Introduction

"Burnout syndrome" is a psychological state clinically defined as emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a feeling of decreased personal achievement1-4.

Even when it is not restricted only to physicians, it mainly affects people who interact with physically and emotionally disabled people such as nurses, rescuers, volunteers, or social workers5.

Several studies demonstrate that a high proportion of physicians experiment stress or burnout syndrome with a negative consequence for themselves, their families, coworkers, and patients5-11.

Burnout syndrome can affect a physician's job satisfaction, as well as the quality attention they give12-15. The burnout syndrome is much more common to be found in physicians than other diseases as depression, drug abuse, or even suicide16.

In health-care personnel, high levels of this syndrome have been reported with prevalence rates from 0% to 70%; probably specific groups of physicians or health-care providers have different risk susceptibility to develop the syndrome17.

Factors leading to burnout syndrome have been widely described4,13,16,18-20. The most recognized factors are lack of autonomy, difficulty to find a balance between professional and personal life, excessive administrative duties and large numbers of patients to look after21. Recently, specific etiological factors for burnout syndrome have been proposed, such as inadequate management of bioethical aspects in the medical practice22-25, length of the medical career12,20,26, philosophy of delayed gratification8,20,27, and long working hours11,21,26.

Materials and methods

Design: A cross-sectional, prevalence study in a single institution

The study was submitted and approved by the Ethics and Research Committee from our Institution; it complies with the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 (World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki) and Ethical Principles for Medical Research involving human subjects. All data obtained were anonymous; no record of the participants whatsoever was obtained.

In a sample of 84 surgeons, surgery residents, and medical students; burnout syndrome was measured using the Maslach Burnout Inventory28-30. In agreement with its manual, the presence of the syndrome was defined as the association of high levels of depersonalization and emotional exhaustion, together with low levels of personal satisfaction29.

Other individual variables were measured: age, gender, and academic degree. Some variables previously described associated with burnout syndrome were measured specifically through an anonymous survey: academic knowledge about burnout syndrome (ability to define it correctly), bioethical education (defined as having attended at least one semester to a Bioethics Program, either undergraduate or postgraduate studies), and working hours per week. Objectives of the study, methodology and contact information of the main researcher were included in a brief paragraph of the survey and the inventory; an informed consent was also used to participate in the study.

Twelve subjects declined to answer the questionnaire

Prevalence was calculated for the whole sample and subgroups. Mean ± standard deviation, median, and confidence interval (CI) values were used for continuous variables; absolute values and percentages were used for discrete variables related to demographic data.

To calculate the relationship between clinical parameters and burnout syndrome, Fisher's exact test, or Chi-square test was used for categorical variables and t-test, Mann-Whitney U-test or Kruskal-Wallis for continuous variables; a multivariate logistic regression analysis was applied to identify predictive variables; SPSS software version 19 was used. Statistical significance was determined as p < 0.05.

The method is graphically described in a flow diagram in figure 1.

Results

Twelve individuals either did not complete or did not return the survey. Demographical data of the 72 subjects are presented in table 1; most of the subjects were surgery residents, least were medical students; and few of them were women.

Table 1 Demographic data of the 72 subjects included

| Age (years) | Mean | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Interval | ||

| 19-65 | 31.4 | 11.6 |

| Gender | Number | Percentage |

| Female | 27 | 37.5 |

| Male | 45 | 62.5 |

| Medical position | ||

| Student | 9 | 12 |

| Resident | 41 | 57 |

| Surgeon | 22 | 31 |

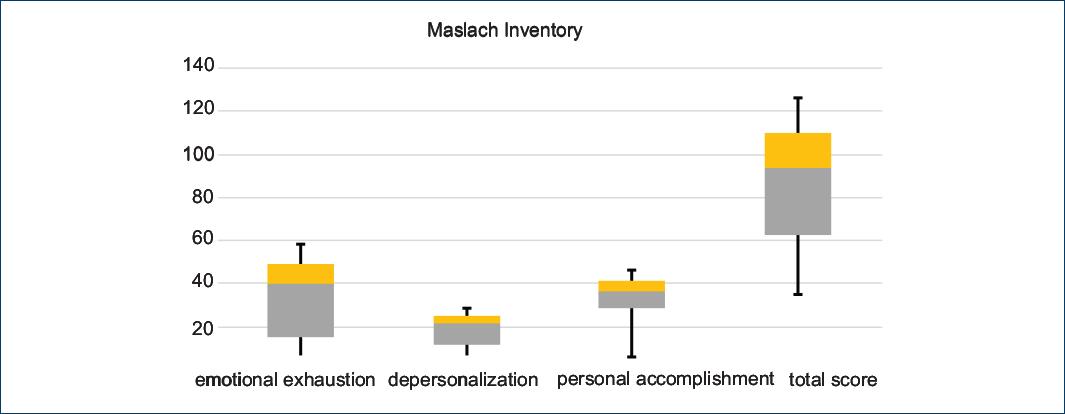

Figure 2 shows the grades obtained in the 72 subjects within the three measures of the Maslach Burnout Inventory: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal realization, as well as a total grade28-30.

