The tribe Heliantheae constitutes one of the 43 tribes of the Asteraceae (Compositae) family as it is currently circumscribed (Baldwin 2009). It is considered as part of the “Heliantheae Alliance” along with other 12 tribes, although their relationships remain in discussion. Taxonomically this tribe has been divided in seven subtribes, including the Helianthinae, which comprises Viguiera and another 19 genera (Table 1). Viguiera was established by Kunth (Nov. Gen. Sp., ed. Fol., 4: 176. 1818) describing one species (Viguiera helianthoides). In 1918 Blake presented the first monograph of the genus, including about 141 species (Blake 1918). Since then, many new species have been added to the genus, reaching up to 270 species distributed from the southwestern United States of America to Argentina in South America.

Table 1 Genera included in the Subtribe Helianthinae (Tribe Heliantheae) of the family Asteraceae. An asterisk indicates the monophyletic genera derived from the new classification of the genus Viguiera. Abbreviations: CAME= Central America, MEX= Mexico, SAME= South America, USA= United States of America)

| Genera | Total species | Distribution |

|---|---|---|

| *Aldama La Llave, 1824 | 123 | SW USA to SAME |

| *Bahiopsis Kellogg, 1863 | 11 | SW USA to MEX |

| *Calanticaria (B.L. Rob. & Greenm.) E.E. Schill. & Panero, 2002 | 5 | MEX |

| *Davilanthus E.E. Schill. & Panero, 2010 | 7 | MEX |

| *Dendroviguiera E.E. Schill. & Panero, 2011 | 15 | MEX to CAME |

| *Gonzalezia E.E. Schill. & Panero, 2011 | 3 | MEX |

| *Heiseria E.E. Schill. & Panero, 2011 | 3 | SAME |

| *Heliomeris Nutt., 1848 | 6 | NAME to MEX |

| *Hymenostephium Benth., 1873 | 22 | MEX to SAMEr |

| Iostephane Benth., 1873 | 4 | MEX |

| Lagacea Cav., 1803 | 9 | SW USA to SAME |

| Pappobolus S.F. Blake, 1916 | 37 | SAME |

| Phoebanthus S.F. Blake, 1916 | 2 | USA |

| Scalesia Arn., 1836 | 15 | Galapagos Islands |

| Sclerocarpus Jacq., 1784 | 9 | SW USA to SME, Old World |

| *Sidneya E.E. Schill. & Panero, 2011 | 2 | SW USA to MEX |

| Simsia Pers., 1807 | 29 | SW USA to SAME |

| Syncretocarpus S.F. Blake, 1916 | 3 | SAME |

| Tithonia Desf. ex Juss., 1789 | 12 | SW USA to CAME |

| Viguiera Kunth, 1818 | 19 | SW USA to SAME |

Schilling & Panero (2002, 2011) studied the subtribe Helianthinae based on molecular sequences of nuclear ITS, ETS, and cpDNA, stating that the genus Viguiera Kunth, as traditionally conceived, does not constitute a monophyletic group. Among their conclusions they propose to reclassify the genus, relocating its species in at least other nine genera: Aldama La Llave, Bahiopsis Kellogg, Calanticaria (B.L. Rob. & Greenm.) E.E. Schill. & Panero, Davilanthus E.E. Schill. & Panero, Dendroviguiera E.E. Schill. & Panero, Gonzalezia E.E. Schill. & Panero, Heliomeris Nutt., Hymenostephium Benth., Sidneya E.E. Schill. & Panero and Viguiera Kunth (Table 1).

The new classification of Viguiera reduces its number of species significantly, mainly restricted to South America. For North America (United States and Mexico), the genus includes two species (Viguiera dentata (Cav.) Spreng. and V. moreliana B.L. Turner (Turner 2015). Villaseñor (2016) reports for Viguiera nine species, but probably several of them are still not assigned to the genus to which they currently belong because they were not included in the molecular study that led to the reclassification of the Viguiera species. Future studies will certainly place them appropriately in the genus to which they belong.

Regarding the chemical studies of Viguiera, in 1985 the reports of the chemical compounds characterized from around 30 of the ca. 150 species included at that time in the genus (Romo de Vivar & Delgado 1985). Here we review the published secondary metabolites found in the 67 species were compiled reclassified in the nine genera segregated from Viguiera, according to the Schilling and Panero classification, and the biological activities for their extracts and secondary metabolites. The results allowed some chemotaxonomic observations and the analysis of the incidence of secondary metabolites between clades, which is discussed.

Materials and methods

The present study was accomplished by collecting the scientific data published on chemical compounds and biological activities of species of the genus Viguiera sensu lato between 1918 and 2021, using Scifinder, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar databases.

Results

Description of the chemical constituents. This section describes the main chemical constituents reported in the Viguiera species and species of the segregated genera. The studies have been carried out over the last decades, with varying methodologies and approaches. We detected chemical studies on 67 species (Appendixes 1-10) within the large Viguiera circumscription, and 322 secondary metabolites structurally characterized. Species of the genus Viguiera s.l. biosynthetize terpenoids represented mainly by sesquiterpene lactones (SLs) and diterpenes, although monoterpenes and triterpenes have also been found. Additionally, flavonoids, polyacetylenes, steroids, fatty acids and other hydroxylated and aromatic compounds are also reported.

