Celastraceae sensu lato is a subcosmopolitan family composed of ca. 98 genera and 1,211 species. The most recent classification of Celastraceae proposed by Simmons (2004) is strongly supported by molecular data (e.g., Simmons & Hedin 1999, Simmons et al. 2001a, b, Islam et al. 2006, Zhang & Simmons 2006, Coughenour et al. 2010, 2011). It recognizes three monophyletic subfamilies: Hippocrateoideae, Salacioideae and Stackhousioideae, each one derived independently from Celastroideae, which is paraphyletic.

Traditionally, Celastraceae has been recognized as a morphologically variable group where the inclusion of some taxa is controversial. This problem has been particularly highlighted in its fossil record (Estrada-Ruiz et al. 2012, Bacon et al. 2016, Zhu et al. 2020). Since fossils rarely are preserved as complete plants or in organic connection their identification and classification is restricted and doubtful in comparison to extant plants (Nixon 1996, Crepet 2008). Despite its inherent limitations, the fossil record has become highly relevant in supporting or refuting evolutionary scenarios including the dating of clades (Donoghue & Benton 2007, Parham et al. 2012, Magallón et al. 2015). Therefore, the availability of a reliable fossil record is crucial since errors in phylogenetic analyses have resulted from incorrect identifications and/or incorrect age assignments to fossil material (Parham et al. 2012).

According to the most recent revision of Celastraceae by Bacon et al. (2016), the family has an extensive fossil record. However, many of the fossils do not show diagnostic characters or their descriptions lack enough detail to consider them as reliable reports. Nevertheless, several newly published records are relevant for the history of the family (e.g., Chambers & Poinar 2016, Franco 2018).

Therefore, our objective is to build on previous work by providing a review of the Celastraceae fossil record in order to establish reliable reports, which can potentially be used to calibrate molecular clocks.

Material and Methods

Revision of literature. We evaluated a total of 168 reports of fossils with affinity to Celastraceae or referred to the family, covering publication dates from 1869 to 2018. The reports of this revision were published in specialized literature and include the original descriptions (see Supplementary Material, Table S1).

The consistency of the identification of the Celastraceae fossils was determined considering the criteria proposed by Martínez-Millán (2010), which are mentioned in order of decreasing reliability: (1) inclusion of the fossil in a phylogenetic analysis, (2) discussion of key characters to place fossils in the group, (3) list of characters to include the fossil in a certain group, (4) complete description and diagnosis of the fossil, (5) photographs of the specimen, (6) drawings, diagrams and reconstructions of the fossils, (7) specimen information, home institution, collection number, and holotype designation, (8) collection information; locality, formation, and age. Manchester et al. (2015) indicated that the system proposed by Martínez-Millán (2010) is questionable since criteria (2) and (3) include similarities without indicating if they are unique and/or constitute a synapomorphy. For this reason, we included a discussion of these points. Furthermore, the selected fossils correspond to the oldest ones within the linage (Donoghue & Benton 2007, Parham et al. 2012), which is based on the Global Stratigraphic Chart 2020 (Cohen et al. 2020). Finally, the phylogenetic position of each fossil was established according to its comparison to extant taxa, recognizing that their similarity suggests a relationship between them (Wiens 2003, Sauquet et al. 2012).