Figure 2 Scores of 72 subjects in the three measurements of Maslach inventory; emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, personal accomplishment, and total score.

Emotional exhaustion in the Maslach inventory subscale varies from 5 to 54 points. Scores of 27 or more are considered a high level of burnout syndrome, scores between 19 and 26 are considered intermediate levels, and scores under 19 indicate low burnout syndrome levels28. In the present study, grades varied from 6 to 54 points and the median was 39.5. Forty-four subjects (61%) presented a high level, one subject (1%) intermediate level, and twenty-seven (37.5%) low level.

The depersonalization subscale varies from 1 to 30 points. Scores above ten are considered a high level of burnout syndrome, scores between 6 and 9 fit with intermediate levels, and scores under six indicate low levels of this syndrome28. In the present study, grades varied from 6 to 30 points, and the median was 21.5. Fifty-nine subjects (82%) presented a high level and 13 (18%) intermediate level.

On the opposite, the personal accomplishment subscale is inversely proportional to the burnout syndrome level. It varies from 1 to 48 points. Scores above 39 indicate a high level of personal accomplishment and a low level of burnout syndrome. Scores between 31 and 38 indicate intermediate levels, and scores under 31 indicate a high level of burnout syndrome28. In the present study, grades varied from 6 to 47 points and the median was 36. Twenty-three subjects (32%) got a high level of personal accomplishment, 30 (42%) got an intermediate level, and 19 (26%) got a low level.

The Maslach inventory final grade adds up scores from the three subscales and ranges from 3 to 132 points. It is considered as the gold standard to diagnose burnout syndrome28-30. Scores above 67 points indicate a high level of burnout syndrome, scores between 34 and 66 indicate an intermediate level, and scores under 34 indicate a low level of burnout syndrome. In the present study, grades ranged from 35 to 122 points, and the median was 94. Forty-seven subjects (65%) got a high level of burnout syndrome; meanwhile, twenty-five (36%) got a low level.

In the present study, the global prevalence of burnout syndrome was 65% (CI 95% 54-76). The prevalence in medical students was 67% (CI 95% 36-88), in residents 76% (CI 95% 61-86) and in surgeons 45.5% (CI 95% 27-66), no significant statistical difference was found between them (p = 0.056).

Table 2 shows the results of the 72 subjects related to burnout syndrome and variables as gender, medical position, working hours per week, and bioethical preparation. No significant differences were found between gender or medical position and high or low burnout syndrome levels; however, we certainly found a significant difference between both groups related to age (young subjects are more susceptible to burnout syndrome), working hours per week (subjects with more working hours showed higher susceptibility to burnout syndrome), and bioethical preparation (subjects with no bioethical training were more susceptible to burnout syndrome).

Table 2 Comparison between groups with high and mild levels of burnout syndrome, related to variables such as age (mean and interval are shown), gender, medical position, working hours per week, and bioethical training (number and percentage are shown) in 72 subjects studied

| Group with high level of burnout syndrome (n = 47) | Group with mild level of burnout syndrome (n = 25) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 29.8 (19-65) | 34.2 (19-65) | 0.020 |

| Gender (%) | |||

| Female | 16 (59) | 11 (41) | 0.406 |

| Male | 31 (69) | 14 (31) | |

| Medical position (%) | |||

| Student | 6 (67) | 3 (33) | 0.056 |

| Resident | 31 (76) | 10 (24) | |

| Surgeon | 10 (45.5) | 12 (54.5) | |

| Working hours per week (%) | |||

| 92 or more | 31 (76) | 10 (24) | 0.034 |

| < 92 | 16 (52) | 15 (48) | |

| Bioethical training (%) | |||

| Yes | 4 (14) | 25 (86) | 0.000 |

| No | 43 (100) | 0 (0) |

To determine if age and no bioethics training were associated or independent factors, both were analyzed with Chi-square or Fisher's exact test using as independent variables: age, gender, medical position, and working hours per week; and bioethics training as a dependent variable. The results are shown in table 3. No significant difference among groups was found.

Table 3 Comparison between groups with or without bioethical training, related to variables such as age (mean and interval are shown), gender, medical position, and working hours per week (number and percentage are shown) in 72 subjects studied

| Group with bioethical training (n = 29) | Group without bioethical training (n = 43) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 33 (19-65) | 30.2 (19-65) | 0.1 |

| Gender (%) | |||

| Female | 12 (44) | 15 (56) | 0.577 |

| Male | 31 (69) | 14 (31) | |

| Medical position (%) | |||

| Student | 3 (33) | 6 (64) | 0.261 |

| Resident | 14 (34) | 27 (66) | |

| Surgeon | 12 (54.5) | 10 (45.5) | |

| Working hours per week (%) | |||

| 92 or more | 14 (34) | 27 (66) | 0.222 |

| < 92 | 15 (48) | 16 (52) | |

Multivariate logistic regression analysis established as risk factors: age under 27 years (p = 0.02), more than 92 working hours per week (p = 0.04), and lack of bioethics training (p = 0.000); as shown in figure 3.

