Information and communication technologies have provided rapid social, cultural, and interpersonal changes (Amichai-Hamburger, 2002; McMillan & Morrison, 2006; Millan, Perez & Zamora, 2014). Those has been prioritized in adolescents and young people, due to the technologies’ being incorporated as a normal part of their development, socialization, and entertainment (Kuss & Griffiths, 2011; Young, 2008). In spite of the social and interpersonal changes that the communication technologies facilitates, the frequent use of these technologies has also been associated with other negative factors, such as the problematic use of technology (Cho et al., 2014; Jasso & Lopez, 2018; Kuss & Griffiths, 2011).

The fact is that, although technology is made to facilitate day-to-day activities for users, it can also complicate them (Beard & Wolf, 2001). The use of these technologies is considered to introduce new, less-controlled forms of communication, which is why some authors think an adaptation period to incorporate new attitudes and behaviors regarding their use is necessary (Sanchez-Carbonell, Beranuv, Castellana, Chamarro & Oberst, 2008).

One of the themes on which different studies have been performed is the problematic use of the Internet, also considered as an addictive behavior (Griffiths, 2005; Young, 1998). One of the most relevant models in Internet addiction studies is the one by Griffiths (2005), which mentions the addiction components model from a biopsychosocial perspective and defines it as a sum of traits of prominence, mood changes, tolerance, withdrawal symptoms, conflict, and relapses. These components are reflected both in the biological and psychosocial aspects, and all should be present to consider any type of behavior to be an addiction (Griffiths, 2005, 2013; Griffiths, Kuss & Demetrovics, 2014; Pezoa-Jares, Espinoza-Luna & Vasquez-Medina, 2012).

An addictive behavior toward the Internet is considered a present-day phenomenon of concern, where a number of psychopathological problems may manifest (Echeburua, 2012), and as an emerging public health problem (Chang et al., 2014). For example, college students have shown more exposure to Internet due to academic stress, a limited offer of pastimes, and maintaining social relationships online (Lee, 2015). Thus, social media consumption has been deeply implemented in the daily routine of students (Gomez, Roses & Farias, 2012).

Currently, social media represents the main use of the Internet. In relation to addictive behavior, addiction to social media is considered to be a subtype of Internet addiction (Błachnio, Przepiorka & Pantic, 2015). In recent years, a correlation has been found between this type of addiction and problems with social, interpersonal, family, and sentimental relationships, as well as performance issues (Escurra & Salas, 2014). Furthermore, it has a significant prevalence in being considered as globalized, as it affects everyone regardless of social stratus (Boubeta, Ferreiro, Salgado & Couto, 2015).

Nevertheless, it is important to differentiate between excessive usage and an addictive behavior. For instance, Turel and Serenko (2012) developed a model that explains the usage of social media, in which they differentiated being hooked (excessive use) from addiction, considering the former as a non-pathological behavior. Internet usage in itself does not pose a problem regarding addictive behavior, but rather a possible risk factor for addictive behavior, which leads to more complex aspects (Moreno, Jelenchick & Breland, 2015). In the same way, although the hours of use may be a risk factor towards addictive behavior, the excessive use did not correlate with psychopathological aspects such as depression, one of the main factors in addictive behavior (Jasso & Lopez, 2018). Therefore, studies found that reducing online time would not really prove effective for a clinical intervention, as it is not a significant contributor between depression and problematic Internet use (Moreno et al., 2015).

The truth is that the use of mobile devices has increased due to easy internet access, a factor that is important to consider as it incorporates elements related to addictive behavior toward the Internet and media (Mendoza, Baena & Baena, 2015). Furthermore, since mobile devices have Internet access through mobile data or a Wi-Fi connection, the usage time for social media has been increasing significantly due to its easy connectivity (Garcia, 2013). Therefore, the interest in addictive behavior toward social media has been increasing due to its current demand and influence on young people.

