1. Introduction

Exogenous forces may disrupt the normal operation of any type of business, and there is a continuous occurrence of crises and disasters of different nature that respond to the risks that make organizations vulnerable. According to the World Economic Forum (2019), major global risks include natural disasters, and their impact and likelihood of occurrence are high. The risks-trends interconnection map illustrates the interrelation of climate change and natural disasters with other variables associated primarily with environmental risks (World Economic Forum, 2019, 4-6) that require study from a leadership perspective.

Within this context, the following research aims at answering the following question: How do business leaders develop resilience in their organizations in a catastrophic scenario, particularly in the face of an earthquake? For instance, earthquakes are not uncommon, and in recent Mexican history, two significant events-one in 1985 and another in 2017-impacted Mexico City and affected thousands of businesses and millions of citizens. As more earthquakes are anticipated, the preparation of business leaders and their organizations for this kind of event must be proactively supported in the future. By conducting a participatory study to understand the perspective of 12 business leaders, the focus of the present study is on the effects of the September 19, 2017 (19S) earthquake in Mexico City, in order to contribute to the theory and practice of leadership regarding the development of organizational resilience in a catastrophic environment.

The research’s purpose is to enhance earthquake preparedness, which could potentially be also applicable to other types of disasters given the conceptual contribution to the disaster resilience theory.

Through an iterative process of observing, discussing, analyzing, interpreting and comparing the empirical research findings with the literature, it is possible to contribute to a better understanding of organizational resilience through mechanisms that reinforce leadership in catastrophic environments. This research contributes to organizational resilience and, ultimately, to industrial sustainability as described in the United Nations’ (2015) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Empirically, change expected resulting from the study is linked to Serrat’s (2017) sustainable livelihoods framework, in which human, natural, financial, physical and social capital are vital assets that interact with policies, institutions, livelihood outcomes and strategies applied to organizational sustainability.

This research is considered transdisciplinary, as it crosses academic boundaries and involves practitioners dedicated to knowledge production (Wickson et al., 2006). To address this complex phenomenon, an interaction of fields of knowledge is needed, as well as alternative sources of information and a collection of methods, all required in transdisciplinary research.

2. Literature Review

In order to answer the research question mentioned earlier, the main fields of reference reviewed included disaster resilience and leadership in relation to crisis management. In this context, crises are defined as events and as processes that help understand and activate the necessary mechanisms to respond to major disturbances (Williams et al., 2017).

Disaster Resilience

Countless methods of studying disasters, crisis management and recovery exist. In recent years, scholars have expressed a growing interest in defining and understanding resilience (Werner, 2005). The literature initially described individual resilience; in parallel, some scholars focused on community resilience (Abramson et al., 2014); and in recent years, the concept was applied to organizations (Lengnick-Hall, et al., 2011).

The resilience construct has been defined in various ways (Abramson et al., 2014; Cox & Perry, 2011; Cutter, 2014; Duchek, 2020; Kenney & Phibbs, 2015). Paton and Johnston’s (2006) definition of resilience-as a socioecological phenomenon related to the adaptive capacity of a society to a changed reality-can be translated into a measure of the capitalization of new possibilities. Possible outcomes include mitigation or risk reduction, adaptation, recovery and learning (Paton & Johnston, 2006). The research participants in this study defined resilience as «recovering from severe damage.»

The resilience construct has been already described theoretically for organizations, and it considers the generation of capabilities as well as the process of transformation enhanced by leaders (Duchek, 2020). Given the previous explanation, Duchek (2020) conceptualized resilience as a «meta-capability» and divided the construct into three successive stages-anticipation, coping and adaptation-preceded by assigning organizational capabilities to each stage.

After conducting a metatheoretical review, Duchek (2020) developed a more robust definition of organizational resilience when compared to previous literature, as the construct is not only focused on the aftermath of a disaster, but also to previous processes and to the adaptative mechanisms that occur simultaneously as the exogenous force unfolds. Duchek’s (2020, 220) definition states that organizational resilience is «an organization’s ability to anticipate potential threats to cope effectively with adverse events and to adapt to changing conditions». Based on a detailed analysis of definitions and models, Duchek (2020) also proposed a framework for understanding and developing organizational resilience. The definition and the framework that Duchek developed served as the major framework of the present study in order to compare the findings and the work of other authors who have also studied the phenomenon.

