Introduction

A key concept of current globalization and institutional change discourse is that of Global Value & Production Chains and networks (GV&PC). GV&PC is used to describe a novel feature of the capitalist system composed of geographically-separated units of production with several globally operated coordination mechanisms. There is a quite broad agreement, in that, in the current globalization era, “a single finished product often results from manufacturing and assembly in multiple countries, with each step in the process adding value to the end product.”3 Along with this belief exposed in the media and mainstream academic circles, fragmentation of production as a firm’s strategy is surely the best way to reap the benefits of global production (Lee, Szapiro, & Mao, 2017), reduce costs, and compete in global markets; thus, it is arguably nearly impossible, or certainly inconvenient, for one entity or country to attempt to control the whole production chain. But, is this necessarily the case? The related literature increasingly considers GV&PC as conduits of globalization. For instance, the World Bank says that “GVC (Global Value Chains) integrate the know-how of the leading firms and suppliers of key components along production stages and at multiple offshore locations”, that “countries that embrace them grow faster, import skills and technology, and boost employment”, and that these “provide countries the opportunity to leap-frog their development process.” Not surprisingly, the World Bank argues that to make the majority of this inevitable trend, developing countries must obtain the “right strategy” and, of course, the Bank is ready to provide the necessary assistance to “design and implement effective, solutions-oriented reforms” aimed at opening borders and attracting investment.4 Curiously, the World Bank chooses to praise India and China, two heavily interventionist states, as illustrations for other developing countries. However, these core ideas have mostly gone unchallenged by most governments when it comes to domestic economic governance structures regarding development policies and institutions, notwithstanding the negative consequences, such as income inequality, relegation of local capital, and meager technology transfer by transnational firms and their affiliates. Therefore, our proposal is to challenge the idea that insertion into GV&PC is the most convenient way to engage in globalization and to upgrade the domestic industrial base. We rather agree with the argument that the role of government and industrial policy is crucial (Amsden & Chu, 2003), especially in managing GV&PC, provided there is a clear awareness that attracting Transnational Corporations (TNC) does not automatically deliver sustainable economic growth or spawn technological upgrade. The task is two-fold: first, to show the power of the idea that GV&PC exerts on institutional redesign and, second, to examine the relation between Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) via GV&PC and domestic technology upgrading, and the formation of local capital in value-added activities. Some references to East and Southeast Asian experiences provide illustrative lessons for Mexico and some Latin American economies.

Challenges of globalization to technology development

It is well acknowledged in the literature that globalization is a complex and multidimensional process, involving economic, social, political, and institutional spheres (Attinà, 2001; Beck, 1998; Held, 2000; Held & McGrew, 2003). Hence, it might be best to look at the challenges that globalization poses to technological development through the lens of political economy, especially the role of TNC in international and domestic institutional transformations (Dicken, 1992; Gereffi & Korzeniewicz, 1994; Ohmae, 1997, 2004). Our particular interest in this article is to inquire into the role that TNC play in the process of domestic technology development and the institutional change that entails their inclusion in economic policy design; we also present a critical view of the idea that, as global production is increasingly segmented into networks and modules and coordinated by market forces, developing economies have no choice but to adjust to that process, meaning the opening of specific sectors and providing all kinds of institutional and policy incentives.

Our initial assumption is that when production becomes global and comprehensive, whether as chains or networks,5 it is not faceless, but is coordinated by leading firms with a national base. We understand production as a bargaining process, so transaction costs are at the core of competitive concerns. Therefore, control over the production process is vital; consequently, relying on market mechanisms is only meant for non-critical aspects, not the other way around. Because technology is strategic for competition, key research and development is not outsourced, but remains within the realm of the leading firms. In other words, business competition hinders cooperation in crucial knowledge-based nodes and activities along the production chains/networks.

The above is contrary to the interest of attracting foreign firms, expecting they will share knowledge and technology. In fact, the typical policy incentives of developing countries to attract FDI do not explicitly demand technology transfer for it is considered unreasonable; actually, they tend to abide by strict protection of intellectual property, maintain wage levels relatively low, and labor unions are often deterred in certain sectors and special economic zones and are benevolent in repatriation of revenues. There is also a belief that international cooperation, especially technical cooperation, may contribute to filling the knowledge gap, in addition to the efforts of some developing countries to improve their human capital base. However, despite such an institutional framework and awareness that education would make the difference to take advantage of assumed technology flows, the role of developing economies has been to engage in resource- or factor-based complementarities (natural and human), with little room for the involvement of local suppliers in higher tiers, which are often technology-intensive or highly specialized sectors.

Institutional changes in developing countries target FDI to establish on this segment of production, in the alleged hope that technology would naturally flow or local learning and appropriation would eventually occur; expressed differently, regardless of the segment of the production process that developing countries engage in throughout a GV&PC, it would sooner or later create a demand on the recipients’ economic system for improved competencies, which would induce local firms to fulfill such needs, consequently boosting economic growth. Nevertheless, evidence shows that a positive technological spillover effect occurs only when the country has developed knowledge-absorptive capacities and when there is a public and private commitment to spend on Research & Development (R&D) (Laborda Castillo, Sotelsek Salem, & Guasch, 2011). Moreover, as Suyanto, Salim, & Bloch (2009) suggest, policies that foster national firms’ absorptive capacities through investment in knowledge and human resources should be more important than those providing FDI incentives and access to trade.

Some authors argue that since higher tiers of the production process require adequate human capital for host economies to be attractive, developing countries with low educational levels would scarcely get any chance to link their firms in those phases. Therefore, these countries must pursue extensive education and training programs to at least compete in more advanced second-tier economies and levels (Miyamoto, 2008). However, it is rather difficult to achieve massive education and training in high-tech standards rapidly with market incentives or social encouragement alone. The role of the State is, therefore, essential at the beginning of the process.

For the last 50 years or so, East Asian economies such as Japan, South Korea (hereafter Korea), and Taiwan have achieved a high standard of human resources. Some Southeast Asian countries are at present thriving in catching up to a certain extent, but Latin America continues to lag behind. We think that the chances of catching up lies greatly on the knowledge and scientific base. Table 1 presents a panoramic view of some key features that illustrate the state of such a base and, as can be observed, there are only slight differences between selected Latin American and Southeast Asian countries. With the exception of Singapore and, to some degree, Brazil, the rest reveal low levels of investment (public and private) and of human resources dedicated to research. These regions contrast greatly with the Japanese and Korean cases, which have dedicated significant amounts of resources to develop this aspect of knowledge accumulation, production, and innovation.

