Articles

Cuba y Soviet Union: Trade Pattern Pitfalls (1970-1988)

Cuba y la Unión Soviética: trampas del patrón comercial (1970-1988)

Terentev, Pavel1*

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3405-4942

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3405-4942

Vavichkina, Tatiana2

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3474-5820

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3474-5820

Vlasova, Yulia2

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4311-3403

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4311-3403

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3405-4942

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3405-4942Vavichkina, Tatiana2

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3474-5820

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3474-5820Vlasova, Yulia2

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4311-3403

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4311-3403-

Publication dates-

January 17, 2025

Sep-Dec , 2023

- Article in PDF

- Article in XML

- Automatic translation

- Send this article by e-mail

- Share this article +

Abstract

This article analyzes the interaction between the Soviet Union and Cuba, the bilateral trade in sugar and nickel ores as well as direct assistance of the USSR to the Castro regime. The scholars investigate the dependence of the Cuban economy on economic cooperation with the Soviet Union and indicate that the pattern of bilateral trade was extremely harmful to Cuba since Havana took advantage of the artificial steady demand for the main components of Cuban exports from the USSR and other Comecon countries. The researchers point out that such a model of trade was one of the key factors that doomed the State’s economy to a severe economic crisis of the 1990-s and left Cuba behind other Latin American economies even the extremely depended on a particular resource export, ones such as Chile and Venezuela in terms of economic development.

Key words:

Soviet and Cuban trade, Cuban sugar industry, Soviet economic assistance

Clasificación JEL::

N16, N56, N46, N96

Introduction

It is an extremely popular assumption that partnership between the Soviet Union and the Republic of Cuba after the Castro brothers coming to power in 1959 was mutually beneficial. It allowed the Soviet Union to significantly strengthen its influence in Latin America and the Caribbean, increase the collective potential of the Socialist bloc in the world and obtain new opportunities to defend its interests in regional conflicts, for example, with the help of Cuban militants participating in hostilities in Angola (Valenta, 1981). At the same time, Cuba is usually thought to have benefited from trade with the USSR and other Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (here forth Comecon) states with the economic cooperation with the Socialist bloc being perceived as a kind of lifesaver amid the United States economic blockade (Stroganov, 2017). However, one fact tends to be ignored. The economic cooperation between the USSR and Cuba was a form of assistance from the Soviet Union to its junior partner, a process of buying influence over Havana and ensuring the stable Cuban economic growth at the expense of the well-being of inhabitants of the Soviet Union as well as other countries of the Comecon. Eventually, such a pattern of interaction, especially the artificial trade conditions, perverted the Cuban leaders and doomed the economy to a hard transition period after the collapse of the Socialist bloc.

-

Valenta, 1981The Soviet-Cuban Alliance in Africa and the CaribbeanThe World Today, 1981

-

Stroganov, 2017Latin America: Pages of 20th Century History, 2017

There is a plethora of research devoted to analyzing Soviet-Cuban economic relations. For instance, I. Wiesel (1968) compares the roles of the USA in the Cuban economy before 1959 with the Soviet one after the revolution, Cole Blasier (2002) argues that Moscow’s assistance was the key factor which let Castro regime survive, while Brian H. Pollitt (2004) analyzes the causes of the Cuban economic crisis after the collapse of the USSR. Moreover, several authors directly examine the Soviet assistance to Cuba, its various aspects and forms. Robert S. Walters (1966) analyzes how the Soviet Union used to re-export Cuban sugar to other countries, Brian H. Pollitt y Hagelberg (1994) and David Lehmann (1979) investigate the Cuban economy dependence on Soviet purchases of sugar, nickel and other exported goods at preferential prices, while Susan Eckstein (1980) stresses that partnership with the USSR deprived Cuba of an opportunity to easily export its sugar to Capitalist states thus affecting its economic development.

-

I. Wiesel (1968)Cuban Economy and the RevolutionActa Oeconomica, 1968

-

Cole Blasier (2002)Soviet Impacts on Latin AmericaRussian History, 2002

-

Brian H. Pollitt (2004)The Rise and Fall of the Cuban Sugar EconomyJournal of Latin American Studies, 2004

-

Robert S. Walters (1966)Soviet Economic Aid to Cuba: 1959–1964Royal Institute of International Affairs, 1966

-

Brian H. Pollitt y Hagelberg (1994)The Cuban Sugar Economy in the Soviet Era and AfterCambridge Journal of Economics, 1994

-

David Lehmann (1979)The Cuban economy in 1978Cambridge Journal of Economics, 1979

-

Susan Eckstein (1980)Capitalist constraints on Cuban socialist developmentComparative Politics, 1980

However, the scientific novelty of this paper consists in the fact that the researchers apply qualitative methods of analysis and demonstrate that such economic cooperation left Cuba behind a number of other developing Latin American countries, deprived the Cuban leaders of a necessity to timely conduct economic reforms and adjust to changing economic reality, let them parasite on the unlimited desire of Moscow to expand its political sphere of interests which itself led to the demise of the Soviet Empire. Thus, Havana did not try to realize complex economic transformations, to diversify exports and reduce the dependence on sugar or nickel ore sales like Pinochet’s Chile shortened the dependence of its economy on copper exports. The Cuban leaders merely enjoyed the benefits of being a recipient of Soviet assistance. As for Moscow, the USSR had to buy a great amount of Cuban goods (sugar and nickel ores) at preferential prices that it did not need devastating its economic resources.

The purpose of this work is to analyze the experience of Soviet-Cuban economic cooperation after the Castro regime coming to power. The research places special emphasis on the Soviet purchases of the main components of Cuban exports: sugar and nickel ores, and give a conclusion on the feasibility of such a trade pattern comparing the Cuban experience to the one of other export-oriented Latin American economies.

The objectives of the study are as follows to analyze the sugar trade between Cuba and the USSR, as well as between Cuba and Socialist and Capitalist countries, the trade in nickel ores between Cuba and the USSR, the subsidy of prices for Cuban sugar by the USSR, to compare economic development indicators of Cuba and other Latin American countries, to determine whether the trade with the USSR was the key driver of the Cuban economic growth and to compare the economic policy of the Castro regime with the one of such resource depending states as Chile and Venezuela.

Methodology y data

This research is a historical case study based on qualitative methods of analysis. They include the content and narrative analysis as well as a historic analysis of the economic cooperation between the Soviet Union and Cuba (1970-1988) and the examination of the Cuban economic performance throughout the 20th century in comparison to the economic development of other Latin American countries. The data used in this research comprises historic macroeconomic indicators from Maddison Project Database, version 2020., Bolt and Zanden (2020), statistics from Macrotrends (1970-2020), Cuba. Member of COMECON (1984). Also, the scholars analyze Cuban sugar and nickel industries and trade indicators from Soviet Union-Cuba: Economic cooperation (70-80s) by Bekarevich and Kukharev (1990) and US Bureau of Mines Mineral Yearbooks, 1932-1993. What is more, it is analyzed a plethora of research devoted to Cuban history, economy, trade relations as well as the interaction between Moscow and Havana.

