Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Textual: análisis del medio rural latinoamericano

versão On-line ISSN 2395-9177versão impressa ISSN 0185-9439

Textual anál. medio rural latinoam. no.72 Chapingo Jul./Dez. 2018

https://doi.org/10.5154/r.textual.2018.72.004

Social movements and rural culture

Rural harmonic development. A theoretical proposal from the subjects

1Colegio de Postgraduados, Posgrado en Ciencias: Estrategias para el Desarrollo Agrícola Regional (PROEDAR), Campus Puebla, km 125.5 carretera federal México-Puebla (actualmente Boulevard Forjadores de Puebla), C. P. 72760, Puebla, Puebla, México. disalvar1@yahoo.com.mx (*corresponding author).

2Colegio de Postgraduados, Campus Puebla, km 125.5 carretera federal México-Puebla (actualmente Boulevard Forjadores de Puebla), C. P. 72760, Puebla, Puebla, México.

3Universidad Autónoma Chapingo, Centro Regional Universitario Oriente (UACh-CRUO). km 6 carretea Huatusco-Xalapa, Huatusco, Veracruz, México. C.P. 94100.

Economic globalization and neoliberalism, imposed for more than three decades, have generated situations in the limit: i) widespread poverty and social polarization and, ii) environmental deterioration and increased climate change. As a theoretical part of a broader study, in the search for alternatives to the current sustainable development model, characterized by generating conditions of "non-development" for the majority of the population; the category of harmonic development is proposed. The guiding axis of this work emerges from a position critical to sustainable development, proposing an alternative that incorporates as a main element the human being, as a subject of its own development. The harmonic development is postulated from the dynamic articulation of three axes: social and economic transformations centered on the human being, the preservation of nature and the organizations and instances of mediation; in the search for regulation and the joint balance of these three axes, in social, economic, cultural and political activities, in a participatory and equitable approach. It is an initial proposal, as a conceptual notion to walk, in the perspective of living harmoniously. A way to "weave in chaos and build alternatives".

Keywords: alternative development; development subjects; harmonious living

La globalización económica y el neoliberalismo, impuestos por más de tres décadas, han generado situaciones en el límite: i) pobreza generalizada y polarización social y, ii) deterioro ambiental y aumento del cambio climático. Como parte teórica de un estudio más amplio, en la búsqueda de alternativas al modelo de desarrollo sustentable actual, caracterizado por generar condiciones de “no desarrollo” para la mayoría de la población; se propone la categoría de desarrollo armónico. El eje conductor de este trabajo se desprende de una posición crítica al desarrollo sustentable, proponiendo una alternativa que incorpora como elemento principal al ser humano, como sujeto de su propio desarrollo. El desarrollo armónico, se postula desde la articulación dinámica de tres ejes: transformaciones sociales y económicas centradas en el ser humano, la preservación de la naturaleza y las organizaciones e instancias de mediación; en la búsqueda de la regulación y el equilibrio conjunto de estos tres ejes, en las actividades sociales, económicas, culturales y políticas, en un enfoque de participación y equidad. Es una propuesta inicial, a manera de una noción conceptual para caminar, en la perspectiva del vivir armónico. Una forma para “tejer en el caos y construir alternativas”.

Palabras clave: desarrollo alternativo; sujetos desarrollo; vivir armónico

Introduction

The proposal is elaborated in the articulation of two complex concepts: that of development; and that of the subject. The concept of subject and his impulse, as a conscious being, with free will, independent, autonomous and responsible for his actions is considered indispensable to construct alternatives for the common good. In this dissertation only the concept of development is referred to, of which an excessive number of papers have been written and used to support an ideology with different meanings for more than sixty years; the notion of harmonic development or living in harmony, is proposed as an alternative, which includes as a central axis, the human being as a subject that generates his own strategies. Besides a review and critique of the postulates of development, an emphasis is placed on the theoretical construction of harmonic development, or a living in harmony approach, having as a basis the elements of preparation of the current actors towards becoming subjects. In fact, a form of promotion is conceived from the agent (things or people, which cause processes to happen), the actor (individuals or collectivity, who carry out the processes, without questioning their role) and subjects (individual or collective per sons, performing the processes in a network, with decision and responsibility for their acts). It should be noted that the agency is present transversally in this trajectory from the agent, the actor and the subject.

The proposal of harmonic development is made in the perspective of constructing local and regional development strategies, taking into consideration the countryside and urban areas. The central premise is that those who initiate and promote devel opment processes are the agents, actors, and individuals that survive and act in local areas with the population that is involved and included in the analytical processes, of reflection and their own decision making from these spheres.

Context of the multidimensional crisis

Globalization as a process and neoliberalism as a policy have been imposed on a global scale since the decade of the 70s, supported by the IMF, WB, WTO and OECD1 The defenders of this global phenomenon outline as advantages very limited advances: expansion of freedoms, generation of employment, better health, economic growth, advances in women’s rights, and the reduction of child labor, among others (Giddens, 2000).

Input and analysis from different authors allow the affirmation that, after three decades of applying neoliberalism and economic globalization, governments and public policies, formal and real carried out have caused two central problems: i) general poverty and social polarization, and ii) environmental deterioration and loss of natural resources in many countries of the world, such as in Latin America and Mexico. The rate of climate change, resulting from industrialization and pollution generated by activities that overuse natural resources, especially in the last two centuries, is intensifying these problems (Chomsky, 1997; Boff, 2009; Boltvinik, 2012; Delgado & Márquez, 2012; Bartra, 2013; Ortiz, 2014; Piketty, 2014). In view of this situation, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) were adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations to face the complex world situation as a response by this international organization and other actors.

However, the civilization crisis of a multidimensional and inhuman nature (Bartra, 2013), generated by the current stage of development of capitalism with strong income inequality (Piketty, 2014), should help to alert and support the implications of the increasing social polarization in which there is the certainty of two real risks for humanity in its dynamics: climate change and a third world war (Wallerstein, Collins, Mann, Derluguian, & Calhoun, 2015).

The global crisis is not only financial, nor solely affecting the biosphere and human relations, it is a credibility crisis for the new generations in their prospects for the future (Morin, 2010). It is evident that the promise of sustainable development, including economic, social, environmental, and cultural development is more and more an empty offer, a lie in countries with less economic development, be it promot ed by national governments or by international organizations.

The Mexican government and the policies applied for more than three decades have aggravated the impact on the country, states and regions. In its historical development and even more, at the end of the first decade of the 21st century, Mexico is conspicuous for its contrasts. The majority of the population is located in the cities and almost a quarter of the population is in localities of less than 2,500 inhabitants. The number of Mexican migrants residing in the United States is 11.4 million, of which seven million are illegal migrants and remittances have become a pillar of the national economy. In the international context, the Mexican economy ranks twelfth and eleventh among the exporting nations. This wealth is distributed very unequally and 46.2% of the population lives in impoverished conditions, with 11.7 million people unable to acquire the basic food basket (Márquez, 2014. p.11). Although, at the beginning of 2018, a total population was estimated of 124.7 million inhabitants (CONAPO, 2017) and the emigration rate has stabilized, in Mexico there is an important demographic bonus which represents in the current situation a relevant factor for proposing alternatives for development in cities and rural areas.

