Introduction

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) is the most commonly performed bariatric procedure. The most important complications of LSG are staple line leakage and bleeding. Their incidence varies between 0.5-5% and 1.7-13.7%, respectively1,2. Surgeons have tried a variety of staple line reinforcement (SLR) techniques to minimize complications. Using synthetic/biological materials, fibrin glue, suturing, clipping, and their combinations are well-known methods for SLR. An ideal SLR method should be simple, cost-effective, minimizing complications, and not prolonging the operation time as much as possible.

Stapler line cauterization is not a new technique for staple line bleeding control (SLBC). The use of bipolar cautery on the stapler line is widely known3,4, but there are limited articles on the use of monopolar cautery2,5. To the best of our knowledge, there is no other study comparing the effect of monopolar cautery and another SLR method on bleeding and leakage for SLBC in LSG. Our aim was to compare the results of continuous invaginating hand-sewn suture of the stapler line and monopolar cauterization in terms of bleeding and leakage in LSG.

Materials and methods

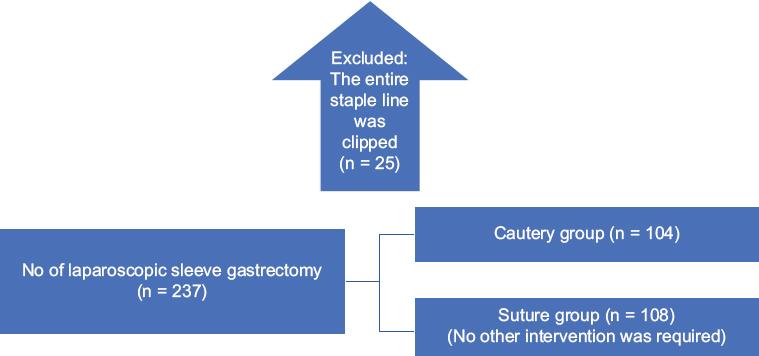

This study was approved by the University Ethics Committee (2021/1735). All procedures were performed with the ethical standards of 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study. The patients were evaluated by a team of dietitians, endocrinologists, psychiatrists, and bariatric surgeons before surgery. Inclusion criteria were patients with a body mass index (BMI) > 40 kg/m2 or 35-40 kg/m2 and with at least one obesity-related comorbidity. Patients who had prior gastric surgery were not included in the study, and patients using other methods for SLBC were excluded from the study (Fig. 1). Since monopolar cauterization of the staple line and continuous invaginating hand-sewn suturing is the preferred methods in our clinic in consecutive periods, patients were selected in two different periods.

Abdominal ultrasonography was performed in all patients before the operation, and upper gastrointestinal system endoscopy was performed in patients with reflux symptoms.

Age, gender, BMI, comorbid diseases, anticoagulant drug history, pre-operative INR level, prior abdominal surgery, pre-operative and post-operative hemoglobin levels, operation data (amount of bleeding, duration of surgery, additional interventions on the stapler line and perioperative complications), post-operative first 3 days of visual analog scales (VAS) scores, amount of abdominal drainage, complications during follow-up, and length of hospital stay were recorded. Prior abdominal surgeries were categorized as lower and upper abdomen. VAS ranging from zero (painless) to 10 (worst) was used to evaluate postoperative pain6. VAS scores were asked in the morning before any analgesic requirement. Postoperative complications were categorized according to the Dindo-Clavien classification7.

Transection and SLBC technique

Transection was started 6 cm proximal from the pylorus. The first of two staples were green loads (4.1 mm) and others were blue loads (3.5 mm) (Endogia, 60-mm, Covidien, Norwalk, CT, USA or 60-mm Echelon, Ethicon Endosurgery Cincinnati, OH).In the monopolar cautery group; SLBC was achieved with monopolar electrocautery (in coagulation mode - 40 Watts) connected to endoscopic scissors (Only the hemorrhagic foci were touched for 1 s). In the suturation group; for SLBC, the staple line was invaginated and sutured continuously with 3-0 monofilament polypropylene suture (Prolene, Ethicon Inc., a Johnson and Johnson Company, Somerville, New Jersey). Staple lines were inspected for bleeding by increasing the systolic blood pressure above 140 mm Hg. Finally, methylene blue test was performed for leakage control.

Post-operative follow-up

Oral intake was started on the 1st post-operative day and discharge was planned on the 2nd or 3rd post-operative day. All kinds of surgical and medical complications were recorded in our database, which started in previous periods and was followed up prospectively. For this study, we retrospectively analyzed data on leakage, bleeding, and reoperation.

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and functional tests were performed when reflux or stenosis symptomatology was detected.