-

Maddison Project Database, version 2020., Bolt and Zanden (2020)Maddison style estimates of the evolution of the world economy. A new 2020 update, 2020

-

Macrotrends (1970-2020), 1970

-

Cuba. Member of COMECON (1984)Council for Mutual Economic Assistance [Comecon] Secretariat, 1984

-

Bekarevich and Kukharev (1990)Soviet Union-Cuba: Economic cooperation (70-80s), 1990

Reasons for the Soviet-Cuban rapprochement

Economic cooperation between the USSR and Cuba, which had been virtually non-existent during the years of Fulgencio Batista’s rule on the island (1952-1959), was restored after the victory of Castro’s revolutionary forces. However, the Cuban leaders did not intend to break all the ties with Washington. The best illustration of that is the fact that soon after the Castro regime coming to power in early January 1959 the Cuban leader himself headed to the USA in April 1959. Formally, this was Fidel Castro’s unofficial visit at the invitation of the American Society of Newspaper Editors. But it is unlikely that such a choice of the first trip was made accidentally especially considering that during his stay in the USA Castro met with the US vice president Richard Nixon and acting secretary of State Christian Herter (Andrew, 2013).

-

Andrew, 2013Fidel Castro visits the U.S., April 15, 1959, 2013

Also, the Cuban leader’s decision to intensify economic interaction with Moscow, as well as their desire to follow the Socialist model of development, which was announced by Fidel Castro in 1961 (Martynov, 2019), were only an attempt to find a way out of the economic blockade and diplomatic isolation. But it is important to understand that Washington imposed embargo as well as asserted political pressure on the island trying to isolate the Castro regime only after the beginning of the active nationalization of the property of not only Cubans, but also foreign owners, including US citizens (Allison, 1961). So, there is no denying the fact that Havana had to search for new trading partners responding to the US actions. Still, such a reaction of the White House was primary dictated by the desire to defend the rights of the US citizens and corporations. Therefore, it is fair to claim that the only one guilty in the stalemate where Cuba found itself after 1959 was its regime with extremely populist rhetoric aimed at securing support of the poor by the "take everything and share" nationalization campaign.

-

Martynov, 2019History of international relations of Latin America and the Caribbean (19th-early 21st Century), 2019

-

Allison, 1961Cuba’s Seizures of American BusinessAmerican Bar Association Journal, 1961

The rapprochement with the USSR was a lifesaver for the Castro regime. On the one hand, the country received protection from American interventions (which became especially important after the defeat of the mercenaries on playa Girón in April 1961). On the other hand, Cuba obtained a generous donor who would buy the main components of Cuban exports (sugar and nickel ores), would assist the Cuban dictator in carrying out economic reforms and provide Cuba with qualified specialists and technologies in order to keep Cuba in its sphere of influence.

Economic cooperation between the USSR and Cuba began with the conclusion of an agreement on the purchase of Cuban sugar and the granting of a loan of 100 million dollars to Cuba at 2.5% annually in February 1960 (Martynov, 2019). The USSR quickly became the key Cuban trading partner and together with other Socialist countries turned out to be the main buyer of Cuban sugar, nickel ores, rum and tobacco. What is more, these purchases were often carried out at preferential prices. As for Cuban sugar, in the period from 1960 to 1985, the total amount of Soviet sugar subsidies exceeded 22 billion dollars (Perez-Lopez, 1988). Therefore, we can fully agree with Jorge F. Perez-Lopez, who in 1988 noted that "such an increase in prices for Cuban products allowed Cuba to significantly correct the trade balance with the USSR, but at the same time led to the fact that the rate of return for investment in the sugar industry was artificially inflated, which subsequently further aggravated the imbalance in the Cuban economy in favor of the sugar industry" (Perez-Lopez, 1988).

-

Martynov, 2019History of international relations of Latin America and the Caribbean (19th-early 21st Century), 2019

-

Perez-Lopez, 1988Cuban-Soviet Sugar Trade: Price and Subsidy IssuesBulletin of Latin American Research, 1988

-

Perez-Lopez, 1988Cuban-Soviet Sugar Trade: Price and Subsidy IssuesBulletin of Latin American Research, 1988

Also, it should be considered that the Cuban pro-Soviet orientation also allowed Havana to take advantage of trading with other Socialist states. In 1972, Cuba became a member of the Comecon. It could have provided the country with an opportunity to start profitable cooperation with new partners, get a chance to neutralize the negative consequences of the US economic blockade and create the necessary conditions for high-quality economic transformations.

Features of Soviet-Cuban cooperation

Examining the Castro regime success in the economic sphere, which was largely associated with the beginning of active cooperation with the USSR and the Comecon countries, it is impossible to deny the fact that the infant mortality rate on the island has significantly decreased (in 1972, this figure was 28.1 deaths per 1 000 infants; in 1990, 10.9 deaths per 1 000 infants) (World Bank, 1972-1900a), the average life expectancy has increased (70.787 years in 1972, 74.638 years in 1990) (World Bank, 1972-1900b), and the country’s economy really demonstrated a steady growth rate of gross domestic product (here forth gdp) per capita (see table 1).

-

World Bank, 1972-1900aInfant Mortality Rate for Cuba, 1972

-

World Bank, 1972-1900bLife Expectancy at Birth, Total for Cuba, 1972

Table 1

Average gdp growth (percentage) of Cuba, and selected Latin American countries

Average gdp growth (percentage) of Cuba, and selected Latin American countries

| Cuba | 2.05 | 4.58 | 2.43 | -0.41 |

| Argentina | 4.41 | 2.96 | -0.81 | 4.82 |

| Chile | 4.12 | 2.95 | 3.17 | 5.72 |

| Venezuela | 6.06 | 3.91 | 0.76 | 2.68 |

However, the words "steady and stable" hide an extremely unpleasant picture, namely, the fact that this "stability" was ensured by the serious trade deficit of the country. It was observed for most of the history of trade between Cuba and the Socialist countries after the Castro regime coming to power. The Comecon countries, and especially the USSR, were not just the main suppliers of machinery, tools, equipment, and high-tech products to the island, but were also the main importers of the two main components of Cuban exports, namely sugar and nickel (see tables 2 and 3). It is noteworthy that over the years, the dependence of the Cuban economy on trade with the USSR only strengthened. Between 1970 and 1988, the volume of bilateral trade increased by more than seven times (see table 2). Furthermore, the USSR was the largest sugar producer in the whole world in the 1970-s being surpassed only by the European Community which included leading European economies such as France, Western Germany and Italy (see table 4). At the same time, the USSR was the second largest producer of nickel surpassed only by Canada (see figure 1). Therefore, it is extremely doubtable that the Soviet economy as well as other Comecon states needed so much Cuban nickel and cane sugar since the USSR itself was one of the leading exporters of these goods (Hoff & Lawrence, 1985; Valetov, 2015).