One of the indicators that best synthesizes the development situation at different levels is the Human Development Index (HDI), which, adjusted according to the existing inequality, places the world average at 0.548. The five countries with the highest development (Norway, Australia, Switzerland, Denmark and the Netherlands) have an index of 0.866. Mexico has one of 0.587 and ranked 86 out of a total of 189 countries in 2014 (PNUD, 2015, pp. 28-31).

The Mexican economy has been in a slow growth trap for three decades (Ros, 2015) and a significant number of programs implemented through public policy have not generated any improvement in the population, nor in their productive activities (Herrera, 2012). Stagnation that, interacting with the concentration of income and wealth, limits the expansion of the internal market, increases informal commerce, reduces productivity, and the income of workers, and fosters inequality being the latter one of the causes of national insecurity, crime, and violence.

Problem and general hypothesis

In the context of international crisis and national stagnation, a set of critical points of the problematic question was identified which was called scarce development or “non-development” (Toledo & Barrera, 2008, Aziz, 2012, Calva, 2012, Delgado & Márquez, 2012; Rubio, 2014). Viewed in the complete study, the problem related to the reduced participation of actors and local/ regional subjects in the generation of proposals and alternatives to the current development. In an environment of globalization and hegemonic neoliberal politics, the general question that is established at this theoretical level is the following:

Is it possible to advance in the construction of a harmonic development proposal from the actors and their constitution as subjects of their own development?

In this articulation of elements for the construction of alternatives to the existing scarce development and the formation of their own development by subjects, we propose as a hypothesis of general study that for the projection of actors towards subjects the following principle elements should be considered: i) obtaining philosophical grounds about being an individual and organized, ii) the multilevel location of local and regional processes, iii) the application of the notion of the harmonic development of human beings among themselves, the human being with nature, and the generation of mediation organizations and institutions, a topic that motivates this essay, and iv) the generation of alternatives specific to the current scarce development or “non-development”.

Study method

The applied method lies in the field of qualitative research for the understanding and motivation of actors and subjects (Corbetta, 2007; Bonilla, Hurtado, & Jaramillo, 2009; Denzin & Lincoln, 2011; Hernández-Samperi, Fernández-Collado, & Baptista-Lucio, 2014; Morales-Vazquez, Benavides-Ilizaliturri, Reséndiz-Ortega, Haro-Zea, Franco-Hernández, & Al Dixan-Acosta, 2015), and in the construction of the proposal for harmonic development or living in harmony.

At this stage of the research, the systematic search for theoretical information and experiences was carried out regarding development and issues, classifying documents by topic, applying comprehensive, reflexive, and critical reading, collecting directly from libraries and bookstores, using tools such as search engines in electronic information banks (redalyc, scielo, annual reviews, dialnet, sidalc, remba, resdicyt-colpos, scie and ssci indexes, among others), making conceptual maps and schemes, preparing referential synthesis and trying to build the metatheory and conceptual proposals, like that of harmonic development or living in harmony that is posed far and beyond sustainable development and as a projection of good living.

The concept of harmonic development was designed in the dynamic articulation of three axes or components, namely: those that concern the human being, the preservation of nature, and mediation organizations and institutions in the search for regulation and balance within the entire joint process. As a starting point, to construct this theory and through its application in specific regions, to gather experiences, applying the six indicated principles and others that are included which will be considered as appropriate, in the three components or axes of harmonic development.

The proposal of harmonic development or living in harmony is discussed below, and some concluding reflections are made at the end.

1. The proposal of harmonic development

Since the 90s in the twentieth century, the concepts of progress as an idea that history advances continually ascending, and development as a process of change towards higher levels of life have been questioned by society at risk and the current civilization crisis where the global and neoliberal economic radicalization are leading to a world without a future utopia, nor human sense. Under these conditions, the most viable option is the construction of new paradigms, of theory and alternative practices, associated with universal morality and the search for greater justice in humanity (Ávila, 2007, Ortíz, 2014). It is necessary to move away from the pessimistic extremes of catastrophic civilization, or blind optimism proclaiming that market, science and technology will solve the prevailing multifactor crisis.

First of all, in the face of this issue of social polarization and environmental deterioration, it is important to consider the territorial approach to development, which as a social construct includes rural and urban areas, in a process of structural change and different scales. It emphasizes territorial and social cohesion, endoge nous and regional development (Echeverri & Moscardi, 2005, Riffo, 2013, Berdegué, et al., 2015) in a larger vision of both spaces of the territory.

Relevant antecedents come from the first report of the Club of Rome in 1972 and the Brundtland report in 1987 from which proposals for development were proposed under the “eco-development” approach (Leff, 2007), ecology, and food self-sufficiency, and the proposal of normative and control instances from the local levels (Blauert & Zadet, 1999) and its counterpart, international government authorities. These theories of development, including the multi-cited version of “sustainable”, understood as the development oriented to satisfy the present needs, without undermining the capacity of future generations to satisfy their own needs (Monfort & Guillaumín, 1992), involve a rethinking of the ecological, economic, social, political, and cultural aspects because they mention a human world, which seeks to respect nature’s resources.

In effect, the invention of “development” has been one of the strategies of cultural and social domination (Escobar, 2012), creating a conceptual effervescence and social practice, starting with critical thinking and knowledge sociology being one of five new areas for the generation of alternatives to development (Escobar, 2014). Sustainable development, as the most recent version of the notion of “development” (Ávila, 2007), is a representation and legitimization of the history, culture, and myths of the West which is why it is not applicable globally. This idea of development is not viable as an inexhaustible source of resources and wealth, with the continuous growth of goods and services of the entire economy. Sustainable development conjuring an agreement of opposites (an oxymoron), is a form of legitimating camouflage, in such a way that the levels of consumption and comfort are not drastically reduced, that the environment does not deteriorate and can continue reproducing, and that there are enough natural resources for future generations, which is today the paradigm of the sustainable development model.

An assessment of the world situation at the beginning of the 21st century reveals that neither “development” nor “sustainability” correspond to the processes harming the world (Moreno, 2013). One lives peacefully in the oxymoron, something like “reasonable madness”; but the elites are concerned because the basic needs of most of the population are not being met and the development of the rich countries increases the gap with the poorest nations.

