Introduction

The order Boletales Gilbert was proposed for grouping all putrescent fungi with poroid hymenia (Gilbert, 1931). Currently, the Boletales includes also agaricoid, sequestrate and resupinate fungi classified in 17 families, and more than 1316 species in the world (Binder and Hibbett, 2006; García-Jiménez et al., 2013). Most species of Boletales are ectomycorrhizal and grow in association with members of Pinaceae, Fagaceae, Salicaceae, Betulaceae, Fabaceae, Nyctaginaceae, and Polygonaceae, but there are also some saprotrophic. Some Boletales have both economic and ecological importance as many species are edible (Henkel et al., 2002; Ortiz-Santana et al., 2007; García-Jiménez et al., 2013) and they also play a central role in translocation of nutrients from soil to different hosts in the forest.

Several Boletales surveys have been conducted in Central and Northern Mexico (García and Castillo, 1981; García et al., 1986; Singer et al., 1990, 1991, 1992; González-Velázquez and Valenzuela, 1993, 1995, 1996; García-Jiménez, 1999; García-Jiménez and Garza-Ocañas, 2001; Cázares et al., 2008; García-Jiménez et al., 2013; Baroni et al., 2015). However, researchs on Boletes from tropical forest and coastal vegetation are still scarce. Only 11 species of Boletales have been recorded from Quintana Roo (Chío and Guzmán, 1982; Guzmán, 1982, 1983; Pérez-Silva et al., 1992; Singer et al., 1992; García-Jiménez, 1999; Chay-Casanova and Medel, 2000; Pompa-González et al., 2011) (Table 1).

Table 1 Boletales of Quintana Roo, Mexico

| Taxa | Habitat | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Boletaceae | ||

| Boletellus cubensis (Berk. & M.A. Curtis) Singer | Urban Gardens, disturbed vegetation | Singer et al. (1993) |

| Octaviania ciqroensis Guzmán | Tropical forest | Guzmán (1982) |

| Pulveroboletus aberrans Heinem. & Gooss.-Font. | Tropical forest | Guzmán (1983) |

| Xerocomus caeruleonigrescens Pegler | Tropical forest | García-Jiménez (1999) |

| Xerocomus coccolobae Pegler | Coastal vegetation, urban gardens | This work |

| Xerocomus cuneipes Pegler | Tropical forest | García-Jiménez, 1999 |

| Boletinellaceae | ||

| Phlebopus brasiliensis Singer | Lowland forest, disturbed vegetation | This work |

| Phlebopus colossus (R. Heim) Singer | Tropical forest | Guzmán (1983) |

| Gyrodon intermedius (Pat.) Singer | Tropical forest | Chío and Guzmán (1982) |

| Sclerodermataceae | ||

| Scleroderma albidum Pat. & Trab. | Tropical forest | Pérez-Silva et al. (1992) |

| Scleroderma areolatum Ehrenb | Tropical forest | Pérez-Silva et al. (1992) |

| Scleroderma bermudense Coker | Tropical forest, urban gardens | Guzmán et al. (2013) |

| Scleroderma nitidum Berk. | Lowland forest, disturbed vegetation | This work |

| Scleroderma sinnamariense Mont. | Tropical forest | Pompa-González et al. (2011) |

| Suillaceae | ||

| Suillus decipiens (Peck) Kuntze | Pine savanna | This work |

Boletales are scarce in well-established tropical dry forest from Northern Yucatan Peninsula, (Hasselquits et al., 2011), but appear to be common in disturbed vegetation from Quintana Roo according to our observations. It is possible that Boletales form mycorrhizas with some tree species characteristic from early successional vegetation stages, for example Coccoloba spicata Lundell and Lysiloma latisiliquum (L.) Benth., this process has been reported by Singer and Morello (1960). However, there are poorly explored ecosystems in southern Quintana Roo, like the lowland savanna with Pinus caribaea Morelet and exuberant tropical forests near the Belize’s frontier that have been recognized by mycologists as a well conserved area with a high richness of fungal species (López et al., 2011). The aim of this paper is to provide information about Boletales of Quintana Roo and set the foundations of new mycological surveys in the Mexican tropical forest.

