Orobanchaceae is the largest family of parasitic plants, containing several nutritional stages (Westwood et al. 2010, Heide-Jørgensen 2013). Holoparasitism is the condition of parasitism where all nutrients are obtained from a host through specialized structures called haustoria (Kuijt 1969, Heide-Jørgensen 2013). It has been suggested that it appeared at least three independent times along the evolution of Orobanchaceae (McNeal et al. 2013, Fu et al. 2017, Mortimer et al. 2022). According to Stevens (2023), the updated diversity of the family consists of 104 genera with 2,309 species. Of these, 20 genera with more than 270 species are holoparasitic (Heide-Jørgensen 2013, Nickrent 2020). Current phylogenetic classification of the family contains eight clades, one of them being Orobancheae, which consists of exclusively holoparasitic species with 15 genera and ca. 230 species (Schneeweiss 2013, Nickrent 2020, Stevens 2023). Orobanche L. is the most diverse genus of this clade, in spite of the transference of some species to the resurrected American genus Aphyllon Mitch. (Schneider 2016). Phylogenetic studies suggested that Aphyllon species had a rapid diversification in the Pleistocene (Schneider & Moore 2017). Also, the species of Aphyllon developed host specificity to one or very few host species along its distribution (Schneider et al. 2016).

The current circumscription of Aphyllon includes two sections based on morphology. Section Aphyllon is defined by the absence of bracteoles subtending the calyx and pedicels longer than the flower; in contrast, section Nothaphyllon A. Gray possesses two bracteoles subtending the calyx and pedicels equal to or shorter than the flower (Schneider 2016). A taxonomic treatment of Mexican Aphyllon species is still needed. Only some of its species (still treated as Orobanche) have been addressed in regional treatments (Calderón de Rzedowski 1998, Alvarado-Cárdenas 2008). The species of the A. cooperi complex in Central and Northern Mexico were studied by Collins & Yatskievych (2015). The latest studies on the genus were the description of A. castilloi Franc.Gut., Cházaro & Espejo (Francisco-Gutiérrez et al. 2019) and the redescription of A. franciscanum (Achey) A.C.Schneid., segregated from A. fasciculatum (Nutt.) Torr. & A. Gray as result of morphometric analyses (Schneider & Benton 2021).

The taxonomic determination of holoparasitic species is complicated due to the nature of the species, whose structures discolor during drying. Herbarium specimens are very similar morphologically and internal characters, which contribute to distinguish among taxa, often cannot be dissected and observed. Platforms and applications of citizen science for uploading photographs of living specimens like iNaturalist, can be useful data sources for taxonomic determination. Based on observations recorded in Chiapas and uploaded to iNaturalist, individuals belonging to the genus Aphyllon were detected. The observations did not correspond in morphology or distribution to any of the Aphyllon species extant in Southeastern Mexico. The subsequent collection of specimens and their detailed analysis corroborated that it is a new species for science. With this additional new species, Aphyllon now comprises 26 species, 22 of them distributed in North America and the remaining four in South America.

Here a new holoparasitic species discovered on iNaturalist is presented. The aims of this study were: 1) to describe and illustrate a new Aphyllon species and 2) compare it with the known species of the genus in Mexico.

Materials and methods

Taxonomic determination. Photographed plants of Aphyllon by user Jonapa on iNaturalist were first visually compared with other species of Aphyllon determined on the platform. As a first complete revision of the specimens of Aphyllon stored in ENCB, IBUG, MEXU, and XAL herbaria (all herbaria acronyms follow Thiers 2023) from 2017 to 2020 did not provide records of species in Chiapas, a second revision of herbarium online databases were performed. Due to absence of specimens from Chiapas in the herbaria examined, a botanical exploration was carried out to locate the plant at the coordinates published on iNaturalist. The collected specimens of Aphyllon were dissected to describe, measure, and photograph morphological characters and color before the plants darkened. Roots of host species are under phylogenetic determination; results of analyses will be published in the forthcoming checklist of Orobanchaceae of Mexico. Species determination was made comparing structures with characters of the taxa reported for Mexico by Francisco-Gutiérrez et al. (2019) and the taxa recently redefined by Schneider & Benton (2021). In this study, we followed the infrageneric classification proposed by Schneider (2016).

