Summary: I. Introduction: “Disagreement in Action”. II. Is Making Room for Moral Combat in Our Morality Necessary Because it is an Inevitable Feature of Our Moral Experience? III. Constructing a Logic for Morality that Has the Potential to Rule Out Moral Combat as a Possibility. IV. Conclusion. V. Appendix; Brief Introduction to Deontic Logic. VI. References.

I. Introduction: “Disagreement in Action”

This paper was first written for a conference entitled, “moral disagreement, its nature, varieties, and possible resolution”. We took the speakers-meaning behind this title to have referred to cognitive disagreements, that is, disagreements in belief about: what is and what is not a good state of affairs; what is and what is not right action; and even what “goodness” and “rightness” mean when used as terms of moral appraisal. Some allowance was also no doubt intended to be made for the non-cognitivists amongst us, so that the topic could also reference disagreements in attitude, mood, or emotion. Such disagreement in attitude has to be added to disagreements in belief so as not to beg all the important questions raised by a distinguished meta-ethical tradition, namely, that of non-cognitivism.

These kinds of disagreements are different from what we shall call disagreement in action, not in attitude or in belief. This is a different kind of disagreement, and it is one that we wish to here examine. The thought is this: perhaps morality itself is so structured that what is obligatory for one person to do is obligatory for another person to prevent the first from doing. Such pairs of actors needn’t disagree in their moral beliefs or attitudes about what is right action for each of them on a given occasion. Nor need one of them be making some moral mistake in acting as she does - each can be acting rightly even though one’s right action will frustrate the other’s right action. Or at least that is the possibility that we wish to explore.

There are a number of reasons to explore disagreement in action in the larger context of moral disagreement generally. One is that it is a form of moral disagreement in its own right, as much so as disagreement in attitude, emotion, or belief. Another is its relevance to the latter kinds of moral disagreements. One reason to care about disagreements in attitude or belief is political: given the existence of such disagreements, some modus vivandi or other form of political accommodation must be discovered and put in place if a peaceful social life is to be achieved; yet if there is disagreement in action that remains after all disagreements in belief or attitude have been accommodated in some such way, such political accommodation can be at best partial because conflicts between actors will remain. Another reason is meta-ethical: disagreements in attitude or belief might be taken as evidence that there is no fact of the matter to be agreed upon, as John Mackie argued years ago with his “argument from relativity”;1 yet if the meta-ethical realism that Mackie was arguing against turns out to be a realism about a morality whose content legitimates both sides in conflicts between persons, then the difference between such realism and its meta-ethically relativist opponent seems much less important. Actors opposing one another in a substantive morality that permits or requires disagreement in action will look a lot like actors opposing one another because they each believe they are right and there is no fact of the matter to settle the question (i. e., meta-ethical relativism). Yet another reason is epistemological: in assessing just how much disagreement in attitude or belief there is about morality in contrast to science -a concern of both the political and meta-ethical reasons explored above- it is easy to inflate the amount of such disagreement if one confuses disagreements in action as evidencing disagreements in belief or attitude; while this is a mistake that can and should be avoided, it would be a common one for actors to make as they judge the rightness of their cause vis-a-vis the rightness of their opponents’ causes, if there is such a thing as disagreement in action.

For these reasons we thus focus on disagreements in action in morals. One of us some years ago described a morality that would conceive of such disagreements in action, as a morality of “moral combat”.2 We shall take the remainder of this introduction to clarify just what such moral combat is and why it would be an unfortunate attribute for any morality to have.

The moral combat that interests us is not to be confused with a different kind of disagreement in action that is also possible. We refer to a conflict of rights between two or more different people such that a third party faces a conflict in the correlative duties he owes to each of the two or more rights-holders. With respect to the latter kind of disagreement in action, it is standardly thought that morality rules out the possibility of there being conflicts in the obligations binding a single actor, conflicts demanding contradictory actions by that actor on a given occasion. Standard deontic logic is conceived to be such that it is not possible for it to be the case that one person, X, is obligated to another person, Y, that X do and that X not do one and the same action, A. In the symbolism that we will use throughout the paper, ~[X OB Y (X do A) and X OB Y (X not do A)]. One reason one might think otherwise is if one moves from all-out obligations to those pro tanto (or “prima facie”; or “componential”) obligations that many think make up the ingredients out of which conclusions about all-out obligations are forged. Yet conflict between merely prima facie duties is harmless enough, because at the end of the day there need be no conflict in what a moral agent is obligated to do on a given occasion.3 But aside from this harmless concession to there being conflicts in obligations that are prima facie only, only those with a tragic and pessimistic view of the inevitably sinful lot of man can think that morality flatly and all-out commands us both to do something and not to do that same thing. For such a morality guarantees each of us moral failure no matter what we do.

Seeing that there is this other kind of disagreement in action -conflict of obligations- is helpful in isolating the kind of disagreement in action that we call moral combat. Moral combat is the inter-personal analogue of such intra-personal conflict of obligations. Take a version of Cicero’s ancient example of two men on a plank that can only support one. After a shipwreck, two mothers, X and Y, are strugling to keep their infant children alive in the open sea. There is but one plank available to save anybody. It is insufficient to support either adult mother; it is also insufficient to support both infants; it is sufficient to save one infant. Both mothers reach the plank at the same time; at t1 both seek to place their infant on the plank; simultaneously each seeks to prevent the other from succeeding in placing that other mother’s child on the plank. Despite these preventative efforts, both infants are on the plank anyway, and it is sinking. At t2, each mother seeks to throw the other’s infant off the plank to its certain death; simultaneously each seeks to prevent the other from doing this.

On the interpretation of the moral landscape here that we wish to examine, this is a situation of moral combat. At t , X is obligated to put her child (“X1”) on the plank, and at the same time, Y is obligated to prevent this innocent threat to her own child (“Y1”); and vice-versa when the parties are reversed. Further, still at t1, X is obligated to prevent Y from preventing X from placing X1 on the plank; Y is obligated to resist this preventative action by X; and vice-versa when the parties are reversed.

At t2, X is obligated to throw Y1 from the plank so as to save X1; Y is obligated to resist the killing of Y1 by X should X seek to fulfill her obligation; and vice-versa when the parties are reversed. Further, still at t2, X is obligated to resist Y’s efforts to prevent X from throwing Y1 from the plank; Y is obligated to resist this preventative effort by X, and vice-versa when the parties are reversed. Finally, at both t1 and t2, X’s friends are permitted (or, depending on the relationship of the parties, perhaps obligated) to help her in each of X’s efforts to fulfill her obligations; and Y’s friends are likewise permitted/obligated to help her in each of Y’s efforts that fulfill her obligations.4

Let us call conflict between the obligations of two people, “strong moral combat”. It is strong in the sense that both sides of the conflict are obligated, one person being obligated to do something that will prevent another person from fulfilling her obligation. The two mother’s competing for one plank, if this turns out to be an instance of moral combat at all, would be an example of strong moral combat. But we also need the concept of weak moral combat. Cicero’s original versions of his two-on-a-plank example night be an instance, depending on how it is construed:5 each of two men on a plank that can only support one are permitted to throw the other off to his death. Since each has such a permission, each is morally permitted to engage in active combat. Absent some Christian-like obligation to preserve one’s own life, each is not obligated to engage in actual combat, as is true in strong moral combat situations: but each is permitted by morality to do so.