Materials and methods

The explorations were made in the state of Quintana Roo, in the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico in the year period 2014-2017 (Figure 1). The collection sites were dominated by lowland forests with Coccoloba diversifolia Jacq., Gymnanthes lucida Sw., Chrisobalanus icaco L., and Gymnopodium floribundum Rolfe; tropical forest dominated by Sapotaceae and Fabaceae, lowland savanna with P. caribaea, C. diversifolia and G. floribundum and disturbed vegetation with Coccoloba sp. and L. latisiliquum. Methods of Lodge et al. (2004) were followed for sampling and collecting macrofungi. Hand-cut sections were mounted in KOH 5% for microscopical descriptions of the species. The handbook of color of Kornerup and Wanscher (1978) was used for identifying color of basidiomata. A key of Boletales species occurring in Quintana Roo is given. The specimens were deposited at the “José Castillo Tovar” herbarium in the Instituto Tecnológico de Ciudad Victoria (ITCV).

Results

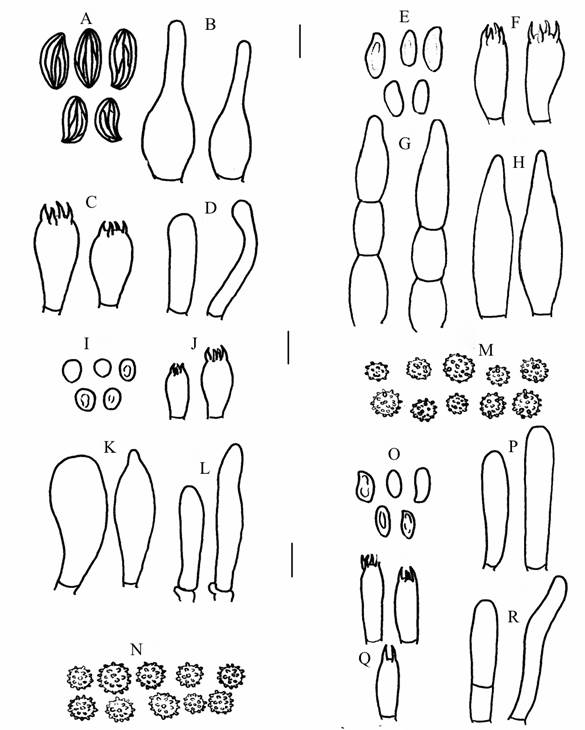

Six species belonging to four families (Boletaceae, Boletinellaceae, Sclerodermataceae and Suillaceae) were studied. A taxonomic description, discussion and illustrations are provided for each species (Figures 2 and 3). All records except Boletellus cubensis (Berk. & M.A. Curtis) Singer and Scleroderma bermudense Coker are new records from Quintana Roo. Most of the species were registered in disturbed vegetation, lowland forest or urban gardens.

Figure 2 Studied species. A. Boletellus cubensis, B. Xerocomus coccolobae, C. Phlebopus brasiliensis, D. Scleroderma bermudense, E. Scleroderma nitidum, F. Suillus decipiens.

Figure 3 Microscopical features. A-D: Boletellus cubensis. A. Basidiospores, B. Cheilocystidia, C. Basidia, D. Elements of pileipellis. E-H: Xerocomus coccolobae. E. Basidiospores, F. Basidia, G. Elements of pileipellis, H. Cheilocistidia. I-L: Phlebopus brasiliensis. I. Basidiospores, J. Basidia, K. Cheilocystidia, L. Elements of pileipellis. M: Scleroderma bermudense. Basidiospores. N: Scleroderma nitidum. Basidiospores. O-R: Suillus decipiens. O. Basidiospores, P. Cheilocystidia, Q. Basidia, R. Elements of pileipellis. Scale bar: 10 µm.

Description of species

Boletellus cubensis (Berk. & M.A. Curtis) Singer, Farlowia 2(1): 127 (1945)

Pileus 30-60 mm, convex, areolated, covered with greyish tomentose cracks (30C6), being more conspicuous on the center, background whitish or pastel red (9A4) to dull red (9B4) or greyish green tints (30C6), dry texture, appendiculate, with veil rests projecting from margin. Tubes yellowish, 5 mm long, not bruising. Pores angular, radially arranged, up to 1 mm diameter, yellowish (30A7), adnate, not bruising. Stipe 81-120 × 7-9 mm, solid, with a bulbous base, fully covered by greyish (30C6) conspicuous scales, background color white but reddish (9A4) at the apex. Context 9 mm to the disk, whitish, not bruising. Odor and taste indistinct.