Species concept. We followed the concept of species cohesion (Templeton 1989) as an explanatory hypothesis for taxon recognition. The concept has a population genetics framework but does not disregard other cohesive factors to explain species recognition, such as expression of morphology (phenotypic variability constraints on individuals) and habitat distinctiveness (geographic distribution and ecological constraints). All these factors, together with the evolutionary processes, act for the differentiation of the tocogenetic networks into two distinct lineages.

Distribution maps. Taxa from herbarium specimens, and observations of iNaturalist determined by specialists, were georeferenced. Photographs of iNaturalist with open license (CC-BY-NC) were used to illustrate the species. Maps were assembled in QGIS v.2.18.15 (QGIS Development Team 2016) using the digital elevation model provided by Fick & Hijmans (2017).

Results

Aphyllon chiapense Franc.Gut. & L.O. Alvarado, sp. nov. (Figures 1, 2). Type. Mexico, Chiapas, Berriozábal: cerca de la orilla del río El Sabinal, al sur del Libramiento Sur, 16º 45’ 15” N, 93º 17’ 57” W, 934 m, 05 January 2023, A. Francisco-Gutiérrez, V. Pérez-Vázquez & M.E. Gutiérrez-Ramírez 285 (Holotype: MEXU; Isotypes: IBUG, XAL).

