Introduction

Kidney transplantation (KT) is the best treatment option for patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) compared with dialysis therapy. It is associated with improved quality of life and better survival in patients with ESRD1-3. Advances in immunological therapy and management strategy have increased the survival of kidney recipients and their grafts. Despite short-term increases in graft and patient survival, long-term outcomes are still not as expected4-12. Mortality after KT is still a serious problem.

In developed countries, underlying causes of deaths among kidney recipients have changed over time, and infection-related mortality has decreased, while cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) have become the leading causes of mortality13,14. Since the incidence of fatal infections after KT has decreased over time, current data on specific infectious causes of mortality are scarce13.

This study aims to share 10-year outcomes after KT and reveal the diseases leading to death among kidney recipients.

Materials and methods

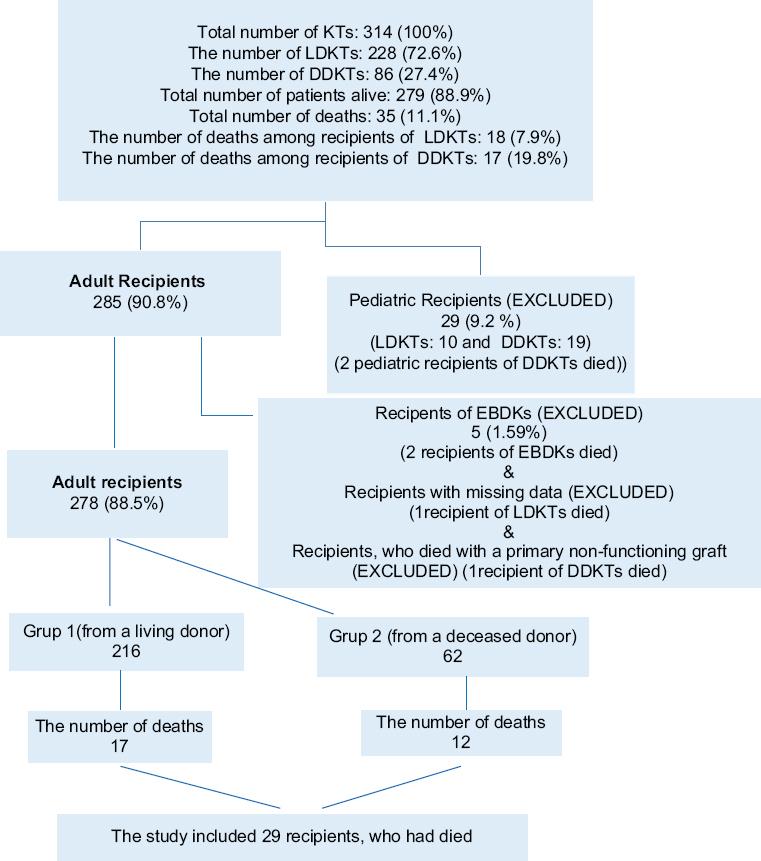

Medical data of the patients, who had undergone KT at a tertiary center between November 2010 and December 2020, were retrospectively reviewed. Inclusion criteria were adult kidney recipients, who had died. Exclusion criteria were pediatric recipients, recipients of en bloc and dual KT (EBDK), recipients with missing data, and recipients, who had died with a primary non-functioning graft (PNFG). Figure 1 shows the flowchart of the recipients. Six recipients, who had died (2 pediatric recipients, 2 recipients of EBDK, 1 recipient with missing data, and 1 recipient, who died with a PNFG) were excluded from the study. The recipients were grouped according to their donor type: Group 1 (from a living donor) and Group 2 (from a deceased donor). Subgroup analyses were done for mortality by time-period post-transplant (within the 1st year and after the 1st year) and for infectious causes of mortality.

Evaluation of living donors and recipients

All recipients and living kidney donors (LKDs) underwent detailed clinical examination. A six-step process (Malatya Algorithm) was used for evaluation of both potential LKDs and recipients15. The evaluation of LKDs with standard criteria was conducted according to the principles set out by the Amsterdam Forum16. Due to serious organ shortage, as is the case globally, kidneys were recovered from the donors with both standard criteria and extended criteria (ECD). There are no universal criteria defining ECD. This refers to a higher risk when compared to that with a standard donor. The risk could be a disadvantage in the future not only for recipients, but also for LKDs. Table 1 provides a definition for ECD, which was applied and/or recommended by our clinic.

