1. Introduction

There are various changes coming to international relations stemming from the conversion of global politics, which, in turn, influence international development cooperation working to reduce the gap between developing and developed countries since the Second World War. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) established the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) to help facilitate funding from traditional donor countries to developing countries to encourage economic growth.

More recently, a variety of new actors have emerged in several areas such as the private sector and newly established donor countries such as Mexico, as well as non-DAC donors and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Such increase is leading to the formation of a more diversified system. Moreover, because of the growing effects of interdependence and interconnectedness, the role of organizations such as the DAC have expanded and are now working to resolve global issues such as environmental problems and climate change, as well as food and financial crises (Jung, 2015). Such a trend is reflected in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), included in the post-2015 process of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), that are developing a comprehensive approach to social, economic, and environmental goals from a diversified perspective. In this sense, global tasks, which require cooperation of all the countries around the world including recipients as well as donors, are considered the key to the development issues.

Likewise, international development cooperation has already transcended the goal of "development" in developing countries and now incorporates the desire to help achieve both social and economic improvements. As such, its changing role now includes the establishment of comprehensive partnerships between developed and developing countries to jointly achieve sustainable development and global initiatives.

This research analyzes practical approaches to enhancing the partnership between South Korea and Mexico, by focusing on a participatory approach that is regarded as an important component in development cooperation. Therefore, this study draws mostly from interviews with relevant experts and documents provided by bilateral implementation agencies, such as KOICA and AMEXID.

As Professor Alfredo Romero pointed out, previous research on the rela tionship between South Korea and Mexico has been conducted by researchers from both countries and covers diverse areas including politics, economics, social issues, and culture (Romero, 2012). This research focuses on a more limited area of international development cooperation than previous research, and aims to present practical methods of cooperation by analyzing the rela tionship between both countries through a participatory approach.

South Korea transformed from a recipient country to a member of the OECD DAC donor list beginning in 2010 by adopting current DAC norms and standards.

While Mexico is currently included as a recipient country of the OECD DAC and classified as one of the upper-middle-income countries, it is expanding its role as an emerging actor. Mexico is not one of South Korea's Official Development Assistance (ODA) priority partner countries nor is it currently receiving any assistance in the form of a project-based intervention from the Korean government. However, Mexico could establish a method of cooperation with South Korea using development cooperation, while continuing to play an emerging role as a donor country in Central and South America.

In this regard, the objective of this research is to establish a new method of cooperation between South Korea and Mexico, based on a participatory approach newly discussed in the evolving development cooperation system.

As such, this research includes the following contents. Section 2 defines the approach of development cooperation system, using the concept of the expert-led and participatory approach. From a traditional perspective of development cooperation, it is possible to analyze the act of assistance as the expert-led and donor-oriented structure of South-North cooperation. However, due to the emergence of the various actors mentioned above and the increased effectiveness of the aid, the focus is moving towards horizontal cooperation and participatory approach between donor and recipient countries.

Section 3 analyzes the typical features and the position of South Korea and Mexico in accordance with the standards defined by the international community, from the perspective of international development cooperation and discusses the relationship between the two countries. Section 4 presents step-by-step, feasible strategy for both countries to facilitate collaboration by considering policy directions and methods of assistance in the cooperative development of South Korea and Mexico. The Conclusion establishes policy implications for expanding the future relationship in the area of development cooperation and considers its role in the partnership between the two countries.

2. Theoretical Framework and Background

With the increasing importance of new actors and global issues in the international development cooperation system, the relationship between donor and recipient countries is becoming horizontal rather than vertical (Jung, 2015). Meaning, in the previous system, the donor countries referred to the member countries of the OECD DAC, while recipient developing countries were included in the list of ODA recipients. Such recipient countries were considered to have relatively low levels of social development compared to developed ones (KOICA, 2013).

The emergence of new donors and global tasks, however, is altering the structure of development cooperation from South-North cooperation into that of the participatory approach that emphasizes South-South cooperation based on "cooperation" and "reciprocity" and the participation of recipient countries. In this way, development cooperation is becoming a new method of exchanging knowledge and enhancing the capability of developing countries by horizontal interactions between actors, rather than a one-sided transfer of knowledge through the vertical process (Morris, 2003).

