Systematic

Spatial and phylogenetic distribution of the genera of the Heliantheae tribe (Asteraceae) in Mexico

Morales-Garduño, Luis12*

http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5044-1726

http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5044-1726

Villaseñor, José Luis2

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0781-8548

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0781-8548

http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5044-1726

http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5044-1726Villaseñor, José Luis2

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0781-8548

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0781-8548-

Publication dates-

September 09, 2025

Jul-Sep , 2025

- Article in PDF

- Article in XML

- Automatic translation

- Send this article by e-mail

- Share this article +

Abstract

Background:

Biodiversity is described considering its alpha (local taxon richness), beta (difference of taxa between localities), or gamma (regional richness) components. We assessed the alpha component using different facets, taxonomic and phylogenetic. In Mexico, more than half of the genera of the Heliantheae tribe are included in a phylogeny, and a taxonomically curated geographic database is available, facilitating their study under these concepts.

Question:

Where is the greatest alpha diversity of Heliantheae genera concentrated in Mexico from a taxonomic and phylogenetic perspective?

Data description:

Geographic data of 75 genera of Heliantheae in Mexico (gamma diversity) and phylogeny including 45 Mexican genera.

Study site:

Mexico, divided into a grid of 253 cells 1° of latitude and longitude.

Methods:

We analyzed 22,166 records for Heliantheae to determine alpha taxonomic richness and weighted endemism. Phylogenetic diversity and endemism were evaluated using 13,251 records from 45 genera included in the molecular data phylogeny obtained with U.PhyloMaker. We analyzed and performed maps using Biodiverse and QGIS programs.

Results:

Twenty cells with high alpha diversity values were identified, 11 placed in the Mexican mountainous regions and nine in the arid or semiarid areas. A high correlation exists between alpha taxonomic and phylogenetic diversity.

Conclusions:

Including missing taxa in phylogeny could change the biogeographic patterns of taxonomic and phylogenetic endemism. All indices are necessary to select priority areas for the conservation of the tribe and associated biodiversity.

Keywords::

alpha diversity, arid zones, endemism, mountains, Neotropics

We commonly analyze biological diversity by considering all or some of its components. For example, the alpha component determines local species richness, the beta component determines species differences between localities, and the gamma component determines species richness in an entire region (Whittaker 1972). They help us to detect spatial distribution patterns at different geographic scales using different quantitative techniques, such as data matrices that record and rank data on the incidence or abundance of taxa in a geographic environment. We then apply indices or estimators of these matrices, which are statistics that help measure or compare diversity between different sites. Then, the similarity or dissimilarity between sites is assessed and visualized using cluster analysis or other alternative multivariate methods (Murguía-Romero & Rojas 2001, Tuomisto 2010, Rodríguez et al. 2017).

-

Whittaker 1972Evolution and measurement of species diversityTaxon, 1972

-

Murguía-Romero & Rojas 2001Biogeografía cuantitativaIntroducción a la Biogeografía en Latinoamérica: Teorías, Conceptos, Métodos y Aplicaciones, 2001

-

Tuomisto 2010A consistent terminology for quantifying species diversity? Yes, it does existOecologia, 2010

-

Rodríguez et al. 2017La macroecología en México: historia, avances y perspectivasRevista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 2017

Knowing how living beings are distributed geographically is crucial to identifying areas rich in taxa (high taxonomic diversity) or lineages (high phylogenetic diversity). Both facets of biodiversity allow its study from the weighting of its alpha component (taxonomic alpha or phylogenetic alpha), which helps a better understanding of biogeographic patterns or to make decisions about the selection of priority sites for its conservation (Whittaker 1972, Brooks et al. 2006, Jarzyna & Jetz 2016, Mishler 2023). Among the different metrics that allow understanding of taxonomic alpha diversity is the richness of taxa present in a site (Richness or Taxonomic richness, TR), which is equal to the number of taxa in each site (González-Orozco et al. 2011); another is weighted endemism (WE), which is the sum of the reciprocal of the total number of areas in which each taxa occurs (Crisp et al. 2001). In contrast, phylogenetic alpha diversity can be measured by its phylogenetic diversity (PD), obtained by summing the lengths of the branches of a phylogeny (Faith 1992) or through its phylogenetic endemism (PE), where each branch of a phylogenetic tree is weighted by the inverse of the size of the total range of the clade (Rosauer et al. 2009). Furthermore, recognizing sites with high alpha biodiversity (taxonomic and phylogenetic) allows us to quantify our knowledge and propose research areas that are key to understanding biodiversity evolution.

-

Whittaker 1972Evolution and measurement of species diversityTaxon, 1972

-

Brooks et al. 2006Global biodiversity conservation prioritiesScience, 2006

-

Jarzyna & Jetz 2016Detecting the multiple facets of biodiversityTrends in Ecology & Evolution, 2016

-

Mishler 2023Spatial phylogeneticsJournal of Biogeography, 2023

-

González-Orozco et al. 2011Spatial distribution of species richness and endemism of the genus Acacia in AustraliaAustralian Journal of Botany, 2011

-

Crisp et al. 2001Endemism in the Australian floraJournal of Biogeography, 2001

-

Faith 1992Conservation evaluation and phylogenetic diversityBiological Conservation, 1992

-

Rosauer et al. 2009Phylogenetic endemism: a new approach to identifying geographical concentrations of evolutionary historyMolecular Ecology, 2009

Mexico is among the countries with the utmost vascular plant taxonomic richness in America, only surpassed by Brazil and Colombia (Ulloa-Ulloa et al. 2017). The taxonomic information currently available allows us to highlight that there are around 287 families in the country, of which Asteraceae is one of the 37 families with the highest relative importance to prioritize botanical studies and thus better understand the Flora of Mexico (Murguía-Romero et al. 2023). Currently, the Asteraceae family is classified into 50 tribes (Susanna et al. 2020), of which 26 are found in the country, including 428 genera and approximately 3,127 species (Villaseñor 2018, Redonda-Martínez 2022).

-

Ulloa-Ulloa et al. 2017An integrated assessment of the vascular plant species of the AmericasScience, 2017

-

Murguía-Romero et al. 2023The Kew’s" World Checklist of Vascular Plants" and its relevance to the knowledge of the flora of MexicoBotanical Sciences, 2023

-

Susanna et al. 2020The classification of the Compositae: A tribute to Vicki Ann Funk (1947-2019)Taxon, 2020

-

Villaseñor 2018Diversidad y distribución de la familia Asteraceae en MéxicoBotanical Sciences, 2018

-

Redonda-Martínez 2022Tribus de Asteraceae en México, morfología y clave de identificaciónActa Botanica Mexicana, 2022

Advances in the taxonomy of Asteraceae in Mexico have allowed for improved taxonomic curation of collections and databases, which now constitute key support for describing patterns in their distribution. An evaluation of their richness at broad scales (for example, 1° latitude and longitude grid cells) could serve to contrast results and reduce the spatial bias that still exists in geographic databases (Villaseñor 2018). On the other hand, although the kinship relationships at the species level are far from complete, at the generic level, the phylogenetic knowledge is satisfactory (Qian & Jin 2021, Qian et al. 2024). Tribes Astereae, Cichorieae, Eupatorieae, Heliantheae, and Millerieae include most of the genera in the family, with Astereae and Heliantheae having the most significant number of genera, 53 and 75, respectively (Redonda-Martínez 2022). The meta-phylogeny of Smith & Brown (2018) includes approximately 70 % of the genera of the family in Mexico; similarly, the NCBI nucleotide databases (2024) contain around 80 % of them. Both sets of molecular data would allow obtaining a phylogeny that would help to understand spatial distribution patterns at the genus level from a phylogenetic perspective.

-

Villaseñor 2018Diversidad y distribución de la familia Asteraceae en MéxicoBotanical Sciences, 2018

-

Qian & Jin 2021Are phylogenies resolved at the genus level appropriate for studies on phylogenetic structure of species assemblages?Plant Diversity, 2021

-

Qian et al. 2024Effects of climate and environmental heterogeneity on the phylogenetic structure of regional angiosperm floras worldwideNature Communications, 2024

-

Redonda-Martínez 2022Tribus de Asteraceae en México, morfología y clave de identificaciónActa Botanica Mexicana, 2022

-

Smith & Brown (2018)Constructing a broadly inclusive seed plant phylogenyAmerican Journal of Botany, 2018

-

NCBI, 2024

The genus is a taxonomic category that includes a set of species that share common characteristics among its members and isolate it from another species group (Stuessy 1990, Villaseñor 2004). Its importance, although little explored in biodiversity studies, lies in the fact that the higher the generic alpha diversity in a region, the greater its diversity at other taxonomic levels (e.g., families or species) and the greater its ecological complexity (Villaseñor 2004, Villaseñor et al. 2005, Suárez-Mota et al. 2017). In this way, the genera function as key members for understanding local or regional biodiversity, especially in groups of plants with high taxonomic diversity, as in the Asteraceae family in Mexico.

-

Stuessy 1990Plant Taxonomy, 1990

-

Villaseñor 2004Los géneros de plantas vasculares de la flora de MéxicoBoletín de la Sociedad Botánica de México, 2004

-

Villaseñor 2004Los géneros de plantas vasculares de la flora de MéxicoBoletín de la Sociedad Botánica de México, 2004

-

Villaseñor et al. 2005Higher taxa as surrogates of plant biodiversity in a megadiverse countryConservation Biology, 2005

-

Suárez-Mota et al. 2017Dominios climáticos de la Sierra Madre Oriental y su relación con la diversidad florísticaRevista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 2017

Based on molecular data, the tribe Heliantheae forms a monophyletic group placed within another more inclusive monophyletic group, known as the Heliantheae alliance, along with 11 other tribes (Baldwin et al. 2002, Mandel et al. 2019, Rivera et al. 2021, Susanna et al. 2020, Zhang et al. 2021, 2024). The tribes Coreopsideae and Neurolaeneae appear to be the closest phylogenetically to Heliantheae (Susanna et al. 2020, Zhang et al. 2021, 2024). The tribe is distinguishable by a combination of morphological characters, such as opposite leaves, heterogamous heads with paleae on the receptacle, fertile or sterile female ray florets, hermaphrodite and fertile disk florets, and cypselae with or without pappus of awns, scales, or awns and scales. Its members generally have a base chromosome of x = 19 (Robinson 1981, Baldwin et al. 2002). The phylogeny of the tribe is considered resolved at the subtribe and generic levels (Panero & Jansen 1997, Panero et al. 1999, Plovanich & Panero 2004, Schilling & Panero 2002, 2010, 2011, Moraes & Panero 2016, Tomasello et al. 2019, Freire et al. 2023, Moreira et al. 2023, de Almeida et al. 2024). To date, no studies provide data on its distribution in Mexico using a current circumscription with the phylogenetic approach proposed by Susanna et al. (2020). Therefore, this work aims to evaluate, from a geographical perspective, the alpha diversity of the Heliantheae genera that would allow the recognition of sites with high taxonomic and phylogenetic richness, which could support future criteria to explain their biogeographic history and propose priority sites for their conservation.