Table 1 Knowledge and scientific base

| Country | Gross domestic expenditure on Research and Development (GERD) as a percentage of GDP | ||||||||||

|

Researchers (in Full-time equivalents, FTE

) (Researchers per million inhabitants (FTE)) | |||||||||||

| 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |

| Argentina | 0.42 | 0.45 | 0.46 | 0.47 | 0.59 | 0.56 | 0.57 | 0.64 | 0.62 | 0.59 | N/A |

| 31,868 (814) | 35,040 (886) | 38,681 (968) | 41,523 (1,028) | 42,136 (1,033) | 46,199 (1,121) | 49,029 (1,177) | 50,489 (1,199) | 50,785 (1,194) | 51,665 (1,202) | N/A | |

| Brazil | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.08 | 1.13 | 1.12 | 1.16 | 1.14 | 1.13 | 1.20 | 1.17 | N/A |

| 109,410 (581) | 112,318 (589) | 116,270 (603) | 120,529 (619) | 129,102 (656) | 138,653 (698) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Chile | N/A | N/A | 0.31 | 0.38 | 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.39 | 0.38 | 0.38 |

| N/A | N/A | 5,551 (337) | 5,959 (358) | 4,859 (289) | 5,440 (320) | 6,078 (353) | 6,798 (391) | 5,893 (335) | 7,585 (427) | 8,175 (456) | |

| Colombia | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.24 |

| 5,264 (122) | 6,020 (137) | 6,821 (154) | 7,490 (167) | 7,813 (172) | 8,369 (182) | 7,798 (168) | 6,845 (146) | 5,490 (116) | 5,491 (115) | N/A | |

| Mexico | 0.37 | 0.43 | 0.47 | 0.52 | 0.54 | 0.51 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.54 | 0.55 | N/A |

| 43,922 (400) | 36,264 (326) | 37,930 (335) | 37,639 (327) | 42,973 (368) | 38,497 (325) | 39,826 (331) | 29,094 (238) | 29,921 (242) | N/A | N/A | |

| Indonesia | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.08 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.08 | N/A | N/A |

| N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 21,349 (90) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Malaysia | N/A | 0.61 | N/A | 0.79 | 1.01 | 1.04 | 1.03 | 1.09 | N/A | 1.26 | 1.30 |

| N/A | 9,694 (368) | N/A | 16,344 (599) | 29,608 (1,066) | 41,253 (1,458) | 47,242 (1,458) | 52,052 (1,773) | N/A | 61,351 (2,017) | 69,864 (2,261) | |

| Singapore | 2.16 | 2.13 | 2.34 | 2.62 | 2.16 | 2.02 | 2.15 | 2.01 | 2.01 | 2.20 | N/A |

| 23,789 (5,292) | 25,033 (5,425) | 27,301.4 (5,769) | 27,841 (5,741) | 30,530 (6,149) | 32,031 (6,307) | 33,719 (6,496) | 34,141 (6,442) | 36,025 (6,665) | 36,665 (6,659) | N/A | |

| Thailand | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.23 | N/A | 0.36 | N/A | 0.44 | 0.48 | 0.63 |

| 20,506 (311) | N/A | 21,392 (322) | N/A | 22,000 (330) | N/A | 36,360 (544) | N/A | 53,895 (799) | 65,965 (974) | 59,416 (874) | |

| Japan | 3.18 | 3.28 | 3.34 | 3.34 | 3.23 | 3.14 | 3.25 | 3.21 | 3.32 | 3.40 | 3.28 |

| 680,631 (5,360) | 684,884 (5,387) | 684,311 (5,378) | 656,676 (5,158) | 655,530 (5,148) | 656,032 (5,153) | 656,651 (5,160) | 646,347 (5,084) | 660,489 (5,201) | 682,935 (5,386) | 662,071 (5,231) | |

| Korea | 2.63 | 2.83 | 3.01 | 3.14 | 3.30 | 3.45 | 3.75 | 4.02 | 4.15 | 4.28 | 4.23 |

| 179,812 (3,777) | 199,990 (4,175) | 221,928 (4,604) | 236,137 (4,868) | 244,077 (5,001) | 264,118 (5,380) | 288,901 (5,853) | 315,589 (6,362) | 321,842 (6,457) | 345,463 (6,899) | 356,447 (7,087) | |

Source: UNESCO (2018), Institute for Statistics (UIS.Stat). Retrieved from: http://data.uis.unesco.org

According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO),6 during 2000-2014, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Mexico averaged fewer than 1,000 scientists Per Million Inhabitants (PMI), while Japan, South Korea, and Singapore average well above those figures (Table 1). Singapore, a latecomer, has consistently spent more than 2% Gross Domestic Expenditure on Research and Development (GERD) and has surpassed Japan and Korea with nearly 7,000 researchers PMI in 2014; Thailand and especially Malaysia are demonstrating a notable rise of human capital since mid-2000s. For instance, Malaysia improved from 368 in 2006 to 2,261 researchers PMI in 2015, while Colombia had only 115 researchers PMI in 2014 (a decrease from 182 in 2010), and Chile had fewer than 500 in 2015.

Interestingly, notwithstanding that Latin American countries produce a considerable number of graduates (Graph 1),7 they do not spend as much on R&D (Table 1), which may explain the knowledge- production gap between regions in terms of personnel devoted to research and patent applications (Graph 4). Japan stands out with an average of 3.3% of its GERD between 2000 and 2015, while Korea and Singapore follow close behind with 3% and 2%, respectively. It is striking, however, that Latin American countries spend less than 0.5% of its GERD (except Brazil, which consistently reports spending 1% or more, which is at any rate lower than other Asian countries).

Note: There were insufficient data available on Singapore.

Source: UNESCO (2018), Institute for Statistics (UIS.Stat). Retrieved from: http://data.uis.unesco.org

Graph 1 Graduates from tertiary education, 2000-2015 (Average)

Note: The UIS.Stat does not provide data for Indonesia, Japan, Singapore, and Thailand.

Source: UNESCO (2018), Institute for Statistics (UIS.Stat). Retrieved from: http://data.uis.unesco.org

Graph 2 Percentage of graduates from tertiary education graduating from different fields, 2000-2015 (Average)

Source: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (2018), UNCTADstat. Retrieved from: http://unctadstat.unctad.org/wds/ReportFolders/reportFolders.aspx?sCS_ChosenLang=en

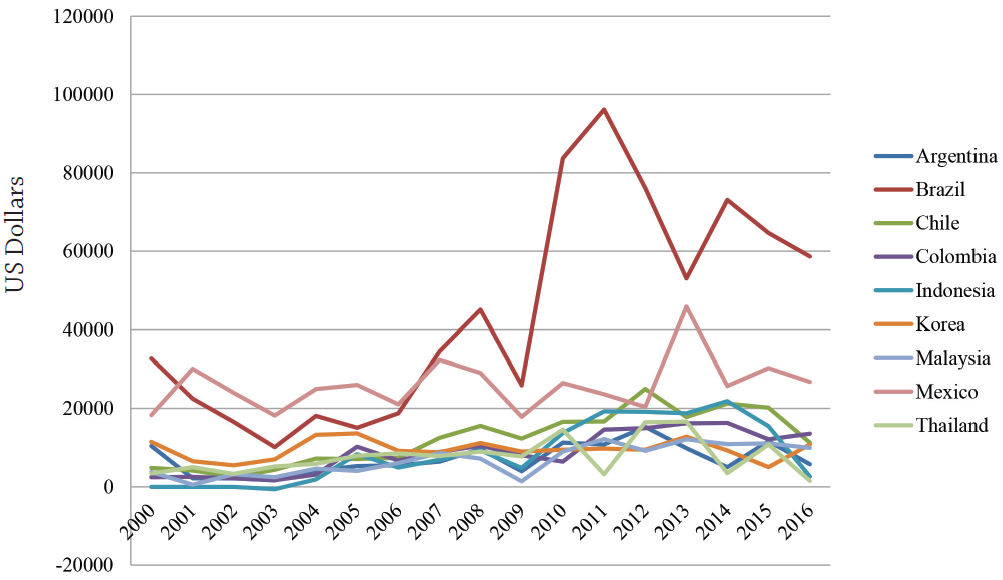

Graph 3 FDI inflow 2000-2016 (US Dollars at current prices in millions)