Different scholars have conducted empirical studies on resilience in countries affected continuously by natural disasters. Nakagawa and Shaw (2004), for instance, underlined the importance of social capital for disaster recovery in two post-earthquake reconstruction cases in Japan and India and contrasted the results. Among Nakagawa and Shaw’s contributions is an emphasis on the post-disaster reconstruction process and the introduction of the concept of trust as a critical component of social capital. Trust can strengthen the bonds required to build social and human capital during the recovery and prevention stages.

In addition, the literature on organizational resilience improvement has provided a clearer path to identify the main organizational resilience attributes, pointing out the importance of situational awareness, management of vulnerabilities, and adaptation (McManus et al., 2008). Furthermore, a group of Australian scholars published a compendium of stories and practices from various disasters in which they applied different frameworks to various crisis types (Paton & Johnston, 2006, 2017). Also, publications from the Asian Development Bank (2016) and the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction of the Sendai Framework (2015), and experts from the Red Cross (Mays et al., 2014; Walton et al., 2016) support the theoretical frameworks with experiential and practical recommendations for disaster environments.

Other authors have studied how disasters relate to the development of community resilience. For example, Cox and Perry (2011) analyzed the interrelationship of place, identity and social capital after a wildfire in Canada. Furthermore, the importance of coordinating collective action and the use of information in dynamic disaster environments is also worth considering. There is an increasing interest in developing tools to measure organizational resilience (Lee et al., 2013). Other approaches to this rather complex topic include considering long- and short-term variables in order to build resilient communities to face hazards sustainably (Cutter, 2014).

Scholars who described the impact of earthquakes also explored the psychosocial effects reflected in the psychology of disaster theory. For example, Cohen (2002) focused on the importance of disaster victims’ access to mental health services, whereas Kalayjian, Kanazi, Aberson, and Feygin (2002) addressed the psychosocial and spiritual impacts of natural disasters through cross-cultural research that addressed post-traumatic stress disorder in two studies, one in California and the other in Turkey. Similarly, Sassón (2004) studied the impact of catastrophes and mental health and described the stages that groups or communities experience after being impacted by a disaster.

Moreover, Abramson et al. (2014) developed a resilience activation framework in which resilience is a construct that derives from individual and collective attributes oriented toward the development of mental health; one of the main components is social capital. Bebbington (1999, 2021) underlined the importance of social capital as well and defined it as «an asset through which people are able to widen their access to resources and other actors.» He also proposed a framework for the capabilities, capitals and aspects that characterize sustainable communities.

The missing component from the literature reviewed on disaster resilience is the reference to the role of leaders in the development of resilience capabilities across the organization or in the continuum considering all of the stages that occur prior to a disaster, during the coping phase, and after the catastrophic event.

Leadership and Organizational Resilience

Leadership interacts with disaster resilience as an agent that responds to the modified circumstances that a crisis presents. The question here is to understand who these leaders are. It is critical to note that most leadership paradigms are leader-centered, but follower-centered perspectives on leadership also exist (Jackson & Parry, 2011). In a disaster environment such as that of the 19S earthquake, such perspectives are relevant, as the leadership role becomes more of a flux than a fixed function or a person. Leadership emerges as a capability rather than a hierarchical position. Fortunately, Jackson and Parry (2018, 9) recently acknowledged the relational nature of leadership and defined it as «an interactive process involving leading and following within a distinctive place to create mutually important identity, purpose and direction.»

Personal leadership has been extensively studied from different perspectives, but literature on leadership in catastrophic environments is still limited. To successfully address a crisis situation, individuals need to act with emotional intelligence (Jin et al., 2010) and exercise their leadership (Solomon, 2011; Wang et al., 2018). Emotional intelligence literature (e.g., Goleman, 2000), is closely related to resilience and the connection between thinking, feeling and deciding (Fenton-O’Creevy et al., 2011) may become crucial in a disaster environment. In addition, under the most challenging circumstances, the ethos of leadership surfaces as it interacts with identity, virtue (Arjoon, 2000), values (Barrett, 2006), self-awareness (Zes & Landis, 2013) and with the sacred space where leadership occurs (Grint, 2010).

