Flowers are the reproductive structures of angiosperms, which appeared in the plant kingdom 130 to 250 million years ago (Soltis et al. 2011, Doyle 2012, Hochuli & Feist-Burkhardt 2013, Magallón et al. 2013, Sauquet et al. 2017). Flowers consist of a perianth, which is the striking part of the flower made up of the petals and tepals, the androecium (masculine reproductive parts), and they gynoecium (feminine reproductive parts) (Zomlefer 1994).

Due to their aesthetic, organoleptic, innocuous, nutritional, and medicinal characteristics, flowers have been incorporated into the diet of multiple cultures as a food resource (Lu et al. 2016, Zheng et al. 2018). Edible flowers’ relevance in the diet is due to their bioactive compounds, which have effects on the human body and modify its function. Many of these compounds are secondary metabolites that are produced by plants as a defense mechanism against herbivores; these compounds include alkaloids, terpenes, flavonoids, glycoside, saponins, among others (Barros et al. 2010, Wongwattanasathien et al. 2010, Kaisoon et al. 2011, Lu et al. 2016, Zheng et al. 2018). Flowers also contain high contents of pigments such as carotenoids and anthocyanins, which are responsible for their colors and have the function of attracting pollinators. These anthocyanins, polyphenols, flavonoids, and carotenoids have been associated with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities and prevention of chronic degenerative diseases (Kaisoon et al. 2011, 2012, Benvenuti et al. 2016, Pires et al. 2018).

Given the presence of these bioactive compounds, the consumption of flowers has generated interest in the field of health. Their nutritional and functional characteristics provide physiological benefits, which contribute to improving health and may reduce the risk of certain diseases (Loizzo et al. 2016). It is therefore important to conduct studies on the bioactive substances present in these resources, since they allow us to determine their quality and nutraceutical and medicinal potential (Mlcek & Rop 2011, Zheng et al. 2018).

In Mexico, of the 26,000-30,000 higher plants that have been described, about 2,168 are edible (Villaseñor 2016, Ulloa et al. 2017). Flowers are consumed from 67 of these species, which belong to 49 genera from 25 families, mainly the families Asparagaceae (23 species of the subfamily Agavoideae), Fabaceae (23 species), Cactaceae (12 species), Arecaceae (5 species) and Cucurbitaceae (4 species) (Mapes & Basurto 2016).

The use of flowers as food in Mexico dates back to pre-Hispanic times and was documented in the texts of chroniclers and evangelizers. Examples include flowers that were eaten directly, such as huauhquílitl (Chenopodium berlandieri subsp. nuttalliae (Saff.) H.D. Wilson & Heiser), pumpkin and zucchini flowers, called ayoxochquílitl (Cucurbita spp.), as well as flowers used to give aromas and flavors to beverages, such as quauhxiúhtic, itzcuinyoloxóchitl and eloxochiquáhuitl (Sahagún 1999). Flowers are still consumed in Mexico, especially in rural and indigenous communities, where the practices for their harvest, production, use, and preparation were developed and have been maintained (Ordoñez & Pardo 1982, Rangel 1987, LaFerriere et al. 1991, Mares 2003, Centurión et al. 2004, Chávez 2010). In Mexico, edible flowers are considered to belong to the category of quelites (from Nahuatl quilitl = edible herb), a generic term used to refer to edible stems, leaves and flowers, which includes seasonal food collected from the wild or associated to other main crops such as maize (Bye 1981, Mapes & Basurto 2016).

In the arid zones of Mexico, most of the flowers consumed are from cacti and agaves, while in tropical climates, they are mainly palm flowers (Arecaceae) (Mapes & Basurto 2016). Most of these are native and wild, and therefore are extracted from natural ecosystems. These genetic resources represent an important usable biological material, since in addition to the great genetic diversity contained, they play a crucial role in the daily life of many people. They are self-consumption resources, form part of the daily diet, are elements of the identity of cultural groups, and generate income for families when they are sold (Casas & Parra 2017).

Generally, these resources are commercialized locally by small producers or gatherers, mostly women, in local and traditional markets. Local and traditional markets are spaces where products native to the regions where they are established are commercialized and exchanged, and they are a source of knowledge of the biological and cultural diversity of rural and indigenous communities (Bye & Linares 1983).

In recent decades, the consumption of flowers has presented a strong dichotomy. On the one hand, because they are a seasonally gathered food and historically consumed by rural or indigenous populations, they have been assigned negative stigmas and prejudices, disparaging their consumption. This has led to the decrease in commercialization and consumption of many of these products (even in the localities where they are produced), which is accompanied by a loss of traditional knowledge including the methods for obtaining flowers (e.g., timing of collection, the forms of harvesting, and propagation), as well as the methods and recipes for consuming them. At the same time, there has been growing interest in this food group, which has led to gourmet restaurants featuring flower dishes and an increase in the publication of recipe books with these recipes. The gastronomy of "floriphagia" has become popular for offering visually attractive and fresh dishes with exotic aromas and delicate flavors (Pires et al. 2018, Fernandes et al. 2019).

Under this scenario, edible flowers are simultaneously being abandoned by the cultures that have developed the body of knowledge necessary for their production, and subject to a growing demand from cities due to their great nutritional potential. The combination of these two phenomena could lead to overexploitation of these resources. Without adequate management strategies to ensure their maintenance, this could lead to the decline of the populations of these resources and a deterioration of the ecosystems to which they belong (López 2008).

The objectives of this research were 1) to document the edible flowers that are commercialized in local markets of the city of Pachuca de Soto, Hidalgo (central Mexico), 2) to describe their forms of preparation, 3) to synthesize their nutritional contributions to the diet and conservation category and criteria through a bibliographic review. We analyze the state of management and conservation of these genetic resources and aimed to contribute to the revaluation of these foods and the people who produce them.

