Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Textual: análisis del medio rural latinoamericano

On-line version ISSN 2395-9177Print version ISSN 0185-9439

Textual anál. medio rural latinoam. n.72 Chapingo Jul./Dec. 2018

https://doi.org/10.5154/r.textual.2017.72.003

Economics and public policies

Socioenvironmental conflicts and open-pit mining in the sierra norte de Puebla, Mexico

1Colegio de Postgraduados - Campus Puebla. Km. 125.5 Carretera Federal México-Puebla, Pue. C.P. 72760. E-mail: bastidas.lina@colpos.mx pjuarez@colpos.mx dcarrera@colpos.mx hvaquera@colpos.mx

2Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Unidad Académica de Estudios Regionales Avenida Lázaro Cárdenas s/n, esquina Felicitas del Río, Jiquilpan Mich. C.P. 59510. E-mail: jcesin@humanidades.unam.mx

The article presents an analysis of the conflict generated by the open pit gold mining projects of Ixtaca and Espejeras, located in the municipalities of Ixtacamaxtitlán and Tetela de Ocampo respectively, which are in the exploration stage and present conflicts with the community. The information was collected by applying a questionnaire to 141 families in four communities. As results, an analysis of the conflicts, in the social and environmental aspects. In addition, the strategies of the mining companies and the groups that reject mining are presented.

Keywords: Gold mining; socioenvironmental conflicts; territorial defense; Ixtacamaxtitlán; Tetela de Ocampo

El artículo presenta un análisis del conflicto generado por los proyectos de minería de oro a cielo abierto de Ixtaca y Espejeras, localizados en los municipios de Ixtacamaxtitlán y Tetela de Ocampo respectivamente, los cuales se encuentran en etapa de exploración y presentan conflictos con la comunidad. El levantamiento de la información se realizó mediante la aplicación de un cuestionario a 141 familias en cuatro comunidades. Como resultados, se muestra un análisis de los conflictos, en los aspectos sociales y ambientales. Además, se presentan las estrategias de las empresas mineras y de los grupos de rechazo a la minería.

Palabra clave: minería de oro; conflictos socioambientales; defensa del territorio; Ixtacamaxtitlán; Tetela de Ocampo

Introduction

Mexico is one of the world’s leading mineral-supplying countries, ranking 17th in total mineral production in 2015, with a value of $209.326 million dollars (Reichl, Schatz, & Zsak, 2017: 32), and was the largest silver producer with an approximate extraction of 5.955 tons (Reichl, et al., 2017: 111). According to the INEGI (2016) in the first decade of this century, mining-metallurgical production grew in real terms at an average annual rate of 3.9 %, exceeding by more than double the growth of the national economy as a whole (1.7 %).

At the same time, the mining concessions have increased; between 2005 and 2014 they went from 22.375 to 25.267 (Secretaría de Economía y Servicio Geológico Mexicano, 2007: 49). According to the Statistical Yearbook of Mining in Mexico, in 2015 there were 267 companies with foreign capital that owned 927 mining projects, 68 % in the exploration stage; 64.2 % of these projects are for extracting gold and silver, 14.2 % polymetallic substances and 12.8 % copper. The foreign companies come mainly from Canada (65 %) and the United States (16 %) (Secretaría de Economía y Servicio Geológico Mexicano, 2015: 20-21).

In addition, the growth of projects and concessions to mining companies has been accompanied by the approval of norms and laws that favor it, which has led to the generation of conflicts. For example, within the normative framework, article 27º of the Constitution was amended in 1992, which states that land and waters within the limits of the national territory can be constituted as private property; article 6º of the Mining Act was also amended in 1992, which decrees that the exploration, extraction and benefit of the minerals or substances referred to in this Act are of public utility, and will be preferential over any other use or exploitation of the land, subject to the con ditions established in it. This puts the communities at a disadvantage, leading the population to a position of legal defenselessness against the private exploitation of their lands, since mining is considered an activity of public utility, causing possible expropriation processes and generating conflict with the livelihoods of the affected communities (Quintana, 2014: 171).

This has been taken advantage of by foreign capital to initiate large mining ventures, usually located in rural communities, resulting in a break with local history and leading to conflicts across all spheres of life that necessarily involve all the social actors (Machado, 2014: 61). Relationships and pre-established linkages are redefined according to those who are against and in favor of mining.

As a result, Mexico has the second highest number of such conflicts (37) in Latin America after Peru, with Puebla and Oaxaca being the states with the highest number of cases (OCMAL, 2016).

The conflicts are scattered throughout Mexico; among the main ones is the environmental disaster that occurred in 2014 in Sonora (Tetreault, 2015: 57), and the conflict with the Canadian company Blackfire in Chicomusuelo, Chiapas (Roblero-Morales, & Hernández-Aguilar, 2012: 75). There are also cases of mining companies that have avoided conflicts by entering into agreements with the communities, as has been the case with the Canadian mining company Goldcorp Inc in Mazapil, Zacatecas, and Ternium in San Miguel Arcángel, Michoacán (Santos-Cordero & Martínez-Silva, 2015: 285).

Specifically for the Sierra Norte of the State of Puebla, the growth policy is based on extractive activities that are accompanied by projects that complement and promote the development of the industry, such as hydroelectric megaprojects that will provide the electric power required by the new mining and oil ventures near the area. The communities where these natural resource extraction projects are located have dubbed them “death projects”, motivating the population to mobilize against them, seeking, among other things, to preserve control of their territories.

