1 Introduction

Under extreme conditions of pressure and temperature, the chemistry of materials, as we know it, changes drastically, making it possible to access new states of matter. Thus, experimental and theoretical research under extreme conditions have been fundamental in their contribution to geophysics, planetary sciences, and mineralogy, as well as to the characterization of new materials of technological interest and their respective phase diagrams, leading to a better understanding of their physical and chemical properties. In this sense, the fundamental study of diatomic molecules of single elements with low atomic numbers subjected to high-pressure conditions, has been the subject of great interest by the scientific community due to the theoretical and experimental detection of phenomena, such as the eventual metallization induced by pressure or phase transformations observed in analogous mono-atomic systems such as nitrogen [1, 2] and the halogen elements [3, 4, 5, 6]. Fluorine is the first of the halogens and the last of the diatomic elements of the first row in the periodic table. It was chosen as the study object of this work given its similarities with hydrogen and the high energy density of its electronic bonds, likewise, it is an abundant element in the universe and is particularly interesting for its high oxidizing capacity and for having the highest electronegativity among all elements, followed by oxygen’s.

Despite the above reasons, fluorine has not been studied very extensively if compared to other single-element diatomic molecules (H2, N2, O2, Cl2, Br2, and I2). For instance, the space group of solid fluorine at high pressure remained controversial for many years because two different structures were proposed through spectroscopy studies and theoretical calculations, respectively [7,

8,

9,

10]. Experiments were carried out using diamond anvil cells (DAC), but it was very challenging to obtain reliable results [10,

11]. In addition to the very small sample sizes that are typical of experiments involving DACs, other technical difficulties came from the fact that fluorine and other halogen elements are characterized by being volatile, corrosive, and highly reactive, increasing the complexity level when studied in the lab. For this reason, it was not until a few years ago that, by using computational techniques, a study established that the

Given the substantial differences observed in recent theoretical reports at TPa pressures for solid fluorine, validating the structures found in Refs. [13, 15] is necessary. For this study, we chose the computational tool for crystal structure determination known as USPEX [17, 18, 19, 20], which is currently one of the most reliable codes used within the materials science community and combines ab-initio methods with structure prediction techniques based on evolutionary algorithms. In the past, USPEX has been able to predict new phases of materials at high pressure, including some up to 350 GPa that are relevant to the Earth’s interior, allowing new ways of understanding matter at extreme conditions.

In this work, we tested USPEX’s abilities by performing meticulous structural searches of fluorine crystalline phases, varying the number of atoms per unit cell and repeating this process at different volumes that correspond to TPa conditions of pressure. All this, interfaced with Quantum ESPRESSO [21, 22] as the selected tool for accurate ab-initio structural relaxations, as detailed in the Methods section. The Results and Discussion section provides our research’s findings and analysis for several candidate-structures. Finally, we present our main conclusions in the last section, by providing answers regarding the coordination nature, electronic character and range of stability of fluorine’s high pressure phases in the range from 1 to 5 TPa.

2 Methods

In view of the previous contradicting results, regarding the predicted sequence of transitions when going from molecular to extended forms of solid fluorine, the main objective of this work is to provide an independent insight by using a different methodological approach for performing the structural search of novel phases of this element in the Tera-Pascal regime. Over the past years, the likelihood of obtaining reliable results with computing methods for crystal structure prediction has been improved substantially. In this work, we have selected the USPEX package for its proven robustness in pressure regimes similar to the one of this study. In the initial stage we used USPEX to successfully generate good candidate structures for solid fluorine, followed by density functional theory (DFT) calculations for the structural optimization and refinement of selected candidate phases at different pressures. In addition, the density functional perturbation theory (DFPT) scheme allowed us to determine the dynamical stability of the structures that were found, from vibrational data.