Materials and methods

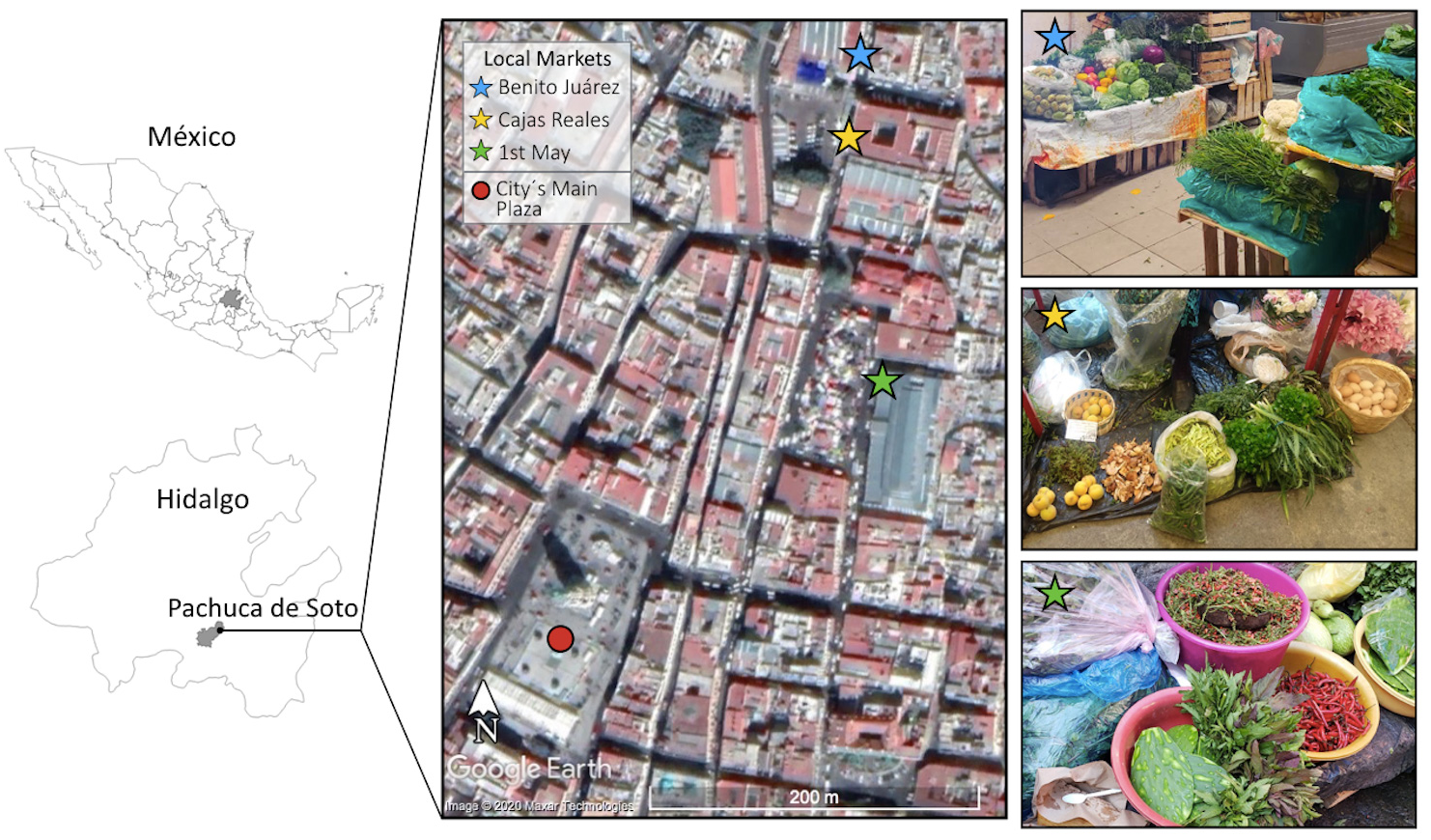

Study site. For this research, three flower marketing points were visited-the Mercado 1ro. de Mayo, Mercado Benito Juárez, and a street vendor in the Cajas Reales area. These spaces have been in operation for over 70 years in the city of Pachuca de Soto. The sales spaces studied were movable street stalls that are concentrated on weekends, located around the perimeter of the market buildings (Figure 1).

The number of stalls selling edible flowers varied over time; of the 11 stalls identified, we considered only the six stalls that were constant. Four were in Cajas Reales, one was in the Mercado Benito Juárez, and one in the Mercado 1ro de Mayo.

Market visits and information gathering. At the beginning of the research, we established contact with the vendors, presented the study project, its aims and methods and asked their consent to collaborate with us. The written testimonies and photographs were taken only after receiving verbal permission. This research was carried out following the Latin American Society of Ethnobiology’s (SOLAE) the Code of Ethics for research, action research, and ethno-scientific collaboration in Latin America. From January 2019 to January 2020, two visits were made per month. The purchase interview technique was carried out (Bye & Linares 1983), and semi-structured interviews (n = 40, Bernard 1995) were conducted in order to investigate biocultural data on the edible flowers, organized into the following questions: 1) the common names by which the flower is known, 2) how to prepare it, 3) source of the resource, i.e., if the flower was cultivated or collected from the wild, and 4) locality where the flower originated. In addition, direct observations were made, and we photographed the edible flowers that were for sale. We used the online platform Naturalista (www.naturalista.mx), the book “Plantas útiles del estado de Hidalgo” (Villavicencio & Pérez 2006), and the dichotomous keys in Flora Fanerogámica del Valle de México (Rzedowski & Rzedowski 2005), to identify the flowers to the species level.