It is also necessary to consider interpersonal and group dynamics and conflict (Bolman & Deal, 2008) that necessarily emerge during a crisis. Furthermore, it is important to mention the follower-centered (Meindl, 1995) and distributed leadership theories (Jackson & Parry, 2011).

The interconnection of human resources and management (Ulrich, 1998) provides more elements to connect the business strategy literature with the practice of human resources and the application of conceptual frameworks regarding organizational resilience (Lengnick-Hall et al., 2011).

Collaborative leadership may enhance the connectedness that develops inside and outside organizations that is critical in a discontinuous change environment like a catastrophe. For instance, the field of «neuro-leadership» explores concepts such as relatedness and empathy, stressing the importance of developing strong relationships that can improve thinking and performance in individuals and teams (Rock et al., 2012) applied to teams and organizations in the early stages of a disaster or during its recovery phase. The field of neuro-leadership reinforced the interrelationship of leadership, collaboration, and influence (Lafferty & Alford, 2010); this has implications for organizations that focus their efforts on transformational aspects that can empower strong leaders who are capable of facing any type of crisis.

There is an opportunity to contribute to the literature on resilience by exploring business leaders’ responses to earthquakes and the potential resurgence of organizations affected by an environmental emergency. The contribution to a framework that can provide insight into how to act before, during, and after an environmental crisis is crucial to developing the capacity to survive, recover, transform and grow in disaster environments.

3. Epistemological Approach and Methodology

The epistemological approach taken by the researcher of the present study and the research participants reflected on the nature of the relationship between the knower and the knowable (Lincoln & Guba, 2013), which can be classified in the so-called «participatory worldview paradigm» (Heron & Reason, 1997). In order to include this perspective in the research design, the selected methodology was qualitative and inductive in nature. This methodology was chosen because it supports the development of applied research that can be echoed by the actors to be influenced- who are business leaders-and simultaneously looks both for a theoretical and a pragmatic application of the knowledge generated by the study.

In other words, following the proposal from Eisenhardt et al. (2016) to address grand challenges toward sustainable development through inductive methods, this work is an example of theory building through participatory action research, with an inductive and interpretive approach. In this sense, the methodology was based on the following principle: to reflect and to act, while data was collected in a participatory way (Baum et al., 2006). This perspective allowed a meeting of worldviews «to join with fellow humans in collaborative forms of inquiry» (Heron & Reason, 1997, 275-276) in a relational perspective with an alive environment, while addressing a fundamental and complex topic: disaster resilience.

Methods

The methods to support the research process from the exploratory, ex post facto, qualitative research included semi-structured interviews and focus groups. As the research evolved, these forms were combined to collect and process the information coproduced with the research participants.

Context. The research took place in Mexico City, where the urban population is highly concentrated, and the risks of a catastrophe are higher for this reason. The phenomenon of migration from rural to urban areas is derived, in part, from the idea that quality of life increases with access to services, education, employment and health care that can be found in cities. Urbanization that includes suitable living conditions is also associated with complex sustainability challenges that require immediate attention. Environmental risks are exacerbated in concentrated urban settings such as the area of Mexico City (Sachs, 2015).

Additionally, the context in which the research was developed is related to a previous historical event. In 1985, a devastating earthquake reached a magnitude of 8.1 in Mexico City and caused a profound impact on the population. The damage accounted for approximately two million residents losing their homes and 19 000 inhabitants being killed or severely injured, although the official estimates were not precise. Approximately 50 500 buildings were damaged, and more than 5 500 people went missing (Dynes et al., 1990). In 2017, a series of earthquakes affected 18 000 buildings, causing 47 of them to collapse or sustain severe damage, and 328 people were officially reported to have died («Sismos 1985/2017,…» 2018). The reality is that earthquakes in Mexico City will continue to happen, as geologist Cruz Atienza (2015) has warned. The reason being the location of the country in a place where four tectonic plates converge-the Pacific, the Rivera, the Cocos and the Caribbean (Cruz Atienza, 2015, 7-13)-which is also an active volcanic region.

