Background

Venous Thrombosis (VT) is the medical term for a clot formed within the venous vascular network; it is a common disorder that frequently appears in the lower extremities, affecting mainly the superficial and deep veins1-3.

Superficial Venous Thrombosis (SVT), also called superficial thrombophlebitis, is a common pathology, in which inflammatory and prothrombotic factors affect a superficial vein4. The Saphenous vein is the most affected, approximately 60-80% of the SVT occur within the greater saphenous vein, and 10-20% in the minor saphenous vein5,6.

Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) refers to the formation of clots within the deep veins, which are satellite-related to an artery. This pathology mainly affects the deep veins of the lower extremities, such as the femoral or popliteal vein3,7. Another frequent form of presentation is pulmonary embolism (PE). It rarely manifests itself elsewhere (i.e., upper limbs, liver, brain sinus, retina or mesenterium)1,3.

The global prevalence of DVT is 100 people per 100,000 inhabitants per year. The incidence of DVT and its recurrence is higher in men than in women. However, due to the risk factors associated with reproduction (i.e., pregnancy, puerperium, and oral contraceptives) the rates are higher in young women2. Likewise, it has been identified more frequently in the African-American and Hispanic ethnic communities than in the Caucasian8.

SVT is two to four times more frequent than venous thromboembolic disease (VTE). The former, has an incidence of 3-11%, and even though its prevalence has not been well established, some studies estimate that it appears in up to 1% of the population, and in patients with varicose veins the prevalence is 4-59%. The average age of presentation of SVT is the sixth decade of life, and it mainly affects the female gender9,10.

Venous thrombosis is a common pathology that affects patients both as a result of hospital internment and otherwise11. The etiology of the VT subtypes is clearly related, they share the same risk factors and the origin of both can be both hereditary and/or acquired6,12. However, SVT and DVT are frequently found simultaneously13. This is because patients who present VT have the particular characteristic of having the three components of Virchow’s triad: (a) impairment in blood flow such as stasis, (b) acquired or inherited hypercoagulability (c) vascular endothelial injuries14-16.

Over time, SVT has been recognized as a self - limited benign pathology, as it is mostly local and non-systemic implications, and to the fact that it can be managed effectively with no invasive measures17,18.

However, recent evidences suggest that recurrence may not be that infrequent and has raced new questions about the factors that may increase the odds for recurrence, in consequence recurrence may also increase the probability for a DVT or PE event around the time of diagnosis10,19,20. DVT and PE constitute the two main variants of VTE, which are associated to both morbidity and mortality21.

VT incidence depends on demographic factors such as population aging comorbidities distribution and associated with venous thromboembolism and environmental aspects that may affect thombolism frequency in a certain population, such as obesity, heart failure and cancer; as well as improved sensitivity of imaging tests used to detect VTE and the now widespread use of such tests22.

During youth, a lower risk due to the capacity for the formation of anti-thrombin and alpha 2 -macroglobulin, as well as a lower production of thrombin has been reported8. As age is an important risk indicator for developing VT and for undergoing adverse outcomes since there is a higher incidence in the later stages of life, mainly from the age of 50 onwards in the case of DVT, and from 60 years in the case of SVT3,23.

Patients in need of orthopedic or pelvic surgery (trauma, urological or gynecological), constitute one of the groups with the highest risk of developing a DVT episode. Within this group, the incidence of this pathology ranges between 40-60% in patients without prophylaxis24. Any procedure involving the venous wall may act as predisposing factor for SVT9.

Less frequent predisposing risk factors for VT are immobilization, hospitalization, trauma, pregnancy, postpartum, hormonal therapy, hereditary or acquired hypercoagulable states, myocardial infarction, infections, inflammatory bowel disease, and kidney disease4,8.

Early approach of VT is key to prevent acute complications such as PE (15-32%), long-term complications such as post-phlebitic syndrome and pulmonary hypertension, as well as to avoid recurrence within 12 months (10%)7,25. A common obstacle to early diagnosis is the frequent asymptomatic presentation of DVT. Occasionally, the presence of edema, erythema and pain from the affected anatomical part, can help to timely identify a possible episode.25 Diagnosis can be established using clinical scores, determination of the D-dimer and imaging studies; even when angiography is considered the gold standard, ultrasound can also orient the diagnosis of VT3,5,25,26.

Considering the frequency of development and the prevalence of VT and similar interrelated conditions amongst the Mexican population, and the recent advances in therapeutic and diagnostic strategies, there is very little information available on the Mexican population.

Mexico as many other countries is undergoing an increase in life expectancy which means having a growing elderly population. Mexican population is characterized by having high prevalence of chronic disease in adult population that may increase the odds of developing VT. Therefore, knowing and analyzing the mobility and mortality trends due to TV is pertinent for preventing, clinical and even administrative purposes.