-

Hoff & Lawrence, 1985Implications of World Sugar Markets, Policies, and Production Costs for U.S. Sugar, 1985

-

Valetov, 2015Non-Ferrous Metals of the USSR: Their Production and Trade in 1917-1966ISTORIYA, 2015

Table 2

Soviet-Cuban trade (million rubles)

Soviet-Cuban trade (million rubles)

| 1960 | 160.6 | 67.2 | 93.4 | -26.2 |

| 1970 | 1 045.0 | 580.0 | 465.0 | 115.0 |

| 1971 | 890.9 | 602.0 | 288.9 | 313.1 |

| 1972 | 821.7 | 616.2 | 205.5 | 410.7 |

| 1973 | 1 109.6 | 679.1 | 430.5 | 248.6 |

| 1974 | 1 642.3 | 926.1 | 716.2 | 209.9 |

| 1975 | 2 589.0 | 1 141.3 | 1 447.7 | -306.4 |

| 1976 | 2 872.1 | 1 351.3 | 1 520.8 | -169.5 |

| 1977 | 3 452.1 | 1 634.9 | 1 817.2 | -182.3 |

| 1978 | 4 169.0 | 1 946.7 | 2 222.3 | -275.6 |

| 1979 | 4 249.2 | 2 113.2 | 2 136.0 | -22.8 |

| 1980 | 4 266.0 | 2 288.4 | 1 977.6 | 310.8 |

| 1981 | 4 807.0 | 2 754.5 | 2 052.5 | 720.0 |

| 1982 | 5 840.5 | 3 131.4 | 2 709.1 | 422.3 |

| 1983 | 6 093.2 | 3 399.9 | 2 693.3 | 706.6 |

| 1984 | 7 216.1 | 3 752.2 | 3 463.9 | 288.3 |

| 1985 | 8 017.5 | 3 877.4 | 4 140.1 | -262.7 |

| 1986 | 7 602.6 | 3 802.4 | 3 800.2 | 2.2 |

| 1987 | 7 558.6 | 3 731.3 | 3 827.3 | -96.0 |

| 1988 | 7 563.6 | 3 726.8 | 3 836.8 | -110.0 |

Table 3

Trade Turnover of the Republic of Cuba with Comecon Countries, million pesos

Trade Turnover of the Republic of Cuba with Comecon Countries, million pesos

| 1970 | 1975 | 1980 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 677.6 | 825.5 | 1 503.1 | 1 888.3 | 1 499.5 | 3 387.8 | 2 654.6 | 3 385.2 | 6 039.8 |

| Bulgaria | 28.8 | 23.3 | 52.1 | 75.8 | 84.1 | 159.9 | 111.4 | 145.0 | 256.4 |

| Hungary | 3.5 | 4.9 | 8.4 | 19.9 | 19.5 | 39.4 | 27.5 | 48.8 | 76.3 |

| German Democratic Republic | 48.8 | 50.0 | 98.8 | 70.4 | 76.2 | 146.6 | 121.4 | 161.4 | 282.8 |

| Mongolia | - | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.4 |

| Poland | 5.4 | 3.4 | 8.8 | 17.8 | 15.4 | 33.2 | 35.9 | 68.3 | 104.2 |

Table 4

Average Share of World Production of Centrifugal Sugar, by Country and Region

Average Share of World Production of Centrifugal Sugar, by Country and Region

| European Community | 12.8 | 14.2 | 15.2 |

| Soviet Union | 11.9 | 9.5 | 7.8 |

| Other Europe | 9.3 | 9.6 | 9.7 |

| Brazil | 8.0 | 8.7 | 9.5 |

| Other South America | 6.0 | 5.8 | 5.3 |

| India | 5.5 | 6.5 | 7.5 |

| China | 4.3 | 3.0 | 3.8 |

| Japan | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.9 |

| Philippines | 2.9 | 3.0 | 2.5 |

| Thailand | 0.9 | 2.1 | 2.3 |

| Other Asia | 4.3 | 4.2 | 3.9 |

| Cuba | 7.8 | 8.1 | 8.1 |

| Mexico | 3.5 | 3.3 | 3.0 |

| Other Central America | 4.1 | 4.0 | 3.6 |

| United States | 7.3 | 6.6 | 5.8 |

| Other North America | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Australia | 3.6 | 3.6 | 3.7 |

| Other Oceania | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| Africa | 6.8 | 6.7 | 6.9 |

Thumbnail

Figure 1

Selected Countries: Share of Nickel Production of Total World Nickel Production (1971-1988) (percentage)

Selected Countries: Share of Nickel Production of Total World Nickel Production (1971-1988) (percentage)

Apart from the trade with the USSR and other Comecon countries, Cuba was a subject to the Soviet direct aid programs. Since 1970, the share of Cuba in the total volume of the USSR’s assistance to foreign countries under existing agreements steadily increased, and in just less than 20 years (1970-1988) it more than doubled (from 3.78% in 1970 to 8.56% in 1988). In the end, it was Cuba that became the third Socialist country in terms of the share of total economic assistance provided by the USSR (after Bulgaria and Mongolia), overtaking not only North Korea, but also the closest neighbors of the USSR: German Democratic Republic, Poland, or Romania. It is also remarkable that the volume of assistance provided to Cuba by the Soviet Union was almost constantly growing, which only indicates the increasing dependence of the Cuban economy on the Soviet Union (see table 5). So, it is fair to conclude that the above-mentioned achievements of the Castro regime in terms of economic development was driven by both direct economic aid and indirect assistance (stable demand for Cuban exports and preferential prices) by the USSR and other Comecon countries.

Table 5

The Share of the Socialist Countries in the Total Volume of the USSR’s Assistance to Foreign Countries Under the Existing Agreements (percentage)

The Share of the Socialist Countries in the Total Volume of the USSR’s Assistance to Foreign Countries Under the Existing Agreements (percentage)

| All Socialist countries | 63.24 | 59.26 | 59.52 | 61.06 | 64.57 | 64.47 | 61.06 |

| Bulgaria | 13.39 | 12.13 | 8.89 | 10.70 | 10.44 | 10.33 | 9.78 |

| Hungary | 2.67 | 2.83 | 3.57 | 3.07 | 3.15 | 3.08 | 2.92 |

| German Democratic Republic | 5.72 | 6.64 | 6.28 | 4.80 | 4.55 | 5.37 | 4.99 |

| Cuba | 3.78 | 3.97 | 5.96 | 6.66 | 9.16 | 9.06 | 8.56 |

| Mongolia | 6.64 | 5.54 | 11.02 | 8.58 | 10.36 | 10.23 | 9.70 |

| Poland | 4.78 | 5.56 | 4.71 | 3.75 | 4.51 | 4.10 | 4.26 |

| Romania | 5.44 | 3.63 | 3.10 | 2.68 | 2.51 | 2.50 | 2.38 |

| Czechoslovakia | 1.40 | 2.22 | 3.80 | 3.84 | 3.79 | 3.97 | 3.59 |

| Socialist Republic of Vietnam | 2.50 | 3.90 | 3.51 | 4.52 | 5.88 | 5.81 | 5.49 |

| Democratic People’s Republic of Korea | 4.06 | 2.73 | 1.89 | 3.84 | 3.55 | 3.47 | 3.28 |

