1. Introduction

Information concepts have been applied to the investigation of diverse physical

phenomena for many years now. The concept of Shannon information entropy is

fundamental, being at the heart of spectroscopic studies. The foundation of

mathematical theory of communication or information theory was established by

Shannon in 1948 [1]. Shannon’s work focuses on

the basic notion, that is, entropy of information, which is widely known as the

Shannon entropy (SE). From the perspective of classical quantum theory, Shannon

entropy is a primary quantity which measures the average quantity of information

enclosed in a probabilistic message distributed distinctly. It was originally

associated with the complexity of a transmitted message. Shannon entropy signifies

uncertainty, prior to measurement, and an information quantity, post measurement, in

a probability distribution [2]. Besides

Shannon entropy of probability distribution being a vital cornerstone of the

traditional classical communication and computation, its relevance to new fields

such as, atomic, molecular and nuclear spectroscopy, applied mathematics, medical

science, chemistry, including quantum systems is aggressively under study [3-9]. In

recent years, several interesting applications of Shannon entropy have been

introduced. Shannon entropy is applied to characterize the high power laser systems,

assess and quantify information in spatially structured optical laser beams and to

present the automatic recognition of peak and baseline regions in large sets of

spectra [10-12]. The relation between the degree of polarization of a speckle

pattern and Shannon entropy is theoretically and experimentally investigated by Roy

[13]. Lee and Jung [14] investigated the influence of plasma shielding on Shannon

entropic values of atomic states and used Shannon entropy as a powerful tool in

plasma spectroscopy. The range of applicability has been extensively extended to

atomic, molecular and nuclear spectroscopy including study of different properties

like ionization potential, global delocalization, molecular geometric parameters,

reaction paths and highly excited states of single particle systems [15-19].

Filho [20] used hydrogen atom as a basis to

demonstrate the use of Shannon entropy in a paraconsistent model for modeling

quantum systems. Entropy minimisation approach is applied to remove specularities

from imaging spectroscopy data [21]. This

list just scratches the surface and is continuously expanding as information entropy

provides a deeper insight into complexity of quantum systems [22-26]. The study of

hydrogen atom is one of the main driving forces in the development of quantum

mechanics with the first step by Ernest Rutherford in 1911. Atomic hydrogen and

hydrogen like ions form the most elementary systems in atomic physics and are found

in different types of plasmas [27-29]. The resonance lines in hydrogenlike

chromium are observed in Tokamak fusion test reactor plasma [30]. High resolution spectra of hydrogen-like titanium are

observed in Tokamak discharges using high resolution spectrometer. In addition to

the

The idea of isoelectronic sequence plays an important role in atomic physics, fundamental spectroscopic studies as well as in various engineering branches, through which the atomic structure can be studied systematically along with atomic number Z under the condition of identical number of electrons. Shannon entropy was used as a tool to obtain the ground and excited states in the configuration space of nickel isoelectronic sequence [39]. With the fusion of information theory and chemistry, many concepts such as orbital free density functional theory, electron correlations, de-coherence, configuration interaction, chemical reactivity, entanglement in artificial atoms, atomicity, characterization of chemical processes and localization properties of Rydberg states of atoms can be elucidated by applying Shannon entropy model to isoelectronic series [40-42]. Hydrogen-like ions are ideally suited to study the important mechanism of direct ionization further contributing to the understanding of atomic processes [43]. Information entropies are a hidden treasure and are effectively employed to explore the atomic properties along the hydrogen isoelectronic sequence [44]. Gadre et al. [45] computed Shannon entropy for the ground and excited states of free hydrogen atom. The role of Shannon entropy as an indicator of atomic avoided crossings, the most distinctive atomic spectroscopic feature, is studied based on the dynamics of some excited states of hydrogen in strong parallel electric and magnetic fields [46]. Kumar and Kumar [47] evaluated the information entropy of hydrogen atom using the isospectral Hamiltonian approach. Further, He et al. [48] employed Shannon entropy as a competent parameter for characterization and prediction of avoided crossings of Rydberg potassium atoms in a static electric field and calculated Shannon entropy for field-free hydrogen atom. Mukherjee and Roy [49] presented information entropic measurements for free and confined hydrogen atom. Astronomical data of atomic Shannon entropy for the ground and excited states of hydrogen atom in astrophysical Lorentzian plasmas are obtained and the non-thermal effects on variation in Shannon entropy is investigated by Lee and Jung [50]. There have been multiple attempts in literature to portray correlation and relativistic effects in terms of Shannon information entropy from the perspective of differences in electron density due to these effects [51-54]. In this direction, Martínez-Sánchez et al. [55] judged Shannon entropy to be a useful indicator of localization and delocalization of electron density of the ground state as well as excited states of hydrogen atom.

The primary objective of this work is to calculate Shannon entropy with numerical simulation to obtain the exact wave functions for free hydrogen atom (FHA) and hydrogen isoelectronic sequence for atomic number Z ≤ 30. Shannon entropy is presented for all acceptable l’s corresponding to a given n (n = 1 − 10), keeping m = 0; where n, l, m, are principal, orbital and magnetic quantum numbers, respectively. Global behavior of Shannon entropy is analyzed and three conjectures are evaluated, (i) the behavioral pattern of Shannon entropy with respect to atomic number Z (ii) dependence of Shannon entropy on principal quantum number n for a fixed orbital quantum number l (iii) dependence of Shannon entropy on orbital quantum number l for a fixed principal quantum number n. In the past few years, appreciable entropy computations have been done for free hydrogen atom. However, it is worth mentioning here that most of the investigations performed in the past are restricted to the ground state and the lower excited states of hydrogen atom while not much attention has been paid to the entropic measurements of the excited states of hydrogen isoelectronic sequence for low to medium atomic number Z. The present work bridges this gap in the database and provides benchmark values for Shannon information entropies.

2. Method

Starting with the non-relativistic Hamiltonian for the hydrogenic atom:

Since

We have

Solution of the time independent Schrödinger equation

are

where Y l,m (θ,φ) are the standard spherical harmonics. The operator L2 acts only on the angular variables and we get

On substituting u n,l (r) = r R n,l (r) , the radial equation becomes

Solution of Eq. (8) gives the stationary state energies and wave functions.

