1. Introduction

The most comprehensive and long-term study to investigate chromospheric activity in

stars is the Mount Wilson HK project, which started in 1966 and continued for almost

40 years until 2003 (Wilson 1978; Vaughan et al. 1978; Duncan et al. 1991; Baliunas et

al. 1995). The HK project aimed to examine the chromospheric activity and

its change in stars by measuring the resonance doublet of singly ionized calcium (Ca

II H& K), which is a good indicator of chromospheric activity. From the

long-term Ca II H& K measurements, it was found that 60% of the observed stars

exhibited periodic and cyclical changes similar to the solar activity cycle (Baliunas et al. 1998). Donahue et al. (1996) applied period analysis to the 12-year HK

measurements of 37 main sequence stars observed within the scope of the HK project

and determined the largest (P

max) and the smallest (P

min) values of the observed photometric periods of each star. They also

calculated the ΔP = P

max − P

min values and the average photometric period of each star determined

over 12 years and adopted this value as the average rotation period (

Rechecking the results given in Özdarcan (2021) with a larger sample group will provide information about the reliability of the separation and enable the relationship between the rotation period and the SDR to be determined more reliably over a broader range of photometric periods. For this purpose, thirty-five stars that were determined to show chromospheric activity and have never been studied before, were selected. In the next section, we describe new observations and collected data of the target stars. In the third section, we estimate the astrophysical properties of the target stars from new U BV observations and determine seasonal photometric periods from long-term photometry to estimate the magnitude of the surface differential rotation. In the final section, we summarize our findings and give a comparison with theoretical predictions.

2. Data

2.1. Observations

We carry out Johnson U BV observations of the target stars with a 0.35m Schmidt-Cassegrain telescope equipped with Optec SSP-5 photometer located at Ege University Observatory Application and Research Center (EUOARC). The photometer includes an R6358 photomultiplier tube, which is sensitive to the longer wavelengths at the optical part of the electromagnetic spectrum. We use a circular diaphragm with an angular size of 53′′ and we adopt ten seconds of integration time for all observations. A typical observing sequence for a selected target is like sky-sky-VAR-VAR-VAR-VAR-sky-sky, where sky and VAR denote measurements from the sky and the variable star, respectively. We list the target stars in Table 1.

TABLE 1 LIST OF TARGET STARS

| Target Star |

|

|

|

|

|

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TYC 05275-00646-1 | IM Cet | 01 01 45.3 | −12 08 02.4 | 9.67 | 1.042 | 3 |