-

Baldwin et al. 2002Nuclear rDNA evidence for significant lineages of helenioid Heliantheae (Compositae)Systematic Botany, 2002

-

Mandel et al. 2019A fully resolved backbone phylogeny reveals numerous dispersals and explosive diversifications throughout the history of AsteraceaeProceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2019

-

Rivera et al. 2021The importance of the Mexican taxa of Asteraceae in the family phylogenyJournal of Systematics and Evolution, 2021

-

Susanna et al. 2020The classification of the Compositae: A tribute to Vicki Ann Funk (1947-2019)Taxon, 2020

-

Zhang et al. 2021Phylotranscriptomic insights into Asteraceae diversity, polyploidy, and morphological innovationJournal of Integrative Plant Biology, 2021

-

2024Nuclear phylogenomics of Asteraceae with increased sampling provides new insights into convergent morphological and molecular evolutionPlant Communications, 2024

-

Susanna et al. 2020The classification of the Compositae: A tribute to Vicki Ann Funk (1947-2019)Taxon, 2020

-

Zhang et al. 2021Phylotranscriptomic insights into Asteraceae diversity, polyploidy, and morphological innovationJournal of Integrative Plant Biology, 2021

-

2024Nuclear phylogenomics of Asteraceae with increased sampling provides new insights into convergent morphological and molecular evolutionPlant Communications, 2024

-

Robinson 1981A revision of the tribal and subtribal limits of the Heliantheae (Asteraceae)Smithsonian Contributions to Botany, 1981

-

Baldwin et al. 2002Nuclear rDNA evidence for significant lineages of helenioid Heliantheae (Compositae)Systematic Botany, 2002

-

Panero & Jansen 1997Chloroplast DNA restriction site study of Verbesina (Asteraceae: Heliantheae)American Journal of Botany, 1997

-

Panero et al. 1999Phylogenetic relationships of subtribe Ecliptinae (Asteraceae: Heliantheae) based on chloroplast DNA restriction site dataAmerican Journal of Botany, 1999

-

Plovanich & Panero 2004A phylogeny of the ITS and ETS for Montanoa (Asteraceae: Heliantheae)Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 2004

-

Schilling & Panero 2002A revised classification of subtribe Helianthinae (Asteraceae: Heliantheae). I. Basal lineagesBotanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 2002

-

2010Transfers to Simsia and description of Davilanthus, a new genus of Asteraceae (Heliantheae)Brittonia, 2010

-

2011A revised classification of subtribe Helianthinae (Asteraceae: Heliantheae) II. Derived lineagesBotanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 2011

-

Moraes & Panero 2016A phylogeny of Dimerostemma (Asteraceae, Heliantheae, Ecliptinae) based on the ITS and ETSPhytotaxa, 2016

-

Tomasello et al. 2019Ragweeds and relatives: Molecular phylogenetics of Ambrosiinae (Asteraceae)Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 2019

-

Freire et al. 2023Unraveling polyphyly in Flourensia (Asteraceae, Heliantheae, Enceliinae) and the establishment of a New Genus AustroflourensiaAnais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências, 2023

-

Moreira et al. 2023A time-calibrated phylogeny of Verbesina (Heliantheae-Asteraceae) based on nuclear ribosomal ITS and ETS sequencesEdinburgh Journal of Botany, 2023

-

de Almeida et al. 2024Molecular phylogenetics and historical biogeography of subtribe Ecliptinae (Asteraceae, Heliantheae)Plants, 2024

-

Susanna et al. (2020)The classification of the Compositae: A tribute to Vicki Ann Funk (1947-2019)Taxon, 2020

Materials and methods

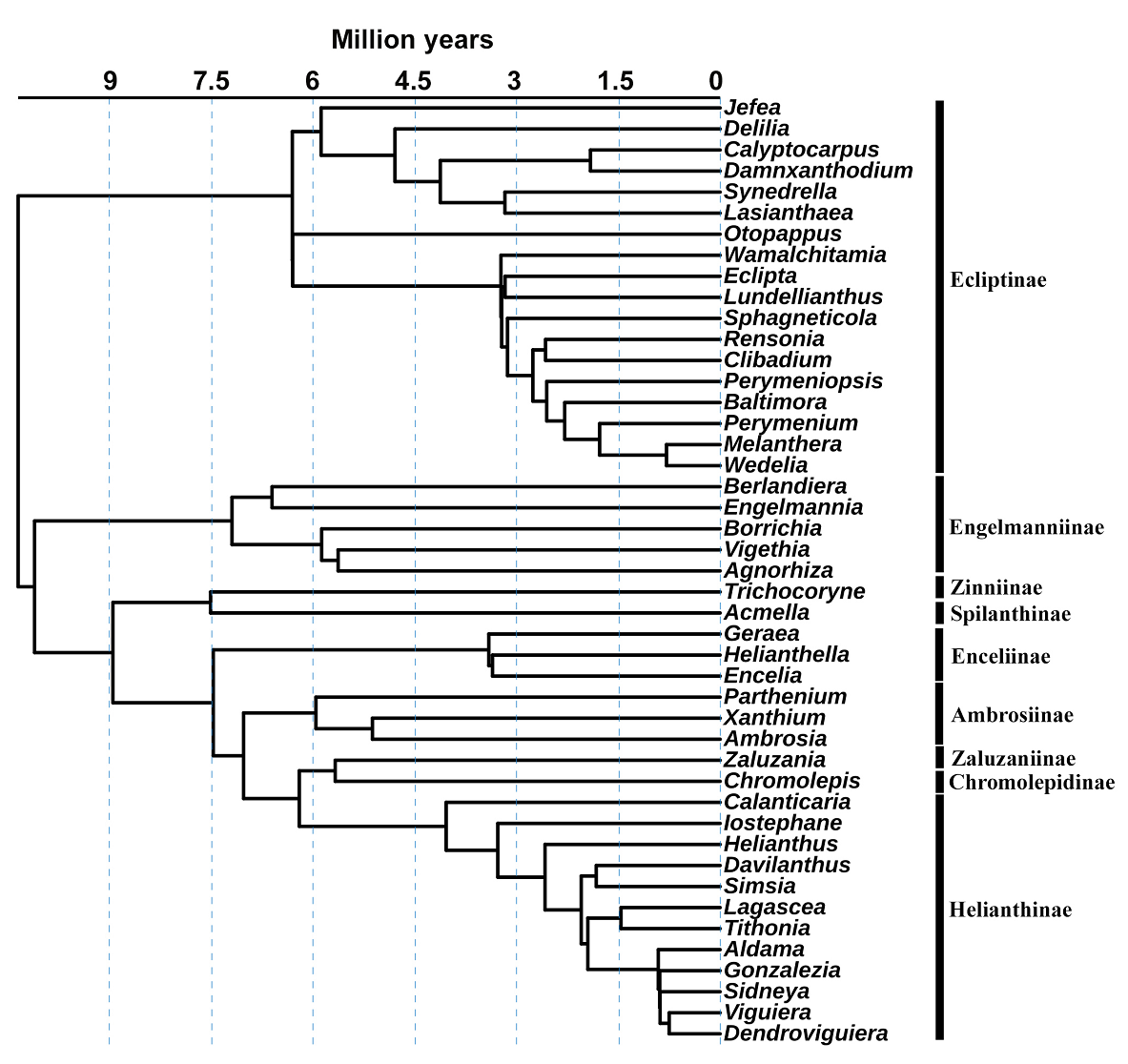

Phylogeny. The function “phylo.maker” of the “U.PhyloMaker” package (Jin & Qian 2023) was used to generate a genera time-calibrated phylogenetic tree derived from the plant mega-phylogeny from Zanne et al. (2014) and Smith & Brown (2018). The phylogenetic tree contains the molecular information for 45 of the 75 genera of Heliantheae present in Mexico (Villaseñor 2018, Redonda-Martínez 2022); no other Heliantheae genera were added to the phylogeny (Figure 1, Table 1).

-

Jin & Qian 2023U. PhyloMaker: An R package that can generate large phylogenetic trees for plants and animalsPlant Diversity, 2023

-

Zanne et al. (2014)Three keys to the radiation of angiosperms into freezing environmentsNature, 2014

-

Smith & Brown (2018)Constructing a broadly inclusive seed plant phylogenyAmerican Journal of Botany, 2018

-

Villaseñor 2018Diversidad y distribución de la familia Asteraceae en MéxicoBotanical Sciences, 2018

-

Redonda-Martínez 2022Tribus de Asteraceae en México, morfología y clave de identificaciónActa Botanica Mexicana, 2022

Thumbnail

Figure 1

Phylogeny of the genera of the tribe Heliantheae (Asteraceae) obtained from the information included in U.PhyloMaker (Jin & Qian 2023).

Phylogeny of the genera of the tribe Heliantheae (Asteraceae) obtained from the information included in U.PhyloMaker (Jin & Qian 2023).

Table 1

Genera of the tribe Heliantheae with distribution in Mexico. Those found in the phylogeny obtained by U.PhyloMaker are marked with an asterisk.

