Introduction

Mutations in BRCA1/BRCA2 genes and other non-BRCA1/2 genes cause about 5-15% of breast cancer (BC) and ovarian cancer (OC)1,2. Molecular studies to determine if mutations exist in these genes must be accompanied by a cancer genetic counseling (CGC). The CGC which helps participants to understand and adapt to the medical, psychological, and family implications derived from the risk of developing cancer3. As part of the CGC, it is important to inform the participants about preventive measures, the probability of transmitting the mutation and the consequent risk to their descendants, as well as to support them in making informed decisions. In addition, CGC coordinates the communication between several professionals to provide comprehensive care to the participants and their families4, including emotional support by a psychologist4,5. Emotional reactions are diverse in CGC participants: stress, fear, worries, anger, frustration, anxiety, guilt, loneliness6,7, and hostility8.

In Guadalajara, Mexico, the CGC service (CGCS) exists since 2012. This CGCS is led by the Universidad de Guadalajara, in collaboration with the Instituto Jalisciense de Cancerología, the Hospital Civil de Guadalajara, and City of Hope, Medical Cancer Center from the United States. The Psychological Care Program (PCP) and CGCS have been designed for attend the genetic and psychosocial needs detected in the participants of the involved hospitals. Approval has been obtained to carry out genetic studies and research by this institution.

The aim of this paper is to describe the developmental process and characteristics of the PCP, which is part of the CGCS in Guadalajara, Mexico, for participants with high risk of BC and OC.

Theoretical framework

The psychological management performed during the CGCS is framed within health psychology. It focuses on the emotional care of patients with high risk for hereditary cancer and their families. The health psychology includes promotion of healthy behaviors, family communication, and decision-making strategies9.

Cognitive behavioral therapy was selected for patient management because there is a vast evidence of its effectiveness in BC patients10 and indicates a clear relationship between thoughts, emotions, and behaviors11. Some of the conditions that may be addressed under this approach are anxiety, depression12, dysfunctional thinking, stigmatization13, and stress14.

Strategies of third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies are also used, particularly acceptance and commitment therapy and mindfulness. The acceptance and commitment therapy is considered rigorously behavioral15 and has been implemented within the context of genetic counseling16.

Finally, the transtheoretical model is one of the most frequently used for behavior change and argues that individuals go through stages of change which are made up of different processes that occur within each stage. Intervention strategies are suggested according to each stage of change17.

