INTRODUCTION

Adolescents are more vulnerable to depression, psychoses, and suicidal thoughts (Avanci, Assis, Oliveira, Ferreira, & Pesce, 2007), which motivates research on mental health during youth. A previous study observed that 13.4% of children and adolescents have some mental disorder (Polanczyk, Salum, Sugaya, Caye, & Rohde, 2015), constituting a fact that can influence behaviours, including suicidal ideation, which is the presence of thoughts and ideas of engaging in action to kill oneself (Baiden & Tadeo, 2020). Suicidal ideation is one of the risk factors associated with suicide attempts (Victor & Klonsky, 2014). The suicide rates of young people between 10 and 24 years can range from 2.9% to 5.4%, depending on the region, knowing that these rates could be higher if underreporting did not occur (Machado & Santos, 2015).

Recent research indicates the existence of a positive relationship between physical activity and mental health (Pascoe et al., 2020), placing physical activity as a possible protective factor against mental health problems in adolescents (Guo, Tomson, Keller, & Söderqvist, 2018; Lourenço, Peres, Porto, Oliveira, & Dutra, 2017). However, research erroneously encompasses physical activity, exercises, and sports in the same category (Bezerra, Lopes, Del Duca, Barbosa Filho, & Barros, 2016; Pinheiro, Andrade, & De Micheli, 2016), and such habits have distinct characteristics.

Evaluating studies related to sports practice indicates that adolescents who practice sports have better mental health indicators (Badura, Geckova, Sigmundova, van Dijk, & Reijneveld, 2015) and are less likely to suffer from depression, suicidal ideation (Babiss & Gangwisch, 2009), and anxiety (Graupensperger, Sutcliffe, & Vella, 2021). In addition, adolescents involved in sports during elementary and high school were less likely to report suicidal ideation during high school when compared to those who never participated in sports (Taliaferro, Eisenberg, Johnson, Nelson, & Neumark-Sztainer, 2011). However, it is noteworthy that the type of sports practice (team or individual) can interfere with mental health outcomes. In the study by Pluhar et al. (2019), the report of anxiety and depression was higher in individual sports athletes and among athletes of the female sex than in team sports athletes. Team sports practitioners also had lower rates of suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts (Harrison & Narayan, 2003).

However, still be slightly explored differences between group and individual sports in the literature (Panza et al., 2020; Taliaferro et al., 2011). According to a recent systematic review of 29 studies involving sports participation in adolescents and symptoms of anxiety or depression, of which only seven categorized the sport as team and individual (Panza et al., 2020), even though their different internal and external characteristics are evident, such as planning, interaction, techniques, tactics, and psychological issues (Dantas, 2014). Thus, it is still unclear how group and individual sports relate to mental health and suicidal ideation (Panza et al., 2020).

Mental health is multifactorial and may be associated with factors such as gender, age (Lopes et al., 2016), socioeconomic status (Jansen et al., 2011), and family relationships (Benetti, Pizetta, Schwartz, Hass, & Melo, 2010). Thus, this study aimed to analysed the association between different types of physical activity (systematized exercise, individual, and collective sports), mental health, and suicidal ideation in adolescents.

METHOD

Design of the study

We performed a cross-sectional study in the city of Caruaru, in the State of Pernambuco (Northeastern Brazil), and followed the guidelines of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) standardized reporting guidelines for cross-sectional studies for this study (von Elm et al., 2008).

Description of the sample

The target population was limited to high school adolescents (14 to 18 years) from public schools, which cover around 80% of students in the city. The total population was 9,604 youth distributed across 15 schools. We estimated the sample considering a 95% confidence interval, a maximum tolerable error of 5 percentage points, 1.5 effects of design, and defined the estimated prevalence at 50%. In addition, the sample size was increased by 20% to minimize the losses in applying incomplete questionnaires. In this sense, the minimum sample would be 653 adolescents.

