Introduction

Maxillofacial traumas (MFT) and more specific fractures can be considered as consequential conditions as they may result in mortality, severe morbidity, facial disfigurement, and functional limitations1,2. Early diagnosis of MFT is thus essential not only to detect concomitant injuries and emergent complications, but also to plan the reconstruction of functional areas.

The epidemiology of MFT varies between populations, it costumes and other demographics matters1,3. Injuries caused by traffic, domestic, and work accidents are some causes that provoke MFT, and firsts constitute an important public health problem, since they are the eighth cause of death in the world, especially in the young population between 15 and 29 years of age2,4. Further, MFT are among the most common cause of presentations in an emergency department1.

MFT can affect the patient's ability to eat, speak, and interact5 hence the importance, once the trauma has occurred, to restore the patient's normal functions in a timely and adequate manner. However, to achieve this, it is important to know how these traumas are specifically developed in the regions and localities where the appropriate services are provided to treat these ailments.

The patterns of MFT have been studied in different countries, such as Colombia2, Brazil3,6, Chile7, China8,9, United States10, Ethiopia11, India12-15, Iran16, Mexico17, Malaysia18, Nigeria19, United Kingdom20, Sudan21, and Romania22. However, few published Cuban articles are available analyzing the epidemiology and management of MF fractures in general23-26. This fact enhances the importance of this research.

Maxillofacial injury poses a challenge to oral and maxillofacial surgeons working in developing countries with limited resource and human power11. Maxillofacial treatment depends on the pattern and severity of the trauma and may be conservatively with debridement and suture, closed reduction with arch bar or eyelets, or surgically with open reduction using titanium mini plates. Procedures with open reduction resulted satisfactory facial esthetic, shortened duration of work absence, and preserves function early and reduced the incidence of complications13. Due to anteriorly raised, this article aims to characterize the maxillofacial fractures surgically treated in a Cuban hospital.

Materials and methods

The present study involved a 3-year descriptive, and retrospective cross-sectional study in patients with maxillofacial fractures who were surgically treated (open surgical treatment or open reduction and internal fixation) in the Maxillofacial Surgery Department of Carlos Manuel de Céspedes General University Hospital, Bayamo, Granma, Cuba. This hospital is responsible for the secondary care of patients from the capital and other six municipalities of the Granma Province. However, patients from other municipalities with neurosurgical issues are attended too because the unique Neurosurgery Department of the province is located at this hospital. The time period was from January 1, 2017 to December 31, 2019.

The study inclusion criteria were: (a) patients of both sexes and all age groups; (b) a history of an acute trauma episode; (c) X-ray or computed tomography confirming the clinical diagnosis of fracture and evidencing its location and characteristics (with or without contiguous bodily fractures/injuries); (d) surgical treatment of the fracture performed in the study host institution; and (e) signing of an informed consent by all patients, through which they agreed to the use of their medical data for scientific research. Patients with incomplete medical records or with unclear data were excluded from the study. During these 3 years, 132 patients with maxillofacial fractures were treated in our department. However, six cases had unclear/incomplete record and were excluded from the study.

Data were collected by the principal investigator using predesigned templates. The data collected from the patient's record were: age, gender, residency (urban/rural), municipality, etiology, month and year of trauma, number of fractures, the topographic location of the fracture (zygomatico-maxillary complex, mandible, Le Fort I, Le Fort II, Le Fort III, pan facial, orbital floor, and naso-orbito-etmoidal), and alcohol consumption at the time of trauma (yes/no). The etiology of trauma was divided into five main categories: (a) interpersonal violence (IPV); (b) animal attacks; (c) accidents, which include road traffic, sport, bike and job; (d) fall; and (e) complicated extractions. The patients' age ranged from 13 to 84 years, and they were divided into four age groups: younger than 20 years, 21 to 40, 41 to 60, and older than 61 years. Alcohol consumption information collected was based on medical record. Mandibular fractures included fractures of the symphysis, parasymphysis, body, angle, ramus, coronoid, and condyle.

This research is in accordance with all ethical standards. The Scientific Ethics Committee of the hospital approved the project. The ethical committee also provided permission to review the medical records of the patients.