Facing the voiding of sustainable development, the concept of good living, based on the harmony of the human being with himself and with his fellow neighbor has been building for two decades in South America (Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia and Colombia), reversing the deterioration, recovering what is possible and contributing to the regeneration of nature. A utopia for walking2, where harmonic relations between the countryside and the city and the man-nature relationship are sought. The good life, sumak kawsay, means in a broad sense “life to the fullest”, feeling good about yourself, living in harmony, with respect and balance with what exists through the understanding that everything is interconnected. The concept and perspective of good living is one of the contributions of the original peoples of America towards the development and fullness of human beings. It is an alternative conception to the development models of Western civilization which goes beyond sustainable development and that coincides with other approaches of indigenous peoples from other regions of the world: Asia, Oceania and Africa (Giraldo, 2014). The concept of good living appears in several expressions of native languages and it is about leading a simple life, reducing consumerism, keeping production balanced, without damaging the environment, living in harmony with people and nature where there is no room for inequality or poverty of many people so a few can live very well. It is sharing and complementing each other, defending life and humanity itself in this era of survival.

In line with the processes of criticism of neoliberal hegemonic modernity, contributions have been made to the debate about the horizons of change in Latin America, with two important challenges: i) broadening the analysis regarding the scope of good living, and ii) evaluating the relations of power, contributions and limits of the so-called progressive regimes, particularly in the Andean region. In the current political moment of reflections on hegemony and counter hegemony recovering the Gramscian perspective one of the issues to be included on the agenda is, to what extent do the protagonist social subjects of change, affirm or not, in the constructs of a democratic nature? (Hidalgo & Márquez, 2015).

As a means of projecting good living (sumak kawsay), aimed at essentially mestizo communities and populations, we propose in this research the notion of harmonic development or living in harmony. A brief background reference indicates that the category of harmonic development has been used in a number of different situa tions. From family and child development, through education and pedagogy, and in architecture it is a reference of balance. It has been considered a challenge for a healthy life, and even in disarmament negotiations between countries, it refers to peaceful coexistence and harmonic development (Hernández, 2002). Related to scientific development, (Villaveces, 2005) uniting technology and society in a harmonic counterpoint is proposed because, the separation of the culture of social sciences and the culture of natural sciences has completely deteriorated understanding.

Adorno’s text (2015) , “An introduction to the Harmony of the Universe”, published in English, in 1851 and recently translated into Spanish, is a close reference to the idea of harmonic development, broadened to the cosmos and situated in the scientific, cultural and technological development of that time. The harmonic development that we propose is a notion that allows us to take advantage of the theory and practice of “good living” as a fundamental axiological3 contribution of the cultural tradition of the original communities, not only in the colonized countries, presently with less economic development generally, but also in the countries of greater economic development because the process of industrialization, urbanization, and outsourcing of the economies has included the imposition of the urban-industrial circle and the abandonment of the rural environment, especially the areas of peasant and indigenous agriculture and their logic of production-conservation, which indicates the trajectory towards a post-industrial society (Izquierdo, 2013), taking up the role of the great historical cities (Echeverría, 2013) where urban and rural development are linked. Based on the approaches of good living and the evidence of scarce or “non-development”, the notion of harmonic development or living in harmony that we propose incorporates the following initial principles and their implementation perspective:

The individual and his alterity.4 As a basis for improving human relationships, be- tween individuals and in groups or net- works of actors and individuals.

Reduction of social inequality. In the face of poverty and polarization, it is an un- avoidable aspect in any proposal of alternatives to development.

Respect and preservation of nature. It is essential to improve man-nature and country-city relationships.

Cultural and political multi-diversity. Respect for cultural diversity and political plurality is fundamental, with awareness, ethics, and participatory democracy.

Social inclusion and non-discrimination. They are a measure of the search for the common good and the construction of collective alternatives.

Education and self-awareness. In the training of actors and individuals, it is very important for there to be progress in autonomy and independence of thought and action.

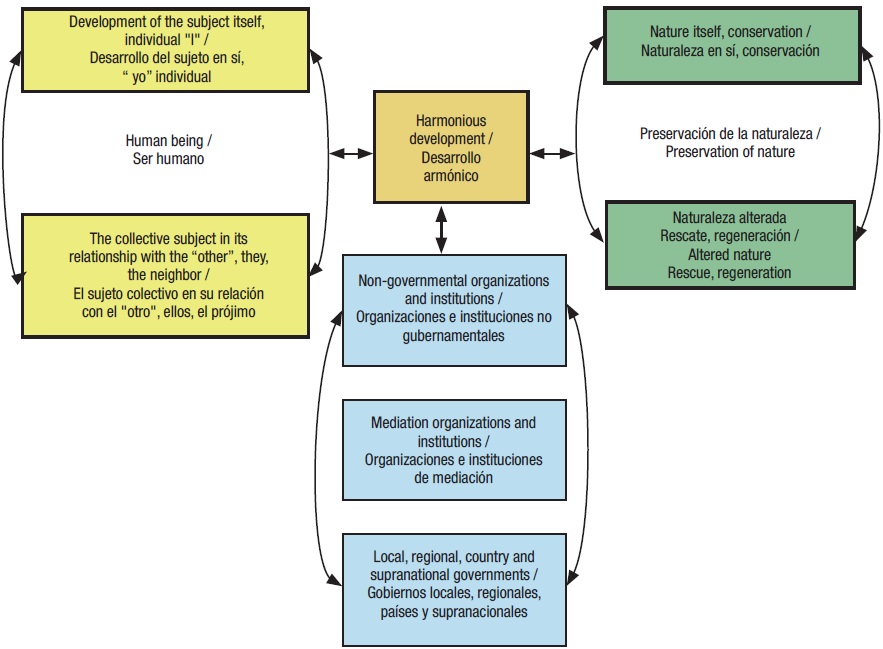

As a process in construction, the term “development” seems to be the closest term to good living, beyond “sustain able development” and other operative schemes (Gudynas & Acosta, 2011) where human dignity is the supreme value of development (Castells & Himanen, 2016). A simplified scheme of this proposal of harmonic development entails the articulation and dynamic interdependence of three axes or components: that of the individual and collective human being, the preservation of nature, and the organizations and institutions of mediation in the pursuit of regulation and balance in the set of processes. It is evident that the human being is present in the other two components and hence the insistence on the indispensable consideration of agents, actors and subjects, in the construction of alternative proposals to development (Figure 1).

Source. Compiledby authors. April, 2016.

Figure 1. Proposal for harmonic development, as a useful concept in the face of the civilizational crisis of the 21st century.

In the case of human beings and the relationships with their peers, harmony (Gr. harmonia) has to do with the proportion and proper relationship between the elements of a whole, friendly relationships without tension, and conviviality between two or more people, and in the case of music, it is the art of training and linking chords. In the evolution of Greek thought, Pythagoras discovers the musical octave as a mathematical ratio and proportion of harmony in music that permeated all the sense creations of the Hellenic spirit (Nicol, 2004). In a simile to a musical instrument, the harmony of the body and soul (Geymonat, 2009) is considered very important in humans. It is the integration of the development of the human individual and his relationship with others, the preservation of nature, and the creation of associations, organizations, groups and entities of mediation which contribute to these purposes.