For this reason, the aim of the present study is to describe hospital mobility and mortality for superficial, deep and nonspecific venous thrombosis of the lower limbs in Mexico between 2016 and 2018.

Material and Methods

The present is an observational and retrospective study based Mexican hospitalized patients diagnosed with the primary diagnosis of venous thrombosis of the lower limbs (VTLL). The information was obtained from the public hospitals provided by the General Directorate of Health Information (DGIS)27,28.

The main condition, defined as the primary cause that originated the need for treatment for the patient whose discharge is included in the database, uses the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Health-Related Problems, Tenth Review (ICD-10). For the purposes of this study, the code “I” with numeral 800-803 was used, which corresponds to phlebitis and thrombophlebitis of superficial vessels, of the femoral vein, and other deep and nonspecific vessels of the lower limbs29.

All Mexican patients from public hospitals in Mexico in the period between January 1, 2016 through December 31, 2018, which were diagnosed with thrombotic diseases (phlebitis and thrombophlebitis) of the veins of the lower limbs. Therefore, excluding those patients whose initial diagnosis was not “I” 800 – 803.

The information derived from hospital includes the date of admission and discharge, the sociodemographic data of the patient, the days of hospital stay, the reason for discharge (including deceased patient and non-deceased patient), main disease during the hospital stay, and infections27,28.

All mentioned variables were considered as binary, except for age, length of hospital stay and residence of the hospitalized.

Statistic analysis

for descriptive statistics, the frequencies of the variables were generally represented. Regarding the categorical variables, they were described as proportions raised to percentages with their respective observed numbers. As for the numerical variables of hospital discharges, they were represented by measures of central tendency (means) and measures of dispersion (the standard error (ES) corresponding to the mean used as well as the standard deviation (ED) with confidence intervals (95% CI).

For the comparison of the obtained data, one-tailed hypothesis contrast tests were used. For the categorical variables, the two-sample proportions test was used for the variable of female and male gender of the hospitalized patient as a grouping variable for mortality. For the numerical variables of age and days of hospital stay, the two-sample mean contrast test was used, using hospital mortality as the grouping variable. A p value of <0.050 and a 95% CI were taken for statistical significance regarding the differences in the means and proportions obtained in the study. Likewise, for the association of variables, the linear regression model was used taking the days of hospital stay as a dependent variable, and age and death as independent variables. The statistical data was processed using the Stata 14® program. The results obtained were represented as figures and tables.

For the epidemiological description, the following frequency was established:

a) Hospital mortality rate by state, which was obtained by dividing the numerator (total deaths from VTLL in patients hospitalized in a given state during the period observed) multiplied by 1,000 between the denominator (total hospital discharges by VTLL in Mexico during the period observed).

b) Rate of hospitalizations by state: it is the quotient of the number of patients discharged with the main diagnosis of VTLL in a given state, multiplied by one hundred thousand, and divided by the population mid-year in the studied period

Results

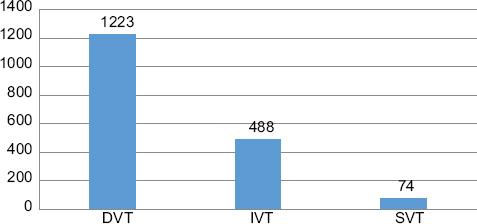

Nationwide, the total number of patients hospitalized for DVT, SVT and IVT of the lower limb was 1,785 between 2016 and 2018.

The most frequent form of VTLL during the three years, was DVT with 1223 cases (69%), followed by IVT with 488 cases (27%), and SVT with 74 cases (4%) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 Number of hospitalized and discharged patients with the diagnosis of DVT, SVT and IVT of lower limbs in Mexico during the years 2016 to 2018. n = 1785.

All VTLL reported a higher presence in females with 1109 (62%) cases compared to males with 676 (38%) cases. Presenting a female: male ratio of 1.64 (Table 1).

Table 1 Epidemiological variables of DVT and SVT in Mexico during the years 2016 to 2018 (n = 1785)

| Variables | DVT | % DVT | SVT | % SVT | Total VTLL cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 475 | 38.83% | 18 | 24.32% | 676 |

| Female | 750 | 61.32% | 56 | 75.67% | 1109 |

| First presentation | 1059 | 86.59% | 69 | 93.24% | 1059 |

| Recurrence | 164 | 13.40% | 4 | 5.40% | 191 |

| Infection | 10 | 0.81% | 0 | - | 19 |

| Average days of hospitalization | 6 | - | 4 | - | - |

| Average age | 53 | - | 44 | - | - |

| Mortality | 38 | 2.12% | 0 | - | 47 |

* VTLL: venous thrombosis of the lower limbs, DVT: deep vein thrombosis, SVT: superficial vein thrombosis.