| TYC 04688-02015-1 | IR Cet | 01 46 51.7 | −05 47 15.1 | 11.29 | 1.37 | 7 |

| TYC 05282-02210-1 | IZ Cet | 02 19 47.3 | −10 25 40.6 | 10.72 | 1.076 | 2 |

| TYC 00648-01252-1 | HW Cet | 03 12 34.2 | +09 44 57.1 | 10.39 | 1.089 | 1 |

| TYC 04723-00878-1 | LN Eri | 03 48 36.2 | −05 20 30.4 | 11.713 | 0.971 | 5 |

| TYC 04734-00020-1 | OP Eri | 04 36 12.5 | −01 50 24.9 | 10.17 | 0.961 | 7 |

| TYC 00083-00788-1 | V1330 Tau | 04 42 18.5 | +01 17 39.8 | 11.88 | 1.042 | 1 |

| V1339 Tau | V1339 Tau | 04 48 57.9 | +19 14 56.1 | 11.8 | 1.141 | 1 |

| TYC 01281-01672-1 | V1841 Ori | 05 00 49.2 | +15 27 00.6 | 10.83 | 1.218 | 1 |

| TYC 00099-00166-1 | V1854 Ori | 05 13 19.0 | +01 34 47.0 | 10.28 | 0.907 | 1 |

| TYC 04767-00071-1 | V2814 Ori | 05 39 45.6 | −00 55 51.0 | 11.33 | 1.212 | 7 |

| GSC 00140-01925 | V2826 Ori | 06 15 18.6 | +03 47 01.0 | 11.64 | 1.483 | 7 |

| TYC 04806-03158-1 | V969 Mon | 06 36 56.3 | −05 21 03.6 | 11.71 | 0.66 | 2 |

| TYC 01358-01303-1 | V424 Gem | 07 16 50.4 | +21 45 00.1 | 10 | 1.074 | 1 |

| TYC 01942-00318-1 | KU Cnc | 08 35 26.8 | +24 15 39.4 | 11.48 | 1.201 | 1 |

| TYC 00840-00219-1 | EQ Leo | 10 13 23.8 | +12 08 45.7 | 9.345 | 1.091 | 1 |

| TYC 00845-00981-1 | IN Leo | 10 39 59.0 | +13 27 22.0 | 10.326 | 0.901 | 1 |

| TYC 00856-01223-1 | OS Leo | 11 33 36.9 | +07 51 28.9 | 11.369 | 1.344 | 6 |

| TYC 00865-01164-1 | V358 Vir | 11 56 51.6 | +08 27 21.3 | 11.37 | 1.347 | 1 |

| TYC 00881-00657-1 | PW Com | 12 35 57.4 | +13 29 25.2 | 10.27 | 1.044 | 2 |

| TYC 05003-00309-1 | V436 Ser | 15 23 46.1 | −00 44 24.7 | 11.13 | 1.214 | 1 |

| TYC 05003-00138-1 | V561 Ser | 15 26 52.7 | −00 53 11.7 | 11.39 | 1.201 | 7 |

| TYC 05610-00066-1 | V354 Lib | 15 54 44.9 | −07 52 04.5 | 11.34 | 1.229 | 1 |

| V1330 Sco | V1330 Sco | 16 23 07.8 | −23 00 59.9 | 11.85 | 1.263 | 1 |

| TYC 05050-00802-1 | V2700 Oph | 16 51 22.1 | −00 50 01.2 | 11.7 | 1.007 | 5 |

| TYC 00990-02029-1 | V1404 Her | 17 16 29.7 | +13 23 14.5 | 11.41 | 0.758 | 7 |

| GSC 00978-01306 | V2723 Oph | 17 17 11.4 | +08 15 24.6 | 12 | 1 | 4 |

| TYC 01572-00794-1 | V1445 Her | 18 16 52.7 | +17 57 03.1 | 11.22 | 0.726 | 7 |

| TYC 01062-01972-1 | V1848 Aql | 19 54 03.1 | +10 41 45.4 | 10.16 | 0.965 | 6 |

| TYC 05165-00365-1 | V1890 Aql | 20 11 39.5 | −02 35 25.7 | 11.15 | 0.975 | 7 |

| TYC 05183-00044-1 | V365 Aqr | 20 54 09.2 | −02 45 33.7 | 10.74 | 0.964 | 7 |

| GSC 00563-00384 | V641 Peg | 22 28 36.1 | +03 05 25.6 | 11.89 | 1.165 | 7 |

| TYC 02221-00759-1 | V543 Peg | 22 47 22.7 | +23 13 16.6 | 11.48 | 1.197 | 7 |

| TYC 01712-00736-1 | V580 Peg | 23 12 29.0 | +17 09 21.7 | 11.107 | 1.467 | 1 |

| TYC 00583-00566-1 | KZ Psc | 23 16 45.0 | +06 18 57.4 | 10.77 | 1.027 | 7 |

References are 1: Berdnikov & Pastukhova (2008), 2: Bernhard & Otero (2011), 3: Bernhard et al. (2009), 4: Bernhard Lloyd (2008b), 5: Bernhard & Lloyd (2008a), 6: Bernhard et al. (2010), 7: Schirmer et al. (2009). V and B − V magnitudes are from Tycho catalogue (Høg et al. 2000).

We follow the procedure described in Hardie (1964) to obtain reduced instrumental magnitudes. Moreover, we observe a set of standard stars selected from Landolt (2009) and Landolt (2013) along with each target. Hence, we transform all reduced instrumental magnitudes of the target stars into the standard system. Since RA coordinates of the target stars are distributed homogeneously around the celestial equator, we carried out standard star observations on two nights with an almost six-month time difference. These are 27th December 2022 and 13th July 2023 nights. We give computed transformation coefficients in the Appendix section.

Preliminary analysis of the EUOARC observations shows that signal-to-noise ratios of TYC 5275-00646-1, V1330 Sco, TYC 5610-00066-1, TYC 5050-00802-1, TYC 01572-00794-1 and GSC 00140-01925 are not sufficient for reliable colour and magnitude measurements. Increasing the integration time or gain, or using another EUOARC telescope (0.4m Schmidt-Cassegrain with a CCD camera and standard Johnson-Bessell filters) does not change the situation. Therefore, we take B − V colours and V magnitudes of these stars from The AAVSO Photometric All-Sky Survey for analysis (APASS; Henden et al. 2015). We tabulate standard colours and magnitudes of the target systems in Table 2.

TABLE 2 JOHNSON UBV STANDARD MAGNITUDES AND COLOURS OF THE TARGET SYSTEMS

| Star |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IM Cet * | 10.38 | 0.05 | 1.10 | 0.10 | - | - | 0.0275 | 1.16 |

| IR Cet | 11.39 | 0.06 | 1.09 | 0.09 | 0.54 | 0.29 | 0.0228 | 1.16 |

| IZ Cet | 10.25 | 0.06 | 1.01 | 0.06 | 0.77 | 0.19 | 0.0242 | 1.08 |

| HW Cet | 10.77 | 0.05 | 0.99 | 0.02 | 0.81 | 0.15 | 0.3132 | 0.77 |

| LN Eri | 11.79 | 0.05 | 1.02 | 0.05 | −0.06 | 0.13 | 0.0787 | 1.03 |

| OP Eri | 10.13 | 0.06 | 1.05 | 0.04 | 0.58 | 0.14 | 0.0422 | 1.10 |

| V1330 Tau | 11.71 | 0.06 | 1.16 | 0.13 | 0.51 | 0.20 | 0.1144 | 1.14 |

| V1339 Tau | 11.99 | 0.07 | 1.02 | 0.07 | 1.11 | 0.30 | 0.4134 | 0.70 |

| V1841 Ori | 11.06 | 0.06 | 1.24 | 0.04 | 1.19 | 0.45 | 0.3542 | 0.98 |

| V1854 Ori | 10.37 | 0.05 | 0.92 | 0.04 | 0.27 | 0.16 | 0.1111 | 0.90 |

| V2814 Ori | 11.19 | 0.08 | 1.52 | 0.07 | 1.81 | 0.17 | 0.3338 | 1.28 |

| V2826 Ori * | 11.64 | 0.05 | 1.48 | 0.08 | - | - | 0.6493 | 0.92 |

| V969 Mon | 11.53 | 0.08 | 1.37 | 0.09 | 1.03 | 0.39 | 0.3963 | 1.06 |

| V424 Gem | 10.38 | 0.06 | 1.19 | 0.02 | 1.08 | 0.18 | 0.0559 | 1.22 |

| KU Cnc | 11.59 | 0.11 | 1.38 | 0.11 | 1.96 | 0.38 | 0.0276 | 1.44 |

| EQ Leo | 9.56 | 0.06 | 1.19 | 0.03 | 0.79 | 0.17 | 0.0326 | 1.25 |

| IN Leo | 10.55 | 0.06 | 1.01 | 0.07 | 0.41 | 0.17 | 0.0339 | 1.07 |

| OS Leo | 11.71 | 0.06 | 0.98 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.19 | 0.0380 | 1.03 |