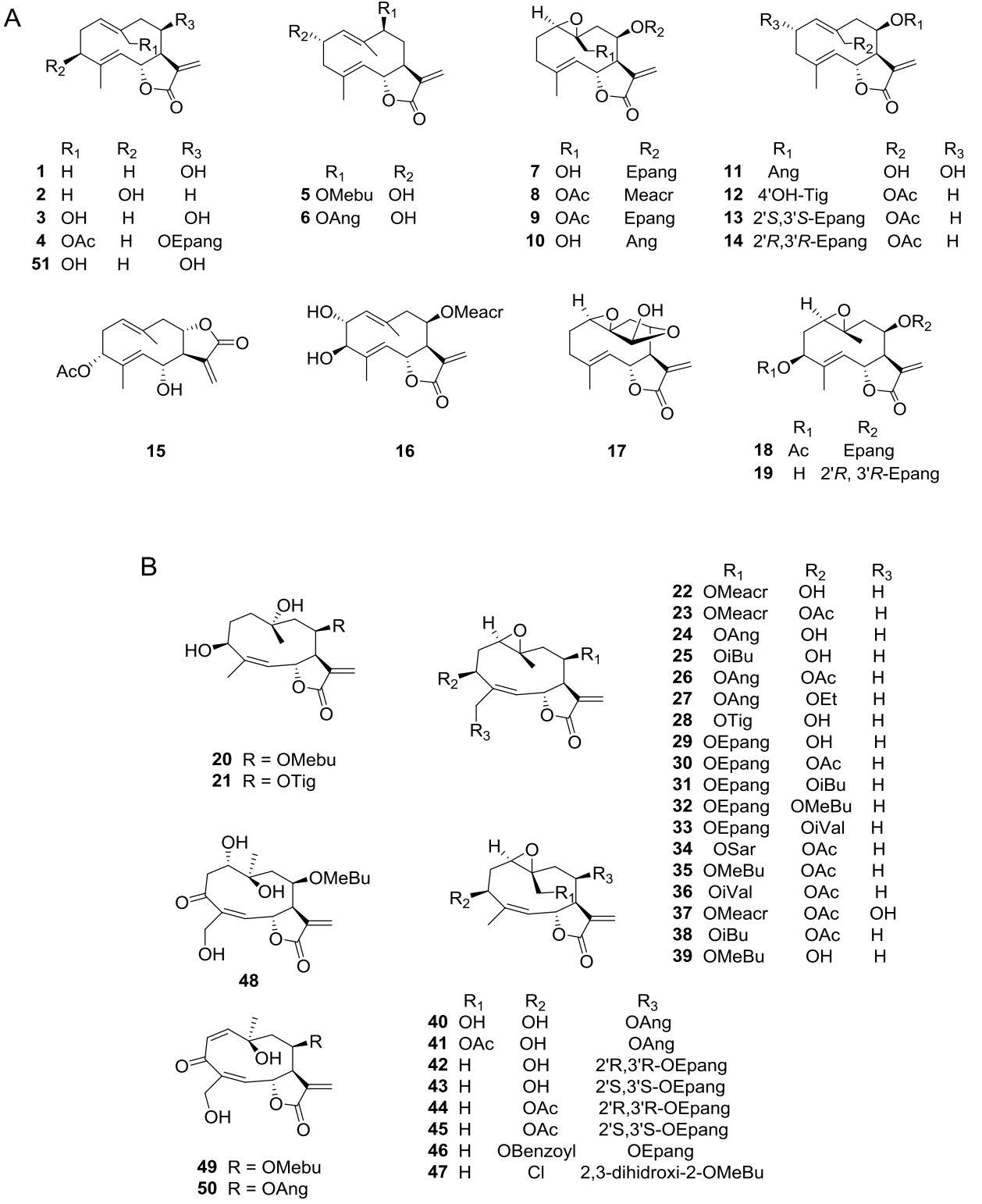

Sesquiterpene lactones (SLs) are major secondary metabolites in the Asteraceae family often used as chemotaxonomic markers (Da Costa et al. 2005); the Heliantheae tribe is rich in germacranolide-type compounds (Zdero & Bohlmann 1990). The characteristic SLs of the genus Viguiera s. l. have been reported in 35 of the 67 species studied and belong to the groups of germacrolides, heliangolides, furanoheliangolides, guaianolides, and eudesmanolides. Germacrolides (Figure 1A, 1-19, 51) have been reported in 12 species, heliangolides (Figure 1B, 20-50) have been isolated from 15 species, the most frequent compounds; furanoheliangolides (Figure 2A, 52-95); have been found in 27 species, guaianolides (Figure 2B, 96-107) in four species, and eudesmanolides (Figure 3A, 108-111) in five species. The presence of a 1,10-epoxy group is observed in germacrolides (7-10, 17-19) and in heliangolides (22-47). Most of them have an α-methylene 12,6-trans γ-lactone ring, except for 61 and 63, isolated from V. eriophora (=Aldama eriophora) and V. sylvatica (=Dendroviguiera sylvatica), respectively, with a saturated γ-lactone, and those isolated from V. deltoidea (=Bahiopsis deltoidea) (15), from V. pazensis and V. tucumanensis (=Aldama tucumanensis) (106 and 107), and from V. linearis (=Aldama linearis) and V. potosina (=Aldama canescens) (111), with a C-8 lactone closure.

Figure 1 A) Germacrolide-type sesquiterpene lactones from Viguiera s. l. species, B) Heliangolide-type sesquiterpene lactones from Viguiera s. l.

Figure 2 A) Furanoheliangolide-type sesquiterpene lactones from Viguiera s. l. species, B) Guaianolide-type sesquiterpene lactones from Viguiera s. l.

Figure 3 A) Eudesmanolide-type sesquiterpene lactones from Viguiera s. l. species, B) Acyclic diterpenoids in the genus Viguiera s. l., 3C: Bicyclic diterpenoids in the genus Viguiera s. l.

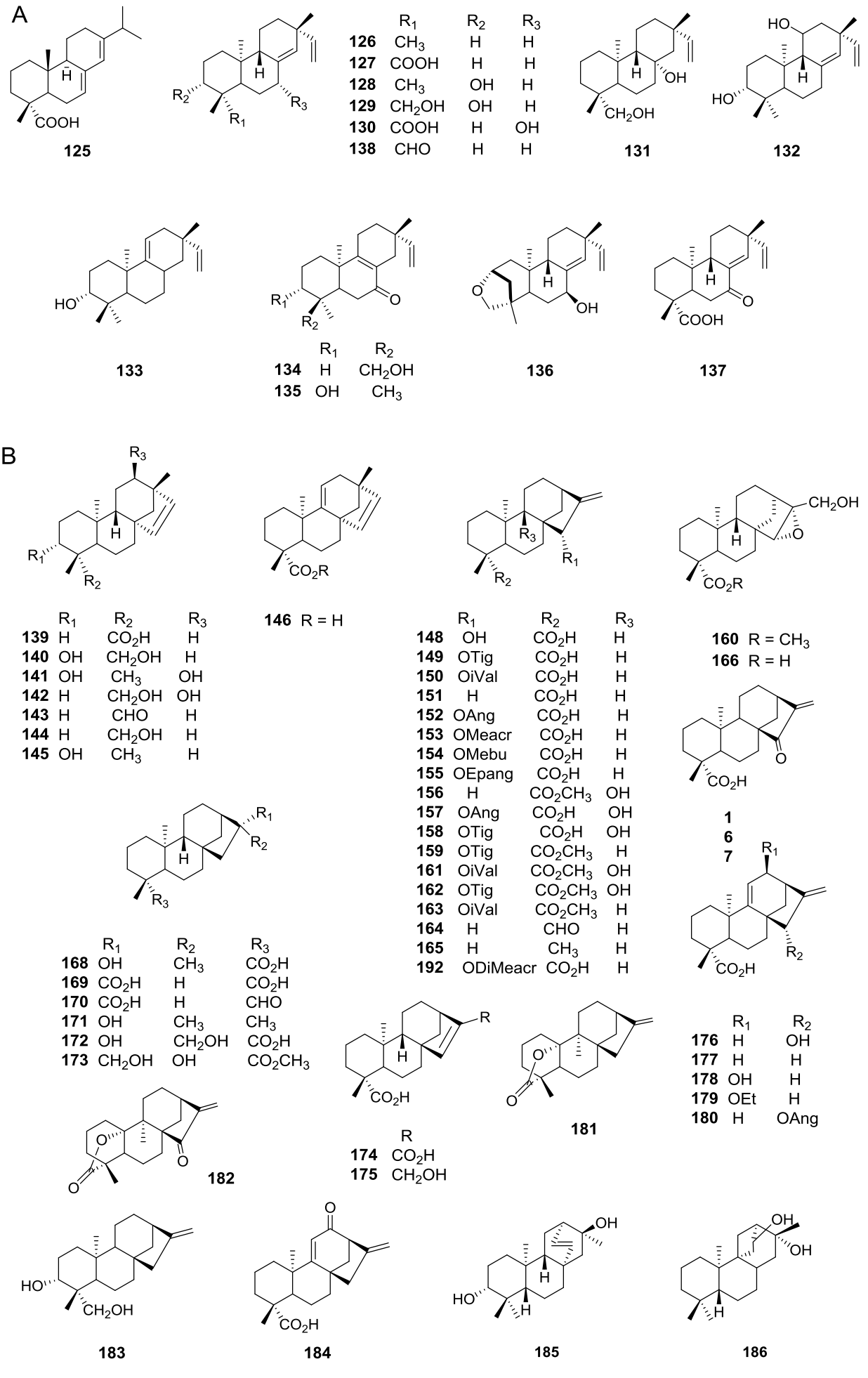

Diterpenes are also extensively distributed in the genus Viguiera s.l., present in 39 out of 67 species studied. Acyclic diterpenoids are represented by six phytanes (Figure 3B, 112-117) isolated from five species. Bicyclic diterpenoids have been isolated from seven species (Figure 3C, 118-124), the ent-labdanes 118 and 119 were isolated from V. robusta (=Aldama robusta) and V. stenoloba (=Sidneya tenuifolia), respectively, 120-122 were found in V. bishopii (=Aldama bishopii) and 121 in V. dentata, V. anchusifolia (=Aldama anchusifolia), V. pilosa (=Aldama pilosa), and V. robusta (=Aldama robusta), and the ent-clerodanes 123-124, were found in V. tucumanensis (=Aldama tucumanensis). Tricyclic diterpenoids have been isolated from seven species (Figure 4A): the abietane 125 was isolated from V. procumbens (A. helianthoides), the ent-pimaranes 126-132 and 137 from V. arenaria (=Aldama arenaria), 128 from V. robusta (=Aldama robusta), 133 from V. pinnatilobata (=Sidneya pinnatilobata), 134-136 from V. discolor (=Aldama discolor), and 138 from V. anchusifolia (=Aldama. anchusifolia) and V. nudibasilaris (=Aldama nudibasilaris). Tetracyclic diterpenes have been isolated from 32 species (Figure 4B), they are represented by ent-beyeranes (139-147), ent-kauranes (148-184, 192), an ent-atisane 185, and the villanovane 186. The pentacyclic diterpenes ent-trachylobanes 187-191 have been found in five species (Figure 5A).

