Introduction

Gastrointestinal endoscopy has changed constantly, from the beginning by Kussmaul in 1868 who performed the first gastroscopy. Today, the advance of endoscopes from fiber to high definition with magnification has made it possible to search for almost cellular changes in patients for conditions that will develop into gastrointestinal tumors, affecting the natural history of cancer1.

Advances in equipment and accessories are allowing for less invasive, curative, and palliative therapeutic procedures, thank to the joint work of anesthesiology-endoscopy, which has allowed for more complex and time-consuming procedures in advanced diseases. These conditions have led to the recognition of the need and value of the support of the anesthesiology service2.

The unique conditions of endoscopic procedures make it almost a subspecialty within anesthesiology. At present, in most hospitals, there is little or no rotation in the endoscopy service for residents during their academic training.

Anesthesiologists are used to having absolute control of the airway and are trained to adequately resolve any respiratory complications. They are used to perform anesthetic inductions in procedures where general anesthesia is required. However, in the area of endoscopy, they must find a balance between deep enough sedation to tolerate the passage of the endoscope and therapeutic maneuvers and avoid causing apnea and desaturation, with the consequent removal of the endoscope to ventilate the patient and resolve the complication.

The aim of this review is to raise awareness of the need for anesthesia and endoscopy teamwork to perform increasingly complex studies, as well as of the alternatives in case of high-volume centers to perform high-demand procedures without sedation.

In endoscopy departments, patients are assessed by both the endoscopist doctor and the anesthesiologist on the day of the procedure3. It is important to detect comorbidities (the most important of which are cardiac and respiratory conditions, overweight or obesity, craniofacial anomalies, and cancer) which help to foresee potential complications and thus determine the type of anesthetic procedure required4.

Anesthetic protocol in the endoscopy area

Part of the indications given to the patient for an endoscopic study is fasting; the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) recommendations are 2 h for clear liquids, 4 h for light meals, and 8 h for large meals5. In the case of colonic preparation, regardless of the schedule, there is little or no gastric residue if the fasting times are respected6.

The indication for the study is of utmost importance as the presence of tumors, stenosis, or hemorrhage increases the risk of bronchoaspiration. In these cases, it is advisable to use local anesthesia or minimal sedation, keep the patient semi-sitting, and perform a quick initial check to see the gastric or esophageal contents and aspirate as much as possible to determine whether to continue with sedation or require general anesthesia to protect the airway.

Minimal monitoring in patients requiring sedation includes non-invasive blood pressure, pulse oximetry, 3-lead electrocardiogram, and in case of CO2 insufflation, capnograph7.

Sedation options

Most patients presenting for routine endoscopy are healthy and have few comorbidities. Some will tolerate the procedure with local anesthesia alone, but most require light sedation, with an opioid and a benzodiazepine. The benefits of this sedation, especially in upper endoscopy, are amnesia, comfort, and prevention of nausea, choking sensation, and arching, conferring greater safety in the performance of the endoscopic procedure8.

The depth of sedation depends on the type of procedure to be performed and the timing of the procedure. There are situations in which the stimulus is more intense, especially if therapeutic procedures are performed (dilatation, endoscopic loops, and technical difficulties), the medication adjustments must be made quickly and carefully to avoid deepening the sedation too much, resulting in respiratory depression and desaturation, leading to interruption of the procedure to rescue the patient.

It is important to note that sedation is a continuum9, each patient responds differently to medications and may progress to a deeper level of sedation than planned and even to the general anesthesia phase at the usual doses. The challenge is even greater because the presence of comorbidities, previous medications, age, and history of substance abuse, all play a role in the response to anesthetic drugs10. More advanced endoscopic procedures are performed under deep sedation or general anesthesia to avoid interruptions of the procedure due to respiratory disturbance, allowing for shorter procedure times and fewer adverse effects.

Drugs used in anesthetic procedures in endoscopy should share some essential characteristics: rapid onset of action, rapid termination of effect, easy dose adjustment, no cardiovascular disturbances, and no increased risk of post-operative nausea and vomiting.

The drugs are used in combination, the most common being midazolam/fentanyl/propofol. When combined, the initial and total doses of each are significantly decreased, the doses described below (Table 1) are those used in this scenario.