Definitions

Leakage was defined as the presence of extragastric contrast material on tomography8. Bleeding was defined as hemorrhage requiring surgery or transfusion. Hemorrhagic drain yield consistent with a hemoglobin drop managed without transfusion/surgery was also recorded as bleeding. Stenosis was defined as acute (i.e., inability to start oral liquids, nausea, and vomiting) or chronic complaints (i.e., intolerance to solids, frequent vomiting, increased reflux complaints, low weight, and malnutrition) in the presence of findings at contrast swallow studies and gastroscopy. In the upper GI contrast study, the segment that could be seen as stenotic but passed through endoscopically was accepted as functional stenosis.

Statistics

Data were analyzed using SPSS software version 23 (IBM Corp., NY, USA) and Excel 2016. Continuous and categorical variables were compared using unpaired t-tests. Categorical variables were compared with each other using either the Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test. Statistical significance was accepted as p < 0.05.

Results

Between January 2017 and March 2021, a total of 237 morbid obese patients were treated with LSG. Two hundred and twelve patients (169 (79.9%) women, mean age 36.2 ± 10.2 years, and mean BMI 45.1 ± 1.58 kg/m2) were included in the study.

Demographic, perioperative, and post-operative characteristics of the patients are summarized in table 1. Intraoperative complications developed in seven patients, one in the cautery group and six in the suture group. All these complications were treated without conversion to open surgery. There was no difference in blood loss between the groups (p = 0.12), but the operation time was longer in the suture group (p < 0.05). Post-operative complications were developed in seven patients, four of them bleeding and three of them leakage from the stapler line. Among the four patients who developed bleeding (three patients were in the cautery group, one patient was in the suture group), two had melena and decrease hemoglobin levels (Dindo-Clavien 2), intra-abdominal hemorrhage was found in the other two (hemorrhagic drain yield) (Dindo-Clavien 2). All three patients with leakage from the stapler line were in the cautery group. One of the patients was successfully treated with conservative methods (Dindo-Clavien 2), but the other two patients underwent revision to RYGB (on the 15th and 17th days postoperatively) (Dindo-Clavien 3B). There was no difference between the groups in terms of hemoglobin decrease (p = 0.63). Post-operative VAS scores gradually decreased over days, and the 3-day VAS scores of both groups were similar (Table 1). There was no mortality in either group.

Table 1 Demographic, perioperative, and post-operative data of patients

| Parameters | Cautery (n = 104) | Suture (n = 108) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (Female/Male) | 85/19 | 84/24 | 0.48 |

| Age | 33.8 ± 9.9 | 31.8 ± 10.1 | 0.15 |

| BMI | 44.1 ± 5.7 | 43.8 ± 4.6 | 0.65 |

| Obesity related comorbidity | 40 (38%) | 21 (18%) | < 0.05 |

| 1 | 29 (28%) | 12 (11%) | |

| 2 | 10 (9%) | 7 (6%) | |

| 3 | 1 (1%) | 2 (1%) | |

| Prior abdominal surgery | 35 (33%) | 26 (24%) | 0.12 |

| Upper quadrant | 7 (6%) | 8 (7%) | |

| Lower quadrant | 24 (23%) | 18 (17%) | |

| Both | 4 (4%) | 0 | |

| INR | 0.99 ± 0.08 | 0.96 ± 0.09 | 0.66 |

| Intra operative complications | 1 | 6 | 0.16 |

| Nasogastric tube trapping into | 1 | 1 | |

| staple line | 0 | 1 | |

| Staple line failure | 0 | 1 | |

| Small intestinal injury | 0 | 3 | |

| Liver injury | |||

| Duration of surgery (min) | 101.6 ± 46.6 | 123.1 ± 40.1 | < 0.05 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (ml) | 39.3 ± 63.2 | 28.4 ± 31.9 | 0.12 |

| Postoperative complication | |||

| Staple line bleeding | 3 (2.9%) | 1 (0.9%) | 0.35 |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 2 | 0 | |

| Intra-abdominal hemorrhage | 1 | 1 | |

| Staple line leakage | 3 (2.9%) | 0 | 0.09 |

| Stenosis | 0 | 0 | |

| Mortality | 0 | 0 | |

| Post-operative hemoglobin decrease | 1.4 ± 1.1 | 1.3 ± 1.0 | 0.63 |

| VAS score post-operative day 1 | 3.9 ± 2.2 | 3.9 ± 1.3 | 0.98 |

| VAS score post-operative day 2 | 2.6 ± 1.8 | 2.5 ± 1.2 | 0.44 |

| VAS score post-operative day 3 | 1.8 ± 1.5 | 1.7 ± 1.1 | 0.80 |

| Length of hospital stay | 3.5 ± 2.6 | 3.8 ± 2.4 | 0.35 |

Obesity related disease: Diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cardiac disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, goiter. In bold: statistical significance was accepted as p<0.05.

BMI: Body mass index; VAS: Visual analog scale.

