|

Summary: I. Introduction. II. Methods. III. Classification of cases. IV. Justification. V. Conclusion. VI. Bibliography. |

I. Introduction

In Mexico, during most of the 20th century, the political system was dominated by the political party known as PRI (Partido Revolucionario Institucional). Political scientists, such as Giovanni Sartori (1980), considered PRI's authoritarian rule as a hegemonic party regime (p. 281). For most academics, the Mexican democratic transition took place just a few decades ago and ended as recently as in the 1990's (Woldenberg, 2013, p. 15). Considering that such a vertical regime lacked of real checks and balances, one can easily find that the Mexican Supreme Court was not a central political actor

The purpose of this paper is to study the role of the Supreme Court in the Mexican political system during the years democratic transition. The research question is whether or not the Supreme Court has contributed to the democratization of the Mexican political system throughout those years. The literature on the Mexican democratic transition has usually been focused on the historic processes of building electoral institutions (see Woldenberg, 2013, for more detail). Instead, it has been mostly in the United States where the judiciaries have been prolifically examined as political actors. This paper is, in that context, in line with the studies carried out from political science, known as "judicial politics", which analyze the role of the judiciary in authoritarian and democratic regimes. The academic works of Schubert (1965), Pritchett (2014), Murphy (1973), Epstein and Knight (1998) constitute classic examples of that effort that started almost 80 years ago. In Latin America, judicial politics has held an increasing interest in recent years among authors such as Hilbink (2014), Ansolabehere (2007) and Ríos (2004). Nevertheless, my perspective is significantly different since I introduce a legal philosophy approach.

I consider that there is a correlation not only between the judiciary and democracy, as O'Donnell (2004) and many other political scientists have stated, but also between democracy and theories of law. Ronald Dworkin (2006) has demonstrated that there is a correlation between philosophical theories of law and the way judges adjudicate. Sartori (2008) has asserted that theories of law have an impact on democracy (p. 202).

My central argument is that if judges adjudicate based on theories of law, and if these can affect democracy, therefore, courts' sentences and their philosophical core may affect democracy. I claim that the Supreme Court, through adjudication, has contributed to the democratization of the Mexican political system. Some researchers may find this perspective too evident considering the role of the judiciary in liberal democracies, even Tocqueville (2000, p. 106) pointed that out nearly 200 hundred years ago. However, I will elaborate further: if Dworkin and Sartori are correct, my hypothesis is that, in the development of the democratic transition, the Mexican Supreme Court experienced a distancing from legal positivism and it approached to natural law. I will attempt to prove this by referring to the fact that -in the short history of Mexican democracy- most of the relevant cases adjudicated by the Supreme Court introduced new forms of legal interpretation that are in accordance with natural law.

I understand legal philosophy, as philosophy in general, as a reflective activity on the nature of beings, in this case, as a reflection on what law is. It comprehends a large range of subjects; among them -as we will see- the connection between the definition and the validity of law. The main focus of this paper is to explain how legal philosophy categories (theories of law) interact with democratic ones (political science theories) in specific cases adjudicated by judges. I believe the explanation of that interaction is possible due to concepts that emerge from both legal positivism (such as subjectivism, territorialism, normativism and formalism) and natural law (objectivism, universalism, principlism and liberalism).

One last aspect of my argument links interpretation (specifically that one close to natural law and employed by constitutional courts) with democracy. This correlation would confirm my hypothesis:

— The closer the mentalities of judges are to natural law, the more they will prefer methods of interpretation used by constitutional courts. These methods are based on notions in which natural law has been developed (such as morality, moral objectivity, values, universality, principles and human rights).

— The more the Supreme Court adjudicates as a constitutional court, the more its contribution to Mexican democracy will be.

Some or many of these affirmations might seem obvious to a reader coming from a country with a common law tradition. Nevertheless, it is not that obvious in Mexico. Our legal system had been historically positivist, and the Supreme Court had been part that tradition.

As Jorge Esquirol (2011) says, in Latin America there has been a turn towards a new interpretation in opposition to the "aberrant" formalist thought (p. 1034). This interpretivism has an European and North American liberal background that has fueled a more progressive discussion of constitutional law due to a greater contact with foreign theorists and students educated abroad. However, Esquirol is also skeptical of the automatic benefits of this transplantation of ideas. I believe that the final balance of this criticism of legal positivism will be favorable for the judicialization of human rights.

I once received a positivist education in law school and normalized it: there were no "human rights"; rights were to be created by authorities and, therefore, were not inherent. But during the last three decades a new mentality have been introduced and it will have an impact on how we interpret the law. We now assume that not only law and morality are connected, but also that the first one derives from the latter; we accept, therefore, the existence of values and principles in law, as well as the existence of human rights; and that implies notions of universality and moral objectivity.

To demonstrate the correlation between theories of law and democracy, I analyzed 9 relevant cases (adjudicated by the Supreme Court between 1995 and 2011) and conducted 14 in-depth interviews to chief justices, researchers and politicians. This paper presents some results of a broader research. For that reason, I will only focus on the cases. As to the interviews, being that they assure the recollection of considerable information, I would prefer to present its analysis in a more extensive publication. The ground for that decision lays on a theoretical motivation. I believe that the philosophical theories of law are authentic legal ideas and I consider that their value as such should be vindicated. I have decided to approach these legal concepts in the light of the figurational sociology of Norbert Elias (2012) (who, it seems to me, is not known well enough in Mexico among legal researchers). In that sense, I argue that legal ideas (manifested as legal positivism and natural law) are figurations: forms of interdependence among human beings and, therefore, different ways of understanding, in this case, the law. This -as I see it- has an impact on how judges interpret the law. I claim that it is possible to offer a better description of the correlation between theories of law and democracy if we realize that legal positivism and natural law are but figurations.

The interviews offer abundant and fascinating information. Most of it comes from the chief justices themselves. They do not only express the way they conceive the law (which might be my main interest here), but also reveal critical facts about how they work. Since in Mexico justices do not deliberate in public, the interviews provide unprecedented information and confirm some other speculations on how they deliberate, how they conciliate and "exchange" their votes among them, and how they face political pressure to alter their decisions. But as I said before, I will deliver that analysis in a broader publication.

