Given the nature of romantic relationships, it is likely that people will hurt and be hurt by their partner’s behavior, at some point in time. It has been documented that the amount of damage people experience in these relationships is more severe than in other interpersonal contexts (Leary et al., 1998). Furthermore, people hurt by their romantic partner tend to experience feelings of hostility, desire for revenge (Shackelford et al., 2000), depressive symptomatology, anxiety (Cano & O’Leary, 2000), and even post-traumatic stress (Sabina & Straus, 2008). They also engage in behaviors that endanger their health, such as eating less than before (or even not eating at all), consuming more alcohol or marijuana, over-exercising, and having sex under the influence of drugs or alcohol (Shrout & Weigel, 2018). However, there is also evidence of people who improved their relationship as a result of the transgression (Schratter et al., 1998), and although there is abundant research supporting that forgiveness is essential the process of emotional healing of individuals and couples (e.g., Guzmán-González et al., 2019; Jensen et al., 2021; Miller & Worthington, 2010; Zandipor et al., 2011), coping may be key to understanding why some persons forgive, while others don’t.

According to the transactional model of stress and coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1991), differences in the psychological adjustment in post-transgression dynamics may be due to the use of different coping strategies. This theory has been applied in a wide variety of studies and areas (Zeidner & Endler, 1996). However, strategies to cope with an interpersonal transgression committed by the romantic partner only have begun to receive attention (e.g., Jeter & Brannon, 2016; Rosales, 2018; Strelan & Wojtysiak, 2009).

The development of scales to measure coping strategies used in the face of a partner’s transgression is in its early stages. So far, some studies used adaptations of measurement instruments but did not present validity evidence, while others show unacceptable reliability coefficients, so their findings should be interpreted with caution (Jeter & Brannon, 2016; Strelan & Wojtysiak, 2009). Later, Rosales (2018) developed an Inventory to measure coping strategies in this context, which consists of three scales: (a) The emotion-focused coping scale (E-FCS), (b) the meaning-focused coping scale (M-FCS), and (b) the problem-focused coping scale (P-FCS), which seem to have good psychometric properties, although only Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and internal consistency analysis through Cronbach’s alpha have been conducted.

Therefore, this research aims to test the construct validity of the coping strategies inventory in the face of a transgression committed by a partner (Rosales, 2018), and then to explore its relationship with forgiveness and resentment. To do so, we tested the original factor structure of the inventory (E-PCS, P-FCS, and P-FCS) through confirmatory factor analysis techniques, as well as internal reliability through the Omega coefficient, and then conducted statistical correlations with forgiveness and resentment scales. According to theoretical and empirical background, such coping strategies should be associated with forgiveness and resentment.

Interpersonal transgressions as stressful events

Interpersonal transgressions are stressful experiences in people’s lives. Based on the contributions of Jones et al. (2001) and Worthington (2006), we conceptualized an interpersonal transgression as an action - carried out by someone else - in which a person’s physical, psychological, or moral limits are violated, and consequently the person feels injured or offended. There is scientific evidence that transgressions are interpersonal stressors, which threaten the transgressed person’s well-being, and might exceed their resources to cope with such mistreatment (Lazarus & Folkman, 1991).

Reactions are not only psychological biological stress indicators that are triggered by thinking about an interpersonal transgression. McCullough et al. (2007) measured salivary cortisol during 14 days in people that had recently experienced a transgression (e.g., betrayals of confidence, romantic infidelity, property damage, and physical or emotional harm), and found that the participants who reported ruminating about the transgression had higher levels of cortisol. These biological changes may be due to the lack of perceived coping skills to handle such stress (Sladek et al., 2016).