Seeing that there can be cases of weak moral combat also allows one to see what we might call mixed cases of moral combat. These are cases where one person is obligated to do something where another is permitted to ensure that that thing is not done, or where one person is permitted to do something that another person is obligated to see is not done, e. g.: a mother fighting to save her child on the proverbial plank against an adult trying to save himself. One kind of mixed moral combat is illustrated by thinking that the adult is permitted (but not required) to throw the child off the plank where the mother is obligated to prevent that. The other kind of mixed moral combat is illustrated by thinking that the mother is obligated to throw the adult off the plank to save her child when the adult is permitted (but not required) to prevent that.

Kant famously proclaimed that a conflict of duties was “inconceivable”.6 To be obligated both to do some action, and not to do some action, was outrageous, so outrageous that Kant thought that morality couldn’t possibly be so constituted. Notice, however, that it is not “inconceivable” in the sense that it would be contradictory to think that morality is so constituted.7 While it would be contradictory to think both that one is obligated to do A and that it is not the case that one is obligated to do A (external contradiction), it is not contradictory to think that morality obligates us both to do, and not to do, one and the same action (internal contradiction only). Still, it would be a wildly unfair morality for us to be moral losers no matter what we did. Some malevolent Greek god might foist such an unfair morality off onto the human race just for his own amusement in watching a struggle where the outcome was guaranteed to be moral failure no matter how pure the heart or strong the will; but it is hard for non-theists (or theists with a more benevolent god in mind) to imagine that morality gives us no chance to do the right thing.

Suppose the malevolent Greek god takes this lesson to heart, and thus creates a morality that obeys one of the strictures of standard deontic logic: it is not the case that one can be obligated to do A if one is obligated not to do A, and vice versa. In other words, OB(A) and OB(not-A) are contraries of one another; both cannot be true (although neither could be true which is why they are only contraries and not contradictories). Still, the god likes his fun with the human race. So he arranges things so that collectively (rather than individually) human beings cannot morally succeed: one person’s moral success necessarily comes at the cost of another person’s moral failure. The two mothers with children on a plank is a seeming illustration of one form of such guaranteed collective failure. While both mothers can fail in their obligations (both children drown), at most only one can succeed in doing what she is obligated to do. This second game is almost as enjoyable to the malevolent Greek god as the first, because collective success will elude the humans in this game as certainly as it eludes an individual in the case of conflicting obligations.

Our name for these latter kinds of situations is, “moral combat”. The argument is that such situations would be undesirable because they make each of us act as moral gladiators against our fellow moral agents. It is as unfair to us collectively as conflict of ob ligations would be unfair to us individually. Morality demeans us in both cases, by obligating us in a way that guarantees that we all cannot satisfy morality no matter that each of us is pure of heart and strongly motivated to do what is right.

We thus take moral combat to be as unfair to those subject to such a morality as would be conflict of obligations. If we were thorough-going consequentialists about morality, we could bolster this argument based on fairness with one based on the impossibility of the same state of affairs being both good and bad, depending on who is bringing it about. For the agent-neutral perspective distinctive of consequentialist ethics seemingly rules out any possibility that one actor can be right in causing some state S to exist while another actor can be right in preventing the first actor from bringing state S about -for how state S is brought about, and by whom, should be irrelevant to such agent-neutral evaluations.8

But we are not consequentialists, at least not exclusively so, in our theories of morality.9 And given the agent-relative nature of the most plausible deontological theories, there is no deontological argument against the possibility of moral combat existing as there is for consequentialists.10 Still, moral combat is no less unfair for deontologists than for consequentialists. A decent morality would not allow it if it can avoid doing so.

The topic we take up in the next section is whether morality can avoid situations of moral combat. We shall there pursue whether moral combat is an ineliminable feature of our moral experience. This we do by probing various situations where actual combat exists and asking whether each opposing side could be right in their opposing actions. (For those who cannot stand the suspense, we conclude that there are no such situations in common moral experience.) In the second half of the paper, we then seek to develop a “logic of rights” that rules out the possibility of moral combat. We do this because on a quite standard view of such a logic -namely, that derived from the legal theorist Wesley Hohfeld- considerable moral combat is both permissible and to be expected. Yet since we think it to be as desirable to rule out moral combat in a logic of rights as it is to rule out that other kind of disagreement in action (conflict of obligations) in standard deontic logic, we seek to supplant Hohfeld’s logic of rights with our own.

II. Is Making Room for Moral Combat in Our Morality Necessary Because it is an Inevitable Feature of Our Moral Experience?

1. Getting the Question Straight

The question pursued here is whether it is plausible that life presents us with situations of moral combat. Notice that the question is not whether life presents us with situations of actual combat. The answer to that question is obvious: it does. Rather, the question is whether morality sanctions each side of some actual combat, making each of such opposed actions the morally right thing to do. An action can be the morally right thing to do because doing it fulfills some obligation of the actor; or it can be the right thing to do if the actor has what is standardly called an active right (i. e., a permission) to do it.11

To see our question aright requires familiarity with two items. First, one needs enough familiarity with standard deontic logic to understand the meanings assigned to the operators for obligations (“OB”), permissions (PE”), and options (“OP”) by that logic. For those unfamiliar or rusty with the standard deontic logic that developed from the Aristotelean “Square of Opposition”, we have provided a brief and introductory summary in the Appendix.

The second thing needed here is to overlay the standard deontic operators of obligation, permission, and option so as to accommodate the notion of rights, both active and passive. One does this by initially identifying passive rights in one person as simply the correlative of an obligation owed by another person to that first person; further, we initially identify active rights as the permissions of standard deontic logic. However, in making this second identification we need to introduce distinctions between different kinds of such permissions. We need to introduce a distinction between strong versus weak permissions. There are in truth a number of distinctions drawn in these terms. Joseph Raz, for example, characterizes a permission as strong if it is created by an explicit moral or legal norm, weak if it is merely an absence of obligation.12 Moore in the context of discussing agent-centered prerogatives characterizes a permission as strong if it permits one to do an action not maximizing of good consequences, weak if it is merely the absence of deontological obligation.13 Kramer characterizes a permission as strong if there is an absence not only of an all-things-considered obligation but also of a prima facie obligation, weak if it is only an absence of the former but not the latter.14

We intend here a different distinction. A permission is strong in our sense if one of two things is true: either the permission is also an obligation on the part of the holder of the permission to do the action he is permitted to do; or the permission, although based on an option and not on an obligation on the part of the permission-holder, nonetheless imposes an obligation on the part of another not to interfere with the act the permission-holder is permitted to do.15 A permission is weak, by contrast, only if two things are true of it: first, there is an absence of any obligation to do or not to do the permitted action (i. e., the permission is based on an option); and second, there is no obligation on the part of others not to interfere with the doing of the action permitted -there is only what Hohfeld called a “no-right” on the part of others that the permission-holder not do the action he is permitted to do.16 Following Bentham, we shall call such weak permissions, “naked liberties”.17

With both of these preliminary steps taken, we can now more precisely frame our question. The way to misconstrue our question is to think that, fundamentally, the question is asking whether one’s person’s “naked liberty” to do A can conflict with another person’s “naked liberty” to prevent A. It is no part of our thesis to deny that naked liberties can exist and can conflict. A naked liberty to do A, as we have just defined it, is an option to do A but it is naked in the sense that renders it devoid of any moral significance: it is not an implication of an obligation, nor does it have as a correlative that anyone has an obligation to do anything to further or prevent its exercise; it has as a correlative only the Hohfeldian minimum: others have no right that one not exercise the option. Naked liberties, thus, are devoid of moral significance. They are only the absence of obligation on the part of the option holder, and the absence of rights on the part of everyone else. Unlike double negation in logic, two absences do not make for a presence. Morally speaking, naked liberties are nothing at all - no more than an absent elephant is a ghostly kind of elephant, or an absence of two elephants is a ghostly herd of ghostly elephants.