We balance the population sample regarding school class and the period of the day that students attended school. We divided the classes into three high school years: first, second, and third. In addition, we divided the studentsʼ school time into morning, afternoon, and night shifts. A two-stage cluster sampling procedure was performed to select the required sample. In the first stage, there was the stratification of schools by size. In the second stage, there was stratification by shifts. We performed the selection by generating random numbers through Sample XS software (World Health Organization, n.d.), and the class was the sampling unit for the final stage of the process.

Measurements

The dependent study variables were the mental health indicators, evaluated through the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), previously validated for assessment of children and adolescents (Goodman, 1999), and with good reproducibility indicators in Brazil (Saur & Loureiro, 2012). The questionnaire consists of 25 items. The Total score is categorized into Normal difficulties (0-15), Borderline (16-19), and Abnormal (20-40).

We also used the Self-Reporting Questionnaire (SRQ-20), validated in a Brazilian population, to identify possible psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety, commonly called common mental disorders (de Jesus Mari & Williams, 1986). These conditions correspond to 90% of the total morbidity caused by psychiatric disorders. The questionnaire provides a score of 0 to 20 points, and the best cut-off scores seem to be greater than or equal to seven, being the same for women and men. Therefore, in this survey, the adolescents with scores greater than or equal to seven were classified as “exposed” with the most excellent chance of having some common mental disorder and less than seven as “unexposed” (de Jesus Mari & Williams, 1986).

We obtained the suicidal ideation through the questions: “during the past 12 months, have you ever seriously thought about attempting suicide?” with Yes or No answers (Babiss & Gangwisch, 2009; O’Connor & Nock, 2014). The SRQ used already contains the question: “Have you had the idea of ending your life?”. However, to evaluate the current reality, more appropriate for the studyʼs cross-sectional design, the question was added to the questionnaire considering the last 12 months. This question was used in a previous study with 14,594 adolescents aged 11 to 21 (Babiss & Gangwisch, 2009).

The forms of leisure-time physical activity were obtained from the question “Do you regularly perform some physical activity in your free time, such as exercise, sports, dance, or martial arts?” categorized into does not exercise, practice exercise, or practice sports (individual or team). In addition, during the questionnaire, adolescents who practiced more than one physical activity were asked to inform their preferred activity and that they performed for a longer time, which was considered in the analysis.

Adolescents answered an adapted version of the Global School-based Student Health Survey (GSHS). In addition, we recorded gender, age, ethnicity (white and non-white), place of residence (urban and rural), occupation (working and not working), family income (minimum wage), and maternal education (equal to or greater than eight years of study and greater than eight years of study) as sociodemographic data.

The relationship of young people between classmates and parents was evaluated through the questions: “As for your relationship with your classmates and friends, you are:”, “As for your relationship with your parents, you are:” and “As for your relationship with your teachers, you are:”, respectively, using a Likert scale is organized into three categories: dissatisfied (very dissatisfied and dissatisfied), indifferent, and satisfied (satisfied and very satisfied).

The reproducibility indicators presented moderate to ahigh intraclass correlation coefficient, with coefficients of agreement (Kappa index) of .78 for symptoms of common mental disorders; .62 for mental health difficulties; .82 for suicidal ideation; .77 for a relationship with parents; and .79 for a relationship with friends.

Procedure

We applied questionnaires between September and November 2017.They were applied in the classroom in the form of a collective interview without the presence of teachers. Five researchers (two professors and three undergraduate students) continuously assisted the students in clarifying doubts when filling out the forms questionnaires. We excluded the questionnaires answered by students under 14 and over 19 years old after application.

Statistical analysis

We performed the Data entry using the Epi Data program version 3.1 (EpiData Software, n.d.) and did the electronic data control using the ʻCHECKʼ function. The data entry was repeated, and errors that were detected by the same file comparison function were corrected.

All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software program (SPSS/PASW version 20; IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Categorical variables were summarized as relative frequency. In addition, crude and multivariate regression/models were conducted to analyze the association between different forms of physical activity (exercises, team, or individual sports), mental health, and suicidal ideation in adolescents. In the multivariate regression/models, the confusion variables were all entered simultaneously using the “Enter” with the criteria for entry using p < .20 (by the Chi-squared test) and the criteria to remain in the final model using (p < .05).