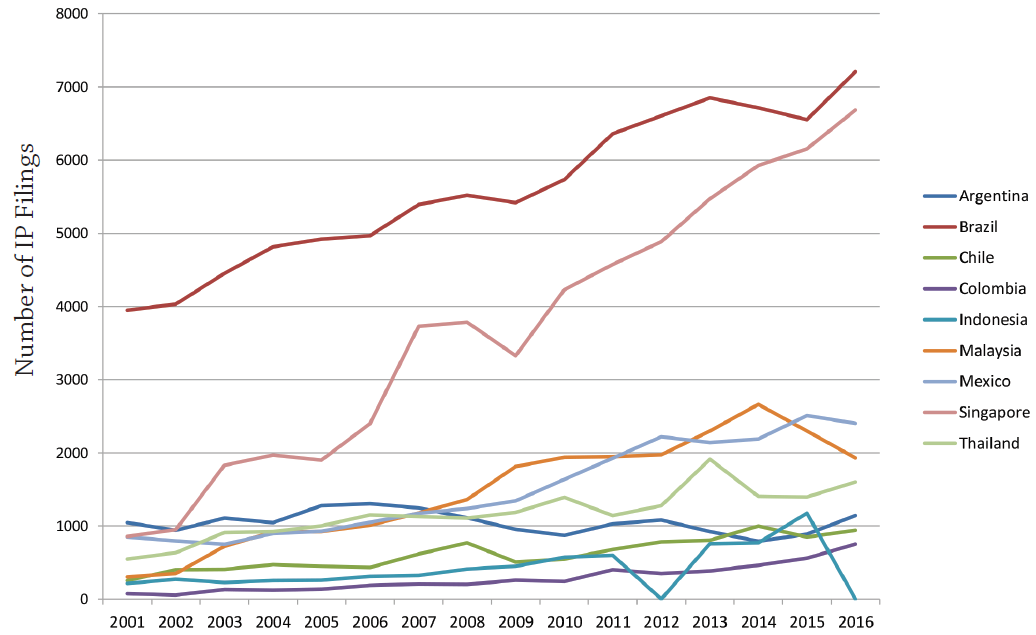

Note: IP filings are defined as the sum of resident and foreign filings.

Source: World Intellectual Property Organization (2018), Statistical Country Profiles. Retrieved from: http://www.WIPO.int/ipstats/en/statistics/country_profile/

Graph 4 IP filings, 2001-2016

However, it is not only the fact that Latin America dedicates few resources to R&D, but that of the academic areas where human resources are formed. It is noteworthy that, in the very foundation of the capacity building of the scientific critical mass, several Latin American countries produce more social scientists, journalists, information specialists, business administrators, and lawyers than engineers, both manufacturing and construction, natural scientists, and mathematicians than their Asian counterparts (Graph 2).

Against this backdrop, we consider it plausible that achievements regarding the knowledge and scientific base reflect on the learning capacity of local firms, therefore on knowledge and patent production, providing the autonomy to develop their own technology and innovation networks and eventually emancipating them from foreign production networks (Lee, Szapiro, & Mao, 2017). In other words, we assume that technological dependency may be related with the institutional setting and with development policies toward TNC, which include human resources formation.

Therefore, we raise the question concerning whether regional development schemes that establish special economic zones or industrial clusters are adequate responses to facilitate technology transfer from TNC and to support long-term growth, equity, and sustainability. That is, are the expectations in terms of TNC realistic for technology transfer if the policy goal limits itself to capturing nodes of global production networks?

In response to these queries, we propose to reset traditional mainstream expectations toward TNC. It is not our intention to deny the importance of GV&PC and the potential contribution of TNC and their production networks for developing economies: they certainly provide jobs. However, evidence hardly shows that transnational capital alone brings about sustained economic growth, or that leading foreign firms automatically integrate local firms unless they are already within a specialized cluster, or stimulates indigenous technological upgrading (Dussel, 2009; Romo, 2005). In the last 15 years or so, both Latin American and Southeast Asian economies have been large recipients of FDI, especially Brazil and Mexico, which attracted more FDI than Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, and even Korea (Graph 3).

However, even though FDI in Latin America is relatively high among developing economies and represents larger percentages in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) than other Southeast Asian countries (except Singapore), economic growth has been modest at best, and patent applications as a proxy for industrial technology advancement are negligible. For instance, according to the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), in 2015 and 2016, Korean patent applications alone were 12 times higher than those solicited by Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Mexico together; for Korea, the majority of applications were requested by Korean residents (Graph 6).8

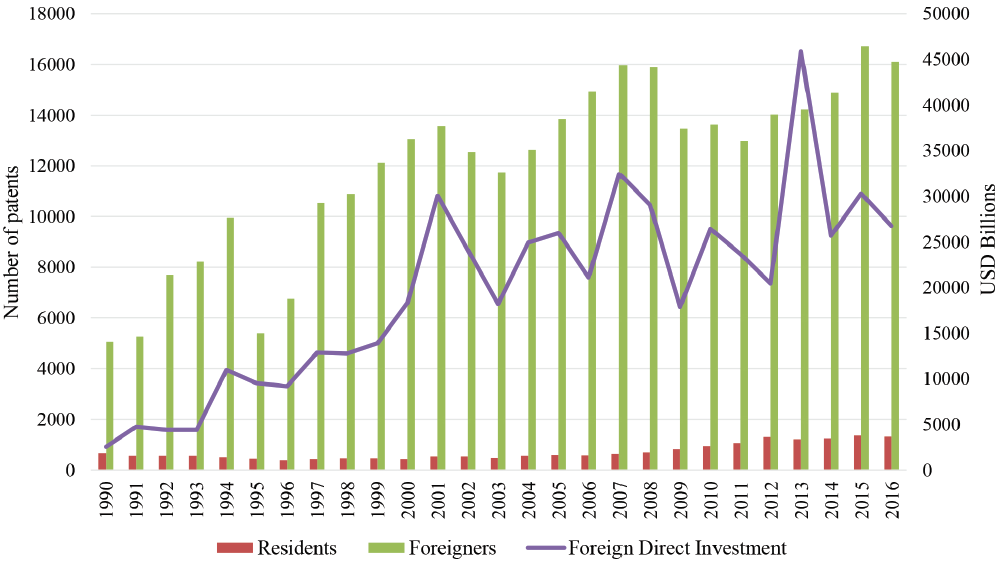

Note: the purpose of setting 1990 as the initial year is to show the change of rules after NAFTA and the extent it contributed to the increase of FDI and patents in Mexico, but not to patent applications by Mexican residents.

Sources: The World Bank (2018a), Foreign Direct Investment. Retrieved from: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/bx.klt.dinv.cd.wd; United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (2018), UNCTADstat. Retrieved from: http://unctadstat.unctad.org/wds/ReportFolders/reportFolders.aspx?sCS_ChosenLang=en; World Intellectual Property Organization (2018), Statistical Country Profiles. Retrieved from: http://www.WIPO.int/ipstats/en/statistics/country_profile/profile.jsp?code=MX; Instituto Mexicano de Propiedad Industrial (2016).