Nutritional content and conservation status. The nutritional information of the flowers was compiled by reviewing the literature. The Ethnobotanical Plant Database of Mexico (Base de Datos Etnobotánicos de Plantas de México, (Caballero et al. 2020 BADEPLAM) was consulted to compare with the records obtained in this study. BADEPLAM is a database of the current state of knowledge of plant-human interaction, was created by Dr. Javier Caballero, renowned ethnobiologist at the Botanical Garden of UNAM, Mexico, where information has been compiled for some 30 years (Clement et al. 2021).

NOM-059 (SEMARNAT 2010), the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN 2020) and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) were consulted to determine the conservation status of the wild species.

Results

Markets and vendors. The largest number of vendors were present during weekend days, although some sold their products every three days depending on the availability and quantity of flowers they managed to obtain. The information from the six main vendors studied is shown in Table 1. The vendors had been attending these local markets to sell their products for decades, and they belonged to different ethnic groups from neighboring rural communities (Table 1). The main town of origin of the vendors, as well as the locality where they obtained their products, was San Miguel Cerezo in the Pachuca de Soto municipality.

Table 1 Characteristics of the vendors studied in the markets of Pachuca de Soto, Hidalgo.

| Vendor | Local market | Locality of origin | Gender | Age | Cultural group | Edible flowers for sale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Benito Juárez | Santiago de Anaya, Hgo. | Female | 80 | Hñähñu | Gualumbo, flor de sotol, flor de palma, garambullo, huauzontles, flor de calabacita, flor de madroño |

| 2 | Cajas Reales | Acaxochitlán, Hgo. | Female | 50 | Nahua | Flor de ayocote, pemuches |

| 3 | Cajas Reales | San Miguel Cerezo, Hgo. | Female | 50 | Mestizo | Gualumbo, flor de sotol, flor de palma, flor de sábila, garambullo, flor de calabacita, flor de madroño |

| 4 | Cajas Reales | San Miguel Cerezo, Hgo. | Female | 55-60 | Mestizo | Gualumbo, flor de sotol, flor de palma, garambullos, flor de calabacitas, flor de madroño, flor de cuaresma |

| 5 | Cajas Reales | San Miguel Cerezo, Hgo. | Male | 27 | Mestizo | Gualumbo, flor de palma, garambullo, huauzontles, flor de calabacita, flor de madroño |

| 6 | 1ro. de Mayo | San Miguel Cerezo, Hgo. | Female | 80 | Hñähñu | Gualumbo, flor de sotol, flor de palma, huauzontles, flor de calabacita, flor de calabaza grande. |

The unit of sale of small flowers was the lata (tin) these are 425-gram net weight. They were also sold in plastic bags containing one or two latas. Larger flowers were sold by manojo (bundle, 100 to 300 g). Flower prices ranged from 10-15 Mexican pesos (0.5-0.75 USD) per unit (manojo or lata). When the flower season was over and their abundance therefore decreased, the unit price increased to 20-25 Mexican pesos (1 USD). The vendors collected the flowers from xerophilous scrub, which they refer to as the cerro (the hill) and from pine-oak forests, which they call the monte (the mountains) or cultivate them in their milpa or homegardens.

Edible flowers. Twelve types of edible flowers were recorded, corresponding to 13 taxonomic entities (Table 2). The plant family with the largest number of edible flowers recorded in the markets was Asparagaceae, with four species. The most frequently sold flower was the Gualumbo (Agave salmiana Otto ex Salm-Dyck and A. mapisaga Trel.); it was marketed in five of the six stalls at quantities of more than 15 kilogram (kg) per week. The flower that was available for the largest portion of the year (seven months) was the Huauzontle (Chenopodium berlandieri subsp. nuttalliae). The characteristics of each recorded flower and its associated nutrients and bioactive compounds are described below:

Table 2 Edible flowers recorded in the local markets studied of Pachuca de Soto, Hidalgo.

| Common name | Family | Species | Origin | Managemet | Cooking method | Temporality | Consumption in other states | NOM-059 | IUCN | CITES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huauzontle | Amaranthaceae | Chenopodium berlandieri subsp. nuttalliae | N | Cultivated | 4, 5, 7 | March to September | Baja California, Guerrero, Oaxaca | NO | NE | NE |

| Gualumbo | Asparagaceae | Agave salmiana | N | Wild harvest (xeric shrublands) and cultivated | 1, 2, 3, 4, 6,8 | March to May | Puebla | NO | LC | NE |

| Asparagaceae | A. mapisaga | N | Cultivated | 1, 2, 3, 4, 6,8 | March to May | Ciudad de México, Tamaulipas | NO | NE | NE | |

| Flor de sotol | Asparagaceae | Dasylirion acrotrichum | N | Wild harvest (xeric shrublands) | 2, 4 | February | Puebla | A | NE | NE |

| Flor de palma | Asparagaceae | Yucca filamentosa | N | Wild harvest (xeric shrublands) | 1, 2, 3, 4, 8 | February to July | Aguascalientes, Nuevo León, Puebla | PR | NE | NE |

| Flor de sábila | Asphodelaceae | Aloe vera | I | Cultivated | 3, 8 | September | Puebla | NO | NE | NE |

| Garambullo | Cactaceae | Myrtillocactus geometrizans | N | Wild harvest (xeric shrublands) | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 | March to May | Puebla | NO | LC | Appendix 2 |

| Flor de calabacita | Cucurbitaceae | Cucurbita pepo ssp. pepo | N | Cultivated | 2, 3 | June to August | Chiapas, Guerrero, Oaxaca, Puebla, Veracruz | NO | NE | NE |

| Flor de calabaza grande | Cucurbitaceae | C. moschata | N | Cultivated | 2, 3 | August | - | NO | - | NE |

| Flor de madroño | Ericaceae | Arbutus xalapensis* | N | Wild harvest (pine-oak forest) | 4 | February to April | Chihuahua | PR | LC | NE |

| Flor de ayocote | Fabaceae | Phaseolus coccineus | N | Wild harvest (pine-oak forest) and cultivated | 4 | January, July to September | Chiapas, Puebla, Tlaxcala | NO | LC | NE |

| Pemuches or colorín | Fabaceae | Erythrina americana | N | Wild harvest (pine-oak forest) and cultivated | 4 | November to February | Estado de México, Guanajuato, Guerrero, Michoacán, Morelos, Nuevo León, Oaxaca, Puebla, San Luis Potosí, Tabasco, Veracruz | A | NE | NE |

| Flor de cuaresma | Eupphorbiaceae | Euphorbia radians | N | Wild harvest (pine-oak forest) | 4, 7 | March | - | NO | NE | NE |

