Introduction

Diffuse cavernous hemangioma (DCH) is an uncommon disease. It is grouped with the benign vascular malformations of the gastrointestinal tract and it is considered as a progressive intestinal hamartoma. That means a border lesion between malformations and tumors1. The rectosigmoid is the most common site of location and recurrent rectal bleeding is the most frequent symptom. DCH is often misdiagnosed due to lack of knowledge of its clinical features. The diagnosis is usually established on endoscopic characteristics although imaging studies play an important role. Surgery is the recommended treatment.

Case report

We present a 34-year-old man who presents recurrent episodes of rectal bleeding since the childhood. He was diagnosed at age of 15 of DCH of the rectosigmoid colon and a sigmoidectomy was performed. After this, rectal bleeding persisted and the patient was misdiagnosed of Grade IV hemorrhoids in successive colonoscopies. He has no other symptoms such as abdominal pain or fever. However, he became severely anemic with frequent episodes of recurrent rectal bleeding and required several blood transfusions before being referred to our hospital.

Physical examination revealed a soft and circumferential mass palpable from the anal verge. The laboratory test confirmed a ferropenic anemia. A plain abdominal X-ray showed multiple phlebolites in the pelvis. Following another episode of rectal bleeding, an arteriography was carried out. A large perirectal vascular network containing dilated vessels was visible although no pooling was found. An MRI showed a rectal mass of 12 × 10 cm in size affecting the anal canal. Very high signal intensity on T2 images and multiple engorged vessels in the perirectal fat were also seen (Fig. 1). As a recurrent DCH of the rectum was suspected, a surgical procedure was suggested to the patient.

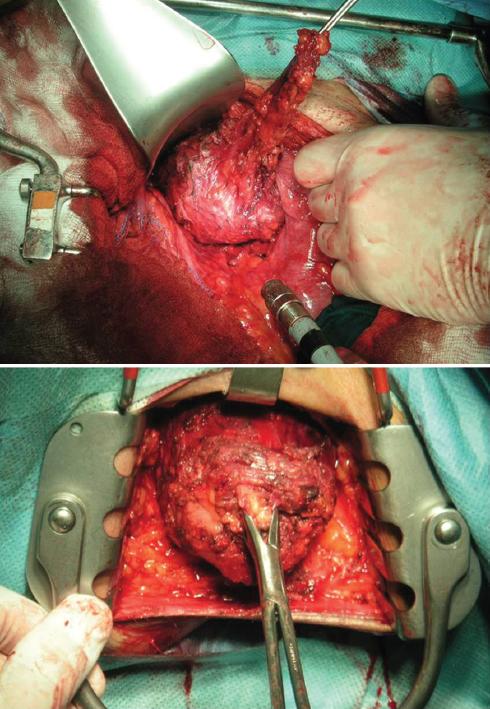

An APR was performed as the tumor extended into the canal anal with sphincter involvement (Fig. 2). The macroscopic view of the rectum showed abnormal hemangiomatous vessels affecting the dentate line (Fig. 3-4). Histological examination demonstrated a DCH invading all layers of the rectum. The patient was discharged on post-operative day seven and at 2 years follow-up, the patient was free of symptoms and without endoscopic and radiologic recurrence.

Discussion

Gastrointestinal angiomas have an incidence of 0.3% and represent about 3–10% of all benign intestinal tumors1,2. Gastrointestinal angiomas can be divided into five categories according to Pholen1: Phlebectasias, cavernous hemangioma, diffuse infiltrating cavernous hemangioma, polypoidal cavernous hemangioma, and capillary hemangioma. The DCH is considered as a progressive intestinal hamartoma, a border lesion between malformations and tumors.

DCH of the large intestine is a rare benign vascular lesion that was first described in 1839 by Philips and it usually affects the rectum and sigmoid colon3. The most common symptom is painless recurrent rectal bleeding. Sometimes, it appears as massive hemorrhage which is occasionally life threatening. Others, anemia is the only complaint because of occult bleeding2-4. Our case is an example of a typical presentation because of the rectal bleeding and the anemia. Obstruction may be present in 20% of the patients and about 10% of patients with DCH have no symptoms5.

It often begins early in life and may mimic a variety of diseases. Usually, its symptoms are attributed to internal hemorrhoids, polyps, ulcerative colitis, or even though a neoplasm4. Furthermore, a high percentage of patients have a previous surgical history especially a hemorrhoidectomy such as in our case report. Jeffrey et al. reported that 80% of patients had undergone at least one inappropriate surgical procedure because of an incorrect diagnosis6.