1.1. The human being in the harmonic development

From the human component, which includes the actors and subjects of development, its identification and constitution must be carried out from the local (rural communities and neighborhoods in the cities), as a premise to generate alternatives to development, ‘down up’ as proposed by Bardach (1998), in its eight steps for the analysis of public policies, contrary to the logic of up down, which predominates in the planned intervention proposals (Long, 2007), even in those that achieve acceptable levels of the actors’ participation. It is a fact that, in the development processes, both logics must be combined and complemented in the long term as a complex system or as a pincer of development.

For the design of the conceptual map of the analysis human beings, from the perspective of the construction of the subjects for Harmonic Development, the subjects’ theoretical and methodological approaches were considered. Among the theoretical elements are the allusion to the Cartesian subject, as the “thorny subject” (Žižek, 2011), the actor-network in its proposal to reassemble the social (Latour, 2008), the subject in his double role, object of study (objectified), while being the subject (subject) of Foucault (1999) , the construct as a conscious subject in search of new horizons that make history with awareness (Zemelman, 1998; 2012), and the controversial notion of the subject and his dissolution by prioritizing objectivity (Morin, 1994).

Regarding the methodologies, those related to the Human Development Index (HDI), including the recent adjustments made, were considered in the estimation of the index based on the economic and gender inequality existing in the nations (UNDP, 2016): human development as freedom and capacity building, in particular: i) what are people really capable of doing and being?, and what real opportunities are available for you to do or be which can be? (Nussbaum, 2015), the situations of inequality that limit this development of the human being, in many regions and countries of the world (Sen, 2010), and the proposal of good living as an alternative to current capitalist development, and on the contrary, to seek harmony in the relationship between men and of men with nature (Acosta, 2014), and the situation of multifaceted poverty (Boltvinik, 2012).

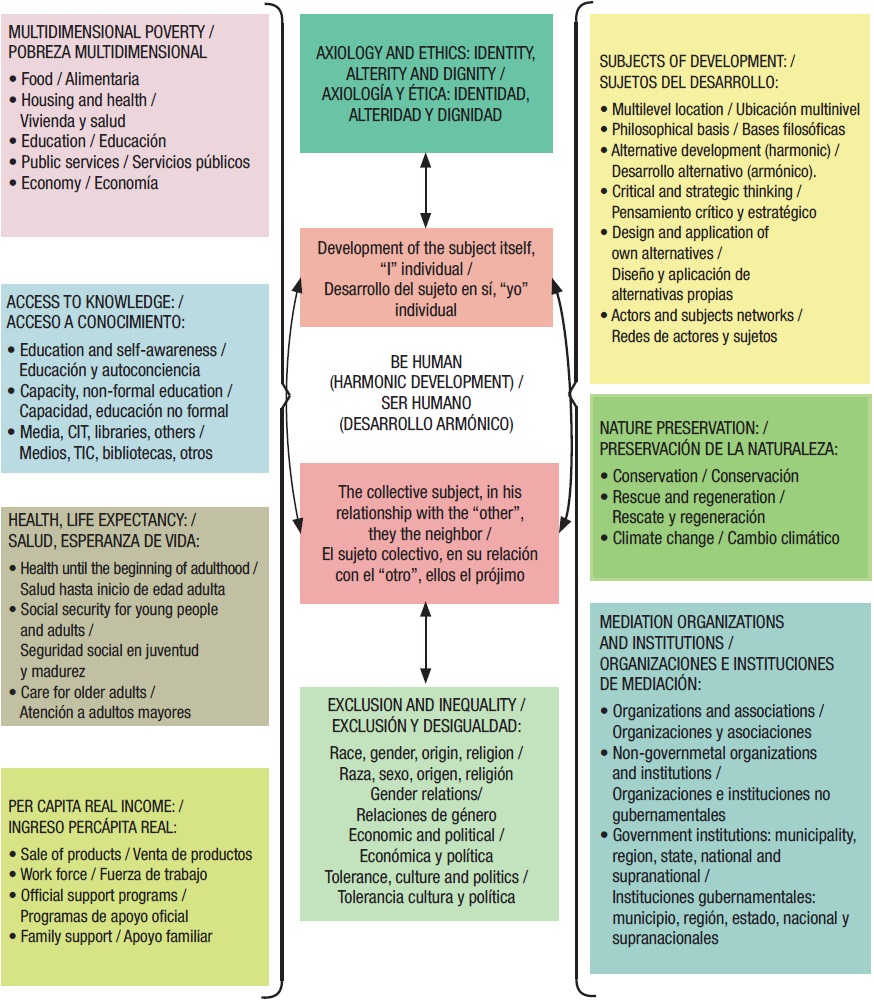

With the human being as the first axis or component of Harmonic Development, situations of exclusion and inequality, which can limit the drive of the subjects, must first be dealt with (Fowler & Kay, 2003; Díaz, 2014), until ascending to the last concepts that will indicate a greater advance in drive, participation, and actions. These are, by way of example, axiology, ethics, identity, alterity and, above all, dignity with which subjects must be led (Figure 2).

Source: Compiledby the authors, April, 2017. Based on UNDP, 2016; Nussbaum, 2015; Acosta, 2014; Žižek, 2011; Sen, 2010; Latour, 2008; Foucault, 1999; Zemelman, 1998 and 2012; Morin, 1994.

Figure 2. The human being as a component of the Harmonic Development: construction of subjects.

In the impulse and construction of subjects of Harmonic Development, as a search for alternatives to current inhuman capitalist development, a basic consideration lies in the sense that “in the production process not only a relationship between man and nature is established, but also a relationship of men among themselves” (Marx, 2000, p.9). Thus, the seven groups of elements that are considered for the development of the human being are: multidimensional poverty, access to knowledge, health and life expectancy, real per-capita income, the subjects of development and the other two components of harmonic development from the perspective of the human being.

1.2. The preservation of nature

The risk to civilization posed by climate change as a result of the environmental deterioration caused by human activities, especially in the last two hundred years, as evidenced by the reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2014) sponsored by UNEP-UN and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) has been pointed out. In view of this, the preservation of nature as an indispensable necessity is proposed as one of the three axes. Certainly, seven billion human beings already cause an environmental impact, but the challenge of this conglomerate in constant increase is how to diminish the increasing negative effects of this presence and human activities in nature, towards a harmonic life in time.

The multiple events and cases of pollution, global warming, the melting of the polar caps, the loss of soils, vegetation cover, and biodiversity are clear evidence that industrialism has involved the increasing destruction of the “natural means of subsistence of society” in two versions of contrasting social systems: state socialism or market economy (Schmidt, 2014), under the common inclinations of the domination of nature and society, in the perspectives of unlimited technical progress and growth.