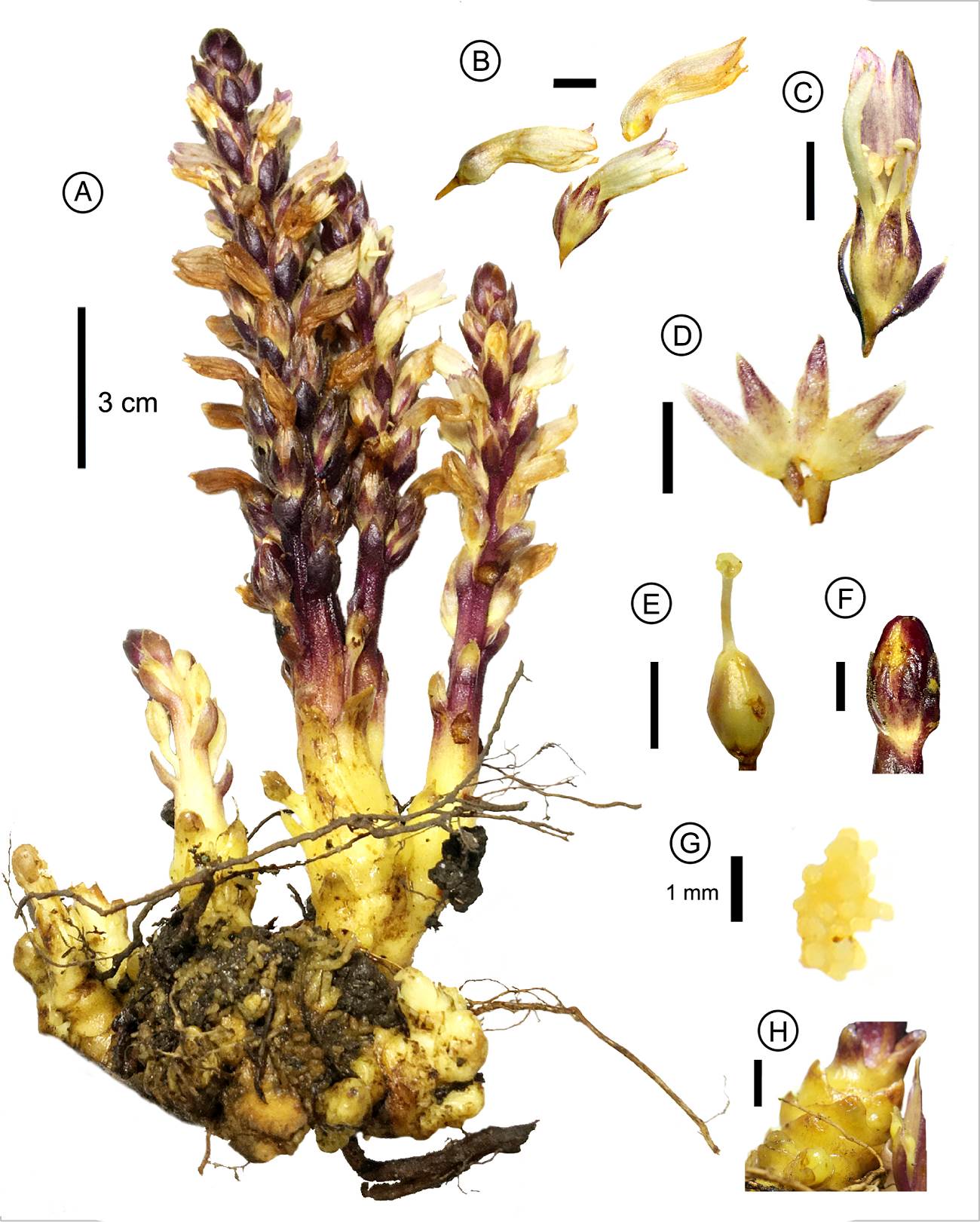

Figure 1 Aphyllon chiapense sp. nov. A) habit, B) corollas with divided lobes of lower lip, C) dissected flower, D) dissected calyx, E) ovary with peltate stigma, F) fruit, G) immature seeds, H) scales. Scale bars represent 5 mm, except for when indicated. All photographs taken by Antonio Francisco-Gutiérrez.