Genera of the tribe Heliantheae with distribution in Mexico. Those found in the phylogeny obtained by U.PhyloMaker are marked with an asterisk.

| Number | Subtribe | Genus |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Spilanthinae | Acmella Rich. ex Pers. * |

| 2 | Engelmanniinae | Agnorhiza (Jeps.) W.A. Weber* |

| 3 | Helianthinae | Aldama La Llave* |

| 4 | Ambrosiinae | Ambrosia L.* |

| 5 | Helianthinae | Bahiopsis Kellogg |

| 6 | Ecliptinae | Baltimora L.* |

| 7 | Engelmanniinae | Berlandiera DC.* |

| 8 | Engelmanniinae | Borrichia Adans.* |

| 9 | Helianthinae | Calanticaria (B.L.Rob. & Greenm.) E.E. Schill. & Panero* |

| 10 | Ecliptinae | Calyptocarpus Less.* |

| 11 | Ecliptinae | Clibadium F.Allam. ex L.* |

| 12 | Chromolepidinae | Chromolepis Benth.* |

| 13 | Ecliptinae | Damnxanthodium Strother* |

| 14 | Helianthinae | Davilanthus E.E. Schill. & Panero * |

| 15 | Ecliptinae | Delilia Spreng* |

| 16 | Helianthinae | Dendroviguiera E.E. Schill. & Panero* |

| 17 | Ambrosiinae | Dicoria Torr. & A. Gray |

| 18 | Ambrosiinae | Dugesia A. Gray |

| 19 | Ecliptinae | Eclipta L.* |

| 20 | Enceliinae | Encelia Adans.* |

| 21 | Engelmanniinae | Engelmannia Torr. & A. Gray* |

| 22 | Ambrosiinae | Euphrosyne DC. |

| 23 | Enceliinae | Flourensia DC. |

| 24 | Enceliinae | Geraea Torr. & A. Gray* |

| 25 | Helianthinae | Gonzalezia E.E. Schill. & Panero* |

| 26 | Ambrosiinae | Hedosyne Strother |

| 27 | Enceliinae | Helianthella Torr. & A. Gray* |

| 28 | Helianthinae | Helianthus L.* |

| 29 | Helianthinae | Heliomeris Nutt. |

| 30 | Zinniinae | Heliopsis Pers. |

| 31 | Zaluzaniinae | Hybridella Cass. |

| 32 | Helianthinae | Hymenostephium Benth. |

| 33 | Helianthinae | Iostephane Benth.* |

| 34 | Ambrosiinae | Iva L. |

| 35 | Ecliptinae | Jefea Strother* |

| 36 | Helianthinae | Lagascea Cav.* |

| 37 | Ecliptinae | Lasianthaea DC.* |

| 38 | Ambrosiinae | Leuciva Rydb. |

| 39 | Ecliptinae | Lundellianthus H. Rob.* |

| 40 | Ecliptinae | Melanthera Rohr* |

| 41 | Montanoinae | Montanoa Cerv. |

| 42 | Ecliptinae | Otopappus Benth.* |

| 43 | Ambrosiinae | Parthenice A. Gray |

| 44 | Ambrosiinae | Parthenium L.* |

| 45 | Ecliptinae | Perymeniopsis H. Rob.* |

| 46 | Ecliptinae | Perymenium Schrad.* |

| 47 | Zinniinae | Philactis Schrad. |

| 48 | Ecliptinae | Plagiolophus Greenm. |

| 49 | Verbesininae | Podachaenium Benth. |

| 50 | Rudbeckiinae | Ratibida Raf. |

| 51 | Ecliptinae | Rensonia S.F. Bake* |

| 52 | Rojasianthinae | Rojasianthe Standl. & Steyerm. |

| 53 | Spilanthinae | Salmea DC. |

| 54 | Zinniinae | Sanvitalia Lam. |

| 55 | Helianthinae | Sclerocarpus Jacq. |

| 56 | Helianthinae | Sidneya E.E. Schill. & Panero* |

| 57 | Helianthinae | Simsia Pers.* |

| 58 | Ecliptinae | Sphagneticola O. Hoffm.* |

| 59 | Spilanthinae | Spilanthes Jacq. |

| 60 | Verbesininae | Squamopappus R.K. Jansen, N.A. Harriman & Urbatsch |

| 61 | Helianthinae | Synedrella Gaertn.* |

| 62 | Zinniinae | Tehuana Panero & Villaseñor |

| 63 | Verbesininae | Tetrachyron Schltdl. |

| 64 | Helianthinae | Tithonia Desf. ex Juss.* |

| 65 | Zinniinae | Trichocoryne S.F. Blake* |

| 66 | Ecliptinae | Tuxtla Villaseñor & Strother |

| 67 | Verbesininae | Verbesina L. |

| 68 | Engelmanniinae | Vigethia W.A. Weber* |

| 69 | Helianthinae | Viguiera Kunth* |

| 70 | Ecliptinae | Wamalchitamia Strother* |

| 71 | Ecliptinae | Wedelia Jacq.* |

| 72 | Ambrosiinae | Xanthium L.* |

| 73 | Zaluzaniinae | Zaluzania Pers.* |

| 74 | Ecliptinae | Zexmenia La Llave |

| 75 | Zinniinae | Zinnia L. |

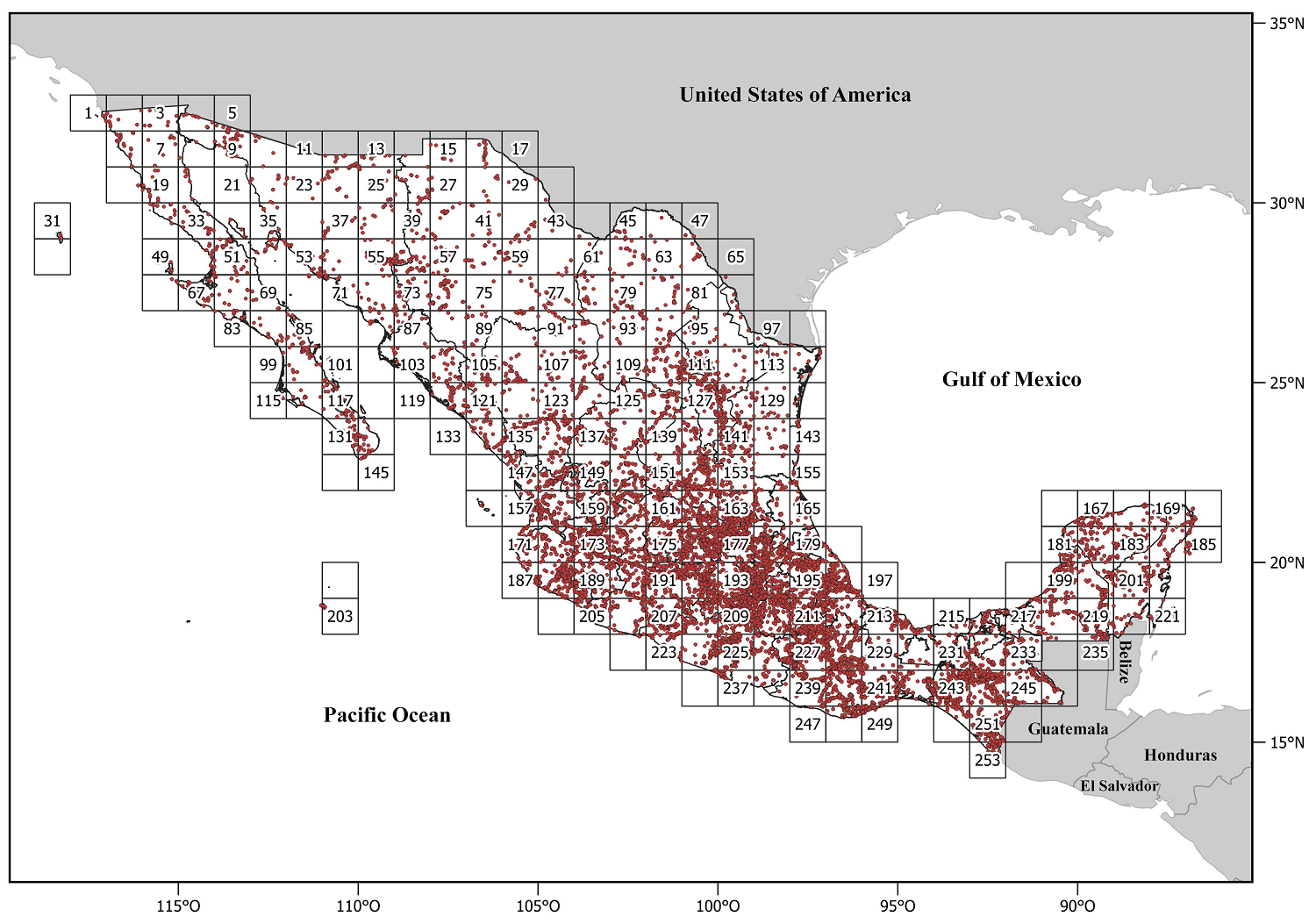

Geographic data. A geo-referenced database was used that includes the 75 genera of Heliantheae distributed in Mexico; such database was built from information contained in the repository of the Sistema Nacional de Información sobre Biodiversidad (SNIB 2024) of the Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO) and the Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México UNAM-IBdata (Murguía-Romero et al. 2024), in addition to a specialized database for the family structured by J. L. Villaseñor (unpublished data). All records of the 75 genera were used to obtain taxonomic alpha diversity values. In contrast, only the distribution data of the 45 genera obtained by the phylogeny were used for the phylogenetic alpha diversity indices. The database includes 22,166 unique records (not counting duplicates) for the 75 genera and 13,251 unique records for the 45 genera included in the phylogeny. The reviewed specimens are deposited in the herbaria ANSM, CHAPA, CREG, CICY, CIIDIR, COCA, CODAGEM, CTES, ECOSUR, ENCB, F, FCME, GH, GUADA, HUAA, HUAZ, HUMO, IBUG, IEB, INEGI, K, LL, MEXU, MICH, MOBG, NY, OAX, QMEX, SERBO, TEX, UADY, UAS, UAGC, UAMIZ, UAT, UCAM, US, SLPM, VT, WIS, XAL, and ZEA (acronyms according to Thiers 2024), as well as the particular collection of the Hinton´s family (GBH, Hinton et al. 2019). To evaluate the genera's taxonomic and phylogenetic alpha diversity, 1° latitude and longitude grid cells were used in which Mexico was divided, considering a total of 253 grid cells (Operational Geographic Units or OGUs, Figure 2).

-

SNIB 2024Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, 2024

-

Murguía-Romero et al. 2024The IBdata Web system for biological collections: Design focused on usabilityBiodiversity Informatics, 2024

-

Thiers 2024Index Herbariorum, 2024

-

Hinton et al. 2019The Hintons’ legacy to the knowledge of the flora of MexicoBotanical Sciences, 2019

Thumbnail

Figure 2

Collecting sites for specimens of Heliantheae (Asteraceae) genera in Mexico. The country was divided into 253 grid cells of 1° latitude and longitude.

Collecting sites for specimens of Heliantheae (Asteraceae) genera in Mexico. The country was divided into 253 grid cells of 1° latitude and longitude.

Alpha diversity. For each of the 253 OGUs, we calculated the genera richness (TR), phylogenetic diversity (PD), weighted endemism (WE), and phylogenetic endemism (PE) using the Biodiverse program (Laffan et al. 2010). We performed a Spearman correlation test using the different taxonomic and phylogenetic diversity values employing R Core Team (2024) to evaluate the correlation between the other variables. Finally, we mapped the results using the QGIS v. 3.14 (2020) package.

-

Laffan et al. 2010Biodiverse, a tool for the spatial analysis of biological and related diversityEcography, 2010

-

R Core Team (2024)R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, 2024

-

QGIS v. 3.14 (2020)QGIS, 2020

Results

Phylogeny (Figure 1). The phylogeny does not contain genera from the subtribes Ambrosiinae (seven), Ecliptinae (three), Enceliinae (two), Helianthinae (three), Montanoinae (one), Rojasianthinae (one), Rudbeckiinae (one), Spilanthinae (two), Verbesininae (four), Zaluzaniinae (one), and Zinniinae (five). These genera not included in phylogeny show different distribution ranges, from broader to restricted to two cells.