Basidiospores 13.2-21.6 × 6.3-8.1 μm (L=17.6 W=7.21, Q=2.42, N=30) fusoid or subfusoid, with suprahilar depression, longitudinally winged, with transverse striation, light brown and yellow in KOH. Basidia 26.1-35.4 × 12.0-17.0 μm, clavate, hyaline in KOH, four-spored, thin walled. Pleurocystidia 50.0-62.5 × 9.0-14.0 μm, ventricose, fusoid, hyaline in KOH, thin-walled. Cheilocystidia 48.0-58.5 × 9.0-14.0 μm, ventricose, fusoid or rostrate, hyaline in KOH, sometimes with incrustated pigments, thin-walled. Hymenophoral trama bilateral with a medium strata and lateral strata composed by cylindrical hyphae 2.9-5.7 µm, hyaline to pale yellowish in KOH, thin-walled. Pileipellis composed by interwoven cylindrical hyphae, yellowish color with terminal cells, 27.7-61.9 × 5.0-9.4 μm, clavate, cylindrical. Stipitipellis composed by caulocystidia 20.0-61.3 ×10.2-15.0 µm, clavate or ventricose, hyaline in KOH.

Studied material: Quintana Roo: Othon P. Blanco, Laguna Guerrero village, de la Fuente 47, October 26, 2014 (ITCV). Chetumal, García and López 5471, January 15, 1988 (ITCV). Bacalar, Bacalar city, de la Fuente and Barboza 197, October 19, 2015 (ITCV).

Distribution: Mexico, Belize, Costa Rica, Cuba (Ortiz-Santana et al., 2007), Martinique, and Guadeloupe (Pegler, 1983). This species was described from Quintana Roo by Singer et al. (1992).

Discussion: This species can be recognized by the areolated pileus and the grey scales on the stipe. Recent collections from different localities were performed. The material agrees with those described by Ortiz-Santana et al. (2007). Boletellus cubensis can be often found on secondary forest and on road edges, it might form mycorrhizas with Polygonaceae and Sapotaceae. Pileus with appendiculate margin was considered by Pegler (1983), but was not described by Singer et al. (1992) nor Ortíz-Santana et al. (2007).

Xerocomus coccolobae Pegler, Kew Bull. Addit. Ser. 9: 576 (1983)

Pileus 41-59 mm, convex, brown color (7F8), dry, minutely tomentose, sometimes cracked showing pale brown context (5A3), entire margin. Tubes 3-8 mm, yellowish (30A7), decurrent, not separating when cutting, bruising greenish blue when injured. Pores angulose, wide (>1.5 mm), yellowish (30A7), bruising blue when injured. Stipe 40-59 × 4-6 mm, solid, fibrilous, slender, pale brown (5B4) whitish near the base. Contex 7-12mm whitish bruising pale yellow at pileus, blue near the tubes and pinkish red near the base of stipe. Odor and taste fungoid. Yellowish basal mycelial present.

Basidiospores 10.0-13.0 × 4.8-6.0 µm (L=11.60, W=5.13, Q=2.25, N=30), fusiform to subfusiform, with suprahilar depression, thin walled, olive brown in KOH. Basidia 24.0-30.5 × 10.5-13.7 µm, clavate, four-spored, with granular content. Pleurocystidia 60.0-94.0 × 7.5-10.0 µm, ventricose, hyaline in KOH, thin-walled. Cheilocystidia 39.0-60.0 × 10.2-15.0 µm, ventricose, sometimes rostrate, hyaline in KOH, thin-walled. Hymenophoral trama bilateral, xerocomoid, with a medium strata and lateral strata composed cylindrical hyphae 2.5-12.0 µm diameter. Pileipellis composed by erected chains of globose or elongated cells, with terminal cells 26.3-42.7 × 7.3-11.5 µm, clavate, ventricose or cylindrical, hyaline in KOH, thin-walled. Caulocystidia 26-35 × 11-14 µm, cylindrical, clavate or fusoid, hyaline, thin-walled.

Studied material: Quintana Roo: Othon P. Blanco, gardens of Instituto Tecnológico de Chetumal (ITCh), de la Fuente 37, October 14, 2014 (ITCV). Chetumal, Boulevard Bahía, de la Fuente 41, November 30. 2014 (ITCV). Santa Helena village, de la Fuente 254, January 08, 2017 (ITCV).

Distribution: Martinica and Mexico (Veracruz and Yucatan) (Pegler, 1983; García-Jiménez, 1999).