2.1 USPEX calculations

USPEX employs an evolutionary algorithm to generate different structures of solid crystals, which is mostly unbiased because it only uses information that the researcher provides about the number and type of atoms to be contained within the crystalline unit cell [17, 18, 19, 20]. At first, the initial setof structures is generated by randomly choosing any crystal space group. Thus, this first generation is mainly composed of arbitrary far-of-equilibrium structures. It is then necessary to perform a structural relaxation to decrease and determine the total internal energy of each candidate system and use that value as a fitness criterion. Then, after a purely random start, new generations are created via genetic operations which can apply criteria such as heredity, mutation, and permutation; nevertheless, a portion of the new structures is still made randomly to ensure a level of diversity in each generation. The structural search ends when one of these criteria is achieved: no new best structure is generated for a certain number of generations, or, the set value for the maximum number of generations is reached.

Here, fixed composition searches were conducted to determine suitable high-pressure phases for solid fluorine. USPEX-based structure predictions were performed independently on different cell sizes, containing 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 16 atoms, in a pressure range spanning from 1.0 to 5.0 TPa in steps of 0.5 TPa, with the exception of 1.5 TPa that was not considered explicitly in this work but interpolated instead. Also, the two biggest cell sizes (12 and 16 atoms) were studied at four selected pressures instead of eight, and interpolated for the other pressures in that same range. The USPEX calculations started with an initial population of 30 structures, generated randomly with no restrictions on the space groups that could be assigned to the structures. In addition, no seeds or anti-seeds were considered. Subsequent generations were produced by applying the following variation operations (in parenthesis are the weights used in this work): heredity (50%), soft-mutation (15%), lattice mutation (10%), and permutation (5%), while the rest of the newly generated structures (20%) were still randomly produced with the random symmetric structure generator to assure diversity as explained earlier. We set the maximum number of generations to 50, and the convergence criterion was set to 20 repetitions of the same prediction. All USPEX calculations ended by reaching the repeated best structure convergence criterion.

2.2 DFT Calculations

The trial structures were optimized in a low-to-high precision process using first-principles DFT calculations using the Quantum Espresso suite [21,

22] for variable-cell relaxation. We increased the convergence criteria and precision settings at each step, with a reciprocal space resolution for k-point generation of 0.20, 0.16, and 0.12

3 Results and discussion

We began our exploration by first keeping present the structures that were reported in previous studies up to 5.0 TPa [12,

13,

15]: Cmca,

Table I Structural information of previously reported structures for high-pressure phases of fluorine.

| Space group Pressure |

Lattice parameters (Å,°) |

Atomic coordinates (fractional) |

|---|---|---|

| (64)Cmca | a = 4.31 | 8f |

| .02 TPa | b = 2.88 | y = 0.3799 |

| Ref. [12] | c = 5.84 | z = 1.3933 |

| α = β = y =90 | ||

| (131) P42/mmc | a = 2.69 | 2a |

| .75 TPa | b = c = 2.60 | 2d |

| Ref. [13] | α = β = y =90 | |

| (192) P6/mcc | a = 3.68 | 2a |

| .00 TPa | b = c = 2.65 | 12l |

| Ref. [15] | α = β = 90 | x = 0.1097 |

| y = 120 | y = 0.6831 | |

| (223) |

a = 2.59 | 2a |

| 15 TPa | α = β = y =90 | 6d |

| Ref. [13] | ||

| .00 TPa | a = 2.44 | 2a |

| Ref. [15] | α = β = y =90 | 6c |

3.1 Structural search process

In total, nearly 30000 fluorine structures with 2-16 atoms per unit cell spanning the pressure range of 1 to 5 TPa were generated in 40 different runs, via USPEX combined with DFT, using the Quantum ESPRESSO suite. As explained earlier, the first generation of each run consists of randomly generated structures. After that, the act of creating a new candidate structure usually follows a two-step procedure. First, the evolutionary algorithm enables the generation of a new system using one of three operations [17, 18, 19, 20]:

• Heredity combines two or more parent structures to create a new one, allowing a broad search of the energy landscape while preserving fragments of good structures.

• Permutation randomly swaps chosen pairs of atoms within the unit cell, which facilitates finding the optimal ordering of the atoms.