A recent reference dealing with the preservation of nature is that of Ecuador where the meaning of natural heritage with its own right was established in the Political Constitution (2010) at the same level that health and education are taken care of (Gudynas, 2011). In Mexico, the notion of socio-environmental risks is used (Sánchez-Alvarez, Lazos-Chavero, & Melville, 2012) to refer to the destruction of wild areas, water polluted by industries and urbanization, the deterioration of rural environments due to the impact of mining, soil erosion, excessive use of agrochemicals, even the risk of using transgenic seeds, while at the same time, the opposition countryside-city, as referred to by Echeverría (2013) , and that concerns the human civilization process remains unresolved. In local and regional conditions of Mexico, the preservation of nature, as protection and anticipatory protection, of some current or future damage, essential for living in harmony is proposed (Figure 3).

1.3. Mediation institutions and organizations

The State as a historical social formation includes the government and institutions created to regulate individual and collective relationships among citizens, as well as between States. Personal freedom is the key political legitimizing element and it is essentially about power or cooperative relationships established between citizens and collectivities.

On the side of society, a diverse set of organizations with different objectives and interests are generated, but all framed in ways of coexistence between human beings and of these with the institutions. The areas in which these organizational functions are carried out are extensive and diverse accordance with the groups and social classes involved for development and social coexistence with diverse objectives such as: educational, health, cultural, political, resistance, economic, environmental, gender, spiritual, religious, infrastructure management and public services, among others. In a capitalist society with high degree of social polarization as in Mexico and other countries, power and conflict relations predominate over cooperative actions and activities.

It is relevant to resort to the notion of panopticism5, as one of the characteristic features of power relations in our society where power is exercised over individuals, in three fundamental forms: surveillance, control, and correction for the “transformation of individuals according to certain norms” (Foucault, 1999, p. 547). This strategic and rational action must take into consideration that power is a socially mediated construct where individuals and collectivities move in networks with codes of meaning applying their creative capacity (Arteaga, 2012) many times in processes of circumvention, resistance, survival, and even of confrontation. One objective is to generate certain conditions of governability, imposing the hegemony of the dominant social structures and forces to obtain results in favor, applying their economic, political, and military strength (Oliver, 2013). The crisis of legitimacy of politics, parties, and politicians are factors that justify by themselves the search for alternatives to institutional action in the State as a whole, in our case, in the perspective of harmonic development.

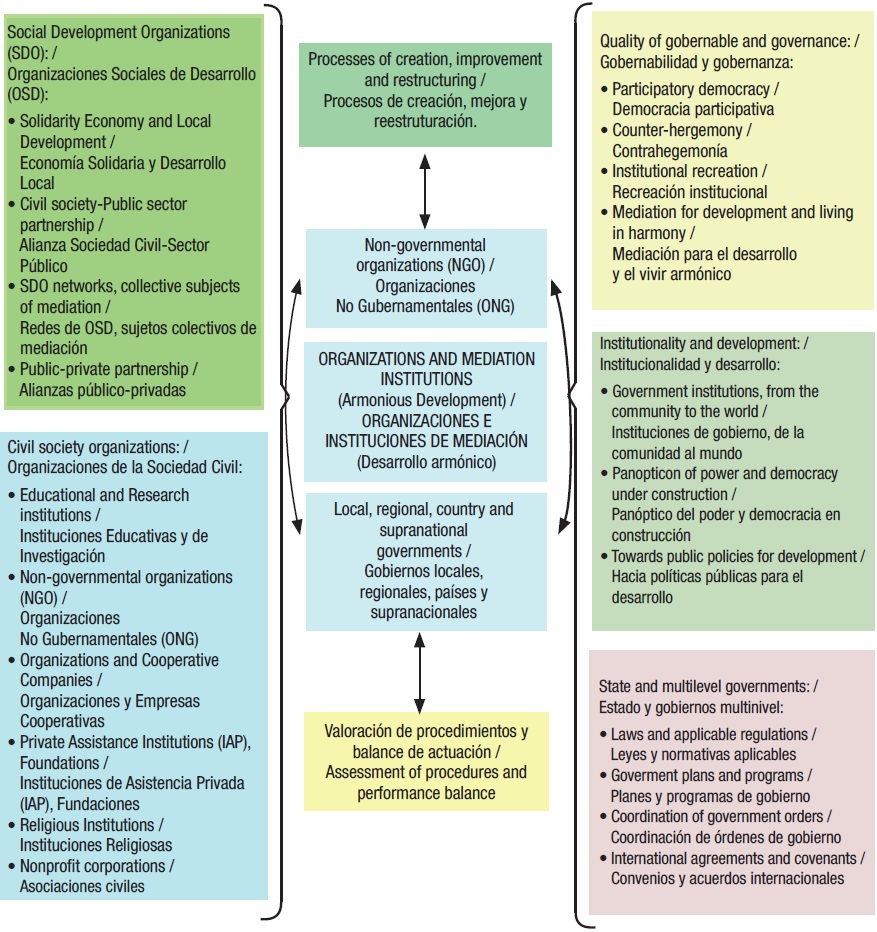

Civil society organizations (CSO) and social development organizations (SDO) include academic institutions, research centers, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), civil associations, religious institutions, cooperative enterprises, and private initiative engaged in (TN resolving) social and environmental problems. In the framework of current sustainable development problems, they seek to design and apply common strategies to reduce environmental impact, among others, to reduce the ecological footprint and promote the acquisition of knowledge and new values about the environment. From this perspective, the transformation of organizations from being actors to subjects of their own development is proposed which implies changing the predominant power relationships (Figure 4).

Source: Compiledby authors, July, 2017.

Figure 4. Organizations and mediation institutions for Harmonic Development.

One of the most cited documents on the topic of the new institutionalism is that of Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance (North, 1993), which proposes a long-term analysis and a theory focused on the sociological study and the economic effect of the institutions which impose formal and informal constraints on the choices available to individuals, generate social stability, and cause certain transaction costs. Articulating the analysis of institutions and organizations, the concept of mediation is generated as a means of looking at and interpreting human relationships. This form of mediation has reached rapid expansion in different areas by being considered as the first option in the resolution of a range of problems: family, school, commercial, international, neighborhood or community-social, and organizational, labor conflicts, environmental, health, or among citizens in general (Gómez-Funes, 2013). Mediation is of interest for the solution of conflicts in different areas, but in this case, it will be used as part of harmonic development in processes of evaluation of procedures and a balance of actions of organizations and institutions to find alternatives for improvement, restructuring, and proposing the creation of new agencies.