Graph 5 Patent applications by Mexicans (residents), foreigners, and FDI in Mexico (1990-2016)

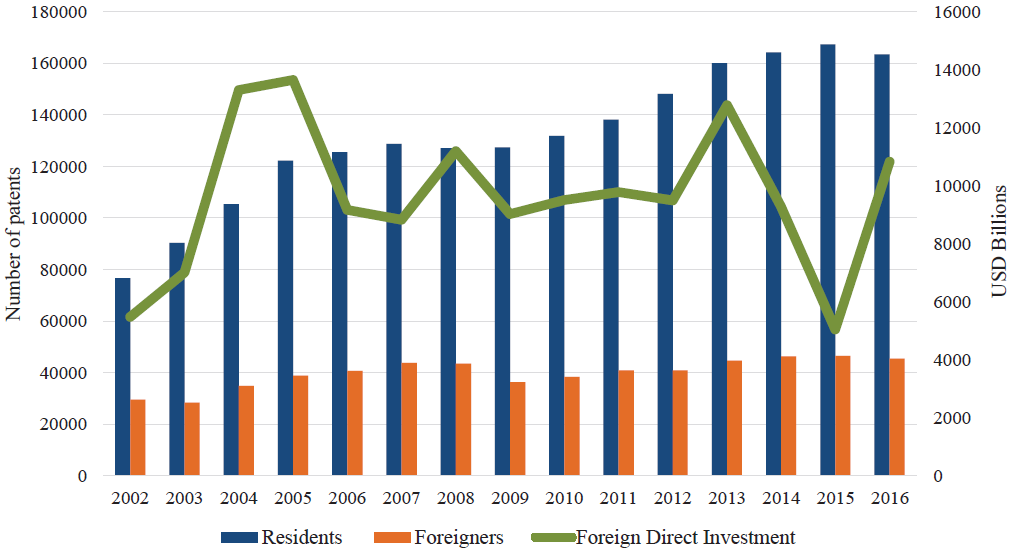

Sources: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (2018), UNCTADstat. Retrieved from: http://unctadstat.unctad.org/wds/ReportFolders/reportFolders.aspx?sCS_ChosenLang=en; World Intellectual Property Organization (2018), Statistical Country Profiles. Retrieved from: http://www.WIPO.int/ipstats/en/statistics/country_profile/profile.jsp?code=KR

Graph 6 Patent applications by Koreans (residents), foreigners, and FDI in Korea (2002-2016)

Actually, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Singapore apply for nearly the same number of patents than the five Latin American countries previously mentioned taken together. We decided not to include Korea or Japan in Graph 4, because the remainder of our sample would be barely distinguishable at the bottom of the chart.

We think that one way to assess the impact of FDI on domestic capabilities for technology accumulation and development is to look at patent applications made by residents. As an illustration, consider the particular case of Mexico regarding the correlation between FDI and patent applications solicited by residents in the Mexican Institute for Intellectual Property. As Graph 5 depicts, despite the increase in FDI after the North America Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA, 1994), the gap between foreign and resident patent applications did not narrow, but actually widened. This can be read in two ways: one, that this is due to the overwhelming protection of knowledge on behalf of foreign firms (granted by NAFTA and the associated commitments to trips),9 and the other is the poor knowledge and scientific base due to weak education, and science and technology policies in Mexico.

The Mexican case presents a sharp contrast with South Korea. With relatively low inflows of FDI, Korean residents are capable of performing multiple technological advancements and applying for several thousand patents, by far overtaking foreign applicants (Graph 6). To us, this reveals that large amounts of FDI inflows are not necessary a condition for technological advancement for domestic firms and, consequently, their enhancement for participating in GV&PC; in fact, it could be the opposite.

By observing the Korean case, Lee and his colleagues (2017, p. 3) argue that

[...] while more integration to the GVC is desirable at the initial stage, upgrading at a later stage requires that the latecomer firms and industries exert effort to seek a temporary separation from the existing foreign-dominated GVC, although these firms might have to seek for more openings to integrate once more in the GVC after upgrading.

Therefore, Korea learned from foreign firms by engaging with their international production networks (Amsden & Kim, 1985; Castley, 1997, 1998; Kim, 1997); however, subsequently, they established their own local value chains and have been keen to produce their own knowledge base to leverage “a bigger piece of the pie from the global profit” (Lee, Szapiro, & Mao, 2017, p. 3). Recent research shows that the transformation from dependent or subcontracting firms into independent firms is surely an individual challenge in terms of cultivating firm-specific knowledge (Lee, Song, & Kwak, 2015), but also a policy challenge in terms of creating adequate institutional conditions (Lee, Szapiro, & Mao, 2017).

That said, we presume that a major reason for the difference in countries’ education, foreign investment, and patent-application profiles is related to the industrial development strategy and institutional setting. These two aspects shape production-specialization patterns and stipulate the role of foreign firms. In the case of some Latin American and Southeast Asian countries, the function of foreign investment is consistent with a strategy based on an inexpensive and low-skilled labor force and the exploitation of raw materials (Gallagher & Chudnovsky, 2009; UN-ECLAC, 2014). Therefore, in order to move away from the drawbacks of such an economic structure -such as the middle-income trap- and avoid hindrances set by unrestricted foreign investment inflows, a new development strategy and institutional setting must be pursued by governments and economic actors.

If developmental-state success stories can teach us anything, it is that economic development is a domestic task for which an institutional framework must be established with the explicit purpose of extracting benefits from global forces, other than only creating jobs. One key feature of the model in its early configuration is the establishment of rules that enable the government to channel or influence the allocation of financial resources (foreign or domestic) to certain sectors and economic activities considered strategic by the economic plan. Such an attribute is accompanied by an industrial policy that commands the allocation of other policy incentives to the targeted sectors, although this later evolved into a more functional role (non-sector specific incentives); commercial, financial, monetary, fiscal, procurement, and educational policies are all intertwined around the industrial policy with the objective of fostering national firms to grow and to achieve scale economies, and also to produce the majority of components and capital goods domestically. The role of TNC in this model is functional, rather than one that must be predominant for economic growth.

In the early stages of economic and industrial development, East Asian countries such as Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, China, and Singapore linked their foreign-investment regime with their industrial policies pursuing their developmental goals -chiefly, economic growth- by nurturing domestic capital and technological development (Amsden, 1989; Dent, 2003; Wade, 1990, pp. 148-157). The contrasting development stories of East Asian and Latin American countries in terms of their relationships with TNC demonstrate that overreliance on foreign firms may inhibit domestic industrial and technological upgrading and social welfare due to their narrow focus on seizing benefits in efficiency, resources, or market access from the host economy (Gallagher & Chudnovsky, 2009).

Furthermore, TNC do not eliminate economic and social inequality when they are invited to exploit the benefits of special industrial or technological clusters and agglomeration economies, which are not necessarily linked to local or regional networks. Thus, instead of TNC and GV&PC contributing to reducing income gaps, it appears that they widen them by creating “two-track” (or two-speed) economies, as in Mexico (Bolio et al., 2014; Dussel, 2009). Therefore, the challenge for the State is to articulate clusters institutionally with regulation aimed at linking local suppliers to production networks or chains. Additionally, if local suppliers in high tiers are unavailable at some point, they should be fostered as private, public, or mixed projects, as Korea and Taiwan did in the 1960s and 1970s (Castley, 1998). The East Asian developmental experience has shown that the development of local value chains and knowledge around GVC is possible (Lee et al., 2017), but it is accompanied by a mounting effort from private and public agents to upgrade human and technological capabilities, along with a sense of economic nationalism to keep the pace (López Aymes, 2009). East Asia shows there is a way to promote indigenous technological development, although the context in which these cases could thrive cannot be overlooked, nor the tensions between the TNCs interests versus States’ autonomy in the process of institutional development.