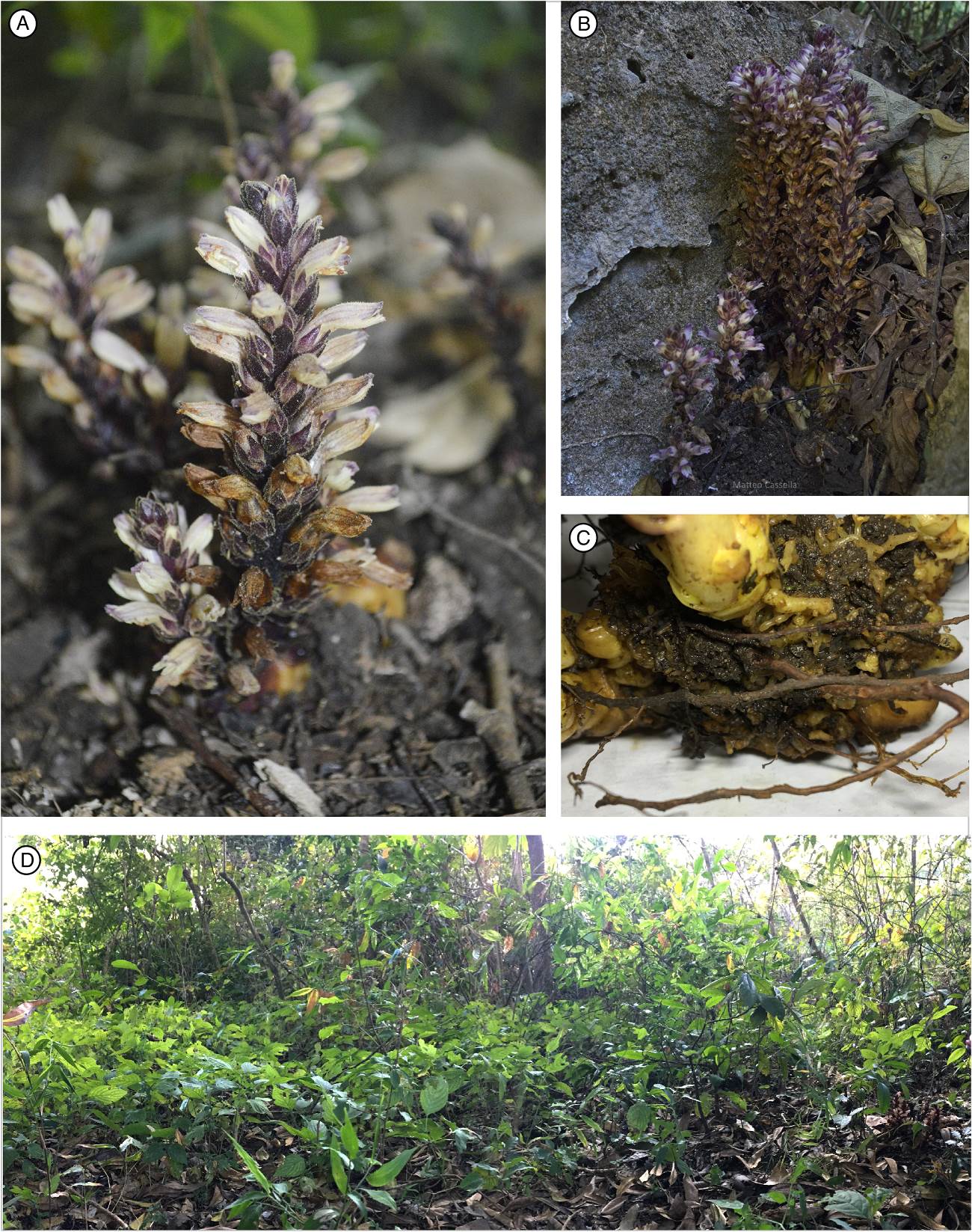

Figure 2 Field photographs of Aphyllon chiapense. A) mature plant, B) tallest known plants, C) host roots embedded in the tubercule of the parasite, D) panoramic view of the tropical rainforest where the new species grows (first from right). Credits: A, Victoria Pérez-Vázquez, B, Matteo Cassella (iNaturalist), C and D, Antonio Francisco-Gutiérrez.

Diagnosis. Aphyllon chiapense belongs to A. sect. Nothaphyllon because of the presence of two bracteoles subtending the calyx, and pedicels shorter than the flowers; this species differs from the rest of the section by its mainly white corolla tube and narrowed to nearly closed corolla mouths, and straight and no revolute lobes of the lower lip .

Description. Achlorophyllous and holoparasitic plant. Thick subterranean tubercles, yellowish to greenish, 3-10 cm wide. Stems fleshy, 10-50 cm tall from above the ground, 4-15 mm wide, solitary or branched at base, glabrous at base to glandular-pubescent along the inflorescence, yellowish at base to dark purple along the inflorescence. Leaves reduced to scales, imbricate, triangular to broadly ovate, 4.7-12 × 3.7-10 mm, apex generally acute, margin entire, fleshy and coriaceous, waxy and glabrous on the surface. Inflorescence raceme occupying almost all the aerial part of the plant, flowers bracteate and pedicellate. Pedicels claviform, 3.6-13.9 × 1.7-3.1 mm, yellowish to purple, glandular-pubescent. Bracts sessile, elliptic to lanceolate, 7.8-10.6 × 2.2-4.4 mm, margin entire, apex obtuse. Bracteoles 2, linear to narrowly linear-lanceolate, 9-16.1 × 1.1-1.8 mm, margin entire, apex acute, externally glandular-pubescent, purple. Calyx campanulate, 7.2-12 × 4-6.5 mm, 5-lobed, lobes triangular, 3.2-5.3 × 1-3 mm, margin entire, apex acute, glandular-pubescent, yellowish with lobes purple. Corolla tubular, 18.4-21 × 2.7-5.7 mm, mainly white on the ventral surface, light purple on dorsal surface, constrained above the ovary and narrowed mouth, apparently closed, glandular-pubescent externally, palatal folds absent, glabrous, white. Upper lip 3.1-5.3 × 5.5 mm, 2-lobed, lobes 4-5.1 × 2.2-2.9 mm, ovate, margin entire, externally light purple, internally purple. Lower lip 3-lobed, lobes 3.2-5.1 × 1.3-2 mm, oblong to linear, straight and non-revolute, margin entire, apex bifid, each lobe 0.56-0.81 × 0.43-0.77 mm, white. Stamens filiform, 7.4-10.5 × 0.3-0.6 mm, glabrous, yellowish. Anthers 0.9-1.6 × 0.3-1.3 mm, glabrous or scarcely covered with simple hairs, base apiculate, included, yellowish, stalked glands on dorsal surface absent. Style 2.2-4.4 × 0.3-0.8 mm, glabrous, yellowish. Stigma laminar discoid ripply, 0.8-1.2 × 1.1-1.7 mm, yellowish. Ovary ovoid, 2.9-5.7 × 1.8-3.7 mm, glabrous, yellowish. Fruit a capsule ovoid to elliptical, 11-13.6 × 5.8-7.6 mm, glabrous, dark purple. Seeds (immature) numerous, irregularly ellipsoid, 0.32-0.35 mm in diameter, yellow, outer layer not distinguishable.

