Background

William Hunter first described SVCS in 17571. Malignant lesions cause the most; however, 40% are related to benign causes like mediastinal fibrosis, postradiation or central venous line placement sequelae as well as pacemakers1,2. Nineteen thousand cases of SVCS occur each year in the United States, with an increasing frequency related to endovascular procedures3.

Treatment of SVCS can be open or endovascular. Endovascular provides rapid relief of symptoms and clinical improvement regardless of the etiology. Sfyroeras performed a meta-analysis between open versus endovascular surgery for benign SVCS (13 studies included). Nine reported endovascular treatment outcomes, both procedures with good results and improvement of symptoms4.

Haddad performed a retrospective study on stent selection with 47 benign SVCS patients and compared covered versus uncovered stents after balloon angioplasty, using closed cell uncovered stents. He reported 97.3% of symptoms regression with uncovered stents with poor results as for covered stents (29.4%)5. There is no consensus if anticoagulation on a long-term basis is required; nonetheless, anticoagulation is recommended after the placement of an iliocaval venous stent, with no information regarding open surgery6. No guidelines or algorithms are available to guide the care and follow-up after SVC stenting. Patients must be monitored for clinical symptoms; and venous duplex ultrasound or CT venograms should be performed if symptoms suggest reocclusion of the superior vena cava7.

Clinical case

The patient agreed to allow the authors to publish their case details and images. A 60 years old female with a iatrogenic SVCS due to in-stent thrombosis and, associated with a left brachiocephalic stent decoupling. Two previous left brachiocephalic stents were placed proximal to the right brachiocephalic vein, occluding the superior cava vein after thrombosing (Table 1). The patient was treated endovascularly without improvement by two different physicians. SVCS was suspected by US Doppler because of absent retrograde cardiac pulsatility and phasicity in the jugular and the distal subclavian veins, bilaterally.

Table 1 Medical history and timeline

| Medical history | Female | 60 year | DM2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atrial fibrillation | |||

| 2 years | Infiltrating intraductal right breast cancer | ||

| Left subclavian port catheter placement 3 year | |||

| 32 radiotherapy and 6 chemotherapy sessions | |||

| Primary right ovarian cancer | |||

| Six chemotherapy sessions | |||

| 1 year | Port removal | ||

| January 2020 | Left subclavian vein thromosis | ||

| Left subclavian vein stenting by left axillary approach by coupling two 10×100 mm absolute pro stents and a superior vena cava filter | |||

| July 2020 | Facial plethora, facial venous congestion, significant collateral circulation, and perioral cyanosis dyspnea requiring non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NIMV) during night sleep | ||

| August 2020 | Phlebography by a right femoral vein access with filter patency with an unsuccessful attempt for filter removal symptoms did not resolve and were complicated by a subcapsular hematoma (240 cc) associated with intraoperative anticoagulation | ||

| September 2020 | US Doppler examination we suspected SVCS, probably secondary to filter thrombosis: | ||

| Absent retrograde pulsatility, and absent phasicity in yugular and distal subclavian, bilaterally | |||