The term “technology addiction” has caused controversy among some researchers. In recent years, different terms have been used to describe this problematic behavior, describing it as compulsive use, dependency, pathological use, or addiction (Lam, 2014). Even today, debates still exist about whether it should be objectified as a disorder unrelated to substance addiction (Tonioni et al., 2012), and regarding its psychopathological meaning, but some symptoms prevail according to studies (Lam, 2014). Young (2010) mentions that the impact the Internet has is only beginning to be comprehended, since it is very complicated to estimate the scope of the issue, and its diagnosis is complex. Unlike substance dependency and abuse, the Internet offers many benefits to society and is not judged as addictive, besides being a necessary part of our personal and professional lives (Young, 2015).

Depression is one of the main factors with a correlation to addiction, as well as other negative aspects. The population group with higher probability to suffer depression are the young people, because of the physical, psychological, socio-cultural, and cognitive change processes that take place during the adolescent stage (Jasso & Lopez, 2018; Pardo, Sandoval & Umbarila, 2004), this might be one risk factor to develop an addiction behavior. Nevertheless, there is no consensus about whether depression is an effect or a cause of addiction.

Depression is characterized by two symptoms: anhedonia and a depressed mood (Błachnio et al., 2015). Previous research studies have identified psychological problems such as loneliness and depression as risk factors for addiction in general, especially internet addiction (Odaci & Kalkan, 2010; Özdemir, Kuzucu & Ak, 2014). The excessive use of internet could create a higher level of psychological stimulation, leading to few hours of sleep, fasting for long periods of time and limited physical activity, which could cause physical and mental health problems such as depression, loneliness, low self-esteem, and anxiety (Kim et al., 2006). In relation to social media addiction, it has been significantly associated with psychological symptoms, such as depression, stress, and anxiety (Meena, Soni, Jain & Paliwal, 2015).

For its part, Internet addiction and suicide are significant health issues for young people. Suicide is associated with other signs such as depression and emotional stress (Lin et al., 2014). According to the interpersonal perspective of suicide, a depressed person may feel like a burden for others and feel disconnected from social groups, social isolation being a common characteristic. They may have a negative view of themselves and experience interpersonal problems and, therefore, feel an increase in the negative beliefs of burden and belonging which are associated with the increase of suicidal ideation (Kleiman, Liu & Riskind, 2014). In Mexico, suicide shows a clear upward trend, with university students between the ages of 18 and 25 having reported a higher increase in suicidal behavior, mainly consisting of suicidal ideation (Cordova & Rosales, 2016).

Suicidal ideation is understood as all thoughts regarding wishing and planning to take one’s own life by suicide, without having made an evident attempt, which occupy a significant place in the individual’s life (Rosales Cordova & Ramos, 2013). A correlation has been found between depressive symptoms and the problematic use of Internet, suicidal ideation being a factor related to the risk of problematic use of the Internet (Moreno, Jelenchick & Breland, 2015). Even though there is a relation between suicidal ideation and addictive behavior toward social media (Lin et al., 2014), it is not a direct predictive factor, but could be a protective factor when related to depression, with the addictive behavior as an escape and a search for support, due to the characteristics of social media (Jasso & Lopez, 2018). Another factor that could be related is impulsivity, as it is a shared characteristic of suicidal ideation and problematic use of the Internet (Aboujaoude, 2016).

Cybervictimization tends to be reported more frequently with internet use, and it has even been related to the problematic use of and addiction to the web (Yun-Kyoung & Jae-Woong, 2016). Teenagers that spend more time online are exposed to potential risks, including the risks of harassment, bullying, invasion of online privacy, identity theft, and sexual grooming or exploitation (Gamez-Guadix et al., 2013). Diverse studies have associated cybervictimization with depression (Gamez-Guadix et al., 2013; Hinduja & Patchin, 2010; Jasso, Lopez & Gamez-Guadix, 2018; Kowalski et al., 2014), which, in turn, as has been mentioned, can lead to a higher risk of suicide among young people (Hinduja & Patchin, 2010). Furthermore, cyberbullying has been found to be an important factor related to suicidal ideation, which means the victims have a high risk factor of manifesting suicidal thoughts and behaviors, as well as committing suicide (Hinduja & Patchin, 2010; Jasso, Lopez & Gamez-Guadix, 2018; Kowalski et al., 2014).