This type of development cooperation may be divided into expert-led and participatory approaches, according to the different actors and the type of interaction between them. These concepts have distinct theoretical roots and differing emphases in terms of program orientation, objectives, and outcomes (Morris, 2003).

Table 1 Approach to international developmental cooperation: expert-led and participatory approach

Source: Servaes, 2011; Morris, 2003; Lennie & Tacchi, 2013.

The expert-led approach is a vertical and top-down system, which also refers to a "sender-receiver model". The participatory approach is an act of assistance with a horizontal structure. This method utilizes the concept of shared knowledge and a capability enhancement model, rather than the one-sided transfer of knowledge. In the expert-led approach, the lack of knowledge may be pointed out as an issue of recipient countries, whereas the lack of participation may be the issue in the participatory approach. In this sense, the information transmission and education may be regarded as the result of development cooperation projects in the expert-led approach. However, in the participatory approach, the focus shall be the "process" itself of such projects, information exchange and the capability enhancement of individuals, local communities and organizations in recipient countries. As such, the participation of local communities in the process of designing, implementing and evaluating the programs reflecting their needs, is more emphasized, rather than on outside intervention.

While these two approaches share complementary factors rather than conflicting ones, the focus has been moving from the expert-led structure to the participatory one in the current development cooperation system. Accordingly, development programs adopt participatory approaches, adapting to local contexts, promote sharing of information, mutual education, and work to build strategic partnerships with various stakeholders, including governmental bodies, the private sector, and international and local NGOs (Servaes, 2011). In this context, the purpose of development is to empower people to have control over the decisions that affect them and, in this way, foster social equity and democratic practices (Morris, 2013). Therefore, the participatory approach is an inclusive process and participation is regarded as not only the means of cooperation, but also the goal it (Lee, 2015).

3. The Relationship between South Korea and Mexico: International Development Cooperation

Mexico's Development Cooperation

As mentioned previously, Mexico has been a recipient country and, as such, has received Official Development Assistance (ODA) in the past from the international community. In addition, it is currently listed as an upper-middle-income country on the list of recipient countries of the OECD DAC. However, Mexico achieved stable economic growth in 1990s and has emerged as a new donor country.

In 2011, Mexico3 established the Mexican International Development Cooperation Agency (Agencia Mexicana de Cooperación Internacional para el Desarrollo, or AMEXCID) and enacted the Law on International Development Cooperation (Ley de Cooperación Internacional para el Desarrollo, or LCID), which provides legal certainty to the system. AMEXID, the institutional agency in which the affairs of the Mexican ODA reside, coordinates with relevant departments, designs policy, and conducts management tasks for international development cooperation.

This agency consists of an advisory body, a directive and administrative body, and a technical and financial body. Under the directive and administrative body, there are five executive departments, including General Direction of Education and Cultural Cooperation (DGCEC), General Direction of International Cooperation and Economic Development (DGCPEI), General Direction of Bilateral Cooperation and Economic Relations (DGCREB), General Direction of Technical and Scientific Cooperation (DGCTC), and General Direction for the Mesoamerican Integration and Development Project (DGPIDM). The DGCPEI and DGCREB are openly dedicated to the promotion of Mexican trade and are tasked with efforts to reduce the possibility that AMEXID'S policies, strategies, and actions are dedicated exclusively to international development cooperation (Prado, 2014).

While the agency is responsible for the maintenance of the system, it appears to lacks explicit strategies and functions at the agency level and is influenced by political change as well as external factors, such as foreign po licy in the framework of government to government interaction. To address these issues, the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) is implementing the Institutional Strengthening Project for AMEXID, which includes four fields of action: widening of the Mexican cooperation policy, intra-agency coordination, inter-agency coordination, and the development of cooperative tools and training for AMEXID'S specialists, directors, interlocutors and other stakeholders (Lázaro and Peláez, 2015).

Aside from AMEXID, there are other agencies in Mexico geared towards international cooperative development. For example, the Mexican System for International Development Cooperation, housed in the Programme for International Development Cooperation (PROCID), and develops strategies for the international cooperation of Mexico.The National Registration and Information System for International Cooperation for Development (RENCID) represents the statistical branch of cooperation. In addition, the National Fund for International Development Cooperation is the financial instrument that serves as a vehicle for financing the activities of the Mexican IDC (Lázaro and Peláez, 2015).