| V358 Vir | 11.58 | 0.06 | 1.00 | 0.04 | 0.73 | 0.35 | 0.0165 | 1.07 |

| PW Com | 10.55 | 0.05 | 0.79 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.0308 | 0.85 |

| V436 Ser | 11.32 | 0.15 | 1.12 | 0.19 | 0.53 | 0.61 | 0.0485 | 1.16 |

| V561 Ser | 11.35 | 0.16 | 1.17 | 0.19 | 0.57 | 0.48 | 0.0557 | 1.20 |

| V354 Lib * | 11.38 | 0.06 | 1.16 | 0.10 | - | - | 0.1607 | 1.09 |

| V1330 Sco * | 11.85 | 0.04 | 1.26 | 0.07 | - | - | 1.8802 | 1.35 |

| V2700 Oph * | 11.72 | 0.17 | 1.28 | 0.22 | - | - | 0.1014 | 1.27 |

| V1404 Her | 11.78 | 0.20 | 0.91 | 0.25 | 0.64 | 0.31 | 0.1403 | 0.86 |

| V2723 Oph | 12.24 | 0.20 | 1.10 | 0.28 | 0.32 | 0.29 | 0.1047 | 1.09 |

| V1445 Her * | 11.18 | 0.12 | 0.98 | 0.15 | - | - | 0.1865 | 0.88 |

| V1848 Aql | 10.07 | 0.10 | 0.97 | 0.08 | 0.35 | 0.24 | 0.2900 | 0.77 |

| V1890 Aql | 11.17 | 0.12 | 1.26 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.27 | 0.1631 | 1.19 |

| V365 Aqr | 10.91 | 0.23 | 0.82 | 0.26 | 0.83 | 0.34 | 0.0783 | 0.83 |

| V641 Peg | 11.69 | 0.08 | 1.07 | 0.14 | −0.15 | 0.23 | 0.0824 | 1.08 |

| V543 Peg | 11.38 | 0.07 | 0.88 | 0.14 | 0.67 | 0.36 | 0.0847 | 0.89 |

| V580 Peg | 11.05 | 0.08 | 1.27 | 0.12 | 0.91 | 0.25 | 0.1112 | 1.25 |

| KZ Psc | 10.59 | 0.09 | 1.17 | 0.14 | 0.48 | 0.23 | 0.0773 | 1.18 |

Note: V and B − V measurements of the target stars (marked by * sign) are from Henden et al. (2015). These targets do not have reliable U measurement. In the last two columns, we list the estimated interstellar reddening values and corrected B − V colour indexes. See text for the details.

2.2. Long-Term Photometry

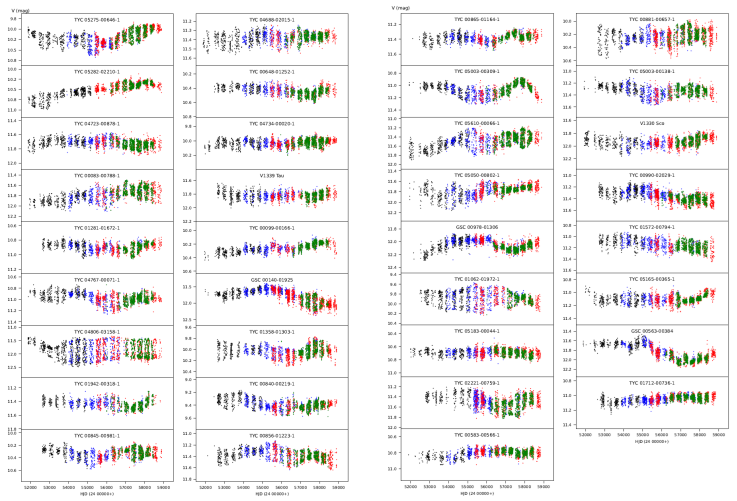

Besides EUOARC observations, we collect long-term V photometry of target stars from The All Sky Automated Survey (ASAS, Pojmanski 1997, 2002; Pojmanski et al. 2005) and All-Sky Automated Survey for Supernovae Sky Patrol (ASAS-SN, Shappee et al. 2014; Kochanek et al. 2017). The time range of the collected data usually spans over 15 or 18 years, depending on the beginning and the end of the observations. However, there is a significant time gap (3 or 4 years) between ASAS and ASAS-SN data, where no observation is available. This prevents us from precise tracing of the long-term photometric behaviour of our target systems. These time gaps are filled with unpublished observations obtained in the scope of the extension of the ASAS project (ASAS3-N and ASAS4; Pojmanski, 2022; priv. comm.). Therefore, we are able to collect photometric data of the target stars without a significant time gap. We plot the collected data of each target in Figure 1.