Transactional model of stress and coping with interpersonal transgressions: Three coping dimensions

Stress reactions are not intrinsic to adverse situations, but rather the result of the individual’s appraisals. According to Lazarus and Folkman (1984), people do a primary and a secondary appraisal of their romantic partner’s transgressive behavior, the former evaluates the transgression’s significance for their personal well-being, and categorizes it as stressful when they have already suffered some damage (harm/loss), or if damage has not yet occurred, but it is anticipated (threat), or even if the person focuses on the potential for gain or growth from the transgression (challenge). The latter evaluates what can be done to deal with the internal and external demands of the transgression, whether a given coping strategy will work for a particular purpose or not, and if the person is able to apply it effectively, that is, if the person considers themselves to have enough resources to cope with the transgression.

Once the person appraises the interpersonal transgression as taxing or exceeding their resources, diverse coping strategies emerge to restore or protect the individual’s welfare. Coping is defined as all the cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage the specific, internal and/or external, demands of a stressful situation (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Coping may have different functions, depending on which internal or external demands the person is trying to manage. In terms of external demands, problem-focused coping is directed at objectively managing or altering the stressful situation, while for internal demands, emotion-focused coping is directed at regulating emotional responses to the problem (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Meaning-focused coping is directed at finding a new meaning to the stressful situation (Park & Folkman, 1997). Even though these three general dimensions of coping are well studied, it’s necessary to account for the specific strategies actually used to deal with an interpersonal transgression.

Coping must be assessed within the specific context of whatever people are actually coping with, that is, coping measures must account for what people actually think or do in a specific context (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Rosales (2018) conducted a qualitative study to identify how people cope with a transgression committed by a partner, the author interviewed 180 people who had experienced a transgression by their current partner, and identified strategies aimed at emotional control, modifying the meaning of the transgression, as well as the conditions that led to the transgression in order to prevent similar events in the future. Subsequently, based on the information collected, they developed items that gave rise to the Inventory of coping strategies in the face of a transgression by the romantic partner.

The following are the definitions that Rosales (2018) proposes of the different types of coping strategies in the context of the transgression committed by the partner. (a) Emotion-focused coping are those strategies carried out to diminish the level of emotional distress due to the transgression. Such as physical avoidance of the transgressor, attempts to think about other things instead of the transgression, efforts to control negative emotional states raised from the mistreatment, venting the situation with a trusted person, or going for a run or other kind of physical exercises; (b) Meaning-focused coping represents a cognitive reappraisal that modifies the way the person experiences a transgression, were they reevaluate the importance and consequences, as well as the responsibility and intentionality of the transgressor; (c) Problem-focused coping is an effort to objectively describe the transgression in an attempt to have a clearer vision of it. Identifying the causes, looking for restitution for the harm caused by the transgressive behavior, and carrying out actions and agreements with the romantic partner to prevent similar incidents in the future. Table 1 presents the definitions of the factors included in the scales for measuring emotion-focused, meaning-focused, and problem-focused coping.

Table 1 Factors, definitions and item examples of the E-FCS, M-FCS and P-FCS

| Scale | Factors | Definition | Item examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotion Focused Coping Strategies (E-FCS) | Distressed Behavioral Expression | Behavioral efforts to reduce emotional distress through its exacerbated expression | I start yelling; I start attacking; I act violently |

| Self-control | Efforts to manage and suppress emotional reactions and impulses. | I try to stay calm; I take a breath to relax; I distract myself by doing other things | |

| Social Support | People seek relief from their emotional distress by disclosing their experience of transgression to people they trust. | I talk about it with a friend; I talk about it with people close to me | |

| Physical Activation | Physical exercise which aims to reduce emotional distress rather than maintain or improve physical condition. | I go for a run; I start exercising | |

| Time-Outs | The person seeks physical avoidance from the romantic partner for the time necessary in order to calm down. | I put my distance from him; I move away from my partner | |

| Meaning Focused Coping Strategies (M-FCS) | Relationship Maturation | A cognitive reappraisal in which the transgression is now seen as an event that benefited the relationship. | It made us mature as a couple; It was useful to change some aspects of the relationship |

| Minimization of transgression | A cognitive reappraisal in which the transgression is considered less severe or important. | Now I think it was no big deal; Now I think it was all nonsense | |

| Relationship Deterioration | Transgression is interpreted as an event whose negative consequences are still affecting the relationship, reducing its value. | It is destroying our relationship; It made the relationship colder | |

| Problem Focused Coping Strategies (P-FCS) | Negotiation | Actions in which both members of the dyad expose their position regarding the transgression and reach agreements that are directed to compensate the consequences of the transgression and to prevent future incidents | We reach agreements by talking; We work together to move forward; We changed what we needed to |

