INTRODUCTION

The growth of the human population and the associated productive activities have created a mixed landscape with land uses at different scales. This mosaic of productive activities and natural vegetation areas creates scenarios where multiple interactions between humans and wildlife occur (Madden 2004, Lamarque et al. 2009). From a human perspective, some of these interactions are positive and others are negative. Interactions that are perceived negatively are referred to as human-wildlife conflicts (HWC, Inskyp and Zimmerman 2009), where the outcome of these interactions have negative effects, either real or perceived, that produce a corresponding human reaction that can result in possible harmful impacts on wildlife individuals and/or populations (Morzillo et al. 2014).

Certain factors that promote the emergence of HWC relate to habitat transformation and the associated reduction of resources available for wildlife (Cupul-Magaña et al. 2010, García-Grajales 2013, García-Grajales and Buenrostro-Silva 2013). This transformation is mainly associated with the expansion of human productive activities as well as indirect factors, such as floods, fires, climate change, and others (Lamarque et al. 2009).

As the future of many wildlife populations depends on their capacity to coexist with humans, HWC represent a growing global challenge in terms of wildlife conservation (Treves et al. 2006). In Mexico, inadequate management of HWC has caused the extinction in the wild of the Mexican wolf (Canis lupus baileyi), the grizzly bear (Ursus arctos horribilis) (Ceballos and Simonetti 2002), the Guadalupe caracara (Polyborus lutosus,Greenway 1967), and it has caused the local extinctions of a number of feline species (Hoogesteijn et al. 2016).

From a social perspective, conservation policies that impose restrictions on the use of natural resources, a lack of economic alternatives and HWC are among the main problems affecting wildlife conservation, and inadequate treatment of these interactions can thus generate different types of social problems (Baynham-Herd et al. 2018). These problems can emerge when local populations perceive that the needs and/or value of the wildlife are being favored over their own necessities, or when local organizations and the affected individual are inequitably empowered to deal with HWC, or when conservation policies restrict the harvesting of vital commonly used natural resources. Human-human conflicts can emerge when different groups of people do not agree on management policies that are directed towards conflictive wildlife (Hill 2004, Madden 2004, Marchini 2014); this situation occurs in Natural Protected Areas (NPA) which are one of the main government strategies in Mexico for conserving the environment and the associated services it provides to society (Bezaury-Creel and Gutiérrez-Carbonell 2009). For all the aforementioned reasons, we reviewed any works related to the analysis of HWC, in order to assess and synthesize the current status of knowledge in Mexico. We focused on several questions. Firstly, what is the state of the art of HWC in Mexico? Secondly, which wildlife species have been studied the most? Thirdly, where have these interactions been studied and what information exists for NPA? Finally, what are the existing gaps in knowledge concerning the study of HWC?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A web search was implemented to locate scientific articles, scientific outreach broadcasts, books, reports, congressional acts, and theses between 1983 and 2017. Using the methodology devised by Inskyp and Zimmermann (2009), we searched for documents where the abstract included certain keywords, or the title included phrases or words related to HWC. We began by searching for negative wildlife-human conflict and human-wildlife interactions. Subsequently and one at time, we then added terms related to negative interactions, such as harm and/or attacks and/or impacts with the potential to affect crops and/or cattle and/or poultry and/or people. This was undertaken in both English and Spanish. Once the search results were obtained, we reviewed any literature cited, by searching for the same words or phrases.

From all the documents obtained, we selected any studies performed in Mexico and extracted information related to research themes, the involved species, the location of the studied sites, and also the institutions to which authors were affiliated with. All the publications were cataloged according to their research focus: cattle and poultry damage, human health damage, and HWC and their impact on biodiversity conservation.

In order to register our results, we used the original scientific names in the publications, but later these were updated using the latest taxonomic nomenclature. We considered the species that were mentioned in the publications, in order to quantify the species studied, whether or not they were the main research focus. Then we mapped the location of the reported study sites, using the digital cartography available in Google Earth and subsequently overlapped the available layers of federal NPA in SEMARNAT-CONANP (2017) and the state, municipal, private, and communal protected areas in CONABIO (2015), using ArcMap 10.3 to superimpose the layers of information and generate the resulting cartography.

RESULTS

General trends

A total of 70 publications were found, related to the study of HWC in Mexico. Of the publications that were analyzed, 41.4% were scientific articles, 20% were technical reports, 18.6% were theses, 11.4% were congress memoirs, 4.3% were national and regional government reports, 2.8% were book chapters, and 1.4% were scientific outreach broadcasts.