Table 1 Commonly used drugs in sedation for endoscopic procedures

| Drug | Type | Dose | Initial effect | Duration of effect | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Midazolam | Anxiolytic Benzodiazepine |

Initial 0.5-2 mg (bolus), 0.5-1 mg (repeat in boluses every 2 min) | 2-5 min | 15.8 min | Complete removal in 6 h |

| Fentanyl | Analgesic Opioid |

Initial 2 mcg/kg 1-1-5 mcg/kg (obese) 0.5 mcg/kg (repeat in boluses every 2 min) | 2-5 min | 45-60 min | --- |

| Sufentanil | Analgesic Opioid |

Initial 0.1-0.2 mcg/kg 0.05 mcg/kg (boluses every 3-4 min) | 4-6 min | 40-50 min | 10 times more potent than fentanyl |

| Remifentanil | Analgesic Opioid |

Continuous infusion 0.04 - 0-16 mcg/kg/min | < 90 sec | 6-10 min | Opioid ideal for use in endoscopy |

| Propofol | Hypnotic GABA agonist |

Boluses: initial 0.3-0.4 mg/kg, supplement with

0.1-0.2 mg/kg every 40-60 sec. At study initiation, boluses o 0.2-0.3 mg/kg every 2-3 min0.2-0.3 mg/kg every 2-3 min Infusion: 60-150 mcg/kg/min adjusting dose |

30-45 sec | 4-8 min | Most commonly used agent in endoscopy |

| Ketamine | NMDA agonist | 0.3-0.5 mg/kg in adults | --- | --- | Facilitates the passage through the cricopharyngeal muscle |

| Dexmedetomidine | Alpha 2 agonist Hypnotic |

0.2-0.5 mcg/kg, 10 min bolus | --- | --- | Respiratory depression is much less than with the other medicines |

kg: kilogram; mcg: microgram; mg: milligram; min: minute; sec: second.

Some considerations and characteristics in the use of these drugs are described below:

Midazolam

Not recommended for use in patients over 60-65 years of age due to an increased incidence of neurological adverse effects (delirium), and some studies have shown that the incidence of hiccups during studies increases when using more than 2 mg11. Not recommended for use in patients with liver or kidney failure.

Propofol

The most common drug for deep sedation or general anesthesia. It has dose-dependent hypotensive properties and causes respiratory depression. Benefits include antiemetic and antipruritic properties, interferes with swallowing and functional integrity of the upper airway. Synergizes with opioids and benzodiazepines for respiratory adverse effects. Dosage is lower in elderly, hypovolemic patients and in the presence of comorbidities.

Ketamine

It produces dissociative anesthesia. It can be used as a single anesthetic, but adverse effects (hallucinations) limit it to use mainly in the pediatric population. Among its undesirable effects are drooling, which can make airway management difficult, so it is necessary to administer antisialogogues (atropine, 0.3-0.5 mg, or glycopyrrolate) to avoid it12.

Dexmedetomidine

It can produce bradycardia and hypotension as side effects, so it is beneficial in hypertensive patients or those with cardiovascular pathology. It is not widely used because residual sedation usually lasts longer, and this is a problem in outpatient procedures, delaying discharge from 30 min to 2 h.

The steps to be taken for sedation in an upper endoscopic procedure are to determine whether sedation or general anesthesia will be used. If it is the first option, the patient is admitted to the room, monitored, and a device is placed to administer supplementary oxygen (nasal prongs, nasal mask, or facemask with an endoscope opening). Then, the patient is placed in the left lateral decubitus position and medication is started with fentanyl (1.5-2 mcg/kg) and midazolam (1-2 mg IV). After 3-5 min, the mouthpiece is placed, at which time topical anesthesia (lidocaine) may or may not be administered. Ketamine (0.3 mg/kg) and atropine (0.3 to 0.5 mg) are then administered, and the infusion of propofol is started. At this point, it is very important to start slowly and adjust the infusion to low doses. The incidence of apnea is very high, especially for anesthesiologists unaccustomed to out-of-theater procedures, and is not always immediate.

The most difficult moment is the passage of the endoscope through the cricopharyngeal muscle. The most common problem is that at the beginning of the endoscopy the patient does not tolerate the passage and requires additional doses of medication. If these are not adequately titrated, the patient will tolerate the passage of the endoscope, but will also stop breathing, and after 30-90 s will present desaturation and will require rescue ventilation and a pause in the study to remove the endoscope.