The special feature of Mexico's development cooperation is that it supports low-income countries in Central and South America, or South-South cooperation, serving as a bridge between North and South countries (Prado, 2015). It is also enhancing its partnership with upper-middle-income coun tries in Central and South America, such as Brazil, Argentina and Chile, and other DAC donor countries like Japan and Germany.

According to the OECD DAC statistics, Mexico received a total of USD 807 million from the ODA as a recipient country in 2014, which was 4% of total aid and the fourth largest amount, after Colombia (12%), Haiti (11%) and Brazil (9%) (OECD DAC, 2016a).

However, as displayed in Table 2, as a donor country, Mexico's international development cooperation reached USD 288.6 million in 2014. Mexico channeled 78% of its total funding cooperation through multilateral organizations. This amount includes technical cooperation offered through the exchange of experts including; scholarships to foreigners to carry out studies within Mexico, contributions to international organizations, humanitarian aid, the operation of AMEXCID, and non-refundable financial cooperation (AMEXID, 2016).

The AMEXID statistics of 2014 also indicate that Mexico conducted 330 technical cooperation initiatives, of which 196 (59%) were conducted through bilateral cooperation, with another 68 (21%) in multilateral cooperation, 39 (12%) in regional cooperation and 27 (8%) went to triangular cooperation schemes (AMEXID, 2016). The types of cooperation include short-term human resource exchanges, such as the invitation and dispatch of experts, as well as other forms including granting scholarships, hosting seminars, evaluating validity, and conducting joint research. The limits identified in the type of support appear in the dispatching of a small number of government officials or promoting organizations for only a short amount of time (1~2 weeks). As such, in the future, it is necessary to train human resources to send experts as well as secure a budget capable of supporting long-term commitments.

Until recently, Mexico promoted cooperative programs similar to those conducted by South Korea in its early stages of cooperative development. While Mexico's priority partner countries were mostly the countries in Cen tral and South America, Mexico plays both roles of a recipient and a donor country, thereby maintaining partnership with both groups.

According to the National Development Plan 2013-2018, international development cooperation is considered an effective diplomatic means to en hance Mexico's integration and participation in the international community. In addition, it helps to establish efficient partnerships with developed countries and international organizations and improves political and diplomatic relationships with other countries in Central and South America (Presidencia de la República, 2013). Moreover, Mexico is focusing on sharing or exchanging resources, knowledge, and experience with other countries and international organizations in the areas of education, culture, science technology, economy, and finance, within the framework of sustainable human development.

South Korea's Development Cooperation

South Korea's ODA has generally been described as a strategic tool for maintaining diplomatic relations with other countries and for achieving its po litical and economic objectives implicitly and explicitly (Jung, 2013). From the 1970s to the 1990s, South Korea was actively engaged as a donor in the international community, but the objective of its ODA was closely related to its economic interests. Therefore, the ODA was used as a method to promote exports and to expand its economic relations with other countries. As such, considerably more than half of the volume of its ODA funding was directed towards Asian countries (Jung, 2013).

South Korea was removed from the DAC List of ODA Recipients in 2000 and has been playing a role as a donor in the OECD DAC since 2010 (Jung, 2012; and López-Aymes, 2016). Recently, its ODA policies and strategies have been changing, as it is attempting to respect the needs of each partner country and complying with DAC standards, while the volume has expanded quantitatively.

The primary objectives of South Korea's ODA towards Latin America were motivated by a specific political factor. In the process of achieving independence from Japan within the context of the Cold War, South Korea sought to gain support from Latin American countries on issues related to North Korea within the UN (Jung, 2013). Beginning in the 1970s, however, its objectives began to focus more on economic aspects. Moreover, the ODA's attention on Latin America was insufficient and, as such, its policies changed in accordance to the new direction of the government.