Distribution and ecology. Aphyllon chiapense is only known from two locations from the municipalities of Berriozábal (collected specimens for this study) and Ocozocoautla (citizen science observations) in Northwestern Chiapas, Mexico. The species was found inhabiting tropical rainforest. The plants were found at elevations between 870 and 934 m, ranges obtained during the field work and iNaturalist observations. Species growing together with the new taxon are Cedrela odorata L., Tabebuia rosea (Bertol.) DC., Aspidosperma megalocarpon Müll. Arg., Bursera simaruba (L.) Sarg., Centrosema virginianum (L.) Benth., Ipomoea corymbosa (L.) Roth ex Roem. & Schult., Cirsium mexicanum DC., Senna nicaraguensis (Benth.) H.S. Irwin & Barneby, Dioscorea cyanisticta Donn. Sm., and Amphilophium crucigerum (L.) L.G. Lohmann. The tubercles were observed to be attached to two different kinds of roots which were followed, but their length exceeded one meter, making their tracking difficult. The first known citizen science observation of the species (available at https://www.naturalista.mx/observations/10776255) mentions to Jatropha curcas L. (Euphorbiaceae) as the possible host species, but it was not observed at the type locality. Molecular analyses are under development to identify the host species of multiple seedlings and trees attached to the Aphyllon haustoria.

Conservation status. Aphyllon chiapense is only known from two localities, one revealed from the iNaturalist platform (available at https://www.naturalista.mx/observations/10776255, https://www.naturalista.mx/observations/145552685, https://www.naturalista.mx/observations/146226689) and the other from the botanical exploration. The new species is potentially threatened by the habitat destruction due to the construction of housing in conserved areas of the municipality of Berriozábal, Chiapas. The other locality of the municipality of Ocozocoautla, reported in 2016 on iNaturalist, was visited without finding plants of the new species. The site is most similar to a tropical dry forest, considerably dryer than the locality of Berriozábal where specimens were collected. There is a lack of information related to more populations of the new taxon, so the data is considered insufficient (DD) to assess its conservation status (IUCN 2022).

Phenology. The known flowering season is from December to January. Fruits were collected in January.

Etymology. The epithet honors the state of Chiapas, Mexico, where the species was first observed, determined, and collected.

Taxonomic notes. The genus Aphyllon consists of holoparasitic plants whose morphology, distribution, and interaction with hosts require much work to understand. This contribution provides novelties in the first two aspects. Likewise, with this proposal of new species, Aphyllon now comprises 26 species, 22 of them distributed in North America and the remaining four in South America. Most of the Aphyllon taxa in Mexico belong to section Nothaphyllon: A. tuberosum (A. Gray) A. Gray, A. californicum subsp. feudgei (Munz) A.C. Schneid., A. cooperi A. Gray subsp. cooperi, A. cooperi subsp. latilobum (Munz) A.C. Schneid., A. cooperi subsp. palmeri (Munz) A.C. Schneid., A. dugesii S. Watson, A. parishii (Jeps.) A.C. Schneid. subsp. parishii, A. parishii subsp. brachylobum (Heckard) A.C. Schneid., and A. castilloi; whereas only one species belongs to section Aphyllon, A. fasciculatum (Nutt.) Torr. & A. Gray (Schneider 2016, Francisco-Gutiérrez et al. 2019).