From our literature search, this is the first research attempt to define each dimension of coping strategies in the context of a transgression committed by the romantic partner, however psychometrically it is also important to test how the construct relates to other relevant constructs (Dimitrov, 2010), and both forgiveness and resentment may be closely related.

Coping and Interpersonal Forgiveness

Although the study of coping strategies for interpersonal transgressions is recent, it is possible to trace similar approaches within the forgiveness literature. The Biopsychosocial Stress-and-Coping Theory of Forgiveness (Worthington, 2006) conceptualizes transgressions as stressful events and establishes that forgiveness is an adaptive coping strategy, since it is related to higher levels of physical health (Cheadle & Toussaint, 2015), well-being (Witvliet & Root Luna, 2018), mental health (Griffin et al., 2015), and lower levels of addiction and suicidal risk (Webb & Toussaint, 2019). However, given that these findings have been primarily at the correlational level (i.e., people who reported better mental health also had higher levels of forgiveness), it has been pointed out that forgiveness might not be a coping strategy per se, but rather an outcome of implementing certain strategies (Strelan, 2019). Therefore, given the central role of forgiveness in the study of post-transgression dynamics, it is necessary to study forgiveness and coping strategies as different constructs, although according to the theoretical background, they should be related, and their relationship might contribute to the construct validity of the Transgression Coping Strategies Inventory (Dimitrov, 2010).

Forgiveness is characterized by emotions, cognitions, and behaviors that denote positive affect toward a person despite their detrimental behavior, while resentment is characterized by emotions, cognitions, and behaviors that denote negative affect toward a person due to their damaging behavior (Rosales-Sarabia et al., 2018), and according to Worthington and Scherer, (2004) theoretical framework, forgiveness should be positively related to emotion-focused coping because the offended individual attempts to deal with the negative emotions elicited by the transgression, facilitating emotional juxtaposition (i.e., the shift from negative affect to positive affect), similarly through problem-focused strategies the offended individual attempts to bring about justice and decrease the perceived injustice gap, and finally meaning-focused strategies in which the transgression is reappraised to seem less offensive or even non-offensive. However, there’s a lack of empirical studies in this area.

In this research, we assessed the construct validity of the inventory of coping strategies with an interpersonal transgression committed by the romantic partner and tested its external relationship with forgiveness and resentment. The inventory consists of three scales: (a) The emotion-focused coping scale (E-FCS), (b) the meaning-focused coping scale (M-FCS), and (c) the problem-focused coping scale (P-FCS), we tested those factor structures through Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), and performed correlations on each coping scale with forgiveness and resentment measures. Ultimately, we aim to provide evidence on the validity and reliability of the inventory, so we can more accurately understand the implications of coping strategies on the physical and mental health of the individuals and the quality of their relationships.

Method

Participants

Using an accidental non-probabilistic sampling technique, 300 participants were recruited. 213 (71%) were women and 87(29%) were men; the age ranged from 18 to 80 years old (M = 29.51%, SD = 12.57), all within a romantic relationship (23% Marriage, 59% Dating, 13.3% Free Union, and 4.7% Other). All individuals who participated in the study did so voluntarily and with the guarantee of absolute confidentiality and anonymity of their information.

