Introduction

Small bowel bleeding (SBB) is a rare entity, accounting for ~5-10% of all gastrointestinal bleeding cases1. Causes of SBB in < 40 years are inflammatory bowel disease, Dieulafoy’s lesion, neoplasms, Meckel’s diverticulum, and polyps. Gastrointestinal tract bleeding in patients with disseminated histoplasmosis and gastrointestinal involvement is unusual. The exact incidence of gastrointestinal histoplasmosis (GIH) is unknown because most patients remain asymptomatic2, only 3-12% of patients show symptoms3, it is reported in 70% of autopsies in immunosuppressed patients (HIV and transplant recipients)2 and in immunocompetent hosts in only 0.05% of cases4. Histoplasmosis is also known as Darling’s disease (1906), cave fever, or abandoned mine fever5. The etiological agent is the dimorphic fungus Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum, the mycelial or saprophytic infecting form, found in bat or bird excreta6. It is considered the most frequent deep mycosis in North America and the second most frequent in South America5, with microfoci in East United States, South Europe, Africa, and Southeast Asia7. In Mexico, it is the most important systemic mycosis, according to the reports of outbreaks during 1988-1994, it is endemic throughout the country, predominantly in Morelos, Guerrero, Veracruz8, and Oaxaca6. We present a clinical case of an immunocompetent patient with massive SBB and Grade IV hypovolemic shock associated with systemic histoplasmosis, treated with intestinal resection and amphotericin B.