GV&PC and institutions for technological upgrading

What is the role of economic and political institutions in linking global production to the national interest of upgrading the knowledge and scientific base? Once our expectations of the role of TNC in technological upgrading have been reconsidered in the light of their contribution to domestic knowledge and a scientific base, it follows that one must revisit the concepts of global production and value networks as modes of international-production governance. GV&PC are often conceived as concrete manifestations of current international capitalism, characterized by an extended use of information and communications technologies, efficient transportation means, and relatively unrestricted movement of goods and services. Whether global chains or networks (see Footnote 3), both governance forms organize the several segments of production in sophisticated ways. They interweave the geographic dispersion of extraction, production, and distribution by means of a combination of market, contract, or property relations in which one or more segments of the process are performed outside the national territory of the leading firm. GV&PC link global and local economies indeed; paradoxically, they do so by segmenting technology and production. As organizational forms, leading firms seek to employ chains or networks especially to control the value-added segments of the productive process (Gibbon, Bair, & Ponte, 2008). Given these characteristics, we ask whether GV&PC in fact contribute to the domestic technological upgrading of developing countries by forming and integrating local firms in upstream and downstream linkages, which theoretically lead to socioeconomic improvement (i.e., living standards and environment).

It is noteworthy to indicate the differences between both forms, particularly those related with control, governance, and decision-making mechanisms. On the one hand, the so-called “chains” entail holding-like centralized and relatively linear and hierarchical governance, often based on property relationships in each “link”, including their affiliates and some group suppliers. The chain-like organization refers to the control and coordination of exchanges in the majority of production stages and only seeks standard intermediate goods and commodities in the open market. On the other hand, although there are several types of networks (Carney, 2005; Gereffi, Humphrey, & Sturgeon, 2005), a common feature is the flexibility afforded by preferring subcontracting instead of ownership for organizing and controlling production.

Some governments in developing countries have established differentiated institutional configurations with all sorts of incentives -such as special economic zones and clusters with specialized physical infrastructures- in certain provinces or districts, hoping to host some of those segments, to create micro economic systems around them so local producers could take part in the spillovers that nurture regional development (Johansson, 1994).10 This makes sense from a purely managerial and business standpoint, but from a political economy perspective, it is rather problematic. This is so because fragmentation and specialization may hamper the comprehensive management of the production process and knowledge, thus hindering prospects of adding sources of wealth, innovation, and control over industrial integration.

Empirical studies show that local firms can be upstream and downstream suppliers in global networks providing that they exhibit reliable capabilities and compatible technologies (Carluccio & Fally, 2010). Other authors show that high-tech segments of the production process would go where human capital is well developed (Miyamoto, 2009). So, there is room for taking advantage of GV&PC, but also for institutional incentives and support to place domestic companies in a better position in the long term. However, an industrial policy designed solely to engage segments of production chains often fails to avoid the specialization trap in generic and labor-intensive segments of production, such as manufacturing and assembling, or even in a single technology-intensive component (e.g., semiconductors). This self-imposed limitation -reinforced by setting up special economic zones and clusters- could ultimately lead to overall dependency on and exposure to severe price fluctuations if it is not coupled with a comprehensive industrial policy that articulates regions and sectors more horizontally, and aims to master several stages and technologies.

Alternatively, an integral industrial policy may be established to avoid the negative impact of segmentation GV&PC by articulating a comprehensive institutional approach covering education, financial, and trade policies. In East Asia, such an approach aimed at enabling the potential participation of local firms (startups or firms created with that purpose) in larger segments of the production process. Industrial policies of Japan, Korea, and Taiwan fostered technological and managerial learning capabilities, but also selected segments of the production process and various economic sectors and industries with strong and wide positive externalities.

Another issue regarding GV&PC is the neoliberal myth that domestic political economies cannot (and should not) seek to extract social commitments from foreign and local firms aside from that of so-called “corporate responsibility”. By reviewing the organizational characteristics of global networks, one may find that these are not necessarily faceless governance structures or loosely attached units of production and services, but that they are coordinated by hierarchies and can be quite closed and nationally oriented (Debaere, Lee, & Paik, 2010; López Aymes & Salas-Porras, 2012). Some studies on Asian production networks cast doubts on the existence of such a thing as a pure global network (Borrus, Ernst, & Haggard, 2000; Carney, 2008); evidence points to the conclusion that the process of production internationalization continues to operate as regular production chains, often involving hierarchies, ownership relationships to discipline affiliates and subsidiaries, or some sort of relational contracting based on ethnic and national traits. Therefore, countries do not deal with invisible forces, but with firms and corporate executives who can be approached to request significant technological contribution. China’s firms and government have done an outstanding job in leveraging concessions as part of their industrial catch-up strategy (Mathews, 2017).

Furthermore, firms in technology-intensive sectors need to be associated with governance structures that provide certainty for their long-term investment and to avoid risk. For that reason, central or leading firms do coordinate the process (either in chain or network-style segments) and they set not only technical specifications and standards, but also strict timetables and goals from the beginning to the end; leading firms leave as little as possible to the uncertainties of the market, narrowing information gaps and reducing transaction costs by dealing with their long-established supply networks, which expand globally alongside their main clients. Whether in Mexico, Vietnam or India, the Korean conglomerates, such as Samsung Electronics, LG, Hyundai Motors, and Kia Motors, are typical examples of such a business approach. Therefore, dealing with globalization forces may not intend to interact with impersonal networks, but with cliques that entertain strategies, discourses, and financial means that are mobilized accordingly. This has been the case of East Asian TNC for quite a while (Borrus et al., 2000).

A political-economy perspective of institutional development within the context of globalization may be helpful to address the tension between accommodating national policies and market regulation to global networks’ needs and interests or, instead, to target the national interest by pursuing economic wealth with some degree of autonomy. In order to achieve the former, developing countries must assess their comparative and competitive advantages, whether present or potential. Hence, comparative and competitive advantages can be conceived as dynamic features of international development, for which East Asian countries offer illustrative case studies (Chang, 1994; Johnson, 1982; Wade, 1990). However, given the domination and monopolization of knowledge of the TNC,11 technological upgrade is neither a natural nor an automatic consequence of allowing segments of a production process to be established in any given country or special economic zone.

Thus, we ask again, what is the role of economic and political institutions in linking global production to the national interest and technology upgrade? Is the debate on institutions that govern the market, such as property regimes, still relevant? At this point, we cannot evade the question that if international relations concern interactions between States, as well as between transnational non-State actors (i.e. capital and other major political agents), does it mean that the debate on globalization and the capital organized in GV&PC as opposed to industrial policy and State autonomy is meaningless?

We think the debate is not meaningless, especially in the light of mounting evidence that wealth inequalities have actually widened and that the market alone or TNC leeway have not provided answers to the problem. But the question of what an industrial policy for globalization should (institutionally) look like remains. What should policy goals and instruments be, and how should we deal with global networks as described? Industrial policy is an institutional figure not only for establishing constraints and commitments to global networks and their leading firms, which will naturally fill the gap of suppliers with their own trusted partners, but also for designing public policies that nurture domestic suppliers, and eventually, create indigenous leading firms.