| Yugoslavia | 1.52 | 3.19 | 2.34 | 2.45 | 2.32 | 2.23 | 2.12 |

| Other Socialist countries | 11.34 | 6.92 | 4.45 | 6.17 | 4.35 | 4.32 | 3.99 |

Sugar production y export

The quantitative indicators of both the sugar production on the island and the changes in the export of Cuban sugar to the world market can serve as an excellent indicator, which shows that during all the years of active cooperation between Cuba and the Socialist countries, the dependence of the Cuban economy on the sugar industry only increased. If we consider in detail the state of the Cuban sugar industry, it is fair to note the fact that both the production of sugar on the island and the share of Cuba in the world export of this product have also grown during the years of the Castro regime. In 1971, the island produced about 6 000 000 tons of sugar, but, in 1988, this figure exceeded 8 000 tons, although the share of world production slightly decreased (from 8.04% in 1971 to 7.75% in 1988). The export figures are similar: total exports increased by just under 1.5 million tons over 17 years, while Cuba’s share of world sugar exports decreased only a little from 26.3% in 1971 to 25.71% in 1988 (see table 6). Thus, there can be drawn one conclusion, the Cuban leaders not just failed to reduce the degree of dependence of the country’s economy on sugar exports, they did not strive to achieve this goal at all. They were just taking advantage of the Cuban status of one of the world’s main sugar exporters.

Table 6

Cuba’s Share of World Sugar Production and Exports, tons

Cuba’s Share of World Sugar Production and Exports, tons

| 1971 | 73 959 434 | 43 035 252 | 5 950 029 | 8.04 | 13.82 | 20 957 034 | 5 510 860 | 26.3 |

| 1972 | 75 744 360 | 43 443 992 | 4 687 802 | 6.18 | 10.79 | 21 782 256 | 4 139 556 | 19.0 |

| 1973 | 78 012 866 | 45 993 089 | 5 382 548 | 6.90 | 11.70 | 22 422 655 | 4 797 377 | 21.39 |

| 1974 | 78 853 394 | 48 916 951 | 5 925 850 | 7.51 | 12.11 | 21 919 253 | 5 491 247 | 25.06 |

| 1975 | 81 588 989 | 49 613 319 | 6 427 382 | 7.88 | 12.95 | 20 314 625 | 5 743 711 | 28.27 |

| 1976 | 82 400 222 | 51 167 448 | 6 150 797 | 7.46 | 12.02 | 22 793 536 | 5 763 652 | 25.28 |

| 1977 | 90 344 882 | 54 609 848 | 6 953 284 | 7.70 | 12.73 | 28 459 268 | 6 238 162 | 21.92 |

| 1978 | 90 832 258 | 55 047 744 | 7 661 546 | 8.43 | 13.91 | 25 071 843 | 7 231 219 | 28.84 |

| 1979 | 89 327 189 | 54 798 204 | 7 799 968 | 8.73 | 14.23 | 25 085 118 | 7 269 429 | 28.98 |

| 1980 | 84 514 147 | 51 502 835 | 6 805 235 | 8.05 | 13.21 | 26 831 757 | 6 191 074 | 23.07 |

| 1981 | 92 764 046 | 57 025 252 | 7 925 634 | 8.54 | 13.89 | 29 142 380 | 7 071 445 | 24.26 |

| 1982 | 101 809 793 | 64 527 140 | 8 039 479 | 7.89 | 12.45 | 30 427 334 | 7 734 283 | 25.41 |

| 1983 | 96 901 194 | 60 658 478 | 7 460 225 | 7.69 | 12.29 | 28 981 442 | 6 792 093 | 23.34 |

| 1984 | 99 208 975 | 61 891 578 | 7 783 409 | 7.84 | 12.57 | 29 497 212 | 7 016 510 | 24.62 |

| 1985 | 98 155 330 | 61 274 245 | 7 889 240 | 8.03 | 12.87 | 27 750 140 | 7 209 008 | 25.97 |

| 1986 | 100 280 548 | 62 766 640 | 7 467 415 | 7.44 | 11.89 | 27 199 701 | 6 702 588 | 24.64 |

| 1987 | 104 457 035 | 65 570 465 | 7 231 773 | 6.92 | 11.02 | 28 294 953 | 6 482 135 | 22.90 |

| 1988 | 104 703 110 | 66 476 863 | 8 119 045 | 7.75 | 12.21 | 27 142 038 | 6 978 222 | 25.71 |

The indicators of the Cuban sugar export to the USSR are even more depressing: within 17 years from 1971 to 1988, the USSR finally turned into the main and uncontested buyer of the Cuban sugar, which is unlikely to be in a great demand among Soviet people. Since the mid-1970s it was the Soviet Union that had become the importer of more than half of all sugar exported by Cuba, while the export of Cuban sugar itself had more than doubled in 16 years from 1.5 million tons in 1971 to 3.76 million tons of sugar in 1987. Moreover, with the beginning of the Soviet Perestroika in March 1985 the export of Cuban sugar to the USSR only continued to grow (see table 7; figure 2).

Table 7

Supplies of Raw Sugar by the Republic of Cuba to the USSR

Supplies of Raw Sugar by the Republic of Cuba to the USSR

| 1971 | 5 511 | 1 536 | 185 642 | 27.87 |

| 1972 | 4 139 | 1 101 | 131 465 | 26.60 |

| 1973 | 4 797 | 1 603 | 313 058 | 33.42 |

| 1974 | 5 491 | 1 856 | 610 782 | 33.80 |

| 1975 | 5 744 | 2 964 | 1 344 312 | 51.60 |

| 1976 | 5 764 | 3 068 | 1 397 830 | 53.23 |

| 1977 | 6 238 | 3 652 | 1 675 346 | 58.54 |

| 1978 | 7 197 | 3 797 | 2 117 209 | 52.76 |

| 1979 | 7 199 | 3 707 | 2 037 903 | 51.49 |

| 1980 | 6 170 | 2 647 | 1 857 934 | 42.90 |

| 1981 | 7 055 | 3 090 | 1 825 665 | 43.80 |

| 1982 | 7 727 | 4 224 | 2 476 334 | 54.66 |

| 1983 | 7 011 | 2 966 | 2 408 314 | 42.30 |

| 1984 | 7 007 | 3 508 | 3 209 285 | 50.06 |

| 1985 | 7 206 | 3 685 | 3 312 053 | 51.14 |

| 1986 | 6 697 | 3 861 | 3 091 475 | 57.65 |

| 1987 | 6 479 | 3 750 | 2 937 183 | 57.88 |

| 1988 | - | 3 004 | 2 613 296 | - |

| 1989 | - | 3 468 | 2 596 095 | - |

Thumbnail

Figure 2

Cuban Sugar Exports to the USSR, thousand tons

Cuban Sugar Exports to the USSR, thousand tons

What is more, it is remarkable that such an increase of Cuban sugar exports did not match the world sugar price changes. For instance, the remarkable increase in Cuban exports of 1974-1977 and the one of 1980-1985 took place amid a dramatic decrease in average annual world price. On the contrary, the rapid rise of average world sugar prices of 1978-1980 was accompanied by a significant fall in Cuban sugar exports to the USSR. These cases may be considered as an illustration of the Soviet assistance to Cuba: amid world sugar prices fall Moscow used to intensify purchases of Cuban key export component, while amid the world sugar price rise the volume of sugar supplies to the USSR decreased. Still, it does match the situation of 1971-1974. Also, it should be considered that average annual world sugar prices are calculated in current US dollars and do not account for inflation but anyway the overall picture is unlikely to significantly alter (see figures 2 and 3).