3. Analysis

3.1. Photometric Properties

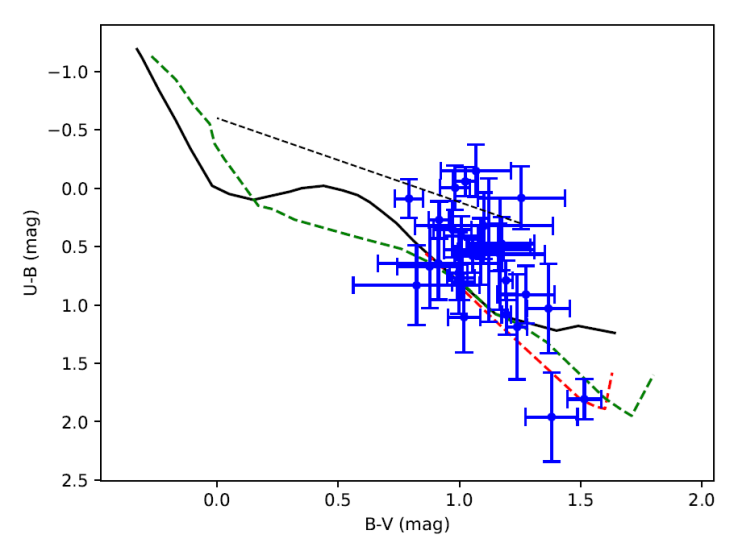

In the first step of our analysis, we plot measured standard U −

B and B − V colours of

the target systems in a colour - colour diagram (Figure 2). More than half of the target stars appear systematically

shifted from the predicted positions of the unreddened main sequence stars. This

could be interpreted as the effect of interstellar reddening, which means a kind

of systematic interstellar reddening is valid for most of our target stars.

However, these stars are located at different positions in the celestial sphere.

If one applied a reddening correction suggested by Figure 2, then many of the target stars would become early-type

stars. This is contradictory to the reported properties of our target stars,

such as detected X-ray emission, photometric colours and light curve properties

(see references mentioned in Table 1). In

this case, interstellar reddening cannot be a satisfactory explanation for the

disagreement between observed and predicted colours seen in Figure 2. An alternative explanation is colour excess due to

the chromospheric activity of the target stars. Since their chromospheric

activity was confirmed by their properties in the references mentioned above, we

may expect average colour excesses of

Fig. 2 Positions of the target systems on the U BV colour - colour diagram. Six targets that do not have reliable measurements are not plotted in the figure. The continuous curve (black) shows the theoretically expected positions of the unreddened main sequence stars, while the dashed curves show the positions of unreddened giant (shorter curve) and supergiant stars (longer curve), respectively. The dashed (black) line denotes the reddening vector. Theoretical data are from Drilling & Landolt (2000). The colour figure can be viewed online.

3.2. Astrophysical Properties

By using the corrected B −V colours, we first

determine the effective temperatures (T

ef f

) and bolometric corrections (BC) of the target stars according to the

empirical colour - temperature and colour - bolometric correction relations

given in Gray (2005). Then, we determine

the distance of each target depending on its parallax measurement taken from the

third GAIA data release (Gaia Collaboration et

al. 2016, 2023). In the third

step, we use the measured magnitudes (in Table

2) and the calculated distances (d) of each target

in the distance modulus formula and find the absolute V magnitude

(M

V

). After that, we apply estimated bolometric corrections to the

calculated MV magnitudes and obtain the bolometric absolute magnitude

(M

bol

) of each star. In the final step, we use the calculated

M

bol

of each star with the solar M

bol

value of

TABLE 3 ESTIMATED ASTROPHYSICAL PROPERTIES OF THE TARGET STARS

| Star |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

L/L ⊙ |

|

Sp. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IM Cet | 4602 | 161 | -0.495 | 427 | 7 | 2.14 | 0.19 | 1.65 | 0.10 | 17 | 1 | K2 III |

| IR Cet | 4610 | 150 | -0.492 | 379 | 2 | 3.43 | 0.10 | 2.93 | 0.06 | 5.3 | 0.3 | K2 III |

| IZ Cet | 4752 | 99 | -0.430 | 341 | 3 | 2.51 | 0.10 | 2.08 | 0.05 | 11.6 | 0.5 | K1 III |

| HW Cet | 5415 | 41 | -0.149 | 57.4 | 0.1 | 6.00 | 0.05 | 5.86 | 0.07 | 0.36 | 0.01 | G9 V |

| LN Eri | 4834 | 91 | -0.391 | 167 | 4 | 5.43 | 0.31 | 5.04 | 0.15 | 0.76 | 0.09 | K0 IV |

| OP Eri | 4713 | 75 | -0.448 | 486.62 | 0.09 | 1.56 | 0.06 | 1.11 | 0.03 | 28.2 | 0.8 | K1 III |

| V1330 Tau | 4647 | 212 | -0.477 | 403 | 14 | 3.33 | 0.41 | 2.85 | 0.23 | 5.7 | 0.9 | K1 III |

| V1339 Tau | 5608 | 116 | -0.103 | 468 | 5 | 2.36 | 0.14 | 2.25 | 0.07 | 9.9 | 0.3 | G1 IV |

| V1841 Ori | 4941 | 63 | -0.339 | 53.09 | 0.04 | 6.34 | 0.06 | 6.00 | 0.08 | 0.31 | 0.01 | K3 V |

| V1854 Ori | 5101 | 81 | -0.264 | 76.3 | 0.8 | 5.61 | 0.13 | 5.35 | 0.08 | 0.57 | 0.03 | K2 V |

| V2814 Ori | 4417 | 106 | -0.563 | 483 | 5 | 1.74 | 0.14 | 1.17 | 0.23 | 27 | 6 | K3 III |

| V2826 Ori | 5054 | 118 | -0.285 | 561 | 1 | 0.88 | 0.06 | 0.60 | 0.08 | 45 | 1 | G6 III |

| V969 Mon | 4774 | 133 | -0.420 | 412 | 3 | 2.23 | 0.11 | 1.81 | 0.10 | 14.9 | 0.6 | K0 III |

| V424 Gem | 4500 | 30 | -0.533 | 482 | 2 | 1.79 | 0.07 | 1.26 | 0.04 | 24.7 | 0.9 | K2 III |