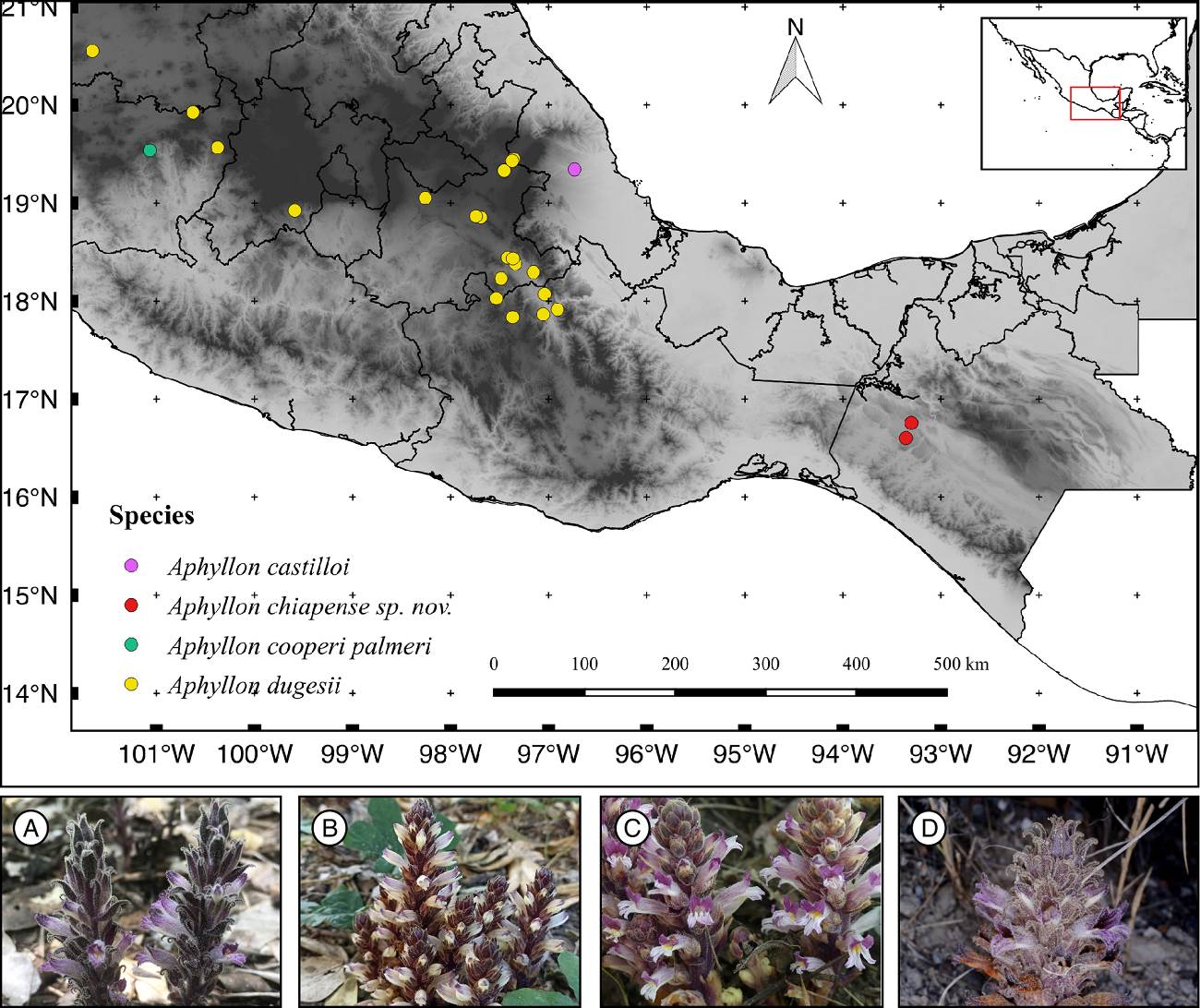

Due to the morphological similarity of the herbarium specimens of the species found in Southern Mexico, we provide a photographic comparison and distribution map to differentiate the taxa inhabiting this area: A. castilloi, A. cooperi var. palmeri, A. dugesii, and the new species A. chiapense (Figure 3). All these species share similarity in having brown to purple and glandular trichomes on bracts and sepals. Also, the corollas have purple colors mainly on the lobes (Figure 3). The most similar species to A. chiapense based on morphology and type of vegetation is A. castilloi, another endemic species restricted to tropical rain forests. Diagnostic characters among these two species are presented in Table 1. The most evident feature of this new species with respect to the other species in the genus, is the corolla mouth nearly closed, with the lobes of the lower lip straight and non-revolute, and the absence of palatal folds, features distinguishable in photographs of living plants available on the citizen science platform iNaturalist and a previous illustrated article (Collins & Yatskievych 2015). These shared attributes among the individuals of the species described here and their differences with those of the taxa compared, fulfill the morphological cohesion (restrictions of phenotypic variability in individuals), proposed in our explanatory hypothesis.