Table 1 The definition of the extended criteria donor

| Deceased donor | Living donor |

|---|---|

| Donor aged (≥ 60 and < 5)

Vascular or anatomic variations Kidney with simple cysts and/or stones Presence of infection (except sepsis) Ischemia time longer than 24 h Grafts with ATN (especially when CPR applied) ABO incompatible donors * It is not applicable in our country Donation after cardiac death * It is not applicable in our countrys |

Donor aged ≥ 60 Vascular or anatomic variations Simple kidney cysts and/or stones in one kidney, which is planned to be recovered. Donors with multiple cysts in one kidney or simple cysts and/or stones in both kidneys are not eligible for donation. ABO incompatible donors * It is not applicable in our country |

| Donor aged (≥ 50 - < 60), who have at least two

of the following criteria – Cerebrovascular accident – Hypertension – Diabetes Mellitus – Serum creatinine>1.5 mg/dL at time of donation |

Donor aged (≥ 50 - < 60), who have at least one

but no more than two of the following criteria – Previous history of cerebrovascular accident without serious sequelae – Hypertension (uncomplicated) – Diabetes Mellitus (uncomplicated) – Connective tissue disease (uncomplicated) |

| Donor aged (≥ 5 - < 50), who have at least one

of the following criteria – Cerebrovascular accident – Hypertension – Diabetes Mellitus – Serum creatinine>1.5 mg/dL at time of donation |

Donor aged (≥ 30 - < 50), who have only one of

the following criteria. Donation is not eligible if the

potential donors have two or more of the criteria. – Hypertension (uncomplicated) – Diabetes Mellitus (uncomplicated) – Connective tissue disease (uncomplicated) |

| *** Our clinic recommends not to recover kidney

from the potential living donor aged (≥ 18 - < 30) securing

donor interests If it is preferred, it would be appropriate for donor not to have additional diseases |

ATN: acute tubular necrosis, CPR: cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Delayed graft function (DGF) was defined as the need for dialysis within the 1st week of transplantation. The recipients were followed by the Nephrology Outpatient Clinic after having been discharged.

Immunosuppressive regimen

Immunosuppressive regimen included induction therapy with a polyclonal antibody preparation (antithymocyte globulin) or an anti-CD25 monoclonal antibody (basiliximab) and maintenance therapy (triple therapy with a calcineurin inhibitor [tacrolimus], an adjunctive agent [mycophenolate mofetil or mycophenolic acid], and corticosteroids). Short courses of “rescue” therapy were also required to treat episodes of acute rejection in some recipients.

Antimicrobial prophylaxis and treatment

All kidney donors received a single-dose of 2 g Cefazolin IV. Kidney recipients either received a Cefazolin 1 g IV every 8 h for 24 h (before 2013) or a single-dose of 1 g Cefazolin IV (through 2013 and beyond). In addition to Cefazolin prophylaxis, both empirical and adjusted antimicrobial therapies were given to recipients of donors with microbial growth on urine/blood/tracheal aspirate cultures and recipients with any infectious complications.

All kidney recipients received 3 months of Valganciclovir prophylaxis for CMV infection and 1-2 years of Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis for Pneumocystis carinii infection. Kidney recipients, who were at a high risk of developing tuberculosis (Tbc), received 9 months of isoniazid prophylaxis. Kidney recipients, who required AntiHBV therapy, received Entecavir or Tenofovir.

Ethics

The study was conducted according to the principles set forth by the Helsinki Declaration of 1975. Approval from the Human Ethics Committee of the Institution was obtained (approval number: 2021/1767).

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS 17.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). Continuous variables were presented as means with standard deviations (SDs), categorical variables were presented as numbers with percentages. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to analyze normality of the groups. The Student’s t-test was used for continuous variables with normal distribution. The Mann–Whitney U-test was applied for non-normally distributed variables. The Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables.

Results

Three hundred and fourteen patients had undergone KT between November 2010 and December 2020. Of these, 228 were living-donor KT (LDKT) and 86 were deceased-donor KT (DDKT). Of 314 recipients, 35 (11.14%) died. Twenty-nine recipients with a mean age of 51.7 ± 11.9 years (12 females and 17 males) were included in the study.

