Introduction

In 2010, nearly 9 million new cases of tuberculosis (TB) were reported, which caused 350,000 deaths in HIV-infected patients and 1.1 million deaths in non-HIV-infected patients1. The classic form of presentation of TB is pulmonary, although disseminated tubercle bacilli can remain dormant in all tissues during the initial infection. Other studies have reported extrapulmonary TB with approximately 4.5% of new cases of active TB, which is more frequent in elderly patients. The sites included are lymph nodes, blood, genitourinary tract, bones, joints, meninges, peritoneum, adrenal glands, pericardium, and miscellaneous sites2.

Primary TB of the musculoskeletal system was first described in 1886. Since then, this entity has been observed as rare. Strictly speaking, this form of TB does not occur, except by accidental inoculation by means of a contaminated needle. The term primary tuberculous myositis is used to describe the clinical condition, in which the predominant lesion in the event of hematogenous TB occurs in the muscle. Hematogenous dissemination of the tubercle bacillus to the muscle has been described in a few cases and is, therefore, exceptionally rare3.

The extension to the chest wall has been due to direct extension of TB from the pleura and ribs, specifically affecting the mammary gland. Conversely, TB of the pectoralis major is extremely rare and case reports are scarce4,5.

Muscle tissue is resistant to tubercle bacillus, the reason for this resistance is unclear, but it has been attributed to the low amount of oxygen in muscle tissue and the presence of lactic acid6,7.

Case presentation

A 39-year-old female patient is a public hospital administrator, with no significant medical history regarding her current condition. She was consulted for presenting a 3-month progressive condition characterized by the presence of a tumor at the level of the anterior right hemithorax accompanied by stabbing pain that increased in the past 2 weeks. During its evolution, the patient denied having any respiratory symptoms or fever. In addition, she denied being in contact with people with the presence or a history of respiratory disease and pulmonary TB. She consulted with a general practitioner who requested a chest computed tomography (CT) scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

On examination, a tumor of approximately 4 × 4 cm was found at the level of the right parasternal region between the fourth and fifth intercostal space, of hard consistency that had not adhered to deep planes and painful to touch. No cervical or supraclavicular adenomegaly was palpated. Lung airways with good inspiratory and expiratory flow rate rule out pleuropulmonary syndrome.

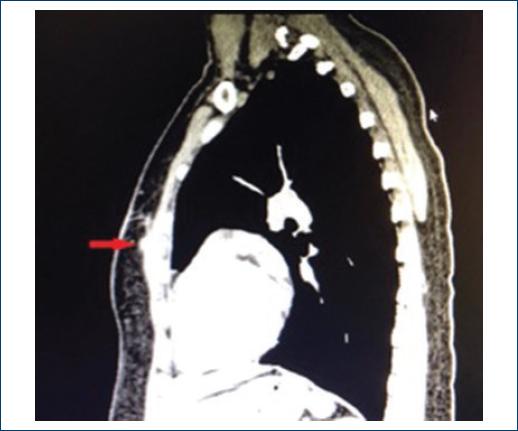

The axial tomography showed an isodense tumor of approximately 4 cm that was at the level of soft tissues above the right pectoralis major muscle, with 3 mm walls and central necrosis areas. The lung parenchyma did not show alveolar-occupying lesions and no signs of lymph node involvement in the mediastinum (Figs. 1 and 2). MRI confirmed the presence of tumor at the level of soft tissues in the right hemithorax (Fig. 3). Laboratory tests such as blood cytometry, blood chemistry, and coagulation times were normal. Serology for HIV tested negative.

Figure 1 Computerized axial tomography scan, the arrow indicates hypodense lesion affecting soft tissues of the anterior wall of the left hemithorax.

Figure 2 Sagittal computed tomography scan, the arrow indicates hypodense lesion affecting the anterior surface of the pectoralis major muscle of the anterior wall of the left hemithorax.

Figure 3 Magnetic resonance imaging, the arrow indicates cystic lesion adherence to the left pectoralis major muscle.

An excisional biopsy of the lesion was performed, which was attached to the pectoralis major muscle with the above-described diameters and presented caseous material. The histopathological study of the lesion reported the presence of striated muscle remains with fibrosis, accompanied by central necrosis, abundant polymorphonuclear cells, and giant cells included. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) report of the tissue was positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Therefore, the patient was referred to the department of infectious diseases, where the treatment for TB started based on a quadruple scheme with doTBal for 6 months. During her follow-up at 6 months, the patient is asymptomatic. Surgical site with proper scar healing process. CT control study was conducted, in which a fibrotic process was reported, at the level where the lesion was previously found (Figs. 4 and 5).