Descriptive statistics was performed with a two decimal percentage accuracy. Continuous data were expressed as mean and standard deviation, and nominal data were expressed as frequency and percentage. The raw (bivariate) and adjusted (multivariate) associations according to alcohol consumption were calculated. To obtain raw and adjusted prevalence ratio, generalized linear models, with the use of the Poisson family, log linkage function, and thick models, were constructed and adjusted by setting municipalities as a cluster group. The statistical analysis was elaborated in Stata version 11.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), and p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

As shown in table 1, in 126 patients treated surgically, 304 maxillofacial fractures were found (approximately two fractures per patient). A greater proportion of injured patients were males (115) compared with females (11) resulting in a ratio of 10.45:1. The age of patients at the time of injury ranged from 13 to 84 years, with a mean age of 39.99 (± 14.62) years. The commonest age groups were 21-40 and 41-60 reporting 52 cases (41.27%), respectively. When disaggregated by residency, the highest frequency was observed in male urban patients (90.77%).

Table 1 Distribution of patients according to socio-demographic characteristics

| Socio-demographic characteristics | Patients | Gender | Fractures | Ratio fracture: patient | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | ||||||||

| n | %* | n | % | n | % | n | %** | ||

| Age groups | |||||||||

| ≤20 | 11 | 8.73 | 11 | 100 | 0 | - | 26 | 8.55 | 2.36 |

| 21-40 | 52 | 41.27 | 46 | 88.46 | 6 | 11.54 | 119 | 39.14 | 2.29 |

| 41-60 | 52 | 41.27 | 49 | 94.23 | 3 | 5.77 | 129 | 42.43 | 2.48 |

| ≥ 61 | 11 | 8.73 | 9 | 81.82 | 2 | 18.18 | 30 | 9.87 | 2.73 |

| Residency | |||||||||

| Rural | 61 | 48.41 | 56 | 91.80 | 5 | 8.20 | 149 | 49.01 | 2.44 |

| Urban | 65 | 51.59 | 59 | 90.77 | 6 | 9.23 | 155 | 50.99 | 2.54 |

| Fractures per patient | |||||||||

| 1 | 24 | 19.05 | 20 | 83.33 | 4 | 16.67 | 24 | 7.89 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 50 | 39.68 | 48 | 96.00 | 2 | 4.00 | 100 | 32.89 | 2.00 |

| 3 | 35 | 27.78 | 32 | 91.43 | 3 | 8.57 | 105 | 34.54 | 3.00 |

| 4 | 13 | 10.32 | 11 | 84.62 | 2 | 15.38 | 52 | 17.11 | 4.00 |

| ≥5 | 4 | 3.17 | 4 | 100 | 0 | - | 23 | 7.57 | 5.75 |

| Years | |||||||||

| 2017 | 42 | 33.33 | 37 | 88.06 | 5 | 14.29 | 92 | 30.26 | 2.19 |

| 2018 | 34 | 26.98 | 34 | 100 | 0 | - | 83 | 27.30 | 2.44 |

| 2019 | 50 | 39.68 | 44 | 88.00 | 6 | 12.00 | 129 | 42.43 | 2.58 |

| Total | 126 | 100 | 115 | 91.27 | 11 | 8.73 | 304 | 100 | 2.41 |

The distribution of the patients according to municipalities is the following: Bayamo (n = 59), Jiguaní (n = 15), Guisa (n = 13), Buey Arriba (n = 13), Cauto Cristo (n = 10), Río Cauto (n = 9), Manzanillo (n = 4), Campechuela (n = 1), Bartolomé Masó (n = 1), and Yara (n = 1). As shown in table 2, alcohol consumption was recorded in 46.83% of the patients, mainly in males (n = 56), as well as those aged ≤ 40 years (n = 30). In 36 rural patient alcohol consumption before the incidence of the trauma was recorded.

Table 2 Association between alcohol consumption and maxillofacial fractures incidence

| Socio-demographic characteristics | Total | Maxillofacial fractures | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol consumption | No alcohol | ||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 115 | 56 | 48.70 | 59 | 51.30 |