Origin: N= native, I= introduced.

Cooking method: 1 = asados en el comal (roasted on the griddle), 2 = guisados a la mexicana (stewed Mexican-style), 3 = guisados en quesadillas (stewed, then added to quesadillas), 4 = tortitas con o sin caldillo de jitomates (savory pancake with or without tomato broth), 5 = capeados con o sin caldillo de jitomate (egg-battered, with or without tomato broth), 6 = as an additional ingredient of meat stews, 7 = added to salads, 8= with scrambled eggs. NOM-059: PR = subject to special protection, A = threatened, NO = not listed. IUCN: LC = least concern, NE = not evaluated. CITES: Appendix 1 = endangered species, trade is authorized only under special circumstances, Appendix 2 = species that are not necessarily endangered, trade should be controlled NE = not evaluated. *could also be the species A. bicolor.

Huauzontle.- These consist of the tender stems and tiny flower clusters with greenish petals of Chenopodium berlandieri subsp. nuttalliae. These were most often sold by the manojo (bundle), although there are other vendors who sell by weight (Figure 2A). They contain high contents of vitamins A, B, C, and E, as well as iron, phosphorus, and calcium (Román-Cortés et al. 2018). They are frequently prepared during the religious dates of Lent and Holy Week. All recipes begin with boiling them for a few minutes to eliminate bitter flavors. They are mainly prepared in a savory pancake with or without tomato broth, egg-battered with or without tomato broth, or used as an ingredient in salads.

Figure 2 Edible flowers commercialized in the local markets studied of Pachuca de Soto, Hidalgo, Mexico. A) Huauzontle, B) Gualumbos, C) Flor de sotol, D) Flor de palma, E) Flor de sábila (Photos CJ Figueredo-Urbina).

Gualumbos.- Their other common names include golumbos, flor de quiote or flor de maguey. In the Mezquital Valley, they are called nthembo (from the hñähñu language) and in other regions of the country are known as cacayas or bayusas. These flowers are collected from maguey manso or maguey pulquero (Agave salmiana and A. mapisaga). Once collected, all of the greenish-yellow flower buds are defoliated and cleaned, removing the pistil, stamens, and ovary, selling only the petals or tepals (Figure 2B). They are displayed in plastic bags weighing about 10 kg, and the sales unit is the tin or in plastic bags that contain one or two tins. They are also offered in fists or manitas, which are the clusters of the flowers or raceme that have not been cleaned. Other species of the genus are also consumed, such as A. marmorata in Puebla or A. inaequidens in Michoacán. These flowers provide fiber, protein, minerals, carotenoids, ascorbic acid and saponins (Sotelo et al. 2013, Pinedo-Espinoza et al. 2020). Saponins can have a bitter or spicy flavor, so the flowers are soaked or boiled for a few minutes at the beginning of their preparation. This was the flower for which the largest number of preparation methods were reported (six; Table 2).

Flor de sotol.- These are collected from the plant known as sotol or cucharilla (Dasylirion acrotrichum Zucc.). These flowers were rare (Figure 2C), and they were sold by the lata or puñado (handful) and in small quantities. The green-brown flower buds from the racemes are sold. We did not find records of the nutritional content of these flowers. In the Mezquital Valley, they are consumed in a sauce prepared with xoconostle (Opuntia joconostle F.A.C. Weber ex Diguet) (Peña & Hernández 2014).

Flor de palma.- This flower does not actually come from a palm, but rather from plants in the family Asparagaceae (Yucca filamentosa L., Figure 2D). In the stalls these flowers were displayed in 10 to 15 kg plastic bags and sold by the lata or puñado. The flowers are greenish-white in color and contain ascorbic acid, calcium and protein as well as saponins, (Peña & Hernández 2014, Pinedo-Espinoza et al. 2020), which give them a bitter and slightly spicy flavor, so they are soaked or boiled for a few minutes when preparing them. The vendors commented that exposing the flowers to the sun for a few hours eliminates the bitter taste.

Flores de sábila.- Aloe vera (L.) Burm.f. is not native to Mexico; it is native to Africa and was introduced to America by European contact and is now widely cultivated around the world (Figure 2E). The flowers were offered as manojos; its sale was rare and in low quantities. These flowers have high fiber content and medium protein content, contain minerals like phosphorus, and have low antioxidant activity (Pinedo-Espinoza et al. 2020).

Garambullos.- Also called clavel de garambullo, these are the flowers of the columnar cacti of the same name (Myrtillocactus geometrizans Console) (Figure 3A). These flowers have white petals, are delicate and wilt quickly. They were presented at market stalls in small open bags, sold by the lata or the bag. They contain high concentrations of potassium and calcium and have phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity (Pinedo-Espinoza et al. 2020). In the Mezquital Valley, they are the base of many dishes, such as sopa de frijol quebrado con garambullos, gorditas, quesadillas and scrambled eggs (Peña & Hernández 2014).

