Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most frequently diagnosed neoplasm and the leading cause of death attributed to cancer in women worldwide. In 2020, there were approximately 2.2 million new cases of BC and 684,000 deaths from this disease1,2. This represents 25% of new cancer diagnoses and 16% of cancer deaths in women worldwide1,2. It is estimated that the incidence of BC will steadily increase in the next two decades2. Mexico is not the exception, a constant increase in both incidence and mortality has been reported during the last three decades3.

The epidemiology of BC varies according to the human development index. Although BC incidence and mortality are increasing worldwide, survival is inferior in low- and middle-income countries compared to high-income countries1-6. In limited resource settings, over half of the women with BC have locally advanced or metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis7. In comparison, in high-income countries, these stages represent less than 30% of diagnoses8. One of the main causes associated with this disparity is a delay of more than 90 days from the diagnosis of BC to the beginning of treatment reported in some low- and middle-income countries9,10. For example, the median interval between the onset of symptoms and treatment initiation is 4.5 months in Colombia11, 7 months in Mexico4, and 7.6 months in Brazil12. This data contrasts with that reported in France and the United States where the medians are 24 and 48 days, respectively13,14. In Latin American countries’ health systems, the greatest delay occurs between the first consultation and the beginning of treatment, specifically in the diagnosis interval4,11,12. Moreover, it has been documented that Latin American women seek care just as soon as women in developed countries, with a median of 9 to 15 days; however, they face long delays before their diagnosis is confirmed. Thus, medical errors among primary care providers, lack of clinical suspicion for overt BC symptoms and signs, and long waiting times for medical appointments have been attributed as some of the main causes for health system delays in BC diagnosis and treatment. Yet, a limited number of studies have been aimed at understanding this complex topic10.

To our knowledge, there are no published studies reporting the perception of healthcare providers on the delays in BC care in Mexico. The objectives of this study were to understand the perception of delays and barriers in BC care, to explore physicians knowledge about the existence of referral pathways for the care of patients with clinical suspicion and confirmed diagnosis of BC in their affiliated institutions, to assess physicians’ action plan in case of BC suspicion or diagnosis, and to determine if there is an association between physicians’ awareness of referral pathways and perceived time to BC treatment initiation.

Materials and methods

A web-based multiple-choice survey was conducted among general practitioners and specialists who carry out their medical practice in Mexico. Participants were recruited through an invitation using healthcare providers’ social media groups on Twitter, Facebook and WhatsApp. Data was collected between July 5 and 12, 2022. Participants answered anonymously and there was no cost or compensation for participating in this study.

The survey was developed by the study investigators (Appendix 1). It consisted of a total of 20 questions that inquired about physicians’ sociodemographic data (age, specialty and city of medical practice), perception of delays and barriers in BC care, knowledge about referral pathways in their affiliated institution, and action plan in case of BC suspicion or diagnosis (diagnostic tests ordered and specialties referral). Participants were asked whether they worked in the public or private healthcare sector.

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the data. A chi-squared test was used to assess if the lack of awareness of referral pathways was associated with the perceived interval from symptom onset to treatment initiation. The data was analyzed using the statistical program SPSS version 25.

Results

Participant demographics

A total of 785 participants completed the survey. Of these, 765 answers were analyzed after excluding 20 respondents who did not meet the study criteria (n=18 were not medical doctors and n=2 lived outside of Mexico). Median age was 41 years with a range of 24 to 83 years. Participants were most frequently gynecologists (n = 147 [19%]), general practitioners (n = 124 [16%]) and family physicians (n = 111 [15%]). 271 (35%) participants reported carrying out their clinical practice in the public sector, 268 (35%) in the private sector, and 226 (30%) in both (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1 Sociodemographic Characteristics (n = 765)

| Characteristics | Measurement |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 41 (24-83) | |