| KU Cnc | 4163 | 162 | -0.760 | 41.27 | 0.03 | 8.43 | 0.11 | 7.67 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.01 | M1 V |

| EQ Leo | 4463 | 44 | -0.546 | 504 | 3 | 0.95 | 0.09 | 0.40 | 0.05 | 54 | 2 | K3 III |

| IN Leo | 4769 | 124 | -0.422 | 234 | 6 | 3.60 | 0.31 | 3.18 | 0.14 | 4.2 | 0.5 | K1 III |

| OS Leo | 4832 | 112 | -0.392 | 298 | 2 | 4.22 | 0.09 | 3.83 | 0.06 | 2.3 | 0.1 | K0 IV |

| V358 Vir | 4756 | 66 | -0.429 | 87.2 | 0.2 | 6.83 | 0.06 | 6.40 | 0.07 | 0.22 | 0.01 | K4 V |

| PW Com | 5213 | 132 | -0.217 | 206 | 1 | 3.89 | 0.09 | 3.67 | 0.05 | 2.7 | 0.1 | G4 IV |

| V436 Ser | 4603 | 307 | -0.495 | 326.9 | 0.4 | 3.60 | 0.15 | 3.10 | 0.09 | 4.5 | 0.3 | K2 III |

| V561 Ser | 4532 | 299 | -0.521 | 262 | 2 | 4.09 | 0.18 | 3.56 | 0.11 | 3.0 | 0.3 | K2 III |

| V354 Lib | 4728 | 155 | -0.442 | 250.1 | 0.4 | 3.89 | 0.07 | 3.45 | 0.06 | 3.3 | 0.1 | K1 III |

| V1330 Sco | 4303 | 101 | -0.619 | 138 | 4 | 6.15 | 0.31 | 5.53 | 0.20 | 0.48 | 0.09 | K4 IV |

| V2700 Oph | 4429 | 342 | -0.559 | 313 | 1 | 3.93 | 0.17 | 3.37 | 0.12 | 3.5 | 0.3 | K3 III |

| V1404 Her | 5188 | 497 | -0.227 | 480 | 2 | 2.94 | 0.20 | 2.71 | 0.08 | 6.5 | 0.4 | G4 IV |

| V2723 Oph | 4735 | 485 | -0.438 | 449 | 4 | 3.65 | 0.22 | 3.22 | 0.12 | 4.1 | 0.4 | K1 III |

| V1445 Her | 5135 | 276 | -0.249 | 337 | 2 | 2.96 | 0.13 | 2.71 | 0.07 | 6.5 | 0.3 | G5 IV |

| V1848 Aql | 5407 | 141 | -0.151 | 425 | 5 | 1.03 | 0.16 | 0.88 | 0.07 | 35 | 1 | G2 III |

| V1890 Aql | 4561 | 280 | -0.511 | 967 | 4 | 0.74 | 0.13 | 0.23 | 0.08 | 64 | 3 | K2 III |

| V365 Aqr | 5254 | 580 | -0.202 | 353 | 18 | 2.93 | 0.63 | 2.73 | 0.18 | 6.4 | 0.9 | G4 IV |

| V641 Peg | 4749 | 245 | -0.432 | 847 | 2 | 1.80 | 0.08 | 1.36 | 0.05 | 22.4 | 0.8 | K1 III |

| V543 Peg | 5131 | 274 | -0.251 | 597 | 8 | 2.24 | 0.16 | 1.99 | 0.06 | 12.6 | 0.6 | G5 III |

| V580 Peg | 4461 | 180 | -0.547 | 46 | 6 | 7.39 | 1.53 | 6.84 | 0.97 | 0.1 | 0.1 | K6 V |

| KZ Psc | 4568 | 215 | -0.508 | 278.22 | 0.05 | 3.13 | 0.09 | 2.62 | 0.06 | 7.0 | 0.3 | K2 III |

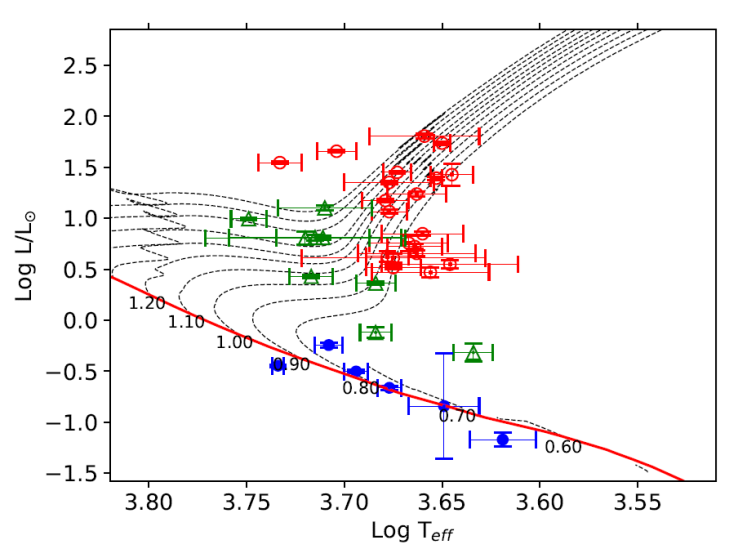

Now, we are in a position to determine the location of each target on the

Hertzsprung - Russell (HR) diagram (Figure

3). In the figure, one may notice that there is no available

evolutionary track for the positions of a few targets located at the redder part

of the diagram. These targets may be premain sequence stars, which still evolve

towards the zero-age main sequence. LN Eri, V1330 Sco, V2700 Oph and KZ Psc

might be premain sequence stars with their remarkably short photometric periods

(P < 8 day) and a light curve amplitude between

Fig. 3 Positions of the target systems on the HR diagram. Theoretical evolutionary tracks (dashed lines) for solar abundance (Y = 0.279 and Z = 0.017) are from Bressan et al. (2012). Each track is labelled with its corresponding mass in solar units. Continuous (red) curve denotes the zero-age main sequence. Filled (blue) circles are for main sequence stars, open triangles (green) denote sub-giant stars and open (red) circles show giant stars. The colour figure can be viewed online.