Conclusions

In the current “development” model, under the postulates of neoliberalism and globalization, it seems that people and life are disposable, fostering an obsession with economic growth which has eclipsed the concern for sustainability, justice and human dignity. As a dream of economists, businessmen and politicians and seen as a measure of progress, this type of economic growth without limits hides the poverty generated through the destruction of nature, transforming the notion of sustainable development into an empty proposal, without real content, that is leading to a world without a future utopia and without human sense. This sustainable “development” implies the unlimited availability of wealth and resources, alongside of the unlimited availability of resources and riches, with the continuing growth of goods and services, of all the economy; it evokes the agreement of opposites (an oxymoron) and is not viable, unless the levels of consumption and comfort are significantly reduced, mainly in the countries with greater economic development.

We have been moving in the last three decades towards a multidimensional cri sis, which without exaggeration is also a civilization crisis whose impacts demand a change of paradigm and the search for alternatives from countries, regions and localities with actors and subjects responsible for their own development. In the face of sustainable development as an empty concept, the notion of good living is being built in South American countries, based on the harmony of the human being with himself and with his fellow neighbor, reversing the deterioration, recovering the possible and contributing to the regeneration of nature. Based on good living and before the evidence of the scarce or “non-development”, we propose the notion of Harmonic Development or Living in Harmony in the dynamic articulation of three axes or components, namely: those that concern the human being, the preservation of nature, and the organizations and instances of mediation, with regulation and balance in the set of processes. The following six initial principles are considered, which will be applied transversely, as appropriate, in the three axes indicated: i) The subject and his alterity, ii) a reduction in social inequality, iii) the respect and preservation of nature, iv) cultural and political multi-diversity, v) social inclusion and non-discrimination, vi) education and self-awareness. These principles, and others that are relevant, are aimed at contributing to the viability of Harmonic Development through actors and subjects of their own development, attending to three types of ontological relationships inherent in the development of civilizations: the man-nature relationship, coexistence between human beings (the individual and the collective being), and the countryside-city relationship.

Given the civilizing risk that climate change represents, as a result of the environmental deterioration caused by irresponsible human activities, the preservation of nature becomes essential, for protection and as an anticipatory safeguard against some current or future damage that may affect the perspective of Living in Harmony. Regarding institutions and organizations in a capitalist society, with high social polarization, as in Mexico and other countries where the relations of power and conflict are predominant on the actions and activities of cooperation, the concept of mediation is generated as a means of looking at and interpreting human relationships. Although mediation is aimed at resolving conflicts in different areas, in our case it will be used as part of Harmonic Development, in the evaluation of processes and performance balances of organizations and institutions to find alternatives for improvement, restructuring, and to propose the creation of new agencies as a way to “manage chaos and build alternatives”.

REFERENCES

Acosta, Alberto. 2014. El buen vivir más allá del desarrollo. Págs. 21-60. EN: Buena vida, buen vivir: imaginarios alternativos para el bien común de la humanidad/Gian Carlo Delgado Ramos (coordinador). México: UNAM, Centro de Investigaciones Interdisciplinarias en Ciencias y Humanidades, 2014. 443p. [ Links ]

Adorno, Juan Nepomuceno. 2015. Primeros escritos. Introducción a la armonía del universo. Melografía o nueva notación musical. Análisis de los males de México y sus remedios practicables. Editores: Illades, Carlos y Sandoval, Adriana. Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana. México, D.F. 548 p. [ Links ]

Arteaga Botello, Nelson. 2012. Vigilancia, poder y sujeto. Caminos y rutas después de Foucault. Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México- Ed. ITACA. Toluca, México. 138p. [ Links ]

Ávila, Ricardo. 2007. Progreso y desarrollo. A modo de extroducción. Estudios del Hombre, 22. Serie Ensayos. CUCSH-UdeG. Guadalajara, México. Pp. 173-213. [ Links ]

http://www.publicaciones.cucsh.udg.mx/coleccio/esthom/coleh22.htm [ Links ]

Aziz Nassif, Alberto. 2012. Desarrollo en América Latina: tres casos contrastantes, México, Brasil y Argentina. Págs. 21-37. EN: Si se puede. Caminos al desarrollo con equidad. Vol. 16, 342p. Colección Análisis Estratégico para el Desarrollo. Juan Pablos Editor. México, D.F. [ Links ]

Bardach, Eugene. 1998. Los ocho pasos para el análisis de políticas públicas. Un manual para la práctica. Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económica y Miguel Ángel Porrúa. México. 149p. [ Links ]

Bartra, Armando. 2013. Crisis civilizatoria. EN: Crisis civilizatoria y superación del capitalismo. Raúl Ornelas, Coord. UNAM-Instituto de Investigaciones Económicas. Pp. 25-71. [ Links ]

Berdegué, J.A. et al. 2015. Territorios productivos para reducir la pobreza rural a través del incremento de la productividad, la producción y los ingresos. RIMISP. Documento de trabajo. Santiago de Chile. Febrero, 2015. 45p. [ Links ]

Blauert, J. y Zadet, S. Coord. 1999. Mediación para la sustentabilidad. Construyendo políticas desde las bases. Plaza y Valdés-CIESAS-IDS. México, D.F. 415 p. [ Links ]

Boff, Leonardo. 2009. ¿Ángel o demonio? El hombre y la explotación ilimitada de la tierra. Ed. Dabar. México, D.F. 200 p. [ Links ]

Boltvinik, J. 2012. Pobreza y persistencia del campesinado. Teoría, revisión bibliográfica y debate internacional. Mundo Siglo XXI, revista del CIECAS-IPN. Núm. 28, Vol. VIII, 2012, pp. 19-39. [ Links ]

Bonilla Castro, E., Hurtado Prieto, J. y Jaramillo Herrera, J. 2009. La investigación. Aproximaciones a la construcción del conocimiento científico. Ed. Alfaomega. México, D.F. 439 p. [ Links ]

CONAPO, 2017. Proyecciones de la población por entidad federativa, 2010-2050. Consulta: 13 de marzo, 2018. http://www.conapo.gob.mx/es/CONAPO/Proyecciones_Datos [ Links ]

Calva Téllez, José Luis. 2012. Políticas agropecuarias para la soberanía alimentaria y el desarrollo sostenido con equidad. (págs. 67-92). EN: Calva Téllez, José Luis (Coord.) 2012. Políticas agropecuarias, forestales y pesqueras. Vol. 9, 508 p. Colección Análisis Estratégico para el Desarrollo. Juan Pablos Editor. México, D.F. [ Links ]

Castells, Manuel e Himanen, Pekka (Eds.) 2016. Reconceptualización del desarrollo en la era global de la información. Fondo de Cultura Económica. Santiago de Chile. 378 p. [ Links ]

Chomsky, Noam. 1997. Pocos prósperos, muchos descontentos. Ed. Gandhi. México, D.F. 122 p. [ Links ]