| < 30 years old | 40 (5.2) |

| 30-39 years old | 284 (37.2) |

| 40-49 years old | 225 (29.4) |

| 50-59 years old | 109 (14.2) |

| 60-69 years old | 88 (11.5) |

| > 70 years old | 19 (2.5) |

| Specialty | |

| Anesthesiology | 23 (3.0) |

| General Surgery | 21 (2.7) |

| Oncology-related specialties | 60 (7.8) |

| Obstetrics and Gynecology | 147 (19.2) |

| Imaging | 14 (1.8) |

| Emergency Medicine | 23 (3.0) |

| Family Medicine | 111 (14.5) |

| General Medicine | 124 (16.2) |

| Internal Medicine | 39 (5.1) |

| Internal Medicine Subspecialties | 54 (7.1) |

| Pathology | 44 (5.8) |

| Pediatrics | 26 (3.4) |

| Other non-surgical Specialties | 46 (6.0) |

| Other Surgical Specialties | 33 (4.3) |

| Health care system | |

| Public | 271 (35.4) |

| Private | 268 (35.0) |

| Both | 226 (29.5) |

| Public institutions where they work | |

| Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social | 319 (64.2) |

| Instituto de Seguridad y Servicios Sociales de | 34 (6.8) |

| los Trabajadores del Estado | |

| Instituto de Salud Estatal | 11 (2.2) |

| Secretaria de Salud | 109 (21.9) |

| Other | 24 (4.8) |

| Level of care of the institution where they work | |

| Primary care | 162 (32.6) |

| Secondary care | 215 (43.3) |

| Tertiary care | 120 (24.1) |

Data is represented as a percentage (%) or a median (range).

Table 2 State of practice (n = 765)

| State | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Aguascalientes | 4 | 0.5 |