Tests for interaction effects were also performed between gender, mental health, and different forms of leisure time and physical activity. We decided to stratify the sample by gender to perform the analyses and show results as crude and adjusted odds ratio (OR) values and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The Hosmer-Leme show test was used to assess the model goodness-of-fit.

Ethical considerations

This study followed the determinations of the National Health Council and received approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Centro Universitário Tabosa de Almeida (Asces-Unita) number: (CAAE-80759417.3.0000.5203/CEP-ASCES: 2.492.751).

We invited all students in the selected classes to participate in the study, regardless of age, and obtained the informed consent of all participants. In addition, the parents or guardians of the adolescents were invited to sign a consent form; with the consent signed by the guardian, the adolescent interested in participating also signed a term declaring their agreement to participate in the research.

RESULTS

We examined 687 adolescents from 20 classes (10 in the morning, 05 in the afternoon, and 05 in the night shifts). However, 14 parents refused the invitation, and we excluded seven questionnaires from students under 14 and over 19 years old. Thus, the final sample included 666 adolescents. Table 1 presents the demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the sample. It is noteworthy that some study variables have a lower amount than the final sample because, concerning their ethical rights, some students chose not to answer some questions in the questionnaire, which were classified in this research as missing.

Table 1 Study participants’ demographic and socioeconomic characteristics in adolescents

|

Boys

318 (52.3) |

Girls

348 (47.7) |

Total

666 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | n | % | n | % | n | % | p-value | ||