Discussion: This species can be recognized by the wide pores, the brown stipe and the slender, whitish stipe. Our description agrees with Pegler (1983) and García-Jiménez (1999). This is one of the tropical species in America. The original description from Martinica Island in the Lesser Antilles agrees with the material examined from Veracruz and Yucatan. This species might grow at coastal zones on the East and on the Caribbean zone in Mexico associated with C. spicata and C. uvifera, as described by Pegler (1983).

Phlebopus brasiliensis Singer in Singer, Araujo & Ivory, Beih. Nova Hedwigia 77: 43 (1983)

Pileus reaching 60 mm, convex, dark brown to brown (5F3-5D8), dry texture, minutely tomentose, sometimes minutely cracked when dry, with projecting margin, pale brown and entire. Tubes 4 mm, adnate, light cream color (5A2-5A3) not bruising. Pores small (< 1mm), cream to pale yellow to cream (5A2-5A3), rounded, not bruising. Stipe 21 × 30 mm, solid, with bulbous base, cream at the apex (5A2), dark brown at the base (5F4), dry, smooth, slightly bruising orange when injured. Context whitish to cream to pale brown (5A2) irregularly bruising brown when cut. Odor and flavour indistinct

Spores 4.5-7.0 × 3.5-5.5 μm (L=6.20, W=4.56, Q=1.35, N=30) ovate, smooth, thin-walled, light brown in KOH. Basidia 16.0-24.5 × 7.0-10.0 μm, clavate, four-spored, hyaline in KOH. Cheilocystidia 27.5-49.2 × 1.2-13.8 μm, clavate, fusoid with short neck, not abundant, hyaline in KOH, thin-walled. Hymenophoral trama bilateral, with medium strata and lateral strata composed by cylindrical hyphae 3.5-7.5 μm diameter, hyaline to pale yellowish in KOH, gelatinized. Pileipellis composed by interwoven trichodermium of hyaline yellowish in KOH hyphae, reaching 8.0 μm diameter, with terminal cells, 35.6-62.2 × 6.0-8.5 µm, cylindrical, with rounded, lanceolated apex, with clamp connections at base. Stipitipellis with interwoven, hyaline in KOH, thin-walled hyphae, with terminal cells, 38.5-43.0 × 6.0-12.0 μm diameter, cylindrical.

Studied material: Quintana Roo: Felipe Carrillo Puerto, Señor village, in lowland forest, de la Fuente and Francisco Chan 46, October 10, 2014 (ITCV). Chiapas: Unión Juárez, Guzmán 30774, October 18, 1997 (ITCV).

Distribution known: Mexico (Chiapas, Jalisco and Veracruz) and Brazil (Singer et al., 1983; García-Jiménez and Garza-Ocañas, 2011).

Discussion: This species can be recognized in field by the dark brown pileus, the small rounded pores and the bulbose stipe. The material agrees with the described by García-Jiménez (1999) and Singer et al. (1983), but with wider cheilocystidia. Singer et al. (1983) reported mucronate to fusoid cheilocystidia, meanwhile García-Jiménez (1999) reported clavate cheilocystida. Our material has both cheilocystidia shapes. Guzmán (1983) recorded P. colossus in Quintana Roo, that species differs in the context bruising blue when cut and the pileus size, being P. colossus bigger. Phlebopus mexicanus Cifuentes, Cappello, T. J. Baroni & B. Ortiz is similar tropical species, but it differs in the bluish reaction when cut (Baroni et al., 2015).

Scleroderma bermudense Coker, Mycologia 31(5): 624 (1939)

Basidiomata 15-30 mm, subhypogeous, sessile, with peridium whitish to pale greenish (30D8) or pale brown (5E5), covered by conspicuous dry scales or cracks. Stelliform when mature, showing to 4-7 branches. Context whitish to brownish. Dusty gleba, dark gray (5F1) in young basidiomata to purplish to brown (5E4) in immature specimens. Whitish color rizomorphs are presents.

Basidiospores 6.6-8.9 × 6.2-8.2 μm (L=5.95, W=5.60, Q=1.06, N=30), echinulated, with a poor developed reticulum, 1.0 μm long, thick walled (1.0 μm), light green in KOH. Basidia no observed. Peridium composed by interwoven, hyaline, thick walled hyphae, 3.0-5.0 μm diameter, with rounded apex. Clamp connections presents.

Studied material: Quintana Roo: Othón P. Blanco, Chetumal on urban gardens, de la Fuente 43, September 30, 2014 (ITCV). Laguna Guerrero village on lowland forest, de la Fuente 264, January 11, 2017 (ITCV). Luis Echeverría village, on coastal vegetation, de la Fuente 295, January 17, 2017 (ITCV).