Most of the publications we encountered that dealt with HWC focused on the description of negative events (35.7%), their quantification (24.3%), the construction of theoretical frameworks (15.7%), human perception analyses (14.3%), and the identification of the species responsible for the interaction (10%). Most of the HWC research in Mexico was carried out in 2010, 2013, and 2014, and was mainly directed towards studies on felines and crocodiles.

Type of damage

The available publications were mostly related to negative events with cattle and/or poultry (32.8%), humans (27.1%), crops (24.3%), and a mixture (15.7%). The studies that analyzed crop damage by wildlife were mostly published in 2012 (three studies); the first publication regarding negative events on cattle and/or poultry was in 2000 and afterwards it was a recurring theme in 2011 and 2013, with four publications produced each year that regularly studied wild felines, particularly jaguars (Panthera onca). Regarding human health studies, the first publication appeared in 1996 and since then they have continued to multiply. The majority of these studies are related to reports on crocodile attacks in 2013 and 2014, that are cited in the publication of the already mentioned National Protocol by SEMARNAT.

Crop damage

Studies on crop predation were mostly directed towards quantifying damage and evaluating the economic losses, identifying the species responsible for damage, and analyzing the farmer's perception. Other studied themes included field spatial descriptions of crops damaged, the seasonality and temporality of attacks, and the exploration of alternatives to mitigate or diminish these conflicts.

A total of 66 species were cited as responsible for HWC (44 birds and 22 mammals). The species that were mentioned the most often were; white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus, 8 mentions); raccoon (Procyon lotor, 7 mentions); coati (Nasua narica, 6 mentions); collared peccary (Dicotyles tajacu, 5 mentions); gopher (Cratogeomys merriami, 4 mentions); and the Mexican grey squirrel (Sciurus aureogaster, 4 mentions). Significantly, even though the white-tailed deer is the most commonly mentioned species, some authors have pointed out that they actually cause less damage compared to raccoons, coatis, and peccaries.

However, other factors can cause more damage than wildlife, such as rain (excess or lack of), wind, fires, soil type, and crop management.

Cattle and poultry damage

Studies about this kind of damage, mainly focused on describing events, analyzing perceptions, constructing theoretical frameworks, and quantifying negative events. A total of 28 species were cited as responsible for this damage (4 birds, 20 mammals, and 4 reptiles). The most commonly mentioned species were; cougar (Puma concolor, 19 mentions); jaguar (P. once, 18 mentions); coyote (Canis latrans, 7 mentions); jaguarundi (Herpailurus yagouarondi, 7 mentions); gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargeteus, 7 mentions); black bear (Ursus americanus, 4 mentions); and ocelot (Leopardus paradalis, 4 mentions).

Human health damage

Concerning the analyses of these negative events, those that refer to damage by crocodiles predominated, followed by the construction of theoretical frameworks and the analysis of perceptions. Among the documents reviewed, 23 species (1 mammal, 1 amphibian, and 21 reptiles) were reported to have caused damage and/or were perceived to be of risk. The species most often mentioned as being involved in this conflict were; the American crocodile (Crocodylus acutus, 14 mentions); (Crocodylus moreletti, 4 mentions); Mexican jumping viper (Atropoides nummifer, 2 mentions); Eastern milksnake (Lampropeltis Triangulum, 1 mention); Mexican Pacific lowlands garter snake (Thamnophis valida, 1 mention); common caiman (Caiman crocodiles, 1 mention); rattlesnake (Crotalus durissus, 1 mention); Bell's False Brook Salamander (Itshmura belli, 1 mention); and cougar (P. concolor, 1 mention).

HWC and their impact on biodiversity conservation

A total of 112 species of birds, mammals, amphibians, and reptiles were mentioned as being responsible for damaging crops, livestock, poultry, and human health. Of these, nine species represented 41% of the total mentions, indicating the high level of attention that is given to them (P. onca, P. concolor, C. acutus, N. narica, O. virginianus, C., H. yagoauroundi, P. lotor, and U. cynereoargenteus). The species that were identified as the most harmful were 48 birds (42.8%), 41 mammals (36.6%), 1 amphibian (0.9%), and 22 reptiles (19.6%).