For the present calculations, Numerov method is adopted to solve the radial part of the Schrodinger equation.¨ The method was developed by Russian astronomer Boris Vasilyevich Numerov [56-57] and is generally applied to solve ordinary differential equations of second order without the first order differential term. The radial equation for central potentials can be converted into such equation by minor substitutions (as in the present case Eq. (8) is obtained by substituting u n.l (r) = rR n,l (r)) . Therefore, the Numerov method can be used for the solution of one-dimensional Schrodinger¨ equation or radial Schrodinger equation in three dimensions¨ as the first order term gets eliminated from it [58]. In the present calculations, Numerov method [59] starts with a differential equation of the form

The centered difference technique is applied to get;

with y n = y(x n ) gives the Numerov expression:

where F n = P(x n ) + Q(x n )y n and h is the spatial grid step in Numerov Method. The method results in very accurate values of energies and wave functions as the error achieved is of O(h 6). The computational effort is also reduced as it is needed to calculate the functions P and Q only once in every step while the traditional Runge Kutta method requires these functions to be calculated six times in each step. In our case we can apply Numerov method described above to solve Eq. (8).

A singularity at r = 0 is encountered while solving Schrödinger’s equation. To solve this issue, one might employ the variable step grid rather than the constant step grid. For this purpose a logarithmic grid is employed in the present work. A new variable, t is introduced, so that the grid is equally spaced in terms of t. Here t = log(Zr) and

with t min = −8 which gives Zr min = 0.0034. As t min becomes more and more negative, r min becomes smaller and smaller but does not attain the value zero. The number of points in the grid is given by:

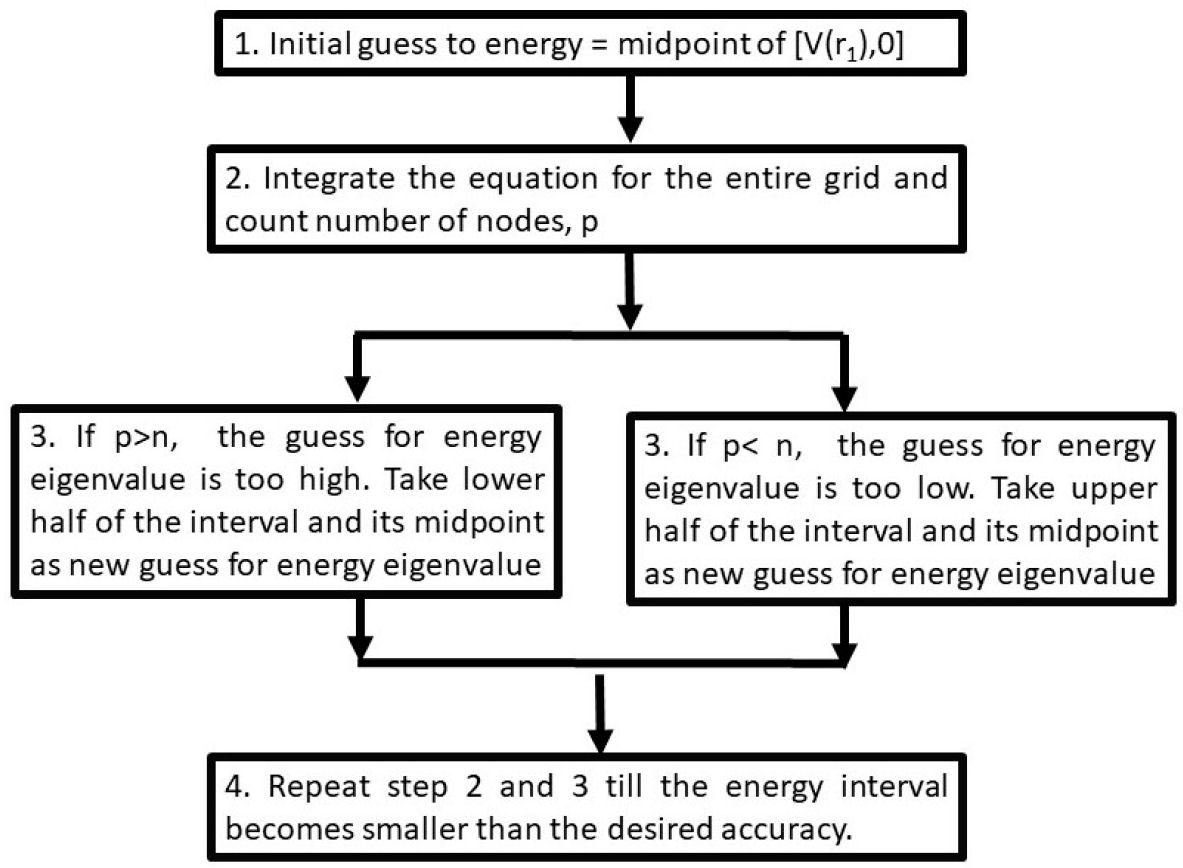

The first step in calculating the energy eigenvalue is to take an initial energy range in which the energy eigenvalue lies. The energy eigenvalue is assumed to be at the midpoint of this energy range. The wave function from r = 0 to the positive side is integrated, and the nodes are counted. The energy is too high and the lower half of the energy range is chosen for the following iteration if the number of nodes is greater than the principal quantum number n, otherwise the upper half is chosen. In each repetition, the energy interval is cut into half in this way. So, after a few iterations, the energy eigenvalue is obtained as accurate as desired. The first approximation to the energy value should be greater than the potential function value at the first grid point. This algorithm can be visualized as follows:

After obtaining the energy eigenvalues and wavefunctions using Numerov method, the probability density and Shannon entropy is calculated as: Z

where

where R nl (r) and Y lm (Ω) being the radial and angular parts of the wavefunctions. Shannon Entropy S r can also be written as the sum of radial and angular parts given by:

where

and

3. Results and discussion

Results are reported for the calculation of Shannon entropy of the ground state and the excited states n ≤ 20; l ≤ 9, m = 0 (n, l, m, are principal, orbital and magnetic quantum numbers, respectively) of free hydrogen atom and hydrogen isoelectronic sequence for all elements in the first and second row of the periodic table along with three specific ions with atomic number Z = 15, 20, 25; namely, hydrogen-like phosphorus, calcium and manganese. For the present calculations, the position space is descretized into a logarithmic grid with ∆t = 0.01, t min = − 8 and r max = 100 − 500, suitably selected to ensure proper convergence of the results up to minimum eight decimal places.

