links ]

Chaparro, A., Carvajal, L., Orduz, S. 2011. Fungicide tolerance ofTrichoderma asperelloidesandT. harzianumstrains. Agricultural Sciences 2 301-307 10.4236/as.2011.23040 https://doi.org/10.4236/as.2011.23040 [ Links ]

Chandra Sekhar, J., Jai Prakash Mishra, , Rajendra Prasad, , Vedukola Pulla Reddy, , Sunil Kumar, , Ankita Thakur, , Joginder, P. 2020. Isolation andin vitroevaluation of biocontrol agents, fungicides and essential oils against stem blight of tomato caused bySclerotium rolfsii(Curzi) C.C Tu and Kimber. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry 9 700-705 https://www.phytojournal.com/archives/2020/vol9issue3/PartK/9-3-28-316.pdf [ Links ]

Das, N. C., Dutta, B. K., Ray, D. C. 2014. Potential of some fungicides on the growth and development ofSclerotium rolfsiiSacc.in vitro. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications 4 1-5 http://www.ijsrp.org/research-paper-1214/ijsrp-p3624.pdf [ Links ]

Dinkwar, G., Yadav, V., Kumar, A., Nema, S., Mishra, S. 2023. Compatibility of fungicides with potentTrichodermaisolates. International Journal of Plant and Soil Science 35 1934-1948 10.9734/ijpss/2023/v35i183475 https://doi.org/10.9734/ijpss/2023/v35i183475 [ Links ]

FAO, Organización de la Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura 2022. FAOSTAT. www.fao.org/faostat/es/#data/QC/visualize https://www.fao.org/faostat/es/#data/QC/visualize [ Links ]

Ferreira, F., Herrmann, A., Calabrese, C., Bello, F., Vázquez, D., Musumeci, M. 2020. Effectiveness ofTrichodermastrains isolated from the rhizosphere of citrus tree to controlAlternaria alternata,Colletotrichum gloeosporioidesandPenicillium digitatumA21 resistant to pyrimethanil in post‐harvest oranges (Citrus sinensisL. (Osbeck)). Journal of Applied Microbiology 129 712-727 10.1111/jam.14657 https://doi.org/10.1111/jam.14657 [ Links ]

Gonzalez, M., Magdama, F., Galarza, L., Sosa, D., Romero, C. 2020. Evaluation of the sensitivity and synergistic effect ofTrichoderma reeseiand mancozeb to inhibit underin vitroconditions the growth ofFusarium oxysporum. Communicative and Integrative Biology 13 160-169 10.1080/19420889.2020.1829267 https://doi.org/10.1080/19420889.2020.1829267 [ Links ]

Kator, L., Zakki, Y., Ona, D. 2015. Sclerotium rolfsii; causative organism of southern blight, stem rot, white mold and sclerotia rot disease. Annals of Biological Research 6 78-89 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343268195_Sclerotium_rolfsii_Causative_organism_of_southern_blight_stem_rot_white_mold_and_sclerotia_rot_disease [ Links ]

Kim, S., Lee, Y., Balaraju, K., Jeon, Y. 2023. Evaluation ofTrichoderma atrovirideandTrichoderma longibrachiatumas biocontrol agents in controlling red pepper anthracnose in Korea. Frontiers in Plant Science 14 1-15 10.3389/fpls.2023.1201875 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2023.1201875 [ Links ]

Kumar, R., Ghatak, A., Bhagat, A. 2018. Assessing fungicides for seedling protection of cucumber to collar rot disease caused bySclerotium rolfsii. International Journal Plant Protection 11 10-17 10.15740/HAS/IJPP/11.1/10-17 https://doi.org/10.15740/HAS/IJPP/11.1/10-17 [ Links ]

Little, T. M., Hills, F. J. 1973. Agricultural Experimentation Design and Analysis. John Wiley and Sons 350 New York, USA [ Links ]

Manandhar, R., Timila, D., Karkee, S., Baidya, S. 2020. Compatibility study ofTrichodermaisolates with chemical fungicides. The Journal of Agriculture and Environment 21 9-18 https://moald.gov.np/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/The-Agriculture-and-Environment-VOL-21-2020-final.pdf#page=17 [ Links ]

Meena, P. N., Meena, A. K., Ram, C. 2023. Morphological and molecular diversity inSclerotium rolfsiiSacc., infecting groundnut (Arachis hypogaeaL.). Discover Agriculture 1 1-11 10.1007/s44279-023-00003-0 https://doi.org/10.1007/s44279-023-00003-0 [ Links ]

Paparu, P., Acur, A., Kato, F., Acam, C., Nakibuule, J., Nkuboye, A., Musoke, S., Mukankusi, C. 2020. Morphological and pathogenic characterization ofSclerotium rolfsii, the causal agent of southern blight disease on common bean in Uganda. Plant Disease 104 2130-2137 10.1094/PDIS-10-19-2144-RE https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-10-19-2144-RE [ Links ]