Immunosuppressive regimen included induction therapy with an antithymocyte globulin (n = 25) or basiliximab (n = 4) and maintenance therapy (triple therapy with a tacrolimus (n = 29), an adjunctive agent (mycophenolate mofetil (n = 16) or mycophenolic acid (n = 13), and corticosteroids (n = 29). Twenty recipients (68.9%) remained on their discharge immunosuppressive regimens, while nine recipients (31.1%) not. Short courses of “rescue” therapy were required to treat episodes of acute rejection in 6 recipients. Seven kidney recipients received a Cefazolin 1 g IV every 8 h for 24 h, eight recipients received a single-dose of 1 g Cefazolin IV. In addition to Cefazolin prophylaxis, both empirical and adjusted antimicrobial therapies were given to seven recipients of donors with microbial growth on urine/blood/tracheal aspirate cultures and seven recipients with any infectious complications.

The number of recipients in Group 1 and Group 2 was 17 and 12, respectively. The mean follow-up period of recipients was 34.41 ± 35.30 months and 25.25 ± 34.41 months in Group 1 and Group 2, respectively. The difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.478) (Table 2).

Table 2 The characteristics of the recipients and donors according to type of donors

| Characteristics | Total (n = 29) | Group I (n = 17) | Group II (n = 12) | (p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (recipient) | 51.75 ± 11.93 | 45.76 ± 10.68 | 60.25 ± 7.87 | 0.000 |

| Age (donor) | 50.55 ± 16.41 | 48.76 ± 10.34 | 53.08 ± 22.77 | 0.495 |

| Gender (recipient) | ||||

| Female | 12 | 6 | 6 | 0.471 |

| Male | 17 | 11 | 6 | |

| Gender (donor) | ||||

| Female | 10 | 7 | 3 | 0.449 |

| Male | 19 | 10 | 9 | |

| Ischemia time | 196.2 ± 74.7 (WIT, s) | 1204.25 ± 246.9 (CIT, min) | ||

| Follow-up time (months) | 30.62 ± 34.62 | 34.41 ± 35.30 | 25.25 ± 34.41 | 0.478 |

| Causes of ESRD | ||||

| Idiopathic | 14 | 8 | 6 | |

| DM | 7 | 5 | 2 | |

| HT | 2 | (-) | 2 | |

| GN | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| Others | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| Comorbid disease (recipient) | ||||

| Yes | 25 | 17 | 8 | 0.021 |

| No | 4 | (-) | 4 | |

| Pre-transplantation RRT | ||||

| Preemptive | 4 | 4 | (-) | |

| HD | 18 | 9 | 9 | |

| PD | 4 | 3 | 1 | |

| HD-PD | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| Mean duration of RRT (month) | 74.08 ± 66.29 | 22.07 ± 26.52 | 130.4 ± 46.5 | 0.000 |

| Extended criteria donor | 16 | 5 | 11 | 0.001 |

| Delayed graft function | 12 | 3 | 9 | 0.006 |

| Death with functioning graft | 23 | 13 | 10 | 1.000 |

| Gender (recipients with functioning graft) | ||||

| Female | 6 | 2 | 4 | 0.002 |

| Male | 17 | 11 | 6 | |

| Return to dialysis | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1.000 |

| RRT options from graft loss to mortality | ||||

| HD | 5 | 3 | 2 | |

| HD-PD | 1 | 1 | (-) | |

| Gender of recipients, who return to dialysis | ||||

| Female | 6 | 4 | 2 | 0.002 |

| Male | (-) | (-) | (-) | |

| Gender of donors, whose recipients return to dialysis | ||||

| Female | 1 | 1 | (-) | 0.633 |

| Male | 5 | 3 | 2 |

LDKT: living donor kidney transplantation, DDKT: deceased donor kidney transplantation, WIT: warm ischemia time, CIT: cold ischemia time, ESRD: end stage renal disease, DM: diabetes mellitus, HT: hypertension, GN: glomerulonephritis, RRT: renal replacement therapy, HD: hemodialysis, PD: peritoneal dialysis.

