Introduction

Involvement of dissection flap into the ostium of a coronary artery occurs in 1%-2% of acute Type A aortic dissections. It most commonly involves the right coronary artery, leading to myocardial infarction and, in some instances, atrioventricular (AV) block, probably due to the arterial supply of the AV node, which 90% of the cases originates from the right coronary artery. Herein, we present the case of a complete AV block caused by an aortic dissection flap.

Clinical case

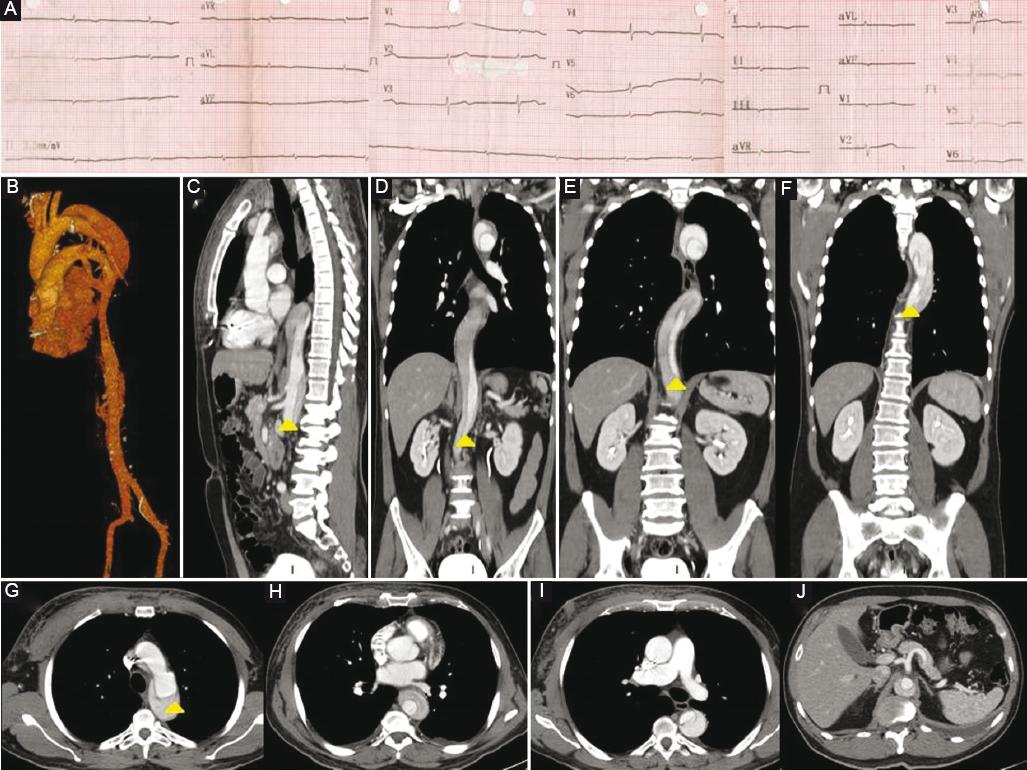

A 59-year-old male with a history of hypertension for 15 years, with inadequate treatment, had chest pain and diaphoresis, for more than 20 min. He went for medical attention at an ambulatory clinic where he was diagnosed with an hypertensive crisis and received an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor. He was referred to a hospital and at his arrival, physical examination was normal, and the electrocardiogram revealed a first-degree AV block so he was discharged home with medical treatment. One day later, the patient had recurrence of symptoms and returned to the emergency room. Vital signs at this arrival were blood pressure 184/79 mmHg, heart rate 58 beats/min, respiratory rate of 19 rpm, temperature 37°C, weight 81 kg, height 1.70 m, and peripheral pulses which were augmented in intensity in all extremities. The electrocardiogram showed a complete AV block (Fig. 1A) and asymmetric T-wave inversion in V4-V6. He underwent measurement of troponin which was positive. The initial medical treatment included aspirin, nitrates, anticoagulation, beta-blocker, calcium channel blocker, and high-intensity statin. Given the difficulty to maintain blood pressure goals, he received nifedipine. Due to his heart rhythm, a definitive pacemaker was placed in DDDR modality. He persisted with blood pressure >160/100 mmHg and chest pain despite medication. Due to this situation, he was taken to coronary angiography through femoral access, but the study was incomplete due to inability to introduce the catheter through the aorta. On aortography, the diagnosis of aortic dissection Stanford A and Debakey I was made and then confirmed through computed tomography (CT) scan (Fig. 1B: three-dimensional reconstruction of aorta. Fig. 1C-J: axial views). Intravenous nitroprusside was initiated and the patient was referred for surgical treatment.