The extent to which GV&PC rely on local suppliers and local support industries may depend on firm-specific cases, sectors, and the strategic industrial policy, as well as on the science and technology policies pursued by host countries. For example, as we mentioned earlier, Korea and Japan were able to direct capitalism institutionally in part by curbing foreign companies with a strong grip on foreign-investment regimes (Dent, 2003; López Aymes, 2015), and also by the synergies that industrial policies created on the firms’ abilities to take advantage of foreign companies’ operations at home (Castley, 1997). In contrast, current foreign-investment policies in Mexico do not place any property-requirement or joint-venture conditionality, except for a few sectors. As a result, leading companies of global networks are not compelled to integrate domestic firms in order for their traditional suppliers to remain in the first and second tiers, leaving local companies to perform a marginal role in generic and low-end components. Kia Motors in Nuevo Leon, Mexico, is an illustrative example of how a local and national governments fail to surpass the limited achievement of job creation, instead of aiming to fully engage indigenous auto-part firms. This means that any possible knowledge and technological upgrades from potential suppliers have to be acquired at the domestic firms’ own risk, which renders any aspiration for higher status and revenues quite challenging.

In the case of some Latin American and Southeast Asian countries, the function of foreign investment is consistent with a strategy based on an inexpensive and low-skilled labor force and the exploitation of raw materials

Who has the edge in the fragmentation of production and technology?

Global production networks in the emerging economies are copiously found in East and Southeast Asia, whereas Latin America’s participation in these networks has been limited to date to a few countries, mainly Mexico and Brazil (CEPAL, 2013, p. 52). The influence of Japanese, Korean, and Chinese networks is apparent in the integration of Asian production (Borrus et al., 2000). These formations are constructed in order to build competitive advantage at the level of the firm, the country, and the region, meaning that networks tend to be highly stratified and are designed to confront competitive pressures from other firms. For instance, Dieter Ernst (1994) considers Japanese firms as “carriers of regionalization”, shaping Asia’s patterns of specialization (particularly in electronics) and structural changes as the region becomes an extension of Japan’s export base. More recently, Korean business groups have developed their own intra-firm and intra-group networks throughout Asia in a similar fashion as their Japanese counterparts.

However, as Grossman and Helpman (1992) point out, innovation is a deliberate outgrowth of investments in industrial research by forward-looking, profit-seeking agents, so when networks introduce greater knowledge-content segments, inter-firm cooperation and knowledge diffusion may become more difficult (Lee & Yoon, 2010). There is fairly wide-spread awareness that technology development has profound implications for the survival of firms: for this reason, knowledge acquisition and dissemination is so important. In this process, although Japanese and Korean leading firms have gradually opened their procurement from non-Japanese or non-Korean affiliates, control over core technologies and components has been a constant strategic concern for these Asian business networks, even as they become global (Ernst, 1994, pp. 10-12; López Aymes & Salas-Porras, 2012; McNamara, 2009).

Firms’ strategic choices: production networks and ownership as means to protect knowledge

Literature on business networks and its relevance for production and innovation is already vast. The shapes and characteristics of GV&PC by industry and nationality have been revised by scholars from several fields, from organization and management to political economy and geography (Carney, Gedajlovic, & Yang, 2009; Ernst, 2009; Gereffi et al., 2005; Hemmert & Jackson, 2016). The cases studied indicate that networks are established to tap local advantages in human resources and infrastructure, markets, and institutions, but also, that technological know-how “remains to a substantial degree national and local” (Borrus et al., 2000, p. 11).

Therefore, although knowledge networks have proliferated geographically in hubs and players have diversified, core knowledge and technologies are still very much dominated by TNC from the North, mainly the United States, Europe, and Japan (Ernst, 2009).12 Thus, the challenge that many developing countries are facing is how to develop absorptive capacities through learning, increasing R&D, and pursuing technology diversification in attempts to climb the technology ladder (Lee et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2017). China and Korea, and to some extent Singapore and Malaysia, have been somewhat successful in catching up, but it has been a policy-oriented rather than a market-driven process (Ernst, 2009, 2011; He, 2015; Lee, 2016; Sun, Von Zedtwitz, & Simon, 2007; Zhou & Xin, 2003).

Whether or not technology leadership is tantamount to success in global competition at country and firm levels, it is certainly a major concern for both, because lagging substantially behind may have lasting dependency implications. Hence, the commitment to prioritize technology for national development will make the difference between joining global networks at higher or lower stages of the production process. Of course, every country aspires for their firms to participate in technology-intensive and high-value segments, even if this is accomplished by acquiring specific knowledge and capital goods from abroad. However, stopping at such a narrow goal bears the risk of breeding only limited and temporary advantages to overall national development and economic growth, as it misses the one key developmental goal: to develop an integral knowledge of the production process. This risk is of great magnitude due to the inherent fragmentation of GV&PC and the dynamic nature of FDI flows.

Related to the dangers of narrow specialization without social mastery of the complete process we find the issue of limited technology transfer, acquisition, and cooperation. In addition to the institutional protection bestowed by patent regimes, GV&PC also comprise a great organizational innovation to keep knowledge fragmented and secure for leading TNC. Dennis McNamara (2009) raises a relevant question about the manner in which business interests thwart cooperation in innovation and technology transfer, notwithstanding the fact that many components and technologies may not be readily available within national borders or within the organizational boundaries of firms and R&D centers. This is perhaps a matter of trust and opportunism (Nooteboom, 1996), a characteristic concern with respect to intellectual property protection.

Therefore, it is perhaps convenient to reconsider to what extent a country should depend on GV&PC as the most convenient way to engage with global production, access technology, and foster economic growth. Technology transfer occurs within networks in the form of standards and licenses, but mostly in certain stages (such as in OEM subcontracting) and in rather closed levels of the organization. Against this backdrop, some Southeast Asian countries appear to thrive in catching up and the region also reveals a multiplicity of cases of industrial and regional developmentalism, implying the involvement of governments in productive processes following typical economic nationalism goals: to develop their own industrial base.

Institutional development in Southeast Asia: economic policies and regional integration through GV&PC

Southeast Asia is clearly a strategic zone in several ways, but mainly as a source of natural and human resources, and as a mega-intersection among Asia, America, and Europe. However, people and governments in the region have not always being able to establish their insertion into capitalism on their own terms, especially regarding their property of natural resources and, more recently, the control of manufacturing, transport, and financial services (Dixon, 1991). Despite constant foreign involvement in domestic economic affairs as new developmentalist elites in the region have consolidated, economic nationalism has been aimed toward industrialization, which meant developing and controlling economic sectors on their own. The development experiences of Korea and Taiwan implied a realistic possibility to create new comparative advantages and to overcome the old colonial linkages without abandoning capitalism, thus presenting an encouraging pathway to Southeast Asian governments.

In the same fashion of early developmental countries, the industrialization strategy in Southeast Asia was initially promoted through Import Substitution (ISI). Although protectionist ISI policies were common in the early stages of industrialization during the 1960s and 1970s, export promotion strategies were also implemented, but with some variation in timing throughout the region. For instance, Singapore stands out by having dropped ISI and focusing on exports and international financial services, while Thailand and other countries prolonged ISI a bit further.

At the beginning of the modernization (post-war) era, protectionism, inadequate physical infrastructure, the scarcity of qualified human resources, and weak legal systems (including property rights protection) played against Southeast Asian governments’ efforts to attract foreign firms. Industrialization thus advanced slowly, along piecemeal reforms on investment and property regimes attempting to balance nationalistic concerns with technology acquisition and economic growth. Singapore is a singular case, which began to shift toward an open market economy nearly at the time of the beginning of independence in 1965; Malaysia, Thailand, and The Philippines followed nearly two decades later; Indonesia, Vietnam, and Burma were next (Dent, 2003; Dick, 2005; Ofreneo, 2008). After several reforms and economic cooperation through the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN), intra-regional trade grew significantly, especially intra-firm and intra-industry trade of semi-processed goods, which had the lowest tariffs (World Trade Organization, 2011).