There was not significant differences between the groups in terms of recipients’ gender (p = 0.471) and donors’ gender (p = 0.449). The mean age of recipients was significantly higher in Group 2 (60.25 ± 7.87 years) compared to that in Group 1 (45.76 ± 10.68 years) (p = 0.000). The mean age of donors was 48.76 ± 10.34 years and 53.08 ± 22.77 years in Group 1 and Group 2, respectively. The difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.495) (Table 2). The mean warm ischemic time was 196.2 ± 74.7 s in Group 1. The mean cold ischemic time was 1204.25 ± 246.9 min in Group 2.

Twenty-five recipients had comorbid diseases, while four recipients did not. Comorbid diseases were more common in Group 1 (n = 17) compared to Group 2 (n = 8) (p = 0.021). The most common cause of ESRD was idiopathic (n: 14), the second was diabetes mellitus (DM) (n = 7). Hemodialysis was the most applied dialysis type before KT. The mean duration of pre-transplantation dialysis was significantly higher in Group 2 (130.4 ± 46.5 months) compared to that in Group 1 (22.07 ± 26.52 months) (p = 0.000) (Table 2). ECDs were preferred in 16 recipients, which was significantly higher in Group 2 (n = 11) compared to Group 1 (n = 5) (p = 0.001). DGF developed in 12 recipients, which was significantly higher in Group 2 (n = 9) compared to that in Group 1 (n = 3) (p = 0.006). Thirteen recipients in Group 1 and 10 recipients in Group 2 died with a functioning graft (DWFG). The difference was not statistically significant (p = 1.000). The female-to-male ratio of DWFG recipients was 6/17. This ratio was 2/11 and 4/6 in Group 1 and Group 2, respectively. The difference was statistically significant (p = 0.002). Only six patients, all of whom were female, returned to dialysis before death (p = 0.002). Four of them were in Group 1, and two patients were in Group 2 (p = 1.000) (Table 2).

About 52% of the deaths occurred within the 1st year of KT. Underlying causes of mortality were not different between the two groups (p = 0.407), with infection the leading cause (58.6%), followed by CVD (24.1%). Although infection-related mortality was higher within the 1st year, it was not statistically significant (p = 0.396). It was noteworthy that infection (n = 5) was the only cause of mortality within the first 2 months of KT. Malignancy developed only in the late period (> 1 year) (Table 3). Sepsis developed in 29.4% of infection-related deaths. COVID-19 constituted 23.5% of infection-related deaths. Two recipients in Group 1 and three recipients in Group 2 died from sepsis, while two recipients in Group 1 and two recipients in Group 2 died from COVID-19 infection. One recipient in Group 1 and two recipients in Group 2 died from bacterial pneumonia/sepsis. One recipient in Group 2 died from meningitis. One recipient in Group 2 died from invasive fungal infection (IFI) + Tbc. One recipient in Group 1 died from IFI. Two recipients in Group 1 died from viral infection (Table 4).

Table 3 The causes of death according to the both mortality by the time period post-transplantation and donor type

| Donor type | Mortality by the time period post-transplantation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 1 year (n = 15) | > 1 year (n = 14) | Total death (n = 29) | ||||

| Group 1 (n = 7) | Group 2 (n = 8) | Group 1 (n = 10) | Group 2 (n = 4) | Group 1 (n = 17) | Group 2 (n = 12) | |

| Causes of death | ||||||

| Infection/Sepsis | 4 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 9 |

| CVD | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 2 |

| CVA | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | 2 | 1 |

| Malignancy | - | - | 2 | - | 2 | 0 |

CVD: cardiovascular disease, CVA: cerebrovascular accident.

Table 4 Infectious causes of death according to the both mortality by the time period post-transplantation and donor type

| Donor type | Mortality by the time period post-transplantation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 1 year (n = 10) | > 1 year (n = 7) | Total death (n = 17) | ||||

| Group 1 (n = 4) | Group 2 (n = 6) | Group 1 (n = 4) | Group 2 (n = 3) | Group 1 (n = 8) | Group 2 (n = 9) | |

| Causes of death | ||||||

| Sepsis | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| COVID-19 infection | - | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Bacterial pneumonia/Sepsis | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Menengitis | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 |

| IFI+Tbc | - | 1 | - | - | - | 1 |

| IFI | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | - |

| Viral infections | 1 | - | 1 | - | 2 | - |

IFI: invasive fungal infection, Tbc: tuberculosis.