Procedure

Participants were recruited in public recreation sites in Mexico City and the metropolitan area. By assuring the anonymity and confidentiality of their information, voluntary collaboration was sought from the people who met the criteria of being at least 18 years old, being involved in a romantic relationship, and having been hurt by a transgression committed by their current romantic partner at some point of the relationship. Those who agreed to participate were given a questionnaire that asked them to describe the most important transgression they had received from their partner and the magnitude of the damage experienced at that time. Subsequently, they were instructed to answer the scales, taking into account the previously described transgression. When participants finished responding to the scales, their collaboration was verbally thanked.

Instruments

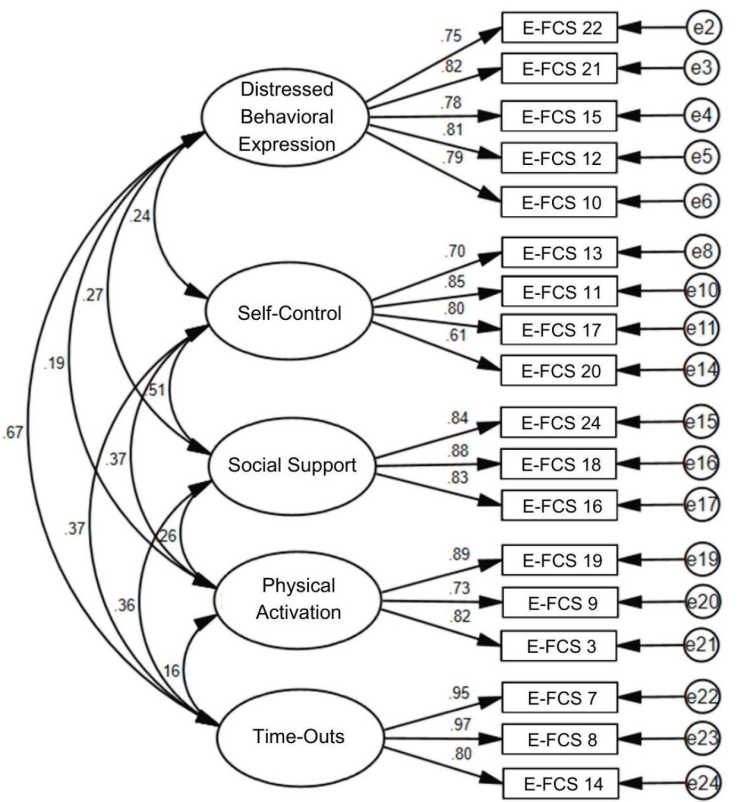

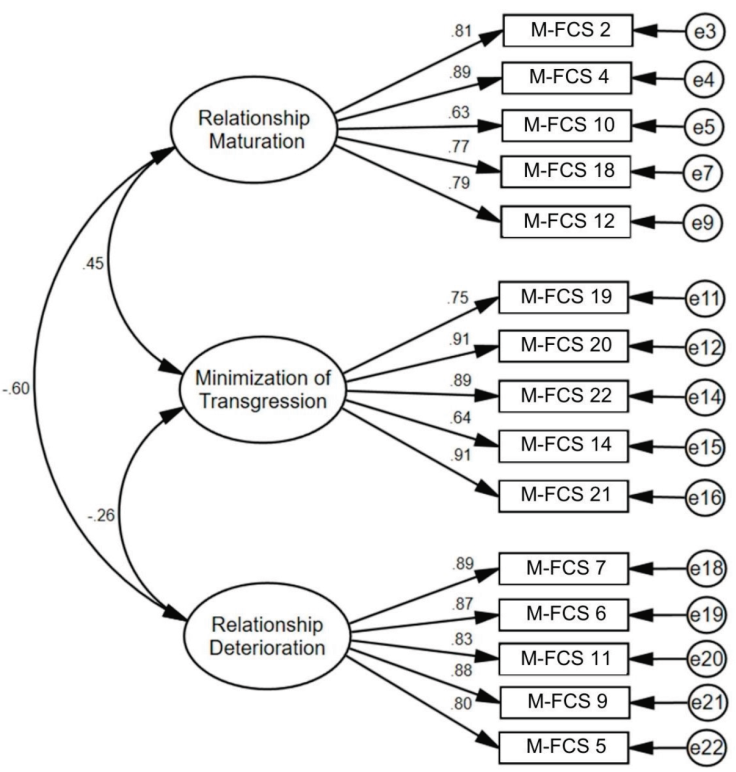

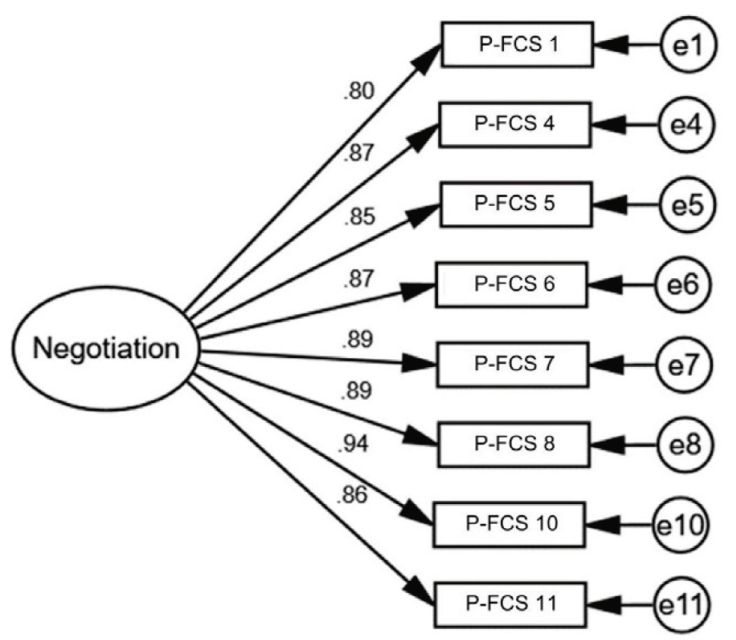

We used the inventory of coping strategies in the face of a transgression committed by a partner (Rosales, 2018), which consists of (a) The Emotion-Focused Coping Strategies Scale (E-FCS), which consists of 24 items grouped into five factors: Distressed Behavioral Expression (α = .92), Self-Control (α = .86), Social Support (α = .92), Physical Activation (α = ..88), and Time-Outs (α = .87), which account for 62.05% of the variance, with an overall internal consistency of .91; (b) The Meaning-Focused Coping Strategies Scale (E-FCS), consists of 22 items grouped into three factors: Relationship Maturation (α = .93), Minimization of Transgression (α = .90), and Relationship Deterioration (α = .90), which account for 59.56% of the variance, with an overall internal consistency of .87; And the (c) Problem-Focused Coping Strategies Scale (E-FCS), consists of 11 items grouped into a single factor: Negotiation (α = .94), which explains 60.95% of the variance. The three scales have a Likert-type response format ranging from 1 to 5 (1 = never, and 5 = always).

Forgiveness and resentment were measured using the Forgiveness and Resentment Towards Partner’s Transgressions Scales (Rosales-Sarabia et al., 2018). The forgiveness scale has five factors (positive affect, benevolence, positive cognition, compassion, and positive behavior), accounting for 57.56% of the variance, and with a global internal consistency of .95. Resentment scale showed four factors (negative cognition, negative affect, avoidance, and revenge), explaining for the 50.38% of the variance, with a global Cronbach’s alpha index of .91. However, a second order factor analysis between the nine factors of both scales showed a bifactorial solution in which both forgiveness and resentment were grouped as two separate factors, accounting for the 79.10% of the variance (Rosales, 2018). For this study, forgiveness and resentment global scores were used rather than their factors.