Clinical case

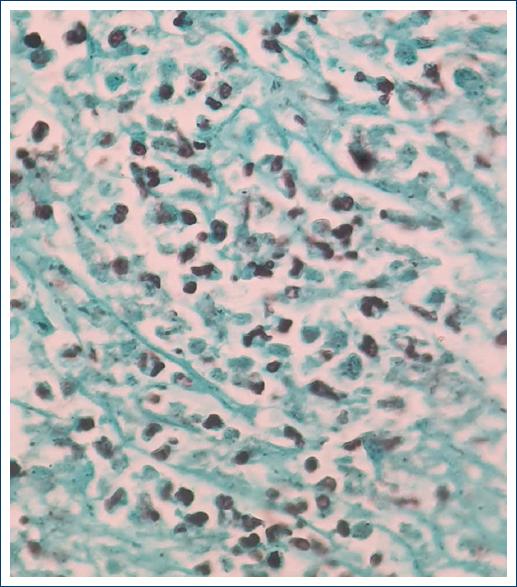

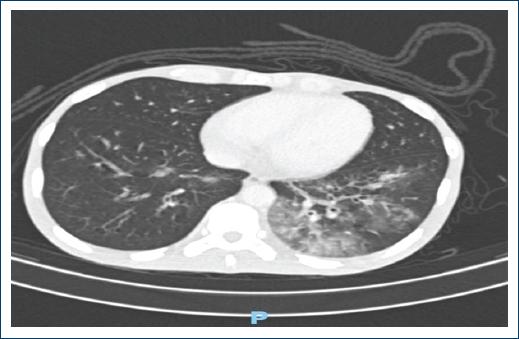

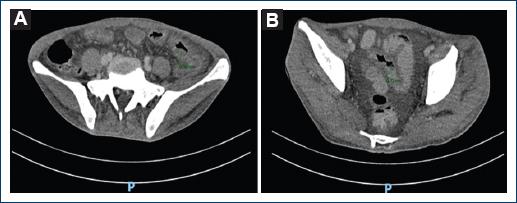

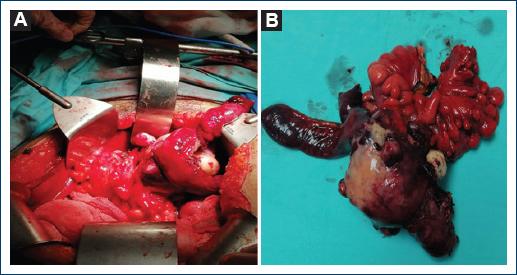

A 29-year-old male patient, native and resident of Oaxaca, farmer and rubbish collector, with a history of alcohol and methamphetamine abuse, starts clinical condition of 6 months with colicky abdominal pain in hypogastrium, intensity 7/10 in VAS, evening fever, weight loss of 20 kg in 2 months, diarrhea and constipation, choluria, and non-productive cough. He was admitted to the emergency department for abdominal pain, respiratory distress, altered state of consciousness and hemodynamic instability, heart rate 120 bpm, respiratory rate 22 rpm, mean arterial pressure 60 mmHg, temperature 38.9°C, rales in the left lower lobe, painful abdomen in the left iliac fossa, and hepatomegaly. Laboratory studies were requested, reporting Grade I anemia, hypoalbuminemia, moderate hyponatremia, prolonged coagulation times, blood chemistry and viral panel without alterations, and discrete elevation of fibrinogen (Table 1). Computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest and abdomen (Figs. 1-2) with images suggestive of multisegmental pneumonia, hepatomegaly, mesenteric and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy, ascites, concentric thickening 12 mm of the wall of the descending colon and sigmoid colon, and endoscopy without alterations. Colonoscopy reported erosions in the mucosa at the proximal sigmoid level, without passage to the distal ileum due to ileocecal valve stenosis. A biopsy was taken that reported moderate chronic erosive colitis, not active. Four days later, he presented with acute abdomen accompanied by hematemesis and hematochezia leading to hypovolemic shock Grade IV, hemoglobin 6.1 mg/dl, platelets 52,000 mg/dl, TP 29.1 s, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura 49 s, and INR 2.2 s. The patient underwent emergency surgery and was found to have an ileum-dependent tumor measuring 8 × 5 × 4 cm (Fig. 3), 1 m from the ileocecal valve. It involved the parietal peritoneum and sigmoid colon, with abundant lymph nodes in the root of the mesentery larger than 1 cm in diameter. The tumor was resected en bloc including 60 cm of terminal ileum and 30 cm of sigmoid colon with a 60 mm GIA linear stapler, ileostomy of the proximal end, closure of the distal end of the remaining 70 cm ileum and end-to-end anastomosis of the descending colon, and the remaining sigmoid colon. The histopathological report of the surgical specimen showed chronic inflammation, deep ulceration of the mucosa with abundant intracellular microorganisms in yeast-like macrophages positive for GROCOTT, and periodic acid–Schiff staining (Figs. 4-5). The diagnosis of intestinal Histoplasmosis was established and treatment was started with liposomal Amphotericin B at a dose of 5mg / kg / day. One week after treatment, he presented cardiac arrhythmia and sudden death.

Table 1 Values reported in laboratory studies on patient admission

| Blood biometry | |

| Leukocytes | 9.3 × 103/mm3 |

| Neutrophils | 7.3 × 103/mm3 |

| Hemoglobin | 10 g/dl |

| Platelets | 221 × 105/mm3 |

| Blood chemistry | |

| Glucose | 81 mg/dl |

| Urea | 8.5 mg/dl |

| BUN | 1.2 mg/dl |

| Creatinine | 0.5 mg/dl |

| Uric acid | 1.2 mg/dl |

| Coagulation times | |

| TP | 21.2 seg |

| TTPa | 84 seg |

| INR | 1.5 seg |

| Fibrinogen | 448 mg/dl |

| Special tests | |

| HIV-1 and HIV-2 | Non-reactive |

| TORCH profile | Non-reactive |

| Guayaco | Positive |

| Tumor markers | |

| Ca 19-9 | 186.4 UI/L |

| CAE | 1.58 ng/ml |

| Alpha-fetoprotein | 1.94 ng/dl. |

Figure 1 Plain and contrasted tomography of the thorax with evidence of ground-glass opacity, an image suggestive of the left multisegmental pneumonia.

Figure 2 A: simple and contrasted tomography of the abdomen is evident in the descending colon and sigmoid colon. B: thickening of the colon wall with a maximum diameter of 12 mm.

Figure 3 A: 8 × 5 × 4 cm tumor involving parietal peritoneum at the level of the left deep inguinal ring dependent on the distal ileum. B: surgical specimen of ileum-dependent tumor, which was resected with a margin of 10 cm of lesion.