Within the individual factors, victims who suffer aggression often demonstrate negative emotional states such as anxiety, low self-esteem, depressive behaviors, suicidal thoughts, loneliness, frustration, irritability, somatization, sleep disorders, and high levels of permanent stress, among others (Bartrina, 2014). Cybervictimization contributes significantly to suicidal ideation, depression, and anxiety over time of cyberharassment, suggesting bidirectional relations between them, or reciprocal relations (Wright, 2016).

On the other hand, internet addiction has also been associated with the increase of cyberbullying problems, sleep deprivation and perturbation issues, aggression and personality problems, among other factors, which can cause mental, physical, and social damage (Weinstein, Feder, Rosenberg & Dannon, 2014). Cybervictimization has been found to predict an increase in the problematic use of the Internet in relation to those who are not victims. Nevertheless, problematic use does not predict cybervictimization, which is why some authors conclude that victims use the internet to escape from or avoid harassment anxiety (Gamez-Guadix et al., 2013; Leung & Lee, 2012).

Cyberbullying, as well as depression, alcohol consumption, and the problematic use of internet are important health problems that increased notably during adolescence, making it a critical moment to begin prevention and intervention (Gamez-Guadix et al., 2013). Also, depression is a prominent predictor of suicidal behavior, manifesting mainly in ideas, threats, attempts, or completed suicide (Duarte et al., 2012; Stewart et al., 2015; Tuisku et al., 2014).

Although in recent years the study and prevention of cybervictimization has been prioritized, it remains a significant problem among young people. According to Wright (2016), most of the attention to cyberbullying victimization has focused on children and adolescents, paying little attention to college students. Not recognizing this population’s vulnerability could increase the risk of negative socioemotional results. Tools available on the Internet, such as social media, facilitate the propagation of cyberharassment through mistreatment, ridicule, threats, blackmail, and discrimination, among others, many of these being performed anonymously to keep the identity of the assailant unknown (Lopez, 2016). Furthermore, the impact of social media shows us interesting aspects regarding the handling of victimization. Nevertheless, the debates over the terms of technological addictions, although the subject is of great interest, cause the ongoing controversy and confusion about the study of this phenomenon. As it is still not recognized as a disorder by the DSM-5 and there is no absence of diagnostic criteria, diverse terms exist to explain one problematic conduct, as well as others that could be confused between pathological and non-pathological behavior (Jasso & Lopez, 2018; Laconi, Tricard & Chabrol, 2015; Lam, 2014; Rial et al., 2015). Therefore, it is important to focus research on these subjects, since, despite the years that have been dedicated to studying this phenomenon, the impact and scope of the problem is only beginning to be comprehended (Young, 2010, 2015). Thus, the objective of this study is to analyze the relationship between addictive behavior toward social media, cybervictimization, depression, and suicidal ideation, and to propose an explanatory model which measures the association between these variables.

Method

Participants

The sample was composed of 406 college students. A non-probabilistic sampling was utilized by quota for scale application: 54% are female and 46% are male, being statistically equivalent (binomial test: p=.12). The mean age is 20.09 (SD=1.92) in a sample with an age range between 18 and 24 years of age.

Instruments

Social Media Addiction Questionnaire (Cuestionario de Adicción a Redes Sociales, SMA) by Escurra and Salas (2014). The questionnaire is a scale consisting of 24 Likert-type items with a 5-point scale (from 1 equals “never” to 5 equals “always”). This instrument is designed to evaluate social media addiction in college students. It includes terms such as “I feel a great need to stay connected to social media” and “I feel anxious when I cannot connect to social media.” The scale’s total internal consistency is α=.94, hence considered reliable for having excellent consistency. The majority of the items have the same direction, except for item 13 “I am able to disconnect from social media for several days,” which was inverted so all items could be measured in the same direction and have a total score.