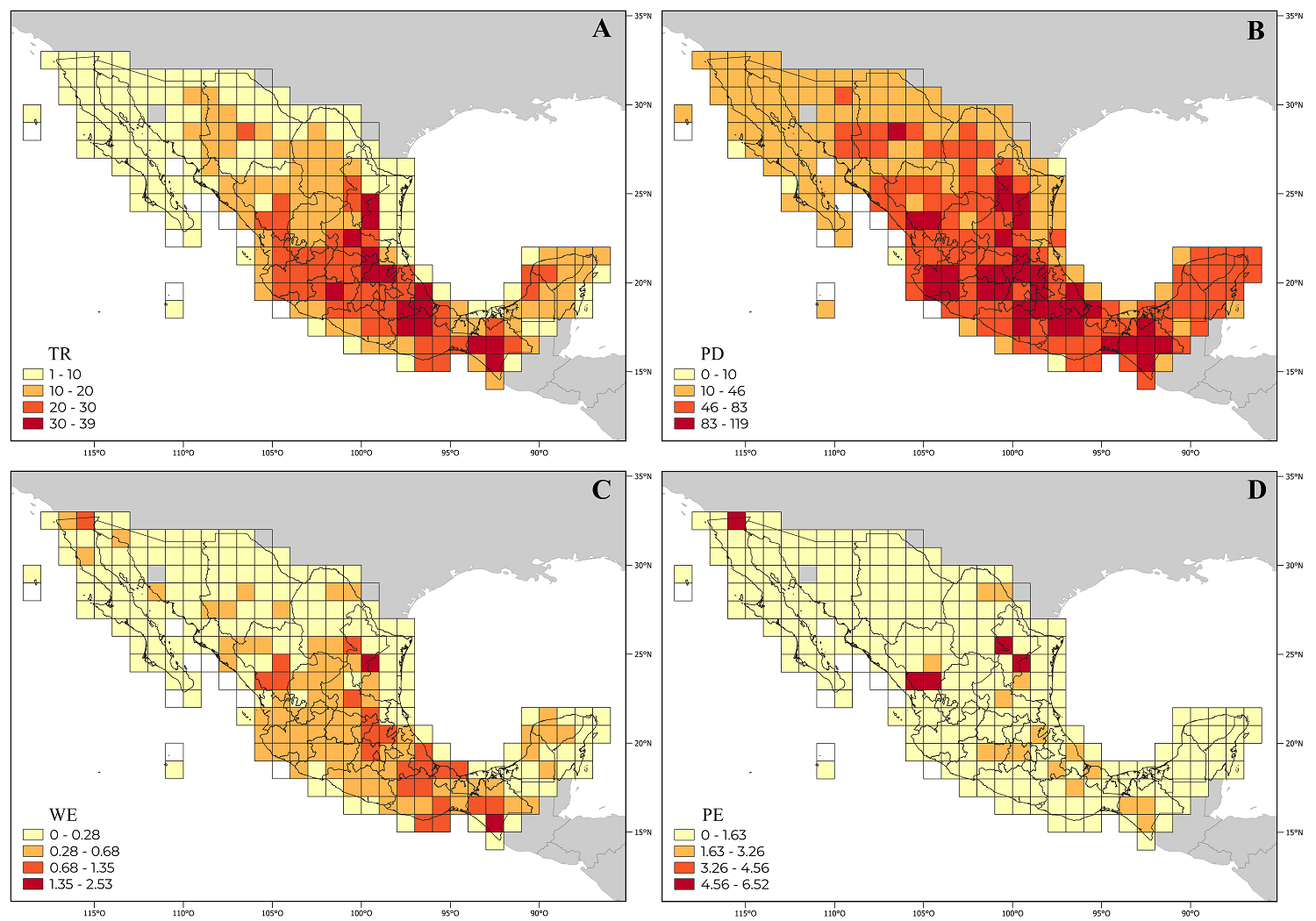

Taxonomic and phylogenetic alpha diversity. The Heliantheae genus richness (TR) varies between 1 and 39 per OGU (Supplementary data). The cells with the highest richness are in the states of Chiapas, Hidalgo, Michoacán, Nuevo León, Oaxaca, Puebla, Querétaro, San Luis Potosí, and Veracruz (Figure 3A). This pattern is like that found for phylogenetic diversity (PD) (Figure 3B); in fact, both values show a significant positive correlation (rho = 0.96, P < 0.001, Table 2), greater than between TR and the other values (Table 2).

Thumbnail

Figure 3

Distribution of genera of the Heliantheae tribe in Mexico. Cells in yellow show lower alpha diversity than those with red colors. A. Genus richness (TR). B. Phylogenetic diversity (PD). C. Weighted endemism (WE). D. Phylogenetic endemism (PE).

Distribution of genera of the Heliantheae tribe in Mexico. Cells in yellow show lower alpha diversity than those with red colors. A. Genus richness (TR). B. Phylogenetic diversity (PD). C. Weighted endemism (WE). D. Phylogenetic endemism (PE).

Table 2

Spearman correlation (rho) values found when alpha diversity variables for the Mexican genera of Heliantheae are analyzed. The correlation was determined using the grid cells into which the country was divided (Figure 2). PD: Phylogenetic diversity, PE: Phylogenetic endemism, TR: Genera richness, WE: Weighted endemism. Confidence interval: 95%, p < 0.001.

Spearman correlation (rho) values found when alpha diversity variables for the Mexican genera of Heliantheae are analyzed. The correlation was determined using the grid cells into which the country was divided (Figure 2). PD: Phylogenetic diversity, PE: Phylogenetic endemism, TR: Genera richness, WE: Weighted endemism. Confidence interval: 95%, p < 0.001.

| Variable | TR | PD | WE | PE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TR | 1 | |||

| PD | 0.96 | 1 | ||

| WE | 0.91 | 0.87 | 1 | |

| PE | 0.87 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 1 |

Grid cells with a high weighted endemism (WE) value were identified in the states of Baja California, Chiapas, Durango, Hidalgo, Nuevo León, Oaxaca, Puebla, Querétaro, San Luis Potosí, and Veracruz (Figure 3C). The grid cell 251 in Chiapas stands out with significant WE value, characterized by the presence of genera with almost exclusive distribution, such as Rensonia S.F. Blake, whose distribution extends to Guatemala, El Salvador, and Costa Rica, as well as Rojasianthe Standl. & Steyerm. and Squamopappus R.K. Jansen, N.A. Harriman & Urbatsch also recorded in Guatemala.

Four grid cells (3, 111, 128, 136) with important phylogenetic endemism values (PE) stand out (Figure 3D, Table 3). Grid 3 is in the extreme north of Baja California, characterized by Agnorhiza (Jeps.) W.A. Weber, a genus with a distribution extending to California, USA. The grid cell 136 is in Durango, where Chromolepis Benth., Damnxanthodium Strother, and Trichocoryne S.F. Blake are distributed, all endemic to Mexico. Finally, grids 111 and 128 are in Nuevo León, characterized by the distribution of Engelmannia Torr. & A. Gray, a genus with a broader distribution toward the central plains of the United States, and Vigethia W.A. Weber, a genus endemic to Mexico. All the genera mentioned constitute elements positioned principally in subtribes with long branches of the phylogeny (Figure 1).

Table 3

Cells with the highest alpha diversity values for the genera of Heliantheae in Mexico. PD: phylogenetic diversity. PE: Phylogenetic endemism. TR: Genera richness. WE: Weighted endemism.

Cells with the highest alpha diversity values for the genera of Heliantheae in Mexico. PD: phylogenetic diversity. PE: Phylogenetic endemism. TR: Genera richness. WE: Weighted endemism.

| Grid cell | TR (TR/Total |

WE (WE/Total number |

PD (PD/Total length of |

PE (PE/Total length of |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 228 | 39 (52 %) | 1.219 (5 %) | 108.714 (56 %) | 1.796 (< 1 %) |

| 211 | 39 (52 %) | 1.016 (3 %) | 102.324 (52 %) | 1.65 (< 1 %) |

| 178 | 35 (47 %) | 0.898 (3 %) | 99.395 (51 %) | 1.741 (< 1 %) |

| 196 | 38 (51 %) | 0.963 (3 %) | 116.028 (59 %) | 2.049 (1 %) |

| 128 | 31 (41 %) | 1.351 (4 %) | 118.681 (61 %) | 6.521 (3 %) |

| 251 | 31 (41 %) | 2.528 (8 %) | 87.523 (45 %) | 2.631 (1 %) |

| 212 | 32 (42 %) | 0.734 (2 %) | 100.062 (51 %) | 1.56 (< 1 %) |

| 141 | 31 (41 %) | 0.634 (2 %) | 100.423 (51 %) | 1.68 (< 1 %) |

| 191 | 31 (41 %) | 0.609 (1 %) | 94.218 (48 %) | 1.895 (< 1 %) |

| 136 | 26 (35 %) | 1.322 (4 %) | 99.152 (51 %) | 6.294 (3 %) |

| 178 | 35 (47 %) | 0.898 (2 %) | 99.395 (50 %) | 1.741 (< 1 %) |

| 177 | 35 (47 %) | 0.824 (2 %) | 94.809 (48 %) | 1.423 (< 1 %) |

| 244 | 33 (44 %) | 1.271 (3 %) | 88.72 (45 %) | 1.66 (< 1 %) |

| 111 | 26 (34 %) | 1.215 (4 %) | 98.922 (50 %) | 5.978 (3 %) |

| 152 | 32 (42 %) | 0.734 (2 %) | 109.183 (55 %) | 1.779 (< 1 %) |

| 227 | 33 (43 %) | 0.739 (2 %) | 97.786 (50 %) | 1.57 (< 1 %) |

| 192 | 28 (37 %) | 0.613 (2 %) | 94.741 (48 %) | 1.949 (< 1 %) |

| 3 | 5 (6 %) | 1.168 (23 %) | 41.666 (21 %) | 6.517 (3 %) |

| 163 | 35 (47 %) | 0.726 (2 %) | 100.653 (51 %) | 1.443 (< 1 %) |

| 225 | 30 (40 %) | 0.442 (1 %) | 92.184 (47 %) | 1.136 (< 1 %) |

Table 3 includes the 20 cells that showed the highest values for the variables considered. In addition, the table contains the richness ratio for the taxonomic indices, which reflects the relationship between taxonomic values and total richness at a site. For phylogenetic data, the table includes the relationship between phylogenetic values and the lengths of each branch of the pruned tree. These proportions allow identifying sites that, despite having low taxonomic or phylogenetic diversity, have high-weighted endemism or phylogenetic endemism, as in grid cell 3 (Table 3).