Corbetta, Piergiorgio. 2007. Metodología y técnicas de investigación social. Ed. McGraw Hill. Madrid, España.422 p. [ Links ]

Delgado Wise, Raúl y Márquez Covarrubias, Humberto. 2012. Reestructuración capitalista, exportación de fuerza de trabajo e intercambio desigual Págs. 159-180. EN: Calva Téllez, José Luis (Coord.) 2012. Crisis económica mundial y futuro de la globalización. Vol. I. 425 p. Colección Análisis Estratégico para el Desarrollo. Juan Pablos Editor. México, D.F. [ Links ]

Denzin, Norman. K. y Lincloln, Yvonna S. (Comps.) 2011. Manual de Investigación Cualitativa. Vol. I. El campo de la investigación cualitativa. Ed. Gedisa. Barcelona, España. 370 p. [ Links ]

Díaz Cervantes, Rufino. 2014. La perspectiva de género en la comprensión de la masculinidad y la sobrevivencia indígena en México. Colegio de Postgraduados, México. Revista Agricultura Sociedad y Desarrollo (ASyD) 11: 359-378. 2014. [ Links ]

Echeverri, R. y Moscardi, E. 2005. Construyendo el desarrollo rural sustentable en los territorios de México. IICA. México, D.F. 283p. [ Links ]

Echeverría, Bolivar. 2013. Modelos elementales de la oposición campo-ciudad. Anotaciones a partir de una lectura de Braudel y Marx. Ed. ITACA. México, D.F. 107 p. [ Links ]

Escobar, Arturo. 2012. Más allá del desarrollo: postdesarrollo y transiciones hacia el pluriverso. Revista de Antropología Social. Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Vol. 21, Págs. 23-62. https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/RASO/article/viewFile/40049/38479 Consulta: 3 de noviembre, 2017. [ Links ]

Escobar, Arturo. 2014. Sentipensar con la tierra Nuevas lecturas sobre desarrollo, territorio y diferencia. Ediciones Universidad Autónoma Latinoamericana-UNAULA. Medellín, Colombia. 184 p. [ Links ]

Foucault, Michel. 1999. Obras esenciales. I. Entre filosofía y literatura, II. Estrategias de poder y III. Estética, ética y hermenéutica. Ed. Espasa Libros. Barcelona, España. 1095 p. [ Links ]

Fowler Salamini, H. y Kay Vaughan, M.(eds).2003.Mujeres del campo mexicano (1850-1990).El Colegio de Michoacán e Instituto de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades de la BUAP. Puebla, Pue.390 p. [ Links ]

Geymonat, Ludovico. 2009. Historia de la filosofía y de la ciencia. Ed. Crítica. Barcelona, España. 738p. [ Links ]

Giddens, Anthony (2000). Un mundo desbocado, los efectos de la globalización en nuestras vidas. México. Taurus. [ Links ]

Giraldo, O. F. 2014. Utopías en la era de la supervivencia. Una interpretación del buen vivir. Universidad Autónoma Chapingo-Sociología Rural-Ed. ITACA. México, D.F. 220 p. [ Links ]

Gómez Funes, Gloria. 2013. Conflicto en las organizaciones y mediación . Universidad Internacional de Andalucía, España. Febrero, 2013. 103 p. http://dspace.unia.es/handle/10334/2558 , Obtenido: 16 de junio, 2017. [ Links ]

Gudynas, Eduardo. 2011. Desarrollo, derechos de la naturaleza y Buen Vivir después de Montecristi. En: Debates sobre cooperación y modelos de desarrollo. Perspectivas desde la sociedad civil en el Ecuador. Gabriela Weber, editora. Centro de Investigaciones CIUDAD y Observatorio de la Cooperación al Desarrollo, Quito. Marzo 2011. pp 83-102. [ Links ]

Gudynas, Eduardo y Acosta, Alberto. 2011. El buen vivir más allá del desarrollo. Qué Hacer No. 181:70-81, marzo, 2011. DESCO, Lima, Perú. Obtenido: 6 de mayo, 2014. https://generoymineriaperu.files.wordpress.com/2013/05/gudynasacostabuenvivirdesarrolloqhacer11r.pdf [ Links ]

Hernández Sampieri, R., Fernández Collado, C. y Baptista Lucio, P. 2014. Metodología de la investigación. McGrawHill Education. México, D.F. 6ª Edición. 600 p. [ Links ]

Hernández-Vela S., Edmundo. 2002. Perspectiva del desarme estratégico. Revista de Relaciones Internacionales de la UNAM, núm. 112, enero-abril de 2012, pp.11-33. [ Links ]

Herrera Tapia, Francisco. 2012. Desarrollo rural en México. Políticas y perspectivas. Ed. MNEMOSYNE. Buenos Aires, Argentina. 157 p. [ Links ]

Hidalgo Flor, Francisco y Márquez Fernández, Álvaro. 2015. Prólogo a la edición mexicana (págs. 9-13) EN: Contrahegemonía y buen vivir. UAM-Xochimilco. México, D.F. 234 p. [ Links ]

Izquierdo Vallina, Jaime. 2013. La conservación cultural de la naturaleza. Red Asturiana de Desarrollo Rural KRK Ediciones. Oviedo, España. 78p. [ Links ]

Latour, Bruno. 2008. Reensamblar lo social. Una introducción a la teoría del actor-red. Ed. Manantial. Buenos Aires, Argentina. 390p. [ Links ]

Leff, E. 2007. Saber Ambiental. Sustentabilidad, racionalidad, complejidad y poder. Siglo XXI Editores. Buenos Aires, Argentina. Libro electrónico, 2011. Consulta: 11 de abril, 2015. http://geoperspectivas.blogspot.mx/2011/02/saber-ambiental-enrique-leff-libro.html [ Links ]

Long, Norman. 2007. Sociología del desarrollo: una perspectiva centrada en el actor. CIESAS-El Colegio de San Luis. México. 504 p. [ Links ]

Márquez, Graciela (coord.) 2014. Claves de la historia económica de México. El desempeño de largo plazo (siglos XVI al XXI). FCE y CNCA. México. 233 p. [ Links ]

Marx, Carlos. 2000. Contribución a la crítica de la economía política. Ediciones Quinto Sol. México. 301 p. [ Links ]

Monfort F. y Guillaumín, A. 1992. Para estudiar el desarrollo. La sociedad perfectiva del siglo XXI. Universidad Veracruzana. Xalapa, Ver. 98p. [ Links ]

Morales Vázquez, B.H. et al. 2015. La epistemología y la metodología, un binomio fundamental para la construcción de la tesis. Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla. Puebla, Pue. 187p. [ Links ]