Cyberbullying-Victimization Questionnaire (Cuestionario de Cyberbullying-victimización, CBQ-V) by Estevez, Villardon, Calvete, Padilla & Orue (2010) is a questionnaire which consists of 11 items describing different affirmations that identify the way people suffer cyberharassment, reporting the frequency at which they have suffered such aggression. The scale is Likert-type with a 3-point range (from “1” equals “never” to “3” equals “often”), and includes items such as “Writing jokes, rumors, gossip, or comments on the internet which ridiculed me” and “Intentionally staying away from an online group.” The Cronbach alpha coefficient is α=.93, which reflects excellent reliability.

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) in its short version consisting of 10 items, originally created by Radloff (1977) and revised by Eaton et al. (2004). This scale consists of 10 Likert-type items with a 5-point range (from “1” equals “never” to “5” equals “always”) which measures emotions and situations related to depression that the individual may have felt in the previous two weeks. It includes items such as “I felt sad” and “I could not keep moving forward.” The scale’s consistency for this present study was α=.91, which is considered a reliable scale.

Positive and Negative Suicidal Ideation Inventory (PANSI) by Osman, Gutierrez, Kopper, Barrios y Chiros (1998). This is a 14-item questionnaire, six of which measure positive suicidal ideation (protective factors) and eight which measure negative suicidal ideation (risk factors). It employs a Likert-type scale with a 5-point range, from “1” equals “never” to “5” equals “always.” The items are evaluated in the timeframe of the previous two weeks and ask how often each of the 14 thoughts presented themselves. It includes items such as “Have you seriously considered killing yourself because you couldn’t live up to others’ expectations of you?” and “Did you think about killing yourself because you couldn’t find a solution to a personal problem?” The internal consistency of the positive suicidal ideation dimension was α=.96, which is considered excellent reliability.

Procedure

The study used a transversal ex post facto design. The type of study was explanatory through the modeling of structural equations based on the variables of social media addictive behavior, cybervictimization, depression, and suicidal ideation. Young people were invited to participate in the poll with the prior authorization by their universities. The questionnaire was administered through an online platform. Before participants answered the survey, the study’s general objectives were explained. The platform was shown to the participants and they received instructions on how to access and answer the survey. The first page focused on informed consent, allowing the participants to accept or reject answering the survey. After participants agreed, they could begin answering the questions. Participants had to answer all questions before completing the survey; therefore, there were no missing points. Confidentiality and anonymity were guaranteed. The study was approved by the academic committee.

Data Analysis

On a first instance, each of the variables was totaled through addition and average of the scale’s items. After revision of the analysis of normality adjustment and descriptive data of the sample, the correlation coefficient statistical test was used to analyze the relationship between the variables of interest. Finally, through relationship analysis, an explanatory model was designed in the statistical software AMOS, in which the analysis was performed through a modeling of structural equations.

Results

First, the sample characteristics with respect to the use of social media were analyzed. WhatsApp was reported as the most-used social network (54.2%) followed by Facebook (35.5%). Regarding the main use of social media, the results showed contact with friends (36.2%), entertainment (16.7%), contact with a significant other (13.1%), and contact with schoolmates and/or coworkers (9.6%). It was reported showed that the young people use social media for around seven hours daily (SD=4.68) and that the age at which they began using social networks was around 13 years old (SD=2.13). They reported that they use social media more often in their home or place of rest, with mobile devices being most frequently utilized (M=4.44, SD=.747).