Thumbnail

Figure 3

Average World Sugar Price, USD per pound

Average World Sugar Price, USD per pound

Nickel ores production y exports

The second important resource on the export of which Cuban economy was heavily dependent was nickel ores. During 1971-1988, Cuba used to be the sixth largest world producer of this metal surpassed only by Canada, the Soviet Union, New Caledonia, Australia and Indonesia. Throughout the examined period, Cuba annually produced on average 36 thousand metric tons of nickel and was responsible for 4.9% of world nickel production. Also, analysing the graphs, it is remarkable that there was a drastic difference between the market and planned economies in terms of nickel production. Both the USSR and especially Cuba demonstrated far less fluctuations in terms of both annual production and share of total production figures compared to other examined economies. For instance, the Cuban share of world nickel production never dropped below 4% or surpassed 5.6%, while the Canadian one was between 13.9% and 41.8% during the analysed period (see figures 1 and 4). Therefore, the trend within the Cuban nickel industry that is the constant and stable increase in production resembles the one within the Cuban sugar industry. So, despite the Cuban leaders’ rhetoric about the need of diversification and economic transformations, the dependence on production of both sugar and nickel did not decrease.

Thumbnail

Figure 4

Top World Producers of Nickel (1971-1988), thousand metric tons

Top World Producers of Nickel (1971-1988), thousand metric tons

As for the Cuban exports, like in the sugar case, it was the Soviet Union that became the largest importer of the Cuban nickel and cobalt ores in the 1980s. The USSR alone accounted for more exports of Cuban nickel and cobalt than all other countries in the world both Socialist and capitalist. In addition, it is remarkable that purchases of Cuban cobalt and nickel by the Soviet Union only increased over time, even despite serious economic problems faced by the Soviet leaders after the fall in oil prices in 1985. Thus, throughout the 1980-s the total share of Socialist countries including the USSR in Cuban nickel-cobalt export exceeded 65% with the Soviet Union being solely responsible for a half of total Cuban export of nickel and cobalt (see table 8). Moreover, the Cuban nickel production and exports seem to be only slightly affected by world nickel price changes primary due to the fact that the USSR and other Comecon states were ready to provide stable demand for the Cuban goods (see figure 5). Finally, considering the fact that the USSR itself was the second largest producer of nickel, it is doubtable that the Soviet economy really needed all the imported Cuban nickel.

Table 8

Exports of Nickel-Cobalt Products, tons

Exports of Nickel-Cobalt Products, tons

| 1981 | 39 706 | 19 453 | 49.78 | 6 488 | 16.6 | 13 135 | 33.62 |

| 1982 | 38 005 | 18 093 | 47.61 | 6 703 | 17.64 | 13 209 | 34.75 |

| 1983 | 37 807 | 19 193 | 50.77 | 6 135 | 16.23 | 12 479 | 33.00 |

| 1984 | 36 658 | 18 205 | 49.66 | 7 167 | 19.55 | 11 286 | 30.79 |

| 1985 | 33 376 | 20 709 | 62.05 | 6 450 | 19.32 | 6 216 | 18.62 |

| 1986 | 34 913 | 20 501 | 58.72 | 5 722 | 16.39 | 8 690 | 24.89 |

Thumbnail

Figure 5

Average Nickel Prices, USD per metric ton

Average Nickel Prices, USD per metric ton

Economic implications of trade model realization

For three decades of such unequal cooperation with the USSR and for two decades of membership in the Comecon, the economic model of Cuba did not undergo fundamental changes. The fact is that the country’s leaders did not increase the competitiveness of the Cuban economy. The Cuban leaders failed to overcome Cuban dependence on sugar and nickel exports, did not manage to find a new place for the state in the international division of labor, which eventually led to the country plunging into a severe economic crisis with the elimination of Comecon and the fall of the Soviet Union. Left without convenient trading partners that were ready not only to supply the regime with all the necessary resources to implement all sorts of programs to build socialism, but also to pay generously for Cuban sugar and nickel ores, the Cuban leaders were forced to give up a number of their principles, forget about the pride of the fighters against imperialism and begin to intensify cooperation with Western partners.

Even against the background of other Latin American countries, Cuba’s economic success looks modest. The Cuban gdp per capita in 2011 US dollars for all the years of such profitable cooperation with the USSR did not even exceed 6 000 dollars. Unlike Venezuela, Cuba cannot boast of having the richest oil reserves, does not possess the great human resources of Brazil, has never claimed the status of the most economically developed country like Argentina, is not located on the most important world trade artery like Panama. Still, even a comparison with Pinochet’s Chile (1973-1990) allows us to understand what lies behind the "sustainable economic growth" of Cuba. In fact, throughout the reign of Fidel Castro, Cuba remained an ordinary developing economy of Latin America and the Caribbean. Its only distinctive trait was having a generous older brother, as well as his satellites who were willing to pay for Cuban loyalty. Actually, after the Castro regime coming to power and the beginning of the island’s integration with the Socialist bloc, Cuba that used to be comparable to Brazil, Mexico or Panama in terms of gdp per capita (1946-1959) was surpassed by all the above-mentioned states with the gap only increasing over time (see figures 6 and 7).

Thumbnail

Figure 6

GDP Per Capita of Selected Latin American Countries (1946-1991), 2011 USD

GDP Per Capita of Selected Latin American Countries (1946-1991), 2011 USD

Thumbnail

Figure 7

Cuba’s GDP Growth (1959-1991) (percentage)

Cuba’s GDP Growth (1959-1991) (percentage)

Soviet vs American Pattern of Cooperation

Such a pattern of trade with the Soviet Union may resemble the model of economic interaction between Cuba and the USA before 1959. Even before the revolution of 1959, Cuban economy was heavily dependent on export of sugar and nickel ores. Until 1959 it was the USA that was the key Cuban trade partner responsible for buying its key export goods as well as the leading investor in the Cuban economy in terms of foreign direct investment (Heidingsfield, 1952). Also, it is the revising quotas for the Cuban sugar import that is often considered to be one of the Cuban revolution drivers (Dye and Sicotte, 2004). As for the political dimension, it was the US victory in the Spanish-American War (1898) that resulted in the creation of a formally independent Cuban state. Afterwards, the Platt Amendment (1903) secured the US status of a senior partner towards Cuba that had a right to directly interfere in the interior affairs of the island (Platt Amendment, 1903). So, it is fair to conclude that the Cuban foreign policy used to be virtually directed by Washington to far more extent than it was by Moscow after the Castro regime coming to power. One of the best illustration of such a practice is the fact that Cuba immediately entered World War II after the axis attack on Pearl Harbor.