Data collection. The previously mentioned methods were combined to collect and process the information produced with the research participants. The data collection stage of the research process included three focus groups with an average of four participants, and 12 interviews with volunteer leaders who represented their organizations, discussing their experience as leaders, documenting some of their best practices and co-producing an organizational resilience development model. The open invitation to participate in the study was announced verbally at an alumnus meeting in a business school in Mexico City; the requirements to participate in the study included being in a business affected by the 19S earthquake, and interest in collaborating with this research. Participants did not have to be part of the alumni of the school, and in fact three of them were not former students there but were informed about the study by someone else. From a list of 25 self-selected individuals, 12 confirmed their participation after being contacted by phone and the researcher did not require to recruit more participants since a level of saturation was reached with the 12 participants to contribute to answer the research question.

All the participants signed consent forms and were carefully informed about the anonymity of the process, and the ability to leave the study at any time if they decided to do so. The initial contact was to work in small focus groups to answer a previously designed questionnaire based on the technique of appreciative inquiry (Cooperrider & Whitney, 2005).

The first question, on the use of artifacts as a source of evidence, designed originally to build rapport, considered this possibility. The question made reference to an object to introduce oneself and describe the experience in the 19S earthquake. For example, in one of the focus groups, a participant who evacuated a building that collapsed showed the group a pen that she held in her hands along with her cellular phone at the moment of the earthquake; someone else showed a piece of jewelry that was a gift from one of the victims; and a third participant described the blouse she was wearing the day of the earthquake, which she keeps as a token of that event. These artifacts references people’s their associations with the physical environments in which the event the research addressed took place and within the organizational space that contains the culture and meaning of the symbolic objects used on gathering the data of the study (Schein, 2010).

Since the focus groups and the semi-structured individual interviews were directly conducted by the same researcher, in an environment of trust and confidentiality, the individual interview provided an opportunity to go deeper into the discussion about the personal experience of each participant.

The series of focus groups and interviews helped to reflect on the participants’ experience, with the aim of elaborating on an existing theory and compare a series of organizational resilience processes reported in the literature to increase readiness to face future occurrences of this kind. Before, as mentioned, the questions that served as a guide to interview the participants were designed on the principles of appreciative inquiry to «search for the best in people, their organizations and the world around them» (Cooperrider & Whitney, 2005, 8). Therefore, the questions were focused on understanding the best aspects of what happened before, during and after the earthquake and how some leaders were able to develop resilience in their organizations while in a process of adaptation and recovery of a disastrous event.

Data processing and analysis. The recordings from individuals who participated in the focus groups and semi-structured interviews were transcribed and coded by hand and then compared to an NVivo (software) query to extract information and observe similarities. The conversations analysis complied with the COREQ criteria for reporting qualitative research (Tong et al., 2007). Because the interviews and focus groups were conducted in Spanish, the transcriptions and the coding were done in the original recorded language. The generated information was continuously compared with the literature review to understand the emergence of empirical categories through the evidence, which were classified as second-order themes.

Data collected through the interviews and focus groups were compared with the researcher’s observation notes and information published in the social and printed media-such as books and newspapers-in order to have the objective, complete and correct contextual information as a reference for the observations and stories communicated by the participants.