Of the total number of species mentioned, 33 (29.5%) are in some risk category according to the Mexican Norm of Endangered species. A number of bird species are subject to special protection: aztec parakeet (Eupsittula nana sp. astec), pale billed woodpecker (Campephilus guatemalensis), sandhill crane (Antigone canadensis), and Montezuma oropendula (Psarocolius montezuma). At risk of extinction is the ornate hawk-eagle (Spizaetus ornatus) and the muscovy duck (Cairina moschata). Mammals that are subject to special protection include the cacomistle (Bassariscus sumichrasti), threatened greater grison (Galictis vittata), jaguarundi (Herpailurus yagouarondi), long-tailed otter (Lontra longicaudis), and kit fox (Vulpes macrotis). Mammals in danger of extinction are tayra (Eira barbara), ocelot (Leopardus pardalis), margay (Leopardus wiedii), and jaguar (P. onca), and one species that is possibly extinct in its wildlife habitat is the wolf (Canis lupus). For reptiles, those that are subject to special protection are Mexican cantil (Agkistrodon bilineatus), spectacled caiman (Caiman crocodilus), American crocodile (Crocodylus acutus), western diamond-back rattlesnake (Crotalus atrox), South American rattlesnake (Crotalus durissus), northern black-tailed rattlesnake (Crotalus molossus), southwestern cat-eyed snake (Leptodeira maculata), common coral snake (Micrurus distans), eastern coral snake (Micrurus fulvius), and Mexican patchnose snake (Salvadora Mexicana). In the threatened category is the Mexican jumping pit viper (Atropoides nummifer), boa constrictor (Boa constrictor), Mojave rattlesnake (Crotalus intermedius), Mexican pigmy rattlesnake (Crotalus ravus), milksnake (Lampropeltis triangulum), Pacific coast parrot snake (Leptophis diplotropis), and the threatened amphibian Bell's salamander (Isthmura bellii).

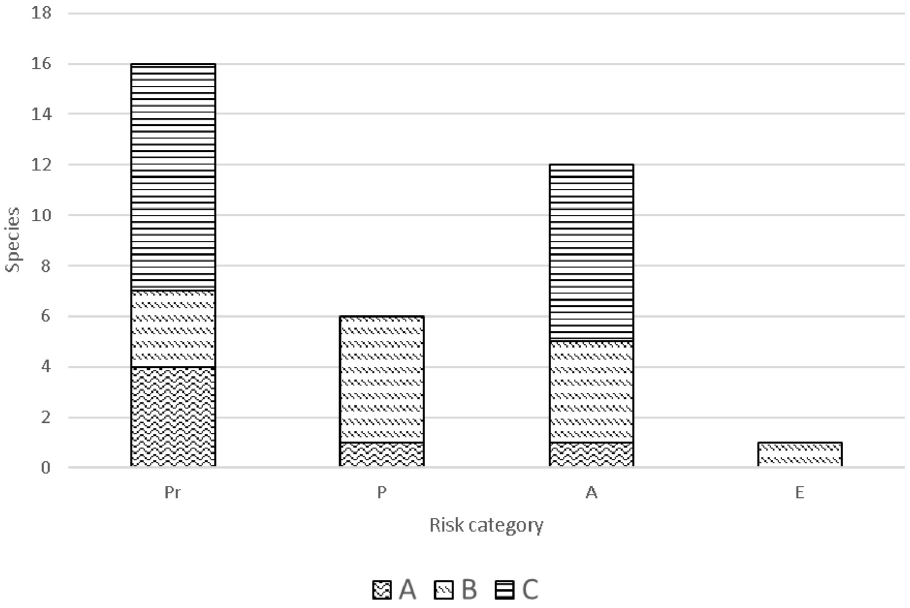

In terms of type of damage inflicted by the protected species, we found that the majority of studies referred to human health (69.9%) and damage to cattle and poultry (44.8%) and crops to a lesser extent (9.1%) (Figure 1). Since attitudes and perceptions can often distort the scale of conflict, leading to extreme measures such as the total eradication of species that represent a threat or the collapse of their population distribution, in particular those species with large home ranges, we consider that this is highly important.

Figure 1 The number of species in any risk category, according to NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010 (SEMARNAT 2010), that caused different types of damage: A) crop damage, B) cattle and C) poultry damage. The risk categories are: E = probably extinct from wild habitat, P = endangered, A = threatened, and Pr = subject to special protection.