Both empirical and adjusted antimicrobial therapies were used during the peritransplant period in 59% (10/17) of the infection-related deaths, half of which were administered for donor-derived infections. They were used in 33.3% (4/12) of the non-infectious deaths, half of which were also administered for donor-derived infections.

Discussion

Despite the short-term increase in graft and patient survival, long-term outcomes are still not as expected4-12. The survival of kidney recipients is still shorter than that of the general population2. We evaluated the mortality after KT among kidney recipients, comparing several parameters. There was no statistical difference between two groups in terms of donor age, gender (both recipients and their donors) and mean follow-up time. However, the mean age of recipients in Group 2 was significantly higher than in Group 1, which might be attributed to the prolonged waiting period for DDKT. There is a serious organ shortage in our country as well as globally3. Patients have to wait for many years to be transplanted from deceased donors, which leads to an increase in the pre-transplantation dialysis period, as in the current study. As a result of this, the pre-transplantation dialysis period was longer in Group 2 than in Group 1.

Due to organ shortage, we perform KTs from ECDs, as with many transplant centers3. There are no universal criteria defining ECD. The current study shared the definition of ECD, which was applied and/or recommended by our clinic. Sixteen recipients (55.1%) had received kidney grafts from ECDs, the majority of whom were in Group 2. It was not surprising that the development of DGF was more common in Group 2, which included deceased donors. Mortality after KT, especially with a functioning graft, is still a serious problem2,4-6,8,9,11,12. Of all cases, 79.3% died with a functioning graft. DWFG was not associated with donor type. However, it was more common in male recipients, especially those who had received kidneys from living donors. This might be attributable to underlying health problems in males, irrespective of their grafts. Only six patients, all were female, returned to dialysis before death. Neither donor type nor donor gender affects the rate of return to dialysis. Female recipients had experienced higher graft loss.

Some authors have revealed that infection is the leading cause of mortality after KT, followed by gastrointestinal disease and CVD7,8. Others have reported that CVD is the most common cause of mortality and neoplasia the second9. Mazuecos et al. stated that infection was the most common cause of mortality within 1 year of KT, while CVD was the leading cause of mortality thereafter. They found that malignancy was the second common cause of mortality 1-year post-transplant6. According to the current study, causes of mortality after KT were similar to those in some studies, but not to those in others6-9. Almost over half of deaths occurred within the 1st year of KT and infection was the leading cause, which was followed by CVD in both groups. Not only recipient-derived microorganisms but also donor-derived microorganisms led to infections after KT. The current study showed that, in a developing country such as Turkey, infection continued to be a major cause of death after KT, both within the 1st year of transplantation and thereafter. This was a descriptive study without a comparator, and thus cannot be used to make conclusions on the efficacy and safety of immunosuppressive therapies. However, it was clear that infection was the only cause of mortality within the first 2 months of KT, in which immunosuppressive therapy was used intensively. Thus, modulation of immunosuppressive regimen and antimicrobial therapy according to supposed risk of recipient and donor-derived infections may be necessary. Optimization and standardization of donor management are also essential. It was noteworthy that mortality due to COVID-19, which has been present for the last year, constituted almost 25% of infection-related mortality after KT over 10 years.

Retrospective design and small case number were the limitations of the study. It was a descriptive research, and presented the characteristics of the kidney recipients, who had died. However, it did not reveal the underlying causes of mortality. While the findings from the current study were not evidence of causality, they helped to distinguish variables that might be important in explaining mortality after KT from those that were not. Thus, it can be used to generate hypotheses that should be tested using more rigorous designs, including immunosuppressive regimen, antimicrobial therapy, recipient and donor-derived infections.

Conclusion

To reduce mortality after KT, KT recipients should be encouraged to increase their preventive measures against infections, and they should be educated about lifestyle and dietary habits, especially in developing countries. Modulation of immunosuppressive regimen and antimicrobial therapy according to supposed risk of recipient and donor-derived infections and early diagnosis and treatment of CVD is also important in decreasing mortality in KT recipients.

Within a relatively brief period of time, the current COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a significant proportion of infection-related mortality after KT. As in the management of other infectious diseases, a multidisciplinary approach should be implemented in the management of COVID-19 infection.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)