Figure 3 Edible flowers commercialized in the local markets studied in Pachuca de Soto, Hidalgo, Mexico. A) Garambullos, B) Flores de calabacita, C) Flores de madroño hembra, D) Flor de ayocote, E) Pemuches, F) Flores de cuaresma (Photos CJ Figueredo-Urbina).

Flor de calabacita.- Zucchini flowers (Cucurbita pepo ssp. pepo) were frequently commercialized in the market (Figure 3B). However, on one occasion one of the vendors offered large pumpkin flowers (C. moschata (Duchesne ex Lam. Duschesne ex Poir, 1818), both of which were sold by the manojo. The flowers are yellow and contain the precursor compounds of vitamins A and C, in addition to high levels of fiber, folic acid, riboflavin, niacin, and minerals such as calcium, phosphorus, iron and potassium (Sotelo et al. 2013).

Flores de madroño.- These are the flowers of the species Arbutus xalapensis Kunth (Figure 3C). They were transported in kitchen utensils such as strainers or plastic bags and sold by the lata. The flowers are bell-shaped, and two types of these flowers, differentiated by color, were identified: the white machos were more common than the pink hembras. The flowers have high levels of fiber and minerals, but low protein content (Sotelo et al. 2013).

Flor de ayocote.- These are the flowers of Phaseolus coccineus L., called ayocote, ayecote or ayocotli, Nahuatl root words. They were sold in plastic bags or by the puñado. They are red or orange in color due to their anthocyanin content, compounds which have antioxidant activity (Figure 3D). The traditional way of preparing these flowers is as tortitas en caldillo de jitomate (Table 2).

Pemuches or colorín.- These flowers are obtained from the tree Erythrina americana Mill. (Figure 3E). They were sold by the lata or puñado. The flowers are red and grouped in a cluster. The flower buds and open flowers are consumed, in both cases removing the pistils and stamens because they have a bitter taste. They are mainly prepared as savory pancakes (Table 2). The flowers contain bioactive compounds such as alkaloids, although in lower concentrations than the seeds of the plant, so they also have medicinal uses. They also contain high levels of calcium (Sotelo et al. 2013, Pinedo-Espinoza 2020). The flowering coincides with the religious celebration of Holy Week when people abstain from meat the consumption, and it is sometimes known as carne de vigilia (abstinence meat).

Flor de cuaresma.- These flowers are collected from Euphorbia radians Benth., an herb that reaches 25 cm in height (Figure 3F). These flowers are grouped in a structure called the cyathium, surrounded by bracts or pink hypsophylls, and are modified unisexual flowers. They were brought to the markets in plastic bags and sold by the lata. This flower is consumed during the celebration of Lent (cuaresma) and Holy Week, hence its name. The vendors identified two types of flowers, normal and large, determined by the size of the petals (bracts). These flowers are collected in shady places in the pine-oak forest. They have high protein and fiber contents (Sotelo et al. 2013).