* Results are expressed in number and percentage.

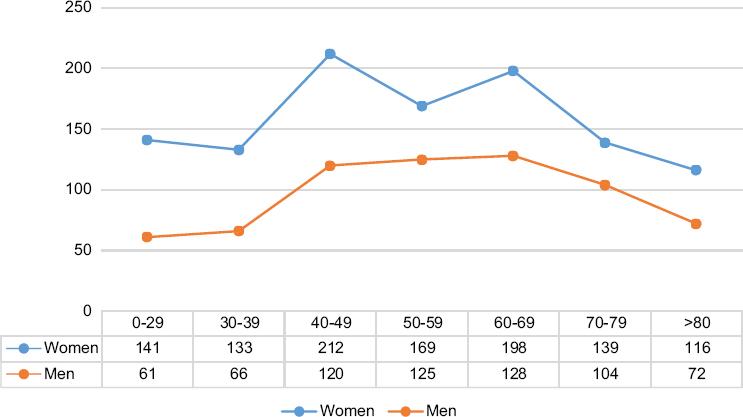

The mean age of all patients hospitalized for VTLL was 54 years (53 years in women and 55 years in men). However, the mean age was different for each type of thrombosis, being higher in patients with DVT (mean age of 53 years) compared to patients with DVT (mean age of 44 years). The presentation of VTLL by age is presented in figure 2 (Table 2).

Figure 2 Distribution of cases of VTLL by age and sex in Mexico during the years 2016 to 2018. n = 1785.

Table 2 Epidemiological variables of VTLL according to gender in the Mexican population during the years 2016 to 2018

| Variables | Men | % Men | Women | % Women | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VTLL | 676 | 38% | 1109 | 62% | 1785 |

| DVT | 474 | 39% | 749 | 61% | 1223 |

| SVT | 18 | 24% | 56 | 76% | 74 |

| IVT | 184 | 38% | 304 | 62% | 488 |

| Average age | 55 | - | 53 | - | - |

| Average days of hospitalization | 6.91 | - | 5.59 | - | - |

| In-hospital infection | 9 | 47% | 10 | 53% | 19 |

| Recurrence | 71 | 37% | 120 | 63% | 191 |

| Mortality | 25 | 53% | 22 | 47% | 47 |

*VTLL: venous thrombosis of the lower limbs, DVT: deep vein thrombosis, SVT: superficial venous thrombosis, IVT: nonspecific venous thrombosis.

*Results are expressed in number and percentage.

The national average incidence of hospitalization was 1.40 per 100, 000; there was a certain variation by federal entity. The states of the Mexican Republic with the highest hospitalization rate were Guanajuato with 4.46, Aguascalientes with 3.20, Baja California Sur with 2.48, Jalisco with 2.25, and Veracruz with 2.27 per 100,000 people during the years 2016 to 2018. The rate of hospitalization by state is presented in figure 3.

The average number of days of hospital stay was higher in the patients with the diagnosis of DVT, compared with the patients with SVT (mean of 6 and 4 days respectively) (Table 1).

Most of the patients belonged in the initial presentation category with a total of 1,593 cases (1059 cases in DVT and 69 cases in SVT). The number of patients that belonged in the recurrent presentation category was lower, with a total of 191 cases (164 cases in DVT and 4 cases in SVT) (Table 1).

Ninety percent of the patients were discharged with a diagnosis of clinical improvement. However, 47 deaths were registered, of which 38 were from DVT and nine from DVI; resulting in a hospital mortality rate of 26 cases per 1000 patients (Table 1).

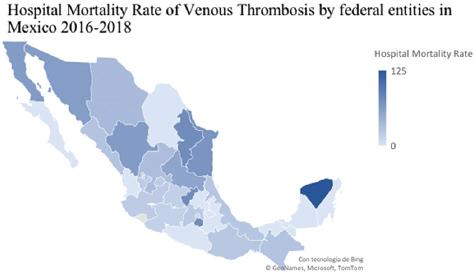

At the national level, the states with the highest hospital mortality were Yucatan, with a rate of 125, followed by Morelos, Nuevo León and Querétaro with 77, and Tamaulipas with 70 (mortality rate per 1000 hospitalized patients) (Fig. 4).

In relation to the deceased patients, two (4.25%) of those diagnosed with DVT presented an infection. Most of the diseased patients presented DVT and DVI for the first time (34 patients and nine patients respectively), and four of the diseased patients had a recurrent presentation, all of them in the DVT diagnosis category.

Using the proportions comparison test, it was identified that mortality in men (53%) is higher than in women (46%) (95% CI, p <0.05) (Table 2).