Judith Thomson gives a humdrum, every day example:18 we each have an option to pinch our own nose on almost all private occasions in life. We are not obligated not to do so, and we are not obligated to do so. As Thomson rightly notes, our life is full of such optional actions; put another way, most of our daily choices are not governed by duties -either ours or others- so of course those choices are exercises of our naked liberties. Moreover, such naked liberties can and often do conflict: often one’s person’s option puts them in competition with another person’s option in the sense that success of one prevents the success of the other. Thomson thinks that is true of her pinchone’s-own-nose example but that is hard to see in light of each person’s exclusive right to his own bodily integrity.19 A better example is “first come, first served” buffet lines where but one dessert remains; X and Y are equally optioned to take the dessert, but when X exercises her option she prevents Y from exercising his.

Such humdrum examples do not provide instances of moral combat, however much they may present instances of actual combat. This is why Hurd explicitly puts aside such cases as irrelevant to her defense of there being no moral combat whenever we act as of right:

[I]f there are [naked] liberties ...of the Hohfeldian sort, they define arenas of amoral action. Actors within such arenas are not bound by any maxims of action -they are genuinely at liberty. It is not the case that they are obligated to act in certain ways, but it is also not the case that they have rights (or commonly understood permissions) to act in certain ways (because, on this argument, liberty is not a right). Hence, actors operating under [these] liberties are untouched by deontological norms. That their actions may conflict is thus of no normative importance, because their actions are of no normative importance. They are the actions of those in a moral state of nature.20

We will return to this “state of nature” characterization later as we deal with examples more morally charged than pinching one’s nose or picking one’s dessert.

2. In Search of Situations of True Moral Combat

Having narrowed the class of examples we need consider, what is left? Not much, as it turns out. Consider the following, rather heterogeneous list of possibilities culled from the literature sympathetic to the Hohfeldian analysis of rights.

A. Situations of Warfare and Actual Combat

In what was said to be Nixon’s favorite film, Patton, General Patton is depicted as urging the soldiers under his command to kill Germans and not to let the Germans kill them (George C. Scott’s version: “Don’t you die for your country; make the other bastard die for his country”). Supposing that Wehrmacht officers gave German soldiers the same orders, is this a situation of moral combat? Strong moral combat (combatants are each obligated to kill the other, and obligated to prevent that other from killing them)? Weak moral combat, where each are permitted to do both of these things? Or mixed moral combat, where one is obligated (the one fighting a just war) and the other is permitted (one fighting an unjust war but retaining self-defense rights)?

In his illustration of conflicting rights (necessitating recourse to Hohfeldian construals of these rights as mere privileges unaccompanied by claim-rights), one of the Yale Law Faculty’s early enthusiasts for Hohfeld, Arthur Corbin, gave two such war-time examples.21 A neutral ship owner may ship contraband to a belligerent but the opposing belligerent may seize that contraband to prevent it reaching its destination; a neutral ship owner may seek to run a blockade but the blockading belligerent may sink the ship and thus prevent the running of the blockade. Hurd adds to these war-time examples the war-like examples of conscripted gladiators, each of whom may not be obligated to kill the other or obligated to prevent themselves from being killed by the other (no strong moral combat), but each of whom might well seem to be permitted to do these two things (weak moral combat).22

Some have the “state-of-nature” response to these kinds of situations. “War is war”, they say, and morality creates neither obligations nor permissions but only liberties unaccompanied by claim-rights (i. e., “naked liberties”). This is not the line we take here. Killing other people is not morally inert in the way that choosing blueberry dessert or scratching one’s nose usually is.

In the cases put, if one side is fighting a just war, and the other is not, these become easy cases in which there is no plausible moral combat. Soldiers or gladiators on the unjust side are not obligated or permitted to kill those fighting on the just side, so there can be no moral combat between the combatants. Those fighting on the unjust side may have an excuse (of ignorance or coercion); but that would be irrelevant to moral combat, which is conflicts in right action not in the culpability of actors. (We reserve for separate, later discussion whether those fighting on the unjust side might have a right -i. e., a protected permission- to defend themselves).

Likewise, these cases become easy instances of no troublesome moral combat if the combatants are volunteers -paid mercenaries, willing gladiators, even patriotically motivated participants. For then such cases join sporting events like boxing, football, and other aggressively competitive sports, where the moral magic of consent can make right what would otherwise be wrong.23 These, too, we separately deal with below.

The harder cases are where the combatants had no choice about becoming combatants, and where neither side in the combat can claim the moral high ground. Yet even in these cases we think that the morality is plain, and that it is plainly non-combative. Conscripted gladiators are not obligated to kill one another; nor are they obligated to defend themselves. Conscripted soldiers are no different, no matter how much the rhetoric of the law of war may pretend otherwise. So no strong or mixed moral combat.

But (and still holding self-defense rights in abeyance for now) neither are such gladiators/soldiers permitted to kill one another. Wars where neither side is justified in fighting them are like gladiatorial contests where the fighting is done for insufficient reason; no one is permitted to engage in such unjustified violence, however much it may be understandable and even excusable if one succumbs to state coercion and fights anyway (recall the French firing squads of World War I). So no weak moral combat is to be found here either.

B. The Supposed Cases where one has a Right to do Wrong

It is not obvious to us why such “right-to-do-wrong” cases get mentioned in the context of moral combat. For as usually presented, such cases present instances of conflict of obligation for one person, not moral combat between two people. Take the two level view of abortion:24 first level, it is wrong for the woman to abort; second level, it is permitted nonetheless for women to abort. The problem prima facie is one of contradiction about the woman’s obligations, not moral combat: if she is permitted to abort, then it is not the case that she is obligated not to abort; yet if abortion is wrong, she is obligated not to abort.

What this analysis shows is that there is no literal right to do wrong under even the most minimalist deontic logic. What people have to mean instead when they say this is: first level, women are obligated not to abort (and this makes it wrong to do so); yet there is a more stringent obligation on the part of others not to prevent a woman from aborting her own fetus (making it more wrong for those others to prevent a woman’s choice than it would have been wrong of her to make the choice to abort). This we take to be the standard interpretation of so-called rights to do wrong.25

C. The Supposed Cases of Stained Permissions

We have had colleagues (not all of them Quakers), who hold a softer view of the supposed cases of a “right to do wrong”: on this softer view, one is permitted to defend oneself against a culpable aggressor, and yet the permission is “stained” in the sense that it would be better if it were not exercised. On this view, there is something to be regretted about all killings, even killings one has a right to do as in self-defense. And this moral untowardness is then thought to license others to help us do the better thing by preventing us from defending ourselves. Weak moral combat?26

Yet this is not a plausible moral view, so no logic of rights need be adjusted to accommodate it. In the first place, there are no such things as stained permissions. One is entitled to kill an aggressor who is culpably trying to kill you, full stop, with no regrets or apologies. Second, if there were any staining here, it would be an aretaic staining of one’s virtuous character; and thus irrelevant in a deontic logic such as the logic of rights. Third, the move from “stained-for- actor-X” to “permission-of-Y-to-prevent” is unjustified. If my character is stained by my saving my life in self-defense, what would justify you in having the right to get me killed so that I could die with an unstained character?