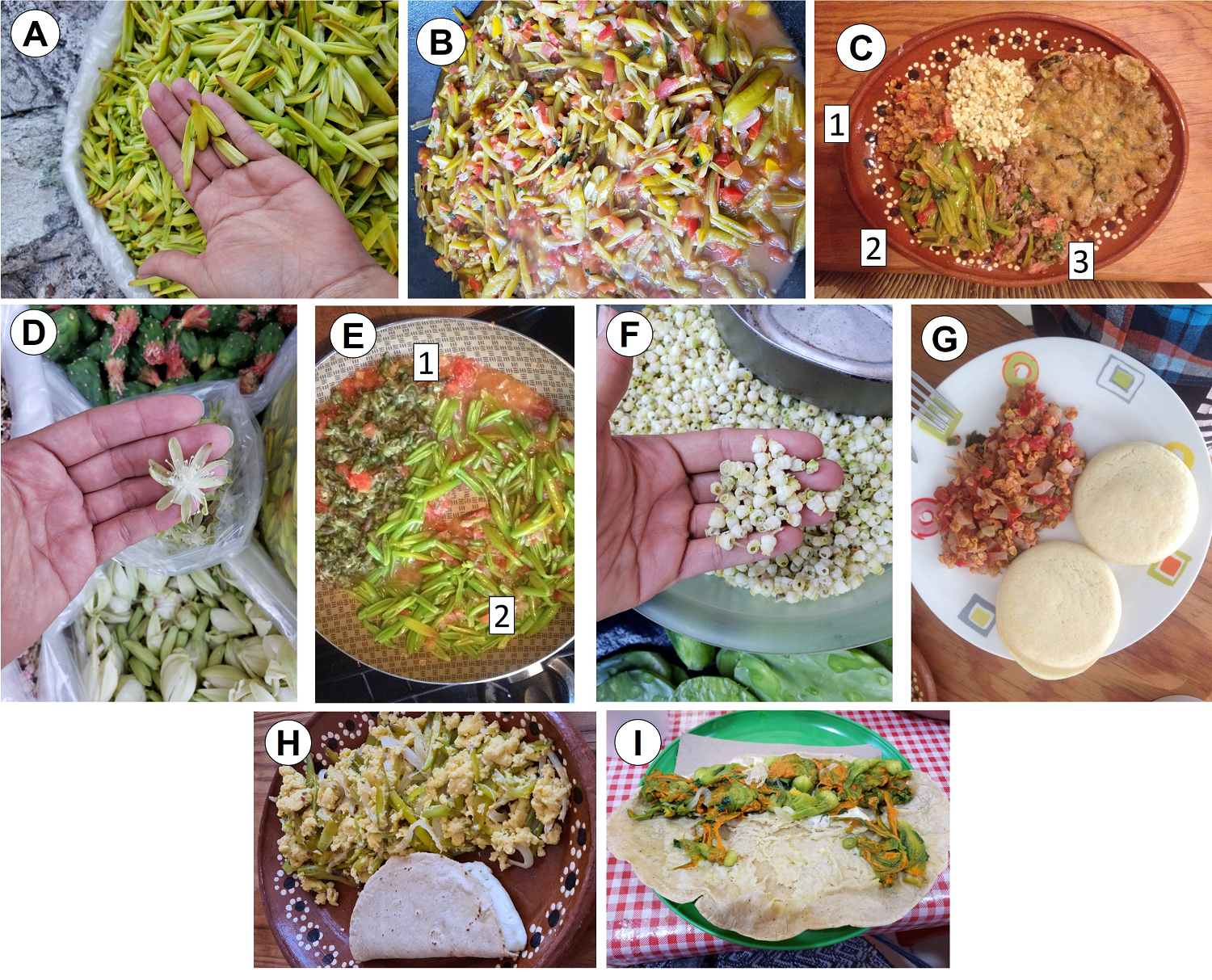

Recipes. Eight forms of flower preparation were recorded (Table 2, Figures 4, 5). Here we describe two of the recipes collected, which were the most frequently mentioned and that can be used to prepare most of the reported flowers.

Figure 4 Some of the culinary flower preparations recorded in this study: A) Fresh gualumbos ready to cook, B) Gualumbos cooked in the Mexican Style, C) Mexican Style flower preparations: 1) flores de madroño, 2) gualumbos, 3) garambullos, D) Fresh garambullos ready to cook, E) Flower preparation: 1) Mexican Style garambullos, 2) Roasted gualumbos with garlic and onion, F) Fresh flores de madroño macho, G) Mexican Style flor de madroño, H) Tacos with Mexican Style gualumbos with egg, i) Quesadilla de flor de calabacitas (Photos CJ Figueredo-Urbina, GD Álvarez-Ríos).

Figure 5 Some of the culinary flower preparations recorded in this study: A) Huazontles ready to cook, B) Tomato variety known as miltomate (Solanum lycopersicum), C) Dish of tortitas huauzontles con caldillo de miltomate, D) Fresh flores de ayocote, E) Tortitas de ayocote, F) Dish of tortitas de flor de ayocote with miltomate broth and rice. (Fotos C.J. Figueredo).

Gualumbos a la mexicana (Mexican Style Gualumbos).- Ingredients for 4 servings: 2 tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum), 1 medium white onion (Allium cepa), 2 tablespoons of your choice of oil, 1 serrano pepper (Capsicum annuum) (two, if you like it hotter), two latas of cleaned gualumbos (about 300 grams) and a few sprigs of coriander (Coriandrum sativum) or epazote (Dysphania ambrosioides). Preparation: 1) Bring water to a boil in a pot; once boiling, add the gualumbos and leave them for 5 minutes or until the color of the petals clears. 2) Remove from the heat and drain. 3) Clean and chop the onion. 4) In a frying pan add two tablespoons of oil and fry the onion. 4) Wash and chop the tomatoes, add them to the onions. 5) Wash and devein the chilies, chop, add to the pan, and stir. 6) Add the gualumbos, stir, and cook for 15 minutes over low heat, placing a lid on the pot. 7) Wash and chop the coriander or epazote, add to the mixture, salt to taste, turn off the heat, and cover. Serve in tacos, quesadillas, mixed with eggs, or added to meat stews (Figure 4A, B, C).

Tortitas de huauzontles con caldillo de miltomate (Savory Huauzontle pancakes in miltomate broth).- Ingredients for 4 servings: two manojos of huauzontles (280 grams approx.), 4 eggs, ½ cup of wheat flour, 1 teaspoon of baking powder, 2 lata of tomatoes (S. lycopersicum), ½ onion (A. cepa), a few sprigs of epazote (D. ambrosioides), oil for frying. Optional: cumin (Cuminum cyminum), pepper (Piper nigrum) and chili (C. annuum). Preparation for the broth: 1) Boil the whole tomatoes for five minutes. 2) Remove from the heat, let cool, blend whole with a small amount of the boiling liquid, and set aside. Preparation of the savory pancakes: 1) Separate the huazontle flowers from the main stem, place in a bowl. 2) Add the eggs and beat. 3) Sift the flour and add to the mixture along with the teaspoon of baking powder and beat. 4) Add salt, pepper, and/or cumin. 5) Add plenty of oil in a frying pan; when the oil is hot, take ¼ cup of the mixture and fry on both sides. 6) Drain the savory pancakes on absorbent paper. 7) Heat the tomato sauce, wash and chop the epazote and add to the sauce, stir, turn off the heat, and cover. To serve, place the tortitas in a bowl and add the broth (Figure 5A, B, C).

Risk and conservation categories. Of the 13 species recorded in this study, four appear in Mexico’s conservation legislation, NOM-059 (SEMARNAT 2010); two are in the category of Subject to Special Protection (PR): flor de madroño (Arbutus xalapensis) and flor de palma (Yucca filamentosa). These species could increase their risk status if the factors that negatively affect their viability are intensified. The other two species are in the Threatened category (A), pemuches (Erythrina americana) and flor de sotol (Dasylirion acrotrichum), which could be in danger of disappearing in the short or medium term if habitat deterioration or modification continues or the size of their populations decreases. On the IUCN (2020) red list, four species were listed in the least concern category (LC)-the gualumbos (Agave salmiana), flor de madroño (Arbutus xalapensis), garambullo (Myrtillocactus geometrizans) and flor de ayocote (Phaseolus coccineus), therefore their populations are not considered seriously affected, the rest are not evaluated. The only species that was classified in Appendix II of CITES was Myrtillocactus geometrizans; while the wild populations are not threatened by extinction, they suggest that the sale of these flowers is subject to regulation.