| Third endovascular procedure. Described in nivel techinique | |||

Technique

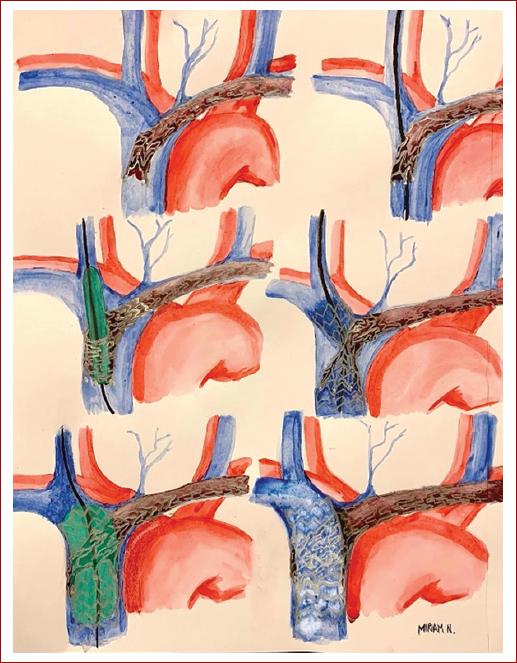

Right jugular approach (Step I) crossing the struts of the left brachiocephalic stent with a hydrophilic guidewire (Step II) through the occluded superior vena cava to the inferior vena cava (Table 2). Pre-dilation is required (Step III) due to the crossing of the struts of the stent, allowing the structural modification of the struts (crushing) and the placement of a Zilver vena stent 60 × 14 × 60 mm (Step IV), always observing a residual constriction just at the site of the crossing cells, which we call it an hourglass image. Finally post-dilation was performed (Step V) with control phlebography (Step VI) (Fig. 1). In this case, during post-dilation step (V), the guidewire was pulled by mistake and lost without being able to cannulate the same strut again, so the procedure was repeated once more, through another cell, with the same pre-dilatation progression, and the same stent. Final phlebography showed partial in-stent thrombosis but abundant collateral circulation. At the end of the procedure, the patient experienced the disappearance of facial congestion and relief of the dyspnea as a sign of a marked increase in venous return, immediately after stent release, despite in-stent thrombosis.

Table 2 Transtenting

| Step I | Right jugular access: patent right brachiocephalic trunk |

|---|---|

| Thrombosed left brachiocephalic stent occluding SVC | |

| Step II | 0.035 hydrophilic guidewire crossing struts of the stent |

| Step III | Pre-dilation through the cells from 8 mm to 16 mm ballons |

| Step VI | Zilver vena stent placement (60×14×60 mm). Residual stenosis just at the site of crossing cells (Hourglass image) |

| Step V | Post-dilation from 8 mm to 16 mm ballons |

| Step VI | Final result |

6 h procedure. Low doses of unfractionated heparin were used because of history of subcapsular hematoma. Outpatient clinic procedure.

Discussion

A similar technique has been previously documented in the mispositioning of coronary stents at the bifurcation8 also known as Crush and Culotte, but not in large venous trunks. In addition, Krasemann, in an in vitro study, demonstrated that dilation and over-dilation are possible through open cells with balloons of greater luminal diameter9.

In our case, SVCS is secondary to a contralateral stent misposition in the left toward the right brachiocephalic vein, associated to in-stent thrombosis related to stent decoupling; that is why we decided to perform this innovative technique.

Although we observed relief of the symptoms, we cannot consider it a technical success due to the loss of the guidewire and the need to repeat the procedure through another cell (strut), resulting in thrombosis. Nonetheless, we did observe immediate clinical improvement after the disappearance of respiratory distress, immediate reduction of facial swelling, and stopping dependence on continuous positive airway pressure during nighttime rest.

We associated thrombosis with excessive surgical time (360 min), the need to repeat the procedure a second time, endothelial injury secondary to a port catheter, and the double chemotherapy administration for breast cancer and ovarian cancer, radiotherapy, and poor anticoagulation doses due to the 7 days evolution of a subcapsular renal hematoma. We did not decide to use suction devices resolving in-stent thrombosis because they were not available at that time, and we decided not to perform thrombolysis due to the recent history of left renal intracapsular hemorrhage; in addition, to the exhaustion of financial resources by the patient. Long-term oral treatment with Rivaroxaban and Ticagrelor 90 mg was indicated due to the personal history.

Conclusion

We will see an increase in the number of cases of iatrogenic SVCS. In our experience, crossing a guidewire through the struts of a previously placed stent to release a self-expanding stent and post-dilation of the cells is possible, with high technical and clinical success rates once the technique is improved, but still, proper studies are needed. Endovascular treatment is associated with few complications and rapid clinical improvement. And, it is a safe and effective method, with a short hospital stay even in an outpatient context, so we consider that it should always be the first option in thoracic vessels.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)