In addition to the operations of Japanese and Korean production networks, an additional factor in the Southeast Asia integration process and its linkages to the wider regional economy may be observed in the growing importance of China, especially since it initiated its modernization in late 1970s and early 1980s. Chinese business networks quickly joined the process of regional economic integration, which placed smaller Southeast Asian countries at a competitive disadvantage if they remained economically and politically fragmented (Wong & Chan, 2002).13

The importance of the growing regional integration of Southeast Asia has been recognized by its neighbor countries and the grouping has taken advantage of the rules and external rivalries by collectively extracting commitments (Kim, 2009; Umbach, 2000). Of course, there is competition for attracting foreign capital, which may at times weaken collective action (Pangestu, 1990), but in general intra-regional cooperation has hung on to a fairly unified position (Tay, 2014). This stability has aided the region to become a nerve center in the regional production system, mainly due to the variety of resources and levels of development, permitting the establishment of several stages of production in the area. These characteristics have also been boosted by the multiplication of inter-regional trade and investment agreements to facilitate participation in production chains and networks (Kawai & Wignaraja, 2013).

The inclusion of Southeast Asia in international capitalism has gone through several phases; from extractive activities to productive FDI, where Japan has always been a protagonist (Beeson, 2001; Bernard & Ravenhill, 1995; Cumings, 1984; Ernst, 1994; Lim, 2008). After the 1985 Plaza Accord, Japanese firms were unquestionably the main source of capital, while attempting to accommodate their own networks after the shock (Kimura, 2006; Tachiki, 2005). By that time, the Southeast Asia industrial base was already ripe to receive productive capital, at least as assembling centers and export platforms. Previous industrial policies and human-capital formation enabled such role. Industrial policies also resulted in the establishment of financial and business centers that were gradually articulated by an ample land, sea, and airways interconnection system, built and upgraded decades before during the developmental catch-up era (Suehiro, 2007).

The majority of industrial development in Southeast Asia took place mainly in urban areas, thus creating the so-called “regional urban corridors” or “city networks” (Dick, 2005), the majority of which were to some extent linked to Singapore. Although Singapore has been considered the most important regional hub for international and regional business networks, each Southeast Asia government has attempted to develop market-friendly institutional frameworks and to cultivate their own connections and infrastructure in order to attract productive activities (Ariff, 2008; Techakanont, 2011). This has been done by assuming that comparative and competitive advantages are dynamic, making the best of, but not limited to, the geographic attributes and factors of production endowments.

The majority of the nodes of the regional production network are situated chiefly in capital cities such as Kuala Lumpur, Bangkok, or Jakarta, and in their metropolitan zones, mainly for exports. There are some other sub-regional production networks, often promoted by local governments and featuring cross-border transactions driven by foreign direct investment from Japan and based on a multi-tier division of labor (Peng, 2000, 2002). The concentration of economic activities and localization of national and foreign companies in major cities and extended metropolitan areas respond to the logic of scale economies and agglomeration: exploit competitive advantages such as proximity to large labor-and-goods markets, common suppliers, and resources, knowledge sharing, special legal frameworks, and physical infrastructure, among other assets (Kagami & Tsuji, 2003).

In theory, these conditions should become incentives to attract financial capital and human resources (both foreign and national), thus reproducing and strengthening local advantages. Despite such advantages, however, a drawback of regional urban corridors is that wealth production and accumulation has not been replicated in areas distant from capital cities. This shows that wealth and technology diffusion are not automatic outcomes of engaging GV&PC, notwithstanding available information and communication technologies. This is apparently so because the set of institutional incentives -special economic zones, export processing zones, industrial clusters, and the like- and the well-established infrastructure that connects the economic system in Southeast Asia, have been built for export activities. Consequently, a local economy that is not engaged with global trade could be “further away” from its own capital city than two physically distant capital cities in the region (Dick, 2005).

As in several developing countries seeking to attract FDI, Southeast Asian economies have followed the strategy to establish differentiated legal frameworks in certain territories to engage global networks, although with different degrees of success throughout the region (Dixon, 1991, Chapter 5). Malaysia has been quite successful in establishing special economic areas, such as the famous Penang industrial zone for electronics;14 throughout the 2000s, five additional “development corridors”15 and regional cities were launched, covering most flanks of the territory, each with a particular program for sector development and an authority in charge of their implementation. In Vietnam, the government designed nine “economic zones” -also labeled as “key economic zones”- within the context of the “renovation” (doi moi) program that consists of directed modernization and controlled opening. The least effective country in the creation of special economic zones has been Thailand, mainly because it found it difficult to accommodate old ISI policies with the export promotion goal that supposes the cluster policy (Dixon, 1991).

Despite advancement on other areas, Southeast Asia has not escaped from the fragmented nature of international capitalism discussed previously, which limits the economic integration of other sub-regions; thus, it does not fully benefit from the spillovers of global production and value chains. With the apparent exception of Malaysia and Singapore, this organizational fragmentation explains to a certain degree the wide income, infrastructure, and human-resources unevenness within domestic regional economies. Thailand presents an extreme case of the industrial-segmentation and economic-polarization problem (Mudambi & Navarra, 2002; Sajarattanochote & Poon, 2009; Techakanont, 2011), which is ostensible in the automotive and electronics belt throughout the so-called Great Bangkok-Chachoengsao-Chonburi-Rayong corridor against the more neglected Northern region of Thailand.

As we know, technical formation and infrastructure are key elements of integration to production chains and networks; therefore, these capabilities should also be expanded to and developed in other minor cities, territories, or provinces within Southeast Asian States. Notwithstanding the latter, this has yet to be accomplished. Therefore, the challenge of governments regarding public policies and institutional building is to improve the quality of education and the physical infrastructure, but to maintain a developmentalist view in order to reduce the gaps between the marginalized locations produced by global networks. The role of industrial policy is to create and upgrade local producers by supporting startup programs, to nurture and protect infant industry, and to support local firms for building and upgrading their capacities so they can join global networks, learning how to manage and govern them in order to eventually build their own (Lee et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2017). Korea, China, and Singapore are examples of such a stage-by-stage integration and turnaround propelled by market forces but guided by policy goals.

Chains and agglomerations

Production agglomerations have existed in Southeast Asia for quite a long time (Nguyen, 2009), although they were focused on local consumption, with few linkages to the rest of the national economy, and certainly none to international flows. Currently, the challenge has been to connect these poles of industrial wealth to a national scale and to join larger trade circuits. There are several origins and forms of agglomeration, but the geographic component comprises a common base of the definition. In terms of origin, these can be spontaneous (market-driven) (Enright, 2003; Yeung, 2009) or deliberately created to foster local and national development (Balderrama & Chávez, 2011; Kagami & Tsuji, 2003). In terms of forms, it is paradoxical that in the current global economy, the geographic factor in localization remains relevant despite the advance in transport and communication technologies (Baldwin, 2012). That is, if new technologies allow the interconnectivity that transcends geographic barriers, then why do TNC select specific locations for their several operations and not others (Barry, Görg, & Strobl, 2003; Kagami Tsuji, 2003; Rasiah, 2008)? Likewise, business concentrations in certain territories are growing and governments continue to promote special zones for their establishment (Porter, 1998, 2000), especially in Southeast Asian countries such as Malaysia and, more recently, in Vietnam. Interestingly, this phenomenon is not exclusive to manufacturing, but also take place in information and communication technologies and knowledge industries (Kagami & Tsuji, 2003; Mudambi, 2008; Sun et al., 2007; Zhou & Xin, 2003).