The need of an early and correct diagnosis has been underlined in the most of literature about management of these lesions. Also it is very important to recognize the exact extension of the DCH because a failure on this may lead to insufficient surgical resection and what is more, this may lead to a recurrence of the symptoms as happened in our patient.

Definitive diagnosis is usually made by a rectoscopy or colonoscopy. Blue nodular lesions are typical findings. It represents submucosal veins, which are dilated and engorged. Because of a high hemorrhage risk, a biopsy in patients with suspect of DCH should be avoided3,4-7.

The diagnosis can be suspected if extensive pelvic phleboliths are found on a plain abdominal X-ray, seen in 26-50% of cases. Those phleboliths are rare in patients under the age of 40 and typically appear in a central position, which is an unusual location. These two characteristics are an important clue to the diagnosis. They are secondary to venous thrombosis within the tumor, caused by perivascular inflammation and stasis of blood flow3,7,8.

Barium enema shows only unspecific signs such as narrowing of the rectum, mucosal irregularity, or polypoid lesions3.

A CT scan provides accurate diagnosis demonstrating rectal wall thickening, vascular engorgement, and multiple intramural calcified phleboliths. In addition, it is useful to plan the intervention as shows extent of lesion and adjacent organs involvement2,3,7. However, the MRI is the preferred diagnostic method. MRI shows typical heterogeneous bright signal intensity in T2 images and an intermediate signal intensity in T1 images. A thickened rectosigmoid wall with very high signal intensity in T2 images is also visible and the vascular network of the DCH is seen as serpiginous structures as showed the MRI of our patient. Because of these specific findings, multiplanar capability and high resolution after injection of gadolinium contrast MRI are the imaging modality of choice in the pre-operative staging. It also helps to assess the extent of invasion into the anal canal and sphincter involvement, especially when an endorectal surface coil is available. Endorectal ultrasound provides similar information and is useful in demonstrating the layers affection of the rectal wall as does endorectal MRI2,7,8.

Elective treatment should be recommended once the diagnostic has been established. Non-operative techniques such as sclerotherapy, cryotherapy, or argon fulguration have been used. These procedures are only suitable for well-defined and small lesions3,9,10, otherwise, the bleeding will recur. Angiography and embolization can be useful in cases of acute bleeding; however, pooling is not always visible and recurrence is also the rule1,4. The only treatment that controls the bleeding is the complete surgical resection. If it is technically feasible, a sphincter saving procedure with anterior rectal resection and coloanal anastomosis is the preferred treatment. Because of extracolonic organ can be affected, a good exploration of the abdominal cavity should be performed2.

When the tumor extents into the anal canal involving sphincters, an APR is the best curative procedure, even though a permanent colostomy is undesirable, especially in young patients3,7. In our patient, the dentate line was affected by the DCH and an APR was considered the most appropriate procedure. The patient agreed although the inconvenient of the ostomy as he have had several life-threatening bleeding episodes. A laparotomy was performed in this case even though it is also feasible a laparoscopic procedure. Others preferred transanal endoscopic surgery11,12. The option of a complete resection by the pull-through transection and coloanal anastomosis can be performed if anal canal is not involved13. This procedure was first proposed in 1976 and now is also successfully performed laparoscopically. This has the benefit of resecting the DCH without permanent stoma formation, as would be the case with abdominoperineal resection6,13,14.

Some authors do not remove all the hemangiomatous tissue and only remove the engorged friable rectal mucosa that constitutes the primary site of rectal bleeding. For those authors, the vascular malformations that might be in the bowel wall distal to the dentate line can be treated conservatively3. This allows to performed sphincter saving procedures. Although this seems to be a valid option and many publications considered it as the best one if technically feasible, we preferred to ensure the complete resolution of the bleeding and excided the whole tumor and so preferred the patient even though the need of permanent colostomy. Cotzias et al. have successfully managed conservatively with tranexamic acid avoiding the need for resection a DCH of the sigmoid and rectum15.

In conclusion, DCH is a rare condition that causes rectal bleeding. It should be considered in cases of long history of recurrent and painless rectal bleeding. DCH is often misdiagnosed due to its symptoms are attributed to common anorectal pathologies. The diagnosis is established on endoscopy although MRI with gadolinium contrast is the preferred diagnostic method. If possible, a sphincter saving procedure with compete resection of the DCH is reliable method of treatment. However, when sphincters are involved, an APR may be necessary.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)