For this research, I relied on methods of qualitative analysis: 1) in-depth interviews; 2) documentary analysis, and; 3) interpretation criteria. The interviews were useful not only to reconstruct the role of the Supreme Court during the process of democratic transition, but also to ameliorate the selection of cases. Once selected, I analyzed the Supreme Court sentences and interpreted them based upon pre-established criteria.

II. Methods

The selection of cases was determined by four criteria. Each Supreme Court sentence was chosen if it contributed to democracy, and it was considered as such when it gave rise to: 1) public debate, 2) political participation, 3) transparency, and 3) rule of law.

In Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition, Robert A. Dahl (2013) studies what conditions favor or impede the transformation of one regime into another, specifically from an authoritarian to a democratic regime. It is remarkable -at least from the Mexican political system's point of view- how Dahl does not focus his analysis on electoral institutions or electoral procedures. Instead, he examines other aspects that one might not initially consider important. Dahl's thesis basically holds that public debate and participation are the two dimensions that determine the transformation of an authoritarian regime into a democratic one. Democracies (polyarchies) are systems that are both "substantially liberalized and popularized" (Dahl, 2013, p. 17), that is, they are very representative and at the same time very open to public debate. For instance, in the Soviet Union, there was a formal participation (elections) but no real public debate. On the other hand, in the 18th century British political system, although there was plenty of public debate, political participation was extremely reduced (p. 16).

In addition to Dahl, I also consider the contributions of other authors related to democratic theory and political transitions, such as O'Donnell (2004), Morlino (2008) and Diamond (2005). From them, I identified transparency and rule of law as the two last criteria that turn a political regime into a democratic one. Therefore, the Supreme Court will contribute to democracy, as I said, when it increases: 1) public debate; 2) participation; 3) transparency; and 3) rule of law.

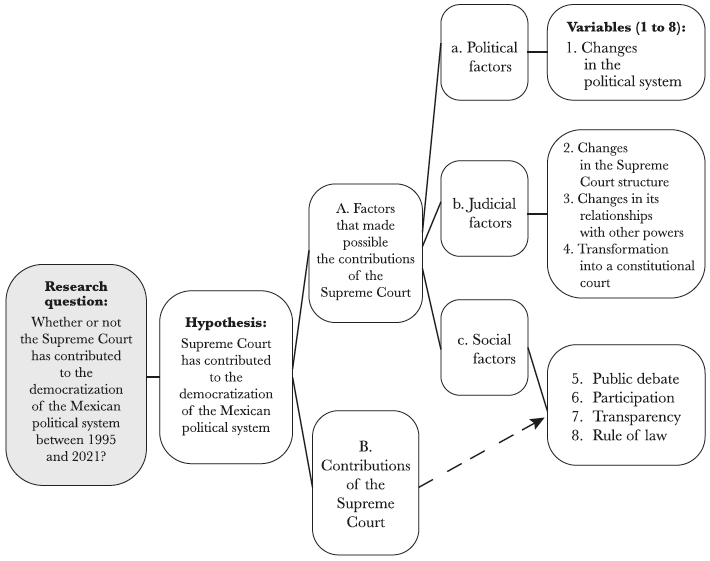

Now I will describe how these criteria fit in the set of variables I constructed. In this research, I differentiate between: A) the factors that made possible the contributions of the Supreme Court, and B) the actual contributions of the Supreme Court.

Regarding the factors (A), two points should be considered: the internal aspects of the Supreme Court (the judiciary itself) and the external aspects (related to the political system and the social system). Therefore, I classified these elements into: political (a), judicial (b) and social (c) factors.

The first factor, the political one (a), deals with the changes in the Mexican political system (variable 1), and I would like to emphasize the year of 1994 as a crucial moment for our transition to democracy.

As for the internal factor, the judicial one (b), I refer to: the changes -also in 1994- in the structure of the Supreme Court (variable 2); the changes of relation with other powers (variable 3); and the transformation of the Supreme Court into a constitutional court (variable 4).

The third factor, the social one (c), deals with the changes in Mexican society in terms of the criteria already mentioned (democratizing dimensions). That is, Mexican society claimed and, therefore, experienced an enhancement of public debate (variable 5), participation (variable 6), transparency (variable 7) and rule of law (variable 8).

I believe all these variables must be taken into account to describe role of the Supreme Court during the political transition. Since the democratizing dimensions correspond to the variables 5 to 8, the selection of cases that have contributed to Mexican transition has been made based on such criteria.

All the above can be summarized as follows:

1. Changes in the political system (variable 1)

The year of 1994 was crucial for the democratic transition. The authoritarian regime was experiencing a process of deterioration. That year Mexico faced an economic and political crisis that forced changes in the political system in order to provide stability. Academic consensus, led by Woldenberg (2013), asserts that Mexico's transition to democracy took place between 1977 and 1997 (p. 15). Nevertheless, I find Alonso Lujambio's (2000) thesis more accurate: he places the Mexican democratic transition later (mostly during the 1990's) and he offers an empirical basis for that claim (pp. 14 and 15). Lujambio demonstrates that despite losing the House of Representatives in 1994, the ruling party (PRI) still held, by 1999, a hemegonic power (e. g., in the Senate, state governors and state legislatures).

I support Lujambio's thesis and I believe that democratic transition took place in Mexico slightly later (during the 1990's). It is not a coincidence that the manifestations of such transformation became visible in the judicial branch at that same time. There would be a causal relationship: the Supreme Court was forced to change because the political system was already on a process of reformation.

The Mexican judiciary went through a profound transformation between 1994 and 2011. In other words, if there was, in time, a correlate between the changes in the Supreme Court and Mexico's transition to democracy, it would be that same period.

In Mexico, judiciary's work has been historically divided in periods. The period between 1995 and 2011 is known as the Ninth Period of the Federal Judiciary in which the Supreme Court was drastically modified. The selection of cases was, therefore, limited to those adjudicated between 1995 and 2011: the years of political transition in Mexico.