| Baja California | 7 | 0.9 |

| Baja California Sur | 14 | 1.8 |

| Campeche | 2 | 0.3 |

| Chiapas | 5 | 0.7 |

| Chihuahua | 70 | 9.2 |

| Ciudad de Mexico | 95 | 12.4 |

| Coahuila | 47 | 6.1 |

| Colima | 2 | 0.3 |

| Durango | 15 | 2.0 |

| Estado de Mexico | 20 | 2.6 |

| Guanajuato | 7 | 0.9 |

| Guerrero | 3 | 0.4 |

| Hidalgo | 5 | 0.5 |

| Jalisco | 53 | 6.9 |

| Michoacan | 10 | 1.3 |

| Morelos | 3 | 0.4 |

| Nayarit | 2 | 0.3 |

| Nuevo Leon | 161 | 21.3 |

| Oaxaca | 1 | 0.1 |

| Puebla | 42 | 5.5 |

| Queretaro | 6 | 0.8 |

| Quintana Roo | 2 | 0.3 |

| San Luis Potosi | 2 | 0.3 |

| Sinaloa | 61 | 8.0 |

| Sonora | 12 | 1.6 |

| Tabasco | 1 | 0.1 |

| Tamaulipas | 9 | 1.2 |

| Tlaxcala | 2 | 0.3 |

| Veracruz | 65 | 8.5 |

| Yucatan | 5 | 0.7 |

| Zacatecas | 33 | 4.3 |

Delays in BC care

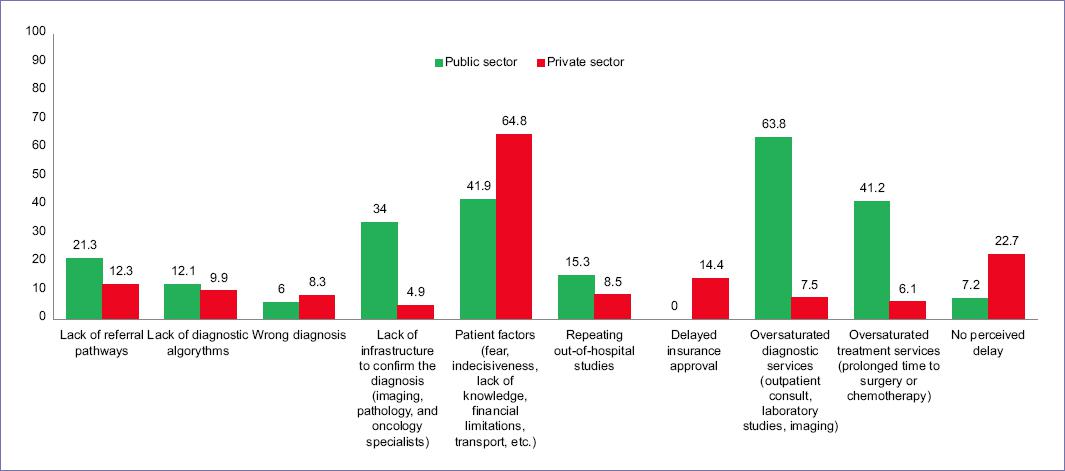

When asked about their perception of the interval between symptom onset and treatment initiation in their institutions, 254 (51%) participants from the public and 387 (78%) from the private sector estimated an interval of less than 90 days. Delays of more than 90 days were estimated by 87 (18%) physicians in the public and 11 (2%) in the private sector. The rest of the participants, 156 (31%) from the public and 96 (19%) from the private sectors, reported not knowing this information (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 "What is the estimated time between symptom onset and treatment initiation for breast cancer?". A: Public sector; B: Private sector.

When comparing the different levels of care in the public sector (n = 497), primary care providers significantly perceived delays of less than 90 days (n = 104 [64%]) more often than secondary and tertiary level care providers (n = 150 [45%]) (OR 0.45, 95%CI 0.30 -0.66, p < 0.001). Perception of delays did not differ significantly in the public sector when comparing oncological specialists with other physicians (p = 0.19). Finally, comparing the perceived delays of more than 90 days in the public sector across regions (North, Center and South) and across different public health systems did not yield any significant differences (p= 0.61 and p = 0.39, respectively).

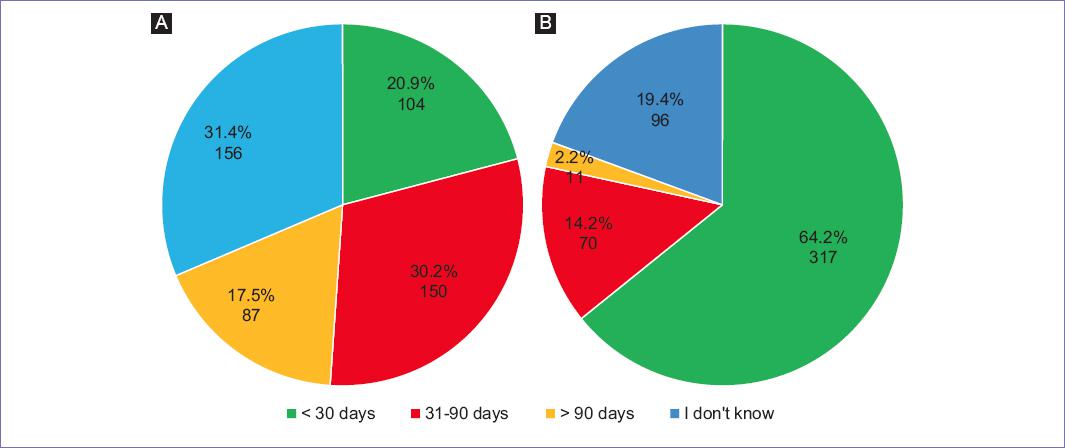

Regarding the factors associated with delays in BC care, 317 (64%) physicians in the public sector considered that the main barriers to care were the saturation of services (outpatient consultation, laboratory, imaging, surgery, chemotherapy units), and 205 (41%) the lack of infrastructure (imaging equipment, laboratory studies, pathology and oncology specialists). In the private sector, 320 (65%) participants mentioned patient factors (fear, apathy, ignorance, financial limitations and transportation constraints) as the main contributors. Only 38 (7%) physicians in the public and 112 (23%) in the private sector referred no barriers for timely BC care (Fig. 2).