D. Regular Cases of Self-Defense, Aggressor-Resistancet o Self-Defense, Third Party Prevention of Self-Defense

In sympathetic expositions of Hohfeld (e. g., Walter Wheeler Cook27), self-defense is often used to illustrate the need for the Hohfeldian concept of a privilege. It is our contention that the notion of a protected permission is a better articulation of the “right of self-defense”, because it (unlike Hohfeldian privilege) rules out the possibility of moral combat -which is good because there is none in typical self-defense situations (we shall deal with less typical cases of self-defense later).

In stage one of typical self-defense situations, it is easy to see that no room need be made to accommodate moral combat; because although there is combat, there is no moral combat. Aggressor is obligated not to attack; defendant is permitted to prevent aggressor’s attack upon her. No moral combat there.

In stage two, aggressor resists the self-defensive force of the defendant. Yet this too does not present a situation of moral combat. Defendant is permitted to use force to ward off aggressor’s attack; and aggressor is not permitted to resist the use of that force by defendant -indeed, he is obligated not to use such force. No moral combat there either.

In stage three, intervenor joins the fray. Yet intervenor is permitted (in some cases, obligated) to use force to aid defender; obligated not to aid aggressor in aggressor’s initial use of force or in his prevention of defender’s preventative efforts. Again, no moral combat in sight here.

E. Innocent Aggressor, Innocent Threat, Innocent Shield, Innocent Side-Effect, Self-Defense Cases

(1) We earlier deferred consideration of the self-defense relations of conscripted soldiers, enslaved gladiators, and the like. We now need to address those issues. Such cases are instances of what are commonly called innocent aggressor cases, cases where the aggressor is innocent because excused (in these last cases, by coercion). Other versions are where: a child, retarded, insane, or otherwise incompetent person threatens you and you use force to prevent such innocent attack. Or: an actor ignorant that the gun he is using has real rather than blank bullets is about to shoot you and you use force to prevent such innocent aggression. The ignorance/incompetence excuses, like the excuse of coercion, makes the aggressor innocent.

(2) Innocent aggressor cases, despite their variations inter se, are but a species of a larger genus. For there are also innocent threat cases and innocent shield cases. Bob Nozick created the (perhaps too fanciful but now nonetheless classic) example of the falling fat man (“FFM”): FFM has been pushed into a well and will crush you if he falls on you, trapped as you are at the bottom of the well; fortunately, you have your trusty disintegrator ray gun which you use to disintegrate the threat, and thus save yourself.28

(3) Innocent shield cases are different yet again. Like innocent threat cases, you do nothing; unlike those cases, the innocent shield does not himself present a threat to you. Yet behind the shield is a culpable aggressor who means to kill you; you can only stop him by shooting through the innocent shield, killing both him and the culpable aggressor.

(4) The innocent side-effect cases are different yet again. Again a culpable aggressor means to shoot you, and again you must shoot him to prevent it. Yet the large caliber gun you are using will inevitably pass its bullet through the aggressor, killing the innocent person behind him, as you knew it would.

The first stage of these four cases all present no difficulty for those denying the existence of moral combat. (1) Excused aggressors (the innocent aggressor cases), ought not to aggress against you, so you being permitted to prevent this presents no instance of moral combat. (2) Y was obligated not to push the fat guy into the well so as to fall on you, so you being permitted to disintegrate the fat guy with your ray gun involves no moral combat with Y. (3) Likewise, the shooter behind the shield is obligated not to shoot you. So your permission to shoot him to prevent it involves no moral combat with him. (4) Ditto on you vis-à-vis the culpable aggressor who you shoot even when an innocent other is behind him.

It is at the second stage of these kinds of cases where things are supposed to get dicier. The second stage is reached when we suppose that the innocent aggressor in (1), the innocent threat in (2), the innocent shield in (3), and the innocent sideffect in (4), all possess the means of their own defense; they can kill X and the hard question is whether they are permitted to do so. If so -and if X is permitted to try to kill them- then we have four cases of weak moral combat.

Nozick raised this second stage of the analysis, but said that he would “tiptoe around these incredibly difficult issues” without resolving them.29 Nozick is right: these are not easy cases, and the present authors will not pretend that even between just the two of them, there is agreement as to how such cases should come out.30 Here is what each of us has previously committed to in print about such cases.

(1) Innocent aggressors

Hurd: The would-be victim of the innocent aggressor, X, is not permitted to shoot the innocent aggressor, Y (although X may be excused); so even if Y is permitted to prevent X’s self-defensive force directed against Y, there is no moral combat here (because Y is in the right).31

Moore: Because Y is the disturber of the status quo by his actions (even though innocent), X does have a permission to kill Y to save X’s own life, and Y has no permission to prevent it. Again, no moral combat (although this time, this is because X is in the right).32

(2) Innocent threats

Hurd: Again, X has no permission to disintegrate Y, although he may be excused if he does so; so again, irrespective of whether Y has a permission to prevent X’s use of X’s ray gun, there is no moral combat.33

Moore: Unlike innocent aggressor cases, innocent threateners did not by their action disturb the status quo with their actions; so X has no exception to his obligation not to kill innocents, and thus, has no permission to disintegrate Y with X’s ray gun; by the same token, Y will have a permission to prevent his disintegration by killing X; so there is no weak moral combat.34

(3) Innocent shields

Hurd: Although X has a permission as against the culpable aggressor Y to shoot Y, X has no such permission as against Z to shoot Y through Z, the innocent shield. So irrespective of Z’s permission to prevent X’s shooting, there is no moral combat.

Moore: Same as innocent threat cases, because the shield is as passive as is the innocent threatener; X is not permitted to kill Z the shield, and Z is permitted to prevent that. So again, no weak moral combat.

(4) Innocent side-effect

Hurd: Still rejects there being any permission of X to kill Z even though (arguably) X’s killing of Z would not be intended but only foreseen. Still no moral combat.35

Moore: Unlike what Hurd believes,36 intentions matter to the scope of our deontological obligations.37 However, either because of the closeness doctrine (if you intend A, and if B is “close” to A, you intend B), or because of the “know-to-a-certainty” doctrine (you are categorically forbidden to cause with epistemic certainty as much as to cause intentionally), this is not a case outside the scope of the obligation not to kill innocents. So again, X has no permission to shoot Z by shooting through Y, and even though Z may prevent such shooting, there is no moral combat.