Discussion

The edible flowers in these markets were mainly commercialized by women, as has been reported by De la Peña & Illsley (2001) in other regions of the country. Other studies in Europe indicated that gathering of plants was usually regarded as an activity for women (Pieroni 1999, Christanell et al. 2010). The studies that have been carried out on food in Mexico have made it possible to highlight the importance of women, and particularly indigenous women, in the transmission of knowledge from generation to generation, which ranges from instruments for collecting food, to the transport to the house and the markets for their sale, to the methods for preparing these products. In this study, even though it is a local market in the main city of the state, we show that indigenous women play a fundamental role in maintaining the knowledge and tradition around edible flowers.

For the species documented in this study, we found 59 records in BADEPLAM, record of its consumption in 16 states of the Mexico (Table 2). No records were found for the species Cucurbita maxima and Euphorbia radians. Specifically, for the state of Hidalgo, there were 38 BADEPLAM records that included 30 plant species belonging to 15 botanical families whose flowers are consumed or used in culinary preparations as colorants or flavorings for beverages (Table 3). The numbers of flowers that are commercialized in the local markets of Pachuca de Soto is about 20 % of the number of flowers consumed nationwide (according to Mapes & Basurto 2016) and in the state (according to the records in BADEPLAM). We can comment that the differences in the number of edible flowers registered for the state (according BADEPLAM) and those registered in this study, could be due to: a) low availability of the resource (of some particular species), b) difficulty of collecting the resource, d) low demand in the markets, and/or e) very local or traditional consumption. It may also be due to the scale of the studies, that is, a greater number of markets and different bibliographic sources. Furthermore, the number of edible flowers recorded in this study was lower than those recorded in traditional markets in Oaxaca (n = 17), where Huazontles, Flor de calabacitas and Flor de Ayocote were also sold.

Table 3 Recorded plant species for the state of Hidalgo whose flowers are consumed or used as flavorings and dyes in various traditional culinary preparations. Source: 1) this study and 2) BADEPLAM.

| Family | Species | Common Name | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amaranthaceae | Chenopodium berlandieri subsp. nutalliae | Huahquilitl, tlahuahquilitl, huauzontle | 1, 2 |

| Asparagaceae | Agave americana | Maguey blanco | 2 |

| A. applanata | Maguey cenizo | 2 | |

| A. lechuguilla | Amole | 2 | |

| A. salmiana* | Maguey manso | 1, 2 | |

| A. striata | Tha'mni | 2 | |

| Dasylirion acrotrichum | Sotol, manita | 1, 2 | |

| Nolina parviflora | Palma | 2 | |

| Yucca filifera | Palma | 1, 2 | |

| Y. gigantea | Izote | 2 | |

| Asphodelaceae | Aloe vera | Sábila | 1 |

| Cactaceae | Myrtillocactus geometrizans | Garambullo | 1, 2 |

| Convolvulaceae | Ipomoea stans** | Pexpo | 2 |

| Crassulaceae | Sedum goldmanii | Chisme | 2 |

| Cucurbitaceae | Cucurbita moschata |

Ra demu Calabaza grande |

1, 2 |

| C. pepo | Calabacitas | 1 | |

| Ericaceae | Arbutus xalapensis | Madroño | 1, 2 |

| Arctostaphylos pungens | Madreselva | 2 | |

| Euphorbiaceae | Cnidoscolus multilobus | Ortiga, totopo | 2 |

| Euphorbia radians | Cuaresma | 1 | |

| Fabaceae | Erythrina americana | Pemuches, colorín, quiquimite | 1, 2 |

| Leptospron adenanthum | Ra thengabonju | 2 | |

| Prosopis laevigata | Mezquite | 2 | |

| Phaseolus coccineus | Ayocote | 1,2 | |

| Marcgraviaceae | Souroubea exauriculata | Ra donts'andämmbe | 2 |

| Orobanchaceae | Castilleja moranensis | Hierba del conejo de llano | 2 |

| Conopholis alpina | Mazorca de zorra | 2 | |

| Rubiaceae | Bouvardia longiflora | Flor de San Juan | 2 |

| Solanaceae | Physalis coztomatl | Guarumbo | 2 |

| Violaceae | Viola painteri | Clavelito de campo | 2 |

*flavoring; **only dye

Squash flowers are the most consumed edible flower in Mexico. They are produced on a larger scale and sold in markets throughout the country, and in local markets in other regions of Mexico, the flowers of the pipiana squash (C. argyrosperma C. Huber) and chilacayote (C. ficifolia Bouché) are also consumed.

A larger number of flowers were marketed during the season of Lent, since flowers represent a food option for this time of year when meat consumption is limited in the case of the Catholic religion.

The large volumes of Gualumbo flowers that are offered in the markets suggest that there is high demand, and larger volumes are sold weekly than other flowers. This fact may be because Agave plants produce an inflorescence with a large number of flowers (up to 12 kg), which may be more profitable for sellers and be easier to collect (Figueredo 2020). In this sense, the collection of wild plants differs in the amount collected when it is for self-consumption from those that are used for commercial purposes, where significant volumes are harvested (Blancas et al. 2020). For the Gualumbos it has been recorded that the collection for commercialization can become aggressive, including cutting the entire floral scape, compared to the self-consumption in which the form of collection is less aggressive and of lower quantities, since only the amount that will be consumed is taken on a given day (Figueredo 2020). However, for these flowers and other genetic resources, there is a lack of information on the consequences of this use to self-consumption and commercialization (Blancas et al. 2020, Figueredo 2020)