2. Changes in the judiciary (variable 2, 3 and 4)

These changes in the political system allowed to model a different structure and new powers for the Supreme Court. For instance, the integration, the number and the designation of justices was altered (even the justices in service by 1994 were dismissed). I will focus, however, on the new powers granted to the Supreme Court. Such prerogatives derived from a constitutional reform that was passed in December 1994 and it implied a new balance of powers and, consequently, different forms of relationship among the branches of government. The Supreme Court went from having a secondary role in the Mexican political system to being a central political actor vis-à-vis the legislative and -more importantly- the executive power.

This transformation towards an horizontal accountability was possible because the Supreme Court became an authentic constitutional court. Its powers related to judicial review were strengthened. In Mexico, there was already a mechanism of judicial review, known as amparo, in hands of citizens to prevent violations of rights acknowledged in the constitution. However, the 1994 constitutional reform created a new mechanism, known as acción de inconstitucionalidad, and revitalized another one called controversia constituional (which was a dead letter by then). Both are in hands of state actors and they allow executive and legislative actions to be subjected to review by the Supreme Court. By those means, judicial review and horizontal accountability were strengthened in Mexico.

I believe that the Supreme Court was not part of the actors that triggered the democratic transition. On the contrary, I point out that the democratic transition was the one that provoked the transformation of the Supreme Court. Only then, the Supreme Court, already installed in its new role as constitutional court, would be able to support and stimulate the democratic transition.

3. Changes in the Mexican society (variable 5, 6, 7 and 8)

The new structure of the Supreme Court and its consequences in the democratic dynamics among political actors would apparently confirm the validity of the institutionalist theory. This theory holds that the redesign of institutions can carry out changes in social and political interactions. Thus, the structures, norms and powers given to an institution determine the behavior of individuals (Scott, 2004). This might be true, but only in appearance: I will not deny the importance of modifying norms and institutional structures, however, that does not necessarily translate into social transformations. I would say it is the other way around: the redesign of the Supreme Court was possible because the Mexican society had already changed and it demanded those political and legal adjustments.

For Norbert Elias (2012), one fundamental task of social scientists is to explain social transformations. A common mistake, as Elias argues, is to study such transformations through the isolated analysis of institutions. This does not mean that the analysis of institutions, norms or individuals is irrelevant. However, "the mental habit of asking about the specific authors of social transformations or, in any case, of facing these transformations looking only at legal institutions" makes impossible its understanding, Norbert Elias says (p. 339). And he adds: "in all cases what we see are the results of the actions of isolated individuals and what is presented to us are their personal weaknesses and gifts. There is no doubt that this method is fruitful, and it is essential to consider history under this dimension, as a mosaic of singular actions driven by isolated individuals", but that is -he claims- insufficient (p. 313).

Elias (2012) states that societies are the product of the values, feelings and mentalities shared by the individuals of a community. Therefore, political, legal or social transformations reflect a change in the networks of conceptions (figurations) about the ways of living, feeling and thinking shared (pp. 29-33). In other words, the Mexican political system changed because our society had modified its mentality, emotions and values. It demanded more public debate, political participation, transparency and rule of law.

When, in a regime, at least some members of the political system can oppose the government and some of their rights are guaranteed, then public debate is produced. Regimes, Dahl (2013) says, vary substantially (from authoritarianism to democracy) in the extent to which they offer such guarantees to opponents, and therefore vary as much as they tolerate opposition and facilitate public debate (p. 14).

However, public debate is not enough. Regimes also vary in the number of people that participate in public affairs. Participating, Dahl (2013) says, is "having a voice in a public debate system" and participation also implies representativeness: "the greater the number of people who enjoy this right, the more representative the regime will be" (p. 15).

In relation to transparency, it implies not only access to information for public debate, but also openness in decision-making and it is a tool of good practices in the execution of public policies, in a way that allows for accountability, efficiency and effectiveness (Ball, 2009, p. 293). Joseph Stiglitz (1999) has stressed that transparency is crucial in the informed participation of citizens for decision-making, and has warned of the risks posed by governmental secrecy. Therefore, it becomes essential for the democratization of political systems and the development of the rule of law.

In terms of the quality of democratic regimes, the rule of law is one of the essential pillars, as O'Donnell (2004) states, on which a true democracy rests. O'Donnell emphasizes two elements of the rule of law: the role of independent judiciaries and the equal treatment that the rule of law must guarantee in favor of citizens (p. 32). Therefore, the rule of law can be understood as the state constrained by law. For O'Donnell, this expression refers to the consistent application of laws by the judicial or administrative authorities, regardless of the class, status or power held by the parties involved (p. 33).

Consequently, each time judges adjudicate protecting individual liberty, they also constrain the power of the State and, therefore, improve the rule of law. And each time judges preserve equality, they contribute to the equal treatment that the rule of law presupposes. From this conception, it follows that the rule of law is strengthened when liberty and equality are defended.

In-depth interviews

The cases adjudicated by the Supreme Court that were subjected to analysis, were only those that promoted one or more of the four democratic dimensions already mentioned. I first made a list of cases based on the specialized literature. That selection was not definitive, since it was later contrasted with the cases discussed during the in-depth interviews.