Figure 3 Distribution map of Aphyllon species in Southern Mexico: A) A. castilloi, B) A. chiapense, C) A. cooperi subsp. palmeri, D) A. dugesii. Credits of iNaturalist observers: Antonio Francisco-Gutiérrez (A), Rosa Isela Altúzar-González (B), Leon995 (C), Rocío Ramírez-Barrios (D).

Table 1 Morphological comparison between Aphyllon chiapense sp. nov. and A. castilloi.

| Characters | Aphyllon chiapense | Aphyllon castilloi |

|---|---|---|

| Tubercle width (cm) | 3-10 | 1.5-4 |

| Tubercle color | Yellowish to greenish | Whitish |

| Stem length (cm) | 10-50 | 3.5-13 |

| Stem indument | Glabrous at base to glandular-pubescent towards apex | Pubescent to densely pubescent towards apex |

| Corolla color | Mainly white on the ventral surface, light purple on dorsal surface, lobes light purple externally, purple internally | Purple o light purple, white at base and lobes purple. |

| Lower lobes shape and curvature | Oblong to linear, straight | Oblong to ovate, revolute |

| Palatal folds | Absent | Present |

| Stigma shape | Laminar discoid | Bilobed |

| Capsule length (cm) | 1.1-1.36 | 0.7-1 |

| Altitude (m) | 870-934 | 530-600 |

| Flowering | December-January | October-December |

| Habitat | Tropical rainforest | Semideciduous tropical rainforest |

| Geographic distribution | Chiapas, Mexico | Veracruz, Mexico |

| Source | This study | Francisco-Gutiérrez et al. 2019 |

The discovery of this new species is also relevant due to the fact that the genus Aphyllon was not reported in the state of Chiapas by Francisco-Gutiérrez et al. (2019). The most recent Mexican checklist of native species (Villaseñor 2016) reported the presence of Aphyllon in 23 states, but not in Chiapas. The online database of MEXU herbarium (https://datosabiertos.unam.mx/biodiversidad/) also does not record specimens from Chiapas. Additionally, this is the second known tropical species of Aphyllon. The first one, Aphyllon castilloi, was described from tropical semideciduous forest in central Veracruz, eastern Mexico, a rare type of vegetation for the genus, normally distributed in desertic areas (Francisco-Gutiérrez et al. 2019). However, Aphyllon chiapense inhabits zones with high trees (> 30 m) and high levels of humidity. Additionally, the potential host of A. chiapense must be a completely different species, since the vegetation composition is distinct from that of the other species of the genus in Mexico (Francisco-Gutiérrez et al. 2019). Molecular phylogenetics (Schneider et al. 2016) and morphological observations (Francisco-Gutiérrez et al. 2019, Schneider & Benton 2021) suggested host-specificity of the species of Aphyllon, a pattern observed in other holoparasites (Ortega-González et al. 2020). These contrasting environments in which A. chiapense and A. castilloi grow reflect the differences in habitat and environmental requirements of each of them (habitat distinctiveness) suggested in the cohesive species concept.

Discussion

iNaturalist platform information is increasingly being considered in biological studies, as it complements data present in biological collections and contributes to documenting biodiversity loss and conservation (Spear et al. 2017, Soteropoulos et al. 2021). Likewise, it has been relevant in the rediscovery of taxa and the discovery of new species (Egger & Velázquez-Sánchez 2018, Svoboda & Harris 2018, Alvarado-Cárdenas et al. 2020). In the case of the species of Aphyllon, observations of citizen science can be a useful tool to determine specimens collected or photographed, or as in this case, to identify undescribed taxa, and to have precise data to perform scientific collections and collaborations.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)