-

Heidingsfield, 1952Cuba: A sugar economyCurrent History, 1952

-

Dye and Sicotte, 2004The U.S. Sugar Program and the Cuban RevolutionThe Journal of Economic History, 2004

-

Platt Amendment (1903)Treaty between the United States and the Republic of Cuba embodying the provisions defining their future relations as contained in the Act of Congress, 1903

-

Platt Amendment, 1903Treaty between the United States and the Republic of Cuba embodying the provisions defining their future relations as contained in the Act of Congress, 1903

Anyway, such a model of unequal cooperation did not entail the creation of artificial conditions for the Cuban economic development. The USA did not import as much sugar or nickel the Cuban economy was ready to export, did not hedge the Cuban risks associated with the world sugar or nickel prices volatility, did not apply any preferential price models, refrained from direct economic assistance and donations to the Cuban regime. Actually, the trade between the two states was usually based on quotas systems that used to discriminate against the Cuban producers and limit their access to the US market (Dye and Sicotte, 2004). Moreover, Washington never provided Cuba with a net of partners that were ready to assist the island’s regime either following the principle of Socialist solidarity or being forced to do so by Moscow like in the case of Comecon states.

-

Dye and Sicotte, 2004The U.S. Sugar Program and the Cuban RevolutionThe Journal of Economic History, 2004

In fact, Cuba entered the second half of the 20th century as one of the Latin American economies with a great potential that used to be ahead of Brazil and comparable to Panama and Mexico in terms of gdp per capita. But with the conversion to a Socialist state and the beginning of the integration with the Socialist bloc amid US embargo, Cuba immediately started to fall behind other prominent economies of the region (Maddison Project Database, version 2020., Bolt & Zanden, 2020).

-

Maddison Project Database, version 2020., Bolt & Zanden, 2020Maddison style estimates of the evolution of the world economy. A new 2020 update, 2020

Eventually, the implementation of such a pattern of trade and other forms of economic cooperation between the island and other Socialist states not only perverted the Cuban regime enabling the country leaders to take advantage of the artificial exceptional trade conditions but also caused serious discords within the Socialist camp. It is remarkable that as Yordanov (2021) stated Cuban leaders interpreted the existence of preferential prices system as well as assistance programs as an expression of international solidarity (a duty of other Socialist leaders to assist their ideological brothers), while Socialist states’ planners treated such practices as direct economic aid. In the end, considering the Castro regime reluctance to switch the convenient pattern of economic development and reduce the economy’s dependence on sugar exports, it is not surprising that "Cuba’s status of a 'true Mecca for all Latin America' in early 1960 was replaced by the ebb and flow of economic integration of the 1970s and the failed reforms on both sides of the Atlantic in the second half of the 1980s, which presented constant sources of economic tensions between Cuba and the Soviet bloc" (Yordanov, 2021).

-

Yordanov (2021)Bittersweet solidarity: Cuba, Sugar and the Soviet blocRevista de Historia de América, 2021

-

Yordanov, 2021Bittersweet solidarity: Cuba, Sugar and the Soviet blocRevista de Historia de América, 2021

Finally, with the dissolution of the Comecon and the demise of the Soviet Union the Cuban leaders were forced to betray their own principles and commitments to the Communist ideas, had to realize fundamental reforms, open the economy for Capitalist states citizens and seek normalization of the bilateral relations with the USA. All the hardships of such a painful transit to a more market-base and competitive model of sugar and nickel production and trade could have been dodged if it had not been for the three decades of the corrupting cooperation with the USSR.

Alternative way

One may claim that the Cuban economy destiny is not special with Cuba being just an ordinary Latin American economy with undiversified export and strong dependence on a particular resource sale on the world market (considering the USSR and Comecon states factor to be a secondary one). For instance, the Cuban economic model may seem to resemble the ones of Venezuela and Chile since both these states have rich supplies of one resource: Venezuela is one of the key word exporters of oil, while Chile is responsible for a lion’s share of copper exports. It is remarkable that oil and copper prices are among the most volatile in the world, so the economies of Venezuela and Chile must have been affected by exterior shocks at least not less than Cuba (Gaidar, 2020). All the three states used to have comparable export share (percentage of gdp). Moreover, it is noteworthy that the Chilean one has almost doubled under authoritarian Pinochet’s rule (1974-1990): in 1974 it was 19.5%, while in 1990 the share reached 32.5%. Still even against the background of Chile and Venezuela Cuba looks exceptional in terms of its export share dynamics. The fact is that almost until the Comecon dissolution and the collapse of the USSR in 1991, the Cuban export share remained the same with only minor changes: it never fell below 30% until 1990, which is another illustration of the favourable artificial exterior trade conditions secured by the cooperation with the Soviet Union (see figure 8). It is remarkable that the total trade turnover with Socialist states as well as with Comecon states increased during 1970-1982 but it happened amid plummeting exports to developed economies (from 21.4% in 1970 to 9.4% in 1982) (see table 9). So, it explains why the total Cuban export share (percentage of gdp) remained almost the same. The rising trade volume was accompanied by the proportionate gdp growth, while major changes affected only the net of importers and exporters.

-

Gaidar, 2020The Death of the Empire. Lessons for Modern Russia, 2020

Thumbnail

Figure 8

Export Share of Cuba, Chile and Venezuela, Percentage of Gross Domestic Product, 1970-2000

Export Share of Cuba, Chile and Venezuela, Percentage of Gross Domestic Product, 1970-2000

Table 9

Foreign Trade of Cuba by Country Groups (pergentage)

Foreign Trade of Cuba by Country Groups (pergentage)

| Socialist countries | 71.8 | 74.0 | 69.9 | 59.5 | 67.8 | 51.5 | 86.3 | 83.8 | 88.5 |

|

|

63.8 | 64.7 | 63.0 | 56.0 | 64.1 | 48.2 | 81.5 | 78.3 | 84.3 |

| Developed capitalist countries | 25.2 | 21.4 | 28.2 | 33.9 | 25.7 | 41.7 | 9.8 | 9.4 | 10.1 |

| Developing countries | 3.0 | 4.6 | 1.9 | 6.6 | 6.5 | 6.8 | 3.9 | 6.8 | 1.4 |

However, both Chile and Venezuela demonstrated rather stable economic growth rate throughout all the three examined decades. In case of Venezuela, it was relatively low, while in case of Chile, the indicators were the record ones for the Latin American region. Still, none of the economies experienced such a hard-economic crisis Cuba had when its average gdp growth rate turned out to be negative for the whole decade (1991-2000) (see figure 9; table 10). It can be partly explained by the fact that Chile and Venezuela had to adjust their economies to the world market conditions, open competition and did not have any senior partner and their minions who would be ready to provide subsidies and secure stable but artificial demand for the key elements of the state’s exports. Still, there is another difference especially between the economic policy of Castro and Pinochet that is the success in terms of economy diversification and trade liberalization.