The objective of the research was to analyze the current conflicts over two open-pit mining projects, and the struggle strate gies motivated by the socioenvironmental risks that these projects represent in four communities located in the municipalities of Ixtacamaxtitlán and Tetela de Ocampo, Puebla. For the collection of information, 141 surveys were carried out among families located in four communities belonging to the two municipalities under study.

Social perception of socio environmental conflicts

Mining corresponds to an extractive hegemonic economic model, characterized by the appropriation of non-renewable natural resources, use of peasants as the labor force, non-generation of stable productive linkages in the communities, and failure to take into account the community, their livelihoods and their traditions (Delgado-Ramos, 2010: 18, 23). Nevertheless, authors such as Gudynas (2009: 197) mention that there are new models such as neo-extractivism, where companies also appropriate resources associated with global markets, and one of its consequences is increased private accumulation of capital, attracting foreign direct investment that concentrates land and labor in the concession areas. This new model has little productive diversification, and the role of the State is more active through a greater distribution of the surplus generated by extractivism (Gudynas, 2009: 188).

Regardless of whether the model is extractivism or neoextractivism, mining is an activity that deteriorates the environment and generates conflicts and social protests (Gudynas, 2011: 405-406). The feeling that communities have on the extractivist mod el and its characteristics, plus the knowledge of the current conflicts have led the population to reject the new open-pit mining ventures, due to the negative percep tion they have of them.

There is ample evidence of the negative social and environmental impacts of mining projects, leading the mining companies and government to situations of conflict with the communities, sometimes resulting in violence and anti-democratic actions (Gudynas, 2012: 267).

Different types of conflict, such as political, cultural, social, and environmental ones, can be identified. The latter two arise from very different origins, according to the way in which social and environmental conditions are perceived, the assigned valuation, and the implications for the environment of present and future human actions (Gudynas, 2013: 87). They are also the result of social, spatial and temporal patterns of access to the benefits of natural resources that support the life of the com munities (Martínez-Alier, 2010: 358).

The conflicts found in research are framed within those that are related to socioenvironmental impact or the risk thereof (Paz, 2014: 13-14). This is because both projects are in the exploration stage; therefore, the expected threats or risks that probably end in conflicts between the community and the companies that extract the minerals were identified. The fears of future risks perceived by the inhabitants of a space, unfounded or scientifically based, motivate the conflict, although it does not always detonate (Franks et al., 2014: 7578).

The current causes of the conflicts and the threats expected from them were identified from the information gathered in the field, and the future impacts in each area are based on the perception of the respondents. In this study, perceptions are assumed as a social construction of the risks resulting from the action of man; that is, perceptions are the result of cognitive processes that consist in recognizing, interpreting and giving meaning to factors around physical and social experiences, to build a mental organization of their significance and symbolization (Allport, 1974: 7- 8).

For Pidgeon (1998: 5) the perception of risk includes the beliefs, attitudes, judgments and feelings of people, as well as the broader cultural and social dispositions that they adopt towards the threats to the things that they value. Thus, for example, on the land in which the families of the studied communities live, water and the possibility of carrying out agricultural activities are things that they value and are deeply rooted in their ways of life and culture. In this sense, Bickerstaff (2004: 827) argues that perceptions and the response to risks are formed in a context with a variety of social, cultural and political factors.

The perception of environmental risks, that is the environmental risks that surround an individual, is not exclusive to scientific and technical means, but rather it depends on the individuals and the contexts in which they develop (Gudynas, 2004: 123) or from a social construction (Pidgeon, 1998: 6). It is through them that organized frames of reference are formed, which are modified according to life experiences; they come through the senses, and the receivers interpret them according to the circumstances that they lived and experienced (Calixto-Flores & Herrera-Reyes, 2010: 232). This means that the perception will depend on the information held by the social actors which allows them to generate their own expectations.

Open-pit gold mining projects in the sierra norte

Although Puebla is not a gold or silver producer, in 2015 the government granted around 169.320 hectares in 103 mining titles, where the main minerals to be exploited, according to the Sistema de Administración Minera (SIAM), will be gold (18 %), silver (18 %), zinc (16 %), copper (15 %) and lead (13 %) (SIAM, 2016).

In the Sierra Norte de Puebla, exploration activities are underway for two gold, silver and copper mining projects. The Ixtaca project is located in the municipality of Ixtacamaxtitlán, which is in an advanced exploration stage and run by Minera Gavilán, S.A. de C.V., a Mexican subsidiary of Canadian-owned Almaden Minerals. This company discovered in 2010 that there was gold-silver mineralization in the subsoil, with a grade of 2 grams of gold per ton.

In 2012, under the aegis of titles 241003 and 241004 awarded to the company Minera Gavilán S.A. de C.V., valid until the year 2062 and renewable for another 50 years, 55,885 hectares were granted (SIAM, 2016), corresponding to 97.5 % of the authorized area for mining in the Sierra Norte de Puebla.

By 2013, approximately 400 exploratory drill holes had been made, amounting to an estimated 1.35 million proven gold equivalent ounces, 2.18 million indicated ounces and 717 inferred ounces, which led to the formulation of a 14-year mining plan for the Ixtaca project (published on the Almaden Minerals website). Currently, the project is on hold as a result of a constitutional complaint filed by the Tecoltemic ejido in Ixtacamaxtitlán.