A reliability and normality analysis was performed on the scales. Results reported an internal consistency that went from good to excellent for the total scores and scale dimensions (α=91-96). The respective descriptive analyses were performed, showing social media addiction with the highest mean. The lowest mean was reported for cybervictimization (see Table 1). After the sum of the dimensions and their respective total scores, a normality analysis was performed to see the respective normality distribution, reporting that the results did not adjust to a normal curve through the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

Table 1 Descriptive statistics, reliability, and normality

| Reliability | Descriptive Statistics | Normality | |||||||

| Items | α | M | Mdn | S.D. | S | C | Z K-S | p | |

| SMA | 24 | .94 | 2.38 | 2.29 | .74 | 0.44 | -0.31 | .059 | <.01 |

| CV | 11 | .93 | 1.17 | 1.00 | .36 | 2.74 | 7.80 | .331 | <.01 |

| Depression | 10 | .91 | 1.96 | 1.80 | .87 | 1.12 | 0.69 | .135 | <.01 |

| Suicidal Id. | 8 | .96 | 1.51 | 1.00 | .93 | 1.91 | 2.65 | .329 | <.01 |

Note: N= 406. SMA = Social Media Addiction; CV = Cybervictimization; Range: SMA = 1-5; Cybervictimization = 1-3; Depression = 1-5; Suicidal Ideation = 1-5.

Secondly, the correlation between study variables was analyzed through the Spearman’s Rho non-parametric test. All study variables reported a positive and significant correlation, oscillating between a low and medium correlation. The highest correlations were found between depression and suicidal ideation (rs=.48, p<.01) and between cybervictimization and suicidal ideation (rs=.37, p<.01) (see Table 2).

Table 2 Correlation Matrix (Spearman’s Rho)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 1. SMA | 1 | |||

| 2. Cybervictimization | .14** | 1 | ||

| 3. Depression | .25** | .32** | 1 | |

| 4. Suicidal Ideation | .18** | .37** | .48** | 1 |

Note: Significance levels: *p<.05; **p<.01

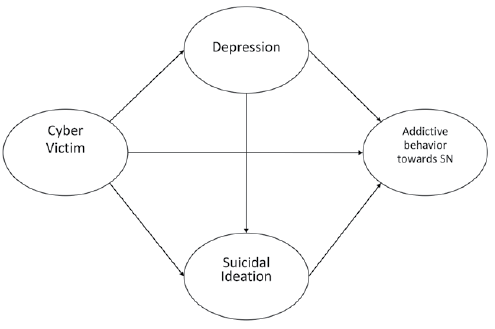

Following the correlation analysis, the hypothetical model was analyzed through the modeling of structural equations. The model postulates that cybervictimization increases the probability of depression and suicidal ideation. In turn, the increase in online victimization is associated with a higher addictive behavior toward social media. This model postulates several mediated relationships. The relationship between cybervictimization and suicidal ideation could be mediated by the presence of depression, while the relationship between cybervictimization and addictive behavior toward social media is mediated by depressive symptoms and/or depression. This hypothetical model is presented in Figure 1.

Figure1 Hypothetical model of direct and indirect relationships between addictive behavior toward social networks (media), cybervictimization, depression, and suicidal ideation.

With the objective of proving the model’s theoretical fit, an analysis was performed using the maximum plausibility method. In order to carry out the model’s fit by way of this analysis, the analysis was performed supported by a simulation of “bootstrap” sampling. This way, the analysis was fitted to a normal distribution to calculate standard errors and create confidence intervals (Changya & Yu-Hsuan, 2010). Goodness of fit was evaluated using the non-normalized fit index (NNFI), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) standard. NFI and CFI values of 0.90 or higher indicate a good fit. RMSEA values under .08 indicate a suitable fit (Byrne, 2006).