Thumbnail

Figure 9

GDP Growth of Cuba, Chile and Venezuela, 1961-2000 (percentage)

GDP Growth of Cuba, Chile and Venezuela, 1961-2000 (percentage)

Table 10

Average GDP Growth of Cuba, Chile and Venezuela (1971-2000) (PERCENTAGE)

Average GDP Growth of Cuba, Chile and Venezuela (1971-2000) (PERCENTAGE)

| Cuba | 4.58 | 2.43 | -0.41 |

| Chile | 2.95 | 3.17 | 5.72 |

| Venezuela | 3.91 | 0.76 | 2.68 |

Unlike Cuba, the Pinochet regime successfully diversified the Chilean exports, managed to reduce the state’s dependence on copper exports and significantly liberalized the Chilean economy. For example, until 1975 the share of copper in total Chilean exports never fell below 68% but with Pinochet’s assumption to power its started to drop: even during 1975-1979 it decreased to 54%, afterwards during the 1980-s it further shortened to 45%. What is more, even after the end of Pinochet reign Chile saw the continuation of this trend: in the 1990-s the copper share in Chilean exports was less than 40% (see figure 10). So, the world copper prices and world demand for Chilean copper changes did not have such a strong impact on the Chilean economic performance like in the Cuban scenario. Also, it is fair to add that Chile never depended on one purchaser of copper like Cuba did in the case of sugar and nickel trade with the USSR.

Thumbnail

Figure 10

Share of Copper Exports in Total Chilean Exports 1960-1999 (percentage)

Share of Copper Exports in Total Chilean Exports 1960-1999 (percentage)

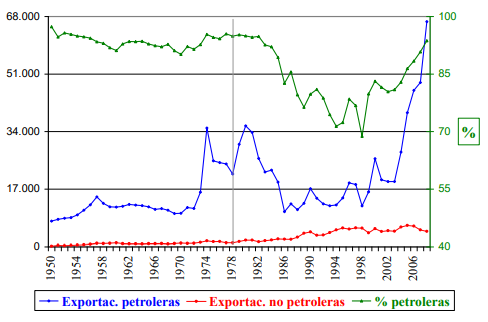

Another remarkable fact is that the late 1970-s and the 1980-s saw the dramatic decrease in the petroleum exports share in Venezuela. Definitely, that was primary caused by the world oil market trends but still unlike Havana Caracas managed to timely react to the exterior challenges primary due to the integration to the global oil market as well as coordination and dialogue within the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries. It is noteworthy that unlike the exports of Cuban sugar and nickel which only grew under the Castro regime the export share of petroleum in Venezuela reduced from more than 95% in 1974 to less than 80% by 1990 (see figure 11). The dependence on oil exports remained significant and almost unprecedented (at least for Latin America), but the economy was able to adjust to the changing market realities. Still, it is fair enough to state that the dramatic oil price drop in the 1980-s was the key reason why the average gdp growth in Venezuela was less than 1% throughout the 1980-s. Anyway, its economy did not collapse as the Cuban one in the early 1990‑s (see figure 9; table 10).

Thumbnail

Figure 11

Venezuela. Petroleum and Non Petroleum Exports, 1950-2008

Venezuela. Petroleum and Non Petroleum Exports, 1950-2008

Conclusions y Discussions

Did anyone benefit from such economic cooperation between Havana and Moscow? The Cuban dictator obtained a great opportunity to boast about the "economic success" of his regime (Castro, 1980, 1984a, 1984b), but in fact, Cuba, for all the years of such profitable partnership with the USSR and the Comecon states, remained a country whose entire economic model was completely focused on the export of resources and agricultural products. The Cuban leaders only took advantage of the favorable conditions created by external factors. Even against the background of other Latin American economies performance, the Cuban one looks modest. Unfortunately, within the framework of the Comecon, Cuba became an economy that was parasitic both on gratuitous assistance from the USSR and on exceptional exterior conditions, namely, the readiness of the other Socialist countries not only to supply the island with the equipment, technologies, and energy resources it needed, but also to show a stable demand for Cuban sugar and nickel. Such an economic policy led to a serious economic crisis in which the country found itself after the dissolution of the Comecon, the fall of the USSR and the disappearance of Socialist partners. As was clearly demonstrated in The Demise of the Soviet Empire and Its Effects on Cuba by Leroy A. Binns (1996), already in 1990, Cuba faced many economic problems: from the growing state budget deficit, to the reduction of the sugar industry, and its leaders were forced to begin implementing large-scale economic reforms to open the Cuban economy to the Western world. As for the Socialist block benefits, the realization of such a pattern of trade accompanied with assistance programs within the Comecon led to serious discords and misunderstanding between the Cuban leaders and other member states representatives (Yordanov, 2021).

-

Castro, 1980Fidel Castro Reads Main Report at PCC Congress, 1980

-

1984aCastro speaks at Cuban National Day Meeting, 1984

-

1984bCastro speech at students Congress, 1984

-

Leroy A. Binns (1996)The Demise of the Soviet Empire and Its Effects on CubaCaribbean Quarterly, 1996

-

Yordanov, 2021Bittersweet solidarity: Cuba, Sugar and the Soviet blocRevista de Historia de América, 2021

Definitely, the Cuban economy was undeveloped and relatively small, Havana’s domestic financial resources were limited, and it was an extremely challenging task for the state’s leaders to secure rapid economic development. Also, it is almost impossible to combine it with a comprehensive social program implemented by the Castro regime (Leogrande & Thomas, 2002). Still, the example of Pinochet’s Chile the economy of which also used to depend on one resource exports shows that an authoritarian regime can secure favorable conditions for record economic growth rates, liberalize and diversify an economy so that it claims the status of one of the most successful ones in the whole region. Even the comparison to Venezuela shows that an economy that totally depends on the exports of one particular good can mitigate the shocks on the resource market by economic integration, cooperation, liberalization as well as stabilizing measures (e.g. national stabilizing funds) (Gaidar, 2020). The Cuban leaders got used to the artificial economic reality their state existed in for three decades and were not ready to timely react to the global shifts. That is why in the conditions of the free market sugar price the island’s economy was plunged into a serious crisis, and its leaders betrayed the proclaimed dogmas and ideals for the sake of survival (market economic reforms and opening for trade with Capitalist states).

-

Leogrande & Thomas, 2002Cuba’s Quest for Economic IndependenceJournal of Latin American Studies, 2002

-

Gaidar, 2020The Death of the Empire. Lessons for Modern Russia, 2020

This research is a case study, so its results are limited to the interaction between the USSR and Cuba and cannot be easily used to make conclusions about the cooperation between the Soviet Union and other states. Still, it presents a great field for further investigation. The outcome of future studies may help to shed light on the economic decay of the Soviet Union and the Socialist bloc, expand on the topic of the global economic confrontation between the USA and the USSR, and to be used to further compare the US and USSR patterns of trade and economic assistance during the Cold War.