The other project, named Espejeras, is being undertaken by the Mexican company Frisco S.A. de C.V., located in Tetela de Ocampo; the company owns 17 mining concessions covering approximately 22,784 hectares. The Minera San Francisco del Oro, S.A. de C.V., a subsidiary of Minera Frisco, S.A. de C.V., holds concessions 166134 and 220980 with 8.75 and 10,663 hectares respectively, located in the community of La Cañada, 5 km from the municipal seat. The mining company was authorized by SEMARNAT (Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales) to perform 27 perforations by reverse circulation and diamond drillings. The project is located in an area with a tradition of underground gold and silver mining; and, since the 1980s, the company has been buying land where there were mines in the past. Currently, the exploration phase is on hold, due to an action undertaken by the Tetela Hacia el Futuro civil movement.

Methodology

This work is a descriptive cross-sectional and deductive-method study. The research technique was a survey of local families. The instruments asked about the struggle strategies against the mining companies, and the different strategies that mining companies have implemented in the study area to inform the community and seek its acceptance. In addition, information was gathered on the socio-economic characteristics of the families, the knowledge the inhabitants have about mining and mining projects, and the community’s perspective.

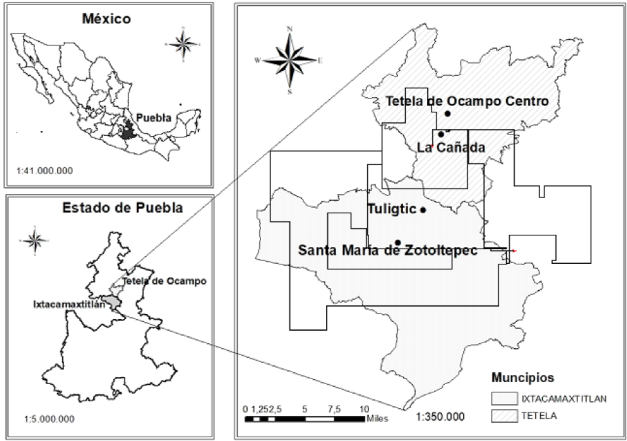

Sample size was obtained by qualitative sampling, with a 95 % confidence interval, 10 % accuracy and 0.09 variance (Rojas, 2013: 298), resulting in a sample size of 141 families, distributed as follows: 29 in Santa María de Zotoltepec, 19 in Tuligtic, 15 in La Cañada and 78 in Tetela de Ocampo Centro, with those surveyed being chosen randomly. Secondary sources on socio-environmental conflicts, perception and resistance movements, as well as research on mining-project problems were also analyzed.

Study area

The research was carried out in the communities of Santa María de Zotoltepec and Tuligtic, located in the municipality of Ixtacamaxtitlán, and Tetela Centro and La Cañada in the municipality of Tetela de Ocampo, in the Sierra Norte de Puebla. In these communities, there are two open-pit gold mining projects in exploration stage. The municipality of Ixtacamaxtitlán has an elevation of between 2,000 and 3,400 m, average annual rainfall of between 600 and 900 mm and an area of 567.96 m2 where 55 % of the land is suitable for agriculture (INEGI, 2009: 2-3). Fodder oats, corn, beans, wheat and alfalfa are sown (INEGI, 2011). In 2010, it had a population of 25,326, of which 24.5 % were indigenous (6,210). In 2015, 80.3 % of the population lived in poverty and 11.7 % in extreme poverty (SEDESOL, 2018).

Tetela de Ocampo has an elevation of between 1,200 and 3,200 m, with an area of 328.8 km2, of which 37 % is for agricultural use and 58 % forest (INEGI, 2009: 2-3). In 2010, it had a population of 25,793, of which 34 % were indigenous. In 2015, 71.6 % of its population lived in poverty and 13.6 % in extreme poverty (SEDESOL, 2018). Figure 1 shows the geographic location of the municipalities within the state of Puebla and the polygons of the mining concessions.

Results and discussion

The mining industry in Mexico appropriates natural resources, sees the peasants as a cheap labor force and does not generate productive linkages in the region, in addition to the negative impacts on the environment that have occurred in the extraction phases (Gudynas 2009: 188 Delgado-Ramos, 2010: 18, 23, Quintana 2014: 171). This dynamic has resulted in an increase in conflicts between the mining companies and the communities where the projects are located, whether they are in the exploration or extraction phase.

In this research, where the projects are in the exploration phase, according to Paz (2014: 13-14), the conflicts found in the communities under study are due to impact risks, since they arise from the fear of the people that mining produces risks that threaten them directly. These fears were classified as social and environmental ones. Below, the current conflicts and those that the inhabitants believe could be created in the future are described.

Social conflicts generated by mining projects in the municipalities under study

The results show that there is a clear perception of conflict in social aspects, which has led the majority of the population of the municipalities under study to be against the development of the mining projects. Table 1 shows the results regarding the acceptance of mining projects in the municipalities under study and their perception in different social variables.