Development of PCP in the CGC

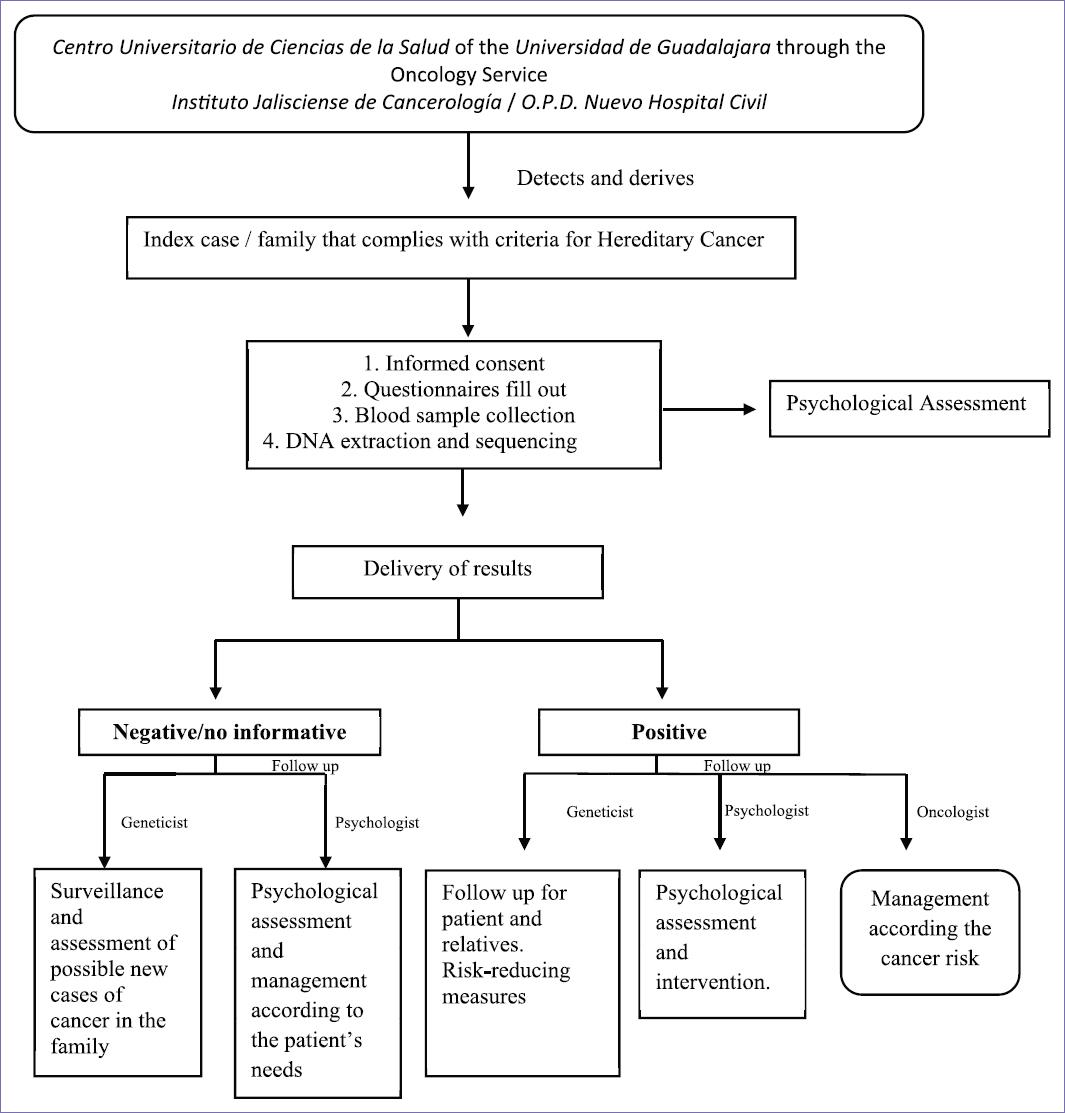

The PCP was implemented considering several process stages (Fig. 1).

The first step began with a collaboration between the Centro Universitario de Ciencias de la Salud of the Universidad de Guadalajara and several institutions which included the Hospital Civil de Guadalajara, Instituto Jalisciense de Cancerología, Hospital de Especialidades, and the Hospital de Ginecoobstetricia del Centro Medico Nacional de Occidente. This collaboration began in 2006 thanks to the ELLA Binational BC Study18. In 2012, the collaboration with City of Hope Medical Center allowed for professional training in the CGC and for the implementation of the CGCS19 which is the first service of CGC in Western Mexico9. The vision is not only to provide integral, high-quality preventive and medical services but also to provide psychological support. The CGCS team is composed of a geneticist, oncologists, plastic surgeons, nurses, nutritionists, and psychologists (Fig. 2).

A second step included multiple trainings. Oncologists, geneticists, psychologists, and nutritionists provided the trainings in CGC, regarding all aspects of hereditary and familial cancer. This included the molecular basis, clinical phenotypes, and models for genetic risk, prophylactics, as well as nutritional and psychological implications. Moreover, trainings in psycho-oncology were provided with the support of the Susan G. Komen Foundation through the patient navigation program. In addition, the psychologists visited other genetic counseling services in Madrid and Barcelona, Spain, to receive training in psychological management of CGC patients.

As a third step, to establish goals and support the decision-making process for an ideal PCP, an exhaustive and systematic literature review was carried out. On the one hand, several articles and manuals related to the management of CGC patients were consulted, and on the other, scales and intervention strategies were analyzed and selected20,21. This review led to the definition of the PCP goals and guided the decision-making process regarding the pilot test and future implementations.

The pilot test was the fourth step of the development process. Patients were assessed face to face with an initial version of a semi-structured interview created by the program psychologist and psychosocial scales taken from other CGCSs such as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)12,22,23 and the Impact of Event Scale12,23.

Based on the pilot test, the fifth step consisted in the definition of scales according to their reliability and utility in CGCS patients. Furthermore, a new scale was created and validated to detect health-risk behaviors24 and the semi-structured interview was improved to detect psychosocial issues in Mexican population25. Intervention and follow-up strategies were implemented and are described below. Due to the high demand for the CGCS, a cooperation with both the patient navigation program26 and psycho-oncology services of hospitals was necessary, to assist as many participants as possible. They provided psychological treatment or referred to another service if they considered it appropriate.