Korea's ODA volume has increased for five consecutive years, from USD 1.17 billion in 2010 to over USD 1.85 billion in 2014 (ODA Korea, 2016a). Further, it has developed close ties with Asian countries, given its geographic proximity and cultural familiarity. Therefore, Asia received the largest portion of bilateral ODA funding (approximately 53%) during the past ten years (ODA Korea, 2016a). However, Korea has increased its allocations for Africa (to approximately 23.8%), while Central and South America received 7.8% of bilateral ODA funds in 2014 (ODA Korea, 2016a).

In this regard, Korea's ODA to Latin America has focused on reducing poverty and inequality, as well as support for sustainable socio-economic development. It has also proposed a principle of "selection and concentration," designated four priority countries, and formulated a Country Partnership Strategy (CPS). One of the South Korean government's ODA core policy efforts is directed towards the priority countries of Bolivia, Colombia, Paraguay, and Peru.

While Mexico is not one of Korea's priority partner countries, its government provided approximately USD 2.2 million to Mexico between 1991 and 2014, according to the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA) statistics. The types of support provided included technical cooperation, such as the invitation of trainees and the dispatch of experts, as well as emergency aid programs. Korea implemented only one project in the intervention category in Mexico. The project for constructing the Medical Center (Korea Mexico Friendship hospital) in Yucatan was established by the South Korean government, with it investing about one million dollars, to commemorate the centenary of the arrival of Korean immigrants to this region (KOICA, 2004).

More recently the two countries are promoting a joint-training program in the field of climate change and green growth within the framework of facilitating a system of horizontal development cooperation. South Korea has also introduced some reform and systematic measures to improve the effectiveness of its ODA. Further, as it is necessary for Korea to establish a comprehensive partnership with upper-middle-income countries or emerging donor countries such as Mexico, it is possible to enhance the effectiveness of assistance through a new support-based method using the participatory approach.

To generate more and better aid, the basic orientation of South Korea's ODA includes integrated strategy and coordinating system among stakeholders. The ODA is doing this through more frequent local level meetings, in an attempt to overcome the sender-receiver model, to share knowledge, enhance the capability of individuals and systems, as well as building a partnership with Mexico.