The consumption of flowers in Mexico is an activity that was already the custom of the people present before Spanish colonization (Sotelo et al. 2013). Currently, the activity is maintained and is becoming more and more popular in avant-garde gastronomy. There are important cookbooks that collect cultural information about edible flowers and their recipes, as part of the safeguarding of this national heritage. This list includes “Las flores de la cocina mexicana” which compiles 122 recipes of approximately 35-40 different types of flowers, mostly native (except for the Rosas (Rosa spp. L., 1753), Sábila (A. vera) and Flores de Plátanos (Musa x paradisiaca L.) (Torres 2014). We also find the work of Sánchez (2017), “Las flores en la cocina Veracruzana” with 163 recipes of 40 flower species, which also includes the previously mentioned non-native species and the flores de Azahar (Citrus spp. L., 1753), Jamaica (Hibiscus saddariffa L., 1753), flor de haba (Vicia faba L., 1753), Framboyan (Delonix regia (Bojer ex Hook.) Raf.), flor de sacramento (Calathea marantifolia Standl.) and Gardenias (Gardenia jasminoides J. Ellis). Particularly for the state of Hidalgo, there is the book “Tradiciones de la cocina hñähñu del Valle del Mezquital” (Peña & Hernández 2014), which includes a total of 281 recipes, where 61 correspond to recipes with flowers of approximately 28 different taxa, either as the main ingredient or a secondary ingredient in the dish.

Flowers have been important elements of traditional cuisine worldwide, both in ancient times and today. For the South American region, data on edible flowers are scarce or non-existent. Recently, in the work of Clement et al. (2021), information is given on plants with edible uses in the Central Andes region (n = 424) and lowlands (n = 1719), but it is not specified how many correspond to edible flowers. Some works have carried out investigations that evaluate the nutrient content in flowers. In China, Zheng et al. (2018) and Li et al. (2014), have evaluated the antioxidant capacity of more than 60 species of flowers. In western Assan, India, 31 species of edible flowers have been recorded (Deka & Nath 2014), which contrasts with the records for the Mandal-Chopta Forest in Uttarakhand, India, where only five were recorded (Agarwal & Chandra 2019). The research of Khomdram et al. (2019) documented 59 species of edible flowers that are consumed by indigenous people of Mizoram in the Northeast of India.

In the Valais region of Switzerland, 98 species of traditionally consumed wild plants have been identified where the main part of the plant consumed is the flower (26 %) of 22 species, mainly prepared in teas (Abbet et al. 2014). Guiné et al. (2019), in Portugal, found that edible flowers have little tradition among the population and the main form of preparation is in drinks, while traditional dishes do not mention flowers as part of their ingredients, with the exceptions of cauliflower, broccoli and artichoke. However, in the northwest of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) flowers are consumed from 9 of the 97 species of edible plants (de Santayana et al. 2007). In the Mediterranean region of Garfagnana, Italy, 113 wild plants consumed as food have been recorded, of which only four correspond to flowers (Pieroni 1999). These data from various regions of the world reflect the high global diversity of edible flowers, which in some cases coincides with the numbers recorded in Mexico. This type of research is relevant in the context of food security, since it allows the identification, documentation and dissemination of information on edible flower species that offer affordable options for human nutrition (Takahashi et al. 2019). Unfortunately, with globalization and population growth, eating habits such as fast food has been adopted, mainly among the young population, which in part seem to be leading to the disappearance of knowledge about the traditional and cultural use of edible flowers. Rescuing this knowledge is a way of exploring the dietary diversity and the economic potential that wild species of edible flowers provide, preserving biodiversity and traditional knowledge (Takahashi et al. 2019, Harmayani et al. 2019).

It is important to highlight that edible flowers are a genetic resource with great economic and medical potential. An excessive demand for these resources would generate overexploitation, affecting the size and viability of their populations, as well as altering the biotic interactions with other organisms that sustain these resources (López 2008). For example, gualumbos are a valuable food resource for a wide spectrum of visitors including insects, birds, and bats. Intensive collection could reduce the number of flowers, affecting the populations of all of these species and of these plants themselves. The impacts of the overexploitation of these genetic resources could occur at three scales: 1) reduction or loss of the genetic diversity of the plant due to extraction or impeding sexual reproduction and dispersal of seeds of a certain genotype, 2) demographic impacts from the reduction or extinction of populations and 3) impacts on ecological communities and interaction networks with the loss of ecosystem functions and processes (Hall & Bawa 1993, López 2008). The increase in the commercialization and consumption of some flowers could lead to their decrease, which would affect the species, the ecosystems where they are found and the communities that use them.

This depletion of the resource could be an underlying cause of loss of diversity or lead to species being placed in alarming categories such as endangered (Broad et al. 2003, Stewart 2003). Furthermore, the overexploitation of the resource may lead to the economic decline of the families of managers and vendors themselves, who depend on the economic income from the sale of these resources.

For the most part, for the genetic resources commercialized in the markets studied, the total quantities sold and current state of the wild populations under extraction are unknown. Likewise, social aspects of harvesting are not known, such as the precise practices of obtaining flowers, the contribution to the family economy of the sale of flowers, and the cultural motivations that influence the sale of certain flowers over others. It is necessary to generate this type of information so that the status of these resources can be evaluated through social and ecological indicators in order to propose sustainable management and conservation plans (Sheil & Wunder 2002).

Edible flowers are an important genetic resource, providing economic income to vendors, and the diversity of their preparation reflects the great traditional knowledge of these groups. Despite the fact that the majority of the recorded species are not currently in risk categories, they are frequently collected from natural ecosystems and are the reproductive part of the plant, so an increase in demand could have consequences for the long-term permanence of these plants. However, before establishing management and conservation strategies, the ecological and demographic status of these genetic resources must be documented. Their ecological importance is added to their cultural importance, since edible flowers are an important source of nutrients and part of the cultural identity of indigenous and mestizo groups, both in rural contexts where they are obtained and in urban contexts where they are commercialized.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)