3.3. Analysis of Seasonal Light Curves

We use long-term photometry of each star (Figure 1) to determine seasonal light curve properties, which are photometric period (P phot ), peak-to-peak light curve amplitude (A) and minimum (V min ), maximum (V max ) and mean (V mean ) brightnesses. For that purpose, we first divide the photometric data of a given target into subsets, where each one covers an observing season. Then, we check each season by eye for any dramatic change in light curve amplitudes. If there is a significant amplitude change in a season, we further divide the corresponding subset into parts so that each part possesses a fairly constant amplitude.

Among photometric period determination methods, we employ Analysis of Variance (ANOVA, Schwarzenberg-Czerny 1996), which is a hybrid method that combines the power of Fourier analysis and ANOVA statistics. The method is capable of determining the best-fitting period for a given light curve independently of the shape of the light curve and is very effective to damp the amplitudes of the alias periods2. To estimate the uncertainty of the computed photometric periods, we follow the method proposed by Schwarzenberg-Czerny (1991). The method provides more accurate uncertainties compared to the least-squares correlation matrix or Rayleigh resolution criteria.

Before proceeding with the ANOVA method, we apply a linear fit to the corresponding subset light curve to remove any long-term brightness variation, because such a variation may alter the photometric period artificially. After the linear correction, we apply the ANOVA method to the residuals from the linear fit and determine the best-fitting period and the light curve properties mentioned above. After we find the final photometric period for a given subset, we make a phase-folded light curve of this subset concerning the final photometric period and fit a cubic spline polynomial to the phase-folded data. Here, the purpose is to determine the minimum and the maximum values of the spline function, which correspond to the brightnesses of the light curve maximum and minimum, respectively. The amplitude and the mean brightness can be calculated straight-forwardly from these values. Otherwise, fitted spline polynomials do not have any physical meaning. We list the analysis results in the Appendix (Table 5).

3.4. Photometric Periods and Surface Differential Rotation

In this section, we use the advantage of having long-term photometry to estimate the magnitude of the SDR. It is clear that determining the latitude of the cool surface spots from photometry is a well-known ill-posed problem. This prevents the type of differential rotation (solar type or anti-solar type) from being clearly determined in this study. However, the range in which the photometric period takes value for a particular star can set a lower limit for the magnitude of the SDR. Given the brief discussion above, we implicitly assume that all target stars possess solar-type SDR (i.e., the equator rotates faster than the poles). Therefore, we consider the observed minimum value of the photometric period as the equatorial rotation period. The observed maximum value, then, corresponds to the highest latitude at which spots could emerge during the time interval of the photometric data. We make a quantitative estimation of the magnitude of the SDR by relative shear defined in terms of periods (Equation 1),

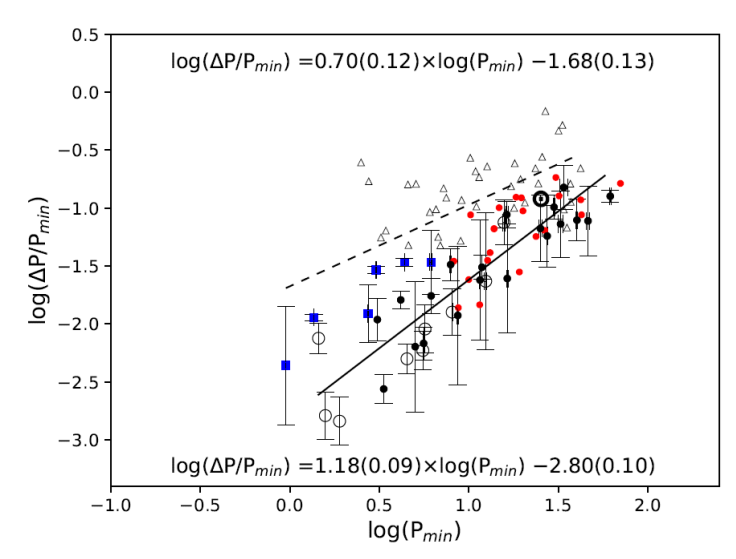

We take P max and P min values of each target star from Table 5 and compute the relative shear via Equation 1. We plot the P min - relative shear pair of each star in Figure 4. We also tabulate these pairs along with the estimated spectral types in Table 4.

Fig. 4 Relation between the observed minimum period P min and the calculated relative shear. Black filled circles show giant stars listed in Table 5, while blue filled square and open circle symbols denote main sequence stars and sub-giant stars, respectively. Open triangles show stars taken from Donahue et al. (1996), small (red) dots (without error bars) show RS CVn stars analysed in Özdarcan (2021) and five other stars mentioned in the text. We also show the position of our Sun in the figure. Dashed and straight lines show linear fits to the distribution of main sequence and giant stars, respectively. The corresponding coefficients and their statistical errors are given inside the plot window (upper one for the main sequence stars, lower one for the giant stars). The colour figure can be viewed online.