To test the accuracy of the present method, the computed Shannon entropy results for field-free hydrogen atom are compared with a few selected orbitals already available in literature. In Table I comparison is made with the calculated values of Mukherjee and Roy [49]. As is evident from the percentage deviation displayed in Table I, the present results are in very good agreement with the other calculated values although the method used in these calculations is quite different from that used by Mukherjee and Roy. They have expressed the wave functions in terms of Gegenbauer polynomials, while in the present work we have used the fast and efficient Numerov method. This excellent comparison gives credence to the accuracy of the applied method to yield reliable results. Further, calculations are performed to predict new data for several states of free hydrogen atom and hydrogen isoelectronic sequence corresponding to atomic number Z ≤ 30. Tables II-IV report detailed values of Shannon entropy (SE) and explore all the l states (l = n−1 to l = 0) corresponding to each value of n (n = 1 − 5) for free hydrogen atom and hydrogen-like systems with atomic number Z spanning 1-25. It is seen that Shannon entropy (SE) is the lowest for 1s (nl: n = 1, l = 0) orbital for all the atomic systems under study. This is consistent with the fundamental notion that the ground state corresponds to the most compact distribution. Tables II-IV display the trend for nl states (l = 0,s; l = 1,p; l = 2,d; l = 3,f; l = 4,g): SE(1s) (4.14472988) < SE(2p) (7.26489710) < SE(2s)(8.11092930) < SE(3d) (9.34563418) < SE(3p) (9.80584650) < SE(3s) (10.42648180)< SE(4f) (10.86085518) < SE(4d) (11.26210457) < SE(4p) (11.53386532) < SE(5g) (12.04980084) < SE(4s) (12.07490903) < SE(5f) (12.42371304) < SE(5d) (12.65962026) < SE(5p) (12.85433726) < SE(5s) (13.35756972) for free hydrogen atom. Similar to free hydrogen atom, hydrogen isoelectronic sequence with atomic number Z ≤ 25 also portrays analogous trend as shown above. Shannon entropy goes up steadily with the principal quantum number n when the orbital quantum number l stays the same, but it goes down with the orbital quantum number l when the principal quantum number n stays the same, as also indicated in the Figs. 4 and 5 later. It displays the order of localization of electron density of different orbitals in free hydrogen atom and the hydrogen isoelectronic sequence under study. It is notable that information entropy values for hydrogen-like ions are systematically presented for the first time and will provide useful information in the study of free one-electron atomic systems in future.

TABLE I Shannon entropy for hydrogen atom for orbitals with the principal quantum number n ranging from 1-10 and orbital quantum number l ranging from (n −1)−0 as compared with Mukherjee and Roy [49]. We also present percent deviation between the current results and Mukherjee and Roy [49].

| n | l | Mukherjee and Roy [49] | Present results | Percent Deviation |

| 1 | 0 | 4.1447298858 | 4.14472988 | 1.40×10−7 |

| 2 | 1 | 7.2648971185 | 7.26489710 | 2.54×10−7 |

| 2 | 0 | 8.110929364 | 8.11092930 | 7.90×10−7 |

| 3 | 2 | 9.3456342021 | 9.34563418 | 2.36×10−7 |

| 3 | 1 | 9.805847064 | 9.80584650 | 5.75×10−6 |

| 3 | 0 | 10.42648123 | 10.42648180 | 5.47×10−6 |

| 4 | 3 | 10.8608551995 | 10.86085518 | 1.80×10−7 |

| 4 | 2 | 11.2621041941 | 11.26210457 | 3.34×10−6 |

| 4 | 1 | 11.533867248 | 11.53386532 | 1.67×10−5 |

| 4 | 0 | 12.074907679 | 12.07490903 | 1.12×10−5 |

| 10 | 9 | 15.7888444089 | 15.78884437 | 2.46×10−7 |

| 10 | 8 | 16.1121461768 | 16.11215058 | 2.73×10−5 |

| 10 | 7 | 16.3107700381 | 16.31077913 | 5.57×10−5 |

| 10 | 6 | 16.4572511655 | 16.45726330 | 7.37×10−5 |

| 10 | 5 | 16.5730314451 | 16.57305427 | 1.38×10−4 |

| 10 | 4 | 16.6677376254 | 16.66771446 | 1.39×10−4 |

| 10 | 3 | 16.7475932108 | 16.74762694 | 2.01×10−4 |

| 10 | 2 | 16.8206447121 | 16.82066183 | 1.02×10−4 |

| 10 | 1 | 16.914539415 | 16.91455534 | 9.41×10−5 |

| 10 | 0 | 17.365242257 | 17.36524825 | 3.47×10−5 |

TABLE II Shannon entropy for hydrogen isoelectronic sequence with atomic number Z ranging from 1-5, for orbitals with the principal quantum number n ranging from 1-5 and orbital quantum number l ranging from (n −1)−0.