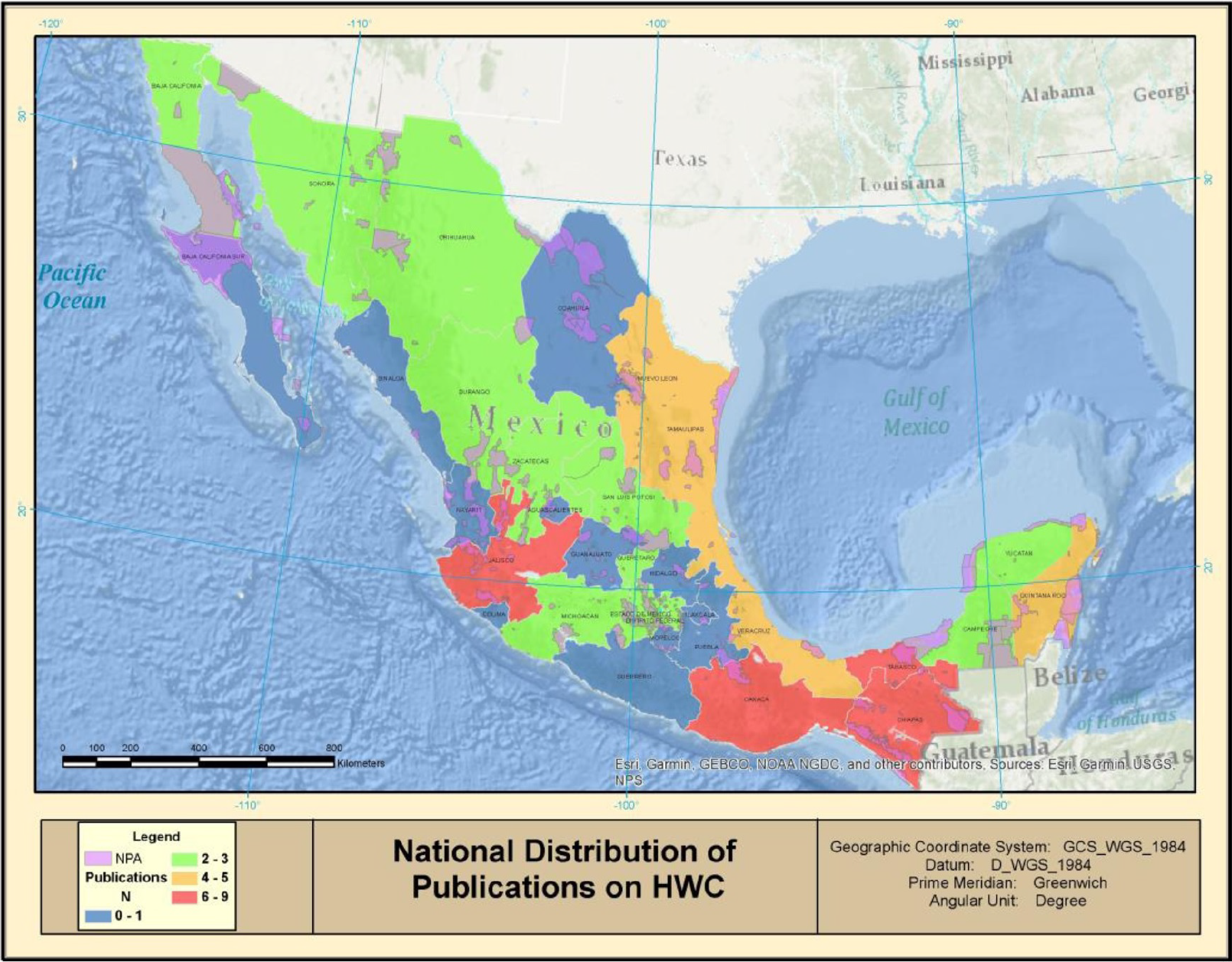

The available studies on HWC were performed in 26 of the 32 federal states in Mexico. The states with the most publications were; Tabasco (9); Chiapas, Jalisco and Oaxaca (each with 8); Quintana Roo and Tamaulipas (5 each); Nuevo León and Veracruz (4 each); and 12 publications that regionally analyzed HWC, in two or more states. States with no publications on HWC included Aguascalientes, Guanajuato, Hidalgo, Puebla, Sinaloa, and Tlaxcala (Figure 2.

Figure 2 Number of studies related to HWC in Mexico in the states and natural protected areas; both federal (SEMARNAT-CONANP 2017) and state (CONABIO 2015).

From the 70 publications reviewed, 43 (61.4%) were undertaken within or in the vicinity of NPA. Twenty federal NPA and seven state NPA were included in studies (Figure 2). It is possible that HWC in protected areas are more visible and studied more, as these areas include important natural resources and ecosystem services that require protection, with human communities living within or around NPA boundaries.