Figure 4 A) Tricyclic diterpenoids in the genus Viguiera s. l. species, B) Tetracyclic diterpenoids in the genus Viguiera s. l.

Figure 5 A) Pentacyclic diterpenoids in the genus Viguiera s. l. species, B) Pentacyclic triterpenoids in the genus Viguiera s. l.

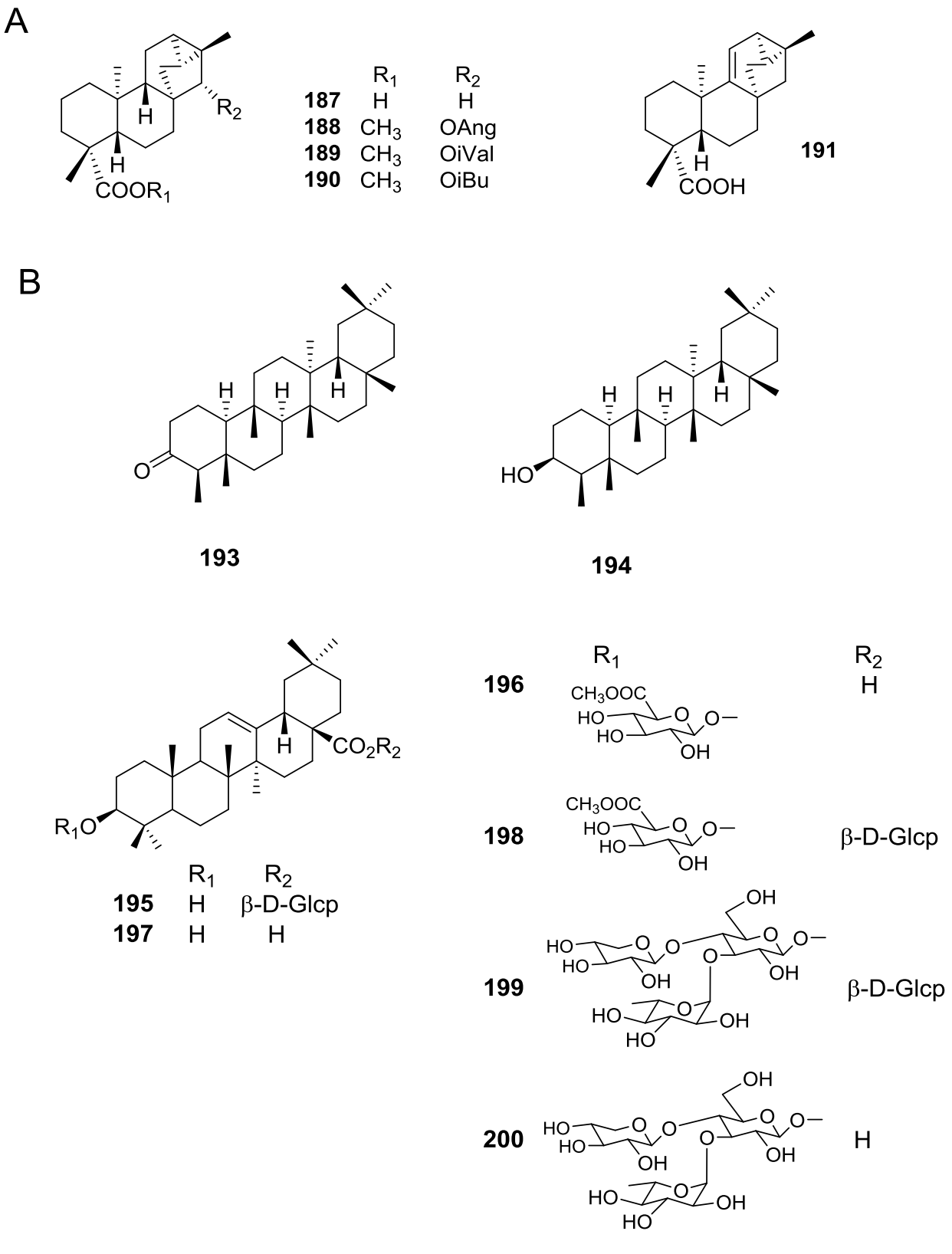

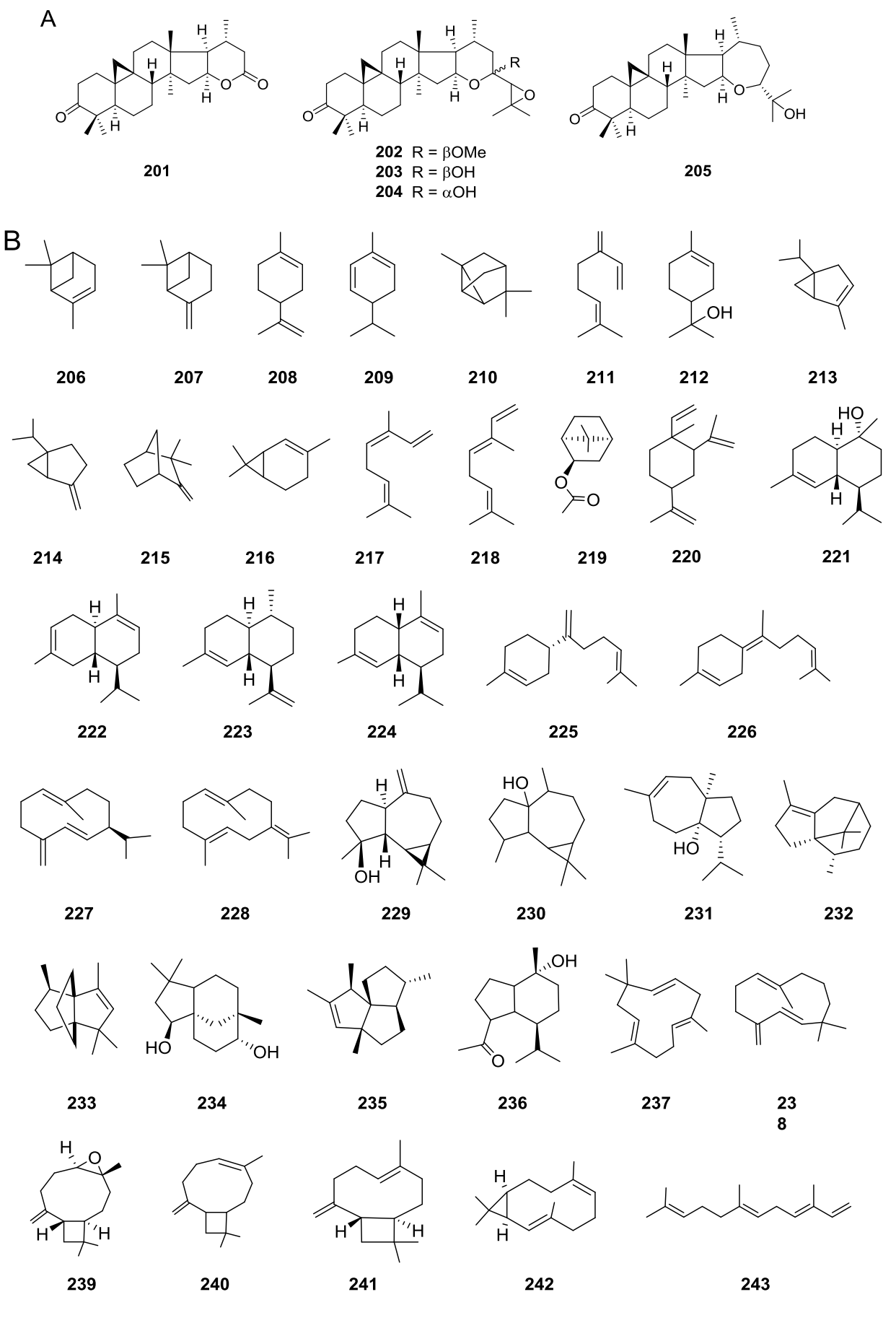

Pentacyclic triterpenoids (Figure 5B) have been isolated from V. decurrens (=Gonzalezia decurrens) (193-198) and V. hypargyrea (=Gonzalezia hypargyrea) (193-195, 197-200), while the cycloartane hexacyclic triterpenoids (Figure 6A) 201-204 have been found in V. dentata, and 205 in V. superaxillare (=Hymenostephium superaxillare) (Appendixes 5 and 8).