Table 1 Perception of the inhabitants on social conflicts

| Municipality | People who do not agree with the development of a mining industry in their community | People who believe that mining will generate employment | Families that have been adversely affected by mining exploration activities | ||||

| % | Frequency | % | Frequency | % | Frequency | ||

| Ixtacamaxtitlán | 77.1 % | 37 | 75.6 % | 34 | 41.7 % | 20 | |

| Tetela de Ocampo | 95.6 % | 87 | 44.7 % | 38 | 5 % | 4 | |

Source: Data taken from the surveys, 2015

Ixtacamaxtitlán residents perceive that there is an internal division in their community regarding the approval of the arrival of mining in the region. A majority percentage (77.1 %) of those surveyed do not agree with the development of the Ixtaca project, and this is due to the fact that they perceive possible impacts on the environment and human health, which could occur if the extraction phase begins. A similar situation occurred in Ecuador, where one of the main causes of conflict, in the Mirador exploration project, was the division of the population due to the possible dangers that result from the arrival of a mining project, both as a current conflict and as an expected threat (Sánchez-Vásquez, Espinosa, & Aguiguren, 2016: 30). This project covers the indigenous area of the Shuar territory in Ecuador, which presents different social and cultural realities; however, this study is used as background, because the conflicts and impacts analyzed are in the exploration stage, and they are not impacts that have already occurred, as in the cases under study in Mexico.

The other percentage of the population interviewed (22.9 %) said they are in agreement with the possibility of a mining development, since it represents an alternative to the generation of non-agricultural work sources and, possibly, to the activation of the region’s economy. However, they do not consider whether or not there will be socio-environmental or human health impacts. This perception is partly explained by the strategy developed by Almaden Minerals, by making promises about job creation, offering contributions to the health system, schools, housing, social events, and the construction of recreational areas, and by helping to improve the region’s economy through tax revenues that will be received by the municipality. A study conducted on the conflict between the community of Salaverna, in Zacatecas, and the Frisco company shows this behavior. Here the company takes advantage of the internal division of the community to fragment the population’s opinions, seeking to weaken any collective action against a possible relocation of the town (Uribe-Sierra, 2017: 93). This same behavior is evidenced in the research conducted by Roblero-Morales and Hernández-Aguilar (2012: 80-81) in Chicomusuelo, Chiapas, where the Canadian company Blackfire acquired 13.5 hectares with deception, promising infrastructure improvements, public services, economic benefits for the community and job creation, promises that were not fulfilled, a fact that led to conflict with the community.

In this context, Garibay and Balzaretti (2009: 93) state that mining companies approach the population with a veil of social kindness, granting them a business charity treatment for their economic conditions, but not a negotiation on a deal where they seek to associate with them, which suggests that it is a practice of domination. Therefore, mining companies encourage confrontation within the community as a strategy to be accepted.

The fact that personnel working on the projects (Ixtaca and Espejeras) enter the privatelyowned lands of the community’s inhabitants without authorization from their owners, to carry out marking work on the land and even to carry out exploration activities, has also been a cause of conflict. In Ixtacamaxtitlán, of the 41.7 % of respondents who said they were adversely affected by exploration activities, 33 % of them stated that their land had been invaded, while in Tetela de Ocampo only one family said this had occurred. In Ixtacamaxtitlán, they only asked for permission the first time they entered the property and even paid an amount of money according to the activity they carried out; in subsequent visits to the properties, they no longer requested authorization, a fact that caused annoyance in the community. For its part, the Frisco company (Tetela de Ocampo), by fencing off the land it acquired, closed the commu nal roads, impeding access to nearby land.

Rappo-Miguez, Vázquez-Toriz, Amaro-Capilla, and Formacio-Mendoza (2015: 208) mention that these conflicts have worsened the land dispute between the community and the mining companies in the Sierra Norte de Puebla, and that there are only two ways out of the situation: either the mining companies achieve control over the territory and displace the inhabitants, or the community retains control over its lands and impedes the mining development in the region. However, it should be borne in mind that the land where the two mining projects under study will be developed is owned by the exploration companies, which acquired it legally through purchase processes arranged with the previous owners; this could lead the mining companies to continue negotiating with a part of the population that owns land found in the mining concessions.

Residents’ fears of social impacts

Ixtacamaxtitlán and Tetela de Ocampo residents perceive similar social impacts, with 25.5 % of the respondents having the perception that, with the arrival of a predominantly male population and the rise in purchasing power in the region, drug and alcohol use will increase, leading to increased insecurity. Sánchez-Vásquez et al. (2016: 30), in a study on the Mirador mining exploration project, also found these causes as potential threats perceived by the population due to a possible mining development.

This fear is evident in the population due to the experiences lived in other regions that have mining extraction, where the arrival of this industry has increased social problems in the community. Gibson and Klinck (2005: 122) found in indigenous communities in northern Canada, with mining developments in their territory, an increase in drug and alcohol use associated with the higher income generated by mining. They also found that social changes in that region of Canada increased the rate of violent crimes. Although northern Canada compared to the Sierra Norte de Puebla presents different realities, for this analysis the study is taken as an antecedent of this specific community fear that can become a negative social impact.

Another social fear is population mobility; that is, the establishment of outsiders in the region whose settlements will promote the displacement of the original population to other regions. This fear was expressed by 27.6 % of the respondents. Sánchez-Vásquez et al. (2016: 31), in their study of the Mirador Project, found results similar to those of this research, and relate the migratory phenomenon with the risk of increased crime, prostitution, drug and alcohol dependence and violence in the new mining areas. On the other hand, Garibay, Boni, Panico, y Urquijo. (2014: 139) describe the experience of the Mazapil, Zacatecas region where migration was encouraged since the company preferred to hire non-local personnel with technical studies and experience in handling machinery.