DISCUSSION

Compared with other review articles, including those that analyzed conservation in Mexico and the contribution of terrestrial ecology, which consisted of a total of 839 scientific articles (List et al. 2017), or landscape ecology in Mexico with 472 articles (Arroyo-Rodríguez et al. 2017), and restoration ecology studies in Mexico with a total of 206 articles (López-Barrera et al. 2017), the study of HWC in this country is clearly very limited. The scarce information relating to HWC and particularly the fact that only 43.2% of the documents are scientific articles or book chapters, can perhaps be attributed to the fact that even though such conflicts have existed for a long time and have increased in severity and complexity (Anand and Radhakrishna 2017), they are possibly being analyzed by different disciplines or focusing on a particular issue (such as pest management, accident prevention, public health or cattle raising, among others) and these studies are not being classified specifically as HWC. There are technical issues that further complicate reports and studies of negative events, such as varying conditions (space and time), the lack of standardized methods and techniques to ensure confidence and fidelity in the registered data, as well as the difficulties involved in quantifying damage in a systematic manner over time. It is also possible that the negative effects and the impacts inflicted on those affected and the way they deal with HWC are not reported for fear of being sanctioned by the authorities, or these events may not be considered as sufficiently important to warrant attention, or possibly the losses are accepted, or there is confusion as to which authorities should deal with these problems.

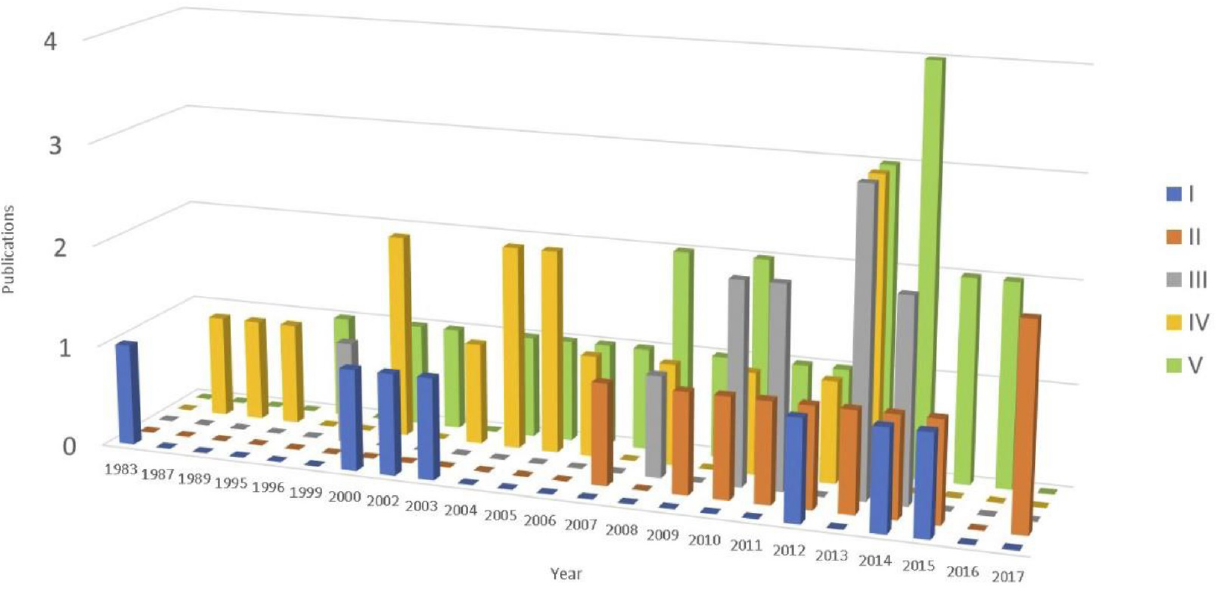

Regarding the topics that have been studied the most regarding HWC, the results are consistent with those reported by Treves et al. (2006), based on experiences in Bolivia, Uganda, and the United States. Their study mentioned that most of the research on HWC concentrates on the identification of the species involved, the seasonality and distribution of the interaction, experimental studies of techniques to mitigate these conflicts, and finally studies on human perception. This is possibly because both the description and the quantification of negative events represent the initial phases in the construction of knowledge regarding HWC (Figure 3, Table 1).

Figure 3 Results in terms of the publications found (absolute values and percentages, n = 70 publications), the categories used, and the number of publications per year. I = identification of the species, II = human perception analyses, III = construction of theoretical frameworks, IV = quantification of negative events, and V = description of negative events.