Once the cricopharyngeal muscle is surpassed, the movements of the endoscope do not cause as much discomfort and generally do not require sudden adjustments of the medication, except at specific times (cutting, dilatation, and balloon use). It is of utmost importance to avoid overdosing if the patient is moving, as stress and the need to stop movement at these times may cause the dose to be excessive and lead to a respiratory emergency.

Communication with the endoscopy team as well as knowledge of the procedure to be performed is necessary to anticipate painful events (balloon inflation, passage of the endoscope through difficult areas, and excessive distension) and adjust the dosage accordingly.

In the case of lower endoscopy (colonoscopy), it has been observed that with shallower levels of sedation, the incidence of perforations decreases (by warning that excessive pressure is being applied and therefore stopping it in time)13.

In general, depending on the duration of the procedure, fentanyl boluses are repeated every 20-40 min, analgesics and/or antispasmodics may be added. Finally, once the procedure is completed, the infusion is stopped, secretions are aspirated and the patient is monitored until alertness is restored.

Airway adjuvants

During deeper phases of sedation, instruments are needed to provide adequate oxygen flow and airway protection, as even if spontaneous breathing is maintained, ventilation may be inadequate, especially in upper endoscopy.

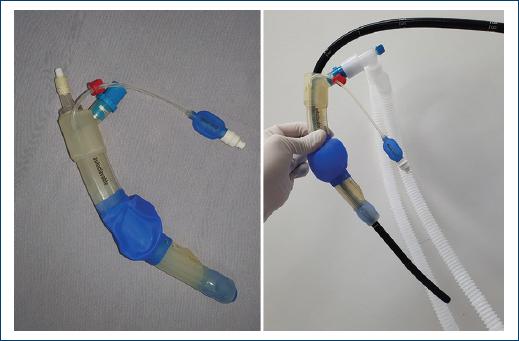

Maneuvers such as jaw traction, cervical extension, use of continuous positive airway pressure nasal masks, face masks with endoscope port, high-flow nasal prongs, and in some cases, either primary or rescue, airway sharing devices such as gastrolaryngeal tubes, and laryngeal mask airway Gastro mask are necessary14. Patient characteristics will determine the type of support (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 Laryngeal Mask (Medizintechnik GmbH) - airway device with a hole for endoscope insertion and a hole for ventilation.

Securing the airway should not be considered a failure of the anesthesiologist; intubation is the safest way to protect the airway should regurgitation occur. It may be necessary at any time, especially in long or complex procedures.

Some of the indications for intubation in endoscopy include emergency procedures, severe respiratory or cardiac comorbidities, morbid obesity, bowel obstruction, anatomical problems, duration of procedures (arbitrarily more than 60 min), complexity of the procedure, and drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts, use of double balloon, and use of large amounts of irrigation fluid, among the most important. The use of CO2 for distention requires monitoring of exhaled CO2 due to the large amount of absorption. Air embolism can occur, mainly during sphincterotomy and mucosectomy (Fig. 2).

Endoscopic scenario

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD)

EGD or upper endoscopy is a diagnostic and therapeutic tool that allows screening for different gastrointestinal neoplasms and treatment of different diseases, whether elective or emergency.

In general, endoscopic studies are performed with the aid of sedation by the anesthesiology service, however, in some high-volume centers; the study is only performed with topical anesthesia to suppress the gag reflex during the procedure. The most commonly used agents are lidocaine, benzocaine, and tetracaine, administered as an aerosol into the pharynx. Lidocaine, with an average dose of 60 mg (range 40-80 mg), can be administered by the endoscopist doctor or nurse, improving ease of endoscopy and patient tolerance15. Topical anesthetics have been associated with serious adverse effects such as aspiration, anaphylaxis, or methemoglobinemia. Therefore, they should be used with caution (Fig. 3).

In most patients who undergo an endoscopic study without sedation, the most common post-procedural side effects are odynophagia, abdominal distension, and colicky pain. These side effects in some patients make the study dreaded at subsequent endoscopic follow-up appointments, or even poorly recommended to their family and friends. The latter may result in a loss of follow-up in patients and thus increased risk of morbidity in them.