Discussion

Although LSG is technically perceived as a simple operation, low complication rates depend on fine details. It is a fact that the more experience the surgeon has, the less complications will be. However, Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative showed that complications such as infection and obstruction decreased with increasing experience, but bleeding and leakage did not change significantly9.

As with all surgical procedures, LSG has a learning curve, studies have revealed that 60 cases are needed to pass the learning curve and reduce complication rates in LSG10,11. However, there are also studies showing that significant surgical complications occur after the completion of the learning curve12. Based on this, we conclude that there is a need for optimization of surgical technique as well as experience to prevent bleeding and leakage.

With the increasing use of stapler tools in routine surgery, staple line complications have also increased. LSG is the procedure with the longest staple line in gastrointestinal surgery and the majority of LSG complications are associated with this line. Therefore, most of the studies on the prevention and management of staple line complications in digestive system surgeries are related to LSG.

Control of staple line bleeding with bipolar cautery is a known method3,4. However, the number of studies on the use of monopolar cautery is very few2,5. To the best of our knowledge, there is no other study comparing monopolar cautery with continuous invaginating hand-sew suturing for SLBC after LSG. In our study, we found that there was no statistical difference between the two methods in terms of complications, and the operation time was shorter in the cautery group. Based on these results, we conclude that monopolar cautery is safe and effective for SLBC during LSG. In addition, being practical and inexpensive are an important reason why it is preferred13.

Various methods have been used for SLBC, such as sutures, clips, fibrin glue, or buttressing materials. Most of these methods have been studied in LSG patients and there is no consensus on the best method13-16. In our daily practice, we have never used stapler line supporting materials and preferred monopolar cauterization alone. We transferred this practice to our laparoscopic routine from our open surgical experience of 20 years. From the beginning of our bariatric surgery program (March 2006), we have performed more than 2000 bariatric procedures so far, with this hemostasis technique and have found no adverse effects of monopolar cauterization for SLBC. We could not find any other study comparing the use of monopolar cauterization with any other method for SLBC in LSG. In a limited number of publications, bipolar cauterization for SLBC in LSG was rarely performed and staple line leak rates were reported as 1%3,4. In another study evaluating the effect of monopolar cauterization in sleeve gastrectomy, the leakage rate was 2.6%5. In our study, this rate was 2.9%. Since staple line leak rates are reported to be between 0.5% and 5% after LSG17, the monopolar cauterization method should not be considered to increase staple line leaks. Monopolar cautery does not have a mechanical effect like sutures or clips, so more intraluminal bleeding can be expected. However, in our study, no significant difference was found between the two groups in terms of bleeding, and the rate of intraluminal bleeding in the cautery group (1.9%) was similar to the literature18.

Monopolar cautery application shortened the operation time as expected. Suturing the stapler line is a long process, although it also depends on technical skill. In another study comparing monopolar cautery and clip application in RYGB, no difference was found between the two methods in terms of operation time, and it was thought that the smoke caused by cauterization prolongs the operation time2.

Suturing the staple line may be considered safer in terms of preventing bleeding, but it has disadvantages. First of all, laparoscopic suturing is an application that requires skill. In the greater curvature, the vascular structures lie perpendicular to the staple line. Therefore, there is a possibility that continuous suturing will not stop bleeding. The suture may cause collateral bleeding and hematoma at the suture site, which requires extra hemostasis. If care is not taken during suturing, stenosis may occur, especially in the proximal stomach where the “angle of his” is located. Or, insufficient fundus resection can be performed for fear of stenosis12.

The increase in the number of bariatric surgery operations creates a burden on general health expenditures. Therefore, the economic burden of surgical equipment is becoming more and more important. A study investigating the efficacy of SLR materials revealed that they increase the cost per patient without the advantage of shortening the length of hospital stay19.

Although the lack of cost analysis is a limitation of our study, we think that monopolar cautery is a cheaper method compared to others, since it does not require the use of additional materials and does not prolong the duration of surgery and hospitalization.

The SLR is only one part of the LSG procedure and there are key points to consider for a successful LSG besides the SLR technique. At the end of the operation, the entire surgical area and trocar sites should be carefully checked for bleeding. A suitable stapler cartridge should be selected for gastric transection, and sufficient distance should be maintained so that no stenosis occurs in the incisura angularis and gastroesophageal junction before firing the stapler. Gastric tissue should be compressed for at least 15 s and then transected. Successful preoperative glycemic control, avoidance of post-operative hypertension and adherence to diet in the post-operative period are some of the other important points of success.

This study has some limitations. Our study is retrospective and includes patient groups who were operated in consecutive periods. Larger studies are needed due to the low number of patients and low complication rates.

Conclusion

Despite increased equipment availability and technical experience, staple line leakage and bleeding are still major problems and both are currently major research topics. We think that monopolar cauterization gives similar results to the suturing technique, which is considered reliable for the control of bleeding from the staple line in LSG. Monopolar cauterization is a safe and efficient method as well as inexpensive.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)