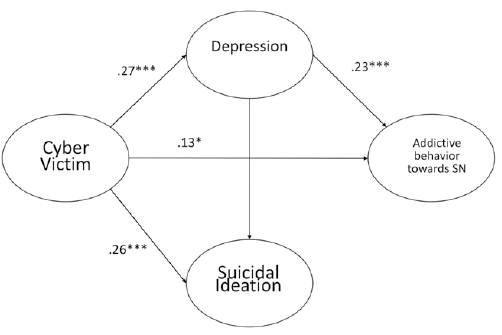

An analysis of the hypothetical model was carried out; however, when finding that suicidal ideation did not significantly explain addictive behavior toward social media, the correlation was eliminated, for which reason analysis of the fitted model was performed. Analysis of the model was performed by way of three-element plots. Each item was randomly assigned to one of the plots (Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, 2002). The fit of the fitted model was adequate: χ2 [49, N = 406] = 135.06, p >.001 y χ2/gl = 2.76; NFI = .96, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .066. As can be seen in Figure 2, cybervictimization explains the probability of depression [β=.27, p <.001], which in turn explains the probability of reporting suicidal ideation [β=.26, p <.001]. Additionally, depression considerably explains the probability of suicidal ideation [β=.52, p <.001]. Finally, both cybervictimization and depression directly explain the probability of an addictive behavior toward social media [β=.13, p <.05 y β=.23, p <.001, respectively]. Once the model was revised, the power of the model was analyzed. The model explained 7% of the variance of depression, and 41% of suicidal ideation and 8% of addictive behavior toward social media (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Explanatory structural model of addictive behavior toward social networks (media), cybervictimization, depression, and suicidal ideation.

The model also suggests the presence of several indirect correlations between variables. The size of the mediated effects and their significance levels were analyzed. The Sobel test was used to determine the statistical significance of the mediated effects. Data supported the following indirect correlations: An indirect correlation between cybervictimization and addictive behavior toward social media, mediated by depression (.06, p <.01); and an indirect correlation between cybervictimization and suicidal ideation, mediated by depression and addictive behavior towards social networks (.14, p <.01). No indirect correlation was reported between the other variables in the model.

Discussion

Firstly, it was found that the social networks most utilized by young people were WhatsApp and Facebook. This coincides with the popularity that Facebook and WhatsApp have as being reported by Mexican internet users to be the most popular social networks in Mexico, followed by YouTube, Twitter, and Instagram (Mexican Internet Association, 2017). Furthermore, Facebook is considered to be one of the most important social networks among college students in Mexico (Dominguez & Lopez, 2015). The main reported uses by young people were keeping in touch with their friends, significant others, and co-workers, besides entertainment: some of the most important characteristics of social networks usage in general. The young people reported using social networks for about 7 hours per day. According to the Mexican Internet Association (2017), Mexican internet users use social networks for 2 hours and 58 minutes, representing 38% of the time connected to the Internet (8 hours and 1 minute). In this case, we must consider that the internet user population was measured in general; while a great part of social media users are young people. The age at which they began using social media was 13 years old. 72% of Mexican internet users report being an internet user for over 8 years and 21% of them for 3 to 8 years (Mexican Internet Association, 2017). Mobile devices are the most widely reported means of access to social networks, without precluding the fact that they also use computers, although less frequently. Currently, 90% of Mexican internet users are mobile device users; thus, mobile devices are considered to be the most popular means of access (Mexican Internet Association, 2017). The places where social media was reportedly accessed most were the young people’s homes, followed by school and/or workplace.

A significant relation was found between the study’s variables. The highest correlations were reported in suicidal ideation with depression and cybervictimization. These variables have been frequently analyzed and a relation between them has been found (Gamez-Guadix et al., 2013; Hinduja & Patchin, 2008, 2010; Kowalski et al., 2014). A significant correlation was also found linking addictive behavior toward social media with cybervictimization and suicidal ideation. Some authors have found that addictive behavior toward internet and social networks could be considered an act of evasion to escape negative thoughts and emotions (Gamez-Guadix et al., 2013; Leung & Lee, 2012; Parra et al., 2016), even finding a means for emotional support (Bousoño et al., 2017; Daine et al., 2013). In relation to depression and addictive behavior toward social media, a significant correlation was found. The relationship was expected and coincides with a great variety of studies, since it is considered one of the psychopathological disorders most highly related to addictions and one of the most important ones to evaluate when talking about addictions (Gonzalez-Gonzalez et al., 2012; Medina-Mora & Berenzon, 2013), including technological addictions (Dalbudak et al., 2014; Gamez-Guadix et al., 2013; Ho et al., 2014; Orsal et al., 2013; Sahin et al., 2013).