The purpose of the interviews was to reconstruct the process of democratic transition in Mexico and the role of the Supreme Court in that moment. The standards to choose the interviewees were: a) men and women; b) old and young, that; c) by their testimony or by their renewed vision, that is, by experience (because they were actors of the transition) or by knowledge (because they were specialized in the subject), could reconstruct such process; d) from different perspectives: academia, politics and administration of justice. The interviewees were a total of 14 people (in alphabetical order): Karina Ansolabehere,1 José Antonio Caballero,2 Jaime Fernando Cárdenas Gracia,3 Héctor Fix Fierro,4 Fernando Gómez Mont,5 Mara Gómez Pérez,6 chief justice Genaro Góngora Pimentel,7 chief justice Guillermo Ortiz Mayagoitia,8 Ricardo Pozas Horcasitas,9 Pedro Salazar,10 chief justice Juan Silva Meza,11 Francisco Tortolero,12 justice Diego Valadés13 and José Woldenberg.14

Throughout this research, a total of 46 cases were mentioned. Of these, 43 were specified by the interviewees; the other 3, although they were not indicated by them, they were part of those I selected based on the specialized literature, as shown in the following table:

Table 1 Frequency of cases mentioned

| Cases | Mentions | Total | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abortion in Mexico City | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |||||||

| Aguas Blancas | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||||||||

| Gay marriage and gay adoption in Mexico City | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||||||||

| Budget veto | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||||||||

| Lydia Cacho's torture | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | |||||||||

| Anatocism | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||||||||||

| Florence Cassez | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||||||||||

| 49 children dead in a daycare center fire | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||||||||||

| Televisa Statute | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||||||||||

| Marijuana | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||||||||||

| Poet case: national symbols & freedom of… | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||||||||||

| Atenco | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Electoral districts | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Rosendo Radilla Pacheco | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Ulises Ruiz | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Instituto Federal de Telecomunicaciones | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||

| House imprisonment | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Auditoría Superior de la Federación | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Presidential flight logbook | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Independent candidates in Yucatán | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Jorge Castañeda (independent candidate) | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Grounds for divorce | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Celaya | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Consulta reforma energética | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Constitution as mandatory norm | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Human Rights, constitution & International treaties | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Gender Quota | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Union dues not subjected to transparency | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Delicias | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Fobaproa | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 1971 student massacre in Mexico City | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Candidates' illiteracy | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Servicio Público Energía Eléctrica Statute | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Free business association | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Militarization of Public Security | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Extension of public office mandates | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Transgender identity | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Government publicity | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Jehovah's Witnesses | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| HIV among militaries | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Spousal rape | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Forced Disappearence of Persons | 0 | ||||||||||||||

| Protection of life in Baja California | 0 | ||||||||||||||

| Protection of life in San Luis Potosí | 0 | ||||||||||||||

| Ansolabehere | Caballero | Cárdenas Gracia | Fix-Fierro | Gómez Mont | Gómez Pérez | Góngora Pimentel | Ortiz Mayagoitia | Pozas Horcasitas | Salazar | Silva Meza | Tortolero | Valadés | Woldenberg | ||

In the table above, the cases are presented according to the frequency of mentions in descending order. That is, from the most mentioned to the least mentioned. The cases that do not correspond to the temporal delimitation of this research (other than the 19952011 period) are marked in light gray so that the reader can identify them. Those marked in black correspond to the cases that are within the period studied and that were analyzed in this research. And those in white are the cases that, although they belong to the period, were not analyzed.

Cases selected

Based on the democratic dimensions -and contrasted with the literature and the interviews-, 9 cases were finally selected. In Mexico, we name cases making reference to the kind of case, the file number and year (e. g. Controversia constitucional 33/2002). Since that would not be clear enough, I decided to give each case a short title so that it can be easily identified. The cases are:

-

1) Poet case: national symbols and freedom of expression

(Amparo en revisión 2676/2003)

-

2) Prescription and non-retroactivity on forced disappearance of persons

(Controversia constitutional 33/2002)

-

3) 1971 student massacre in Mexico City

(Facultad de investigación 1/2006)

-

4) Abortion in Mexico City

(Acción de inconstitucionalidad 146-147/2007)

-

5) Transgender identity

(Amparo directo civil 6/2008)

-

6) Protection of life in Baja California

(Acción de inconstitucionalidad 11/2009)

-

7) Protection of life in San Luis Potosí

(Acción de inconstitucionalidad 62/2009)

-

8) 49 children dead in a daycare center fire

(Facultad de investigación 1/2009)

-

9) Gay marriage and gay adoption in Mexico City

(Acción de inconstitucionalidad 2/2010)

The first case deals with a writer, Sergio Hernán Witz Rodríguez, who published a poem, in 2001, in a cultural magazine in which he said that he would clean "his ass with the [Mexican] flag". He was prosecuted for the crime of outrages against the national symbols as provided for in article 191 of the Federal Penal Code. The case reached the Supreme Court seeking to declare article 191 unconstitutional for violating the freedom of expression, but the justices did not consider it so and, therefore, granted no constitutional protection to the poet.

In the second case, the Mexican government approved the Inter-American Convention on Forced Disappearance of Persons. However, the government made a reservation and an interpretative declaration of the convention. The reservation was made on the specialized military jurisdiction. The interpretative declaration indicated that these crimes would be prosecuted only after the entry into force of the convention, in observance of the principle of non-retroactivity. Mexico City's governor disputed the federal government reservation and interpretative declaration. The Supreme Court did not rule in favor of the Mexico City's governor and, therefore, declared that both the reservation and the interpretative declaration were constitutional.

In the third case, the Supreme Court was requested, in 2006, to investigate the student massacre that occurred on June 10th, 1971, known as "el halconazo". This massacre was perpetrated by the Mexican army and is considered as one of the most outrageous abuses in Mexico's contemporary history. In 2006 (when the request was issued), the Supreme Court was authorized by the constitution to inquire about human rights violations. Although the crimes related to that massacre were about to prescribe that same year, the Supreme Court decided not to investigate.

The fourth case is about abortion in Mexico City. In 2007, a reform was made to allow the free termination of pregnancy within 12 weeks. The Supreme Court decided that the reform and, therefore, the termination of pregnancy were constitutional.

The fifth case deals with a transgender person. At birth, she was identified as a male, but during puberty her breast grew. Later, doctors discovered that she lacked testicles and, instead, she had an ovary. Although it seemed that she had both sexes, her real sex was female. She requested the change of name and sex, as well as the issuance of a new birth certificate. The purpose of issuing a new certificate was to assure that such modifications were not known to the public. A judge granted her the change of name and sex, but not her claim regarding the new birth certificate; in 2008, the case reached the Supreme Court and the justices determined the issuance of a new one.

The sixth case is about protection of life in opposition to women's liberty. In 2008, Baja California's state constitution was reformed to protect life from the moment of conception. In 2009, the reform was challenged since it might restrain women's rights. However, in 2011, the Supreme Court did not consider it unconstitutional. Therefore, the norm is still in force.