| n | l | Z = 1 | Z = 2 | Z = 3 | Z = 4 | Z = 5 |

| 1 | 0 | 4.14472988 | 2.06528834 | 0.84889302 | -0.01415319 | -0.68358384 |

| 2 | 1 | 7.26489710 | 5.18545556 | 3.96906024 | 3.10601403 | 2.43658337 |

| 2 | 0 | 8.11092930 | 6.03148776 | 4.81509244 | 3.95204622 | 3.28261557 |

| 3 | 2 | 9.34563418 | 7.26619264 | 6.04979732 | 5.18675111 | 4.51732045 |

| 3 | 1 | 9.80584650 | 7.72640496 | 6.51000964 | 5.64696343 | 4.97753277 |

| 3 | 0 | 10.42648180 | 8.34704026 | 7.13064494 | 6.26759872 | 5.59816807 |

| 4 | 3 | 10.86085518 | 8.78141364 | 7.56501831 | 6.70197210 | 6.03254145 |

| 4 | 2 | 11.26210457 | 9.18266303 | 7.96626771 | 7.10322149 | 6.43379084 |

| 4 | 1 | 11.53386532 | 9.45442378 | 8.23802845 | 7.37498224 | 6.70555159 |

| 4 | 0 | 12.07490903 | 9.99546749 | 8.77907217 | 7.91602595 | 7.24659530 |

| 5 | 4 | 12.04980084 | 9.97035929 | 8.75396397 | 7.89091776 | 7.22148711 |

| 5 | 3 | 12.42371304 | 10.34427151 | 9.12787618 | 8.26482996 | 7.59539931 |

| 5 | 2 | 12.65962026 | 10.58017872 | 9.36378339 | 8.50073718 | 7.83130652 |

| 5 | 1 | 12.85433726 | 10.77489572 | 9.55850040 | 8.69545418 | 8.02602353 |

| 5 | 0 | 13.35756972 | 11.27812819 | 10.06173287 | 9.19868665 | 8.52925599 |

TABLE III Shannon entropy for hydrogen isoelectronic sequence with atomic number Z ranging from 6-10, for orbitals with the principal quantum number n ranging from 1-5 and orbital quantum number l ranging from (n −1)−0.

| n | l | Z = 6 | Z = 7 | Z = 8 | Z = 9 | Z = 10 |

| 1 | 0 | -1.23054851 | -1.69300055 | -2.09359473 | -2.44694383 | -2.76302538 |

| 2 | 1 | 1.88961871 | 1.42716667 | 1.02657249 | 0.67322338 | 0.35714184 |

| 2 | 0 | 2.73565090 | 2.27319886 | 1.87260468 | 1.51925558 | 1.20317403 |

| 3 | 2 | 3.97035578 | 3.50790374 | 3.10730957 | 2.75396046 | 2.43787892 |

| 3 | 1 | 4.43056810 | 3.96811607 | 3.56752189 | 3.21417278 | 2.89809124 |

| 3 | 0 | 5.05120340 | 4.58875136 | 4.18815719 | 3.83480808 | 3.51872653 |

| 4 | 3 | 5.48557678 | 5.02312474 | 4.62253056 | 4.26918145 | 3.95309991 |

| 4 | 2 | 5.88682617 | 5.42437413 | 5.02377995 | 4.67043085 | 4.35434930 |

| 4 | 1 | 6.15858692 | 5.69613488 | 5.29554070 | 4.94219160 | 4.62611005 |

| 4 | 0 | 6.69963063 | 6.23717859 | 5.83658442 | 5.48323531 | 5.16715376 |

| 5 | 4 | 6.67452244 | 6.21207040 | 5.81147622 | 5.45812711 | 5.14204557 |

| 5 | 3 | 7.04843464 | 6.58598260 | 6.18538843 | 5.83203932 | 5.51595777 |

| 5 | 2 | 7.28434186 | 6.82188982 | 6.42129564 | 6.06794653 | 5.75186499 |

| 5 | 1 | 7.47905886 | 7.01660682 | 6.61601265 | 6.26266354 | 5.94658199 |

| 5 | 0 | 7.98229132 | 7.51983928 | 7.11924511 | 6.76589600 | 6.44981446 |

TABLE IV Shannon entropy for hydrogen isoelectronic sequence with atomic number Z = 15,20 and 25, for orbitals with the principal quantum number n ranging from 1-5 and orbital quantum number l ranging from (n −1)−0.