| Age group (years old) | |||||||||

| 14 – 15 | 52 | 16.4 | 45 | 12.9 | 97 | 14.6 | .017 | ||

| 16 – 17 | 175 | 55.0 | 229 | 65.8 | 404 | 60.7 | |||

| 18 – 19 | 91 | 28.6 | 74 | 21.3 | 165 | 24.8 | |||

| Occupation | |||||||||

| Work | 138 | 44.8 | 107 | 31.0 | 245 | 37.5 | < .001 | ||

| Not work | 170 | 55.2 | 238 | 69.0 | 408 | 62.5 | |||

| Place of residence | |||||||||

| Urban | 271 | 85.5 | 266 | 77.8 | 537 | 81.5 | .011 | ||

| Rural | 46 | 14.5 | 76 | 22.2 | 122 | 18.5 | |||

| Educational level of mother | |||||||||

| > 8 years of study | 33 | 11.9 | 24 | 5.9 | 57 | 9.7 | .099 | ||

| ≤ 8 years of study | 245 | 88.1 | 383 | 94.1 | 528 | 90.3 | |||

| Family income (minimum wage) | |||||||||

| < 1 | 38 | 14.7 | 65 | 24.2 | 103 | 19.5 | < .001 | ||

| 1 – 3 | 170 | 65.6 | 186 | 69.1 | 356 | 67.4 | |||

| > 3 | 51 | 19.7 | 18 | 6.7 | 69 | 13.1 | |||

| Relationship with friends | |||||||||

| Satisfied | 250 | 79.1 | 273 | 79.4 | 523 | 79.2 | .938 | ||

| Unsatisfied | 66 | 20.9 | 71 | 20.6 | 137 | 20.8 | |||

| Relationship with parents | |||||||||

| Satisfied | 254 | 80.4 | 272 | 78.6 | 526 | 79.5 | .574 | ||

| Unsatisfied | 62 | 19.6 | 74 | 21.4 | 136 | 20.5 | |||

| Symptoms of common mental disorders |

|||||||||

| More probability | 214 | 67.5 | 159 | 45.8 | 373 | 56.2 | < .001 | ||

| Less probability | 103 | 32.5 | 188 | 54.2 | 291 | 43.8 | |||

| Mental health difficulties | |||||||||

| Normal or borderline | 164 | 51.6 | 71 | 20.4 | 235 | 35.3 | < .001 | ||

| Abnormal | 154 | 48.4 | 277 | 79.6 | 431 | 64.7 | |||

| Suicidal ideation | |||||||||

| No | 280 | 88.6 | 266 | 77.1 | 546 | 82.6 | < .001 | ||

| Yes | 36 | 11.4 | 79 | 22.9 | 115 | 17.4 | |||

| Leisure-Time Physical Activity | |||||||||

| Do not practice | 85 | 26.8 | 155 | 44.5 | 240 | 36.1 | < .001 | ||

| Practice exercise | 84 | 26.5 | 157 | 45.1 | 241 | 36.2 | |||

| Practice individual sports | 18 | 5.7 | 8 | 2.3 | 26 | 3.9 | |||

| Practice team sports | 130 | 41.0 | 28 | 8.0 | 158 | 23.8 | |||

Higher prevalence was observed related to mental disorders (54.2% vs. 32.5%), difficulties related to mental health (79.6% vs. 48.4%), and suicidal thoughts (22.9% vs. 11.4%) in girls than in boys (p < .001 for all; Table 1).

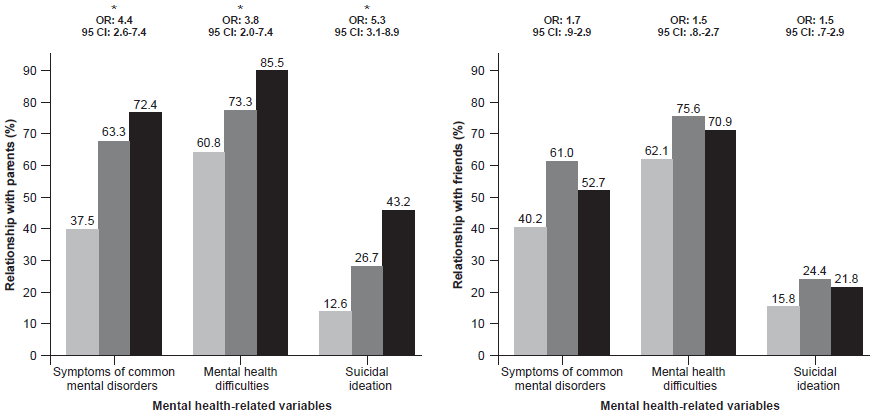

There was a strong association between good relationships with parents and variables related to mental health (mental health difficulties, symptoms of common mental disorders, and suicidal ideation; Figure 1). In addition, it was noted that young people who reported being dissatisfied with their relationship with their parents were more likely to have common mental disorders (OR = 4.4; 95% CI = [2.6, 7.4]), mental health-related difficulties (OR = 3.8; 95% CI = [2.0, 7.4]), and to have suicidal thoughts (OR = 5.3; 95% CI = [3.1, 8.9]) when compared those who reported being satisfied with the relationship with their parents, showing themselves as an essential control variable (Figure 1).We did not find a significant association between the relationship with friends and the variables related to mental health.

Figure 1 Prevalence of the satisfaction index of relationships with parents and friends and their associations with the common mental disorder, mental health, and suicidal ideation of adolescents.OR. Odds ratio; 95 CI: Confifence interval 95%; * p < .001.

The need for stratification by gender was verified after testing the interaction. Thus, we observed that boys who practiced team sports were less likely to have common mental disorders (OR = .41; 95% CI = [.20, .85]) and suicidal ideation (OR = .26; 95% CI = [.09, -.72]) after adjusting for potential confounding factors (Table 2). On the other hand, we did not find a significant association between leisure-time physical activities and mental health-related problems in the girls (Table 2).