Discussion

Burnout syndrome transcends the affected physician since it is a psychological state where "a complete interest and emotional concern for the patients is lost, considering them as total indifference and even as a dehumanized manner"5.

It is triggered as a response to chronic work stress, and it generally leads to a decrease in adequate patient care, increased medical errors, secondary depression, and drug abuse18,31,32.

Causes of burnout syndrome in physicians have been widely described4,13,16,18,27. Conventionally, the main causes of stress have been: lack of autonomy, difficulty to find a balance between personal and professional life, excessive administrative duties, and a large number of patients21. The interaction and influence of these factors, together with other working characteristics, form a complex phenomenon that affects personal responsibilities, personality, health, and job enthusiasm.

Nowadays, there is a current and renovated interest to identify factors associated to burnout syndrome, among them: weakness related to hierarchical or bureaucratic structures of control that regulate daily clinical practice, inefficient or blocking job politics, lack of material or financial sources to work properly33, moral affliction31,32,34-37, and ethics issues when making decisions38. Besides, an increased interest has been noticed to identify vulnerable populations within medical environment: surgeons7,13,14,39, oncologists8,11,40, geriatricians41, critical care providers31, psychiatrists42,43, and students and training physicians9,40.

Moral, ethical, and bioethical aspects relationship with burnout syndrome have been recently expressed by some authors31,35,36, who considered this syndrome as the most negative consequence of moral distress. Moreover, they emphasize the connection of this syndrome with the experience of a patient's death and bioethical influence on making decisions. These authors also notice that "there are no studies speculating about this correlation "35.

The most important finding of our study is the statistically significant correlation between bioethics training and burnout syndrome5,34,37,38.

Our research has established bioethical knowledge as a protective factor in burnout syndrome appearance, validating it through a logistic, univariate and multivariate regression analysis, demonstrating a statistical significance between a lack of bioethical preparation and high levels of burnout syndrome (odds ratio 7.25, CI 2.9-18, p = 0.000).

A recent manuscript revealed a similar analysis between "moral distress" and burnout syndrome31, also finding a positive association (p = 0.010) between moral distress (defined as the impossibility to act according to a person's values and his/her obligations due to external and internal limitations) and burnout syndrome. Similar to our results, they found that moral distress is independently associated with burnout syndrome appearance (odds ratio 2.4, CI 1.19-4.82, p = 0.014).

It has been described that the lack of academic tools necessary to analyze effectively bioethical problems in medicine, is one of the most important reasons to develop chronic stress in residents and surgeons22-25. Many reasons exist: a lot of issues in the modern practice of medicine are quotidian dilemmas in physician's duty; decisions about delicate matters should be firmly based in bioethical training and knowledge; and not assigned just to physicians' free will or linked to common morality22. Common conflicts related to proper medical attention offered to patients with incurable diseases, such as disagreements about the best treatment alternatives, therapeutic obstination, and decisions in terminal patients, have all been documented as risk factors for developing burnout syndrome44-48.

In the present study, in agreement with other reports8,9,11,40, it has been found that young physicians (< 29 years old) are more susceptible to burnout syndrome (p = 0.020), not related to their academic degree (no significant difference was found between medical students and surgery residents).

Moreover, the present study showed a statistically significant association between high working hours per week and an increased burnout syndrome level (p = 0.034); similar to the previous reports12,20,26. Other trials have also found an association with a high working load (number of cases per week)11.

Our study has several limitations: its transversal design, the results reported refer to a single population in one institution, which causes homogeneity and lack of randomness in the studied population; circumstances or reasons of the subjects that declined to participate were not examined which represented bias against the study. Its design did not allow us to determine causality.

Conclusions

About 65% prevalence of burnout syndrome has been found in a population of physicians of different ages, and academic degrees from the department of surgery. The prevalence found is very high, similar to that reported in other studies related to surgical specialties, which highlight the magnitude of the problem. Even when recognized, very few programs are directed to detect the phenomena, and to the best of our knowledge, no protocols are focused on preventing it in our ambit. Because of its high prevalence and also because of its serious and deleterious consequences, there is a strong need for further research about the subject and its causes.

We have found two main factors associated to higher level of burnout syndrome: age and bioethical knowledge; young doctors independently from its academic degree are more susceptible to develop the phenomena; interestingly, bioethical knowledge is a protective factor in burnout syndrome appearance; the relationship between burnout syndrome and moral, ethical and bioethical aspects has been recently described in medical literature.

Further investigation could validate these findings; meanwhile, we would like to highlight that age of a given person cannot be modified, but bioethical preparation can, so this work could motivate to make adjustments to the curricula in medical colleges and residency programs with the added value of giving to young doctors strategies to cope with burnout syndrome.

nova página do texto(beta)

nova página do texto(beta)