TABLE 4 CALCULATED PERIODS AND RELATIVE SHEAR VALUES OF THE TARGET STARS ALONG WITH THEIR SPECTRAL TYPES

| Star | Sp. |

|

|

|

|

ΔP/P min |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IM Cet | K2 III | 27.4 | 0.2 | 29.0 | 0.7 | 0.06 | 0.03 |

| IR Cet | K2 III | 16.3 | 0.3 | 17.7 | 0.2 | 0.09 | 0.02 |

| IZ Cet | K1 III | 7.92 | 0.06 | 8.18 | 0.04 | 0.032 | 0.009 |

| HW Cet | G9 V | 6.15 | 0.09 | 6.36 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| LN Eri | K0 IV | 1.4467 | 0.0009 | 1.458 | 0.003 | 0.008 | 0.002 |

| OP Eri | K1 III | 46.4 | 0.8 | 50 | 2 | 0.08 | 0.04 |

| V1330 Tau | K1 III | 8.68 | 0.08 | 8.787 | 0.005 | 0.012 | 0.009 |

| V1339 Tau | G1 IV | 15.7 | 0.2 | 16.9 | 0.4 | 0.08 | 0.03 |

| V1841 Ori | K3 V | 2.743 | 0.009 | 2.78 | 0.01 | 0.012 | 0.005 |

| V1854 Ori | K2 V | 1.3609 | 0.0007 | 1.3764 | 0.0006 | 0.0113 | 0.0007 |

| V2814 Ori | K3 III | 61.8 | 0.7 | 69.6 | 0.5 | 0.13 | 0.01 |

| V2826 Ori | G6 III | 25.2 | 0.5 | 26.8 | 0.6 | 0.07 | 0.03 |

| V969 Mon | K0 III | 5.018 | 0.006 | 5.05 | 0.02 | 0.006 | 0.005 |

| V424 Gem | K2 III | 40.2 | 0.4 | 43 | 1 | 0.08 | 0.03 |

| KU Cnc | M1 V | 0.950 | 0.001 | 0.954 | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.006 |

| EQ Leo | K3 III | 33 | 1 | 35.0 | 0.5 | 0.07 | 0.04 |

| IN Leo | K1 III | 6.161 | 0.009 | 6.27 | 0.03 | 0.017 | 0.005 |

| OS Leo | K0 IV | 5.69 | 0.01 | 5.74 | 0.01 | 0.009 | 0.003 |

| V358 Vir | K4 V | 4.376 | 0.007 | 4.525 | 0.009 | 0.034 | 0.002 |

| PW Com | G4 IV | 4.514 | 0.004 | 4.537 | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.001 |

| V436 Ser | K2 III | 11.55 | 0.06 | 11.8 | 0.4 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| V561 Ser | K2 III | 11.86 | 0.01 | 12.22 | 0.08 | 0.031 | 0.007 |

| V354 Lib | K1 III | 5.594 | 0.002 | 5.63 | 0.01 | 0.007 | 0.002 |

| V1330 Sco | K4 IV | 8.08 | 0.04 | 8.18 | 0.01 | 0.013 | 0.005 |

| V2700 Oph | K3 III | 3.347 | 0.002 | 3.356 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.001 |

| V1404 Her | G4 IV | 12.4 | 0.2 | 12.72 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| V2723 Oph | K1 III | 3.08 | 0.01 | 3.116 | 0.003 | 0.011 | 0.004 |

| V1445 Her | G5 IV | 1.896 | 0.001 | 1.8986 | 0.0002 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| V1848 Aql | G2 III | 16.4 | 0.2 | 16.8 | 0.2 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| V1890 Aql | K2 III | 34 | 2 | 39.1 | 0.5 | 0.15 | 0.05 |

| V365 Aqr | G4 IV | 1.5789 | 0.0004 | 1.5814 | 0.0009 | 0.002 | 0.001 |

| V641 Peg | K1 III | 30.0 | 0.3 | 33.0 | 0.5 | 0.10 | 0.02 |

| V543 Peg | G5 III | 5.538 | 0.005 | 5.571 | 0.009 | 0.006 | 0.002 |

| V580 Peg | K6 V | 3.030 | 0.006 | 3.119 | 0.003 | 0.029 | 0.002 |

| KZ Psc | K2 III | 4.168 | 0.009 | 4.235 | 0.006 | 0.016 | 0.003 |

For comparison, we also show the positions of the 37 main sequence stars analysed in Donahue et al. (1996) and 21 giant stars analysed in Özdarcan (2021). Five more giant stars are also plotted in the figure (with red dots), which are HD 208472 (Özdarcan et al. 2010), FG UMa (HD 89546, Ozdarcan et al. 2012) and BD+13 50000, TYC 5163-1764-1 and BD+11 3024 (Özdarcan & Dal 2018). We note that analysis of all these stars was done in a similar way as described above. The only difference could be that Donahue et al. (1996) used the S index based on Ca II H& K measurements, which is a spectroscopic indicator of the chromospheric activity. For the remaining stars, pure V photometry, which is a photometric indicator of the same phenomenon, was used.

A linear fit to the positions of all main sequence stars plotted in Figure 4 gives the coefficients shown in the upper part of the figure with a correlation coefficient of 0.67 and a p value of 6.9 × 10−7. In the figure, sub-giants and giants appear as aligned on the same slope. Thus, we apply a similar linear fit to the positions of all giant and sub-giant stars. The fit results in the coefficients shown in the bottom part of the figure with a correlation coefficient of 0.88 and a p value of 3.2 × 10−19.