The seventh case took place in the state of San Luis Potosí and it is identical to the last one. The state constitution of San Luis Potosí was reformed to protect life from the moment of conception. Again, the Supreme Court did not consider such reform as a women's rights violation and, therefore, did not declared it unconstitutional.

The eighth case deals with 49 children that died in a daycare center fire, in 2009, in Hermosillo, Sonora. The Supreme Court determined to investigate the case and decided, despite many disagreements among justices, that authorities were severely negligent and that there were serious violations of human rights.

In the ninth case, Mexico City's civil code was reformed to redefine marriage, ceasing to be the union between a man and a woman for procreation purposes, to be the union between two people and eliminated such purpose. Regarding adoption, although it was not itself amended, it was implicitly modified by the redefinition of marriage: any couple could now adopt. The Supreme Court ruled that this reform -that protects the rights of the gay community- is constitutional.

Interpretation criteria

This research implies the intersection of two perspectives. If the selection of cases was determined by democratic theory, the criteria for interpreting them -as legal units of analysis- will have a theory of law approach. I will explain here each criterion as clearly and briefly as possible. Nonetheless, that implies a risk of generalizing. Therefore, if the correlations established in this paper are reasonable, I believe this section, related to legal philosophy, should be the subject of further debate.

Legal positivism and natural law constitute different ways of conceiving and interpreting the law. More specifically, these theories offer opposite answers to the question of when law is valid. Legal positivism is a simpler figuration or conception of law because it offers a reductionist approach towards a social phenomenon that is more complex.

It is necessary to acknowledge that there are different versions of positivism, in particular, it is possible to observe this diversity among contemporary theorists who try to offer answers to the severe criticisms inflicted upon positivism during the 20th century.

However, in this paper I will focus my target not on those contemporary theorists, but on those versions of positivism that Dworkin criticized (represented by classical authors like Hart and Kelsen). It is not that I underestimate or simply look in another direction deciding to ignore contemporary positivist theorists that came after Hart. It seems to me that their contributions are concessions to natural law in one way or another, and vary so much in their subjects that they are atomized and diverge from the point that I am interested in.

For instance, the positivist approach known as legal realism was against formalism and criticized the conception of law as a closed and complete system of norms. As Leiter (2017) points out, the realists were lawyers, not philosophers, and they had a greater interest in understanding how courts actually work. Leiter (1999) argues that legal realism is a branch of legal positivism and claims that positivism has no necessary relation to formalism: positivism is a theory of law, while formalism is a theory of adjudication (p. 1144).

Therefore, the opposition between legal realism and positivism is, as Guastini (2020) says, incorrect. On the contrary, legal realism preserved the thesis of the separation between law and morality. For example, Shapiro (2011) supports this positivist thesis of separation and understands the law as a plan and, consequently, rejects any moral basis of law. Joseph Raz, one of the most prominent legal philosophers, defends -based on the positivist thesis of the sources- that the law should be analyzed only from social facts and not based on moral arguments. Waldron (1999) is another theorist who has been understood as an exclusive positivist and a critic of the judicial review of legislation by judges. Nevertheless, Gallego (2019) points out that this interpretation of Waldron's work is incorrect and, instead, it is more in line with that of Dworkin.

As can be seen, contemporary positivists maintain the basic premises of the doctrine. Classically, legal positivism has claimed that to be valid the law must: 1) be created by an authority; 2) issued for a specific territory; 3) and follow certain procedures in its creation.

A first version of legal positivism, represented by Austin (1832), emphasized authority as an essential condition of validity. As Dworkin (2001) says, for this version of positivism, "a valid law must be adopted by a specific social institution" (p. VII). In other words, the law is the law because it has been created by the sovereign and, for that reason, it will be valid only in his domains.

Nevertheless, other versions of legal positivism anticipated the weaknesses of this authority-based explanation and pointed out that the validity of norms derives not from authority but from other norms (Hart, 2014, p. 72). Therefore, a law would be valid if it has been passed according to the formal procedures that pre-establish how law should be created.

I would characterize this positivist conception of law as normativist, which indicates that the social phenomenon of law is a closed circuit of norms, either because a norm would be the simple expression of the ruler's will or because some norms give validity to others.

This implies that the cruelty or injustice of law is irrelevant in terms of its validity. The creation of law either by an authority or in compliance with formal procedures will suffice for the law to be valid. Consequently, legal positivism excludes the relationship between law and morality.

For natural law, instead, law and morality are connected. There are versions of natural law that do not seek metaphysical solutions to the problems that morality poses. In fact, some versions are secular and liberal. Dworkin (2014b) goes further and states that law derives from morality (p. 20). The validity of norms is neither conditioned by the physical strength of their authors nor by other norms.

Dworkin (2014a) defends the existence of moral principles, that is, extra-legal norms or norms of a moral nature within legal systems. "I call 'principle' a norm that must be observed", Dworkin (2014a) states, "not because it makes possible or ensures an economic, political or social situation that is deemed appropriate, but because it is an imperative of justice, honesty or some dimension of morality" (p. 118). This conception could be labeled as principlism, as opposed to normativism.

If we accept that law and morality are connected, that would necessarily lead us to the debate on the nature of morality and, as consequence, to the question whether or not moral objectivity is possible. As Dworkin (2014b) says: "We cannot defend a theory of justice without also defending, as part of the same matter, a theory of moral objectivity" (p. 24). In other words, natural law holds by necessity an objectivist conception of moral values. Dworkin's (2014b) answer to the problem of moral relativism finds that moral objectivity is a matter of rationality (p. 57). But such claim is not new, it dates back many centuries.

Instead, positivism's variability (on authorities, procedures and territories) results in a subjectivist notion of moral values (Kelsen, 2002, pp. 79 and 80). The discrepancy in the subjective or objective nature of morality take us also to the universal or territorial conception of law. Since for legal positivism law comes in state sized bites, as Dworkin (2006) says, citizens' rights are granted for specific territories. Therefore, if one goes to the domains of another sovereign, other norms will rule. But if there is a moral foundation for law and if morality is objective, then citizens' rights would not have territorial boundaries as is the case with human rights.