Discussion

The alpha diversity analysis of the Heliantheae genera in Mexico allowed the detection of essential centers of taxonomic richness and endemism (TR and WE), and phylogenetic diversity and endemism (PD and PE). These identified grid cells, under different approaches focusing on biodiversity, could help formulate alternatives to explain the evolutionary histories of their components and propose priority sites for conservation (Jarzyna & Jetz 2016). The examples mentioned in the following paragraphs, highlight the taxonomic or phylogenetic diversity relevance of some parts of the Mexican territory, potentially serving as elements for the authorities in charge of biodiversity conservation to consider different viewpoints to assess diversity, as discussed in other countries by authors such as Daru et al. (2019), Nitta et al. (2022) or Lu et al. (2023).

-

Jarzyna & Jetz 2016Detecting the multiple facets of biodiversityTrends in Ecology & Evolution, 2016

-

Daru et al. (2019)Spatial overlaps between the global protected areas network and terrestrial hotspots of evolutionary diversityGlobal Ecology and Biogeography, 2019

-

Nitta et al. (2022)Spatial phylogenetics of Japanese ferns: Patterns, processes, and implications for conservationAmerican Journal of Botany, 2022

-

Lu et al. (2023)A comprehensive evaluation of flowering plant diversity and conservation priority for national park planning in ChinaFundamental Research, 2023

The higher alpha diversity, taxonomic and phylogenetic, occurs in many grid cells throughout the country, especially in its eastern part, from Nuevo León to Chiapas (Figure 3). Considering the taxonomic richness, its levels of endemicity have already been discussed and evaluated both by the entire richness of genera in the family (Villaseñor 1990) and for the tribe Heliantheae in particular (Villaseñor 1991). The distribution patterns observed for the tribe partially coincide with the taxonomic distribution of the flora at the species level (Villaseñor & Meave 2022). Likewise, from the phylogenetic and biogeographic viewpoints, significant similarities are observed; the results obtained here do not differ from those obtained for the species of the North American flora (Mishler et al. 2020) or Mexico (Sosa et al. 2018).

-

Villaseñor 1990Fitogeografía del valle de Tehuacán-CuicatlánBotanical Sciences, 1990

-

Villaseñor 1991Las Heliantheae endémicas a México: una guía hacia la conservaciónActa Botanica Mexicana, 1991

-

Villaseñor & Meave 2022Floristics in Mexico today: insights into a better understanding of biodiversity in a megadiverse countryBotanical Sciences, 2022

-

Mishler et al. 2020Spatial phylogenetics of the North American floraJournal of Systematics and Evolution, 2020

-

Sosa et al. 2018Evolutionary history of the flora of Mexico: Dry forests cradles and museums of endemismJournal of Systematics and Evolution, 2018

Heliantheae taxonomic and phylogenetic alpha diversity concentrates in both the Neotropical region and the Mexican Transition Zone (Morrone 2019, Villaseñor et al. 2020), characterizing regions mainly associated with the country's mountain ranges (CONABIO 1997). The Trans Mexican Volcanic Belt (Eje Volcánico) and the Balsas Depression (grid cells 191, 192, and 201), the mountains of central Veracruz (grid cell 196), the mountains of northern Oaxaca (portions of grid cells 212 and 228), the Sierra Madre Occidental (grid cells 135 and 136), the Sierra Madre Oriental (grid cells 111, 128, 141, 153, 163, 177, and 178), the east of the Sierra Madre del Sur (grid cells 225 and 227), and the Soconusco region (grid cell 251) stand out. It is also possible to highlight grid cells 3 and 152 located in arid and semi-arid areas, the first in the northern part of the country in a portion of the Californian and Sonoran biogeographic provinces, the other in the Southern Altiplano (Southern Highland, CONABIO 1997).

-

Morrone 2019Regionalización biogeográfica y evolución biótica de México: encrucijada de la biodiversidad del Nuevo MundoRevista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 2019

-

Villaseñor et al. 2020The breadth of the Mexican Transition Zone as defined by its flowering plant generic floraPlos One, 2020

-

CONABIO 1997Provincias biogeográficas de México, escala 1:4000000. México. 1997, 1997

-

CONABIO 1997Provincias biogeográficas de México, escala 1:4000000. México. 1997, 1997

In the Mexican Altiplano (Highland), important cells were identified for their number of Heliantheae genera; for example, in this region, high values of TR and PD are recorded in the center of San Luis Potosí (grid cell 152), where the occurrence of genera that are mainly associated with arid or semi-arid environments stands out, such as Berlandiera DC., Dugesia, or Jefea Strother (Pinkava 1967, Villaseñor 1990, Villaseñor & Téllez-Valdés 2004). Other critical areas with TR and PD values are in the Trans Mexican Volcanic Belt and the Balsas Depression, particularly in central and western Michoacán and southern Puebla (grid cells 191, 192, and 211), with genera from both temperate forests (Lasianthaea DC., Perymenium Schrad., and Verbesina L.) and seasonally dry tropical forests (Dendroviguiera E.E.Schill. & Panero) (Villaseñor et al. 2021).

-

Pinkava 1967Biosystematic study of Berlandiera (Compositae)Brittonia, 1967

-

Villaseñor 1990Fitogeografía del valle de Tehuacán-CuicatlánBotanical Sciences, 1990

-

Villaseñor & Téllez-Valdés 2004Distribución potencial de las especies del género Jefea (Asteraceae) en MéxicoAnales del Instituto de Biología. Serie Botánica, 2004

-

Villaseñor et al. 2021Transition zones and biogeographic characterization of endemism in three biogeographic provinces of central MexicoBotanical Sciences, 2021

Due to their genus richness, other significant regions are in northern Oaxaca, southern Puebla, and western Veracruz (grid cells 212 and 228). For Puebla in particular, this region stands out as necessary for conservation considering their endemic species (Villaseñor et al. 2023b); a representative of the tribe in this region is the genus Davilanthus (Schilling & Panero 2010). These grid cells constitute part of a region of great biogeographic interest due to its high biological diversity, the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Valley floristic province (Rzedowski 1978, Villaseñor et al. 1990, Villaseñor et al. 2023b). Its phylogenetic endemism located in grid cell 211 has a significant number of nearly endemic species of Puebla and species of Cactaceae, categorized as a region of mixed endemism, including both neo- and paleo-endemic species (Villaseñor et al. 2023b, Soto-Trejo et al. 2024).

-

Villaseñor et al. 2023bThe vascular plant species endemic or nearly endemic to Puebla, MexicoBotanical Sciences, 2023

-

Schilling & Panero 2010Transfers to Simsia and description of Davilanthus, a new genus of Asteraceae (Heliantheae)Brittonia, 2010

-

Rzedowski 1978Vegetación de México, 1978

-

Villaseñor et al. 1990The genera of Asteraceae endemic to Mexico and adjacent regionsAliso: A Journal of Systematic and Floristic Botany, 1990

-

Villaseñor et al. 2023bThe vascular plant species endemic or nearly endemic to Puebla, MexicoBotanical Sciences, 2023

-

Villaseñor et al. 2023bThe vascular plant species endemic or nearly endemic to Puebla, MexicoBotanical Sciences, 2023

-

Soto-Trejo et al. 2024The evolution of paleo-and neo-endemic species of Cactaceae in the isolated Valley of Tehuacán-Cuicatlán, MexicoPlant Ecology and Evolution, 2024

Similarly, in southern Mexico, Aragón-Parada et al. (2023) considered the Sierra Madre del Sur province as a significant center of taxonomic and phylogenetic diversity; in this study, grid cells 225 and 227 are identified as worthy for their genera richness. Another region equally remarkable for its endemism is the Soconusco (grid cell 251), in the state of Chiapas, which records high WE and PE values; here is located an important center of endemism for the tribe, previously identified by Villaseñor (1991) considering a broader taxonomic circumscription of the tribe. The Chiapas mountains are characterized by genera of restricted distribution, an area identified as relevant for its biodiversity and endemism, both taxonomic (for example, González-Espinosa et al. 1997, Beutelspacher et al. 2017, Villaseñor et al. 2013) and phylogenetic (Sosa et al. 2018).

-

Aragón-Parada et al. (2023)Spatial phylogenetics of the flora in the Sierra Madre del Sur, Mexico: Evolutionary puzzles in tropical mountainsJournal of Biogeography, 2023

-

Villaseñor (1991)Las Heliantheae endémicas a México: una guía hacia la conservaciónActa Botanica Mexicana, 1991

-

González-Espinosa et al. 1997Contexto vegetacional y florístico de la agriculturaLos Altos de Chiapas: Agricultura y Crisis Rural. Tomo 1. Los Recursos Naturales, 1997

-

Beutelspacher et al. 2017Flora vascular del municipio de San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas, MéxicoLacandonia, 2017

-

Villaseñor et al. 2013La familia Asteraceae en el municipio de San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas, MéxicoLacandonia, 2013

-

Sosa et al. 2018Evolutionary history of the flora of Mexico: Dry forests cradles and museums of endemismJournal of Systematics and Evolution, 2018

In northern Mexico, along the Sierra Madre Occidental in Durango, grid cell 136 stands out for its WE, PD, and PE values. Endemic or almost endemic genera, such as Chromolepis, Damnxanthodium, and Trichocoryne, occur there. Similarly, grid cell 3, located in Mexicali and its surroundings in Baja California, occupies part of the Californian and Sonoran provinces. However, only five genera are recorded there, with high WE and PE values (Table 3), undoubtedly due to the restricted presence of Agnorrhiza, reaching its southern distribution limit here. In northeastern Mexico, along the Sierra Madre Oriental, two diversity centers are identified; one includes grid cells 111, 128, and 141, the two first ones standing out for their high WE and PE values where the distribution of the genera Engelmannia and Vigethia is recorded, genera with an affinity for temperate biomes. These same grid cells have been identified with high endemism richness (667 and 581 species, respectively), with affinities to the temperate and xerophilous scrub biomes (Villaseñor et al. 2023a). Grid cell 141, for its part, recorded important values of TR and PD; this grid cell has the highest taxonomic alpha diversity, both richness, and endemism at the species level for the northeast region of Mexico (Villaseñor et al. 2023a). This places the grid cell as necessary for conservation not only for the tribe but also for the flora in general.

-

Villaseñor et al. 2023aDiversidad florística de la región noreste de México, estados de Coahuila, Nuevo León y TamaulipasBotanical Sciences, 2023

-

Villaseñor et al. 2023aDiversidad florística de la región noreste de México, estados de Coahuila, Nuevo León y TamaulipasBotanical Sciences, 2023

Another center of diversity in this mountain range includes grid cells 163, 177, and 178, located in the southern part of the province known as Carso Huasteco (Villaseñor & Ortiz 2022), where it joins the provinces of Altiplano Sur and Trans Mexican Volcanic Belt; there, significant values of TR and PD stand out, grid cells 163 and 177 concentrating more than 1,000 species (Villaseñor & Ortiz 2022). This part of the country should be considered crucial for its conservation, not only for the Heliantheae tribe but for all other species of vascular plants it includes. The genera Perymeniopsis H. Rob. and Tetrachyron Schltdl. occur in the mountainous parts of these grid cells, in biomes such as temperate and humid mountain forests (Villaseñor 2010).