| Female | 11 | 3 | 27.27 | 8 | 72.73 |

| Age | |||||

| ≤ 40 | 63 | 30 | 47.62 | 33 | 52.38 |

| ≥ 41 | 63 | 29 | 46.03 | 34 | 53.97 |

| Residency | |||||

| Rural | 61 | 36 | 59.02 | 25 | 40.98 |

| Urban | 65 | 23 | 35.38 | 42 | 64.62 |

| Fractures per patient | |||||

| ≤ 2 | 74 | 36 | 48.65 | 38 | 51.35 |

| ≥3 | 52 | 23 | 44.23 | 29 | 55.77 |

| Total (n = 126) | 59 | 46.83 | 67 | 53.17 | |

In the bivaried analysis, alcohol consumption was significantly lower as the age increased (p = 0.047), in urban patients (p = 0.001), and it was higher in the left side fractures (p = 0.042). In the multivariate analysis, taking into consideration this three variable of the bivariate associations, alcohol consumption was significantly lower as the age increased (aPR: 0.989; confidence interval [CI] 95%: 0.979-0.99; p = 0.026), as well as in those patients who lived in urban zones (aPR: 0.57; CI 95%: 0.44-0.74; p < 0.001), adjusted by the side of the fracture and the municipality.

IPV was found to be the paramount etiological factor for maxillofacial fractures (46.03%), followed by road traffic accident (RTA) (17.46%). Animals attacks, bike-related accidents, and falls had equal contribution (n = 12; 9.52%, respectively). Patients aged ≤ 40 years were mainly affected by IPV (n = 32; 50.79%). RTA-related fractures were commonest in male patients (n = 21; 18.26%) as well as in those aged ≥ 41 years (n = 15; 23.81%). In rural patients, 54.10% and 13.11% cases were due to IPV and animal attacks, respectively. Only two maxillofacial fractures (mandibular angle) were due to complicated teeth extractions (Table 3).

Table 3 Etiology of maxillofacial fractures in relation to socio-demographic variables

| Variables | Etiology n (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interpersonal violence | Animal attacks | Accidents | Falls | Complicated extraction | ||||

| Road traffic | Sport | Job | Bike | |||||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male (n = 115) | 52 (45.22) | 12 (10.43) | 21 (18.26) | 5 (4.35) | 3 (2.61) | 11 (9.57) | 9 (7.83) | 2 (1.74) |

| Female (n = 11) | 6 (54.55) | - | 1 (9.09) | - | - | 1 (9.09) | 3 (27.27) | - |

| Age | ||||||||

| ≤40 (n = 63) | 32 (50.79) | 7 (11.11) | 7 (11.11) | 5 (7.94) | 2 (3.17) | 6 (9.52) | 4 (6.35) | - |

| ≥ 41 (n = 63) | 26 (41.27) | 5 (7.94) | 15 (23.81) | - | 1 (1.59) | 6 (9.52) | 8 (12.70) | 2 (3.17) |

| Residency | ||||||||

| Rural (n = 61) | 33 (54.10) | 8 (13.11) | 7 (11.48) | 1 (1.64) | - | 6 (9.84) | 6 (9.84) | - |

| Urban (n = 65) | 25 (38.46) | 4 (6.15) | 15 (23.08) | 4 (6.15) | 3 (4.62) | 6 (9.23) | 6 (9.23) | 2 (3.08) |

| Number of fractures per patient | ||||||||

| ≤2 (n = 74) | 38 (51.35) | 7 (9.46) | 8 (10.81) | 2 (2.70) | 3 (4.05) | 7 (9.46) | 7 (9.46) | 2 (2.70) |

| ≥3 (n = 52) | 20 (38.46) | 5 (9.62) | 14 (26.92) | 3 (5.77) | - | 5 (9.62) | 5 (9.62) | - |

| Years | ||||||||

| 2017 (n = 42) | 17 (40.48) | 4 (9.52) | 7 (16.67) | 3 (7.14) | 1 (2.38) | 6 (14.29) | 2 (4.76) | 2 (4.76) |

| 2018 (n = 34) | 16 (47.06) | 3 (8.82) | 8 (23.53) | 2 (5.88) | 2 (5.88) | 2 (5.88) | 1 (2.94) | - |

| 2019 (n = 50) | 25 (50.00) | 5 (10.00) | 7 (14.00) | - | - | 4 (8.00) | 9 (18.00) | - |

| Total patients (n = 126) | 58 (46.03) | 12 (9.52) | 22 (17.46) | 5 (3.97) | 3 (2.38) | 12 (9.52) | 12 (9.52) | 2 (1.59) |

As shown in table 4, the most common etiology was IPV, followed by RTA, both mainly related with zygomatico-maxillary complex fractures reporting 31 and 13 patients, respectively. Among patterns of mandibular fractures (51 cases), in 28 patients the etiology was IPV (54.90%). Le Fort I pattern was seen in six cases related with IPV and RTA.