The inherent nature of human rights is opposed to legal positivism: those rights are neither granted by any authority nor limited by territory. Furthermore, since their purpose is to protect human dignity from abuses of power, human rights have a liberal ground. In that regard, Sartori (2008) has criticized how legal positivism defends the formal validity of law at the moral expense of the limitation of power (p. 201). For Sartori, this reduction of law to formalism shows how legal positivism is indifferent -in the definition of what is law- to illiberal thinking.

Positivism was originally influenced by empiricism and, as Pérez Tamayo (2008) points out, it is characterized by its reductionism (p. 137). I claim -under Elias' figurational theory- that legal positivism is a less complex theory of law. I acknowledge that legal positivism allowed to take God out of the definition of law. Nevertheless, that metaphysical criticism unfortunately turned into moral skepticism. In my view, legal positivism is both affected by normativism and formalism, and as a result, it underestimates the role of morality and legitimacy. It is true that other versions of positivism avoid that reductionist conception of law, but in every effort of building a more complex theory they end up accepting natural law premises.

The postulates of some contemporary theorists, whose assertions may seem very novel to us, are part of an old tradition of thinkers. Max Weber long ago underlined the role that legitimacy plays in the exercise of power (2002, p. 172).15 Since the Middle Ages, the Scholastics already spoke of moral principles as part of legal systems (Tamayo y Salmorán, 2005, p. 147). In the 13th century, Thomas Aquinas (1997) argued that justice was the congruity of reason with itself, that is, the truth in morality is found in rationality (S. t., Ia, IIae, 18, 5, ad Resp.). The Spanish Scholastics -Francisco Suárez (1967) among them- followed Thomas Aquinas and stated that law is valid for four reasons: 1) because it is issued by an authority, 2) it complies with the formalities of creation, 3) it is just and 4) seeks the common good (De legibus, I, 13,1). These are the very theses defended centuries later by Austin (1832), Hart (2014), Dworkin (2014a) and Finnis (2000), respectively. While positivism reduces its description of what law is to the first two conditions of validity, natural law brings a more comprehensive theory acknowledging the four of them.

I believe that legal positivism not only lacks a historical approach but also offers a partial explanation of the validity of law and, therefore, reduces law to its formalities, without considering other validity criteria. As we can see, Scholastic natural law theorists recognized positivist conditions of validity as necessary, but not sufficient, and instead brought, from my point of view, a more ample and complex description of law.

Human rights -such as liberty and equality- are inherent and their basis is morality, which means that authority is linked to legitimacy. Furthermore, I believe that there is a moral substratum in law and that a defense of a theory of justice, as Dworkin (2014b) says, implies an objectivist theory of values. This contemporary conception of natural law is more compatible with the democratic, secular and liberal values of our complex and modern societies.

Ultimately, these theories of law have different figurations about power and human beings. Legal positivism has a subjectivist, territorial, normativist and formalist conception of law; modern natural law is, instead, objectivist, universal, principalist and liberal. These divergent theories have an impact on how we interpret the law.

III. Classification of cases

Among all the selected cases, only four of them were mentioned three or more times by the interviewees: abortion in Mexico City, gay marriage and gay adoption, the 49 children dead in a daycare center fire and the poet cases; being the first one (abortion in Mexico City) the most indicated. In the rest of the analyzed cases, two of them received only one mention (the 1971 student massacre and the transgender identity cases); and three did not get any (prescription and non-retroactivity on forced disappearance of persons, protection of life in Baja California and protection of life in San Luis Potosí).

In accordance with the methodology proposed in this research, I classified the cases in the following way. Only three out of nine were considered as contribution to democracy; the other six were not considered as such. The two tables below show the classification based on the philosophical interpretation criteria:

Tables 2 and 3 . Classification of cases based on the philosophical interpretation criteria

| Cases that did not contribute to democracy | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Poet | Forced Disapp. of P. | Student massacre | Protection of life BC | Protection of life SLP | 49 children dead | Total | |

| Criterion | ||||||||

| Liberal | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||||

| Formalist vs principalist | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Territorial vs universal | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Subjectivist vs objectivist | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Cases that did not contribute to democracy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Abortion | Transgender | Gay rights | Total | |

| Criterion | |||||

| Liberal vs formalist | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Liberal & principalista vs normativist | 1 | 1 | |||

Occasionally, a case could be classified, at the same time, into two criteria if it presented more than one characteristic. Therefore, the totals shown in the tables above reflect the frequency of criteria for each case.

If we observe the six cases that did not contribute to democracy, four of them were categorized as formalist. At being formalist, they undermined either the liberal or the principalist solution that could be given to the case. Among these four formalist sentences, three were specifically in opposition to the liberal solution; and one was in opposition to principlism. The poet, the 1971 student massacre and the 49 children dead in a daycare center fire cases were opposed to liberalism; and the case of forced disappearance of persons was opposed to principlism. In relation to the other two that did not contribute to democracy, both were considered as territorial and, at the same time, subjectivist, as opposed to universal and objectivist. These were the protection of life from conception in Baja California and San Luis Potosí cases.

Among those that did contribute to democracy, each of the three cases had a liberal solution. These were the abortion in Mexico City, the gay marriage and gay adoption, and the transgender identity cases. The last one was, to be more precise, liberal and at the same time principalist.

If there is a correlation between legal theory and democracy, I should show how the philosophical criteria of legal interpretation correspond to the democratic parameters of political systems. For that, the following tables present the classification but now according to the democratizing dimensions used in this research:

Tables 4 and 5 . Classification of cases based on the democratizing dimensions

| Cases that did not contribute to democracy | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Poet | Forced Disapp. of P. | Student massacre | Protection of life BC | Protection of life SLP | 49 children dead | Total | |

| Democratizing dimension | ||||||||

| Rule of law (against) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | |

| Public debate (against) | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Transparency (against) | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Political participation | 0 | |||||||

| Cases that did contribute to democracy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Abortion | Transgender | Gay rights | Total | |

| Democratizing dimension | |||||

| Rule of law (via equality) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |

| Rule of law (via liberty) | 1 | 1 | |||

| Public debate | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Transparency | 0 | ||||

| Political participation | 0 | ||||

In the cases that were not considered as a contribution (and whose sentences were all classified as positivist as well), it can be observed that democracy was affected because they undermined the rule of law.