Figure 1 A: Electrocardiogram showing complete atrioventricular block. B: Aortic three-dimensional reconstruction. C: Computed tomography (CT) sagittal view showing aortic dissection. D: CT frontal view showing aortic dissection in the abdominal aorta. E: CT frontal view showing aortic dissection in the thoracic and abdominal aorta. F: CT frontal view showing aortic dissection in the thoracic aorta. G: CT axial view showing aortic dissection and flap in the ascending thoracic aorta. H: CT axial view showing aortic dissection in the descending aorta. I: CT axial view showing aortic dissection in the descending aorta and pacemaker electrode. J: CT axial view showing aortic dissection in the descending aorta without involvement of the mesenteric arteries.

Discussion

Acute aortic dissection is present in about 90% of patients with acute aortic syndromes. Intimal disruption leads to a dissection plane in the aortic wall that may propagate both anterograde and less common retrograde throughout the length of the aorta. According to clinical classifications, Stanford A and DeBakey I represent patients with dissections involving the ascending aorta, aortic arch, and with or without extension into the descending aorta. Involvement of the dissection flap in the ostium of a coronary artery occurs in 1-2% of patients with acute Type A aortic dissection. It most commonly involves the right coronary artery, leading to inferior myocardial infarction1-3.

Aortic dissection is usually not considered an underlying cause in patients with an acute coronary syndrome neither of electric disturbances such as AV block2-4. In this fact lies the importance of a high level of clinical suspicion in the differential diagnosis for patients with chest pain, high blood pressure and AV block. Like in this case, the decision to take the patient to catheterization laboratory was to clarify the diagnosis of inferior myocardial infarction as the cause of the clinical presentation. It is important to consider that the ostium of the right coronary artery flows to the right and anteriorly, passing under through right leaflet toward the AV groove running until the heart’s cross. At this point, it divides in 90% of the cases into two terminal branches: the posterior descendant which goes down throughout the posterior interventricular groove in direction to the apex and the other one through the AV groove. The most important branches of the right coronary artery are the cone artery, in 55% of the cases gives the sinus node artery, 3-4 ventricular branches, and in 90% of the cases, it gives birth to the AV node artery5. This explains why anatomic knowledge is imperative to suspect not only myocardial infarction but also aortic dissection as a cause of AV block. When the diagnostic suspicion is high, accurate confirmation is required with contrast-enhanced computed tomography, magnetic resonance, echocardiography, and aortography6-8. The most common modality is CT scan, showing the presence of two distinct lumina with a visible intimal flap. Stanford A type aortic dissection requires urgent surgical treatment. Medical treatment in the meantime should be goal-directed to achieve systolic blood pressure below 100 mmHg or the lowest level appropriate that permits adequate perfusion with vasodilators and use of beta-blockers to maintain a heart rate below 60 beats per minute. The rationale for this is to reduce the rate of rise in the ventricular force (dP/dT) and stress on the aorta1-3,9.

Conclusions

Aortic syndromes should be considered as differential diagnosis in hypertensive patients who develop chest pain and AV block. Medical treatment has to be directed to maintain systolic blood pressure below 100 mmHg and heartbeat below 60 mmHg with vasodilators and beta-blockers. Surgical approach is the treatment of choice for Stanford A type aortic dissection.

nova página do texto(beta)

nova página do texto(beta)