As background, a negative social impact experience in Latin America is analyzed by Bury (2007: 385) , who mentions that the MYSA mining company in Cajamarca, Peru, has attracted people from other regions of the country who are trained in specialized mining areas. Of the 90 % of Peruvian personnel hired, only 44 % were from the Cajamarca region, and the families that did not manage to obtain employment migrated to Lima or coastal cities. These migrations to mining regions and the migration of peasants to other places occur because mining companies recruit trained and experienced personnel.

It is important to mention that foreign migrants form enclaves and new economic and social networks; transforming the region economically, socially and culturally. It means that the peasants are losing control over decision-making related to their territories. In general, the perception of the social impacts generated by mining is predominantly negative, and the current conflicts have led to internal division of the communities among the majority of the inhabitants.

Pidgeon (1998: 6) suggests that the risks of social conflicts are not only due to information received by the community or outsiders, but may reflect commitments to the most fundamental values with which particular groups identify themselves. Examples include the disunity of the population faced with the phenomenon of mining in the region, or even the uneasiness due to the mere fact of knowing that people will come from the region around and even from different parts of the country.

Current environmental conflicts

Regarding environmental conflicts, they occur mainly in relation to the availability and quality of water, being isolated and of low impact in the exploration stage.

In Santa María de Zotoltepec, Ixtacamaxtitlán, two incidents of water damage were found: one involved the elimination of a water source and the other was the death of backyard animals belonging to two families. Another negative effect, according to the people consulted, was the drying up of local springs as a result of the drilling carried out by the Ixtaca project, affecting two families. In this case the water was used for irrigation; the problem is aggravated because this area has low rainfall. It is considered that Almaden Minerals committed irregularities in the exploration, since it drilled more than the 163 drill holes authorized by SEMARNAT and to a greater depth, between 325 and 701 meters on average, than the location of the aquifers, which range from 158.8 to 196.15 meters (PODER, Atcolhua, IMDEC, & Cesder, 2017: 100-101).

In relation to the animal deaths that occurred in the community of Santa María, the people who investigated claimed that it happened because the animals drank water that came out of the plant where the material extracted from exploration was treated. The plant is located on the edge of town, and its wastewater is dumped into the tributary where the community has its sewage. Although there is no toxicity study of the tributary, the peasants say that their animals had never died from watering near this tributary. However, Astete, Gastañaga and Pérez (2014: 700- 701) conducted an environmental impact study on the Las Bambas project in Peru; after five years of mining exploration, they found no negative environmental impact in relation to heavy metal exposure in the area of influence.

Fears of environmental impacts

Concerning environmental fears, Table 2 presents the results obtained on the perception of the inhabitants in this regard.

Table 2 Perception of the inhabitants on environmental conflicts

| Municipality | People who believe that mining will affect their drinking water | People who believe that a disaster could occur in the municipality due to mining | People who think that mining will pollute the environment | People who think that mining will bring diseases | ||||

| % | Frequency | % | Frequency | % | Frequency | % | Frequency | |

| Santa María de Zotoltepec | 79.3 % | 23 | 93 % | 26 | 75.9 % | 22 | 85.7 % | 24 |

| Tuligtic | 94.7 % | 18 | 100 % | 19 | 100 % | 19 | 94.7 % | 18 |

| La Cañada | 80 % | 12 | 67 % | 10 | 91.7 % | 11 | 80 % | 12 |

| Tetela de Ocampo centro | 98.7 % | 77 | 99 % | 75 | 97.4 % | 76 | 94.9 % | 74 |

Source: Data obtained from the surveys, 2015

In the event that mining projects are developed in any of the municipalities under study, an average of 91.4 % of the respondents fear negative effects and insist there will be a pollution impact and water scarcity in the region. The fear is more marked in Tetela de Ocampo Centro with 98.7 % of respondents believing that there will be an impact on water resources, while in Santa María this proportion is 79.3 % and in La Cañada 80 %; in the latter two is where the mining projects are located. Ixtacamaxtitlán residents fear that when the tailings dam is built, the water resource will be dramatically depleted. It can be said that their fears are well-founded since this happened in the Peñasquito mine in Zacatecas, where Goldcorp Inc used almost all the water in the region, and to achieve this it bought the lands rich in groundwater and obtained a concession of up to 35 million annual cubic meters of water. This action led to overexploitation of the aquifers, generating a negative water balance and thus causing water shortages that affected various communities (Garibay, et al., 2014: 126). The population’s perception of danger is that of losing a vital resource for life. As Gudynas (2013: 87) points out, the conflict with regard to water arises from the high valuation that the inhabitants assign to the resource, since water is fundamental to carry out the current and future human (agricultural and survival) actions of the communities.

At least 90 % of the respondents believe that there is a possibility of a disaster occurring due to the tailings dam and they give as an example the case of the Grupo México-affiliated Buenavista del Cobre mine in Sonora, considered to be the worst environmental disaster in the country’s mining history, when 40,000 m2 of sulfuric acid spilled into the Tinajas stream in Cananea on August 6, 2014 (Alfie-Cohen, 2015: 105), endangering the lives of 24 thousand people (Tetreault, 2015: 58). Despite legal requirements, current technology and safety plans adopted by mining companies, there is no guarantee for the community that environmental disasters will not occur.

Of the people surveyed, 91.2 % considered that mining brings with it environmental pollution; this includes water, air and land pollution, which results in decreased crop yields. Castro, Zapata-Martelo, Pérez Olvera, and Martínez Corno (2015: 291), in a study conducted in the Cedros ejido in "Zacatecas, found that agricultural production declined as a result of mining activity. In addition, the new houses for the families that were relocated were not adapted to their needs since they do not have a space for backyard activities, which are culturally and nutritionally important, and the conditions of the land make it practically useless for planting crops; moreover, the scarcity and very poor quality of water does not al- low any form of life.