Nevertheless, in the specific case of the poet, its formalist sentence deteriorated not only the rule of law but also the public debate (as it constrained the freedom of expression). In the case of the 1971 student massacre, its formalist solution affected the rule of law, transparency and public debate.

Regarding the sentences that did contribute to democracy (and whose sentences were in line to natural law), they all gave rise to the rule of law. To be more precise, the three cases (abortion, transgender identity and gay rights) strengthened the rule of law through equality, that is, they promoted the equal treatment of women, transgender and gay people.

However, in the abortion case, I believe that in addition to contributing to the rule of law through equality, it also did so via liberty, since the free termination of pregnancy is also a liberty for women.

Besides, the Supreme Court decision was so controversial and concentrated so much attention that it also triggered the public interest in this matter. Actually, most of the interviewees agreed that the abortion and gay rights cases stimulated the public debate in Mexico.

IV. Justification

Now I will justify why I classified the sentences as I did. I will start with the cases that contributed to Mexican democracy and, then, I will continue with those that did not.

In the abortion case, the Supreme Court had to decide whether or not the reform in Mexico City that allowed the free termination of pregnancy within 12 weeks was constitutional. The Supreme Court not only openly adopted a human rights perspective but also explicitly carried out an exercise that, in legal argumentation, is called weighing and balancing: the justices had to solve the conflict between two principles or moral values (life and liberty). They first recognized that life, although not clearly expressed in the Mexican constitution, is a constitutional value. Nevertheless, that did not imply that life should be set above liberty. They decided to stand up for the liberty of women. In addition, the case offered the first amicus curiae in the history of our constitutional court and opened the public debate. Thus, the Supreme Court weighed and balanced two moral values; adopted a human rights perspective; and by defending women's liberty, it promoted women's equality towards men and triggered the public debate. Therefore, it contributed to democracy.

In the transgender identity case, the court of first instance rejected to issue a new birth certificate because such issuance was not contemplated by the law. The Supreme Court refused to make that normativist interpretation and, instead, claimed to that a case like this should be explicitly adjudicated under the doctrine of principles. Legalist interpretations and lacunae in the law should not impede, according the justices, to issue the birth certificate requested; this approach led them to identify certain rights or values that had to be protected in this case: equality (to avoid discrimination), liberty (as free development of personality, lifestyle choices and personal identity) and privacy. Consequently, the Supreme Court rejected the normativist interpretation, adopted a principalist perspective and protected human rights. By defending the right to equality, the Supreme Court contributed to democracy.

Regarding the case of gay marriage and gay adoption, Mexico City's civil code was reformed to established that marriage is the union of two people. It was no longer: a) the union of a man and a woman, and b) for procreation purposes. Although adoption was not explicitly modified, it had changed by the new definition of marriage: any married couple is now entitled to adopt a child. The Supreme Court conducted an analysis known in legal argumentation as reasonableness. It concluded that in some cases it is reasonable to limit some rights to some citizens, but in this one, there is no justification for not granting the same liberties to gay people. As to adoption, the justices stated that there is no scientific evidence that shows that gay parents affect the development of adopted children, therefore, again, no limitation is justified. On the contrary, not granting the gay community the rights to marry and adopt is a violation of equality. For that reason, the decision of the Supreme Court is a contribution to the Mexican democracy.

Now I will deal with the cases that did not contribute to democracy. In the case of the poet, the Supreme Court avoided to decide whether or not the article of the penal code, by which the writer was prosecuted, was unconstitutional. For that, it employed a formalist excuse. First, the Supreme Court made a simplistic effort to find a constitutional subterfuge: the Mexican constitution holds that the legislative branch has the power to regulate the national symbols and, therefore, the justices claimed that the article 191 of the penal code is an expression of that prerogative. In my view, there is no doubt that there is a legal basis in Mexico to regulate the national symbols. Nevertheless, that was not the matter. The Supreme Court did the opposite of what a constitutional court should do: to decide if the referred article violated the constitution and, specifically, the freedom of expression. In other words, a writer published an innocuous poem that depicted the disappointment he felt towards his own country and a prosecution was launched based on the penal code. The Supreme Court did not see there an abusive regulation. Instead, it simply offered a formalist justification for such regulation. The decision not only eroded liberty but also diminished the idea that authority should be limited to avoid abuses. Consequently, it weakened the rule of law, the public debate and the Mexican democracy.

The case related to the Inter-American Convention on Forced Disappearance of Persons brought controversy in Mexico when the federal government approved that treaty issuing a reservation and an interpretative declaration. The reservation intended to assure the specialized military jurisdiction provided by the Mexican constitution. The purpose was that the military involved in forced disappearances were not investigated under the rules of the convention by civil authorities. The interpretative declaration sought that the crimes committed before the entry into force of the convention would not be prosecuted in observance of the principle of non-retroactivity established in the Mexican constitution. Mexico City's governor disputed the reservation and the interpretative declaration because he considered that the federal government aimed to guarantee impunity. Nevertheless, the Supreme Court declared that both the reservation and the interpretative declaration were constitutional. For that, it employed again a formalist justification: the Mexico City's governor did not prove that he had the right to dispute the reservation and the interpretative declaration. The argument is very questionable: for the Supreme Court, the governor had no interest in the case since he did not show how it would affected Mexico City's jurisdiction (the alleged criminals charged of forced disappearance, such as the military, would be federal authorities, while the judicial system of Mexico City could only prosecute local authorities). According to the Supreme Court, Mexico City was not affected and the governor had nothing to do with this case, so the claim was dismissed. In my view, such argument is very poor The Supreme Court avoided studying the constitutionality of the reservation and the interpretative declaration. It did not address the real issue and postponed the solution to the Mexican undemocratic problem of specialized military jurisdiction (which anyway the Supreme Court years later ended up solving). The Supreme Court's formalist reluctance to make authorities accountable for their crimes was against the rule of law.