• Mutation creates a child structure from a single parent, retaining some characteristics from it while introducing new structural features. There are two main types of mutations: lattice mutation, that randomly distorts the cell shape, allowing a better exploration of the neighborhood of parent structures and preventing premature convergence of the lattice; and soft-mutation, which moves the atoms along the eigenvectors of the softest modes in order to create a new structure across the lowest energy barrier, allowing a local and semi-local exploration of the energy landscape.

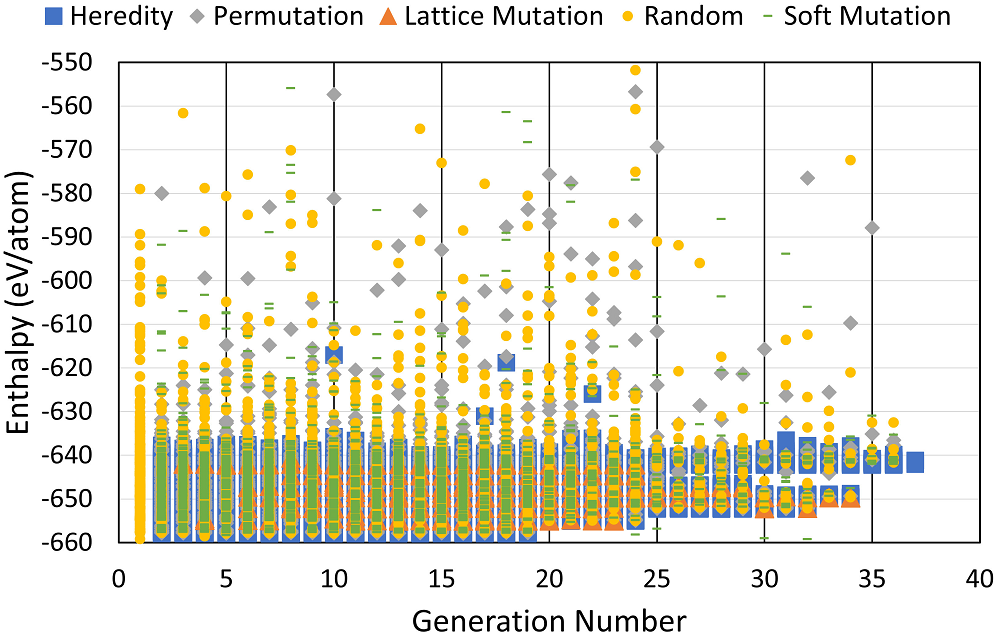

Each run contemplates the use of the genetic operations described above, together with a percentage of randomly generated structures. Figure 1 shows the enthalpy distribution of the generated systems within all 40 runs performed. We can see that randomly generated structures (yellow circles) with those from permutation operations (grey rhombus) and up to some extent also the ones from soft mutation (green dashes) span a large energy interval. In contrast, most relevant structures are created due to heredity (blue squares) and lattice mutation (orange triangles).

Figure 1 Enthalpy distribution, in eV per atom, of structures generated during 40 different runs for fluorine with 2-16 atoms per unit cell and at 1-5 TPa. The symbols represent the origin of generated structures: random generation (yellow circles) or as a result of certain genetic operations: heredity (blue squares), permutation (grey rhombus), lattice mutation (orange triangles), and soft mutation (green dash).

3.2 Crystal structure determination

From USPEX predictions, 14 different crystal structures emerged as potential candidates for fluorine in the terapascal regime. These structures included all those previously reported that were compatible with our cell sizes (i.e., except for

Table II K-point grids for the final phases of high-pressure fluorine.