-

Villaseñor & Ortiz 2022A phytogeographic assessment of the Sierra Madre Oriental physiographic province, MexicoBotanical Sciences, 2022

-

Villaseñor & Ortiz 2022A phytogeographic assessment of the Sierra Madre Oriental physiographic province, MexicoBotanical Sciences, 2022

-

Villaseñor 2010El bosque húmedo de montaña en México y sus plantas vasculares: Catálogo florístico-taxonómico, 2010

The results suggest that the Heliantheae tribe has a chief influence on the biogeographic history of Mexico. Its origins date back 10 million years (Mya), during the geological events of the late Miocene to the late Pliocene, characterized by volcanism in different parts of the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt and culminating 3 Mya (Ferrari et al. 1999, 2012) with aridity events (Graham 2018). They all helped establish most lineages of the subtribes (Figure 1). Likewise, the cycles of glaciation and aridity during the Pleistocene, between 2.58 Mya and the present (Metcalfe et al. 2000), gave rise to other genera of Heliantheae.

-

Ferrari et al. 1999Space-time patterns of Cenozoic arc volcanism in central Mexico: from the Sierra Madre Occidental to the Mexican Volcanic BeltGeology, 1999

-

2012The dynamic history of the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt and the Mexico subduction zoneTectonophysics, 2012

-

Graham 2018The role of land bridges, ancient environments, and migrations in assembling the North American floraJournal of Systematics and Evolution, 2018

-

Metcalfe et al. 2000Records of Late Pleistocene-Holocene climatic change in Mexico -a reviewQuaternary Science Reviews, 2000

Another time-calibrated phylogeny proposes that Heliantheae originated around 30 Mya (Rivera et al. 2021), hypothesizing their origins because of the geological events as the formation of the Sierra Madre Occidental, the Sierra Madre Oriental, and Sierra Madre del Sur and probably more tropical climates (Cevallos-Ferriz et al. 2012). However, we use a time-calibrated phylogeny here according to the Phylomaker tree (Jin & Qian 2023), like Mandel et al. (2019).

-

Rivera et al. 2021The importance of the Mexican taxa of Asteraceae in the family phylogenyJournal of Systematics and Evolution, 2021

-

Cevallos-Ferriz et al. 2012Perspectiva paleobotánica y geológica de la biodiversidad en MéxicoActa Botanica Mexicana, 2012

-

Jin & Qian 2023U. PhyloMaker: An R package that can generate large phylogenetic trees for plants and animalsPlant Diversity, 2023

-

Mandel et al. (2019)A fully resolved backbone phylogeny reveals numerous dispersals and explosive diversifications throughout the history of AsteraceaeProceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2019

Studies on spatial phylogenetics conducted in families such as Cactaceae and Orchidaceae (Amaral et al. 2022, Gutiérrez-Rodríguez et al. 2022) contrast in their PD and PE results concerning Heliantheae. A plausible explanation for these differences is the unlike environments in which these families have diversified. Cactaceae, for example, are distributed primarily in arid and semi-arid areas of the Mexican Plateau, while Orchidaceae is preferentially found in the tropical regions of southern and southeastern Mexico. In contrast, Heliantheae genera positively occur in more temperate climates throughout the mountainous areas, although they also thrive in the country's semi-arid regions. In the same sense, the results shown here partially contrast with those obtained by Sosa et al. (2018), who analyzed lineages for dry forest taxa. In these forests, the proportion of genera of the Heliantheae tribe is lower, although the results shown here locate certain critical areas also identified by Sosa et al. (2018) within this environment. An example is the biogeographic province Depresión del Balsas (Balsas Depression, CONABIO 1997), where grid cells 191, 192, and 208 are located, recording high TR and PD values (Supplementary Material).

-

Amaral et al. 2022Spatial patterns of evolutionary diversity in Cactaceae show low ecological representation within protected areasBiological Conservation, 2022

-

Gutiérrez-Rodríguez et al. 2022Phylogenetic endemism of the orchids of Megamexico reveals complementary areas for conservationPlant Diversity, 2022

-

Sosa et al. (2018)Evolutionary history of the flora of Mexico: Dry forests cradles and museums of endemismJournal of Systematics and Evolution, 2018

-

Sosa et al. (2018)Evolutionary history of the flora of Mexico: Dry forests cradles and museums of endemismJournal of Systematics and Evolution, 2018

-

CONABIO 1997Provincias biogeográficas de México, escala 1:4000000. México. 1997, 1997

We suggest that Heliantheae taxonomic and phylogenetic alpha diversity values reflect biogeographic patterns that will not change drastically when new information is incorporated at the generic level, at least for TR and PD metrics. Their high correlation (> 0.9) suggests that using either alpha biodiversity index would allow the same alpha spatial patterns to be determined. Accordingly, we consider the phylogenetic tree balanced in terms of taxonomic representativeness and geographic distribution of taxa. In this context, a study in Mexico focused on the Sierra Madre del Sur province (Aragón-Parada et al. 2023) used a phylogeny with all the taxa distributed in this province and scenario 3 of the “PhyloMaker” package to add just over 30 % of the missing species. The authors obtained high correlation values between the TR and the PD. Although we did not include the missing Heliantheae genera, the classification between the TR and PD indices is very high, which indicates a good representativeness of the genera of this tribe. However, it is possible that at the species level, using only the taxa with molecular data in PhyloMaker, the relationships will change due to the low representativeness of the phylogeny or the spatial bias in its known distribution (Rodrigues & Gaston 2002).

-

Aragón-Parada et al. 2023Spatial phylogenetics of the flora in the Sierra Madre del Sur, Mexico: Evolutionary puzzles in tropical mountainsJournal of Biogeography, 2023

-

Rodrigues & Gaston 2002Maximising phylogenetic diversity in the selection of networks of conservation areasBiological Conservation, 2002

Although the metrics are correlated, they could not function as surrogates for each other, or at least this is not advisable when biodiversity conservation is the objective. To discuss conservation issues, the phylogenetic diversity index (PD) has been proposed as a better metric to describe biodiversity than the taxonomic index (TR) (Miller et al. 2018). Other alternatives suggest integrating metrics such as taxonomic diversity (TR, WE), phylogenetic diversity (PD, PE), and evolutionary distinctiveness (ED) in a complementary analysis to prioritize areas (Lu et al. 2023). For example, cells with the same TR = 10 can have PD values between 29.9 and 61.6 (Supplementary Material). In conservation analysis, deciding if prioritized cells have high TR or PD or a balance in both perspectives is essential.

-

Miller et al. 2018Phylogenetic diversity is a better measure of biodiversity than taxon countingJournal of Systematics and Evolution, 2018

-

Lu et al. 2023A comprehensive evaluation of flowering plant diversity and conservation priority for national park planning in ChinaFundamental Research, 2023

The lower correlation between WE and PE than the other indices may increase when considering a complete phylogeny. According to the Rosauer et al. (2009) formula, phylogenetic endemism would be more significant if endemic genera were included in long branches. For example, other important centers of endemism are grid cells 213, 214, 241, 248, and 249, which show high WE value (Supplementary Material) but are not detected as relevant for their PE because the genera in these cells are not found in the phylogeny used.

-

Rosauer et al. (2009)Phylogenetic endemism: a new approach to identifying geographical concentrations of evolutionary historyMolecular Ecology, 2009

Including these missing genera could provide valuable information. Their inclusion could be through using the morphological relationships considered by taxonomists and postulating them as a proposal for kinship. Missing genera can be included based on their classification at the subtribe level, such as Dicoria Torr. & A. Gray and Parthenice A. Gray (subtribe Ambrosiinae), restricted to specific grid cells in the northeast of the country (grid cells 53 and 73, respectively). Both genera are part of a long branch due to their classification in the subtribe Ambrosiinae. Similarly, Dugesia A. Gray, a genus restricted to central Mexico (grid cells 177, 178,192, 193, 194, 195, 211, and 212), could be included as a member of a long branch by its classification into the subtribe Ambrosiinae, or Plagiolophus Greenm. and Tuxtla Villaseñor & Strother, the former distributed in Campeche and Yucatán (grid cells 167, 181, 182, 183, and 199), and the latter restricted to southern Veracruz (grid cells 213 and 214). Both correspond to a long-branch clade in the subtribe Ecliptinae. A final example is Tehuana Panero & Villaseñor, endemic to southeastern Oaxaca (grid cells 241, 248, and 249), which would be included as a member of a long branch within the subtribe Zinniineae.

Considering both taxonomic and phylogenetic diversity, several grid cells discussed have also been identified as important centers of diversity when analyzing species of the Asteraceae family (Suárez-Mota et al. 2017), Cactaceae (Amaral et al. 2022), or the entire flora of dry forests (Sosa et al. 2018). The taxonomic and phylogenetic alpha diversity values of Heliantheae, especially WE and PE, could be used as essential elements for conservation at the genus level, regardless of the coarse scale used here. In addition to conserving Heliantheae genera with a particular evolutionary history, they could help in the preservation of their associated flora because of the strong correlation between members of the family and other members of the flora (Villaseñor et al. 2005, Villaseñor et al. 2007).

-

Suárez-Mota et al. 2017Dominios climáticos de la Sierra Madre Oriental y su relación con la diversidad florísticaRevista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 2017

-

Amaral et al. 2022Spatial patterns of evolutionary diversity in Cactaceae show low ecological representation within protected areasBiological Conservation, 2022

-

Sosa et al. 2018Evolutionary history of the flora of Mexico: Dry forests cradles and museums of endemismJournal of Systematics and Evolution, 2018

-

Villaseñor et al. 2005Higher taxa as surrogates of plant biodiversity in a megadiverse countryConservation Biology, 2005

-

Villaseñor et al. 2007Plant families as predictors of plant biodiversity in MexicoDiversity and Distributions, 2007

We propose analyzing all these indices separately, based on the existing set of indexes, to assess phylogenetic alpha diversity. Our approach complements the regions identified formerly through alpha taxonomic diversity. It may provide a more comprehensive understanding when applied to different taxonomic categories (e.g., species) or alternative methodologies (CANAPE, Mishler et al. 2014).

-

Mishler et al. 2014Phylogenetic measures of biodiversity and neo-and paleo-endemism in Australian AcaciaNature Communications, 2014

No Mexican Heliantheae genera or species are considered in CITES Appendices (CITES 2025) or NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010 (SEMARNAT 2010). Only 373 species of Asteraceae (94 of them members of Heliantheae) are considered rare, only recorded in a single 1° longitude and latitude grid cell (Villaseñor et al. 2024); most of them should be considered in Red List categories (IUCN 2023).