4. Findings

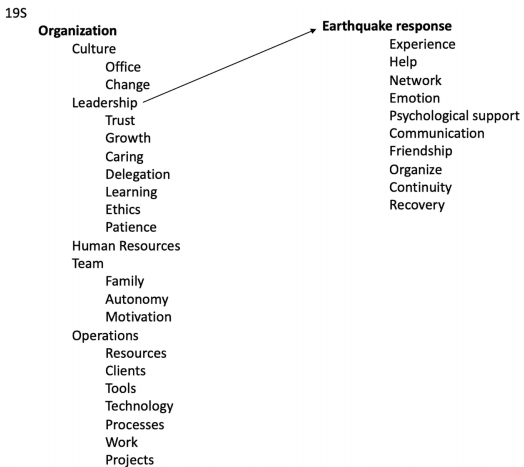

In the process of analyzing the qualitative data obtained as mentioned, initially all the transcriptions were categorized in nodes, resulting in 274 nodes, classified into first-order codes (see Appendix A) by their prevalence and relevance to the research participants, and then into second-order codes (Gioia et al., 2013) while being compared with the literature, and mapped into the organizational resilience framework by stages in relation to the catastrophic event (see Figure 1, p. 55).

The two main categories in the data set correspond to the organization and the response to the 19S earthquake. This segmentation has a relevant meaning in so far as the participants explained the condition of their organization before, during and after the earthquake. With this in mind, it was possible to identify elements that were integrated from the organization into the earthquake response, such as culture and more specifically leadership characteristics that influenced the response of the organization to such a critical event, as the arrow indicates in the diagram (see Appendix A). The researcher missed the possibility to code the respondents’ emotions, as in the data collection process there were long silences, tears, sighs, expressions of frustration, anger and joy, followed by relevant reflections, but at present there are no data analysis methods techniques capable of gathering this type of information.

To answer the research question about how business leaders develop resilience in their organizations in a catastrophic scenario, particularly in the face of earthquakes, the Duchek (2020) framework used as the anchor of this exploratory research has not been applied empirically before or discussed further. As Fisher and Aguinis (2017) asserted, in theory elaboration, it is possible to contrast, specify or structure existing theories in the process of accounting for or explaining empirical observations. Therefore, in an inductive process there was an iterative comparison of an existing framework on organizational resilience (Duchek, 2020) with definitions and interpretations from the research participants.

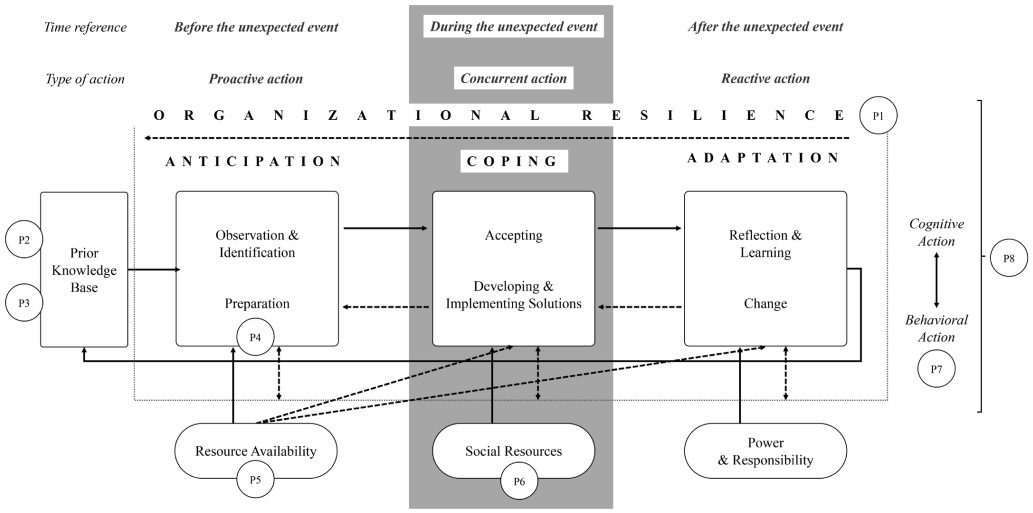

After comparing Duchek’s framework (Figure 1, p. 55) with the reflections collected throughout the research and with the research participants, there were eight propositions that emerged from the data. The propositions that can be sorted by the successive stages Duchek has presented in her work: anticipation, coping and adaptation.

Proposition 1 (P1). Resilience is a nonlinear continuum that starts with the generation of awareness of potential organizational risks-supported by data collected through risk assessment and experience-activated in organizations with the necessary action protocols, business continuity efforts, financial provisions, crisis communication strategies, human resources, technology and infrastructure.