| n | l | Z = 15 | Z = 20 | Z = 25 |

| 1 | 0 | -3.97942070 | -4.84246692 | -5.51189757 |

| 2 | 1 | -0.85925348 | -1.72229969 | -2.39173034 |

| 2 | 0 | -0.01322128 | -0.87626750 | -1.54569815 |

| 3 | 2 | 1.22148359 | 0.35843738 | -0.31099327 |

| 3 | 1 | 1.68169591 | 0.81864970 | 0.14921905 |

| 3 | 0 | 2.30233121 | 1.43928500 | 0.76985434 |

| 4 | 3 | 2.73670459 | 1.87365837 | 1.20422772 |

| 4 | 2 | 3.13795398 | 2.27490776 | 1.60547711 |

| 4 | 1 | 3.40971473 | 2.54666851 | 1.87723786 |

| 4 | 0 | 3.95075844 | 3.08771223 | 2.41828157 |

| 5 | 4 | 3.92565025 | 3.06260403 | 2.39317338 |

| 5 | 3 | 4.29956245 | 3.43651624 | 2.76708558 |

| 5 | 2 | 4.53546967 | 3.67242345 | 3.00299280 |

| 5 | 1 | 4.73018667 | 3.86714046 | 3.19770980 |

| 5 | 0 | 5.23341913 | 4.37037292 | 3.7009422 |

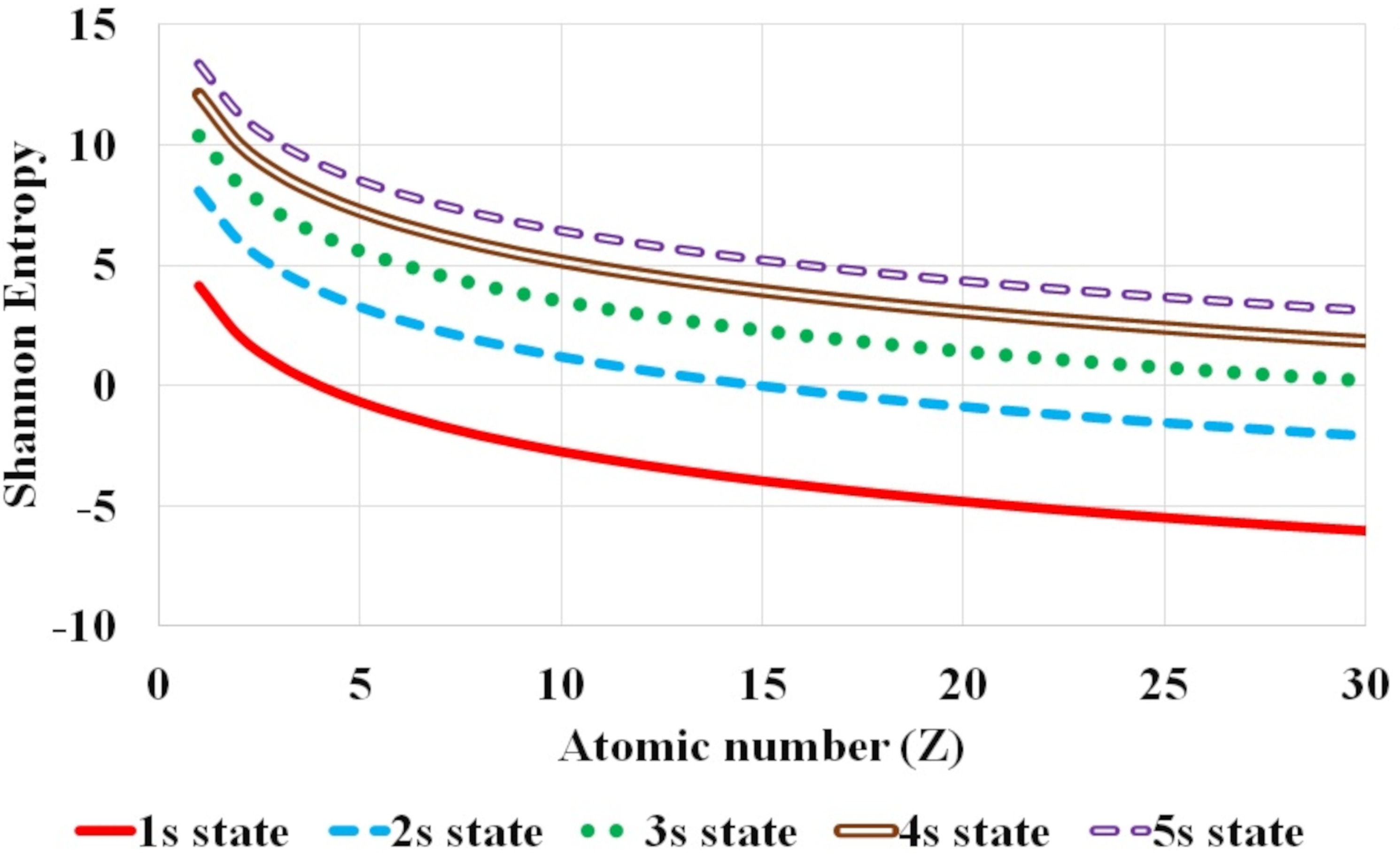

FIGURE 1 Variation of Shannon entropy with atomic number Z for hydrogen isolelectronic sequence for the first five nl atomic states corresponding to n principal quantum number with fixed l orbital quantum number equal to 0, namely s states (1s −5s).