4. Summary and discussion

Johnson U BV photometry of 35 target stars suggests a significant colour excess, particularly in the U − B colour, for most of the targets. We interpret this excess as the effect of intense chromospheric activity in the U BV colours. Neglecting the inter-stellar reddening, adopting average B − V colour excess reported in Amado (2003) and using GAIA parallaxes, we estimate astrophysical properties of the target stars via colour-temperature calibrations. At that point, we stress that we remove an average excess value from our observations, which apparently reduces the reliability of the estimated astrophysical properties. Therefore, we believe that a re-determination of colour excesses in U − B and B − V colours with a more comprehensive study based on a larger sample size deserves effort. In the current case, the positions of the target stars on the HR diagram indicate that six of our target stars are main-sequence star, while nine of them appear as sub-giant, and the remaining 20 stars are located in the region of giant stars.

Analysis of long-term V photometry of the target stars enables us to investigate possible variability of the photometric period, which indicates SDR. We determine seasonal photometric periods of each star and calculate the relative shear via observed minimum and maximum photometric periods in the time span of the available photometric data. However, among stars which we classify as giant, we find very short rotation periods. V2723 Oph, V2700 Oph, KZ Psc and V969 Mon are such stars. Since these stars appear in giant region on the HR diagram and giant stars often tend to have much longer periods, finding such short periods is not expected. One possible explanation is that these stars are likely members of a binary system. IZ Cet and V1330 Tau are such stars among our sample, which are reported as SB2 binaries (Torres et al. 2002). On the other hand, we carried out a quick inspection of space photometry provided by the T ESS satellite (Ricker et al. 2014) and did not notice any eclipse event for any star in our sample. Unfortunately, we have no high-resolution spectra to check if these stars exhibit an orbital motion in their radial velocities. Another possible explanation is that, if these giants are single, then they might be FK Com variables. These systems deserve additional attention by further spectroscopic studies.

Computing photometric periods and relative shear values for each star enables us to investigate the relation between the photometric period and the relative shear (i.e., differential rotation, Figure 4) via a more extended sample compared to Özdarcan (2021). In the figure, the distribution of the main sequence and giant stars shows a significant distinction in the shorter periods, while the distinction tends to disappear towards long periods. The slopes of the best-fitting linear fits in Figure 4 indicate that the relative shear is more sensitive to the photometric period in giant stars compared to main-sequence stars. That picture confirms the distinction reported in Özdarcan (2021). Yet, the number of main sequence stars still requires to be increased, particularly for the shorter photometric periods for more reliable results. On the other hand, the distinction between giant and main sequence stars appears to be lost towards the longer photometric periods. Increasing the sample size of main sequence stars having long term continuous photometry is crucial for revealing the true form of the observed distinction between main sequence and giant stars. It is also desirable to observe main sequence stars with short photometric periods that appear below the dashed line in Figure 4). We may argue that these stars show less shear than the relation for longer period MS stars would predict.

In Figure 4, plotting the main sequence stars mentioned in Donahue et al. (1996) together with the target stars analysed in this study might be questionable because Donahue et al. (1996) obtained periods via the S index, which is a chromospheric indicator of the stellar activity, while we use pure V photometry (a photospheric indicator of the same phenomenon) to obtain periods. If the differential rotations of the photosphere and the chromosphere are significantly different from each other, then it is a reasonable concern. Since there are no long-term and simultaneous period measurements of the photo-sphere and the chromosphere of any star, we can only inspect the rotational behaviour of the solar photo-sphere and chromosphere and make interpretations in the scope of a solar-stellar connection. In a recent study, Xu et al. (2020) found that rotation periods indicated by chromospheric and photospheric indices vary in the same period range in the Sun (see Figure 6 in their study). This means that the differential rotation of the chromosphere of the Sun is not significantly different from the photosphere. A very recent study by Mishra et al. (2024) reported a 1.59% difference between the equatorial periods found from differential rotations of the solar photosphere and the chromosphere, which indicates a little difference between their rotations. Considering these findings, we may expect a similar behaviour for the chromospherically active stars in the scope of the Solar-Stellar connection. Then, it is reasonable to expect very little difference for SDR values computed from the S index (chromospheric indicator) and broadband V photometry (photospheric indicator). The difference would likely be within our observational errors.

We note that photometric periods are computed by tracing the rotational modulation signal observed in light curves. These signals are produced by cool surface spots. Rotation periods of these spots may be different depending on their latitudinal position on the surface of the star. This is the basic idea in our analysis. However, it was reported that any change in the area of a surface spot, vanishing and emerging of spots in short time scales at various locations on the surface of the star may alter the measured photometric period (Fekel et al. 2002). Such events show themselves as dramatic changes in the peak-to-peak light curve amplitude over short time scales (days). Even if these effects are in progress, we do not expect a significant change in our results because we determine photometric periods from stable parts of the light curves where the amplitude can be fairly accepted as constant.

Upon comparing the summarized findings with the theoretical computations of Kitchatinov & Rüdiger (1999), we observe that our results support the predicted relation between period and differential rotation. However, the observed distinction between giants and main sequence stars appears to be opposite to the theoretical predictions. According to calculations by Kitchatinov & Rüdiger (1999), giant stars should have stronger differential rotation compared to main-sequence stars. However, Figure 4 suggests the opposite, where the main-sequence stars appear to have stronger differential rotation than the giant stars. Further observational and theoretical studies may be conducted to investigate the source of this contradiction.

Kővári et al. (2017) investigated the relation between the rotation period and SDR in the scope of single and binary stars. They found that SDR weakly depends on the rotation period for of a binary system compared to a single star. We are not in a position to test this finding here since we do not consider single/binary distinction in our study. However, a further detailed investigation, which considers binarity and evolutionary status, might yield results that would provide a more comprehensive view of the relation between the SDR and the photometric period for chromospherically active stars.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)