Table 1 Theme categories and sub-categories of publications on HWC in Mexico.

| 1.-Perception analyses | 2.-Theoretical framework construction |

3.-Quantification of negative events |

4.- Describing negative events |

5.-ID of wildlife species involved in HWC |

| 1.1.-Perception of the conflict |

2.1.-Description of base concepts |

3.1.-Quantification of negative events (economic and in kind, e.g., affected plants, cattle, persons) |

4.1.-Describes spatial and temporal aspects of negative events (real and potential) |

5.1.-ID of wildlife species responsible for damage |

| 1.2.-Perception of species involved in a particular HWC |

2.2.-Describe, propose and analyze types of HWC |

4.2.-Describes behavioral characteristics of harmful species (e.g., movements, foraging, prey seeking and hunting) |

5.2.-Identifies species being harmed |

|

| 1.3.-Reaction and mitigation strategies by those affected |

2.3.-Describe, propose and analyze strategies for mitigating HWC |

Regarding crop damage, the perceptions of damage to crops were represented sporadically in the available literature, this is an issue that we think requires thorough assessment because of the important role it could play in the selection of adequate strategies to protect crops, as well as wildlife. For example, lethal control involves a practice that eliminates species that feed on crops, as well as a means of compensating these losses (Tejeda-Cruz et al. 2014). Of the available publications, only one (Romero-Balderas et al. 2006) analyzed the effect that the landscape has on the presence of wildlife in the vicinity of crops, a theme that could shed useful information for defining habitat management strategies to reduce the damage to both society and wildlife. The high number of HWC studies on jaguars and cougars is probably related to the fact that both are charismatic, endangered species, whose habitat is being rapidly reduced due to land use change. Research on these species has focused on the impact on livestock (Rosas-Rosas et al. 2008,), the distribution of these species and conflicts (Chávez and Zarza 2009, Zarco-González et al. 2013, Hoogesteijn et al. 2016), and the perceptions of these conflicts (Anaya-Zamora et al. 2017).

Damage and death to humans is the most severe manifestation of HWC, as these impacts are more severe and effect human communities, although they are less frequent (Woodroffe et al. 2005). The consequences of attacks on humans go far beyond the unfortunate victim and have repercussions throughout the community (Lamarque et al. 2009). The perceived risks, as well as the fear these incidents provoke, has caused the offending species to be tolerated less by humans (Neto et al. 2011, Arroyo-Quiroz et al. 2017).

Thus, it is important to promote research on how HWC can affect the success of NPA and include such findings in their planning and management. It is also important to generate information regarding the geographical location of potential conflict sites, the perceptions and attitudes of the communities involved (Hill 2004, Arroyo-Quiroz et al. 2017), as well as the tolerance of local population towards the wild species considered to be harmful, whilst analyzing the socio economic attributes that can determine the vulnerability and/or tolerance of people to HWC (Treves et al. 2006, Márquez and Goldstein 2014).

In contrast, we must consider that NPA do not always cover the entire distribution of important species (91% of jaguar distribution falls outside NPA) (Peña-Mondragón et al. 2016). Therefore, research regarding the management of HWC in areas with a distribution of conflictive species, inside and outside NPA, should also be a priority.

Finally, we must take into consideration that the success of different conservation actions inside a NPA may result in an increase in the numbers of different species and therefore HWC may be more frequent, as in the cases related to crocodiles in the Chamela-Cuixmala Biosphere Reserve (Peña-Mondragón et al. 2013) or the peccaries in the Sierra de Huautla Biosphere Reserve (López-Medellín et al. 2017). This could trigger negative attitudes towards conservation policies by local inhabitants who suffer from a growing number of HWC.

CONCLUSIONS

Research in Mexico on HWC is scarce, recent, and mainly promoted by conservation programs from the national authorities to try to deal with HWC. These agencies have the potential to enhance multidisciplinary research and contribute to HWC solutions. Efforts should be integrated into conservation activities that deal with the different interests and priorities of the involved parties. The identification of conflictive species needs to be strengthened, and more effort needs to be made in dealing with the affected parties in order to identify the reasons behind the issues and consequently try to solve them. Such interactions can enhance the vulnerability of the involved species because sometimes it results in lethal strategies to prevent them. The management and solutions for HWC require the involvement of scientific and technical groups and local inhabitants to; work on the environmental education on conflictive species; determine vulnerable areas; establish mechanisms for reporting HWC and define response protocols; and develop new techniques for reducing HWC and their consequences. Finally, it is paramount that all the information is made accessible to all interested parties in environmental management.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)