Another latent fear expressed by an average of 88.8 % of those surveyed focused on the possible emergence of diseases that they do not currently suffer from; they mentioned that the diseases that may arise are dermatological (84 %), respiratory (72 %), gastrointestinal (61 %), brain dam- age (35 %) and cancer (16 %), as a consequence of mining. This result is consistent with the study carried out on the Mirador project, where Sánchez-Vásquez et al. (2016: 31) stress that diseases are one of the factors within the perception of threats expected by the inhabitants. In Nuevo Peñasquito, a town near the Peñasquito mine in Zacatecas, the environmental deterioration has increased health problems (Castro et al., 2015: 292). It can be said that the perception among those surveyed arises from facts that the population knows about other mining areas.

The threats of conflict among the respondents appear mainly due to the perception they have of the impacts to the environment and their health, externalities that the mining companies do not internalize, and which are difficult to value. In this sense, Martínez-Alier (1998: 115) argues that eco logical economics still cannot assess the uncertainties and irreversible contingencies that might occur in exploitation and processing activities, and even if the externalities could be valued in market terms, it is not possible to put a value on the risk that people take by accepting mining projects in their region, nor the social costs. Given this, the people consulted from the communities under study believe that these uncertainties and contingencies, even if they were valued, will never be paid by the mining companies.

The negative perception of open-pit mining projects has been developed on the basis of external information that alerts the population to the social and environmental danger of this industry, especially about the experiences lived in mining areas. The media, family members, organizations and even mining companies provide information to the community, with which they have generated their own expectations, as explained by Calixto-Flores and Herrera-Reyes, (2010: 232).

Strategies of conflict actors

The main strategy deployed by the communities is internal organization, forming defense groups. In Ixtacamaxtitlán, in 2013 the Atcolhua group was formed, and in Tetela de Ocampo the Tetela Hacia el Futuro group was legally constituted; both groups were born out of people’s concern for adverse water, environmental and health impacts. The defense groups have joined different social movement networks such as the Tiyat Tlalit Council and the Red Mexicana de Afectados por la Mineria (Mexican Network of People Affected by Mining, REMA for its initials in Spanish), among others. They have also designed information and media plans, which have promoted “no to mining” in the community, making the conflict visible outside the region.

Environmental movements can be seen as the expression of (some) non-internalized externalities (Martínez-Alier, 1998: 113), as the rejection voice of communities to assuming the costs of the negative impacts of mining, and not having a fair payment for this. In this regard, Madrigal (2013: 129) considers that the visibility of conflicts turns the environmental impact risks into a social problem.

The type of conflict between the mining companies and the population of both municipalities under study, according to the Gudynas conflict typology (2013: 90) , can be defined as a medium-intensity conflict, since the complaints have already gone from the private to the visible domain, and social networks have been formed for the cause, but there are still no cases of physical violence.

Another strategy has been the cultural appropriation of the territory, through pilgrimages and rites, which combine the Catholic with the pre-Hispanic. This is how the struggles have led to the cultural appropriation of the environment and to rediscovering the territory, redefining the space and giving it a new meaning (Milesi, 2012: 53).

The defense groups and the opinion-expression strategies have contributed to the creation of a social, cultural and political environment that has allowed people to form a positive or negative perception of the mining projects in the area.

For their part, the mining companies have implemented different strategies to position the project in the community. On the one hand, Almaden Minerals has decided, in the exploration stage, to approach the population through a social plan, investment in medical equipment, improvements in physical infrastructure and support to educational institutions. The support has been granted to various communities, but the main beneficiaries have been the inhabitants of Santa María. In order to gain acceptance from the community close to the mine, they have used their employees and their families to influence the population that is against it. In addition, they have made promises to improve the quality of life in the municipality once the mining begins.

The Frisco mining company has used governmental influences and intimidation as a tool for rapprochement in Tetela de Ocampo; the Espejeras project managers have communicated directly and through public entities with the community leaders. It offers the creation of 630 jobs and a social plan when the mine is in operation. Despite this, the community considers that it does not need the hospitals and educational institutions that they promise.

The study carried out by Madrigal (2013: 130) at Minera San Xavier in San Luis Potosí analyzes the strategies carried out by the New Gold mining company, which highlights the negotiation with the state government to form a coalition of interests, defining the conflict in terms of job creation and economic benefits for the region, through a local mass media advertising strategy. In these cases, the imposition of the strongest is played out, and it is the companies that have advantages over the communities, from the legal point of view, with the government in their favor, with the possibility of lobbying, and with financial resources available to invest in actions leading to the community’s acceptance of the mining projects.

Conclusions

The conflicts generated by mining companies are a consequence of the neo-liberal and globalizing policies that have increased the concentration of capital, and have historically stripped the inhabitants of the lands where the mining takes place. Conflicts between the communities and the mines in operation, especially in Latin America, have led people to fear social and environmental impacts that are harmful to the communities under study. In part, this has contributed, in this study case, to conflictive relations between the communities and the mining companies, which are in the exploration phase. The communities perceive the mining industry as environmentally devastating, with more legal and political support from the government than they have.