South Korea and Mexico: Development Cooperation and the Comparative Approach

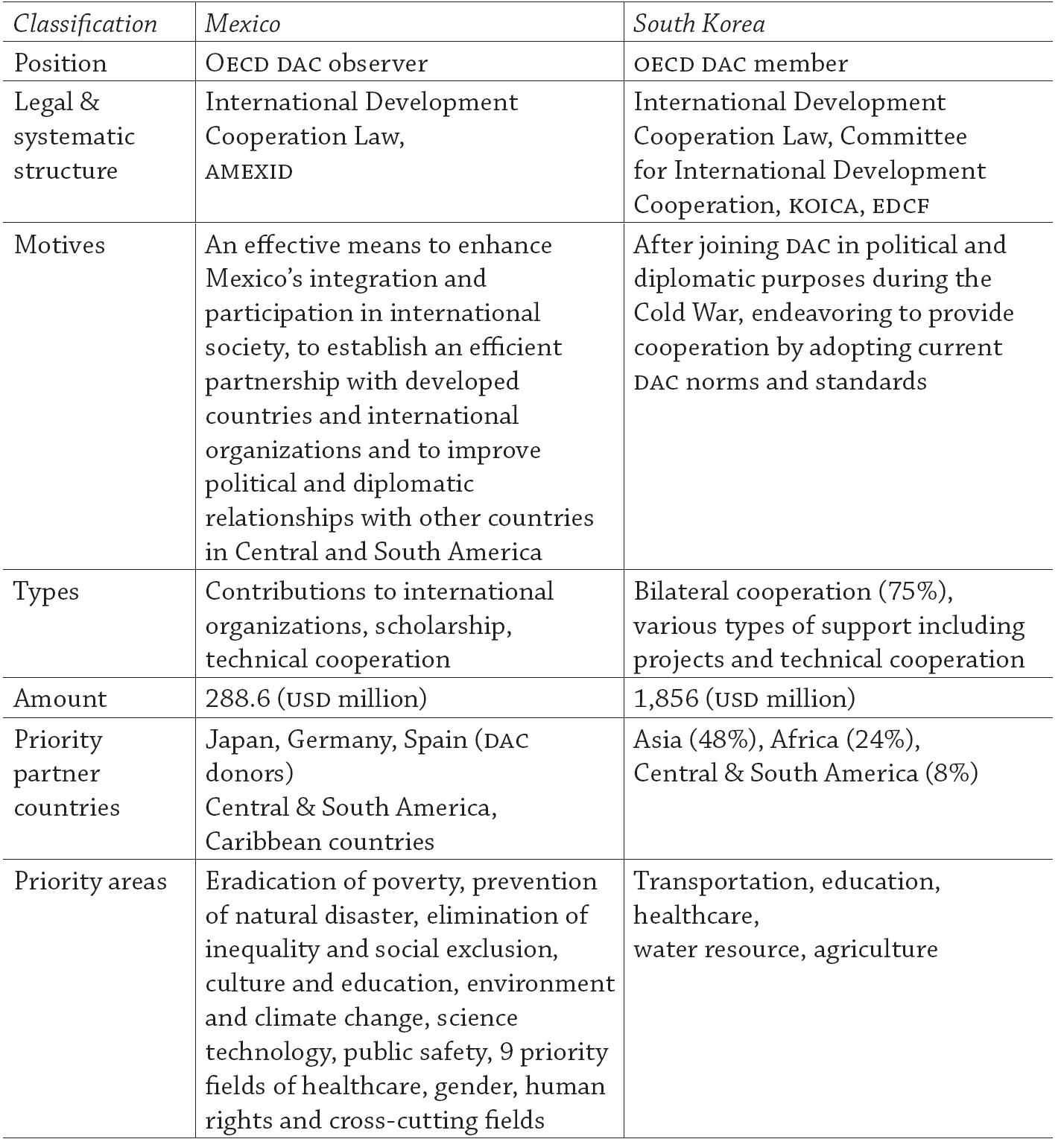

The Table 5 illustrates several aspects of the ODA cooperation between South Korea and Mexico from the perspective of development cooperation. It focuses on information concerning the position of the agency and the legal and systematic structures concerning the ODA. It also displays the motives of support as well as the major forms of cooperation. Lastly, it conveys the amount of support, the priority partner countries, and priority areas of cooperation between South Korea and Mexico.4

Table 5 Mexico and South Korea from the perspective of international development cooperation

Source: AMEXID, 2016; ODA Korea, 2016a; OECD DAC statistics, 2016b; Jung, 2014.

Mexico has been an observer of the DAC since 1994 and is a pivotal country in Central and South America. It is enhancing its influence in the region by expanding its cooperation with low-income countries as an emerging donor. Establishing the International Development Cooperation Law and AMEXID in 2011, Mexico created the legal and systematic structures for development cooperation. In addition, it considers development cooperation to be a diplomatic investment and seeks to establish partnerships with the international community and developed countries to strengthen its political and diplomatic influence in Central and South America. Mexico promotes development cooperation based on three types of partnership, including partnership with DAC donors, emerging donors, and recipient countries.

Meanwhile, South Korea established the Economic Development Cooperation Fund (EDCF) in 1987, KOICA in 1991, and enacted the International Development Cooperation Law and joined DAC in 2010. The Committee for International Development Cooperation (CIDC) was also founded for coordination purposes in 2006.

The ODA in South Korea is directly related to the U. S. policy toward East Asia during the Cold War. Development cooperation after the Cold War took on an important role in the economic growth of South Korea. Since joining the DAC in 2010, South Korea has promoted a wide range of reforms and, in an effort to abandon previous political and economic motivations of support, provides support for the economic and social advancement of developing countries (Jung, 2012).

In 2014, Korea provided USD 1.85 billion, which is 0.13% of its GNI (oda Korea, 2016). While not as robust, as an emerging donor country, Mexico's international development cooperation reached USD 288.6 million in the same year. While most of the priority partner countries of Mexico are in Central and South America, South Korea's are in Asia (48%) and Africa (24%) (ODA Korea, 2016). Mexico's priority fields include eradication of poverty, prevention of natural disaster, elimination of inequality and social exclusion, culture and education, environment and climate change, science technology, public safety, healthcare, gender, human rights, and other cross-cutting fields (AMEXID, 2012). In comparison, South Korea supports social and economic development, such as transportation, education, healthcare, water resourcing, and agriculture.