Figure 6 A) Hexacyclic triterpenoids in the genus Viguiera s. l. species, B) Volatile compounds obtained from Viguiera s. l. species.

Monoterpenoids (206-219) have been reported in essential oils. Non or low functionalized sesquiterpenoids (220-243) are also present in essential oils as well as in hexane extracts (Figure 6B).

Polyacetylenes (Figure 7A, 244-249) were also found in V. annua (=Heliomeris annua), V. procumbens (=Aldama helianthoides), V. incana (=Aldama incana), V. laceolata (=Aldama lanceolata), V. oblonguifolia (=Aldama oblongifolia), V. nervosa (=Aldama nervosa), V. pazensis, and V. stenoloba (=Sidneya tenuifolia) (Appendixes 1, 7, and 9).

Figure 7 A) Polyacetylenic compounds obtained from Viguiera s. l species. B) Flavonoids obtained from Viguiera s. l.

Several studies on flavonoids content have been published as part of the systematic analysis of the series of Viguiera species included in Blake’s (1918) revision of the genus. Initially, ultraviolet patterns were used to characterize the floral flavonoids involved in UV absorption among the species included in a taxonomic group (Reiseberg & Schilling 1985). In other studies, the flavonoid data were investigated to provide chemotaxonomic evidence on species relationships, both within the series and with other members of the genus (Schilling et al. 1988, Schilling & Panero 1988, Schilling 1989, Wollenweber et al. 1995). Flavonoids are represented by 46 structures isolated from 32 species (Figure 7B, Appendixes 1-5, 7, and 10), most of them are flavones (250-254, 258-266, 271-273, 279-284) found in 27 species. There are also reports of ten flavonols present in 12 species (267-270, 274-278, 285), five of them glycosylated, seven chalcones (286-292); two aurones (294, 295), three flavanones (255-257) isolated from V. laciniata (=Bahiopsis laciniata) and one flavanol (293) obtained from V. quinqueradiata (=Dendroviguiera quinqueradiata). Other phenolic compounds such as benzofuran (311) and benzopyran derivatives (296-299, 306, 307, 310, 312), caffeic acid and some of its esters (302-305), and stilbenes (308, 309) have been isolated (Figure 8A, Appendixes 1, 5, 7, and 10). Phytosterols (313-315), fatty acids (316-318), and phenyl alanine derivatives (320-321) have also been reported (Figure 8B).

Figure 8 A) Other phenolic compounds obtained from Viguiera s. l. species, B) Other compounds obtained from Viguiera s. l.

Description of extracts and pure compounds with biological activity. The biological activities of extracts or pure compounds from 18 species of Viguiera s.l. have been reported (Table 2).

Table 2: Biological activity of extracts and isolated compounds of the genus Viguiera s.l.

| Species | Activity | Extracts/Compounds | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| V. anchusifolia Baker (=Aldama anchusifolia (DC.) E.E. Schill. & Panero) | Trypanocidal | MeOH, CH2Cl2 | Selener et al. 2019 |

| V. annua (M.E. Jones) Blake (=Heliomeris annua (M.E. Jones) Cockerell) | Phototoxic | 244, 245 | Guillet et al. 1977 |

| V. arenaria Baker (=Aldama arenaria (Baker) E.E. Schill. & Panero | Muscle relaxant | 127 | Ambrosio et al. 2002, Tirapelli et al. 2004 |

| Antimicrobial | 127, 128, 131 | Porto et al. 2009a, 2009b | |

| 127, 151 | Soares et al. 2019a, b | ||

| 127, 128 | Carvalho et al. 2011, Marangoni et al. 2018, Ferreira et al. 2018 | ||

| Trypanocidal | 131, 127 | Ambrosio et al. 2008, Rocha et al. 2022 | |

| Anti-inflammatory | EtOH-H2O, MeOH-H2O | Chagas Paula et al. 2015 | |

| Anti-inflammatory and analgesic | 127 | Possebon et al. 2014, Mizokami et al. 2016 | |

| Antiproliferative activity | CHCl3, 127, 128 | De Oliveira et al. 2021 | |

| Genotoxic and anti- genotoxic effects | 127 | Kato et al. 2012 | |

| V. aspilioides Gardn. (=Aldama aspilioides (Baker) Schill. & Panero) | Trypanocidal | 151, 171, 187 | Da Costa et al. 1996a |

| Antibacetrial | 187 | Da Costa et al. 1998 | |

| V. bracteata Gardner (=Aldama bracteata (Gardner) E.E. Schill. & Panero) | Anti-inflammatory | EtOH-H2O, MeOH-H2O | Chagas Paula et al. 2015 |

| V. decurrens Gray (= Gonzalezia decurrens (A. Gray) E.E. Schill. & Panero) | Cytotoxic | Mixture of 195, 196, 315 | Marquina et al. 2001 |

| Insecticidal | 195, 198 | ||

| V. dentata (Cav.) Spreng. | Antimicrobial | 151, essential oil, hexane | Canales et al. 2008 |

| Antifungal | Hexane | ||

| V. discolor Baker (= Aldama discolor (Baker) E.E. Schill. & Panero) | Antiprotozoal | CH2Cl2, and 134, 183 | Nogueira et al. 2016 |

| Anti-inflammatory | EtOH-H2O, MeOH-H2O | Chagas-Paula et al. 2015 | |

| V. filifolia Sch. Bip. ex Baker (= Aldama filifolia (Sch.Bip. ex Baker) E.E. Schill. & Panero) | Anti-inflammatory | EtOH-H2O, MeOH-H2O | Chagas-Paula et al. 2015 |

| V. gardneri Baker (= Aldama gardneri (Baker) E.E. Schill. & Panero) | Anti-inflammatory | 101, 103, 104 | Schorr et al. 2002 |

| V. hypargyrea (Greenm.) Blake (= Gonzalezia hypargyrea (Greenm.) E.E. Schill. & Panero) | Cytotoxic | 17 | Arellano-Martinez & Delgado 2010 |

| Spasmolytic | Hexane, 139, 151 | Zamilpa et al. 2002 | |

| Antimicrobial | 139 | ||

| V. linearifolia Chodat. (= Aldama linearifolia (Chodat.) E.E. Schill. & Panero) | Anti-inflammatory | EtOH-H2O, MeOH-H2O | Chagas-Paula et al. 2015 |

| V. pinnatilobata (Sch. Bip.) var. megaphylla (= Sidneya pinnatilobata (Sch. Bip.) E.E. Schill. & Panero var. megaphylla (Butterw. ex B.L. Turner) E.E. Schill. & Panero) | Spasmolytic | 133 | Campos-Lozada et al. 1993 |

| V. robusta Gardn. (v= Aldama radula (Baker) E.E. Schill & Panero) | Analgesic anti-inflammatory | 52 151 | Arakawa et al. 2008 Valério et al. 2007, Nicolete et al. 2009. |

| Analgesic, anti-inflammatory, anti-arthritic | 151 | Fattori et al. 2018, Zarpalon et al. 2017 | |

| Inhibition of smooth muscle contractility | 127, 151 | Ambrosio et al. 2006 Tirapelli et al. 2002 | |

| Anti-inflammatory | EtOH-H2O, MeOH-H2O | Chagas-Paula et al. 2015 Vasconcelos Faleiro et al. 2021 | |