Referencias

- Allison, R. (1961). Cuba’s Seizures of American Business. American Bar Association Journal, 47(1), 48-51. Links

- Andrew, G. (2013). Fidel Castro visits the U.S., April 15, 1959. Retrived from https://www.politico.com/story/2013/04/this-day-in-politics-april-15-1959-090037 Links

- Bekarevich, A. D. and Kukharev, N. M. (1990). Soviet Union-Cuba: Economic cooperation (70-80s). Moscow: Nauka. Links

- Binns, L. A. (1996). The Demise of the Soviet Empire and Its Effects on Cuba. Caribbean Quarterly, 42(1), 41-54. DOI: 10.1080/00086495.1996.11672082 Links

- Blasier, C. (2002). Soviet Impacts on Latin America. Russian History, 29(2/4), 481-497. Links

- Burueau of Mines (1972). Bureau of Mines Minerals Yearbook (1932-1993) U.S. Geological Survey (vol. 3). Washington, D. C.: United States Government Printing Office. Links

- Castro, F. (1980). Fidel Castro Reads Main Report at PCC Congress. F1171620. Castro Speech Data Base. Havana. Retrived from http://lanic.utexas.edu/project/castro/db/1980/19801217.html Links

- Castro, F. (1984a). Castro speaks at Cuban National Day Meeting. LD272240. Moscow TASS. Retrived from http://lanic.utexas.edu/project/castro/db/1984/19840727.html Links

- Castro, F. (1984b). Castro speech at students Congress. LD090928. Castro Speech Data Base. Moscow. Retrived from http://lanic.utexas.edu/project/castro/db/1984/19841209-1.html Links

- Cuba. Member of Comecon (1984). Council for Mutual Economic Assistance [Comecon] Secretariat. Moscow: Consejo de Ayuda Mutua Económica. Links

- Divercitytimes (2022). Nickel Price Annual and Monthly [years 1971-1988]. Retrived from https://divercitytimes.com/commodity/nickel.php Links

- Dye, A. and Sicotte, R. (2004). The U.S. Sugar Program and the Cuban Revolution. The Journal of Economic History, 64(3), 673-704. DOI: 10.1017/S0022050704002931 Links

- Eckstein, S. (1980). Capitalist constraints on Cuban socialist development. Comparative Politics, 12(3), 253. DOI: 10.2307/421926 Links

- Gaidar, E. T. (2020). The Death of the Empire. Lessons for Modern Russia. Moscow: AST. Links

- Gregorio, J. de. (2004). Economic growth in Chile: Evidence, sources and prospects [Working Papers Central Bank of Chile]. Central Bank of Chile. Links

- Heidingsfield, M. S. (1952). Cuba: A sugar economy. Current History, 22(127), 150-155. DOI: 10.1525/curh.1952.22.127.150 Links

- Hoff, F. L. and Lawrence, M. (1985). Implications of World Sugar Markets, Policies, and Production Costs for U.S. Sugar. Research Service. Agricultural Economic Report (543). United States: Department of Agriculture Economic. Links

- Lehmann, D. (1979). The Cuban economy in 1978. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 3(3), 319-326. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.cje.a035427 Links

- Leogrande, W. M. and Thomas, J. M. (2002). Cuba’s Quest for Economic Independence. Journal of Latin American Studies, 34(2), 325-363. doi:: 10.1017/S0022216X02006399 Links

- Macrotrends (1970-2020). Retrived from https://www.macrotrends.net/ Links

- Maddison Project Database, version 2020. Bolt, J. and Van Zanden, J. L. (2020). Maddison style estimates of the evolution of the world economy. A new 2020 update. Retrived from https://www.rug.nl/ggdc/historicaldevelopment/maddison/publications/wp15.pdf Links

- Martynov, B. F. (2019). History of international relations of Latin America and the Caribbean (19th-early 21st Century). Moscow. Links

- Palacios, L. and Layrisse de Niculesco, I. (2011). Crecimiento en Venezuela. Una Reconsideracion de la Maldicion Petrolera. Documento de Trabajo, Escuela de Economía. Links

- Perez-Lopez, J. (1988). Cuban-Soviet Sugar Trade: Price and Subsidy Issues. Bulletin of Latin American Research, 7(1), 137-145. Links

- Platt Amendment (1903). Treaty between the United States and the Republic of Cuba embodying the provisions defining their future relations as contained in the Act of Congress. National Archives Building, Washington, DC. Retrived from https://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=true&doc=55 Links

- Pollitt, B. (2004). The Rise and Fall of the Cuban Sugar Economy. Journal of Latin American Studies, 36(2), 319-348. Retrived from https://www.jstor.org/stable/3875618 Links

- Pollitt, B. and Hagelberg, G. (1994). The Cuban Sugar Economy in the Soviet Era and After. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 18(6), 547-569. Retrived from https://www.jstor.org/stable/24231831 Links

- Stroganov, A. I. (2017). Latin America: Pages of 20th Century History. Moscow: LIBROCOM. Links

- Valenta, J. (1981). The Soviet-Cuban Alliance in Africa and the Caribbean. The World Today, 37(2), 45-53. Retrived from https://www.jstor.org/stable/40395260 Links

- Valetov, T. (2015). Non-Ferrous Metals of the USSR: Their Production and Trade in 1917-1966. ISTORIYA, 6(8), 41. doi: 10.18254/S0001265-0-1 Links

- Walters, R. S. (1966). Soviet Economic Aid to Cuba: 1959-1964. Royal Institute of International Affairs, 42(1), 74-86. doi: 10.2307/2612437 Links

- Wiesel, I. (1968). Cuban Economy and the Revolution. Acta Oeconomica, 3(2), 203-220. Retrived from https://www.jstor.org/stable/40727812 Links

- World Bank (1972-1900a). Infant Mortality Rate for Cuba. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Links

- World Bank (1972-1900b). Life Expectancy at Birth, Total for Cuba. Retrived from https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/SPDYNLE00INCUB Links

- Yordanov, R. (2021). Bittersweet solidarity: Cuba, sugar and the Soviet bloc. Revista de Historia de América, 161, 215-240. doi: 10.35424/rha.161.2021.855 Links

Source: Burueau of Mines (1932-1993, vol. 3, years 1971-1988).

Source: Burueau of Mines (1932-1993, vol. 3, years 1971-1988). Source: Bekarevich and Kukharev (1990).

Source: Bekarevich and Kukharev (1990). Source: Macrotrends (1970-2020, Sugar Prices-37 Year Historical Chart, years 1971-1988).

Source: Macrotrends (1970-2020, Sugar Prices-37 Year Historical Chart, years 1971-1988). Source: Burueau of Mines (1932-1993, vol. 3, years 1971-1988).

Source: Burueau of Mines (1932-1993, vol. 3, years 1971-1988). Source: Divercitytimes (2022, Nickel Price Annualy and Monthly, years 1971-1988).

Source: Divercitytimes (2022, Nickel Price Annualy and Monthly, years 1971-1988). Source: Maddison Project Database, version 2020., Bolt and Zanden (2020).

Source: Maddison Project Database, version 2020., Bolt and Zanden (2020). Source: Maddison Project Database, version 2020., Bolt and Zanden (2020).

Source: Maddison Project Database, version 2020., Bolt and Zanden (2020). Source: Macrotrends (1970-2020, Cuba, Chile, Venezuela Exports).

Source: Macrotrends (1970-2020, Cuba, Chile, Venezuela Exports). Source: Maddison Project Database, version 2020., Bolt and Zanden (2020).

Source: Maddison Project Database, version 2020., Bolt and Zanden (2020). Source: Gregorio (2004).

Source: Gregorio (2004). Source: Palacios and Layrisse de Niculesco (2011).

Source: Palacios and Layrisse de Niculesco (2011).