Finally, to increase the number of patients, the sixth step consisted in searching for financial support. In 2016, the CGCS was supported by Cruzada Avon. Besides, the program is in the process of consolidation. This involves increasing the professionals trained in CGC, improving the infrastructure, increasing the areas to treat patients and their relatives, and promoting of the program.

Goals of the PCP

In CGCS, the psychologist has a key role in the whole process by detecting and treating psychological variables that may interfere in fulfilling medical recommendations related to prevention and health. Figure 3 shows the psychological attention provided in the CGCS.

The general goals of the PCP are: (1) to assess the psychological state, (2) to offer emotional and decision-making support, and (3) to improve health behavior of CGC participants.

Goal 1: to assess the psychological state

To accomplish the first goal, validated scales such as the HADS27 and the Multidimensional Impact of Cancer Risk Assessment28 are used. The HADS evaluates cognitive and affective aspects of anxiety and depression and assess three dimensions, according to the level of severity: normal, limit and morbidity. In addition, as an essential part of the assessment, an instrument was validated to evaluate health behaviors in people with high risk of cancer based on the transtheoretical model24. Finally, a semi-structured interview regarding issues such as family, social support, psychological background, lifestyle, and cancer perception was created25.

The assessment is applied in a private room of the Instituto Jalisciense de Cancerología or the Universidad de Guadalajara in three distinctive moments: (1) prior to the genetic testing, during the genetic consultation, to determine the appropriateness of the testing, (2) after the delivery of results of the genetic test (ranged from 1 week to 1 month), to assess the psychological consequences of the results, and, (3) during follow-up, to evaluate any residual psychological issues and their satisfaction with their own health decision-making. The follow-up with patients who received genetic results is carried out face to face or by telephone.

If issues not related to genetic counseling are detected, they are referred to the psycho-oncology service of the Instituto Jalisciense de Cancerología (in patients from these hospital) or to the patient navigation program (previously described), which offer psychotherapeutic follow-up.

Goals 2 and 3: to offer emotional and decision-making support and to improve health behavior of CGC participants

To achieve the second goal, intervention differs for participants with and without genetic mutation since each group has different specific objectives (Fig. 3) which were identified according to the participants psychosocial assessment and general recommendations of National Comprehensive Cancer Network29.

Decision making aids related to communication of test results or prophylactic surgery have been widely reported for carriers30,31 as well as psycho-education32, reduction of emotional impact33 and promotion of healthy lifestyles34. For participants with non-informative genetic results, psychoeducational interventions regarding cancer and its risk have been reported35 as well as health behaviors promotion12.

Techniques implemented

For intervention, techniques are based on cognitive behavioral theory14,36,37, third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies16,38, and the transtheoretical model39 (Table 1). The number of sessions and the techniques implemented in each patient varies according to the needs presented. The duration of each session is approximately of 1 h.

Table 1 Techniques used within the psychology service

| Specific objectives | Techniques | Theoretical framework | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants with genetic mutation | To decrease psychological affections | Acceptance and normalization of emotions related to

the genetic results. Relaxation techniques Mindfulness techniques |

Acceptance and commitment theory Cognitive behavioral theory Mindfulness |

| To clarify erroneous patient information | Interview and psychoeducation | ||

| To help in decision-making (prophylactic and preventives alternatives, communication of result with family) | Decisional balance according to personal values | Acceptance and commitment theory | |

| To promote healthy behaviors. | Techniques for modifying health risk behaviors (i.e., contingencies management, psychoeducation, reinforcement, activity planning, and social support) | Transtheoretical model | |

| Participants without mutation | To clarify erroneous patient information. | Interview and psychoeducation | |

| To promote healthy behaviors. | Techniques for modifying health risk behaviors | Transtheoretical model | |

| To implement psychoeducation about cancer and its risk factors. | Psychoeducation |

Characteristics of the participants

More than 500 participants were treated in the CGCS from 2012 to 2019. The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants evaluated in the PCP are shown in table 2. The PCP attended 195 participants because they agreed to attend. All the participants took the genetic test. The follow-up was carried in 25% (n = 49) of all the participants. It is worth to mention that this follow-up was focused on patients whose results were positive for genetic mutation, achieving up to 75% corresponding to 18 of 24 positive cases. The sessions with that patients range from 4 to 7. Some patients with genetic mutation did not receive follow-up due to decline to participate, were uncontactable or they died.