Data analysis

All CFA models were tested with Maximum Likelihood estimation, and the fit was assessed according to Hu and Bentler’s (1999) cutoff suggestions using a combination of Bentler’s Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). Satisfactory model fit occurred when CFI and TLI showed values equal or greater than .95, and RMSEA values were less than .06. The only exception was the P-FCS which given its unidimensionality and few degrees of freedom, RMSEA might falsely indicate a poor fitting model (Kenny et al., 2015), so we used the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) index, which cutoff value should be less than .08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). We assessed the questionnaires’ internal consistency using the Ω coefficient (McDonald, 1999) and Hayes’ (2018) Process Macro for SPSS. Finally, we performed Pearson correlations to examine the relationships between coping strategies, forgiveness, and resentment.

Results

Overall, we found that E-FCS, M-FCS, and P-FCS replicated their underlying structure and models met satisfactory fit, however, some items were deleted through the CFA process since they were redundant or presented low factor loadings, no error covariances were computed. The fit indices for E-FCS model (see Figure 1) were CFI = .962, TLI = .953, RMSEA = .059; fit indices for M-FCS model (see Figure 2) were CFI = .973, TLI = .967, RMSEA = .059; finally, fit indices for P-FCS (see Figure 3) were CFI = .962, TLI = .947, SRMR = .025. All fit indices are considered adequate according to the cut-off points proposed by Hu and Bentler (1999). Validated versions are available in exhibits one, two and three (see Annex).

In general, most coping scales factors were slight to moderately correlated with forgiveness and resentment (see Table 2). Emotion-focused strategies such as distressed behavioral expression, physical activation, and time-outs showed negative correlations with forgiveness, and positive correlations with resentment while seeking social support was only associated with greater resentment toward the partner. Regarding the meaning-focused strategies, relationship maturation was a positive correlate of forgiveness, although negative of resentment, and relationship deterioration was negatively associated with forgiveness and positively with resentment, while a greater minimization of transgression was associated with higher levels of forgiveness. Finally, in terms of problem-focused strategies, negotiation was positively correlated with forgiveness and negatively correlated with resentment.

Table 2 Means, standard deviations, omega indices and intercorrelations for scores on the Forgiveness, Resentment, E-FCS, M-FCS and P-FCS

| Factor |

|

Ω | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Forgiveness |

|

.95 | ___ | -.630** | -.342** | 0.072 | -0.13 | -.139* | -.390** | .480** | .215** | -.440** | .547** |

| 2. Resentment |

|

.93 | ___ | .538** | 0.064 | .247** | .207** | .504** | -.347** | -0.054 | .563** | -.494** | |

| 3. Distressed Behavioral Expression |

|

.90 | ___ | 0.09 | .313** | .248** | .642** | -.266** | 0.075 | .619** | -.424** | ||

| 4. Self-Control |

|

.82 | ___ | .390** | .431** | .252** | .302** | .133* | 0.105 | .195** | |||

| 5. Social Support |

|

.85 | ___ | .300** | .322** | 0.036 | 0.084 | .330** | -0.032 | ||||

| 6. Physical Activation |

|

.88 | ___ | .352** | 0.109 | .194** | .240** | -0.057 | |||||

| 7. Time-Outs |

|

.87 | ___ | -.258** | .126* | .589** | -.442** | ||||||

| 8. Relationship Maturation |

|

.90 | ___ | .471** | -.471** | .763** | |||||||

| 9. Transgression Minimization |

|

.85 | ___ | -0.07 | .337** | ||||||||

| 10. Relationship Deterioration |

|

.89 | ___ | -.602** | |||||||||

| 11. Negotiation |

|

.93 | ___ |

Note. *p < .05. **p < .01.

Discussion

This study tested the psychometric properties of the E-FCS, M-FCS, and P-FCS. Construct validity evidence was obtained through the replication of their factor structure through CFA, the findings suggest an adequate construct validity for each scale. Likewise, the scale’s reliability was stronger than others available in the literature (e.g. Gates, 2012: Jeter & Brannon, 2016). In contrast with previous theoretical foundations, emotion-focused strategies generally were negatively associated with forgiveness (c.f. (Worthington & Scherer, 2004), while -as expected- meaning and problem-focused strategies were mostly positively associated. The three scales showed factors that integrate harmoniously within the coping theoretical framework, and previous measurement instruments, show convergent and divergent validity with other variables, and bring a specific operationalization for the post-transgression context.