In addition, the endoscopist doctor who performs a procedure under local anesthesia knows that it is a quicker and in most cases, more targeted study, and in some cases, lesions may go unnoticed compared to a sedated study where a more thorough inspection can be performed.

Sedation in panendoscopy has several advantages, including causing amnesia of the procedure, which helps to forget the event and prevent anxiety about it, allowing subsequent studies to be performed. Moreover, in case of therapeutic procedures, these can be performed without haste and incomplete procedures can be avoided.

The adverse effects of sedation include respiratory depression, hypoxia, cardiovascular changes, and allergies, among others. Therefore, the anesthetic technique to be used on patients should be selected according to the urgency of the procedure and comorbidities16.

COLONOSCOPY

Colonoscopy has become a screening method of choice for colorectal cancer, as well as for the diagnosis and treatment of colonic diseases. It requires bowel preparation and sedation to perform a painless study, with less technical difficulty, and to reduce the patient's anxiety for subsequent follow-up studies.

Due to the aforementioned adverse effects of sedation, strategies have been tried to perform the study without anesthesia, keeping the patient pain free, and obtaining the same results in terms of study quality criteria according to the ASGE guidelines (cecal intubation and adenoma detection rate)17.

In 2018, Bashiri et al. in a Turkish study used music therapy as a strategy to reduce the dose of anesthetics, anxiety, and pain in patients who underwent colonoscopy with conscious and deep sedation. They observed that patients who underwent the procedure with music used lower doses of drugs, had less pain and anxiety after the procedure, compared with those who underwent the study without music18. This undoubtedly generates strategies to balance the benefits and risks of the use of sedation in this procedure, however, randomized clinical studies are required in our environment comparing this strategy with the conventional sedation developed in this review.

It may be difficult for a patient to desire a colonoscopy study without sedation, in some cases, its administration shows more risk than benefit, so the endoscopist doctor must seek strategies to perform the procedure with the least risk and most benefit.

Colonoscopy under water immersion is a strategy for performing the study, described since the 1980s, water helps to elongate the sigmoid, reduces the formation of loops, and does not generate distension, which helps to reduce the pain of colonoscopy, and requires minimal or no sedation19,20. Changes in position (turning the patient) during colonoscopy help to open up the angles of the colon and is a strategy to reduce pain during the study21.

Post-procedural complications

The incidence of complications in anesthetic (sedation) procedures in endoscopy is very low, Behrens reported an incidence of minor complications (0.3%), major complications (0.01%), and death (0.005%) among 368,206 electronic records. ASA class, type, and duration of procedure were significant factors for adverse outcomes22. In the United States, 53% of medicolegal cases closed were for adverse events associated with respiratory causes.

Reports that are more recent have found that the likelihood of adverse events was higher in patients whose care involved anesthesia personnel, and the incidence of bleeding and perforations was higher. While these findings may not indicate causality, it is more likely that the services of the anesthesia team are more sought after in patients with higher risks (sicker, more complex procedures, and older) and this is part of this higher incidence of adverse events.

Regarding the incidence of perforation and bleeding, the use of deeper planes of sedation implies a higher pain tolerance in patients, so there is not the necessary feedback in case the endoscope pressure or maneuvers cause excessive stress or damage to the gastrointestinal tract.

Conclusions

- The complexity of maintaining the patient by the anesthesiology service at an adequate level of sedation to perform the procedure means that the endoscopist doctor is increasingly requesting an experienced team as therapeutic procedures have greatly advanced.

- It is important for the anesthesiologist to have a detailed knowledge of the drugs for use in endoscopy to choose the appropriate option for the type of patient, helping to perform a successful and increasingly complex endoscopic procedure with the least risk to the patient.

- The safety of anesthesia in advanced therapeutic endoscopic procedures is undeniable, which is why you should communicate with the anesthesiology team about the procedure plan to match it with the anesthetic plan that leads to joint success in patient care.

- It is important to know different strategies to perform the procedure without sedation, in case, the patient's conditions do not allow it when their anesthetic risk is greater than the benefit of the procedure, however, the study will change the course of their disease or help in therapeutic decisions that impact on morbidity and mortality.

- This review was written to give an overview of the importance of multidisciplinary work in patient care in the area of endoscopy; the subsequent feasibility of randomized comparative studies will be assessed.

nova página do texto(beta)

nova página do texto(beta)