Proposition 2 (P2). The organizational culture is a disaster-preparedness mechanism that is supported by leadership exercised in alignment with the universal human rights and in adherence to ethical principles.

Throughout the different data collection phases, corruption was mentioned in all cases as an obstacle to developing resilience. The corruption that the research participants referred to included governmental entities, but also businesspeople and the civil society in general, specifically manifesting in acts such as sabotage, lack of adherence to the law, and a lack of law enforcement by governmental institutions and actors.

Also, as Duchek (2020, 237) asserted, among the social sources of resilience, there is a «call for open, trustful and learning-oriented organizational culture». Duchek even included culture as a coping mechanism in her framework; throughout the empirical research, culture was evident as a protective factor that precedes and influences the three stages of resilience development, which are anticipation, coping and adaptation.

The concept of culture in the present research was extended to traits of Mexico, described as a risk-averse but supportive culture. Solidarity has been a cultural strength that has allowed the formation and consolidation of civil society in Mexico since 1985, but it may also represent threats given the dysfunctional performance of governmental institutions and may cause more harm than good without coordination with the central, elected authorities.

Proposition 3 (P3). Employee response to environmental events in organizations is activated by emergent leaders (Mucharraz, 2020) in the case of a crisis and is tested in minor crises. Emergent leadership is related to horizontal power distribution and shared responsibility, collaborative leadership, diffused power and holographic rather than hierarchical structures (Lengnick-Hall et al., 2011). After the 19S earthquake, leadership was not displayed as supported by a hierarchy, a title, an office size or a salary, but was distributed and transformed into solidarity in the coping stage, so it was necessary to explore the role of distributed leadership during the research while relating insights derived from followership theories.

Proposition 4 (P4). The place selected by leaders to establish the operations becomes a fundamental aspect, especially in the anticipation phase of an extreme event for organizations due the potential risk linked to the geographical location (Mucharraz, 2021). Simultaneously, the associated attributes of leadership are closely related to the place where the organization is located, as leadership is understood also in relationship to place (Grint, 2005; Jackson & Parry, 2018).

For the survival of an organization in a critical situation, continuity of business efforts becomes fundamental. As some research participants recommended, the agency for leaders is also reflected in the use of insurance policies and healthcare provision to protect employees, as well as evaluating and protecting buildings and the assets contained in them against natural disasters.

Leaders need to be aware and accept that the threat of an environmental event is constant and latent, and that action is required on a daily basis. In the emergency protocols, it is also required to consider the floating population in simulations, with special care given to vulnerable groups such as children, people with disabilities, and indigenous and foreign groups, which may not be familiar with a language or protocols and may not have the support of their networks. Furthermore, as participants highlighted, attendance controls and personnel records are important for being able to locate all people during an emergency.

Proposition 5 (P5). Technological capital is critical for organizations in the 21st century. The ability of the organization to manage social media is fundamental in the coping phase, as humanitarian aid can be provided and the affectation to the organizational community can be reduced, including the number of casualties.

One of the main considerations that leaders mentioned repeatedly was the use of information and technology to back up organizational data and provide connectivity, both as a precautionary measure to preserve information and for the survival of the organization.

Proposition 6 (P6). For an organization to cope effectively with an environmental crisis, interorganizational (Wang et al., 2009) and intersectoral coordination must be cultivated in the anticipation stage. Such coordination is activated when an environmental event happens, whereupon bonding with the immediate community is a source of solidarity and a potential source of relief through resources provision (Mucharraz, 2020).

The mentioned coordination of actions among different entities is focused on pursuing the common good in the middle of an emergency beyond the particular interests of each stakeholder. The emergent network in which the different actors participate is interwoven with the individual and collective resilience attributes, in which human, economic, social and political capital (Abramson et al., 2014, 44-45) are activated as a result of the crisis.

Proposition 7 (P7). Emotional action is as important as what Duchek (2020) described as cognitive and behavioral actions and may be associated with the development of organizational resilience as a whole. Addressing the grieving process in the organization (Sassón, 2004, 11) is a way to activate emotional action, and may lead to posttraumatic growth (Nava et al. , 2020).