| V. sylvatica Klatt (= Dendroviguiera sylvatica (Klatt.) E.E. Schill. & Panero) | Anti-inflammatory | 52, 96 | Dupuy et al. 2008 |

| Cytotoxic | Taylor et al. 2008 | ||

| V. trichophylla Dusén (= Aldama trichophyla (Dusén) Magenta) | Anti-inflammatory | EtOH-H2O, MeOH-H2O | Chagas-Paula et al. 2015, Vasconcelos Faleiro et al. 2021 |

| V. tuberosa Griseb. (=Aldama tuberosa (Griseb.) E.E. Schill. & Panero) | Trypanocidal | MeOH, CH2Cl2 | Selener et al. 2019 |

| V. tucumanensis (Hook & Arn.) Griseb. (= Aldama tucumanensis (Hook. & Arn.) E.E. Schill. & Panero) | Phytotoxicity | 123 | Vaccarini et al. 1999 |

| Antifeedant | Vaccarini et al. 2001 | ||

| Cytotoxic | EtOH, 1, 24 | Gonzalez et al. 2018 |

Trypanocidal activity.- The CH2Cl2 extracts of the Argentinean species Aldama anchusifolia and A. tuberosa were more active than the MeOH extracts of the same plants against Trypanosoma cruzi; results showed 82 and 93 % of growth inhibition, respectively, with 100 µg/mL of CH2Cl2 extract (benznidazole was used as positive control) (Selener et al. 2019). A trypanocidal activity research of pimarane diterpenes isolated from Aldama arenaria described the activity of the ent-15-pimarene-8ß,19-diol (131) with IC50 of 116.5 ± 1.21 µM while that of the positive control, gentian violet, was 76 µM (Ambrosio et al. 2008). In other study ent-pimaradienoic acid (127) showed in-vitro trypanocidal activity with IC50 of 68.7 µM (reference compound: benznidazole, IC50 = 9.8 ± 0.68 µM), and the activity improved by esterification (Rocha et al. 2022). In vitro studies against T. cruzi identified the activity of compounds 151, 171, and 187 isolated from Aldama aspilioides (Da Costa et al. 1996a).

Insecticidal activity.- Phototoxic and insecticidal activities of polyacetylenes 244 and 245 isolated from V. annua (=Heliomeris annua (M.E. Jones) Cockerell) have been reported (Guillet et al. 1977). The insecticidal effect of saponins 195 and 198 isolated from Gonzalezia decurrens was evaluated on Epilachna varivestis larvae, these two saponines displayed activity with LC50 of 1380 and 80 mg/mol, respectively (Marquina et al. 2001). Clerodane 123 isolated from Aldama tucumanensis exhibited phytotoxicity against Sorghum halepense and Chenopodium album, and showed antifeedant activity (67 %) against Epilachna palentulata, (Vaccarini et al. 1999, 2001).

Anti-spasmolytic and relaxant activities.- The relaxant action on rat thoracic aorta of pimaradienoic acid (127), isolated from Aldama arenaria as well as its effect on the contraction of carotid rings were demonstrated (Ambrosio et al. 2002, Tirapelli et al. 2004). The effect on the inhibition of smooth muscle contractility by different concentrations of ent-kaurenoic acid (151) isolated from Aldama robusta was documented (Tirapelli et al. 2002). Diterpenes 127 and 151 inhibited vascular contractility mainly by blocking the extracellular Ca2+ influx (Ambrosio et al. 2006). The hexane extract of Gonzalezia hypargyrea showed spasmolytic activity, this activity was attributed to beyerenoic acid (139) by the inhibition of the electrically induced contractions of guinea pig ileum by 63.64 ± 6.1 %, with ED50 of 4.9 µg/ml (the positive control, papaverine showed inhibition of 82.8 ± 2.1 %) (Zamilpa et al. 2002). The spasmolytic effect of viguiepinol (133) obtained from V. pinnatilobata (=Sidneya pinnatilobata) was demonstrated in-vitro (Campos-Lozada et al. 1993).

Antimicrobial activity.- Dichloromethane extract of roots of Aldama arenaria and the isolated ent-pimarane derivatives 127, 128, and 131, displayed activity against gram-positive bacteria, showing the highest activities against Streptococcus agalantiae, S. dysgalantiae and Staphylococcus epidermis, with MIC values between 3.31 and 16.31 µM (vancomycin hydrochloride, used as positive control, showed MIC values between 0.34 and 0.47 µM); these compounds were also active against microorganisms responsible for dental caries with MIC values between 7.8 and 20.8 µM (chlorhexidine dihydrochloride, the positive control, showed MIC values between 0.16 and 0.64 µM) (Porto et al. 2009a, b). In other study, diterpene 127, isolated from V. arenaria was tested against clinically isolated gram-positive multi-resistant bacteria, and the results indicated that this compound was a promising antibacterial agent (Soares et al. 2019a, b). Compounds 127 and 128 showed activities against endodontic bacteria (Carvalho et al. 2011, Marangoni et al. 2018, Ferreira et al. 2018). The antibacterial activity of ent-traquilobanic acid (187), isolated from A. aspillioides, was tested against several gram positive bacteria showing the highest activity against S. aureus and S. epidermis (MIC 7.8 µg/ml, the positive control used in the screening phase was gentamicine) (Da Costa et al.1998). The antimicrobial activity of V. dentata’s essential oil, hexane extract, and 151, as well as the activity of the hexane extract was pointed out (Canales et al. 2008). Beyerenoic acid (139), isolated from Gonzalezia hypargyrea, inhibited the growth of Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus faecalis with a MIC of 12 µg/ml for each of them, using gentamicin as positive control (MIC 0.8 µg/mL) (Zamilpa et al. 2002).

Anti-inflammatory activity.- EtOH-H2O and MeOH-H2O extracts of Aldama arenaria, A. bracteata, A. discolor, A. filifolia, A. linearifolia, A. robusta, and A. trichophylla showed anti-inflammatory action through the inhibition of cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) and 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX) (Chagas-Paula et al. 2015). A study on leaf extracts of 22 Aldama species, using LC - MS metabolomics and in vitro enzymatic assays to indentify COX-1 and 5-LOX inhibitors, showed that A. robusta and A. trichophylla inhibited these two key enzymes (Vasconcelos Faleiro et al.). Pimaradienoic acid (127), from A. arenaria, showed anti-inflammatory effect in carrageenan-induced inflammation by reducing oxidative stress, nitric oxide, and cytokine production (Mizokami et al. 2016). The analgesic effects of diterpene 127 were demonstrated and associated with the inhibition of the NF-κB factor activation, reduction of cytokine production, and activation of the NO-cyclic GMP-protein kinase G-sensitive potassium signaling pathway (Possebon et al. 2014). Guaianolides 101, 103, 104, isolated from Aldama gardneri, showed anti-inflammatory activity inhibiting the transcription factor NF-κB (Schorr et al. 2002). Budlein A (52), isolated from Aldama robusta showed anti-inflammatory activity by the inhibition of inflammatory mediator release and neutrophil migration (Arakawa et al. 2008; Nicolete et al. 2009, Valério et al. 2007), inhibited the antigen-induced arthritis in mice and pain by targeting the NF-κB factor, does not induce in vivo side effects (Zarpelon et al. 2017), and reduced mechanical hypersensibility, knee joint edema pain and inflammation in a model of acute gout arthritis in mice (Fattori et al. 2018). SLs 52 and 96, isolated from Dendroviguiera sylvatica inhibited the nitric oxide production and phagocytosis of macrophages (Dupuy et al. 2008).

Genotoxic activity.- Pimaradienoic acid 127, isolated from A. arenaria, was studied for its in vitro and in vivo genotoxic and anti-genotoxic effects. In vitro results showed that 127 induces DNA damage at concentrations between 2.5 and 5.0 µg/mL, and in the in vivo evaluation of genotoxicity a significant damage was observed in the hepatocites of animals treated at 80 mg/Kg, compared with the control group (Kato et al. 2012).