Discussion

Histoplasma infection starts with inhalation of aerosolized microspores of microconidia and hyphae6, in the alveolar sac, they are phagocytosed by macrophages, the conidia develop into yeast5 at 35-37°C4 and reach the macrophage interior to multiply5 until the T-cell response. Primary Histoplasma infection is asymptomatic and remains dormant4, < 5% of exposed individuals develop symptoms. Cell-mediated immunity favors hematogenous spread of the fungus especially to the reticuloendothelial system3. The immune response blocks its progression by forming calcified granulomas in the affected organs5, and if the T-cell response is inadequate, it reactivates4. The most susceptible are patients with AIDS, HTLV-1 infection, hepatitis C infection, renal failure, glucocorticosteroid use and biological agents9, as well as methamphetamine use10. Disseminated disease in immunocompetent patients is found in < 0.05%4 and only nine cases of GIH in immunocompetent patients have been reported2, probably due to an unknown defect in cell-mediated immunity4. Disseminated histoplasmosis is rare and lesions in the gastrointestinal tract are infrequent, manifesting as esophageal involvement in mediastinal adenitis, mediastinal fibrosis with esophageal involvement, and disseminated histoplasmosis with gastrointestinal involvement. The latter is frequent in men in the fifth decade of life4 and can occur at any site of the gastrointestinal tract9, the terminal ileum being the most common site because of its rich lymphatic system, manifesting with ulcers11, as in the reported case. About 30-50% of patients with GIH report non-specific abdominal pain, fever, weight loss or diarrhoea2, ulcers, polyps, strictures, and perforations may be present5, complications are rare such as bleeding and protein loss due to enteropathy and hypogammaglobulinaemia9. Bleeding is more common in AIDS patients than in immunocompetent patients (18% vs. 9%)3, and three renal transplant patients with intestinal perforation have been reported12, patients with hemorrhage present hematochezia or melena, depending on site and intensity13. Immunosuppressed patients may begin with obstruction by annular, constricting lesions, or large polypoid masses, from the rectum to the cecum, resembling appendicitis, malignant neoplasia, or inflammatory bowel disease3. The clinical case reported is a male patient in his third decade of life, a farmer and rubbish collector, which predisposes him to contact with the infective forms of Histoplasma. Although no apparent cause of immunocompromise was documented, the patient had risk factors that predisposed him to a decrease in the immune response, the consumption of methamphetamines, according to Potula et al., demonstrated that stimulants such as methamphetamine (METH) exert immunosuppressive effects on the host innate and adaptive immune systems, because METH can limit T-cell proliferation by exerting a prolonged G1/S phase in the cell cycle and a significant decrease in the expression of cyclin E, CDK2, and transcription factor E2F110. Similarly, hypoalbuminemia and alcohol consumption correlate with poor nutritional status of the patient. In a retrospective study of pediatric patients diagnosed with histoplasmosis, malnutrition was identified as the most important risk factor because it is considered the leading cause of secondary immunodeficiency in the world, decreasing the host immune response, including cell-mediated immunity14. The diagnosis of GIH, either by exclusion or as a finding, its differential diagnosis includes chronic inflammatory processes such as Crohn’s disease, cancer, and intestinal tuberculosis. Laboratory findings may be non-specific, although they reflect signs of bone marrow involvement (anemia, leukopenia, and plateletopenia) and liver function5. In cases of suspected histoplasmosis, direct microscopic examination, culture, antigen detection, and serological tests for antibodies are used for diagnosis3. Multiphasic CT or CTA can detect bleeding of 0.3 ml/min; however, the patient must be actively bleeding at the time of the study, findings of blood within the lumen or sentinel clot help localize subtle or absent bleeding1. GIH images are bowel wall thickening, large masses, signs of small bowel obstruction, and free peritoneal air, while findings of disseminated histoplasmosis are hepatosplenomegaly, pulmonary infiltrates, and generalized intra-abdominal lymphadenopathy3. In the clinical case, the patient began with non-specific gastrointestinal symptoms and pneumonia. The initial CTA did not identify an active bleeding site. However, the data found were multisegmental pneumonia, hepatomegaly, mesenteric adenopathies, and thickening of the wall of the descending colon. The gastrointestinal tract bleeding presented as fecal occult blood, which progressed to Grade IV hypovolemic shock. Prolonged coagulation times and decreased platelet levels were the factors associated with bleeding, at the expense of a slight elevation of fibrinogen on admission, probably because the average half-life of fibrinogen is 100 h, the patient presented bleeding data until the 4th day of inpatient stay. Direct visualization and biopsy for culture and pathology are essential for the diagnosis of both gastrointestinal tract bleeding and intestinal histoplasmosis. The algorithm established by the American College of Gastroenterology divides SBB into patients with stable or unstable hemodynamic status; the former are candidates for endoscopy, and if this is not satisfactory, an auxiliary method is used; in unstable patients, resuscitation measures are initiated, followed by imaging, endoscopic, surgical, or combined studies to demonstrate the site of bleeding1. If no bleeding site is found in the first endoscopy, capsule endoscopy is used to identify SBB, an unrecognized lesion in the stomach or colon13. However, few centers in Spain have this tool, so in the event of a second endoscopic examination, push enteroscopy is an ideal procedure; another tool is intraoperative enteroscopy (IOE), which involves the evaluation of the small intestine during laparotomy1. Lesions found in GIH include single or continuous superficial mucosal ulcers, deep bleeding ulcers with or without frank perforations, areas of friable and mass containing necrosis, and obstructions due to circumferential exophytic thickening9. Diffuse ulceration was observed in 85.7% of cases with AIDS-related GIH4. In the patient reported in the clinical case, colonoscopy identified erosions at the level of the proximal sigma that stands out on surface staining and non-active moderate chronic erosive colitis. Transoperative findings included ileum-dependent tumor leading to significant bleeding and transoperative endoscopic findings of fibrin-covered lesions and areas of active subepithelial hemorrhage up to 20 cm of ileum. In the histopathological report of GIH, macrophages in the mucosa and submucosa show round eosinophilic organisms, 1-4 mm in size with a transparent halo around them4. Four different pathological forms have been recognised9 (Table 2). In the documented case, the pathological form presented was type IV due to localized thickening at the level of the distal ileum involving the sigmoid segment.