Davis (2005) was critical of the resilience shown by Mexican public organizations and the way they responded to the country’s 1985 earthquake because they went back to business-as-usual almost immediately without contributing to the recovery process. To understand Davis’s (2005) criticism, it is necessary to clarify that resilience in this context involves the leaders’ acknowledgement of the grieving stage to accompany individuals dealing with the processing of loss.

For instance, some research participants mentioned the provision of psychological support for employees to help them in the emotional recovery process, provided both individually and in groups.

Proposition 8 (P8). Post-event growth in organizations is related as a process to their adaptability, promoted by learning experiences in which leaders and their teams reflect on what they did after a disaster, considering especially what worked well to be prepared for future occurrences. Some authors have transferred the concept of post-traumatic growth from individual to organizational analysis (Nava et al., 2020). This idea requires more work, as the reference to trauma would also need to be conceptualized as something that occurs to organizations as a whole and not only to single living beings.

The idea of conceptualizing resilience beyond simply «bouncing back» has been expressed by Paton and Johnston (2006), who referred to post-disaster resilience as an adaptive capacity to grow and develop that requires conscious effort. Along the same lines, disasters have a transformative potential: As «reorientation, the individual and collective negotiation of identity and belonging in the wake of disasters can be painful, stressful and confusing, but it can also be transformative» (Cox & Perry, 2011, 409). Some researchers have attributed post-traumatic growth (Leppma et al., 2018; Nava et al., 2020) to organizations that have been exposed to traumatic circumstances.

5. Discussion

Conceptual Model Analysis and Proposal

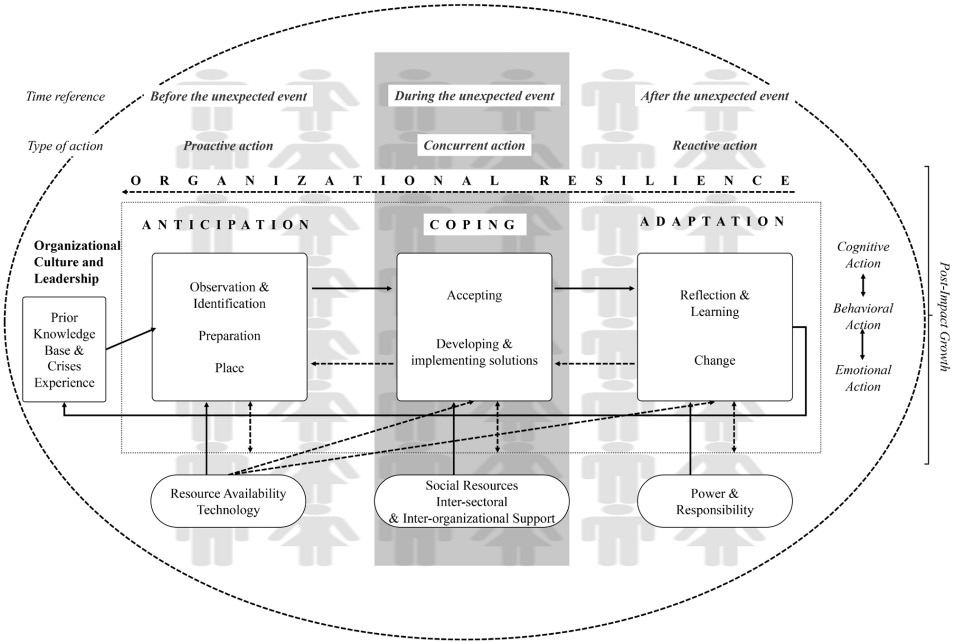

The eight propositions mentioned in the findings section were mapped in Duchek’s (2020) organizational resilience framework, as shown in Figure 1. The model was adapted to integrate the interpretation of the research participants’ analysis on how to develop resilience in organizations, as shown in Figure 2. One of the main considerations of this model is that the stages it presents need to be considered as a continuum and should not be read as a linear process. If the model were conceptualized three-dimensionally, the anticipation and adaptation stages would converge into a better representation in the form of a sphere, with a network formed by individuals in the center. The research participants were emphatic in ensuring that the most important element that organizations integrate, protect and keep alive are human beings, and other material elements as the buildings are only secondary.