F. Two Mothers on a Plank (Again)

Since Cicero, discussions of necessity have often begun with two shipwrecked sailors competing for a plank that can only support one of them. To transform this from being (a seeming instance of) weak to strong moral combat, we earlier adopted the variation where it is two mothers who are competing for the plank, not for themselves, but in order to save their child (which by hypothesis they are obligated to do). This admittedly has the appearance of a case of strong moral combat, for what one mother is obligated to do (place her child on the plank) the other is obligated to prevent her from doing, and vice-versa.

A popular solution to plank-like competitions for life-saving resources is to treat them as state of nature cases where no moral obligations or protected permissions bear on what actors do; there is only an absence of obligation (a Hohfeldian privilege) and an absence of a right that the other not compete. Thus, Sir Francis Bacon urged that such cases were governed only by the “law of nature” and not the laws that govern persons,38 and Bernard Williams more recently urged that such cases are beyond morality so that there is no question of obligation or permission.39

While we think that ultimately this is right about certain variations of these cases, it takes us a lot longer to get there than it did Bacon.

Start with the thought that each mother has a stringent duty to rescue her child, and how implausible it is to think that that duty evaporates in the presence of another, equally strong duty on the part of another. So morality does apply, at least initially, and the trick is to see how it applies in a way that does not create moral combat.

Imagine three actions each mother might contemplate:

A1 = |

Place her own child on the plank. |

A2 = |

Push the other child off the plank. |

A3 = |

Hold the other child’s head under water, drowning the child so as to force it to let go of the plank. |

Each mother might well also contemplate the three corresponding preventative actions:

B1 = |

Prevent the other mother from placing her child upon the plank. |

B2 = |

Prevent the other mother from pushing one’s own child off the plank. |

B3 = |

Prevent the other mother from drowning one’s own child. |

If each mother has obligations A1-A3 and B1-B3 then we have three instances of strong moral combat.

The resolution of such cases seems to us to be relatively straight- forward in those versions of them where one child has already been placed on the plank and the second mother seeks to place her child on the plank as well. For these are just ordinary culpable aggressor cases: the second mother cannot save her child by placing it on the already occupied plank -she can only drown the first child along with her own by such an action. She therefore has no good reason (and thus, no obligation or permission) to place her child on the plank (she has at most an excuse), and the mother of the first child is permitted to prevent her from doing so.

If the second child nonetheless makes it on to the plank (which is now sinking), the first mother now has to face the fact that the second child may have achieved the status of being an innocent aggressor -if he placed himself upon the plank; or at least helped his mother do so. And if this is the case, then (at least according to one of us, Moore) the first mother is permitted to throw him from the plank and he is not permitted to prevent her from doing so. On the other hand, if the second child was completely passive with respect to his placement on the plank -it was entirely his mother’s doing- then that second child is an innocent threat or an innocent shield: it is his very presence that stands in the way of the survival of the first child. So seemingly (we qualify this later), as against the innocent second child, the first mother is not permitted to throw it off, nor is she permitted to drown that child. (Generally parents are not justified in killing other children in order to save their own, and thus the seeming moral conclusion above; the first mother is by contrast permitted to prevent the earlier placing of the second child on the plank because that prevention of a preventer of death (a “double prevention” in the trade) is an allowing of death, not a causing of death).

Things get (even?) less clear when both mothers reach the plank at the same time and both simultaneously place their children on the plank. Now neither mother is an aggressor against the other, not culpably and not innocently. Each are permitted and obligated to place their child on the plank. And now, vis-à-vis each other, seemingly neither is permitted to throw the other’s child off (let alone drown it), and both are permitted to prevent the other doing so. So still no moral combat.

As is often recognized, the resolutions thus far of the two infants on a plank case will result in the death of both infants if each mother does what she is obligated to do. Put more strongly, morality seemingly requires both infants to die. Benjamin Cardozo recognized this unhappy consequence of obligating each person in a lifeboat not to throw anyone else overboard, but comforted himself with the thought that perhaps some would voluntarily sacrifice themselves to save the rest:

There is no rule of human jettison. Men there will often be who, when told that their going will be the salvation of the remnant, will choose the nobler part and make the plunge into the waters. In that supreme moment, the darkness for them will be illumined by the thought that those behind will ride to safety. If none of such mold are to be found aboard the boat, or too few to save the others, the human freight must be left to meet the chances of the waters.40

No such comfort as might be afforded by the possibility of self-sacrifice is available in the present situation; for each mother is obligated to save her child, i. e., not to volunteer that child for sacrifice.

Did we conclude too quickly that at t1 each mother is obligated not to thwart the other mother’s placement of her child on the plank, and that at t2 each mother is obligated not to throw the other mother’s child off the sinking plank? After all, there is what we have else-where called the “already dead” (or “mere acceleration”) exception to our duties not to kill innocents.41 When good consequences are in the offing, we have argued that: one may shoot down an airplane headed to the capital (because the occupants of the plane will die soon anyway even if the plane is not shot down); one may separate Siamese twins and give the shared organs to one only (thus killing the other), when without the separation the one who is killed will die soon anyway; mountain climbers may cut the rope on which the life of other climbers depend, if otherwise the weight of the down-rope climbers will drag all down the cliff; one may kill and eat the weakest of a lifeboat filled with four persons, when the alternative of not eating the one is that he too will die along with the other three.

Given this exception, one might argue that each mother is not obligated not to prevent the saving of or not to kill, the other’s child. For if both infants stay on the plank that non-saved or killed child is dead anyway, just a little bit later. Yet notice this isn’t as obviously true in this version of the plank case; neither child is “already dead” -after all, the other might be the one to die. There is, in other words, no inevitability in the victim’s death as there is in the earlier cases cited (where the passengers on the plane are dead no matter what, the twin who dies could not survive even with separation, the down-rope climbers are dead no matter what, and the cabin boy who is killed and eaten was too weak to survive even if another were killed to save him).

The plank case is more like the choice given the mother of two children by the Nazi officer in the film, Sophie’s Choice: neither child is inevitably dead -the tragedy of the film is that who dies depends on Sophie’s choice. (Analogous cases are the lifeboat case where no one is already too weak to survive, no matter what, and the Siamese twins case, where either twin (but only one) could be saved.)

Despite this difference, our own view is that the “already dead” exception does apply to these last, “Sophie’s Choice” variations of the acceleration cases. In which case: while each mother is initially obligated not to thwart the other’s attempts to place her child on the plank, each is obligated not to throw the other’s child off the plank only so long as it is not yet clear that the other mother will not yield and both children will thus sink. When it is clear that neither mother will yield and both children are about to drown, each mother’s obligations (to save and not to thwart) cease and they are nakedly at liberty to throw off the other child, to thwart a like attempt to throw off their own child, and to resist any like attempt to thwart, exerted by the other mother. Such a moral state of nature with its warring, Hohfeldian, naked liberties may yet result in the deaths of both infants if the two mothers cannot work out some form of accommodation, but at least morality through its ban of moral combat does not require that no such accommodation be reached and that both infants must therefore die.

Thus, at the later time when drowning of both infants is imminent, there is no moral combat, and Hurd’s logic (ruling it out) is secure in such cases. But if it should happen at that later time that one child is truly “already dead” -i. e., in such weakened condition as not to survive even if placed upon the plank- then the other mother is both permitted and obligated to throw it off, and the weakened child’s mother is obligated to let the first mother do so. So still no moral combat even though not in a moral state of nature.