| Phase | k-point grid |

|---|---|

| (12) C2/m - 2 | 16 × 16 ×12 |

| (71) Immm - 2 | 16 × 16 ×12 |

| (139) I4/mmm - 2 | 12 × 16 ×16 |

| (225) |

12 × 12 ×12 |

| (12) C2/m - 6 | 12 × 16 ×12 |

| (15) C2/c - 8 | 4 × 4 ×4 |

| (64) Cmca -8 | 16 × 16 × 16 |

| (131) P42/mmc | 16 × 16 ×16 |

| (223) |

16 × 16 ×12 |

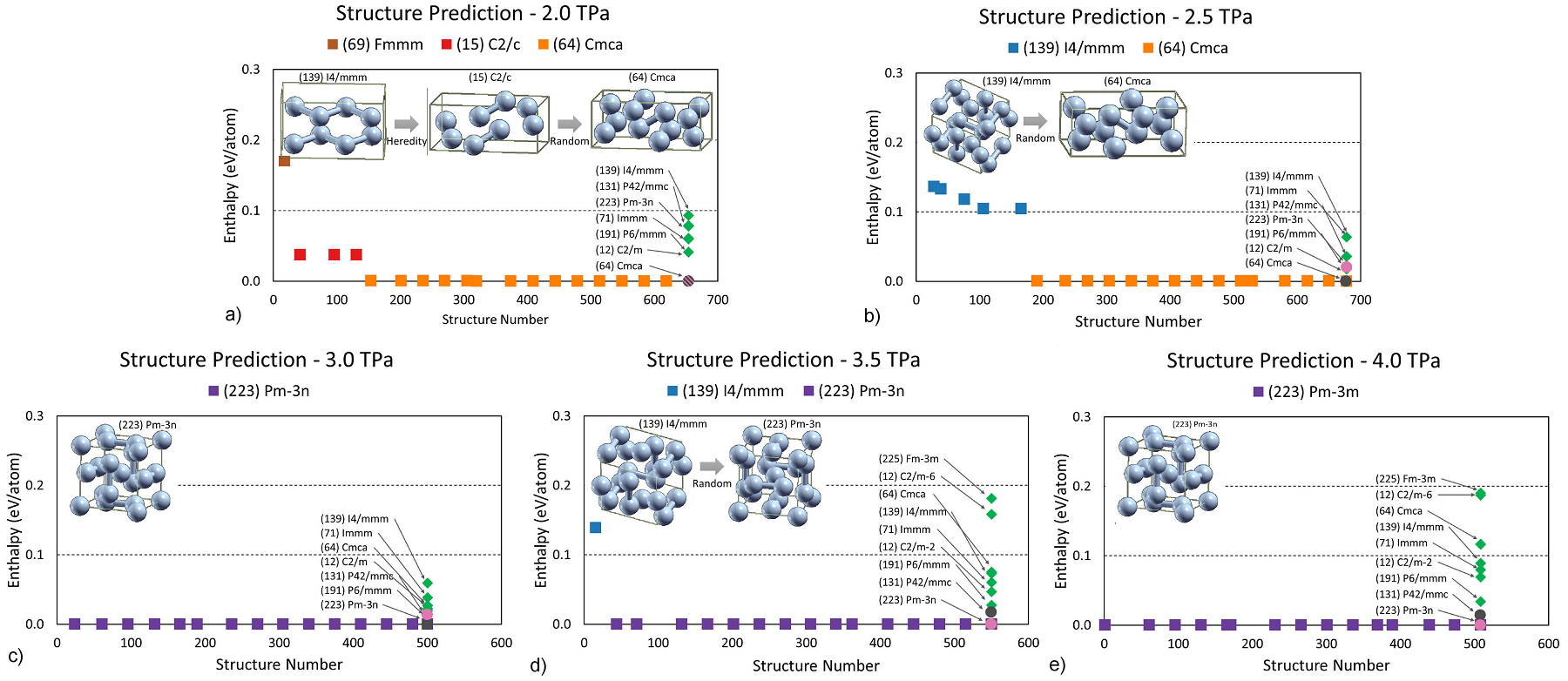

Figure 2 shows the case of 8 atoms per cell at selected pressures after variable-cell optimization from ab initio results for the forces and cell stresses. USPEX was able to predict those phases proposed in previous works [13,

15] after just a few iterations. The insets show structures with the best individual enthalpy per atom at each generation; the squares mark the minimum enthalpy corresponding to different space groups:

Figure 2 Structure prediction process for fluorine with 8 atoms per cell within the pressure range from 2.0 to 4.0 TPa. The squares show the lowest enthalpy obtained at a given generation, with the colors indicating the space group of the best individuals:

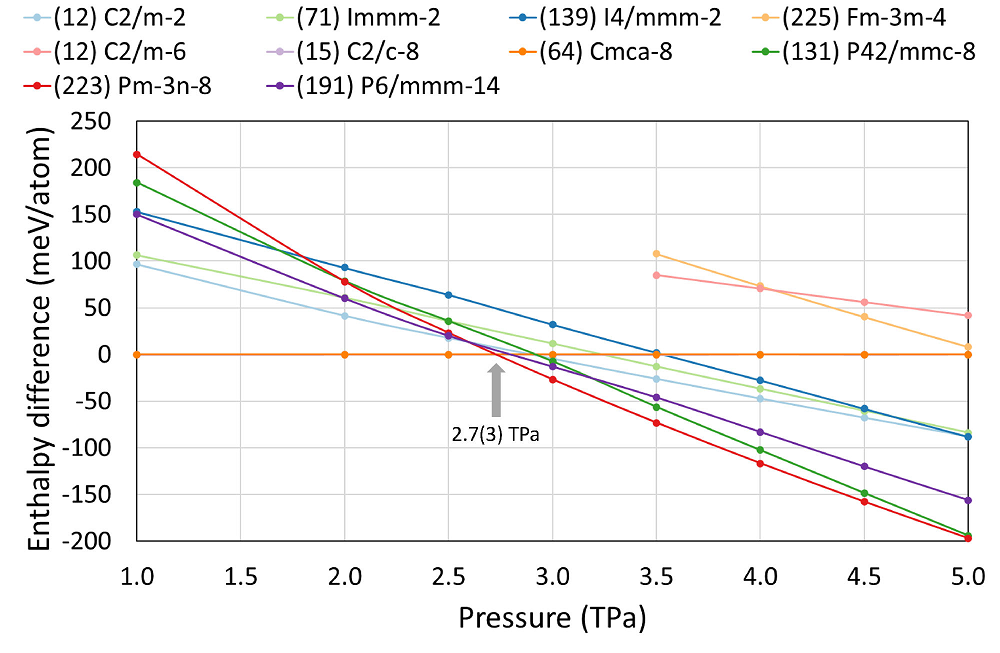

Figure 3, the enthalpy relations for the structures found in this work, along with those previously proposed, are represented. The molecular phase Cmca remains stable up to 2.7(3) TPa. This persistence of the phase Cmca up to the terapascal regime was also reported in Ref. [15], and our USPEX calculations confirm that statement. Cmca transforms directly into

Figure 3 Enthalpy relations of the structures found with the USPEX code and those reported in Refs. [13,

15], relative to the

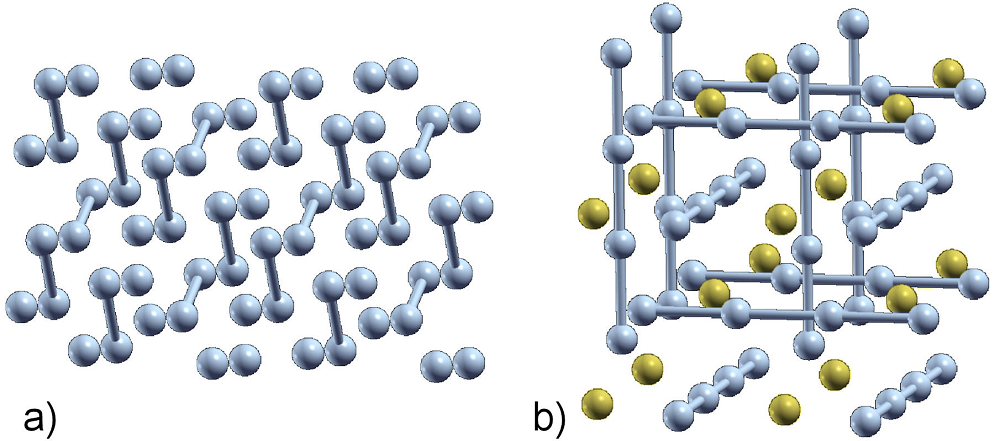

Regarding the two most stable structures found in this work, we can conclude that Cmca is a molecular phase, since, for example at 1.0 TPa, the nearest F-F distance is calculated as 1.28 Å, and the second nearest F-F distance is 1.55 Å, which clearly establishes the molecular character of this crystalline structure which is shown in Fig. 4a). On the other hand, the phase