Distribution: Mexico and Caribbean countries (Guzmán et al., 2013).

Discussion: Scleroderma bermudense can be recognized by the stelliform dehiscent basidioma. It is a very common species that can grow forming mycorrhizas with Coccoloba species, mainly C. spicata on urban gardens and C. uvifera in sand dunes and coastal vegetation. Our description agrees with Guzmán et al. (2013), being our material bigger and with peridium that does not brush red color when bruised. Scleroderma albidum Pat. & Trab. is a similar species, but has bigger spores and lacks clamp connections. Scleroderma sinnamariense Mont., another similar species, shows a sulfur yellow peridium context and a poor developed pseudostipe (Guzmán, 1970). Those species have been previously recorded from northern Quintana Roo (Pompa-González et al., 2011). Guzmán (1983) recorded S. sinnamariense Mont. and S. stellatum Berk. from Quintana Roo; those materials belong to S. bermudense according to Guzmán et al. (2013).

Scleroderma nitidum Berk., Hooker's J. Bot. Kew Gard. Misc. 6: 173 (1854)

Basidiomata 7-14 mm, globose to subglobose, subhypogeous, sometimes with a short pseudostipe, up to 2 mm long. Peridium thin and fragile, pale brown (5A3), densely covered by minutely dark brown scales (5D8), being more conspicuous and big near the base or pseudostipe. Apical pore present, reaching 3 mm in diameter never stelliform. Context cream to brownish. Gleba greyish and compact in young specimens, olive brown and powdery in mature basidiomata with yellowish to whitish veins. Odor and taste rubbery.

Basidiospores 6.0-8.5 × 5.0-7.5 µm (L=7.18, W=6.81, Q=1.05, N=30), echinulated, without reticulum, thin-walled, light brown to yellowish in KOH. Basidia no observed. Peridium composed by interwoven, hyaline, thin-walled hyphae, reaching 7.0 µm without clamp connections. Scales hyphae 11.0-25.0 × 6.0-12.0 µm, globose to subglobose, hyaline, collapsed, yellowish to brownish in KOH.

Studied material: Quintana Roo: Othón P. Blanco, Laguna Guerrero village, on lowland forest under C. diversifolia and G. floribundum, de la Fuente 271, January 11, 2017 (ITCV).

Distribution: Mexico (Campeche), Costa Rica, Cuba, and Nepal (Guzmán et al., 2013).

Discussion: This species can be recognized by the dark patches in the peridium, the subhypogeus habit and the rubbery smell. Our description agrees with Guzmán et al. (2013). This species seems to form mycorrhizas with Coccoloba or Gymnopodium trees; they have a great diversity of mycorrhizal fungi (Bandala and Montoya, 2015). Scleroderma nitidum seems to prefer lowland forest, growing near paths and disturbed vegetation. Scleroderma nitidum was considered in a different genus as Veligaster nitidum (Berk.) Guzmán & Tapia due to the blackish patches around the apex of the pseudostipe, but was later reconsidered by Guzmán et al. (2013) as synonym of Scleroderma.

Suillus decipiens (Peck) Kuntze, Revis. gen. pl. (Leipzig) 3(2): 535 (1898)

Pileus 15-70 mm, convex to applanate, covered of fibrilous scales, cinnamon brown (5C8), slightly more conspicuous at disc, background pallid orange to pale brown (5A4), dry texture, entire margin covering hymenophore in young basidiomata. Tubes subdecurrent, yellowish, 4-6 mm long, not bruising. Pores angular, boletinoid, yellowish to pale brown (5A3-5A4), not bruising. Stipe 30-70 ×10-12 mm, solid, equal or sometimes with clavate base, without glandular dots, peach color at apex (6B7) orange at the base (5C7), dry texture, smooth. Basal mycelia present, orange color. Ring present only in young basidiomata. Context 7-12 mm, pale brown, not bruising. Odor and taste fungoid. Spores 7.8-8.9 × 3.2-4.0 μm (L=9.57, W=4.03, Q=2.37, N=30), fusiform to subfusiform, smooth, with suprahilar depression, thin walled, light brown in KOH. Basidia 19.7-25 × 5-6.7 μm, clavate, four-spored, hyaline in KOH. Pleurocystidia 27.2-44.9 × 6.1-7 μm, abundant, cylindrical or almost capitated, hyaline or with yellowish brown granular content in KOH, thin-walled. Cheilocystidia with similar size and shape to pleurocystidia. Hymenophoral trama bilateral, with medium strata and lateral strata composed by cylindrical and inflate hyphae 2.0-8.0 μm, with incrusted elements and brown contents in KOH, thin-walled. Pileipellis composed by erect hyphae, forming chains with lanceolate or cylindrical terminals cells, 37.7-52.1 × 9.1-14.8 μm, hyaline or sometimes with yellowish intracellular content in KOH. Stipitipellis composed by caulocystidia 24-54 × 6-9 µm, clavate, with yellowish and brown content in KOH, thin-walled.