Table 4 Distribution of maxillofacial fractures according to etiology

| Maxillofacial fractures | Patients | Etiology n (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interpersonal violence | Animal attacks | Accidents | Falls | Complicated extraction | |||||

| Road traffic | Sport | Job | Bike | ||||||

| Zygomatico-Maxillary Complex | 71 | 31 (43.66) | 7 (9.86) | 13 (18.31) | 4 (5.63) | 3 (4.23) | 7 (9.86) | 6 (8.45) | - |

| Mandibular | 51 | 28 (54.90) | 3 (5.88) | 8 (15.69) | 1 (1.96) | - | 4 (7.84) | 5 (9.80) | 2 (3.92) |

| Le Fort I | 6 | 2 (33.33) | 1 (16.67) | 2 (33.33) | - | 1 (16.67) | - | - | |

| Pan facial | 3 | - | 1 (33.33) | 2 (66.67) | - | - | - | - | - |

| Orbital floor | 2 | 1 (50.00) | - | 1 (50.00) | - | - | - | - | - |

| Naso-Orbito-Etmoidal | 1 | 1 (100) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Le Fort II | 1 | 1 (100) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Le Fort III | 1 | - | - | 1 (100) | - | - | - | - | - |

The mandibular fracture pattern showed that isolated fractures were most common (n = 49, 96.08%). Three patients had mandibular fractures combined with zygomatico-maxillary complex fractures. Mandibular fractures of the right side were more common (n = 21, 41.18%) than bilateral (n = 16, 31.37%). Left fractures (n = 14, 27.45%) were least common. As shown in figure 1, the anatomical distribution is the following: angle (n = 29), body (n = 17), parasymphysis (n = 16), condyle (n = 4), symphysis (n = 3), and ramus (n = 1).

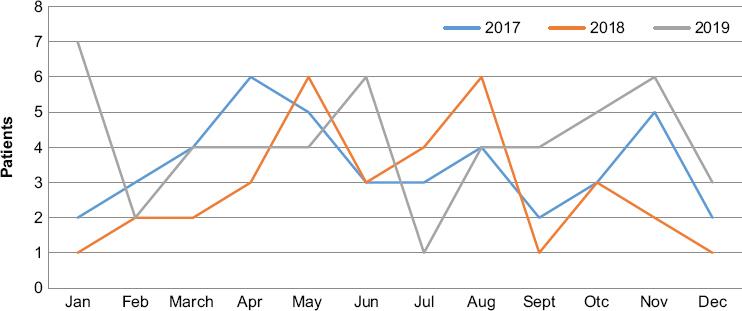

The detail by year and months is presented in figure 2. There were 42 (33.33%) hospital admissions in 2017, 34 (26.98%) in 2018 and 50 (39.68%) in 2019. In this last year, a peak in incidence was noted in January, 2019 (n = 7).

Discussion

Maxillofacial fractures affect the individual not only by limiting the functional aspect, but also hampering the esthetics. MFT needs special attention due to their close proximity to and frequent involvement of vital organs, and for this reason, thorough evaluation of the maxillofacial region is mandatory during the primary stages of trauma care12. In this study, we only included patients treated surgically to obtain an epidemiological profile of the severe MFT in this Cuban hospital.

Trends and characteristics of maxillofacial injuries vary from one population to another depending on certain peculiarities such as socioeconomic, cultural, and environmental factors19. In our study, the sex distribution of maxillofacial fractures incidence is highly frequent in males. The overall male to female ratio was 10.45:1. Our finding was higher than to several previously conducted studies in Brazil (4.63:1)6, Chile (1.7:1)7, Ethiopia (4.02:1)11, India (3.3:1 and 2.9:1)12,15, Iran (4.07:1)16, Nigeria (3.4:1)19, Sudan (2.2:1)21, and Cuba (2.7:1, 2.19:1, and 4.1:1)24-26. These results might be due to that men tend to be more often involved in aggressive and conflict-ridden situations and are mostly involved in outdoor activities than women. Lesser incidence of maxillofacial fractures in females could be because of lesser reporting of injuries - due to either the sex-based neglect still prevalent in many rural areas or domestic abuse14.