G. Sporting Contests and the Creation of Moral Combat by the Exercise of Normative Powers

One of the examples of moral combat that is most commonly offered up is that of competitive sports. One boxer throws a punch, the other prevents the blow; one football player tries to knock another to the ground, and that other prevents the tackle by stiff-arming the would-be tackler. Unless making these moves in these sports is not permitted, we seem to have many sporting instances of moral combat.

Yet sports are consented-to activities by those who participate in them. That is what makes morally permissible actions that otherwise would be morally forbidden. It is not that people through the exercise of such normative powers can artificially create moral combat. It is rather that people through the exercise of their normative powers can release the obligations and confer the rights which (unreleased or unconferred) could have created moral combat. Given that there is such a thing as the “moral magic of consent” -magic that can transform trespass into a social visit and rape into love-making-42 then that magic can strip actual combat of the moral valences (of obligations or of rights) that would make such combat be an instance of moral combat.

Is the existence of this kind of “artificially-created moral state of nature” a problem? We don’t see why. As one of us has said, this “would seem to constitute the exception that proves the rule”.43 If one can artificially create such moral states of nature, that should not lead one to think that there can be moral combat after all. Prior to consent doing its moral magic there is no moral combat because each party’s rights and obligations are intact in the non-combative form that we have charted; after such consent is given the normative powers so exercised also guarantee that there is no moral combat because such combat is impossible in a moral state of nature, no matter whether that state of nature is natural or artificially created by consent.

III. Constructing a Logic for Morality that Has the Potential to Rule Out Moral Combat as a Possibility

Our reading of the literature on moral rights in contemporary philosophy is that the analysis of the logic of such rights is dominated by the work of the legal theorist, Wesley Hohfeld.44 Yet the central insight that made Hohfeld’s analysis so influential was an insight based on the view that moral combat is not only possible but is sufficiently common that it must be accommodated within any logic of rights. Hohfeld’s central insight was to construe active rights as mere Hohfeldian privileges, the correlative of which were not Kant’s duties of non-interference but only the absence of passive rights on the part of others that the right holder not do what he has an active right to do. This insight of Hohfeld was motivated by the thought that often one could have an active right to do an action that others equally had an active right to prevent. Thus was born the weak analysis of an active right as a mere Hohfeldian privilege.

The Hohfeldian system is well worked out and is indeed, elegant in its systematicity. If one interprets the above seven situations of actual combat as we do, and thus has no need to make room for the possibility of moral combat, can one develop an alternative logic that can rival Hohfeld’s in its systematicity? What we seek to do in this, the second half of this paper, is to develop such an alternative logic.

In Moral Combat one of us (Hurd) sought to rule out moral combat by urging that morality contains what Hurd dubbed, “the correspondence thesis”. Hurd:

The correspondence thesis asserts a moral claim about the justification of codependent actions. It holds that the justifiability of an action determines the justifiability of permitting or preventing that action... The correspondence thesis rests on the intuition that, since an action cannot be simultaneously right and wrong, it cannot be the case that one actor may be justified in performing an act while another may be simultaneously justified in preventing that act.45

The thesis is a metaphysical thesis about right actions. It is not an epistemological thesis about the justifiability of a rational agent believing some action to be right. “Justifiability” as used in the quote from Hurd above is thus not a matter of the reasonableness of an actor’s beliefs about the rightness of his actions. Justifiability as here used refers to the rightness of actions itself. (This clarification is needed to forestall any epistemic interpretation of the correspondence thesis; for conflict between what it is reasonable to believe for different people in different epistemic situations is far too common to be ruled out).

The linch-pin of the correspondence thesis is the idea of codependent actions. Codependent actions are casually described by Hurd in various ways in her book: they are actions that thwart other actions,46 actions that intervene to prevent other actions,47 actions that are contradictory,48 acts that punish other actions,49 actions that morally condemn as wrong other actions,50 and actions that permit other actions.51 For the present discussion, focus just on action/prevention pairs; stipulate that two actions A, B are codependent if and only if B prevents A from being done, or A prevents B from being done, or both.52

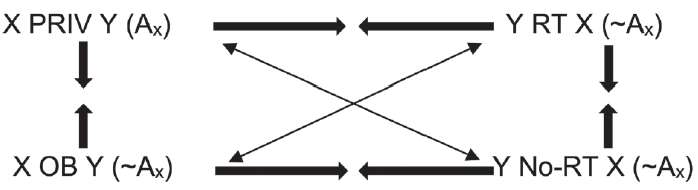

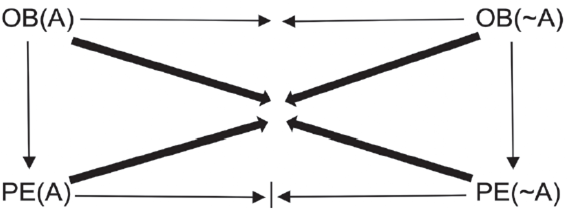

Co-dependency so restricted allows us to formulate the central claims for a logic of rights that is alternative to Hohfelds and that rules out moral combat. The standard analysis of active rights that began with Hohfeld makes two claims. First, it identifies active rights as permissions, as permissions are defined in standard deontic logic; this means that the “opposite” (Hohfeld’s term) of a permission to do A is the presence of a duty not to do A. Second, in addition to relations of opposition, rights have relations of correlativity. For Hohfeld, the correlative of X having a right as against Y to do A is the absence of a right in Y that X not do A.

These relations of opposition and correlation are neatly summarized in a “Hohfeld box”.53 Using the Hohfeldian terminology, in which active rights are called “privileges” and passive rights are called “claim-rights” (or even more simply, “rights”) the box is:

One can eliminate the relations of contradicition (Hohfelds relations of opposition) by negating the upper right and lower left corners of the box. The Hohfeld box then looks like:

The analysis of rights which we defend can also be represented in this box-like fashion. We retain the Hohfeldian identification of active rights with permissions as permissions are defined in standard deontic logic. But we merge into our usage of “permission” what Hohfeldians reserve to claim-rights, namely, the correlative that others have a duty not to prevent what one is permitted to do. Hurd:

I am taking permissions to be distinct from what Wesley Hohfeld called “privileges” or “liberties”. Hohfeld maintained that it is important to keep “the conception of a right (or claim) and the conception of a privilege distinct”... I am concerned with the more common understanding of permissions as rights. Under this conception, permissions count as a combination of both Hohfeldian claim rights and Hohfeldian privileges.54

In this gluing back together of what Hohfeldians would put asunder in the analysis of rights, Hurd is in the good company of Kant,55 Hillel Steiner,56 John Kleinig,57 and many others.