Cytotoxic activity.- The CHCl3 extract of roots of A. arenaria and some fractions were evaluated in vitro for their antiproliferative activity against 10 tumor cell lines. The extract showed weak to moderate antiproliferative activities, while fractions enriched with diterpenes 127 and 128 presented moderate to potent activities in most of tested cell lines (de Olveira et al. 2021). The mixture of compounds 195, 196, and 315, isolated from Gonzalezia decurrens, showed cytotoxic activity against murine lukemia (ED50 2.3 µg/mL); however, the pure compounds were not active (Marquina et al. 2001). Hypargyrin A (17), a germacrolide from Gonzalezia hypargyrea showed mild activity against HeLa (cervical) and Hep-2 (larynx) cell lines, reported activities were IC50 35.1 ± 2.7 µM (positive control: 5-fluoro-uracil IC50 1.5 ± 0.19 µM) and IC50 39.2 ± 3.1 µM (positive control: 5-fluoro-uracil IC50 1.0 ± 0.17 µM), respectively; compound 17 displayed also a modest anti-inflammatory effect (Arellano-Martínez & Delgado 2010). The antiproliferative properties of SLs 52 and 96, isolated from V. sylvatica (=Dendroviguiera sylvatica), against cell lines in vitro and on the growth of melanoma tumors in mice were examined, results showed cytotoxicity in vitro and antitumor activity in vivo for SLs 52 (Taylor et al. 2008). Ethanol extract from V. tucumanensis (=Aldama tucumanensis) exhibited cytotoxic activity and two of its components, leptocarpin (24) and eupatolide (1), have shown significant cytotoxic properties (González et al. 2018).

Discussion

Comments on the biological activity of the secondary metabolites found in Viguiera s.l. The published biological activities of the secondary metabolites of Viguiera s.l. are but a tiny sample of the potential activities of those compounds; those activities reflect the interest of the researchers that assayed the metabolites. A common secondary metabolite trait is the ability to affect several physiological targets (Maffei et al. 2011, Hu & Bajorath 2013). Therefore, the biological activity of a secondary metabolite is usually multifunctional (Langenheim 1994; Gershenzon & Dudareva 2007), i.e., it can display activity on many wild species, pathogens or pathological processes in humans, as shown by Torres-Gurrola et al. (2016) with 364 secondary metabolites found in Persea americana.

On the relevance of phytochemical studies in Asteraceae. Phytochemical data are helpful to solve some taxonomic problems or for reinforcing certain phylogenetic relationships. Numerous publications highlight their taxonomic and ecological importance (for example, Seigler & Price 1976). In particular for the Asteraceae family, there are relevant publications on this topic, such as the results of symposia on the Biology and Chemistry of the Compositae (Heywood et al. 1977, Hind & Beentje, 1996), the contributions on its flavonoid content (Bohm & Stuessy 2001, Emerenciano et al. 2001), on its diterpenes and sesquiterpenes (Seaman 1982, Seaman et al. 1990, Spring & Buschmann 1996), and on its sesquiterpene lactones (Zidorn 2008, Shulha & Zidorn 2019). Especially noteworthy for Mexico are the summaries on the studies of secondary metabolites in the species of Viguiera and in species of the tribe Senecioneae (Romo de Vivar & Delgado et al. 1985, Romo de Vivar et al. 2007).

Figure 9 shows the placement of the species of Viguiera s.l. with chemical constituents’ reports following the phylogenetic relationships proposed by Schilling & Panero (2002, 2011). Nondistinctive patterns are observed between clades and chemical groups because all segregated genera share most main secondary metabolites (Appendixes 1-10), some of them more frequent than others in certain clades.

Figure 9 Cladogram illustrating the phylogenetic relationships between Viguiera species and segregated genera (Viguiera s. l.) with phytochemical studies discussed in this work (Adapted from Schilling & Panero (2002, 2011)).

The commonest secondary metabolites among the studied species are the flavonoids, followed by the tetracyclic diterpenoids and the furanoheliangolide-type sesquiterpene lactones. The chemical variants of each one has been recorded for the species (Appendixes 1-10), reaching a figure of 322 different secondary metabolites in just 67 species, an average of 5 per species.

There is a close relationship between certain clades indicated in Figure 9 with the classification proposed by Blake (1918). See Table S1. For example, most North American taxa included in his Subgenus Amphilepis now belong to different monophyletic genera. In this way, species of the genus Bahiopsis Kellogg are included in his Series Dentatae, the genus Calanticaria (B.L. Rob. & Greenm.) E.E. Schill. & Panero in his Series Brevifolia, the genus Gonzalezia E.E. Schill. & Panero corresponds to his Section Hypargyrea (Subgenus Amphilepis), or the genus Sidneya E.E. Schill. & Panero to his Series Pinnatilobatae. Table S1 includes the species with phytochemical studies arranged following the Blake´s classification.