In the mean comparison test, it was obtained as a statistically significant result that, as patient age and hospital stay increase, there is a higher probability of mortality; deceased patients had an average age of 65, and an average hospital stay of ten days. Non-deceased patients had an average age of 53, and an average of hospital stay of five days (95% CI, p <0.05).

In the linear regression test, it was obtained that regardless of the age of the patient, the mortality rate is related to the number of days of hospital stay; the greater the number of days, there is a 4.38 times greater risk of death (95% CI, 2.46-6.31).

Discussion

We have described the incidence of TVLL in Mexico, the hospitalization rates differ between federal entities and some variables were different compared to other studies.

The state of the Mexican republic with the highest hospitalization rate was Guanajuato with 4.46 per 100 000 habitants, however Yucatan was the state with the highest mortality rate (125 per 1000 hospitalized patients).

In the reviewed literature, it is estimated that SVT is two to four times more frequent than DVT. Although, in this study, most of the patients had DVT (69%) compared to SVT (4%). A history of SVT has been identified to result in a six-fold increased risk of DVT, and at the time of diagnosis approximately 25% of patients with SVT have a concomitant VTE disease (23.4% DVT and 3.9% PE). In this review we did not describe patients with this simultaneous presentation9,19,20.

During the years 2016-2018 covered in this study, it was observed that the majority of cases of VTLL occurred in the female sex (62%). In the case of SVT, this proportion is even higher (76%). The incidence rate of DVT differs according to the age range, it is higher in women during the reproductive stage (16-44 years), while after 45 years of age, the disease is more common in men27. This can be explained by the already known correlation with certain risk factors related to women, such as pregnancy, consumption of hormonal therapy and contraceptives. Pregnant women are at higher risk of VTLL than non-pregnant women of similar age7.

Mortality rates increase markedly with age. As age increases, there is a greater risk of immobility and comorbidities, and also a decrease in muscle tone and aging of the veins, particularly in the valves2. In this study, the mean age of all patients hospitalized for VTLL was 54 years; specifically in women was 53 (close to the onset of menopause), which may be related to hormonal therapy used as menopause treatment, since it increases the risk of developing VTE from two to four times. However, the average age in patients with SVT was 44 years, which contrasts with other studies reporting an average age of 60 years at the time of diagnosis9.

The total number of recurrent cases of VTLL were 191 (10%), of which 164 (9%) were due to DVT. Duffet et al, analyzed the recurrence rate in patients with VTE, which was 10% in one year and 30% in 5 years.4 VTE recurrence can be related to multiple factors. Patients who receive anticoagulant treatment for less than three months have a higher recurrence rate during the first six months after the initial event; the decision to prolong anticoagulation depends not only on the risk of recurrence, but also on the bleeding risk. Male sex has also been shown to be an independent predictor of recurrence. However, the recurrence percentage in the studied patients was the same in men and women (10%), taking as 100% the total number of cases according to gender30-32.

In recent years, risk stratification and treatment protocols have been implemented in patients with VTE, which has generated a better choice between outpatient and in-hospital management. 30 It has been studied that prolonging days of hospital stay increases costs, the use of medical services, and the risk of complications, such as infections and pressure ulcers; otherwise, decreasing days of hospital stay and the use of more effective therapies, such as oral anticoagulants and local thrombolysis, have been documented to have contributed to a significant reduction in mortality33-35.

In this study, it was observed that the patients who died had an average of ten days of hospital stay, and in the non-deceased patients, the average was five days, so the probability of mortality from VTLL increases as the days of hospital stay. And the death of patients in whom active infection was reported (4.25%) occurred exclusively in patients diagnosed with DVT. Various epidemiological studies have investigated the effect of infection on VT events, it has been established as an acute precipitating or triggering factor. The proposed mechanisms include the activation of the inflammatory, coagulation and fibrinolysis processes associated with thrombosis36-39.

Current evidence recommends outpatient treatment in the hospital setting in those patients at low risk and with the appropriate circumstances at home to comply with the treatment; this helps prevent exposure to nosocomial infections and contributes to increased availability of hospital beds and reduced costs. On the other hand, outpatient treatment promotes better mobility and well-being of patients, thus reducing the risk factor of physical inactivity33-35.

The prognostic tools such as the Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index (PESI) or the Geneva Criteria, and also the treatment with low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) and the new non-vitamin K-dependent oral anticoagulants (NACO), offer advantages in providing outpatient treatment33,40.

Conclusion

Hospitalization due to VTLL is more frequent in deep veins than in superficial and nonspecific veins; it mainly affects women, however mortality is higher in men. The longer hospital stay is an important mortality factor in patients with VTLL. This statistical report is the first to report the epidemiology of venous thrombosis in Mexico for more than ten years.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)