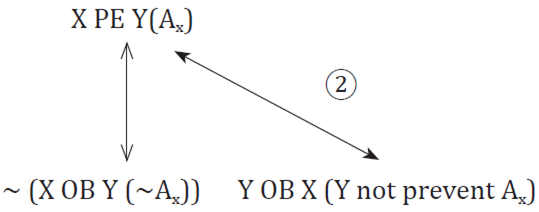

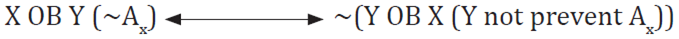

If we were to substitute Hurd’s “protected permissions” operator (“PE”)58 for Hohfeld’s “privilege” operator, the box of correlative and opposite implications we did before for the analysis of active rights would be built in the following steps. Suppose X has a right as against Y that X speak here and now (“Ax “). Conceptualizing rights to do things -active rights- as protected permissions yields:x

a. X PE Y (Ax)

b. The “opposite” (i. e., contradictory) of that would be (bystandard deontic logic): X OB Y (~A )

-

c. Negating that opposite yields an equivalence relation (①):

-

d. Hurd’s version of the correlativity thesis adds another equivalence (②):

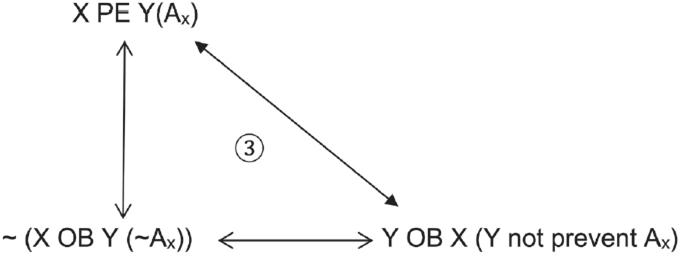

-

e. These two equivalences yield a third (③):

-

f. The correlative itself has an opposite:

-

g. Because of standard deontic logic’s square of opposition, this is equivalent to:

-

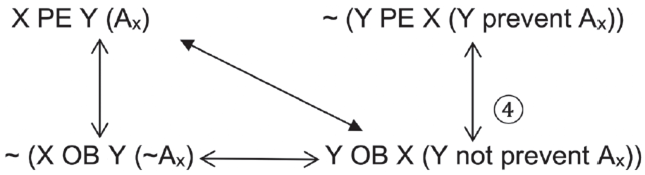

h. Negating this yields a fourth equivalence (④)

-

i. Which yields the fifth (⑤) and sixth equivalence (⑥) to complete the box:

It remains to be shown formally how Hurd’s system does not countenance the possibility of moral combat, as does Hohfeld’s. Recall that there are three kinds of moral combat, strong, weak, and mixed. Let us consider each separately, starting with weak moral combat.

Weak moral combat exists when one party, X, has a permission to do something (“A”) and yet another party, Y, has a permission to prevent X from doing A. Relationship ⑤ above -the relationship between the dominant position and the opposite of the correlative- by its terms rules out any such moral combat when permissions are taken as protected permissions. For ⑤ holds that if X is permitted as against Y to A, then it is not the case that Y is permitted as against X that Y prevent X from doing A.

Next consider strong moral combat. A situation of strong moral combat would exist when X was obligated to do some action A and Y was obligated to prevent X from doing A. Our earlier seeming example of strong moral combat was that of two mothers each being obligated to place their own child on a plank that can only support one and equally obligated to prevent the other from doing likewise.

Again, let X be the first mother. X is obligated vis-à-vis Y that X place X’s child on the plank (“Ax”). Let Y be the second mother. If Y is obligated to prevent X from placing X’s child on the plank so that she

(Y) can place her own child on the plank (“Y prevent Ax”), this would instantiate the requirements of strong moral combat:

X OB Y (Ax), and Y OB X (Y prevent Ax)

Yet Hurd’s logic rules out this as a moral possibility. The formal proof is:

| 1. X OB Y (Ax) | (Premise) |

| 2. If X OB Y (Ax), then X PE Y (Ax) | (standard deontic logic) |

| 3. X PE Y (Ax) | (1, 2, M.P.) |

| 4. If X PE Y (Ax) then Y OB X (Y not prevent Ax) | (Hurd’s correlative relation ② for protected permissions) |

| 5. Y OB X (Y not prevent Ax) | (3, 4, M.P.) |

| 6. ~[Y OB X (Y not prevent Ax) and Y OB X (Y prevent Ax)] | (standard deontic logic, no conflict of duties) |

| 7. ~Y OB X (Y not prevent Ax) or ~Y OB X (Y prevent Ax) | (6, De Morgan’s Laws) |

| 8. ~Y OB X (Y prevent Ax) | (5, 7, disjunctive syll. plus doublex negation) |

| 9. If X OB Y (Ax), then ~Y OB X (Y prevent Ax) | (1-9, natural deduction) |

Lastly, consider situations of mixed moral combat, situations, where either: (1) one party is obligated to A and the other is permitted to prevent the first party from A-ing; or (2) where one party is permitted to A and the other is obligated to prevent the first party from A-ing. Take the second of these (for ease of illustration in light of what was done with strong moral combat). When X is permitted as against Y to do action A, then steps 3-8 in the deduction done for strong moral combat can be repeated here, resulting in the conclusion:

8. ~Y OB X (Y prevent Ax)

Steps 3-8 then (by natural deduction) yields a new conclusion:

If X PE Y (Ax), then ~Y OB X (Y prevent Ax)

Which rules out case (2) of mixed moral combat.

Hohfeld, by contrast, permits moral combat and, indeed, celebrates its possibility. Hohfeld’s much touted distinctions between claim-rights and privileges, and the restrictions of commonly described rights to do things to mere privileges, were designed precisely to allow for situations of moral combat, both weak and strong. Yet despite the enormous comparative advantage to Hurd’s logic of co-dependent actions, there are several worries one might have about the system.

One worry about the systematcity of a scheme built on there being “co-dependent actions” stems from the relations of content Hurd posits to exist between the contents of her correlative rights and duties. The correlative she posits is: if X RT Y (X do A), then Y OB X (Y not prevent (X do A)). It is instructive to compare Hurd’s content-relation between action/prevention-of-action pairs, with the content relations in Hohfeld’s two correlativity claims. Between the contents of claim-rights and correlative duties, the subject of Hohfeld’s correlativity thesis for passive rights, Hohfeldians proudly point out that their common content is “one and the same action”.59 If X has a right that Y not go on X’s land (a passive right), then Y has a correlative duty that Y not go on X’s land. Such identity of content is not to be expected between the contents of privileges and their correlativity-related absence of rights, the subject of Hohfeld’s correlativity thesis for active rights. But Hohfeldians can at least claim for privileges that the contents of the correlatives are “logically related”:60 a privilege of X as against Y that X do A, is correlated with an absence of a claim right by Y as against X that X not do A, which correlative itself requires an absence of a duty by X to Y that X not do A. So long as “not” in such content shifts (across correlatives and opposites) denotes the logical connective of negation, this too, it is said, comports with the requirements of the Hohfeldian scheme being one of “logic”.

Yet are the Hurdian content connections any less systematic and “logical?” In the Hurdian logic the correlative of X’s permission (that X do A) is a duty on the part of Y (that Y not prevent X do A). The “X do A” part of the content seems to be identical as those contents are phrased; yet this is an illusion. Preventions are inherently negative: to prevent something is to cause its non-existence.61 So really the Hurdian correlative of a permission of X as against Y for X to do A is a duty on Y not to cause it to be the case that X does not do A. Not identity, but still the logical relation of negation -except for the “cause it to be the case” bit, a bit that has no analogue in the content of X’s correlative permission.