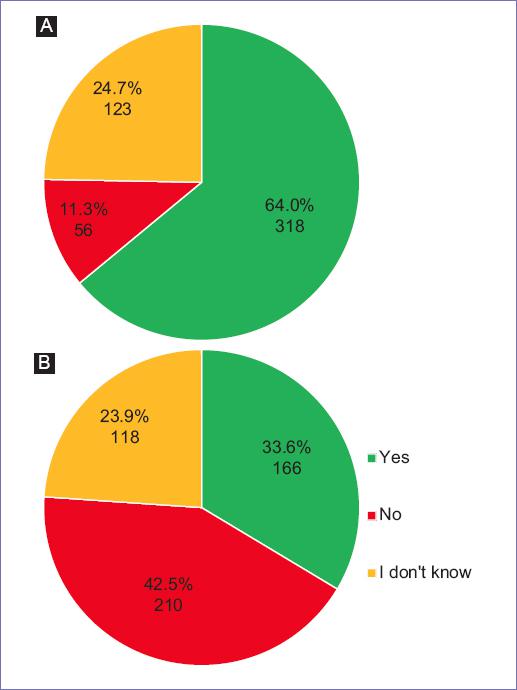

Referral pathways for suspected and confirmed BC

In total, 179 (36%) participants from the public and 328 (66%) from the private sector were unaware of the existence of referral pathways for suspected and confirmed BC in their institutions (Fig. 3). A significant association was found between the lack of knowledge about the referral pathways and longer perceived time from the onset of symptoms to treatment (OR 5.96, 95%CI 3.95-9.00, p < 0.001).

Figure 3 "Does your institution have an established referral pathway for patients with suspected or confirmed breast cancer?". A: Public sector; B: Private sector.

Regarding physicians’ plan of action, the next diagnostic step after encountering breast findings suggestive of malignancy was requesting breast imaging studies by 375 (75%) physicians in the public and 362 (73%) in the private sector (Fig. 4). As for the specialist that patients with BC suspicion were referred to, physicians in the public sector indicated a higher proportion of referrals to gynecology (n = 193 [39%]), whereas those in the private sector referred to surgical oncology more frequently (n = 180 [36%]). Once BC diagnosis was confirmed, participants made referrals to surgical oncology (n = 199 [40%] and n = 226 [46%]) and medical oncology (n = 197 [40%] and n = 158 [32%]) in the public and private sectors, respectively (Appendix 2).

Discussion

Delay in BC care has been associated with diagnosis at more advanced stages, and therefore, decreased survival13. Accordingly, international agencies such as the World Health Organization have established that the interval between the onset of symptoms and treatment initiation should be less than 90 days to reduce delays in care, avoid loss to follow-up, and optimize treatment efficacy15. In Mexico, like other developing countries, it has been reported that BC patients in the public sector face delays of more than 90 days before receiving care4,9. Understanding the barriers to timely BC diagnosis and treatment in our country is crucial for the implementation of national guidelines, infrastructure development, and allocation of resources to reduce health system delays, and ultimately contribute to BC downstaging. This study provides a first insight into the perception that healthcare providers have about BC care in Mexico.

These results show that only 17% of physicians in the public and 2% in the private sector perceive delays in BC care greater than 90 days. There is no significant difference when comparing oncological specialists with other physicians. However, delays are more often perceived by secondary and tertiary level care providers in the public sector compared to primary care physicians. There are no other studies focused on understanding the physicians’ perspectives in Mexico, and the only available evidence relies on quantitative data on the patients’ experienced intervals for BC care.

A previous study focused on the patient’s delays at four public referral centers in Mexico City showed that the interval from the onset of symptoms to treatment initiation in women with BC was 4 to 14 months, with a median of 7 months4. The same study reported that 90% of the delays were greater than 3 months and 57% were greater than 6 months. In addition, it highlighted that the greatest delay occurred between the first consultation and diagnosis (median of 4 months). The reason why physicians in our study perceive short delays contrasts with what has been previously reported by the patients’ experiences calculated using their healthcare records in this previous study. It is important to note that the objectives and the methodologies used to obtain this information in this study are different and thus our results are not directly comparable. However, based on the large proportion of late-stage diagnoses in Mexico, as well as the clinical experience in the day-to-day practice of oncologists that frequently encounter patients after long diagnostic delays, it seems that the participants are probably underestimating the delay. The important role that these physicians have as primary contacts for patients seeking care cannot be stressed enough because their initial actions or inactions can ultimately contribute to delays in BC diagnosis. These physicians have to be aware of the actual delays BC patients face and incentivized to provide adequate referrals and workup to overcome these barriers to BC care.