Table 2 Sociodemographic characteristics of participants

| Age | M ± SD |

|---|---|

| 45.7 ± 10.28 | |

| Marital status | n (%) |

| Married/having a steady partner | 125 (64.2) |

| Divorced/widowed | 28 (15) |

| Single | 40 (21) |

| Education level | |

| Illiterate | 2 (1) |

| Middle* | 121 (62) |

| High* | 69 (35) |

| Employment status | |

| Employed | 78 (40) |

| Not employed | 114 (58) |

| Mutation status | |

| Positive | 24 (12) |

| Negative | 109 (56) |

| Not known | 62 (32) |

*Middle: elementary school, middle school, high school; High: college and postgraduate degree.

To some patients with non-informative results, a session for psychological assessment was provided. The main criteria for the follow-up of the non-informative patients were accept to participate.

Based on initial evaluation, the anxiety symptoms were found in 33% of the participants and depression in 19% (Table 3). Recently, results were published and showed that recurrent anxiety and depression are correlated with recurrent worries, grief, and sleep problems25. Regarding health behaviors, we found that the insufficient physical activity was the main risk behavior in the participants (Table 3).

Table 3 Results of the scales used

| Normal, n (%) | Borderline ,n (%) | Morbidity ,n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HADS* | Anxiety | 107 (66.4) | 21 (13) | 33 (20.4) |

| Depression | 129 (80) | 18 (11.1) | 14 (8.6) | |

| MICRA* | Distress | Uncertainty | Positive experiences | |

| m (SD) | m (SD) | m (SD) | ||

| 7.6 (8.3) | 11 (10.8) | 5 (6.4) | ||

| HBSCQ* | With risk behavior | Without risk behavior | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Tobacco smoking | 9 (7) | 115 (93) | ||

| Alcohol drinking | 6 (5) | 118 (95) | ||

| Physical activity | 58 (48) | 64 (52) | ||

| Use of mammography and/or ultrasound | 7 (6) | 112 (94) | ||

*HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; MICRA: Multidimensional Impact of Cancer Risk Assessment; HBSCQ: Health Behavior and Stages of Change Questionnaire.

Finally, other recently reported results show that uncertainty is very common in positive mutation carriers as well as anxiety. The main findings included that the personal values and the emotional impact of carriers are related to their decision-making. This decision-making was mainly focused on prophylactic surgeries. Some of the perceived benefits of this procedure were the risk reduction and calmness40.

Discussion

Psychosocial management in CGC has been extensively studied9,12,20,40-42. However, emotional support is often not provided by experts in psycho-oncology. Instead, other health professionals such as the genetic counselor or geneticist provided it. They evaluate, detect, and try to inform about psychosocial aspects associated with CGC, and they referral to psychology or psychiatry services in cases they deem necessary20,42-47. Nevertheless, many psychologists or psychiatrists do not know the clinical and emotional implications of CGC of the patients derived.

Other authors report psychosocial interventions with CGC population, but they did not clarify whether such interventions were part of the standard care of CGCSs or they were an independent service14,16,30. In relation to these kinds of psychosocial managements, Bensend (2013) found negative long-term consequences in participants of CGC who had received the service by non-experts in this area. It is important that CGCSs and all professionals involved, including psychologists, are adequately trained to attend participants of CGC.

Finally, there are few works (mainly clinical guidelines) by Ibero-American countries42,48,49, which evidence and describe the work of the psychologist within CGCSs. The PCP tries to encourage the inclusion of the psycho-oncologist into the multidisciplinary work of CGCSs. These professionals must have medical knowledge about hereditary syndromes. Furthermore, they must interact daily and actively with all members of the service48,49. Psychological support can help participants to understand the significance of their genetic risk not only in the social and psychological realm but also in family dynamics50. Moreover, the care of psychological issues is critical in CGC, resulting in an optimal quality of life for individuals and their families21.

Final considerations and next steps

Some of the strengths that support the PCP are as follows: (1) the cooperation between hospitals and the university; (2) the multidisciplinary interaction during the CGC process; (3) the creation of instruments, such as semi-structured interviews and the health-related behaviors questionnaire, which are tailored to the participants and to the health-care system specific needs; and (4) the training to CGC psychologists in the hereditary cancer and the clinical management of individuals with high risk for cancer. In addition, other implications are the cooperation of complementary services, the healthy lifestyles promotion among participants with and without genetic mutation, and follow-up (face to face and telephone) for monitoring the psychological state of patients.

Next steps for improve the PCP are: to increase professionals with training in CGC, improve the CGC infrastructure, promote the PCP to increase the number of patients, obtain more national and international grants, extend psychological attention to family members, standardize and certify the program, and evaluate the impact of the program.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)