With regard to the age, our study showed same number of patients in the 21-40 and 41-60 age groups. We believe this finding maybe associated with the fact that patients of this age represent a group with intense social interaction, participate in dangerous exercises and sports, drive motor vehicles without safety measures, and are more involved in situations of IPV, making them the most susceptible group6.

Esses et al. in Brazil6, Werlinger et al. in Chile7, Teshome et al. in Ethiopia11, Agarwal et al. in India14, Samieirad et al. in Iran16, Shoraourddi et al. in Malaysia18, and Morales et al. in Cuba24-26 reported a high incidence of trauma in young adults in their third decades. Pediatric fractures (≤ 20 years old patients) accounted for 8.73% in our study, which is consistent with literature14,15. In agreement with these previous studies14,15, we did not observe facial fractures before 10 years of age, while their incidence progressively increases with the beginning of school and adolescence. This has been widely reported in the scientific literature that directly associates the lifestyles of the youngest with risk behaviors that increase the probability of suffering intentional or unintentional injuries7.

Trauma has been considered the leading cause of death in individuals aged 1-44 years and the main cause of lost productivity in a specific population6,27. This information highlights the importance of identifying risk factors and use of preventive measures for injuries, as it would reduce the number of deaths, as well as disability or withdrawal from work or student activities, due to trauma28. At present, the association of alcohol, drugs, vehicle management, and urban violence increase is increasingly present in the etiology of facial trauma, even increasing its complexity. Thus, there is a need to know the cause, severity, and time distribution to set priorities for effective treatment and prevention of these injuries, which is related to the identification of possible direct or indirect risk factors for MFT6.

There is a stark difference between the incidence and etiology of trauma in developed and developing countries. In American, African, and Asian countries, RTAs have been shown to be the predominant cause29,30. The present study revealed that IPV (46.03%) was the leading cause of maxillofacial fractures. Our results are similar to experiences reported in Chile6, Ethiopia11, and in France31. In contrast, RTA-related factures were the most common in several studies6,12-16,18,19,21,24-26.

This study revealed a 46.83% of alcoholic ingestion before the trauma. In the multivariate analysis, alcohol consumption was significantly lower as the age increased, as well as in those patients who lived in urban zones. Alcohol involved facial injuries may be more serious than non-alcohol related facial injuries as evident by higher proportion of patients requiring surgery32. Facial injuries from alcohol related trauma places a high burden on hospital resources. As alcohol related MFT can be potentially preventable, educational programs and alcohol intervention strategies should be implemented to reduce such health hazards.

In our study, the zygomatico-maxillary complex bones were the most fractured followed by the mandible. These results can be due to these bones prominence in the viscerocranium, which makes it susceptible to trauma. Furthermore, the zygomatic complex is biomechanically the lateral weight-bearing pillar of the midface, absorbing a large part of the kinetic energy of the wounding agents19,22. Another aspect that should not be neglected is human defense instinct. People are frequently tempted to turn their head at the moment of the trauma, avoiding in this way frontal impact in the middle of the face22,33.

In a study published by Farneze et al.34 in 2016 that described maxillomandibular trauma of Brazilian patients at a reference center in oral and maxillofacial service, this relation was invested. Our results are in accordance with the earlier study from India by Satpathy et al.12 However, they are opposite to previously conducted studies in India13, in Iran16, in Romania22, and in Cuba25,26 where the mandible was the most fractured facial bone.

The majority of the patients in this study had two lines of fractures (39.68%). Contrary to our results, others authors reported a prevalence of patients with a single fracture trajectory22. The mentioned differences can be explained by the fact that the patterns of craniofacial fractures depends on a multitude of factors such as the type, direction, kinetic energy of the injuring agent or the position of the head at the time of the trauma, and especially on the fracture mechanism, leading to many possible variants of association of the fracture foci33.

Our study provide useful knowledge about the current distribution of facial fractures in our hospital, as well as offering a new valuable health-care system database that might improve medical and dental policies to prevent and manage facial trauma. Limitations of the study are that being retrospective; it may be subject to information bias due to inaccurate initial examination and incomplete or incorrect documentation. To minimize this shortcoming, only full medical records were selected.

Conclusions

The majority of the patients in the present study were male, rural, with admission in 2019. IPV remains the major cause of maxillofacial fractures and the young adult males were the main victims in the studied sample. Alcohol involvement is frequent in facial fracture presentations. The most frequent fractures are zygomatic-maxillary complex fractures. The fractures located in mandibular angle were the most frequent in this bone.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)