-

CITES 2025Appendices, 2025

-

SEMARNAT 2010Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010, Protección ambiental - Especies nativas de México de flora y fauna silvestres - Categorías de riesgo y especificaciones para su inclusión, exclusión o cambio - Lista de especies en riesgoDiario Oficial de la Federación, 2019

-

Villaseñor et al. 2024The rarest of rarities in the flora of MexicoBotanical Sciences, 2024

-

IUCN 2023The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, 2023

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here: https://doi.org/10.17129/botsci.3661

Supplemental data

Acknowledgments

This paper is part of the first author’s dissertation. It is presented as a partial requirement to meet the requirements to obtain the Ph.D. degree at the Programa de Doctorado en Ciencias Biologicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). Comments on the manuscript by Liliana López-Olmedo, Lourdes Sandoval-García, Miguel Murguía-Romero, and Enrique Ortiz are greatly appreciated. The editor and reviewers are sincerely thanked for their time and effort in reviewing and commenting on this manuscript.

Literature cited

- Amaral DT, Bonatelli IA, Romeiro-Brito M, Moraes EM, Franco FF. 2022. Spatial patterns of evolutionary diversity in Cactaceae show low ecological representation within protected areas. Biological Conservation 273: 109677. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2022.109677 Links

- Aragón-Parada J, Carrillo-Reyes P, Rodríguez A, Munguía-Lino G, Salinas-Rodríguez MM, De-Nova JA. 2023. Spatial phylogenetics of the flora in the Sierra Madre del Sur, Mexico: Evolutionary puzzles in tropical mountains. Journal of Biogeography 50: 1679-1691. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.14679 Links

- Baldwin BG, Wessa BL, Panero JL. 2002. Nuclear rDNA evidence for significant lineages of helenioid Heliantheae (Compositae). Systematic Botany 27: 161-198. Links

- Beutelspacher CR, Villaseñor JL, Gómez-López A, García-Martínez R, Martínez-Icó M. 2017. Flora vascular del municipio de San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas, México. Lacandonia 11: 21-139. Links

- Brooks TM, Mittermeier RA, Da Fonseca GA, Gerlach J, Hoffmann M, Lamoreux JF, Mittermeier CG, Pilgrim JD, Rodrigues AS. 2006. Global biodiversity conservation priorities. Science 313: 58-61. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1127609 Links

- Cevallos-Ferriz SR, González-Torres EA, Calvillo-Canadell L. 2012. Perspectiva paleobotánica y geológica de la biodiversidad en México. Acta Botanica Mexicana 100: 317-350. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21829/abm100.2012.39 Links

- CITES. 2025. Appendices. https://cites.org/eng/app/index.php (accessed March 04, 2025). Links

- CONABIO [Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad]. 1997. Provincias biogeográficas de México, escala 1:4000000. México. 1997. Available from: http://www.conabio.gob.mx/informacion/gis/layouts/rbiog4mgw.png . (last accessed 7 November 2024). Links

- Crisp MD, Laffan S, Linder HP, Monro A. 2001. Endemism in the Australian flora. Journal of Biogeography 28: 183-198. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2699.2001.00524.x Links

- Daru BH, le Roux PC, Gopalraj J, Park DS, Holt BG, Greve M. 2019. Spatial overlaps between the global protected areas network and terrestrial hotspots of evolutionary diversity. Global Ecology and Biogeography 28: 737-766. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12888 Links

- de Almeida RF, Alves M, van den Berg C, Pellegrini MOO, Gostel MR, Roque N. 2024. Molecular phylogenetics and historical biogeography of subtribe Ecliptinae (Asteraceae, Heliantheae). Plants 13: 2817. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13192817 Links

- Faith DP. 1992. Conservation evaluation and phylogenetic diversity. Biological Conservation 61: 1-10. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-3207(92)91201-3 Links

- Ferrari L, López-Martínez M, Aguirre-Díaz G, Carrasco-Núñez G. 1999. Space-time patterns of Cenozoic arc volcanism in central Mexico: from the Sierra Madre Occidental to the Mexican Volcanic Belt. Geology 27: 303-306. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1130/0091-7613(1999)027<0303:STPOCA>2.3.CO;2 Links

- Ferrari L, Orozco-Esquivel T, Manea V, Manea M. 2012. The dynamic history of the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt and the Mexico subduction zone. Tectonophysics 522-523: 122-149. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2011.09.018 Links

- Freire SE, Ospina JC, Aagesen L, Espinar LA, Panero JL, Scataglini MA. 2023. Unraveling polyphyly in Flourensia (Asteraceae, Heliantheae, Enceliinae) and the establishment of a New Genus Austroflourensia. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências 95: e20191135. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/0001-3765202320191135 Links

- González-Espinosa M, Ochoa-Gaona S, Ramírez-Marcial N, Quintana-Ascencio PF. 1997. Contexto vegetacional y florístico de la agricultura. In: Parra VMR y Díaz HBM, eds. Los Altos de Chiapas: Agricultura y Crisis Rural. Tomo 1. Los Recursos Naturales. San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas: El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, pp. 85-117. ISBN: 9687355007 Links

- González-Orozco CE, Laffan SW, Miller JT. 2011. Spatial distribution of species richness and endemism of the genus Acacia in Australia. Australian Journal of Botany 59: 601-609. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1071/BT11112 Links

- Graham A. 2018. The role of land bridges, ancient environments, and migrations in assembling the North American flora. Journal of Systematics and Evolution 56: 405-429. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jse.12302 Links

- Gutiérrez-Rodríguez BE, Vásquez-Cruz M, Sosa V. 2022. Phylogenetic endemism of the orchids of Megamexico reveals complementary areas for conservation. Plant Diversity 44: 351-359. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pld.2022.03.004 Links

- Hinton GS, Villaseñor JL, Ortiz E. 2019. The Hintons’ legacy to the knowledge of the flora of Mexico.Botanical Sciences97: 447-538. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17129/botsci.2210 Links

- IUCN. 2023. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2022-2. https://www.iucnredlist.org (accessed 28 January 2024). Links

- Jarzyna MA, Jetz W. 2016. Detecting the multiple facets of biodiversity. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 31: 527-538. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2016.04.002 Links

- Jin Y, Qian H. 2023. U. PhyloMaker: An R package that can generate large phylogenetic trees for plants and animals. Plant Diversity 45: 347-352. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pld.2022.12.007 Links

- Laffan SW, Lubarsky E, Rosauer DF. 2010. Biodiverse, a tool for the spatial analysis of biological and related diversity. Ecography 33: 643-647. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.2010.06237.x Links

- Lu L, Zhao L, Hu H, Liu B, Yang Y, You Y, Peng D, Barrett RL, Chen Z. 2023. A comprehensive evaluation of flowering plant diversity and conservation priority for national park planning in China. Fundamental Research 3: 939-950. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fmre.2022.08.008 Links

- Mandel JR, Dikow RB, Siniscalchi CM, Thapa R, Watson LE, Funk VA. 2019. A fully resolved backbone phylogeny reveals numerous dispersals and explosive diversifications throughout the history of Asteraceae. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116: 14083-14088. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1903871116 Links

- Metcalfe SE, O'Hara SL, Caballero M, Davies SJ. 2000. Records of Late Pleistocene-Holocene climatic change in Mexico -a review. Quaternary Science Reviews 19: 699-721. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-3791(99)00022-0 Links

- Miller JT, Jolley-Rogers G, Mishler BD, Thornhill AH. 2018. Phylogenetic diversity is a better measure of biodiversity than taxon counting.Journal of Systematics and Evolution56: 663-667. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jse.12436 Links

- Mishler BD. 2023. Spatial phylogenetics. Journal of Biogeography 50: 1454-1463. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.14618 Links

- Mishler BD, Guralnick R, Soltis PS, Smith SA, Soltis DE, Barve N, Allen JM, Laffan SW. 2020. Spatial phylogenetics of the North American flora. Journal of Systematics and Evolution 58: 393-405. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jse.12590 Links

- Mishler BD, Knerr N, González-Orozco CE, Thornhill AH, Laffan SW, Miller JT. 2014. Phylogenetic measures of biodiversity and neo-and paleo-endemism in Australian Acacia. Nature Communications 5: 4473. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms5473 Links

- Moraes MD, Panero JL. 2016. A phylogeny of Dimerostemma (Asteraceae, Heliantheae, Ecliptinae) based on the ITS and ETS. Phytotaxa 245: 289-296. DOI: https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.245.4.6 Links

- Moreira GL, Panero JL, Inglis P, Zappi D, Cavalcanti TB. 2023. A time-calibrated phylogeny of Verbesina (Heliantheae-Asteraceae) based on nuclear ribosomal ITS and ETS sequences. Edinburgh Journal of Botany 80: 1-22. DOI: https://doi.org/10.24823/ejb.2023.1953 Links

- Morrone JJ. 2019. Regionalización biogeográfica y evolución biótica de México: encrucijada de la biodiversidad del Nuevo Mundo. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 90: e902980. DOI: https://doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e.2019.90.2980 Links

- Murguía-Romero M, Rojas F. 2001. Biogeografía cuantitativa. In: Llorente-Busquets J, Morrone JJ, eds. Introducción a la Biogeografía en Latinoamérica: Teorías, Conceptos, Métodos y Aplicaciones. México: Facultad de Ciencias Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Pp. 39-47. ISBN: 968-36-9463-2 Links

- Murguía-Romero M, Ortiz E, Serrano-Estrada B, Villaseñor JL. 2023. The Kew’s" World Checklist of Vascular Plants" and its relevance to the knowledge of the flora of Mexico. Botanical Sciences 101: 632-653. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17129/botsci.3223 Links

- Murguía-Romero M, Serrano-Estrada B, Salazar GA, Sánchez-González GE, Palacios UMS, Gernandt DS, Magallón S, Sánchez-Cordero V. 2024. The IBdata Web system for biological collections: Design focused on usability. Biodiversity Informatics 18: 1-12. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17161/bi.v18i.20516 Links

- Nitta JH, Mishler BD, Iwasaki W, Ebihara A. 2022. Spatial phylogenetics of Japanese ferns: Patterns, processes, and implications for conservation. American Journal of Botany 109: 727-745. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/ajb2.1848 Links

- NCBI [National Center for Biotechnology Information]. 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed November 11, 2024) Links

- Panero JL, Jansen RK. 1997. Chloroplast DNA restriction site study of Verbesina (Asteraceae: Heliantheae). American Journal of Botany 84: 382-392. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/2446011 Links

- Panero JL, Jansen RK, Clevinger JA. 1999. Phylogenetic relationships of subtribe Ecliptinae (Asteraceae: Heliantheae) based on chloroplast DNA restriction site data. American Journal of Botany 86: 413-427. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/2656762 Links

- Pinkava DJ. 1967. Biosystematic study of Berlandiera (Compositae). Brittonia 19: 285-298. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/2805783 Links