As for the case of the 1971 student massacre, the Supreme Court opted once again for a formalist solution. On June 10th, 1971, the Mexican army was deployed to suppress a student demonstration that turned into a massacre. Decades later, in 2006, when the crimes were about to prescribe, a request was correctly made to the Supreme Court to investigate the case. In Mexico, the Supreme Court had the power, according to the constitution, to investigate human rights violations. Nevertheless, the Supreme Court decided not to investigate and dismissed the case. "This matter had already been legally solved", the Supreme Court said, in the sense that it had been proven that the army indeed perpetrated the massacre. But as justice Cossío Díaz pointed out in his dissenting opinion, that was wrong: there was no certainty that all the crimes that were committed had been thoroughly clarified. Besides, not one person was taken to court and held accountable. The Supreme Court's decision blocked the way to fight impunity. It undermined not only the rule of law and transparency, but also the public debate of a historical and troublesome matter in Mexico. In short, it did not contribute to democracy.

The two cases of protection of life from the moment of conception (in the states of Baja California and San Luis Potosí) infringed women's liberty. Justice Luna Ramos presented territorial and subjectivist arguments: if the federal constitution is not explicit on this matter, any state constitution could define and protect life in its own way, implying that it could change from place to place. Justice Aguilar Morales held, instead, that human rights are universal and they do not change from state to state. Justice Valls Hernández claimed that this apparent expansion of rights (the protection of life from the very moment of conception) meant the violation of other rights (the liberty of women). Justice Cossío Díaz said that an absolute protection of life would cancel any possibility of weighing and balancing. Although most of the justices were in favor of women's liberty (7 out of 11), they could not declare the disputed articles unconstitutional. In Mexico, justices need a qualified majority of 8 votes out of 11 in cases like these. Therefore, the articles of those local constitutions that violate women's rights are still in force.

In the case of the 49 children that died in a daycare center fire, the Supreme Court accepted to exercise its prerogative to investigate human rights violations. Nevertheless, the justices expressed several disagreements among them. They decided that the authorities' negligence was the cause of this tragedy and resulted in a violation of human rights. But the justices also explicitly exhibited their reluctance to investigate. They were not capable of pronouncing a sentence with a single voice, instead, they pulverized their decision by dividing the case in many different aspects and, in each one, they did not reach a real consensus, which is evident when the votes are analyzed. They decided, for example, that the owners of the daycare center were not involved in the violation of human rights simply because they were not authorities (an outdated principle that the Supreme Court itself rejected years later). This case exposed the unwillingness of the Supreme Court to investigate human rights violations. In fact, one year later this prerogative was eliminated from the Mexican constitution. Thus, this was the last time it was exercised. The discomfort of the Supreme Court in this sort of cases weighed more than the constitutional mandate to enforce the rule of law, the human rights and the Mexican democracy. Until today not one person is in jail for the death of those 49 children.

V. Conclusion

The turn in the methods of legal argumentation has been fundamental in countries such as Mexico for the contribution of the courts to democracy. Those methods are related to the philosophical theories of law and reflect the mentalities and attitudes of judges. Historically, the Mexican Supreme Court had been a positivist institution. Its normativist conception of law has implied a legalist approach when justices adjudicate and its emphasis on formalities has had a negative outcome for democracy.

It is not a coincidence that the sentences that did not contribute to democracy (as in the cases such as of the poet, the forced disappearance of persons, the 1971 student massacre, the protection of life in Baja California and San Luis Potosí, and the 49 children that died in a fire) were all decided based upon a reductionist conception of law. The Supreme Court justices preferred to avoid the genuine constitutional substance by dismissing each case with syllogistic arguments.

The nature of those arguments allows us to perceive how justices understand and interpret the law. Although judges' philosophical points of view are not necessarily conscious, their attitudes are in line with premises of one or another legal theory. Some justices even expressed concern towards non-positivist figurations. In fact, that was pointed out by the interviewees when they described the Mexican Supreme Court as positivist.

The natural law tradition states that law is composed of moral values and, therefore, it cannot be reduced to a set of rules. There are cases that entail the conflict of moral principles and non-positivist argumentation has developed methods for solving these types of problems, as it has happened in the transgender identity, abortion and gays' rights cases. The figuration of law that embraces moral values and defends human rights has an impact on democracy. The decisions of judges and their philosophical core affect the democratization of the political systems. There is an unequivocal correlation between that conception of law and the strengthening of democracy.

Modern democracy (i. e. liberal democracy) involves the protection of human rights which is only possible through the limitation of power. For Sartori (2008), Austin's analytical philosophy and Kelsen's positivism reduce law to its form, that is, to legalism (p. 201). Sartori argues that a formalist interpretation can lead to atrocities and dilute the purpose of constitutionalism. "Law will defend us less from oppression", Sartori says, "the more we tolerate a purely formal and positivist interpretation of it. If it is enough for the law to have 'form of law' and if at the same time legality engulfs legitimacy, then nothing prohibits the tyrant from exercising his tyranny in the name of law and by orders disguised as laws" (p. 202).

According to Elias' figurational theory, the partial and reductionist explanation of law that legal positivism offers should demonstrate that natural law is a more complex theory. This debate between legal positivism and natural law might seem tedious and outdated for many scholars. Nevertheless, I believe that this matter is not unimportant for the young Mexican democracy. Especially if we realize that there is tangible evidence that when democratic transition occurred in Mexico, the Supreme Court experienced a shift in its role as a real counterweight in the political system and in its relationship with legal theory and, by extension, with human rights. All these changes would have been unthinkable before.

The Mexican Supreme Court has contributed to the democratization of the political system, but it has been a moderate contribution. As it has been shown in this paper, the cases corroborate the correlation: its most effective contribution was when it was faithful to its work as a constitutional court and opted for non-positivist methods of argumentation.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)