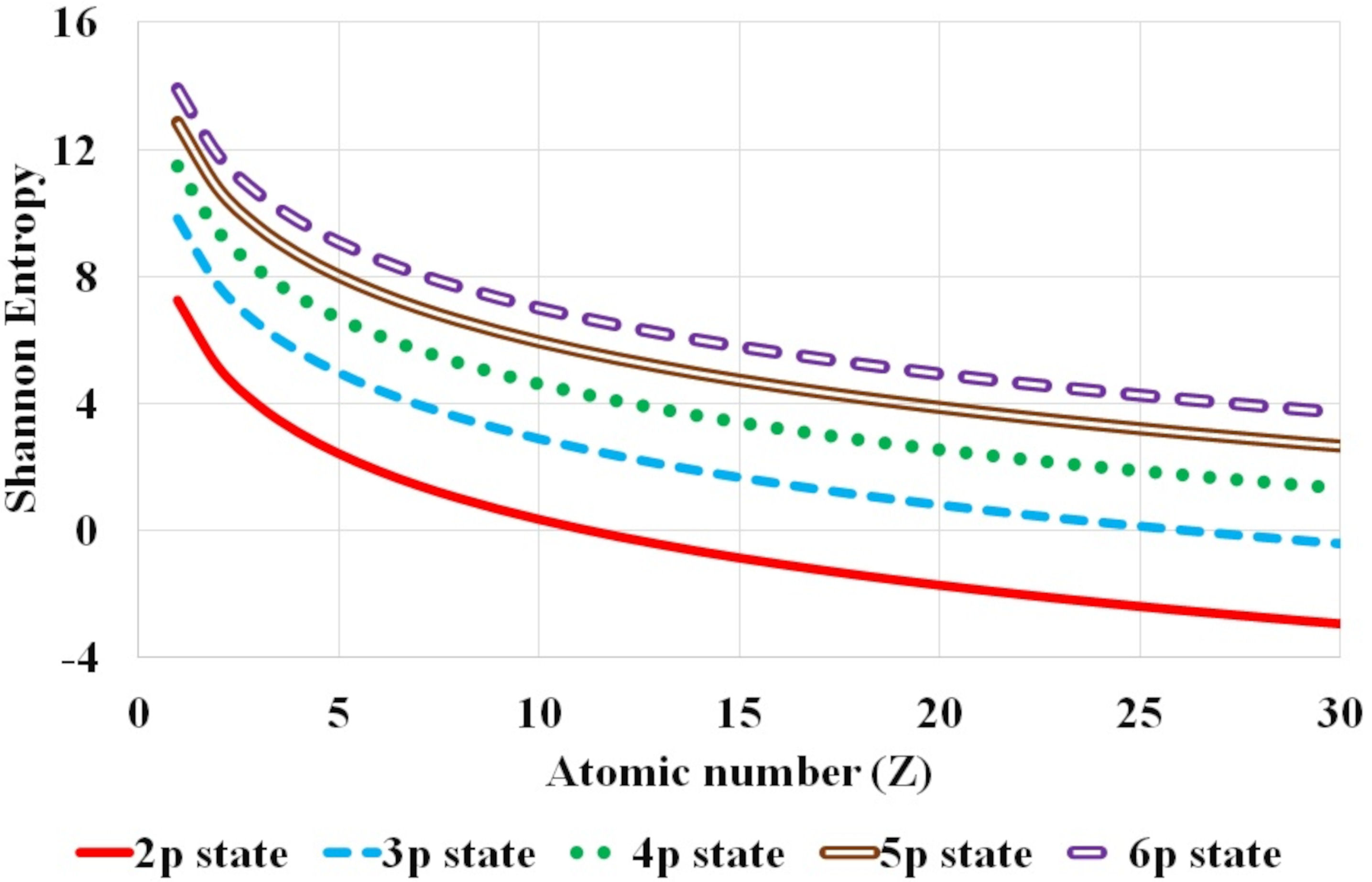

FIGURE 2 Variation of Shannon entropy with atomic number Z for hydrogen isolelectronic sequence for the first five nl atomic states corresponding to n principal quantum number with fixed l orbital quantum number equal to 1, namely p states (2p −6p).

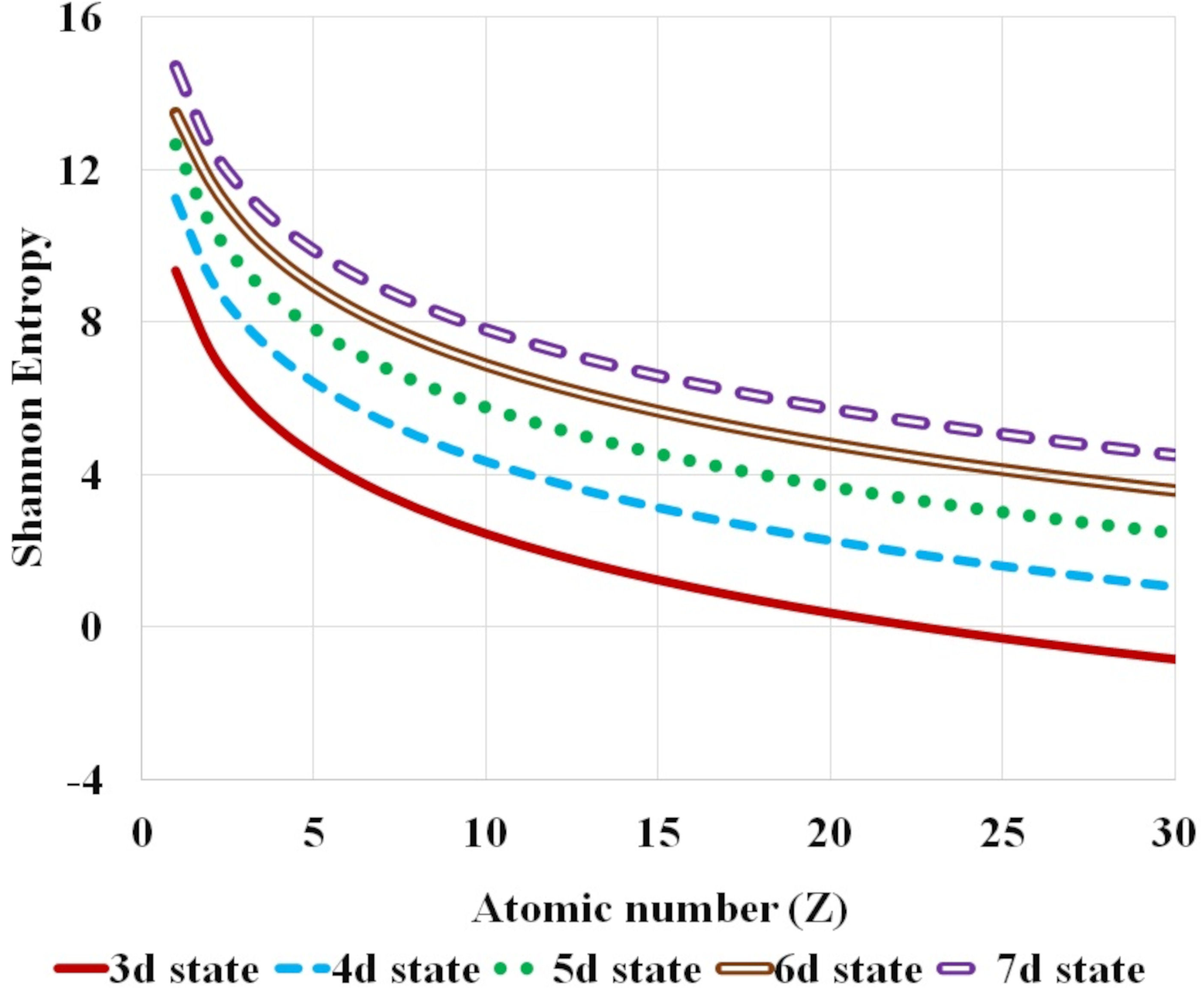

FIGURE 3 Variation of Shannon entropy with atomic number Z for hydrogen isolelectronic sequence for the first five nl atomic states corresponding to n principal quantum number with fixed l orbital quantum number equal to 2, namely d states (3d −7d).