After the proposal of the hypothetical model, a correlation between cybervictimization, depression, suicidal ideation, and addictive behavior was expected to be found. Suicidal ideation was not explained by addictive behavior toward social media. Although some studies have found a correlation between the former and the latter (Aboujaoude, 2016; Lin et al., 2014), it would seem as though this correlation may be mediated by other factors. The goodness of fit improved a bit when the non-significant correlation was eliminated. Finally, the revised model proposes that cybervictimization leads to depression, suicidal ideation and, to a lesser degree, addictive behavior. In turn, depression may lead in two directions: addictive behavior and suicidal ideation. Suicidal ideation is independent of addictive behavior toward social media, mediated by depression. The model explains 41% of suicidal ideation, while addictive behavior has a lower explanation of 8%. This could indicate some limiting factors in the model. Although the inadequate use of Internet is regularly associated with a higher risk to negative effects, positive aspects could also be found which have not been analyzed in the model. For instance, the Internet has been associated with being a means for social support or for escaping negative thoughts (Daine et al., 2013; Gamez-Guadix et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2006; Leung & Lee, 2012; Parra et al., 2016). Cybervictimization and depression have been associated more with suicidal ideation than with addictive behavior toward social media, so we were also expecting a greater explanation for suicidal ideation.

Nowadays, our reality is immersed in the use of technology. Internet use is an important part of many aspects of everyday life, such as sexuality, education, and socialization in general (Jasso, Lopez & Gamez-Guadix, 2018). Due to the connectivity and interactivity of new technologies, their popularity continues to increase and, therefore, they are indispensable. Thus, in direct and indirect ways, technology is influencing society. However, technology is also being influenced by culture. Although virtual culture is also mentioned (Jones, 1997), it is also influenced by traditional culture. Recent studies have found how social networks can serve as a space of freedom, but attitudes are still influenced by cultural values (Al Omoush, Yaseen & Alma’aitah, 2012; Vasalou, Joinson & Courvosier, 2010; Waters & Lo, 2012).

In other words, culture is also submerged in technology, adapting part of traditional culture to online interaction within a virtual culture. Culture determines the foundation, structure, and acceptable and desirable codes of conduct (Diaz-Loving, 2006). For instance, in reference to Mexican culture, intercultural exchange has been reported to have surpassed cyberspace limits, so that cultural manifestations develop simultaneously as Mexican and global (Coronado & Hodge, 2001). Therefore, virtual culture is also being influenced by sociocultural aspects, which refer to the system of thought and ideas that gives hierarchical structure to interpersonal relationships and stipulates premises, such as standards and roles, for individual interaction. These aspects influence behavior and serve as a guide within families, groups, society, and institutions (Diaz-Guerrero & Peck, 1963; Diaz-Loving, 2006), such as cybersociety.

In conclusion, the sample reported some characteristics of addictive behavior. This could be a warning sign of vulnerability in young people. Depressive symptoms showed the highest correlation to addictive behavior toward social media, coinciding with the study of addictions in general. The final model explains that cybervictimization could lead to depression, followed by suicidal ideation. However, depression could also lead to addictive behavior toward social media. Suicidal ideation doesn’t explain addictive behavior, which is why they could be considered as different consequences of cybervictimization and depression. The study had some limitations, which is why it is important to continue researching and deepening the explanatory models, carrying out studies with qualitative and mixed focuses, as well as forming proposals for prevention and intervention programs.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)