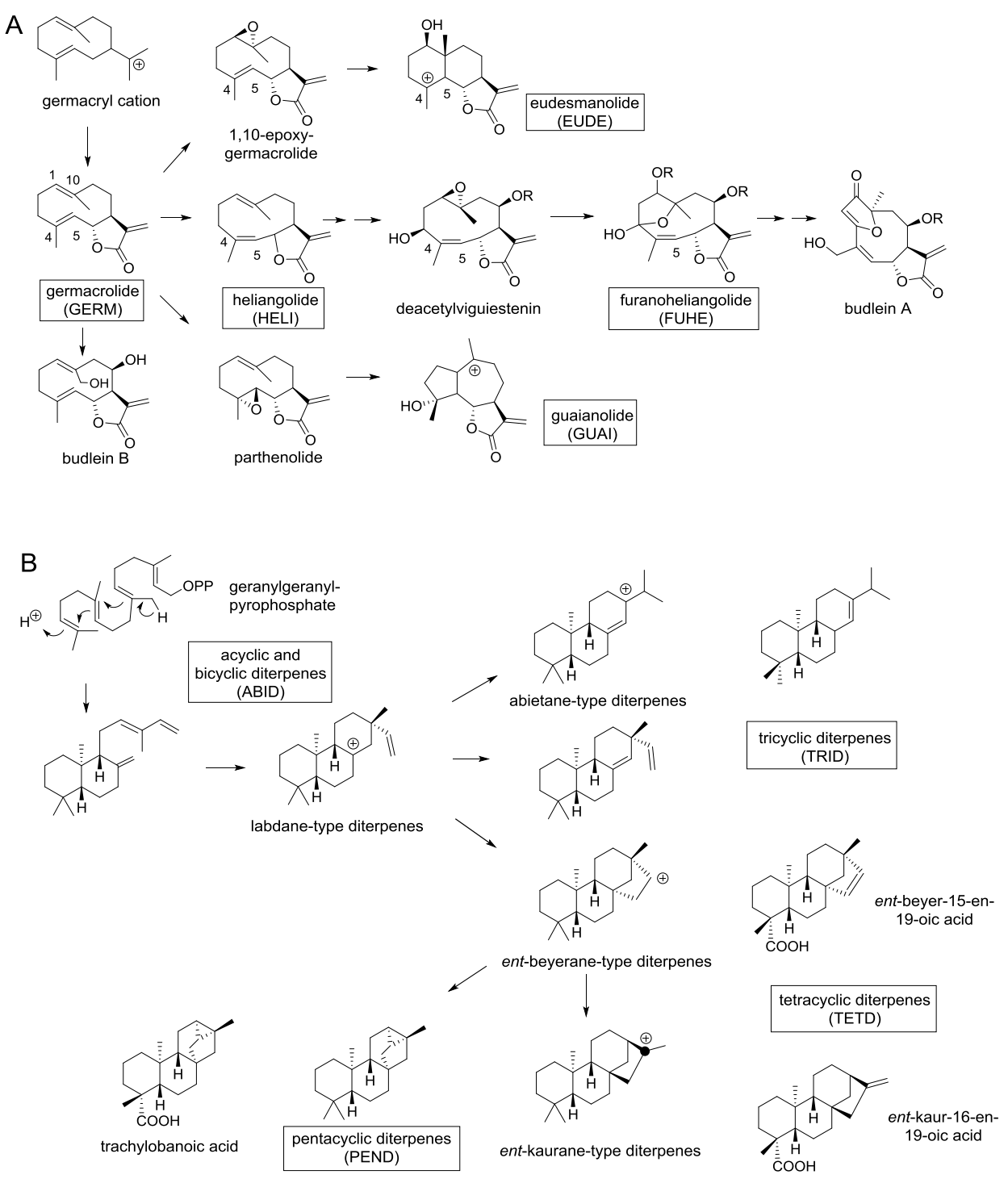

Chemotaxonomic observations. The secondary metabolites present in Viguiera s.l. species are terpenoids, polyacetylenes, flavonoids, phenols, and others. As previously noted, sesquiterpene lactones, polycyclic, diterpenes and flavonoids are the major groups of secondary metabolites in Viguiera s.l. species. Therefore, to compare the metabolic content among the segregated genera, the SLs and polycyclic diterpenes were divided according their biogenetic complexity and / or structural type, as shown in Figures 10A and 10B. Sesquiterpene lactones are biosynthesized from germacryl cation to germacrolides (i.e., budlein B), which is closely related to heliangolides (i.e., deacetylviguiestenin) and the formation of the C3-C10 epoxide affords the furanoheliangolides (i.e., budlein A). Cyclization of germacrolides produces eudesmanolides, while the 4,5-epoxy-germacrolides (i.e., parthenolide) are the precursors of guaianolides. Thus, sesquiterpene lactones were divided in five groups: germacrolides (GERM), heliangolides (HELI), furanoheliangolides (FUHE), guaianolides (GUAI) and eudesmanolides (EUDE). See Figure 10A.

Figure 10 A) Biogenetic relationships of the major type of sesquiterpene lactones found in Viguiera s. l. species and their acronyms, B) Biogenetic relationships of the major type of diterpenes found in Viguiera s. l. species and their acronyms.

Geranyl pyrophosphate is considered the direct precursor of linear (acyclic) diterpenes, and cyclization of this compound affords the bicyclic copalyl-pyrofosfate, which in turn produces tricyclic compounds (i.e., abietane and labdane diterpenes). Cyclization of the labdane diterpenes affords tetracyclic ent-beyerane and ent-kaurane diterpenes. Additional cyclization of tetracyclic diterpenes produces pentacyclic diterpenes (i.e. trachylobanoic acid). Diterpenes were divided in acyclic and bicyclic diterpenes (ABID), tri- (TRID), tetra- (TETD) and pentacyclic diterpenes (PEND). See Figure 10B.

Table 3 provides an overview about the occurrence of different types of secondary metabolites reported per each species (distributed in Viguiera and its segregated genera).

Table 3 Distribution of the occurrence of secondary metabolites in the new genera / species segregated from Viguiera. Germacrolides (GERM), heliangolides (HELI), furanoheliangolides (FUHE), guaianolides (GUAI), eudesmanolides (EUDE), acyclic plus bicyclic diterpenes (ABID), tri- (TRID), tetra- (TETD), penta- cyclic (PEND) diterpenes, pentacyclic triterpenes (PENT), and flavonoids (FLAV).

| Species | GERM | HELI | FUHE | GUAI | EUDE | ABID | TRID | TETD | PEND | PENT | FLAV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Aldama anchusifolia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 Aldama angustifolia | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 Aldama arenaria | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 Aldama aspilioides | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 Aldama bishopii | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 Aldama bracteata | 2 | 3 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 Aldama buddleiajiformis | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 8 Aldama canescens | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 Aldama cordifolia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 Aldama discolor | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 Aldama excelsa | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 Aldama filifolia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 13 Aldama gadneri | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 14 Aldama gilliesii | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 15 Aldama ghiesbreghtii | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 16 Aldama helienthoides | 2 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 17 Aldama hypochlora | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 18 Aldama incana | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 19 Aldama lanceolata | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 20 Aldama latibracteata | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 21 Aldama linearifolia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 22 Aldama linearis | 2 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 23 Aldama mollis | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 24 Aldama nervosa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 25 Aldama nudibasilaris | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 26 Aldama oblongifolia | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 27 Aldama pilosa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 28 Aldama robusta | 7 | 4 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 29 Aldama squarrosa | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 30 Aldama trichophyla | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 31 Aldama tucumanensis | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 32 Bahiopsis chenopodina | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| 33 Bahiopsis deltoidea | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| 34 Bahiopsis laciniata | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| 35 Bahiopsis lanata | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 36 Bahiopsis microphylla | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 37 Bahiopsis parishii | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 38 Bahiopsis reticulata | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 39 Bahiopsis subincisa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 40 Bahiopsis tomentosa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 41 Bahiopsis triangularis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| 42 Calanticaria bicolor | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 43 Calanticaria brevifolia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| 44 Calanticaria graggi | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 15 |

| 45 Dendroviguiera adenophylla | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| 46 Dendroviguiera eriophora | 0 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 14 |

| 47 Dendroviguiera insisgnis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 48 Dendroviguiera neocronquistii | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 49 Dendroviguiera oaxacana | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 50 Dendroviguiera pringlei | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| 51 Dendroviguiera puruana | 1 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 52 Dendroviguiera quinqueradiata | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| 53 Dendroviguiera sphaerocephala | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 |

| 54 Dendroviguiera splendens | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| 55 Dendroviguiera sylvatica | 0 | 1 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 56 Gonzalezia decurrens | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 2 |

| 57 Gonzalezia hypargyrea | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 7 | 3 |

| 58 Gonzalezia rosei | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 59 Helianthus porteri | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 60 Heliomeris annua | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 61 Heliomeris multiflora | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 62 Hymenostephium cordatum | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 63 Hymenostephium superaxillare | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 64 Sidneya pinnatilobata | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 65 Sidneya tenuifolia | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 66 Viguiera dentata | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 9 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| 67 Viguira pazensis | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 4 | 0 | 2 |

Observations on the incidence of the secondary metabolites of Viguiera s.l. species. According to the data shown in Appendixes 1-10 and Table 3, twenty five out of 31 Aldama species with chemical studies deal on the constituents of the aerial parts, and these report sesquiterpene lactones and tetracyclic triterpenes (entries 2, 3, 5-8, 10,11, 13-24, 26, 28, 29, 30, 31 of Table 3) as the main constituents. The 95 SLs reported for 20 Aldama species include 50 furanoheliangolides, 19 heliangolides, 16 germacrolides, seven guaianolides and three eudesmanolides. The roots and / or the essential oils were chemically investigated for 16 Aldama species (entries 1, 3-5, 9, 12, 16, 18, 19, 21, 22, 24, 25, 27, 28, 30 of Table 3). For Aldama species, it is evident that furanoheliangolides (FUHE) and tetracyclic diterpenes (TETD) are the prevalent chemical groups in the leaves.

Chemical analysis of the leaves of three species of Bahiopsis (entries 33, 34, 36 of Table 3) afforded sesquiterpene lactones of several types (GERM, HELI, FUHE, GUAI, EUDE). Almost all species of this genus contain flavonoids (FLAV).

Furanoheliangolides (FUHE) and tetracyclic diterpenes (TETD) have been informed as constituents of the aerial parts of Calanticaria greggi, in addition to the flavonoids (FLAV) in the three species (entries 42-44).

The flavonoid chemistry of Dendroviguiera species (entries 45-55) was discussed previously, considering that this group was part of the Section Maculatae of the Viguiera genus s.l. (Schilling & Panero 1988). Germacrolides (GERM), heliangolides (HELI) and furanoheliangolides (FUHE) and tetracyclic diterpenes (TETD) have been characterized from Dendroviguiera species. A high infraspecific diversity in the chemical constituents has been noted in this group (considering the less abundant presence of 1-keto-2,3-unsaturated furanoheliangolides), and it has been suggested that the lack of SLs in some species (entries 47 and 49 of Table 3) may be related to the absence of glandular trichomes (Spring et al. 2000).