As established above, Mexico has the capability of mitigating the limits that may occur from the development gap between low-income countries in Central and South America and developed donor countries, as well as providing expertise in various project-promotion organizations, technology, and human resources. At the same time, Mexico also accumulates the experience of support in South-South cooperation and triangular cooperation, in which it may support other developing countries based on bilateral cooperation with Germany or Japan.

The previous support was limited, however, to short-term cooperation, such as dispatching experts, joint training programs, and workshops and seminars. The two countries are currently seeking to establish a legal and systematic foundation to create medium- and long-term partnerships by drafting Memorandums of Understanding (MOU). However, as there exists no branch or office dedicated to this kind of development in Mexico, like the KOICA, it is necessary to create a local-level system to promote, direct, and coordinate communications, projects, and funds. Even though no such office exists in Mexico, the two countries have implemented joint training sessions through on-line training and workshops in areas such as environmental issues like green growth and climate change. In addition, they are working on a proposal for triangular cooperation to support 10 countries in Central and South America, including Belize, Columbia, Panama, and Costa Rica.

4. The Mexico-South Korea Strategy: The Participatory Approach in Development Cooperation

Utilizing the participatory approach, this section identifies a step-by-step strategy for cooperation between South Korea and Mexico. In the first step, both countries should promote projects within the framework of bilateral, intergovernmental consultations or existing cooperative agreements. In doing so, each country could utilize technical cooperation, such as international training conducted by AMEXID and establish a Korea-Mexico joint training model promoted by KOICA. For example, Korea could expand its support to other recipient countries in Central and South America by fostering joint training with Mexico. This type of cooperation could reduce the difficulties surrounding administrative efforts as well as save time in the early stages of development, while still utilizing the previously established promotion system. It should also create opportunities to introduce South Korea's development cooperation support models to other countries in Central and South America. It would then be possible to expand the current focus on environmental areas such as climate change and green growth, toward other areas such as healthcare, agriculture, water resource management, and education. It would also possible to offer innovative training sessions and courses through analyzing the demand of Mexico's priority partner countries, as well as Korea's ODA partner countries in Central and South America. In doing so, experts from Mexico and Korea could promote training programs for experts from recipient countries in Central and South America to promote organizations in Mexico. Specifically, the participatory approach could produce medium- to long-term training programs designed to enhance capabilities and facilitate the sharing of knowledge. In addition, by holding local-level, working seminars and policy conversations on a regular basis, horizontal interactions may be utilized.

This kind of empowerment process tends to support training and educational programs, which have focused not simply on technical skills, but also on establishing institutional changes in the relationship between stakeholders (Oswald and Ruedin, 2012). Table 6 emphasizes the need to consider holistically the capacity of individuals and organizations to build relationships through system and network development.

For the second step of participatory development, South Korea should promote direct, bilateral programs within Mexico. South Korea has successfully supported the construction of medical center in Yucatan through the Ministry of Healthcare of Mexico in 2003-2004 (KOICA, 2016). As such, it is possible for the country to provide direct support to Mexico for bilateral programs in the future. Experts from Mexico, rather than South Korea, could work for the program or the program could work to enhance their own capabilities and empowerment. In addition, Korea should support current Mexican cooperative programs in Central America for recipient countries by supplying knowledge, technology and guidance, as well as financial support. Moreover, experts from Mexico could, in turn, work to develop programs for Korean partnerships in countries such as Guatemala, El Salvador, Bolivia, and Paraguay to enhance the effectiveness of developing cooperation programs.

Table 7 Mexican cooperation programs with Central America

Source: Internal documents of AMEXID, 2014.

In the third step, Korea should solely or jointly sponsor funding for re gional development in Central and South America, thus expanding the partnership between the two countries. Additionally, AMEXID manages various types of bilateral and regional funds, such as the Mexico-Spain Joint Fund, the Mexico-Chile Joint Fund and the Regional Fund for the Promotion of Triangular Cooperation in Latin America and the Caribbean. The majority of them are dedicated to mobilizing financial resources to boost socio-economic development, enhance human resources, coordinate multi-stakeholders, etc. (Lázaro-Ruther and Peláez-Jara, 2015).