Table 2 Association between physical activity in leisure and mental health indicators in adolescents stratified by sex

| Variables |

OR

Crude |

95 CI | p |

p

overall |

OR

Adjusted |

95 CI | p |

p

overall |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girls | |||||||||

| Leisure-Time Physical Activity | Symptoms of common mental disorders | ||||||||

| Do not practice | 1 | .154 | 1 | .191 | |||||

| Practice exercise | 1.38 | .88-2.16 | .157 | 1.32 | .78-2.25 | .304 | |||

| Practice individual sports | .61 | .14-2.63 | .505 | .65 | .13-3.22 | .597 | |||

| Practice team sports | 1.82 | .79-4.20 | .158 | 2.20 | .77-6.29 | .141 | |||

| Leisure-Time Physical Activity | Mental health difficulties | ||||||||

| Do not practice | 1 | .384 | 1 | .845 | |||||

| Practice exercise | .86 | .49-1.51 | .609 | 1.25 | .65-2.40 | .509 | |||

| Practice individual sports | .69 | .13-3.60 | .660 | .62 | .11-3.51 | .585 | |||

| Practice team sports | .69 | .27-1.78 | .443 | 1.08 | .32-3.61 | .900 | |||

| Leisure-Time Physical Activity | Suicidal ideation | ||||||||

| Do not practice | 1 | .954 | 1 | .508 | |||||

| Practice exercise | 1.01 | .59-1.71 | .966 | 1.04 | .55-1.95 | .907 | |||

| Practice individual sports | .48 | .06-4.05 | .501 | .47 | .05-4.30 | .504 | |||

| Practice team sports | 1.12 | .44-2.86 | .807 | 1.68 | .58-4.84 | .335 | |||

| Boys | |||||||||

| Leisure-Time Physical Activity | Symptoms of common mental disorders | ||||||||

| Do not practice | 1 | .009 | 1 | .030 | |||||

| Practice exercise | .61 | .32-1.15 | .125 | .64 | .30-1.32 | .231 | |||

| Practice individual sports | 1.70 | .61-4.74 | .309 | 1.50 | .46-4.92 | .503 | |||

| Practice team sports | .41 | .23-0.75 | .003 | .41 | .20-0.85 | .016 | |||

| Leisure-Time Physical Activity | Mental health difficulties | ||||||||

| Do not practice | 1 | < .001 | 1 | .055 | |||||

| Practice exercise | .58 | .31-1.06 | .078 | .54 | .27-1.06 | .073 | |||

| Practice individual sports | 1.10 | .39-3.12 | .858 | .99 | .32-3.13 | .996 | |||

| Practice team sports | .49 | .28-0.87 | .014 | .48 | .26-0.91 | .023 | |||

| Leisure-Time Physical Activity | Suicidal ideation | ||||||||

| Do not practice | 1 | .013 | 1 | .020 | |||||

| Practice exercise | .45 | .18-1.13 | .088 | .55 | .21-1.44 | .221 | |||

| Practice individual sports | 1.21 | .35-4.19 | .758 | 1.55 | .42-5.74 | .514 | |||

| Practice team sports | .28 | .11-0.68 | .005 | .26 | .09-0.72 | .010 | |||

Notes: OR: Odds ratio. 95 CI: Confidence interval 95%

# Adjusted for age, family income, relationship with friends and parents.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The main results of this study were: a) good relationship with parents minimizes the chances of adolescents having mental health-related problems; b) higher prevalence was observed related to mental disorders, difficulties related to mental health, and suicidal thoughts in girls; c) the practice of team sports was associated with fewer symptoms of common mental disorders, lower mental health problems, and less suicidal ideation only among boys, independently of age, family income, relationship with parents, and relationships with friends.

We noted that adolescents with a good relationship with their parents had fewer mental health problems. Reinforcing this finding, a study conducted with 658 students aged between 14 and 17 years found that young people were less exposed to risky behaviours when parents were aware of their children’s habits and placed limits and rules on them (Wang, 2013). Thus, good relationships with parents can curb common aggressive or sexual impulses of adolescence, behaviours that can correlate with mental health problems and a good relationship with parents improves well-being and health (Fonseca, 1997).