In addition to flavonoids (FLAV), tetracyclic ditepenes (TETD) and pentacyclic triterpenes (PENT) have been characterized in Gonzalezia. The members of Gonzalezia were recognized as a monophyletic group (Wollenweber et al. 1995). It is noteworthy that exclusively germacrolides (GERM) have been characterized from the aerial parts of G. hypargyrea (Álvarez et al. 1985, Arellano & Delgado 2010).

Heliangolides (HELI), furanoheliangolides (FUHE) and bi- and tetracyclic diterpenes are the main constituents of Sidneya.

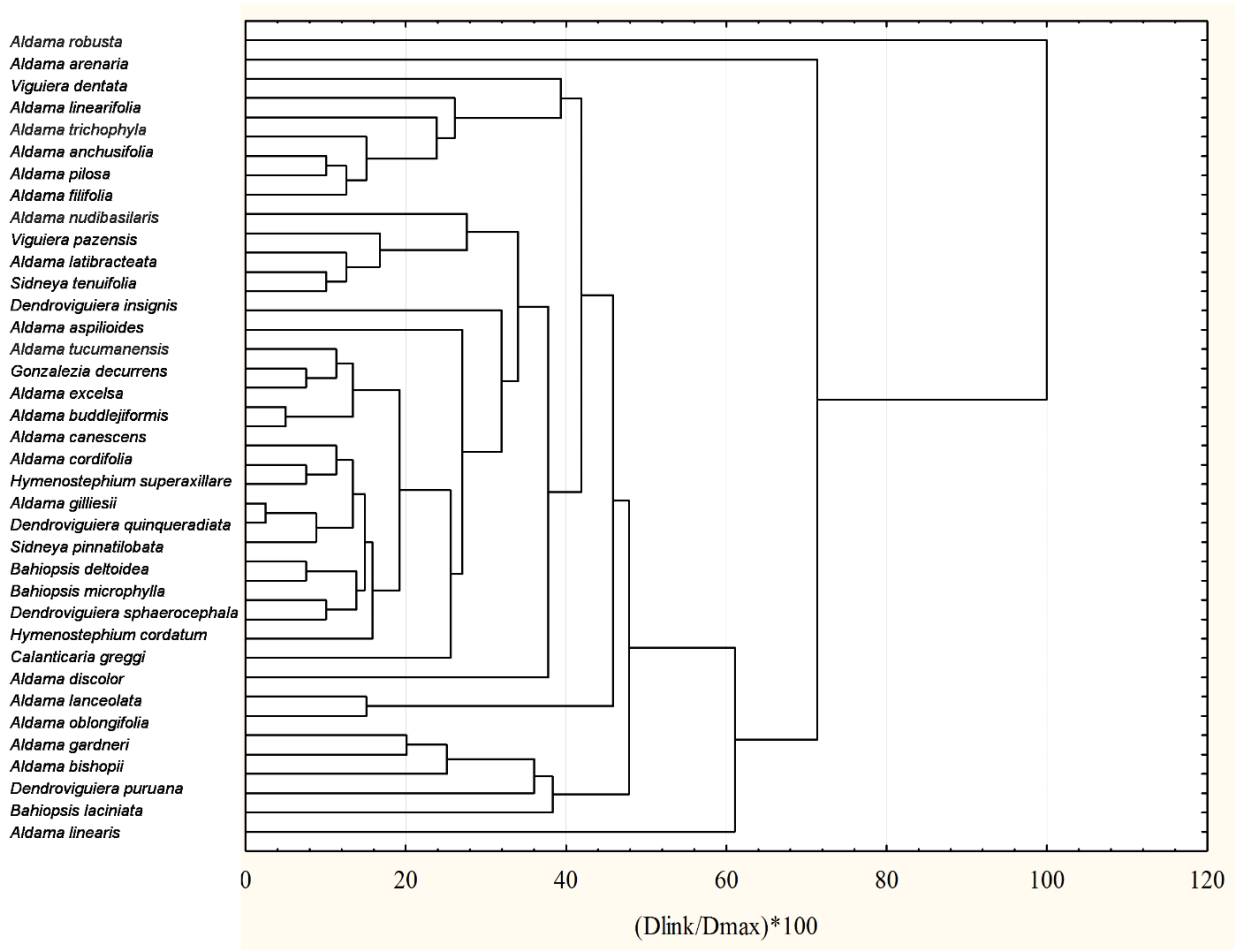

To explore if the species segregated from Viguiera grouped according to the secondary metabolites found in those species, we performed a cluster analysis with four types of sesquiterpene lactones and bi-, tri-, and tetra-terpenoids and the 38 species remaining after eliminating those that had no sesquiterpene lactones and those terpenoids (Figure 11).

Figure 11 Classification of 38 species formerly classified in the genus Viguiera according to their content of four types of sesquiterpene lactones, and bi-, tri-, and tetra-terpenoids. The distance matrix was built with city-block (Manhattan) distances and the grouping algorithm was the unweighted pair-group average.

The species grouping does not coincide with the phylogenetic clusters shown in Figure 9. In many cases, species classified closely belong to different genera, and the species in the same genus were classified away from their congeneric species. We do not have the certainty that all the secondary metabolites analyzed in Figure 11 used were searched and detected in all species. However, the absence of correlation between the phylogenetic and phytochemical classifications is consistent with a similar comparison made with Jacobaea species and their pyrrolizidine alkaloids, where the authors concluded that the distribution of the alkaloids was determined by ecological factors (Chen et al. 2022). Thus, we suggest that the sesquiterpene lactones and diterpenes characterized until now are not sufficiently informative as chemotaxonomic markers to make clear distinctions between the segregated genera from Viguiera.

Theoretical or methodological assumptions can explain the lack of distinctive chemotaxonomic patterns among Viguiera s.l. One is the lack of certainty that all species have been studied in the same way; for example, the studies of Schilling et al. (1988) or Schilling & Panero (1988) focused on the study of flavonoids, considerably increasing the number of species studied in this particular type of compounds, many of them poorly or never studied in search of other compounds. Other studies focused mainly on SLs, avoiding the search other compounds. Furthermore, intraspecific phytochemical variation is a generalized phenomenon found diurnal, seasonal variations, by attack of herbivores or pathogens, and by ontogeny of tissues or individuals. In addition, there is also variation within and between individuals and populations (García-Rodríguez et al. 2012, Espinosa-García et al. 2021). Furthermore, perhaps for several Viguiera s.l. species the biosynthetic route for several metabolites has been lost or blocked against other more ecologically fruitful compounds; however, the test to probe the latter rarely is assessed.

In conclusion, the review of the natural products structurally characterized from Viguiera species and newly segregated genera allowed the recognition of 322 different substances in 67 species of 10 genera. The chemical constituents most frequently found are sesquiterpene lactones, diterpenes and flavonoids, and the published biological activities of extracts and pure compounds were compiled. The detailed analysis us to identify that germacrolides, heliangolides, furanoheliangolides, and ent-kaurene-type diterpenes are the constituents that best characterize this group of plants. Some comparisons between genera allowed to establish that furanoheliangolides are the type of sesquiterpene lactones that best characterize the genus Aldama. However, no direct relationships were identified between different genera and their chemical constituents.

The data obtained from the study of secondary metabolites will continue to be an essential source in collecting of comparative data for plant systematics. Some studies discussing phylogenetic relationships have shown congruence in the data obtained from the study of micro (secondary metabolites) and macromolecules (DNA sequences) (e.g., Grayer et al. 1999). We recommend the analysis of a broader spectrum of species to reach more robust chemotaxonomic conclusions. The lack of substantial taxonomic information obtained among the secondary metabolites and species may be due to the low number of species studied to date. Therefore, complementary, large-scale phytochemistry (plant metabolomics) combined with bioinformatics undoubtedly will provide massive metabolite profiles that will have a major impact in many areas of scientific research, such as systematics (Sumner et al. 2003).

Supplementary material

Table S1. Species of Viguiera s. l. arranged according to the S. F. Blake’s (1918) classification can be accessed here: https://doi.org/10.17129/botsci.3072

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)