Before concluding that this is a big difference in the logical character of the content relations of a Hurdian as opposed to a Hohfeldian logic, consider more carefully the nature of the content relations between an obligation (or a privilege) to do A and an obligation to omit to do A.62 Action language such as, “X did A” (on what is now a pretty standard analysis, “the causal theory of action”63), can be paraphrased into, “X caused state of affairs a to exist” (where “a” refers to a token of the type of action described as “A”), and, on versions of the causal theory of action such as Moore’s, that in turn can be paraphrased into, “X’s willing caused a to exist”.64 These paraphrases capture the crucial fact about actions, which is that they are the bringing about of some state of affairs by a person. Now contrast omissions. Although generically these are simply absent actions (or “not-doings”),65 the subclass of omissions for which we can be held responsible -i. e., the omissions about which we have obligations- these too, like actions, require involvement of the agency of the person who omits. In our view, there is no possibility of there being culpable omissions that are merely inadvertent rather than willed;66 such agential involvement thus requires a willing of an absence by the omitter. Thus, “X omits to do A”, can be paraphrased as, “X’s willing caused an absence of state of affairs A”.67

Now one can see the content relations presupposed by Hurd in its true light: there is indeed a shift from the content of a permission that X do A to an obligation that Y not prevent X do A, namely, a shift to, “Y not cause X not to do A”. But there is also a shift for Hohfeldians from the content of a privilege that X do A, first, to the correlative absence of a right for Y that X not do A, and second, to the negated opposite, which is, the absence of a duty by X that X prevent himself from doing A, the content of which in turn is just, “X not cause X not to do A”. The Hurdian shift in content requires a shift in agents whereas the Hohfeldian shift does not; but that is it. The moment that agential involvement is made explicit in the deontic logic of actions and omissions, the comparative shifts in content between the two schemes can be seen in this minimally differing way.68

Another worry about a logic of co-dependent actions stems from the seeming vagueness/exception ridden nature of the notion of a prevention. Even when co-dependency is limited to preventions rather than some broader notion, such as Kant’s interference, it is still the case that some preventions are not prohibited even as the action prevented is one the actor had a right to do. For example, although X may have a right to speak on a particular occasion, others may be under no duty not to prevent his speaking if they do so in certain ways rather than others -such as not loaning the speaker the automobile he needs to get to where he is to speak, etc. This is supposed to show that preventions as such cannot be the content of a duty correlative to the right of another to do the action prevented. Yet in these respects “prevention” differs little if at all from other actions that are accurately described nonetheless as being prohibited by morality even though there are many exceptions where doing such actions is permissible. Killing, for example. We each are generally under a duty not to kill, and yet we may kill to defend ourselves, our family members, or others, as we may kill in fighting a just war, in exacting capital punishment, in law enforcement, etc. Few act types are exceptionlessly prohibited by morality, and prevention is no exception to that truth.

This reminder is the grain of truth we see in Herbert Hart’s well-known view that denies that there is a general duty not to prevent any action that another has a right to do while admitting that there is a “perimeter” of peripheral obligations that make it look like -but only look like- each active right has a correlative duty of non-prevention on the part of others.69 What Hart saw was how many moral norms go into forbidding or permitting the act-types that on occasion can constitute a prevention of some action some actor has a right to do. What Hart didn’t see is how such norms can be seen as fleshing out what are exceptions to a general duty of non-prevention (of rightful action) and not describing piecemeal substitutes that taken together add up to such a general duty. Such norms give content to correlative duties of non-preventions just as they do to correlative duties not to kill.

A third worry for the alternative logic we have here developed stems from its implications for the two-level analysis we did earlier with respect to the so-called “right to do wrong”. Recall that to avoid contradiction the standard interpretation of such rights was that although it was wrong for X to do A, it was more wrong for people to prevent X doing A.

Yet this relatively standard resolution of this conundrum raises a subtle problem for the Hurd logic. Recall that relation ③ in the four-fold Hurd box was:

This is equivalent to:

If abortion is wrong, then the mother, X, is obligated not to do it; yet on the standard solution to the two-level problem above, it is the case that others, Y, are obligated not to prevent her from having an abortion. This contradicts relation ③, the equivalence relation between the negated opposite and the correlative of the Hurd box.

This way of solving the two-level problem about issues like abortion is thus seemingly ruled out by Hurd’s deontic logic. Yet the two level argument solution above sounds right; it is certainly better than the flatly contradictory “right to do wrong”. Yet the argument could be formulated differently so as not to violate Hurd’s logic. Indeed, this is one of the places that Hurdians and Hohfeldians can share the same response, because both can repair to the agent-relative and victim-relative nature of moral obligation that Hohfeld so distinctively defended. The two level solution to the abortion example should be represented like this:

First level: X OB Y (~Ax)

(The mother, X, is obligated to the fetus, Y, not to abort it) Second level: Z OB X (not prevent A )

(Z (i. e., all of us) are obligated to the mother, X, not to prevent X from aborting Y)

These two levels together yield both:

(1) ~X PE Y (A )

(X is not permitted as against the fetus to abort)

and (from the first correlativity relation in the Hurd box)

2. X PE Z (Ax)

(X is permitted as against third parties to abort)

Yet these two statements of permission only look contradictory if one ignores the different persons with respect to whom they are held.70

This response answers the other examples (of obligations not to prevent actions the actor is obligated not to do) proposed by those sympathetic to the Hohfeldian scheme. David Lyons imagines “Alvin” making a speech he is wrong to make (a false and defamatory speech, perhaps); yet Lyons hypothesizes that it would be wrong to prevent Alvin from speaking (presumably on some “no prior restraints” view of the matter).71 Again, however, we have to ask Hohfeld’s question of, “wrong to whom?” Seemingly one should answer in Alvin’s case, “wrong to the person defamed by the speech”. Yet the one(s) who would wrong Alvin by preventing him from speaking is not that person but are third parties, i. e., everyone else -again, Alvin can be permitted to speak (as against all of the rest of humanity) while at the same time being obligated (as against his victim) not to so speak, without there being any hint of a contradiction.

The only place this analysis wouldn’t work would be where the victim (e. g., Alvin’s victim) himself has an obligation not to prevent Alvin from defaming him. Imposing such an obligation on the fetus in the abortion example of course makes no sense; but does it make much more sense to impose it on Alvin’s victim? Why is that victim obligated not to defend himself against wrongful defamation by preventing it? After all, he can defend himself against wrongful violence by preventing it; why not against defamation or other wrongful speech too?

IV. Conclusion

One way to view the relationship between disagreements in belief and disagreements in action is along a motivational dimension. One’s motives to resolve cognitive disagreements surely includes peaceful political accommodation but also includes an epistemic dimension: resolving cognitive disagreements allows us to achieve collectively what we each have the capacity to achieve individually, viz, to know the truth about what morality requires of us.

If what morality required of us was that what some of us are obligated to do, others of us were obligated to undo, it would undermine both the political and the epistemic motives to resolve cognitive disagreements. As to the political dimension, peace would not be forthcoming when cognitive disagreements are resolved because the moral truths so agreed upon would require or permit considerable political strife despite there being cognitive agreement. With respect to the epistemic dimension, one would also be demotivated to learn the truth. This latter demotivating effect of moral combat would be the collective analogue of the demotivating effect conflict of obligations would have on each individual’s motivation to learn the truth. In both cases, our (individual and collective) search for the truth requires a truth worth finding; that there can be no moral success for half of us in situations of moral combat would be a bitter, demotivating truth indeed.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)