In the present study, we found that girls are more vulnerable to problems related to mental health. Similarly, Saud and Tonelotto (2005) observed that girls experience more emotional problems, which may reflect the characteristics of the cultural environment in which they are inserted. In addition, it has been seen that early pubertal time in girls can have an impact on mental health, as found in a study that accompanied 7802 American girls, noting that those who had earlier menarche presented the beginning of adulthood in psychopathology, even after considering the demographic and contextual variables commonly associated with vulnerability to mental health (Mendle, Ryan, & McKone, 2018). In this sense, we found evidence that the puberty time of girls is an essential factor related to mental health and thereby can partly explain this greater vulnerability compared to boys.

Curiously, we observed that only team sports were associated with fewer psychiatric symptoms in the practice of leisure-time physical activity. Previous studies have shown that physical activity can prevent mental problems. For example, an 11-year prospective follow-up study with nearly 34,000 volunteers, using univariate and multivariate logistic regression, demonstrated that regular physical activity, regardless of intensity, appeared to prevent depression but not anxiety disorders (Harvey et al., 2018). Also, a meta-analysis of 49 prospective studies showed that physical activity protects against the onset of depression, regardless of age and region (Schuch et al., 2018). Moreover, it emphasizes that sports have peculiar characteristics which go beyond exercise. Sports have, in their essence, discipline, the development of competencies, behaviors, attitudes, and values (Eagleton, McKelvie, & de Man, 2007). When such values are added to group work, this practice helps directly in maturing and favors the development of mental health, as shown in studies where observed that the participation of children and adolescents in team sports is associated with better psychological health than individual sports (Eime, Young, Harvey, Charity, & Payne, 2013; Pluhar et al., 2019).

Unlike individual sports, the game actions in team sports are always performed in direct cooperation with teammates, with varied environments and tactical-strategic aspects (Oliveira & Tavares, 1996).Thus, team sports help develop the collective spirit, stimulate social interaction, develop reasoning and intelligence, and help in discipline as generated by respect for rules, opponents, and their companions (Rose Júnior, 2006).

Interestingly, the relationship between team sports with mental health and suicidal ideation was only observed among boys. Such a point may be related to motivational factors since the present competitiveness in sports is more valued by boys (Kopcakova et al., 2015). In addition, boys deal with the conflicts which commonly occur during sports practice more naturally than girls, and the possible provocations related to the appearance or incoordination which can occur during such practice can make girls feel bad, and consequently, they have a repulsion to the sport (Weiss & Smith, 2002).

The main limitation of this study was the cross-sectional design, and the correlative nature of the data precluded us from establishing a causal relationship between leisure-time physical activity and mental health. Also, we did not control the time of practice of the activity performed by adolescents because the questionnaire does not evaluate this point, but so far it is not known whether the variables respond differently to depend on the time of practice. In this sense, we speculate, given the scarcity of the literature, that the time of practice may be important to evaluate the chronic effects of physical exercise and sports practices on mental health-related variables. However, even aware of the limitation of the cross-sectional design of the present study, our result drives us to think that socialization related to practice seems to have a more significant impact on mental health (Andersen, Ottesen, & Thing, 2019; Eime et al., 2013) and not physiological changes, changes usually associated with the time of practice. In this sense, it would be interesting for future studies to make adaptations in the questionnaires to assess whether the time of practice can affect adolescentsʼ mental health. Finally, it should be considered that presenting symptoms of mental disorders does not necessarily imply that there is a psychiatric diagnosis to be treated.

The representative sample can be pointed to as one of the strengths of this study since the sampling procedures were established to ensure that the population was composed of adolescent students attending schools in different shifts. In addition, we evaluated different forms of practice of physical activities (exercises, team, or individual sports) and their impact on mental health after adjusting for potential confounding variables.

In conclusion, we observed a higher prevalence of mental disorders, difficulties related to mental health and suicidal thoughts in girls. Among the different forms of physical activity (exercises, team, or individual sports), only the practice of team sports was associated with fewer symptoms of common mental disorders, lower mental health problems, and less suicidal ideation, however, only among boys.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)