Emotion-Focused Coping Strategies Scale

Analyses of the E-FCS replicated five factors, of which distressed behavioral expression, self-control, social support, and physical activation are similar to factors reported in previous studies (Barra, 2004; Carver et al., 1989; Moos, 1993), however time-outs seem to be new in the field. Distressed behavioral expression has been widely described as the consequence of a threat appraisal of a stressor (Lazarus & Folkman, 1991), and constitutes the least adaptive way of coping with stress. Self-control was initially proposed in the seminal work of Lazarus and Folkman (1991) as a coping strategy focused on emotion, however, we did not find a previous coping scale that accounts explicitly for it. Social support is also recognized as an emotion-focused coping strategy (Barra, 2004), since talking about the event with another person may have an emotional discharge and relief function. The physical activation or exercise coping strategy has been reported in the scientific literature, but it has only been operationalized with a single item in previous research (e.g., Harris et al., 2006), and although its study comes from the health area rather than a social setting, our study provides a set of items which accounts for the use of physical exercise as a way to reduce the emotional affliction caused by an interpersonal transgression. Also, time outs might be a way to deal with the negative emotions derived from the transgression, as a strategy involving the physical withdrawal from the partner in order to cool down the emotions, and -perhaps- prevent further negative consequences. However, contrary to the previous theoretical background, it seems that these coping strategies could prevent the forgiveness process.

Emotion-focused strategies aim to reduce and control negative emotions, which should boost emotional juxtaposition, since according to Worthington and Scherer (2004), the reduction of negative emotions (resentment) eases an increase in the experience of positive emotions (forgiveness), however our results do not seem to point towards such direction. Although this subtractive approach is clearly compatible with the basic premises of cognitive behavioral therapy (Hazlett-Stevens & Craske, 2002; Leder, 2017), it has been reported that such efforts to suppress negative emotions can constitute a pattern of experiential avoidance and - paradoxically - amplify them (Farr et al., 2021; Hayes et al., 2004). Experiential avoidance actions tend to focus on reducing these emotions in the short term, but at the cost of more negative consequences in the long term (Bardeen, 2015), for example during an episode of anger, a person angry with his partner may yell at her and offending her intensely, resulting in short-term emotional relief, but at the cost of further relationship deterioration. Hence, it is plausible that the relief function might be the reason why the distressed behavioral expression, social support, physical arousal, and time-outs are negatively associated with forgiveness and positively associated with resentment.

Meaning-Focused Coping Strategies Scale

The M-FCS factors represent the cognitive reappraisal of the transgression, which can be positive or negative. Relationship maturation is a kind of positive reinterpretation (c.f., Carver et al., 1989) or reappraisal (Moos, 1993), in which the incident is seen as an event from which the relationship improved, so positive consequences were obtained from a negative event. Besides, the minimization of the transgression factor, implies a less negative primary reappraisal of the incident, by remembering the transgression with lesser importance ( c.f., Lazarus & Folkman, 1991). In contrast, relationship deterioration seems to be a factor in which the transgression reappraisal is characterized by being more negative, and costful for the relationship across time. People might actively use these strategies to deal with the stress (i.e., self-verbalizations), but also constitute part of a wider process in which emotion, problem, and meaning strategies are occurring and interacting at the same time, along with forgiveness and resentment.

Relationship maturation and transgression minimization were positively related to forgiveness, and although the cross-sectional nature of this study does not allow for causal inferences, it is possible to hypothesize processes to explain these relationships. Understanding that although the transgression was a negative event for the couple, it allowed them to grow, implies -to some extent- that the person is taking a perspective in which the attention focus is not restricted to the transgression itself, but also on more positive (i.e., reinforcing) aspects of the relationship, leading to a wider and more realistic perspective of the relationship, which in turn may facilitate forgiveness (Fourie et al., 2020; Noor & Halabi, 2018; Worthington, 2006). On the other hand, resentment is negatively related to relationship maturation, and similarly, this could be due to the poor ability to take perspective on the event, the partner, and the couple itself, focusing only on the negative aspects of the event and probably ruminating about them.