Table 2 Pathological forms of gastrointestinal histoplasmosis

| I | Subclinical, microscopic clusters of macrophages in the lamina propria (LP) |

| II | Plaques and pseudopolyps caused by fungi contained in macrophages |

| III | Tissue necrosis and ulceration leading to abdominal pain, diarrhea, and bleeding |

| IV | Localized thickening with inflammation of the bowel, simulates cancer, or Crohn’s disease |

Histoplasmosis can be diagnosed by serum tests, complement fixation, radioimmunoassay, precipitation test, polymerase chain reaction, and microscopy. Grocott stained culture is the gold standard for diagnosis as it stains the capsule around the yeast forms4. However, it is not recommended as an initial study because it takes 4-6 weeks for the organism to grow4. The reported patient’s diagnosis was histopathological by Grocott staining 10 days after the surgical event.

Treatment of mild-to-moderate GIH is itraconazole 200 mg 3 times daily for 3 days and then twice daily for at least 12 months15. In severe cases, liposomal amphotericin B 3.0 mg/kg daily for 1-2 weeks, followed by oral itraconazole 200 mg 3 times daily for 3 days and continue 200 mg twice daily for at least 12 months. Treatment of SBB should be managed according to the algorithms for STD, massive bleeding associated with histoplasmosis has only been reported by Bruno et al., in a patient in association with cytomegalovirus and AIDS, finding a 2 × 2 cm tumor in the distal ileum16. Surgical treatment for SBB is usually considered as a last resort and is guided by IOE, whenever possible. Indications for emergency surgery include hemodynamic instability with active bleeding, persistent recurrent bleeding, or the need for transfusion of more than 6 units of red blood cell concentrate in 24 h with active bleeding17. When the location of the hemorrhage is known, segmental resection ensures recovery with a mortality rate of < 3-5% and a recurrence rate of 2-10%16.

Conclusion

Gastrointestinal tract bleeding of unknown origin associated with GIH is a very rare entity in immunocompetent patients, with nutritional status and methamphetamine use being predisposing risk factors for its activation. Due to its characteristics, a diagnosis of exclusion makes it necessary to rule out pathologies such as Crohn’s disease, UC, lymphoproliferative processes, and intestinal tuberculosis. Appropriate treatment leads to long-term survival, while untreated cases are almost fatal, especially when there is an association with gastrointestinal tract bleeding. Hence, joint treatment should be carried out and in the event of massive bleeding secondary to GIH, surgical resection should be considered if the site of bleeding is identified.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)