The current conflicts are not based on illegal land grabs because both companies have bought the land, where the future extraction would be, under formal negotiations. Fears about the environment and social issues are framed by the demand for social and environmental justice rather than redistributive justice.

However, there are fears, especially about the impact on the water resource and the health of the population, which cause it to enter into a conflictive relationship with the mining companies that wish to exploit their territory. This has led the mining companies to design a series of mechanisms to approach the community. On the other hand, the opposing population has organized itself into social movements, strengthening itself through the creation of networks and the construction of social capital.

The arrival of the mining projects in the region has generated in the population a form of social organization that they had not previously experienced; likewise, they have had to deal with the division within the community and the families themselves, between those who disagree and those who seek their own individual welfare. These divisions of opinion have been more marked in Ixtacamaxtitlán, and have affected traditional social processes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the National Science and Technology Council for the support re ceived through the PhD scholarship granted to the first author.

REFERENCES

Alfie-Cohen, Miriam. 2015. “Conflictos socio-ambientales: la minería en Wirikuta y Cananea”. El Cotidiano (191): 97-109. [ Links ]

Allport, Floyd. 1974. El problema de la percepción. Buenos Aires. Nueva Visión. [ Links ]

Astete, Jonh, María Gastañaga y Doris Pérez. 2014. “Levels of heavy metals in the environment and population exposure after five years of mineral exploration in the Las Bambas project, Peru”. Revista Peruana de Medicina Experimental y Salud Pública 31 (4): 695-701. [ Links ]

Bickerstaff, Karen. 2004. “Risk Perception Research: Socio-Cultural Perspectives on the Public Experience of Air Pollution”. Environment International 30 (6): 827-40. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2003.12.001. [ Links ]

Bury, Jeffrey. 2007. “Mining Migrants: Transnational Mining and Migration Patterns in the Peruvian Andes”. The Professional Geographer 59 (3): 378-389. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9272.2007.00620.x [ Links ]

Calixto-Flores, Raúl, and Lucila Herrera-Reyes . 2010. “Estudio sobre la percepción y la educación ambiental.” Tiempo de Educar 11 (22): 227-49. [ Links ]

Castro, Gabriel, Emma Zapata Martelo, María Pérez Olvera y Guadalupe Martínez Corno. 2015. “Desposesión, Minería y Transformaciones en la Vida de la Población de Cedros, Zacatecas, México”. Oxímora Revista Internacional de Ética y Política (7): 276-299. [ Links ]

Delgado-Ramos, Gian. 2010. “Ecología política de la minería en América Latina. Aspectos socioeconómicos, legales y ambientales de la mega minería”. Ciudad de México: Centro de Investigaciones Interdisciplinarias en Ciencias y Humanidades. [ Links ]

Franks, Daniel M, Rachel Davis, Anthony J Bebbington, Saleem H Ali, Deanna Kemp, and Martin Scurrah. 2014. “Conflict Translates Environmental and Social Risk into Business Costs.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111 (21): 7576-7581. doi:10.1073/pnas.1405135111. [ Links ]

Garibay, Claudio y Alejandra Balzaretti . 2009. “Goldcorp y la reciprocidad negativa en el paisaje minero de Mezcala, Guerrero”. Desacatos 30: 91-110. [ Links ]

Garibay, Claudio, Andrew Boni, Francesco Panico y Pedro Urquijo. 2014. “Corporación minera, colusión gubernamental y desposesión campesina. El caso de Golcorp Inc. en Mazapil, Zacatecas”. Desacatos 44:113-142. [ Links ]

Gibson, Ginger y Jason Klinck . 2005. “Canada’s Resilient North: The Impact of Mining on Aboriginal Communities Understanding the Industry: Mining Characteristics”. Pimatisiwin: A Journal of Aboriginal and Indigenous Community Health 3(1): 115-139. [ Links ]

Gudynas, Eduardo. 2004. Ecología, economía y ética del desarrollo sostenible. Montevideo: CLAES y D3E. [ Links ]

Gudynas, Eduardo. 2009. “Diez tesis urgentes sobre el nuevo extractivismo. Contextos y demandas bajo el progresismo sudamericano actual”. En Extractivismo, Política y Sociedad, editado por VVAA, 187-225. Quito: CAAP y CLAES. [ Links ]

Gudynas, Eduardo. 2011. “Más allá del nuevo extractivismo: transiciones sostenibles y alternativas al desarrollo.” En El Desarrollo En Cuestión. Reflexiones Desde América Latina, editado por Fernanda Wanderley, 379-410. La Paz: Oxfam y CIDES UMSA. [ Links ]

Gudynas, Eduardo. 2012. “Sentidos, opciones y ámbitos de las transiciones al postextractivismo”. En Más allá del desarrollo, 265-298. Quito. Grupo Permanente de Trabajo sobre Alternativas al Desarrollo. [ Links ]

Gudynas, Eduardo. 2013. "Conflictos y extractivismos: conceptos, contenidos y dinámicas”. Decursos. Revista de Ciencias Sociales 15 (27-28): 79-116. [ Links ]

INEGI. 2009. Prontuario de información geográfica municipal de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos. http://www3.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/mexicocifras/datos-geograficos/21/21172.pdf [ Links ]

INEGI. 2011 México en cifras. Ixtacamaxtitlán, Puebla. http://www3.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/mexicocifras/default.aspx?e=21 [ Links ]

INEGI. 2016. Sistema de Cuentas Nacionales de México económica. http://www.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/bie [ Links ]