To reduce delays in BC care, establishing fast and accurate referral pathways has proved to be an effective strategy. In the United Kingdom, a retrospective study reported a decrease in the average interval from symptom onset to diagnosis to 26 days after the implementation of referral guidelines for the suspicion of various types of cancer, including BC16. Similar data is available from Denmark, where, after the implementation of referral pathways for cancer patients, an average reduction of 17 days was achieved in the interval between the first office visit and cancer diagnosis17. Notably, in the present study a remarkable proportion of healthcare providers were unaware of the existence of referral pathways for BC care in their institutions (36% in the public and 67% private sector). This study also identified a significant association between the lack of knowledge about referral pathways and a perceived prolonged time from symptom onset to treatment initiation. Hence, this lack of awareness may be a possible contributor to delays in BC care.

The lack of knowledge about referral pathways for BC care was further supported by the fact that there was no common physician action plan for the diagnosis or referral to specialty care in case of suspected or confirmed BC, as the participants did not uniformly order the same diagnostic tests and made referrals to different specialists. Notably, a Swedish study found that the lack of clarity of referral pathways for cancer care was perceived as a major limitation to effectively implement them18. In Mexico, despite the existence of national guidelines for BC care, these are vague in relation to intervals to diagnosis and treatment, and referral pathways are not specified in the event of a suspected or confirmed BC diagnosis19,20. Having standardized clear and universally adopted referral pathways can be a key intervention to reduce delays in BC care in the country.

In this study, physicians were also questioned about the perceived causes of delays in care. Participants reported patient-related factors (fear, apathy, ignorance, financial limitations, and transportation) as a major cause of delay. Moreover, this study highlights the limitations of the public healthcare system. In accordance with previous studies in Mexico and Latin America, lack of infrastructure, insufficient human resources, and saturated health services were identified as major barriers to care21-23. Identifying these barriers has allowed the development of different strategies aimed at reducing delays in care16,17,24-32. Among these initiatives, we highlight the development of national guidelines, the creation of rapid reference pathways for patients with symptoms suggestive of BC, the implementation of patient navigation programs, and the adoption of telemedicine16,17,24-32. Particularly in Mexico, the Alerta Rosa program was created as a strategy to improve patient navigation and prioritization27,28. The results after 2 years of operation demonstrated a reduction in the interval to treatment initiation of 33 days. This achievement led to the recognition of Alerta Rosa by the World Health Organization as an effective intervention to enhance early BC diagnosis. This highlights the need to implement, assess and universally adopt strategies that have proved to be effective at a national level.

The results of this study do not represent the national perception uniformly, several limitations should be considered. First, the nature of the questionnaire limits an in-depth analysis of common clinical perceptions and practices. Convenience sampling was used to gather the data and the survey was distributed through social media platforms over a span of a week. Also, digital platform literacy is another limitation of our study distribution method potentially excluding older participants and less digitally inclined physicians. Furthermore, it is not possible to guarantee that all the participants were healthcare providers, even though the survey was exclusively aimed at this population. This study is prone to other types of bias due to the sampling method employed such as self-selection bias, and response and nonresponse biases. Finally, although the survey was promoted throughout Mexico, the results cannot be generalized to the entire country. Despite these limitations, this work has some important strengths. This is the first study in Mexico that evaluates the perception of healthcare providers on this topic. It also highlights the need for a widely adopted referral pathway for BC diagnosis and treatment in Mexico.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the physicians interviewed in this study do not follow a common referral pathway for BC diagnosis or specialty care. This information provides a broader understanding of the needs that must be addressed for the development of new regulations for BC care in the country. Some of the strategies that could reduce delays in BC care and promote the use of standardized referral pathways are:

− Sensitize medical professionals about the actual delays patients face.

− Infrastructure development.

− Adequate allocation of resources.

− Prioritizing the care of symptomatic patients.

− Improving patient navigation.

− Establishing effective and specific referral pathways.

− Implementing measurement, monitoring and feedback systems.

− Promoting universal adoption among all healthcare providers.

The development and implementation of national strategies aimed at strengthening the healthcare system and decreasing delays in BC care must become a priority to guarantee timely diagnosis and quality care for all BC patients in Mexico.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)