Figure 4 Fluorine primitive cell of a) molecular Cmca at 1.0 TPa, and b) polymeric-atomic

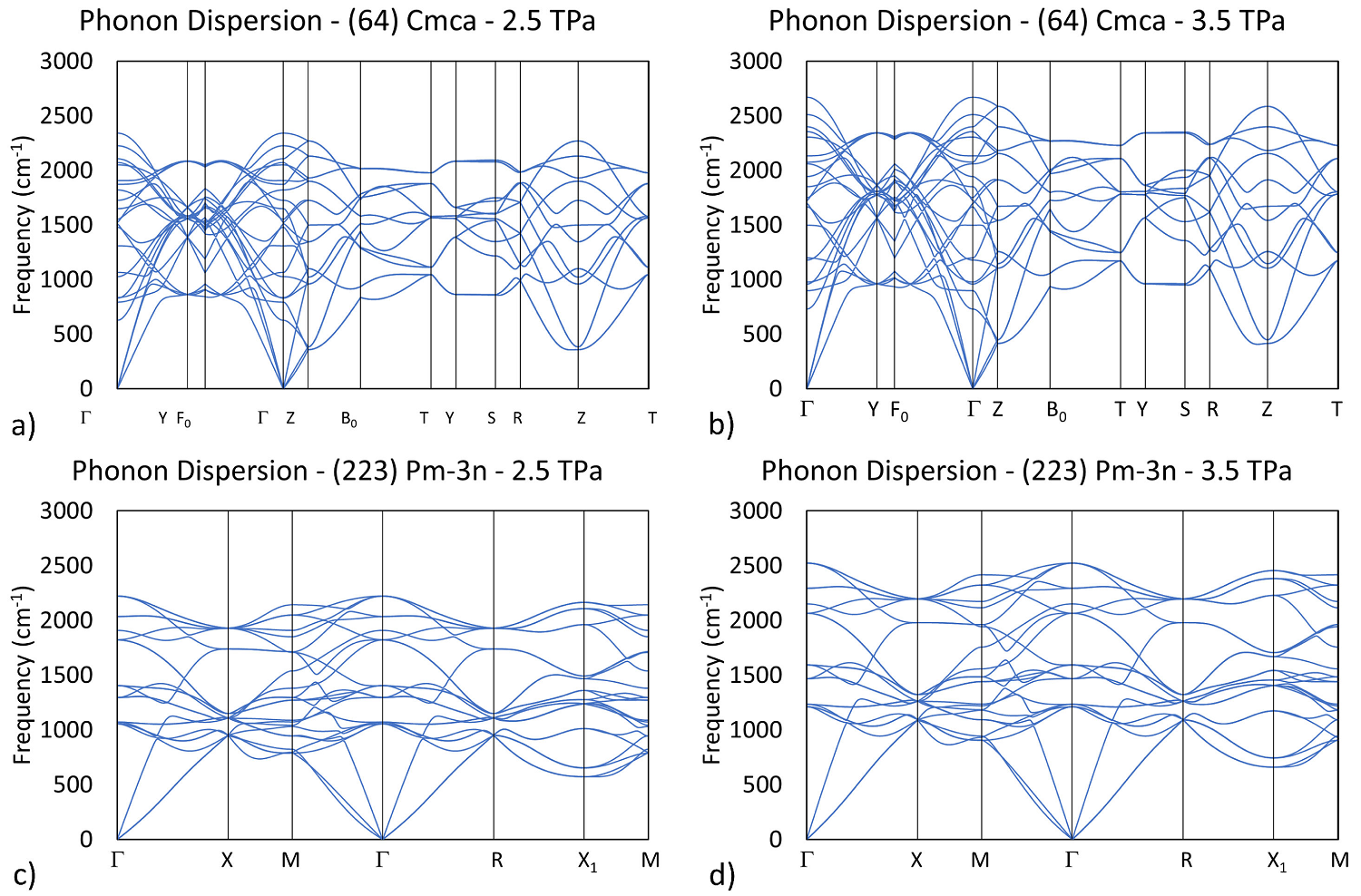

The dynamical stability of structures Cmca and

Figure 5 Phonon dispersion relations of Cmca at a) 2.5 TPa and b) 3.5 TPa, and

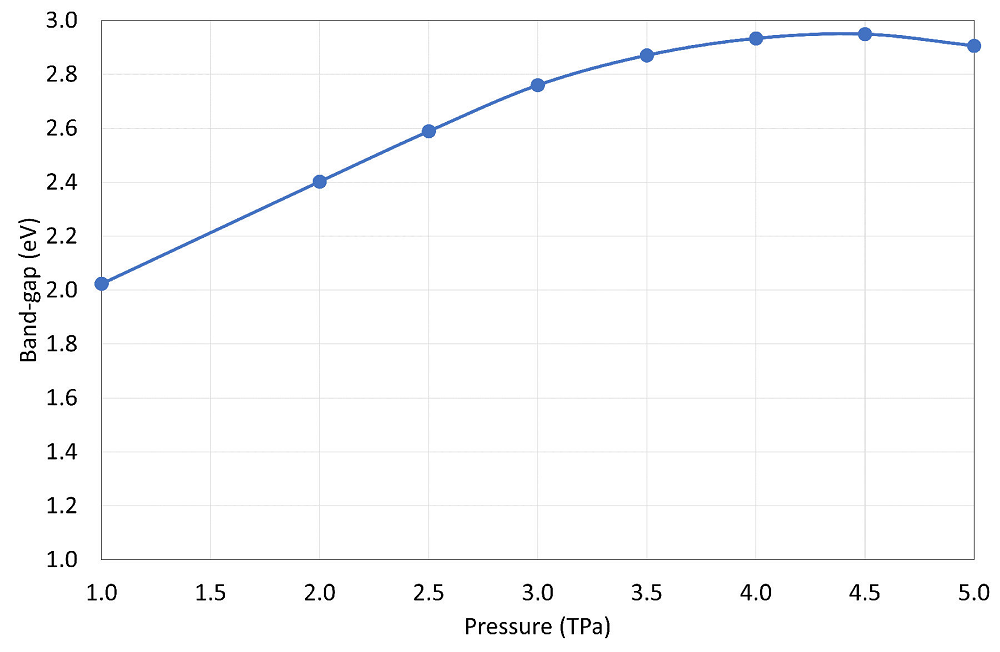

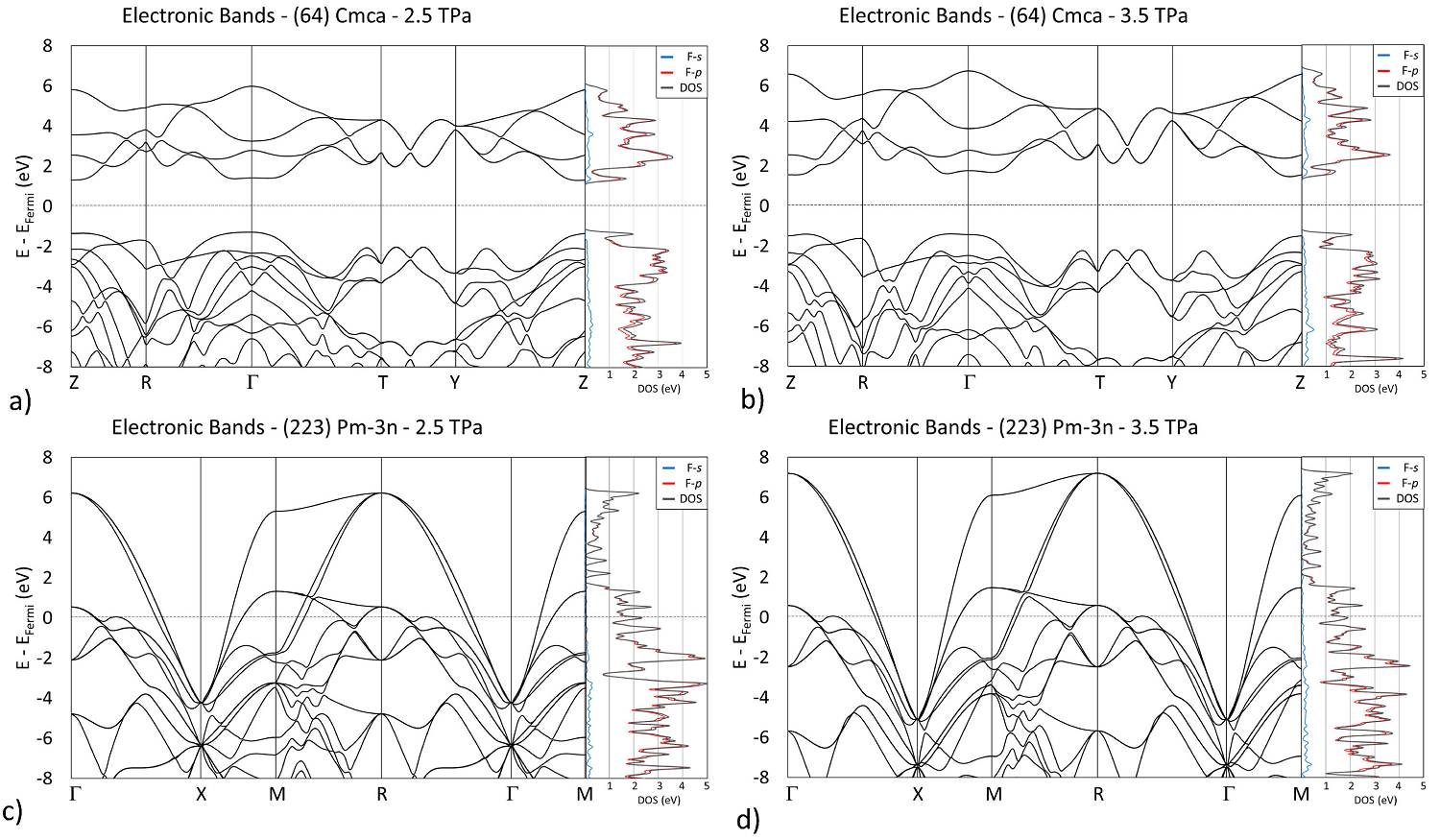

In addition to the phonon calculations, electronic band structures were also computed on both systems. At pressures below and above the transition, phase

Figure 6 Band structure and partial density of states (PDOS) of Cmca at (a) 2.5 TPa and (b) 3.5 TPa, and

4 Conclusions

In summary, the evolutionary structural search approach implemented in the USPEX code, supported by DFT for calculating forces and stresses, has been tested at pressure conditions spanning several TPa. We corroborated the existence of a transition from the widely stable Cmca molecular form of fluorine towards a non-molecular phase that is composed of a mixture of linear chains and isolated atoms. So far, the stability of a pure element’s molecular solid is one of the highest in fluorine, rivaled only by oxygen that also shares with fluorine its high electronegativity, confirming the heuristic expectation that these two elements should behave similarly in many ways, among which, being reluctant to become fully polymeric. In fact, an increase in phonon frequencies for Cmca shows that its molecular structure seems to get hardened and more dynamically stable upon compression, at least up to 4.5 TPa when a decrease in its electronic band-gap starts appearing. Previous contradictory reports of intermediate stable phases existing in the transition between Cmca and

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)