Studied material: Quintana Roo: Othon P. Blanco, Jaguactal savanna, de la Fuente 51, September 10, 2014 (ITCV); de la Fuente 290, January 17, 2017 (ITCV).

Distribution: USA, Mexico (Chiapas), Belize, Costa Rica, Nicaragua Dominican Republic, and Cuba (Singer et al., 1983; García-Jiménez, 1999, Ortíz-Santana et al., 2007).

Discussion: This species can be recognized by the fibrilous brown scales, the absence of glandular dots in the stipe and by growing under Pinaceae species. Our material agrees with the descriptions provided by Singer et al. (1983), García-Jiménez (1999) and Ortíz-Santana et al. (2007). This species is similar to S. salmonicolor (Frost) Halling, but differs from S. decipiens in the lacking of glandular dot and squamose pileus. Other related species is S. tomentosus Singer, but this species had a bluish reaction when injured. The three species occur in pine savanna in Belize (Ortíz-Santana et al., 2007), but only S. decipiens has been recorded in Jaguactal savanna in Quintana Roo. This is a common species under P. caribaea in the jaguactal savanna and also in Belize (Kropp, 2001).

Key to Boletales species occurring in Quintana Roo

1a. Basidiome pileate-stipitated …………………………………………………........................………………7

2a. Gleba chambered, whitish to pale brownish……………………….......……Octaviania ciqroensis

2b. Gleba dusty, never chambered………………………………………………………………………………………...3

3a. Clamp connections present………………………………………………………………………………..............4

3b. Clamp connections absent……………………………………………………………………………………....………5

4a. Context sulfur yellow…………………………………………...….…………..Scleroderma sinnamariense

4b. Context whitish to brownish………………….......….......…….…………Scleroderma bermudense

5a. Basidiospores 13-18 µm diameter………………………...........………………Scleroderma albidum

5b. Basidiospores smaller than 13-18 µm diameter.……………………………...............……………..6

6a. Basidiospores (9)10-15(18) μm diameter…………………..…............Scleroderma areolatum

6b. Basidiospores (6)7-11 μm diameter………………………...........……………Scleroderma nitidum

7a. Pileus powdery…………………………………………………...................……Pulveroboletus aberrans

7b. Pileus never powdery………………………………………………………....................…...………….…….8

8a. Stipe thick and with bulbose base……………………………………………………..................……….9

8b. Stipe slender without bulbose base………………………………………………...............……..…….10

9a. Pileus large, over 100 mm, bruishing blue…………………………….......….Phlebopus colossus

9b. Pileus smaller, never bruishing blue……………………………...............Phlebopus brasiliensis

10a. Spores ornamented…………………………………………………………………….......................…….11

10b. Spores smooth ………………………………………………………………………..........................…….14

11a. Spore surface longitudinally ridged………………………….........……………Boletellus cubensis

11b. Spore surface bacillated.................................................................................12

12a. Stipe contex bruishing pale red……………………………………….........Xerocomus coccolobae

12b. Stipe context bruishing blue………………………………………………………………....................13

13a. Pileus with olivaceus and reddish tones………………………..Xerocomus caerulonigrescens

13b. Pileus with yellowish and pinkish tones………………………………........Xerocomus cuneipes

14a Spores ovate…………………….………………………………………..................Gyrodon intermedius

14b. Spores fusoid……………………..…………………………………………...................Suillus decipiens

Conclusion

Boletales diversity is scarce when compared with other fungal groups in Quintana Roo like Agaricales or Polyporales. Nevertheless some interesting species can be found mostly associated with Polygonaceae trees. The lowland forest and urban gardens show an interesting diversity of Boletales species, growing associated with Coccoloba trees. We suggest continuing with the taxonomic studies in tropical Boletales. We also suggest more ecological and taxonomic studies in the pine savanna due the importance of the mycorrhizal fungi in this threatened pine population.

nova página do texto(beta)

nova página do texto(beta)