Discussion

Chest wall TB is a very rare condition. It is a typically chronic infection, and chronic chest wall infections can be found in soft tissues, cartilage, and bones8,9. In this case study, it is related to the growth of a localized lesion on the chest wall restricted to the soft tissues.

It represents 10% of all types of extrapulmonary TB and its presentation is 1-5% of all musculoskeletal TB cases10,11. It should be considered in immunocompetent patients12,13. The main risk factor is to have a history of TB, which is reported in up to 70-80% of cases14. Active TB has been reported to be present in 20-60% of patients with chest wall TB15. On the aforementioned occasion, the patient presented without any previous history of exposure to people with pulmonary or extrapulmonary TB. The only important fact that could be related is that she is a public hospital administrator, which could probably be related to any exposure.

There are three mechanisms in the pathophysiology that could lead to the development of chest wall abscess: the first is the direct extension from a pleural or pulmonary condition. The second is a hematogenous spread in a large part of extrapulmonary TB and the third is by direct extension due to tuberculous mediastinal lymphadenitis16.

There are two variants of chest wall TB in soft tissues, one in the form of an abscess and another as a tuberculoma. The muscles in which TB infection has been identified are described in the following order: brachial biceps, right femoral rectum, psoas, rectus abdominis, gluteus maximus, and the submasseteric space17,18. The reason for the infection in these structures being rare has been assigned to the high content of lactic acid in the muscles, the absence of lymphatic tissue, a high blood flow, and the high percentage of muscle differentiation19. Therefore, it is worth highlighting the case presented here, which involved only a soft-tissue lesion of the chest wall, with permeation toward the pectoralis major, ruling out any previous respiratory symptoms.

A common symptom described in cases of chest wall TB is a single palpable mass. The tuberculous abscess has a strong predilection for sternal margins. This has been suggested due to infection of the internal mammary lymph nodes secondary to primary pulmonary disease. The abscess may have a slow and generally asymptomatic evolution that can mimic a tumor because it is painless at the beginning and becomes painful within 2 months, which is related to the presentation of the case reported in this study20,21.

CT scans and excisional biopsy facilitate early diagnosis and effective management. CT scans demonstrate the nature and extent of soft-tissue collections, as well as possible intrathoracic adenopathy and bone erosions. It is generally observed as a juxtacortical mass in soft tissues with low central attenuation and peripheral enhancement22,23. Soft tissues and intramuscular abscesses are more visible with the use of MRI24. In our case, two imaging studies were performed that showed the lesion restricted to soft tissues, but this not only provided the diagnosis, it also served as a guide to assess the location of the lesion and to rule out other associated lesions in lung and ganglion tissue.

A more rapid diagnosis for M. tuberculosis can be performed by means of molecular techniques with the PCR, which has also shown greater specificity and sensitivity compared to conventional methods (staining for acid-resistant bacilli and the same culture)25-27. Therefore, in our case, PCR for TB was used, which gave us the definitive diagnosis regarding the nature of the lesion.

The initial recommended medical treatment is a 6-9 months quadruple therapy based on rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol followed by another 4-7 months regimen with rifampicin and isoniazid28. This treatment was applied to our case during a period of 6 months, with complete remission of the lesion at 6 months of follow-up.

Conclusion

We have described the case of a patient with TB at the level of the pectoralis major muscle. The localization is presumed to be due to the hematogenous spread of M. tuberculosis of an unknown origin, as the presence of recent or old lung injury was not evidenced and as reported in the literature. TB lesions at the muscular level are extremely rare due to hypoxia and lactic acid release conditions to which the muscle is exposed, which renders early diagnosis of extrapulmonary TB difficult. Regarding this particular patient, there was no previous respiratory symptomatology, and the tumor and pain were the only symptoms that the patient presented. Thus, this could to the assumption of a lesion of another nature such as lipoma, abscess, infectious or traumatic osteochondritis, or even a more rare soft-tissue neoplasm, such as sarcoma and chondroma. Because of the way in which the lesion was presented, its chronic nature, and the increase in pain, it was decided to remove it completely. The reason that led us to conduct the PCR for TB study was that, at the time of the resection and excision of the lesion, there was an outflow of caseous material, and the diagnosis was reached through this medium. On this diagnosis, the patient received a 6-month antibiotic therapy, with full remission of the symptoms and chest lesion shown by imaging exams. Due to its rare localization and, above all, the absence of prior exposure to TB, a clinical case of the abovementioned soft-tissue TB is reported. Although, it can be quite a challenge to reach an early diagnosis. Therefore, it is always necessary to suspect this type of lesions to avoid spreading to other tissues, and it is of foremost importance to suspect it when macroscopic findings show the presence of caseous material.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)