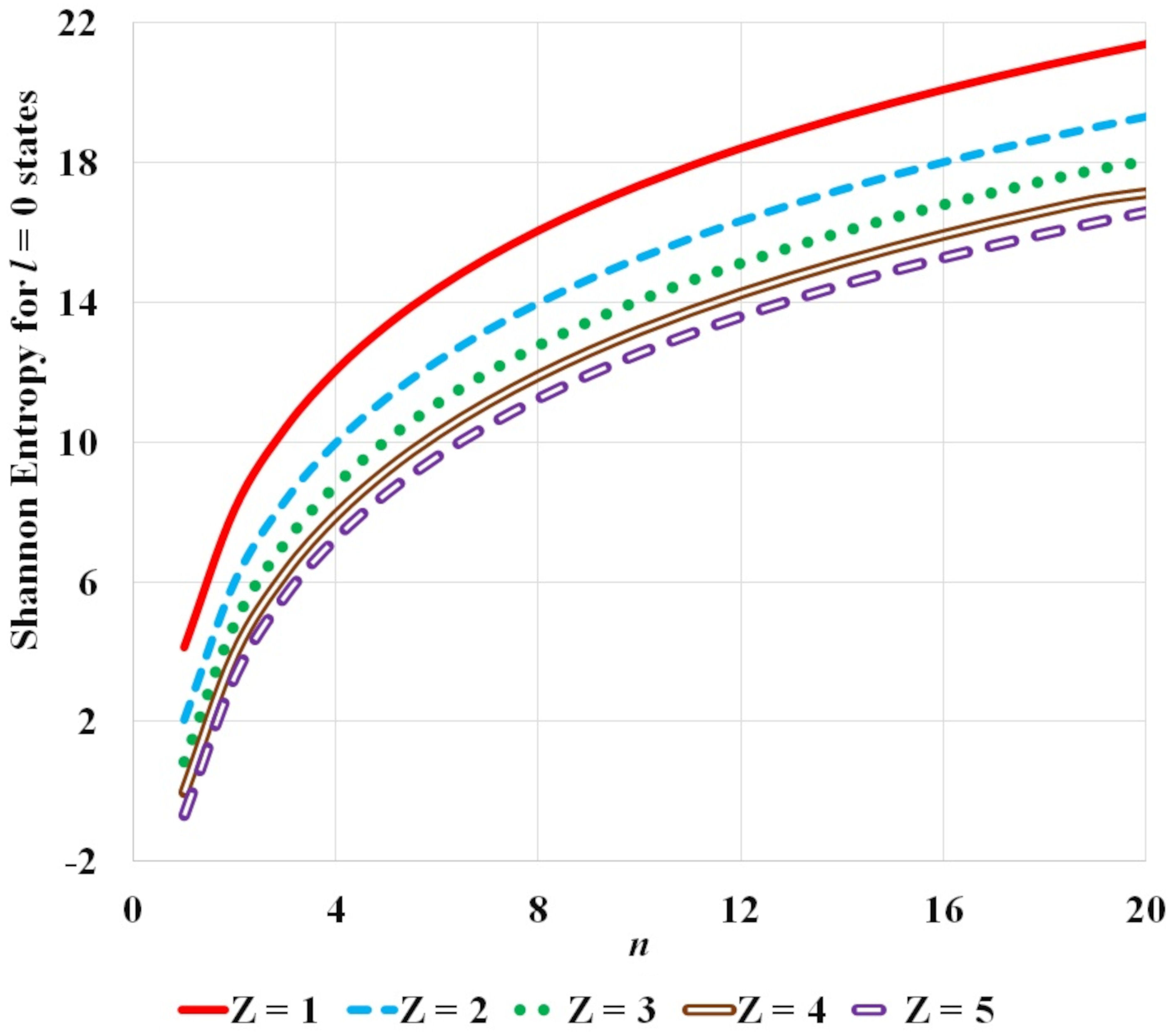

FIGURE 4 Variation of Shannon entropy with n principal quantum number for hydrogen isoelectronic sequence for atomic states corresponding to fixed l orbital quantum number equal to 0 and for atomic number Z = 1−5.