Pérez-Moreno, L., Villalpando-Mendiola, J. J., Castañeda-Cabrera, C., Ramírez-Malagón, R. 2009. Sensibilidadin vitrodeSclerotium rolfsiiSaccardo, a los fungicidas comúnmente usados para su combate. Revista Mexicana de Fitopatología 27 11-17 https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0185-33092009000100002 [ Links ]

Prasad, M., Sagar, B., Devi, G., Rao, S. 2017. In vitroevaluation of fungicides and biocontrol agents against damping off disease caused bySclerotium rolfsiion tomato. International Journal of Pure Applied Bioscience 5 1247-1257 10.18782/2320-7051.5144 https://doi.org/10.18782/2320-7051.5144 [ Links ]

Roca, L., Raya, M., Luque, F., Agustí, C., Romero, J., Trapero, A. 2016. First report ofSclerotium rolfsiicausing soft rot of potato tubers in Spain. Plant Disease 100 2535-2535 10.1094/PDIS-12-15-1505-PDN https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-12-15-1505-PDN [ Links ]

Rubayet, M. T., Bhuiyan, M. K. A. 2016. Integrated management of stem rot of potato caused bySclerotium rolfsii. Bangladesh Journal Plant Pathology 32 7-14 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328476753_INTEGRATED_MANAGEMENT_OF_STEM_ROT_OF_POTATO_CAUSED_BY_SCLEROTIUM_ROLFSII#fullTextFileContent [ Links ]

Shirsole, S. S., Khare, N., Lakpale, N., Kotasthane, A. S. 2019. Evaluation of fungicides againstSclerotium rolfsiiSacc. incitant of collar rot of chickpea. The Pharma Innovation Journal 8 310-316 https://www.thepharmajournal.com/archives/2019/vol8issue12/PartF/8-12-18-288.pdf [ Links ]

SIAP, Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera 2023. Sistema de Información Agroalimentaria. SIAPhttps://www.gob.mx/siap/documentos/siacon-ng-161430 [ Links ]

Siddique, M., Faruq, A., Mazumder, M., Khaiyam, M. O., Islam, M. 2016. Evaluation of Some Fungicides and Bio-Agents againstSclerotium rolfsiiand Foot and Root Rot Disease of Eggplant (Solanum melongenaL.). The Agriculturists 14 92 10.3329/agric.v14i1.29105 https://doi.org/10.3329/agric.v14i1.29105 [ Links ]

Singh, B., Bhardwaj, V., Kaur, K., Kukreja, S., Goutam, U. 2021. Potato periderm is the first layer of defense against biotic and abiotic stresses: a review. Potato Research 64 131-146 10.1007/s11540-020-09468-8 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11540-020-09468-8 [ Links ]

Torrance, L., Talianksy, M. 2020. Potato Virus Y emergence and evolution from the Andes of South America to become a major destructive pathogen of potato and other solanaceous crops worldwide. Viruses 12 1430 10.3390/v12121430 https://doi.org/10.3390/v12121430 [ Links ]

Vincent, J. M. 1947. Distortion of fungi hyphae in the presence of certain inhibitors. Nature 159 850 10.1038/159850b0 https://doi.org/10.1038/159850b0 [ Links ]

Vikram, , Kumar, S., Ashwarya, L., Patel, 2023. Efficacy of Various Fungicides and Herbicides for the Management of Wheat Foot Rot Disease. International Journal of Plant & Soil Science 35 1066-1073 https://adaswk3423.s3.ap-south-1.amazonaws.com/Vikram35192023IJPSS104517.pdf [ Links ]

Widmer, T. 2019. Compatibility ofTrichoderma asperellumisolates to selected soil fungicides. Crop Protection 120 91-96 10.1016/j.cropro.2019.02.017 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2019.02.017 [ Links ]

Yajun, H., Huiming, S., Pei, D., Lifeng, G., Yong, X., Hanrong, W. 2018. Efficacy evaluation of 16% validamycin thyfluzamide SC againstSclerotium rolfsiiinDendrobium officinaleKimura et migo. Plant Diseases and Pests 9 41-42 10.19579/j.cnki.plant-d.p.2018.01.010 https://doi.org/10.19579/j.cnki.plant-d.p.2018.01.010 [ Links ]

Yao, X., Guo, H., Zhang, K., Zhao, M., Ruan, J., Chen, J. 2023. Trichodermaand its role in biological control of plant fungal and nematode disease. Frontier in Microbiology 14 1-15 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1160551 https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1160551 [ Links ]

Yassin, M., Mostafa, F., Al-Askar, A. 2021. In vitroantagonistic activity ofTrichoderma harzianumandT. viridestrains compared to carbendazim fungicide against the fungal phytopathogens ofSorghum bicolor(L.) Moench. Egyptian Journal of Biological Pest Control 31 1-9 https://doi.org/10.1186/s41938-021-00463 [ Links ]

Zapata, Y., Botina, B. 2023. Efecto de coadyuvantes, fungicidas e insecticidas sobre el crecimiento deTrichoderma koningiopsisTh003. Revista Mexicana de Fitopatología 41 412-433 10.18781/r.mex.fit.2305-1 https://doi.org/10.18781/r.mex.fit.2305-1 [ Links ]

Received: May 30, 2024; Accepted: March 27, 2025

texto en

texto en