The characteristics of agglomerations and their links to global networks can vary according to development trajectories, the incentives set by policies, localization and territorial extension, foreign linkages and governmental cooperation, coordination mechanisms, and the dynamics of domestic competition (UNCTAD, 2013). Famous agglomerations in Southeast Asia respond to and are shaped by these factors. For example, the specialization in electronic equipment on Penang Island, Malaysia, is influenced to a great extent by market forces and government policies (Ernst, 2004; Iguchi, 2008; Wad, 2008): the Great Bangkok-Chachoengsao-Chonburi-Rayong automotive and electronics corridor can be explained by regional governments’ policies and cooperation, as well as by geographic advantages (Busser, 2008; Cooper, 2013; Techakanont, 2011), and the light-industry assembly clusters in Vietnam (auto parts, equipment, and components, electronics, textiles, and shoes) can be explained by government cooperation with foreign firms. The case of Singapore is special, because of its early focus on trade-related services. but also due to the flourishing of high-tech and high-value local firms in electronics, chemicals, and biomedical industries, which were able to become suppliers of leading global firms and later, become leaders themselves and developed their own regional networks (Dent, 2003; Yeoh, Sim, & How, 2007; Yeung, 2008). A common thread in all these cases is the great involvement of government at several levels.

As mentioned previously, Southeast Asian governments implemented policies that deliberately sought to generate industrial development centers. However, implementing such policies did not guarantee their success (Dixon, 1991; Ofreneo, 2008). Therefore, the relation between local or trans-border industrial clusters and the expansion of global-production networks is not clear in all cases. As Yeung suggests (2008, p. 83), “global production networks in different industries serve as the critical link that increasingly influences the economic fate and trajectories of development in specific regions and countries.” This is a symbiotic relationship in which national or regional economies could become a node of a larger international economic system, which in turn can shape the local conditions for its reproduction. This implies that each node would acquire some degree of specialization. In the case of East Asia, a World Trade Organization report (2011, p. 4) argues that,

The increasing fragmentation of value chains has led to an increase of trade flows in intermediate goods, especially in the manufacturing sector. In 2009, trade in intermediate goods was the most dynamic sector of international trade, representing more than 50 percent of the non-fuel world merchandise trade. This trade in parts, components, and accessories encourages the specialization of different economies, leading to a “trade in tasks” that adds value along the production chain. Specialization is no longer based on the overall balance of the comparative advantage of countries in producing a final good, but on the comparative advantage of the “tasks” that these countries complete at a specific step along the global value chain.

The challenge is that local producers need to be in the appropriate position to supply the goods and services according to the requirements of leading firms, for which institutional support, as well as financial, technical, and human capacities, are fundamental. Otherwise, if the leading TNC simply seeks to take advantage of the locational characteristics, physical infrastructure, or cheap labor, it tends to limit itself to bringing its own trusted supply network, which is often constituted by firms from same national origin, so that the contribution to local economic development might be minimal. This has been well documented for the case of Japanese and Korean TNC in Southeast Asia (Belderbos & Carree, 2002; Borrus et al., 2000; Byun & Walsh, 1998; Kuroiwa & Heng, 2008; McNamara, 2009; Simon & Jun, 1995; Tachiki, 2005; Techakanont, 2011; Urata, 1993).

Conclusions

Baldwin (2012) argues that the world economy is currently ruled by the dispersion of stages and not sectors (as it formerly was), so the new path to national industrialization would be accomplished by integration to a “fraction” of the global supply chains, rather than the sponsoring of whole production chains. The main implication of such a trend is specialization and, through that, to focus on national innovation and technological upgrade. Many governments in developing countries agree and are confident in this assumption, but not all of them have an absolute trust on markets to rule and drive industrialization and technological upgrade. In that respect, industrial policy is still necessary to fulfill the expectations of attracting GV&PC, because FDI alone rarely fills the technological and organizational gaps for developing economies to catch up. It is also clear that the institutional framework elaborated by a traditional notion of industrial policy would entail more than only subsidies, protectionism, and public spending.

East Asian countries have shown that, despite criticism of the role of foreign investment in domestic industrialization and technological upgrade, governments can make the best of GV&PC by coordinating economic actors through integrated industrial policies that purposely seek to control as many links of the production chain or nodes of the network as possible. From a political-economy perspective, specialization in few or in a single stage of the process could bring about a potentially harmful outcome of anchoring the economic structure in primary or labor-intensive sectors, but displacing opportunities to appropriate (high) added-value activities. None of the advanced industrial economies, the home of the companies that currently dominate global trade and investment through GV&PC, ever rested on a single role or structure (e.g., manufacturing or assembling), even those who had transited from a periphery to a central status of the international system, such as Japan in the 19th century and post-war Korea. As we argued earlier, an industrial policy in East Asia not only sought to join a specific fragment of the process, but rather incorporated into segments with positive spillover effects, aiming to gradually learn how to manage the whole process from A to Z. Therefore, the first lesson from developmental policies in Asia is that it is all right to focus on higher value-added segments, as long as local firms are involved or industrial policy clearly targets such a goal.

The second lesson of East Asian political economies is that industrial policies that cultivate technological and industrial clusters are effective in attracting international capital and become economic-growth engines, not only for jobs creation, but also as mechanisms to absorb industrial technology. This was accompanied by the development of domestic companies, which eventually could take over outsiders. Several studies have identified an increase of participation of Southeast Asian firms in global networks followed by an expansion of learning and industrial upgrade (Chaminade & Vang, 2008; Humphrey & Schmitz, 2002; Kimura, 2006; Mudambi & Navarra, 2002), particularly Singapore, Malaysia and, more recently, Vietnam.

However, we must reconsider the idea that clusters that entail the fragmentation of productive processes and the modularization of national economies (Cattaneo, Gereffi, & Staritz, 2010; Frigant & Lung, 2002; Sturgeon, 2006) comprise a desirable solution for engaging in the global economy. It could be that hyper-specialization as a consequence of fragmentation exerts as many negative effects in the long term as to relegate involvement in global networks to low-value economic “tasks”.

The argument here is different from the dominant idea that globalization spreads out production and that pursuing comprehensive sectoral development is economically unreasonable. According to such a perspective, national governments should limit themselves to follow engagement strategies in niches where their countries present comparative advantages. But if governments breed clusters only as magnets to bring about certain “tasks” or segments of the productive process, the risk of inhibiting the development of capacities would be great and perhaps difficult to revert. The latter could translate into a very limited contribution to economic and territorial development prospects and disables capacities for adjusting to international economic developments, such as the surge of competitors in the same fields and economic structures. Thailand’s automotive industry and Mexico’s electronics, automotive and aerospace sectors are good examples of this risk (Busser, 2008; Sajarattanochote & Poon, 2009). Nurturing capacities that allow knowledge accumulation to dominate other areas and stages of the production process, especially those with high technological content and added value, appear to be key policy goals for industrial catching-up.

Certainly, local firms in Southeast Asia have become inserted into global chains and networks, but it is necessary to review the quality of such an integration and the effects of human capital and technological formation. Especially if the cluster is created solely to host foreign firms, it is unlikely that knowledge and technology would be shared with local firms or transferred to TNC affiliates. Governments’ agencies may be complementary to the market as a source of information and knowledge, but they are certainly a difference maker. Southeast Asia and Latin America should learn from each other’s paths and mistakes and perhaps work together for common concerns of economic autonomy.

nova página do texto(beta)

nova página do texto(beta)