- Plovanich AE, Panero JL. 2004. A phylogeny of the ITS and ETS for Montanoa (Asteraceae: Heliantheae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 31: 815-821. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2003.10.021 Links

- QGIS Development Team. 2020. QGIS (version 3.14) http://test.qgis.org/html/en/site/forusers/download.html (accessed November 7, 2024). Links

- Qian H, Jin Y. 2021. Are phylogenies resolved at the genus level appropriate for studies on phylogenetic structure of species assemblages?. Plant Diversity 43: 255-263. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pld.2020.11.005 Links

- Qian H, Qian S, Zhang J, Kessler M. 2024. Effects of climate and environmental heterogeneity on the phylogenetic structure of regional angiosperm floras worldwide. Nature Communications 15: 1079. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-45155-9 Links

- R Core Team. 2024. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed November 7, 2024) Links

- Redonda-Martínez R. 2022. Tribus de Asteraceae en México, morfología y clave de identificación. Acta Botanica Mexicana 129. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21829/abm129.2022.2122 Links

- Rivera P, Villaseñor JL, Terrazas T, Panero JL. 2021. The importance of the Mexican taxa of Asteraceae in the family phylogeny. Journal of Systematics and Evolution 59: 935-952. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jse.12681 Links

- Robinson HE. 1981. A revision of the tribal and subtribal limits of the Heliantheae (Asteraceae). Smithsonian Contributions to Botany 54: 1-59. Links

- Rodrigues AS, Gaston KJ. 2002. Maximising phylogenetic diversity in the selection of networks of conservation areas. Biological Conservation 105: 103-111. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3207(01)00208-7 Links

- Rodríguez P, Villalobos F, Sánchez-Barradas A, Correa-Cano ME. 2017. La macroecología en México: historia, avances y perspectivas. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 88: 52-64. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmb.2017.10.006 Links

- Rosauer DF, Laffan SW, Crisp MD, Donnellan SC, Cook LG. 2009. Phylogenetic endemism: a new approach to identifying geographical concentrations of evolutionary history. Molecular Ecology 18: 4061-4072. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04311.x Links

- Rzedowski J. 1978. Vegetación de México. DF, México: Limusa. ISBN: 968-18-0002-8 Links

- Schilling EE, Panero JL. 2002. A revised classification of subtribe Helianthinae (Asteraceae: Heliantheae). I. Basal lineages. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 140: 65-76. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1095-8339.2002.00079.x Links

- Schilling EE, Panero JL. 2010. Transfers to Simsia and description of Davilanthus, a new genus of Asteraceae (Heliantheae). Brittonia 62: 309-320. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12228-010-9129-1 Links

- Schilling EE, Panero JL. 2011. A revised classification of subtribe Helianthinae (Asteraceae: Heliantheae) II. Derived lineages. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 167: 311-331. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8339.2011.01172.x Links

- SEMARNAT [Secretaría del Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales]. 2019. Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010, Protección ambiental - Especies nativas de México de flora y fauna silvestres - Categorías de riesgo y especificaciones para su inclusión, exclusión o cambio - Lista de especies en riesgo. Diario Oficial de la Federación. 2da Sección, 30 de diciembre de 2010. https://www.transparencia.cdmx.gob.mx/storage/app/uploads/public/61c/622/2f8/61c6222f8af30531369273.pdf (accessed March 04, 2025). Links

- Smith SA, Brown JW. 2018. Constructing a broadly inclusive seed plant phylogeny. American Journal of Botany 105: 302-314. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/ajb2.1019 Links

- SNIB [Sistema Nacional de Información sobre Biodiversidad]. 2024. Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, México. https://www.snib.mx/ (accessed November 26, 2024). Links

- Sosa V, De-Nova JA, Vásquez-Cruz M. 2018. Evolutionary history of the flora of Mexico: Dry forests cradles and museums of endemism. Journal of Systematics and Evolution 56: 523-536. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jse.12416 Links

- Soto-Trejo F, Robles F, Lira R, Sánchez-González LA, Ortiz E, Dávila P. 2024. The evolution of paleo-and neo-endemic species of Cactaceae in the isolated Valley of Tehuacán-Cuicatlán, Mexico. Plant Ecology and Evolution 157: 42-54. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5091/plecevo.110352 Links

- Stuessy TF. 1990. Plant Taxonomy. New York, USA: Columbia University Press. ISBN: 978-0-231-14712-5 Links

- Suárez-Mota ME, Villaseñor JL, López-Mata L. 2017. Dominios climáticos de la Sierra Madre Oriental y su relación con la diversidad florística. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 88: 224-233. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmb.2017.01.020 Links

- Susanna A, Baldwin BG, Bayer RJ, Bonifacino JM, Garcia-Jacas N, Keeley SC, Mandel JR, Ortiz S, Robinson H, Stuessy TF. 2020. The classification of the Compositae: A tribute to Vicki Ann Funk (1947-2019). Taxon 69: 807-814. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/tax.12235 Links

- Thiers BM. 2024. Index Herbariorum. https://sweetgum.nybg.org/science/ih/ Links

- Tomasello S, Stuessy TF, Oberprieler C, Heubl G. 2019. Ragweeds and relatives: Molecular phylogenetics of Ambrosiinae (Asteraceae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 130: 104-114. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2018.10.005 Links

- Tuomisto H. 2010. A consistent terminology for quantifying species diversity? Yes, it does exist. Oecologia 164: 853-860. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-010-1812-0 Links

- Ulloa-Ulloa C, Acevedo-Rodríguez P, Beck S, Belgrano MJ, Bernal R, Berry PE, Brako L, Celis M, Davidse G, Forzza RC, Gradstein SR, Hokche O, León B, León-Yanez S, Magill RE, Neill DA, Nee M, Raven PH, Stimmel H, Strong MT, Villaseñor JL, Zarucchi JL, Zuloaga FO, Jørgensen PM. 2017. An integrated assessment of the vascular plant species of the Americas. Science 358: 1614-1617. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao0398 Links

- Villaseñor JL. 1990. The genera of Asteraceae endemic to Mexico and adjacent regions. Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Floristic Botany 12: 685-692. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5642/aliso.19901204.04 Links

- Villaseñor JL. 1991. Las Heliantheae endémicas a México: una guía hacia la conservación. Acta Botanica Mexicana 15: 29-46. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21829/abm15.1991.619 Links

- Villaseñor JL. 2004. Los géneros de plantas vasculares de la flora de México. Boletín de la Sociedad Botánica de México 73: 105-135. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17129/botsci.1694 Links

- Villaseñor JL. 2010. El bosque húmedo de montaña en México y sus plantas vasculares: Catálogo florístico-taxonómico. DF, México: Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. ISBN: 978-607-02-1557-5 Links

- Villaseñor JL. 2018. Diversidad y distribución de la familia Asteraceae en México. Botanical Sciences 96: 332-358. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17129/botsci.1872 Links

- Villaseñor JL, Dávila P, Chiang F. 1990. Fitogeografía del valle de Tehuacán-Cuicatlán. Botanical Sciences 50: 135-149. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17129/botsci.1381 Links

- Villaseñor JL, Encina-Domínguez JA, Estrada-Castillón E, Hinton GS, Mora-Olivo A, Ortiz E, Villarreal-Quintanilla JA. 2023a. Diversidad florística de la región noreste de México, estados de Coahuila, Nuevo León y Tamaulipas. Botanical Sciences 101: 1301-1319. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17129/botsci.3328 Links

- Villaseñor JL, Ibarra-Manríquez G, Meave JA, Ortiz E. 2005. Higher taxa as surrogates of plant biodiversity in a megadiverse country. Conservation Biology 19: 232-238. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00264.x Links

- Villaseñor JL, Maeda P, Rosell JA, Ortiz E. 2007. Plant families as predictors of plant biodiversity in Mexico. Diversity and Distributions 13: 871-876. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4642.2007.00385.x Links

- Villaseñor JL, Meave JA. 2022. Floristics in Mexico today: insights into a better understanding of biodiversity in a megadiverse country. Botanical Sciences 100(SPE): 14-33. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17129/botsci.3050 Links

- Villaseñor JL, Ortiz E, Beutelspacher CR, Gómez-López JA. 2013. La familia Asteraceae en el municipio de San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas, México. Lacandonia 7: 31-55. Links

- Villaseñor JL, Ortiz E, Delgadillo-Moya C, Juárez D. 2020. The breadth of the Mexican Transition Zone as defined by its flowering plant generic flora. Plos One 15: e0235267. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235267 Links

- Villaseñor JL, Ortiz E, Juárez D. 2021. Transition zones and biogeographic characterization of endemism in three biogeographic provinces of central Mexico. Botanical Sciences 99: 938-954. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17129/botsci.2768 Links

- Villaseñor JL, Ortiz E. 2022. A phytogeographic assessment of the Sierra Madre Oriental physiographic province, Mexico. Botanical Sciences 100: 1102-1123. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17129/botsci.3086 Links

- Villaseñor JL, Ortiz E, Hernández-Flores, MM. 2023b. The vascular plant species endemic or nearly endemic to Puebla, Mexico. Botanical Sciences 101: 1207-1221.DOI: https://doi.org/10.17129/botsci.3299 Links

- Villaseñor JL, Ortiz E, Murguía-Romero M. 2024. The rarest of rarities in the flora of Mexico.Botanical Sciences102: 1300-1317. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17129/botsci.3498 Links

- Villaseñor JL, Téllez-Valdés O. 2004. Distribución potencial de las especies del género Jefea (Asteraceae) en México. Anales del Instituto de Biología. Serie Botánica 73: 205-220. Links

- Whittaker RH. 1972. Evolution and measurement of species diversity. Taxon 21: 213-251. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/1218190 Links

- Zanne AE, Tank DC, Cornwell WK, Eastman JM, Smith SA, FitzJohn RG, McGlinn DJ, O’Meara BC, Moles AT, Reich PB, Royer DL, Soltis DE, Stevens PF, Westoby M, Wright IJ, Aarssen L, Bertin RI, Calaminus A, Govaerts R, Hemmings F, Leishman MR, Oleksyn J, Soltis PS, Swenson NG, Warman L, Beaulieu, J.M. 2014. Three keys to the radiation of angiosperms into freezing environments. Nature 506: 89-92. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12872 Links

- Zhang C, Huang CH, Liu M, Hu Y, Panero JL, Luebert F, Go T, Ma H. 2021. Phylotranscriptomic insights into Asteraceae diversity, polyploidy, and morphological innovation. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 63: 1273-1293. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/jipb.13078 Links

- Zhang G, Yang J, Zhang C, Jiao B, Panero JL, Cai J, Zhang Z-R, Gao L-M, Gao T, Ma, H. 2024. Nuclear phylogenomics of Asteraceae with increased sampling provides new insights into convergent morphological and molecular evolution. Plant Communications 5: 100851 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xplc.2024.100851 Links