However, to generate bilateral funding, a legal and systematic foundation must be created to provide funding in Korea to facilitate projects promoted by AMEXID. For example, in the Central and South American and Caribbean fund, promoted by the German Agency for International Cooperation (GIZ), the recipient countries in Central and South America would design the pro jects, and then be required to have detailed discussions with a branch office of the GIZ, which will in turn provide consultation on outlines and standards of the project. Subsequently, the plan for the project must be submitted to the Embassy of Germany and BMZ will review and approve projects in accordance with validity and effectiveness. Finally, BMZ would notify the local office of GIZ of the decision on the project and GIZ, the donor country and the recipient country would then work together to promote the project based on the discussions (GIZ, 2014).

In this context, both South Korea and Mexico would be required to establish a foundation on which to conduct such procedures. If a legal system is established in Mexico to create such bilateral funding with South Korea, Korea would then be in a position to support Mesoamerican projects and regional programs promoted by AMEXID for the medium-to long-term by committing needed funding to AMEXID. At a later stage, work plans specifying activities, intermediated objectives, and outcome indicators can be negotiated at the project level. Accordingly, funding must ensure connectivity and constant communication between stakeholder-groups. More specifically, high-level political commitment is crucial to help ensure visibility and establish the necessary support for transforming such funding into a strong and strategic international development cooperative tool (Lázaro and Peláez, 2015). As such, the program should promote an open, dialogue-oriented organizational culture, and establish information exchange as an integral part of human resource development.

5. Conclusion

This research analyzed the relationship between Mexico and South Korea, focusing on the area of international development cooperation.The research thus examined a variety of changes taking place in development cooperation resulting from the trend towards globalization, and evaluated the traditional features and relationship between South Korea and Mexico.

Finally, based on the participatory approach as a strategy for cooperation between South Korea and Mexico, the research suggested joint training programs to expand existing partnerships in the first stage, joint support to programs promoted by both countries in the framework of bilateral cooperation in the second stage, and further financial support by allocating funding in the third stage.

As mentioned previously, AMEXID, the organization in charge of development cooperation in Mexico, plays the dual role of donating and receiving funding, as well as maintaining a systematic structure. However, AMEXID is still in an early stage of development and shows a lack of experience and systematic competence. As such, it is charged with coordinating between departments, while executive departments promote the actual projects. In addition, since branch offices have not been established in partner countries, its officials usually work in embassies and are sometimes criticized for slow responses, lack of expertise and bureaucracy. Further, because the budgets for each project have not been allocated, it is difficult to maintain stability and consistency with funding. Moreover, the short-term technical cooperation such as short-term training, granting of scholarships, dispatching experts and hosting workshops and seminars, made it difficult to establish long-term policy directions for competency development.

Meanwhile, Korea has recently worked to organize a legal and systematic structure for the ODA as a donor and has endeavored to implement a wide range of reforms in accordance with the DAC regulations and policy directions. Still, it lacks a foundation from which it could promote actual cooperation between the two countries. Therefore, it is important to establish one to improve participation and discussion among various actors to utilize the participatory approach. It is especially important that Korea play the role of facilitator rather than an active actor in its relationship with Mexico, focusing on the relationship between the other actors and the implementation of projects. Likewise, the most important aspect of the relationship between two countries engaged in the participatory approach is to develop a procedural and a communication system to enhance the long-term relationship between the two. Unlike the Korean government, from President Felipe Calderon's administration to President Enrique Peña Nieto's, it has been argued that the Mexican international development cooperation was not politically supported, and thus the institutionalization process was slow (Prado, 2014).

To conclude, international development cooperation has traditionally been considered a relationship between developed and underdeveloped counties, stemming from the South-North cooperation framework. More recently, the South-South role of international development cooperation has become increasingly important.Therefore, it is necessary facilitate cooperative development to promote and coordinate bilateral cooperation and communication concerning global issues. In addition, efforts to increase and strengthen the capacity of sustainable development between established and emerging donors such as South Korea and Mexico are needed.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)