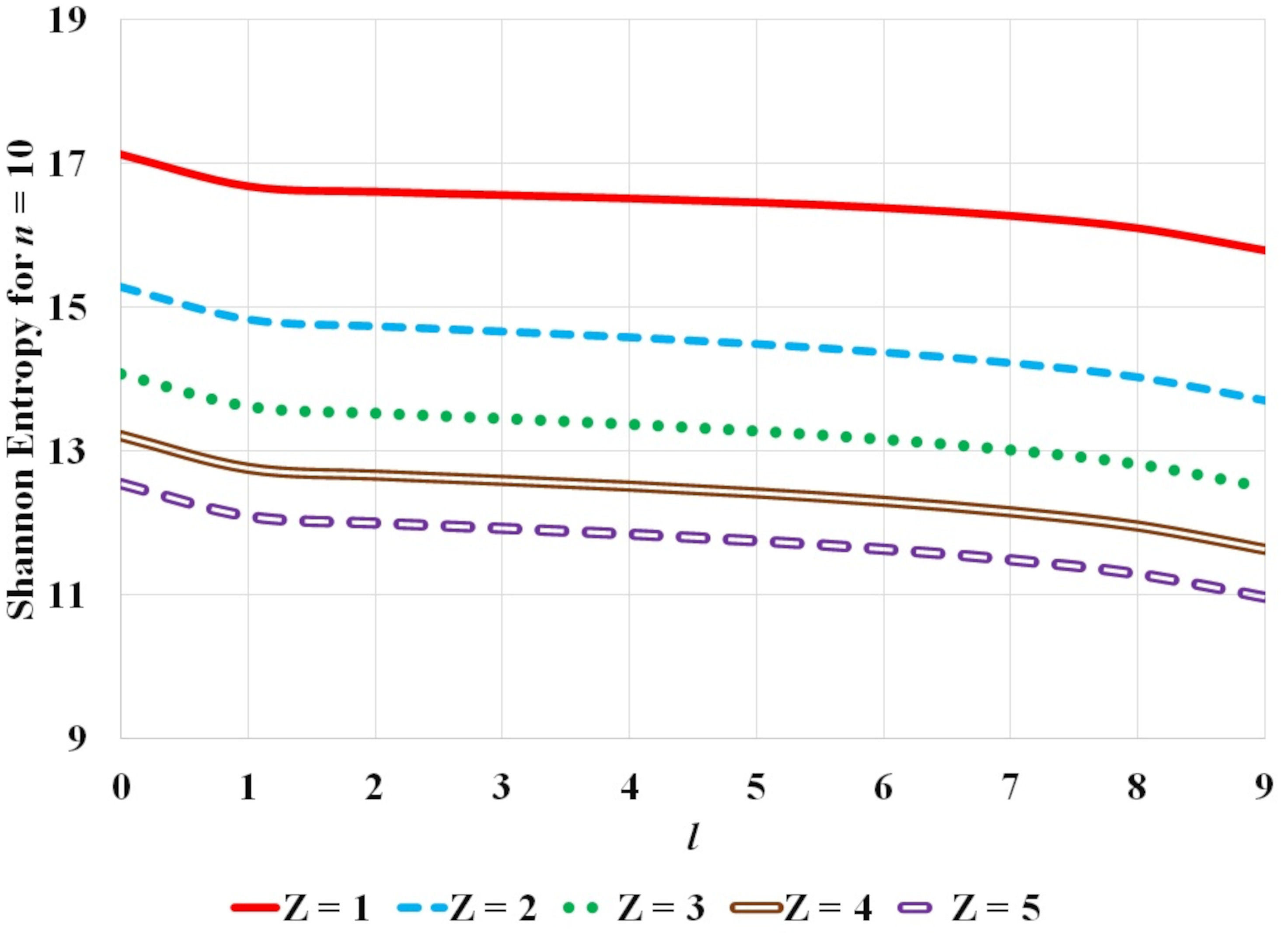

FIGURE 5 Variation of Shannon entropy with l orbital quantum number for hydrogen isoelectronic sequence for atomic states corresponding to fixed n principal quantum number equal to 10 and for atomic number Z = 1−5.

Further, the systematic variation of Shannon entropy with respect to atomic number Z and the global dependence of Shannon entropy on n and l, principal and orbital quantum number respectively, is analyzed. Figures 1-3 plot this variation of Shannon entropy with the atomic number Z (Z ≤ 30) for various atomic orbitals. The first five atomic states with l = 0, 1 and 2 are shown in Fig. 1, 2 and 3 respectively. The shift in Shannon entropy with respect to atomic number Z in hydrogen isoelectronic sequence is noted. The electron density is localized or confined for high values of atomic number.

It is observed that the Shannon entropy decreases with increase in atomic number. This trend is observed for the ground as well as the excited states of hydrogenic sequence under study. Figures 1-3 also illustrate that entropy enhances with the principal quantum number n. As one moves along the hydrogen isoelectronic sequence, Shannon entropy decreases as localization increases. This study corroborates the concept that position entropy indicates that the position of the particle is ambiguous. These observations are further reiterated in Fig. 4 and Fig. 5. In Fig. 4, variation in Shannon entropy is noted for a fixed orbital quantum number l = 0 in various excited states with principal quantum number n = 1 − 20, for atomic number Z = 1 − 5. It is inferred from Fig. 4 that each hydrogenic ion exhibits a rapid rise in entropy for smaller values of principal quantum number n (say, n ≤ 15) and at a slower rate for larger principal quantum number n. This is in conformity with that as principal quantum number n rises, the radial orbitals get extended in space. Figure 5 portrays the variation in Shannon entropy with all l states corresponding to n = 10 states for hydrogen isoelectronic sequence with atomic number Z = 1 − 5. It is observed that the position entropy globally decreases with orbital quantum number l for a fixed principal quantum number n (in this case n = 10).

Figure 4 exhibits the variation of Shannon entropy with principal quantum number n (n = 1 − 20) for a fixed orbital quantum number l = 0 while Fig. 5 shows the variation of Shannon entropy with orbital quantum number l (l = 0 − 9) for a fixed principal quantum number n = 10, corresponding to free hydrogen atom and hydrogen isoelectronic sequence along hydrogen-like helium to hydrogen-like boron with atomic number Z = 1 − 5. The increase or decrease in the Shannon entropy is a reflection of the extension or contraction of the density distribution corresponding to the expansion or localization of the wave function. At orbital quantum number l = 0 the density distribution is flat, so the Shannon entropy is large. For the same value of principal quantum number n, as orbital quantum number l increases the electron gets more localized and the density distribution gets concentrated so the Shannon entropy diminishes.

These results affirm the interpretation that Shannon entropy ascertains density distribution and marks a measure of uncertainty in the spatial location of the particle. A more localized distribution is characterized by a smaller value of Shannon entropy while a spread in density distribution corresponds to an increment in Shannon entropy. These calculations of Shannon information entropies in atomic systems could assist spectroscopists in a deeper understanding of the spread of electron density, diffusion of atomic orbitals, periodic properties and correlation energy [60-61]. To the best of our knowledge, the data has not been presented earlier and can be used by other authors for performing further calculations of different parameters of these ions.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, elaborate calculations of Shannon entropy are presented for free hydrogen atom and extended to hydrogen isoelectronic sequence with atomic number Z ≤ 30 for the ground state and the excited states n ≤ 20 corresponding to both zero l states (s states) and non-zero l states (p − m), namely 1s−10m (n, l are principal and orbital quantum number, respectively) using the competent Numerov method. The computed results are in excellent agreement with the available results in literature. New entropic values are reported for higher excited states of hydrogen-like ions which will be useful for future referencing and stimulate further research in this direction to study the diffused nature of orbitals. In addition, variation of Shannon entropy with atomic number Z and the state of excitation is analyzed for the systems under study. A thorough examination suggests that for any arbitrary nl state an increase in atomic number Z stimulates localization. Consequently, as one moves to heavier atoms the electron density gets more compact. In addition to the above mentioned behavior of entropy with atomic number Z, a global decrease and monotonic increase in Shannon entropy is observed on fixing principal quantum number n and changing orbital quantum number l and vice versa. These observations reinforce the beauty in the pattern of periodic trends in chemistry for ionization energy, electronegativity, ionic radius, electron affinity, etc. of atomic systems. The present computations of Shannon information entropies can be potentially applied by spectroscopists to analyze the quantum chaotic systems to designate the extent of localization and complexity of an electron cloud based on one-electron orbitals or density distribution. It is hoped that the study will reveal a deeper knowledge of density functionals and distinct spectroscopic phenomena to investigate the structure and dynamics of atomic systems and will help in a better interpretation, diagnostics and understanding of spectroscopic data.

Data availability statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available within the article.

Declaration of competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests to disclose.

Author contribution statement

All authors contributed equally to the article.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)