Source: Adapted from Duchek, 2020, 10.

Figure 1 A capability-based conceptualization of organizational resilience

Source: adapted framework.

Figure 2 A capability-based conceptualization of organizational resilience

Actually, the boundaries observed in Duchek’s (2020) model outlining the anticipation, coping and adaptation phases are managed flexibly because an organization that is aware that it will face future crises naturally starts to anticipate other events while it reinforces its coping, learning and adaptation skills. Therefore, it would need to focus in parallel on the preparation phase, cope with the crisis for an extended period of time and take advantage of the lessons from the point of view of adaptation.

In Duchek’s (2020) framework (see Figure 1), the eight propositions are mapped and identified by consecutive numbers. The adapted version (see Figure 2) complements the original model and reflects the findings of this empirical study:

With the organizational resilience process completely mapped, there seems to be a gap in the literature regarding the role of leaders in disaster situations. The anticipation, coping and adaptation model described by Duchek (2020) provides a basis to guide future efforts by organizations and leaders about when and how to start dealing with crises caused by disastrous events such as earthquakes.

Besides the eight propositions identified and mapped in the model, it seems necessary to address the fundamental change that organizations take when facing a disaster. When the origin of change is bottom-up, it intersects with the role of leaders in catastrophic environments, as it is described in Proposition 3 (P3), where emergent leaders may help manage this type of transformation.

6. Conclusion

This research addressed the role of leaders in organizational disaster resilience after an extreme environmental event from an empirical perspective. The research process intended to answer the following question: How do business leaders develop resilience in their own organizations in a catastrophic scenario, particularly in the face of earthquakes? The phenomenon was based on the experience and testimony of Mexican leaders in the private sector after the 19S earthquake in Mexico City. Furthermore, existing resilience definitions were contrasted with empirical data to support the development of disaster resilience practices in organizations in the future.

The study involved 12 leaders from private-sector organizations affected by the 19S earthquake in Mexico City. Their testimony helped document their best practices, as well as apply and develop new theoretical insights on organizational resilience. The research questions were organized around appreciative inquiry principles.

The main conclusion from the study addresses the relevant role of business leaders in the anticipation, coping and adaptation stages needed to face disasters institutionally. In this sense, the traditional view of the leader as someone who guides or directs the response all by themselves is challenged as evidence points to the emergence of leaders who seem to have a fundamental role in the coping and recovery phases. The research method in this study allowed for a comparison between Duchek’s (2020) organizational resilience framework and the information collected from the research participants, resulting in eight propositions considered as insights and organized as recommendations for future events, as represented in the framework proposal (Figure 2). The opportunity to positively impact organizations in order to develop organizational resilience capacities is primarily stressed for the prior stage, referred to as the organizational culture, leadership, knowledge and experience, in the anticipation of future events that are likely to happen depending on the risks an organization is exposed to.

Finally, the introduction of constructs such as the role «emergent leaders» take during a disaster situation, the importance of addressing emotions and mental health aspects as part of the organizational culture considered as a protective element to face disasters successfully, contributes to the literature and to advance the transformation of businesses to become more sustainable institutions in the future.

7. Limitations of the Study and Future Research

This study represents the perspective of only 12 research participants in one major city in Latin America, and therefore has limitations in the generalization of the results. As a result of this exploratory research and its findings, new hypotheses can be formulated in the future. A bigger, more extensive study based on this study’s approach could further validate the applicability of this article’s recommendations and also test Duchek’s work. In this sense, future research should address how Duchek’s framework and these recommendations apply to larger organizations and different cultural contexts, also considering the historical and cultural aspects of each country of analysis. Business leaders also need to develop actionable guidelines, specific processes and key performance indicators for their organizations in order to make sure their capabilities are aligned to the development of a resilience framework that considers the readiness of their organizations and the development of this capacity over time.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)