Relationship deterioration was correlated negatively with forgiveness, and positively with resentment. In this factor, the person focuses on the negative aspects of the transgression carried out by the partner, probably in an attempt to prepare for future transgressions or the relationship breakup itself (Newman & Llera, 2011), with the idea that if it happens it will be less painful. However, this exercise could involve rumination processes and therefore amplify discomfort (Ciesla et al., 2011), and this may be the reason why the more this coping strategy is used, lower forgiveness and greater resentment levels will be present (c.f., de la Fuente-Anuncibay et al., 2021).

Problem-Focused Coping Strategies Scale

AFE on the P-FCS showed only the negotiation factor, on which both members of the dyad communicate and take action consequently in order to repair the damage done and prevent future incidents. Negotiation strategies may be considered as a combination of planning and active coping strategies measured by other scales (Carver et al., 1989), and even though there’s no previous scale that explicitly measures negotiation as coping, negotiation models can be better explained through the coping perspective (Schneider & Wilhelm Stanis, 2007).

Although negotiation can be really challenging for a relationship after a transgression, it turned out to be the strongest positive correlate of forgiveness. Negotiation involves contacting with the experience of unfair treatment (e.g., infidelity, lies, lack of respect, etc.), as well as with the aversive thoughts and emotions that this experience evokes (e.g., sadness, anger, disappointment, shame, etc.), however, it is essential to forgive (Enright & Fitzgibbons, 2015), and it also opens the possibility of resolving misunderstandings, as well as behavioral changes oriented towards taking care of the couple, which can allow the quality of the relationship to not only recover but to thrive (Hayes, 2020). Likewise, the results show a strong correlation between negotiation and the maturation of the relationship, so it is possible to assume that people who may have a broader perspective of the transgression also successfully negotiated effectively with their partners, which could lead to more positive interactions, and this, in turn, promote genuine forgiveness.

Conclusions

The measurement of the specific coping strategies carried out to deal with a transgression committed by the romantic partner allows us to account with major accuracy the psychological (dis)adjustment resulting from the transgression. Researchers who use this inventory may contribute to the identification of which coping strategies are adaptive or maladaptive, and to the understanding of the effects of each coping strategy on the transgression’s negative consequences on physical and mental health (e.g., Cano & O’Leary, 2000; Shrout & Weigel, 2018), and to their relationship’s quality (Schratter et al., 1998). Also, these scales may be useful in the development and testing of psychotherapeutic strategies to promote adaptive coping strategies.

Limitations and further Directions

Further construct validity work on the scales is needed. According to Dimitrov (2010), stability on factor structures from EFA (Rosales, 2018) to CFA, supports the structural aspect of the scales’ construct validity, while the correlations with forgiveness and resentment feed the external aspect of construct validity. Nevertheless, the substantive, generalizability, and consequential aspects of construct validity are still areas of opportunity. Therefore, we think that a useful next step in strengthening this inventory is to carry out invariance tests in other languages and cultures.

Given the cross-sectional and correlational nature of this research, it provides evidence of construct validity to the psychometric scales, but its scope is very limited when it comes to explaining the relationship between variables. Although possible explanations for the correlations found are outlined in the discussion, most of them require experimental designs to be strictly tested, so we believe it is necessary to carry out such research in the future, which in turn can contribute to the substantive aspect of construct validity. Finally, it is possible that integrating these measures as a single scale with two functional dimensions (i.e., avoidance and approximation strategies) might turn into a most parsimonious approximation to the phenomena. In the meanwhile, the E-FCS, M-FCS, and P-FCS might be useful, and their findings can be of great value in clinical practice.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)