Moreno, Camila. 2013. Las ropas verdes del rey La economía verde: una nueva fuente de acumulación primitiva. Págs. 63-97. EN: Lang, Miriam; López, Claudia y Santillana, Alejandra. (comps.). 2013. Alternativas al capitalismo/ colonialismo del siglo XXI. Grupo Permanente de Trabajo sobre Alternativas al Desarrollo. Ed. Abya Yala y Fundación Rosa Luxemburgo. Quito, Ecuador.524p. Consulta: 8 de febrero, 2015. http://www.democraciaycooperacion.net/IMG/pdf/Alternativas_al_capitalismo_5022013.pdf [ Links ]

Morin, Edgar. 1994. La noción de sujeto. EN: Fried-Schnitman, Dora (comp.). 1994. Nuevos paradigmas, Cultura y Subjetividad. Editorial Paidós. Argentina. Pp. 67-89. Obtenido: 11 de abril de 2016. http://ahau2012.blogspot.mx/2006/04/nocin-de-sujeto-en-morin.html [ Links ]

Morin, Edgar. 2010. ¿Hacia el abismo? Globalizacion del siglo XXI. Ed. Paidós . Barcelona, España. [ Links ]

Nicol, Eduardo. 2004. La idea del hombre. Ed. HERDER. México, D.F. 493 p. [ Links ]

North, Douglass C. 1993. Instituciones, cambio institucional y desempeño económico. Fondo de Cultura Económica. México. 165 p. [ Links ]

Nussbaum, Martha. C. 2015. Crear capacidades:propuesta para el desarrollo humano. PAIDÓS Ibérica. 272 p. [ Links ]

Oliver, Lucio (responsable). 2013. Gramsci: la otra política. Descifrando y debatiendo los cuadernos de la cárcel. UNAM-Ed. ITACA. México. 111p. [ Links ]

Ortíz, Etelberto.2014. Los falsos caminos al desarrollo. Las contradicciones de las políticas de cambio estructural bajo el neoliberalismo: concentración y crisis. UAM-Xochimilco. México, D.F. 286 p. [ Links ]

Piketty, T. 2014. El capital en el siglo XXI. Fondo de Cultura Económica. México, D.F. 655p. [ Links ]

PNUD, 2015. Panorama general. Informe sobre Desarrollo Humano 2015. Trabajo al servicio del desarrollo humano. Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo. Nueva York, EE.UU. 48 p. http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2015_human_development_report_overview_-_es.pdf Obtenido: 18 de abril, 2016. Págs. 28-31. [ Links ]

PNUD. 2016. Informe sobre Desarrollo Humano 2016. Desarrollo humano para todos. Resumen Ejecutivo. En español. 36 P. Consulta: 15 de abril, 2017. http://www.undp.org/content/undp/es/home/librarypage/hdr/2016-human-development-report.html [ Links ]

Riffo P., L. 2013. Desarrollo Territorial. 50 años del ILPES: evolución de los marcos conceptuales sobre desarrollo territorial. ONU-CEPAL. Santiago de Chile, febrero, 2013. 57 p. http://www.eclac.org/publicaciones/xml/0/49400/S15DT-L3593e_WEB.pdf [ Links ]

Ros Bosch, Jaime. 2015. Grandes problemas. ¿Cómo salir de la trampa del lento crecimiento y alta desigualdad? El Colegio de México y Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. México, D.F. 202 p. [ Links ]

Rubio, Blanca. 2014. El dominio del hambre. Crisis de hegemonía y alimentos. UACh-COLPOS-UIA-Juan Pablos Editor. México, D.F. 270 p. [ Links ]

Sánchez Álvarez, Mauricio; Lazos Chavero, Elena y Melville, Roberto coords. 2012. Riesgos socioambientales en México. CIESAS-México. 223 p. [ Links ]

Sen, Amartya. 2010. Nuevo examen de la desigualdad. Alianza Editorial. Madrid, España. 221 p. [ Links ]

Schmidt, Alfred. 2014. El concepto de naturaleza en Marx. Siglo XXI. México. 244 p. [ Links ]

Toledo, V.M. y Barrera Bassols, N. 2008. La memoria biocultural. La importancia ecológica de las sabidurías tradicionales. Junta de Anadalucía, España e Icaria. Barcelona. 230 p. [ Links ]

Villaveces, José Luis. 2005. Tecnología y sociedad: un contrapunto armónico. Revista de Estudios Sociales no. 22, diciembre de 2005, 49-57. [ Links ]

Wallerstein, Inmanuel et al. 2015. ¿Tiene futuro el capitalismo?. Siglo XXI. México, D.F. 247 p. [ Links ]

Zemelman, Hugo. 1998. Sujeto: existencia y potencia. Rubí, Barcelona; Anthropos, México; Centro regional de Investigaciones Multidisciplinarias-UNAM. 172 p. [ Links ]

Zemelman Merino, Hugo. 2012. Pensar y poder. Razonar y gramática del pensar histórico. Siglo XXI y UNICACH (Chiapas). México, D.F. 188 p. [ Links ]

Žižek, Slavoj. 2011. El espinoso sujeto. El centro ausente de la ontología política. Ed. Paidós, Buenos Aires. Trad. Jorge Piatigorsky. 2da. Edición aumentada. 432p. [ Links ]

1International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank (WB), the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

2Utopia is on the horizon. I walk two steps, utopia takes two steps away and the horizon runs ten steps further. So, what is utopia good for? It serves to walk. Eduardo Galeano (1940-2015) Uruguayan writer and journalist. http://www.proverbia.net/citastema.asp?tematica=364

3Axiology is a branch of philosophy whose purpose is to study the nature or essence of values and value judgments that an indi vidual can make. Therefore, it is very common and frequent that axiology is called the “philosophy of values”. Axiology, along with deontology, form the most important branches of philosophy that contribute to another more general branch: ethics. http://definicion.mx/axiologia/

4Alterity. From Latin, “alteritas”, which is the result of the sum of two components: “alter”, which can be translated as “other”, and the suffix “-dad”, which is used to indicate “quality”. Alterity is the condition of being another. The word alter refers to the “other” from the perspective of “I”. The concept of alterity therefore is used in a philosophical sense to name the discovery of the conception of the world and the interests of an “other”. Alterity must be understood from a division between “I” and “other”, or between “us” and “them”. The “other” has different customs, traditions and representations than “I”: that is why it is part of “them” and not “us”. Alterity implies putting oneself in the place of that “other”, alternating one’s perspective with that of an other’s. That is to say, alterity is a good sign of interest in understanding oneself. Hence, it is responsible for promoting dialogue and agreements and even peace paths to any possible conflict. http://definicion.de/alteridad/

5The panopticon is a building in the form of a brick, which contains cells open to the interior and exterior, in the middle of which there is a patio with a tower in the center from where the guards can see the entire interior of the cells, with no dark places. p. 537. (Foucault, 1999).

Received: January 28, 2018; Accepted: April 05, 2018

texto em

texto em