Machado, Horacio. 2014. “Territorios y Cuerpos en Disputa: Extractivismo minero y ecología política de las emociones”. Revista Sociológica de Pensamiento Crítico 8 (1): 56-71. [ Links ]

Madrigal, David. 2013. “La naturaleza vale oro Propuesta analítica para el estudio de la movilización social en torno a la minería canadiense en San Luis Potosí”. Revista Del Colegio de San Luis (5): 114-133. [ Links ]

Martínez-Alier, Joan. 1998. Curso de Economía Ecológica. México D.F.: Editado por Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Medio Ambiente Oficina Regional para América Latina y el Caribe. [ Links ]

Martínez-Alier, Joan. 2010. El ecologismo de los pobres. Conflictos ambientales y lenguajes de valoración. Cuarta edición. Lima: Espiritrompa Ediciones. [ Links ]

Milesi, Andrea. 2012. “De recursos naturales a bienes comunes: la minería a cielo abierto”. Avá. Revista de Antropología 20: 33-56. [ Links ]

OCMAL - Observatorio de Conflictos Mineros de América Latina. 2016. Base de datos de conflictos mineros en México. http://basedatos.conflictosmineros.net/ocmal_db/?page=lista&idpais=02024200 [ Links ]

Paz, María F. 2014. “Conflictos socioambientales en México: ¿qué está en disputa?”. En Conflictos, conflictividades y movilizaciones socioambientales en México: problemas comunes, lecturas diversas, editado por María Fernanda Paz y Nicholas Risdell 91-110. Cuernavaca: MAPorrúa. [ Links ]

Pidgeon, Nick. 1998. “Risk Assessment, Risk Values and the Social Science Programme: Why We Do Need Risk Perception Research”. Reliability Engineering and System Safety 59: 5-15. [ Links ]

PODER, Atcolhua, IMDEC y Cesder. 2017. Minería canadiense en Puebla y su impacto en los derechos Humanos. Por la vida y el futuro de Ixtacamaxtitlán y la cuenca del río Apulco. Puebla. [ Links ]

Quintana, Roberto. 2014. “Actores sociales rurales y la nación mexicana frente a los megaproyectos mineros”. Problemas del Desarrollo, 45 (179): 159-180. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-7036(14)70145-2 [ Links ]

Rappo-Miguez, Susana, Rosalía Vázquez-Toríz, Mirisela Amaro-Capilla y Xóchilt Formacio-Mendoza. 2015. “La disputa por los territorios rurales frente a la nueva cara del extractivismo minero y los procesos de resistencia en Puebla, México”. Revista NERA, 18 (28): 206-222. [ Links ]

Reichl, Christian; Peer Schatz and G. Zsak. 2017. World Mining Data; volumen 32. Viena. International Organizing Committee for the World Mining Congresses. http://wmc.org.pl/sites/default/files/WMD2017.pdf [ Links ]

Roblero-Morales, Marín y Gerardo Hernández-Aguilar. 2012. El despertar de la serpiente. La minería en la Sierra Madre de Chiapas. Revista de Geografía Agrícola, (48-49): 75-88. [ Links ]

Rojas, Raúl. 2013. Guía para realizar investigaciones sociales. México: Plaza y Valdés Editores. [ Links ]

Sánchez-Vázquez, Luis, María Espinosa y María Eguiguren. 2016. “Percepción de conflictos socio-ambientales en zonas mineras: el caso del proyecto Mirador en Ecuador”. Ambiente & Sociedade 19 (2): 23-44. [ Links ]

Santos-Cordero, Blanca y Eleocadio Martínez-Silva. 2015. “El “consentimiento” negociado entre dos comunidades mineras mexicanas y las trasnacionales Goldcorp y Ternium”. Región y Sociedad 27 (64): 285-311. [ Links ]

Secretaría de Economía y Servicio Geológico Mexicano. 2007. Anuario estadístico de la minería mexicana 2006. http://www.sgm.gob.mx/productos/pdf/Anuario_2006.pdf [ Links ]

Secretaría de Economía y Servicio Geológico Mexicano. 2015. Anuario estadístico de la minería mexicana 2015, edición 2016. http://www.sgm.gob.mx/productos/pdf/Anuario_2015_Edicion_2016.pdf [ Links ]

SEDESOL. 2018. Informe anual sobre la situación de pobreza y rezago social 2018. Puebla. Ixtacamaxtitlán. https://www.extranet.sedesol.gob.mx/pnt/Informe/informe_municipal_21083.pdf; [ Links ]

SEDESOL. 2018a. Informe anual sobre la situación de pobreza y rezago social 2018. Puebla. Tetela de Ocampo. https://www.extranet.sedesol.gob.mx/pnt/Informe/informe_municipal_21172.pdf [ Links ]

SIAM - Sistema de Administración Minera. 2016. Cartografía minera. http://www.cartografia.economia.gob.mx/cartografia/ [ Links ]

Tetreault, Darcy. 2015. “El peor desastre ambiental”. En Megaminería, extractivismo y desarrollo económico en América Latina en el siglo XXI. Editado por Rodolfo García, 57-67. Zacatecas. MAPorrúa. [ Links ]

Uribe-Sierra, Elías. 2017. Salaverna (México): “Un conflicto entre el despojo territorial y el arraigo minero de la población”. RIVAR3 (10): 92-109. [ Links ]

Received: March 13, 2018; Accepted: May 17, 2018

text in

text in