Results

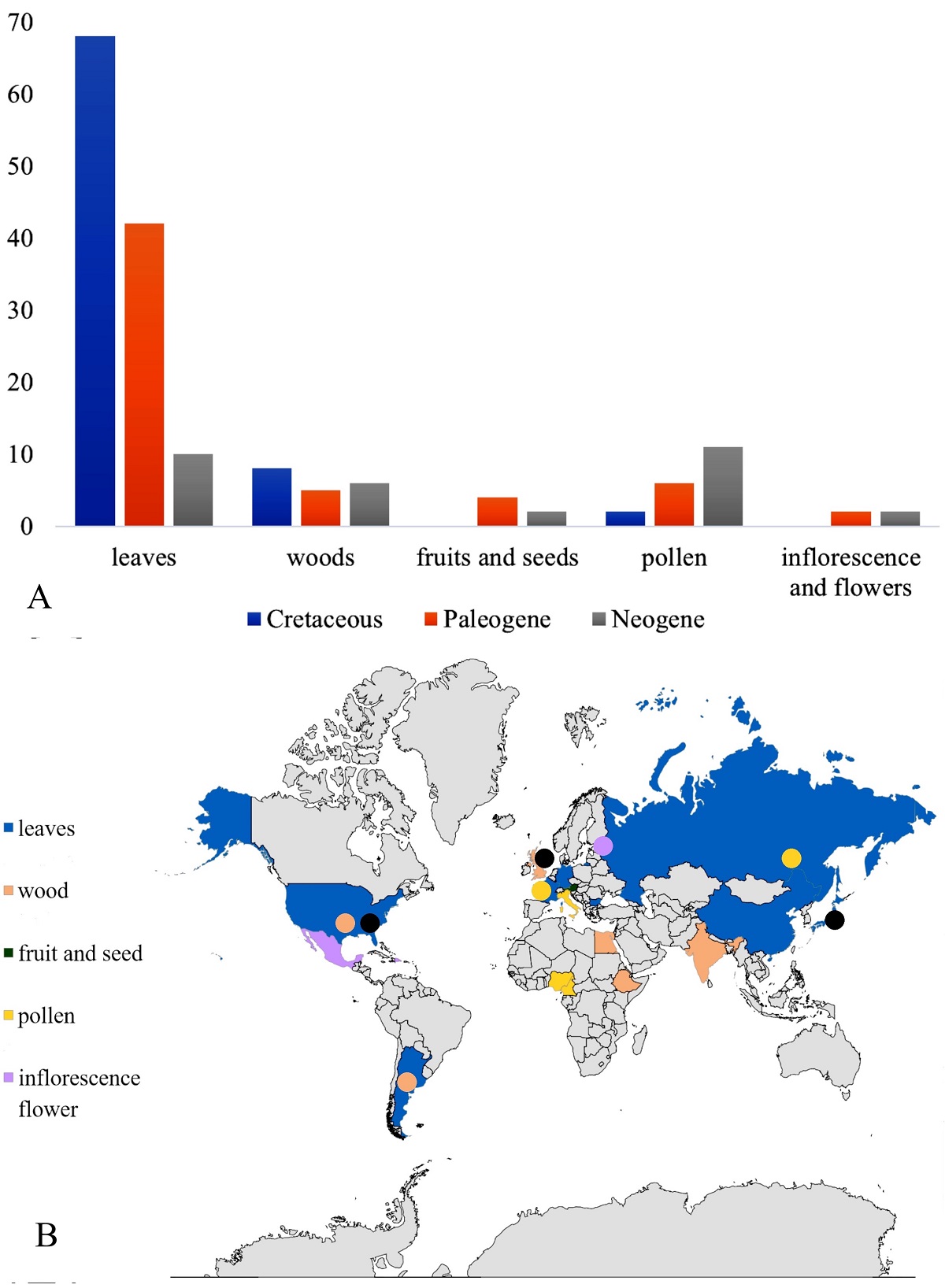

A total of 168 records were found, of which 139 are vegetative, with 120 leaves and 19 woods. They have a temporal range that extends from the Cenomanian (Cretaceous) to the Pliocene (Neogene). Likewise, the record of reproductive structures that includes pollen (19), fruits and seeds (6), as well as inflorescences and flowers (4) have been recognized from the Maastrichtian (Cretaceous) to the Pliocene (Neogene) (Figure 1A, B).

Figure 1 A. Abundance of leaves, woods, fruit-seeds, pollen, inflorescences, and flowers fossils assigned to Celastraceae by geologic time. B. Map showing the distribution of fossilized organs of plants identified as a member of Celastraceae.

In the next paragraphs, we discuss fossil taxa identified through vegetative and reproductive organs. Each one of them has a brief introduction and a discussion of the character or character set that supports their inclusion in Celastraceae. The results are summarized in Table 1 with nine fossil record recognized here as reliable (see Supplementary Material, Table S2). Figure 2 displays the phylogenetic positions of each one based on the topology reported by Coughenour et al. (2010).

Table 1 Fossils records proposed as molecular clock calibration points arranged in alphabetic order. *Absolute age is available.

| Fossil name | Plant part | Geological Age (Ma) |

System Series | Provenance | Reference | Relationship-Compared to |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baasia armendarisense | wood | 73.5* | Upper Cretaceous | McRae Formation, USA | Estrada-Ruiz et al. 2012 | Cassine |

| Cathispermum pulchrum | fruit and seeds | 33.9 | Eocene | London Clay, England | Reid & Chandler 1933 | Catha edulis |

| Celastrus comparabilis | leaves | 33.9 | middle Eocene | Kushtaka Formation, USA | Wolfe 1977 | Celastrus |

| Elaeodendroxylon sp. | wood | 33.9 | Eocene | Braunkohlen-Tagebau, Germany | Gottwald 1992 | Elaeodendron |

| Hippocrateaceaedi-tes sp. | pollen | 33.9 | Eocene | Laki Basin, India | Venkatachala & Kar 1969 | Loseneriella |

| Lobocyclas anomala | flower | 23-30* | middle Oligocene-lower Miocene | Dominican Republic | Chambers & Poinar 2016 | Prionostemma, Hippocratea |

| Maytenoxylon perforatum | wood | 5.3 | Miocene | Ituzaingó Formation, Argentina | Franco 2018 | Maytenus |

| Salacia lombardii | flower | 23-15* | middle-early Miocene | Simojovel de Allende, Mexico | Hernández-Damián et al. 2018 | Salacia |

| Wuyunanthus hexapetalus | flower | 66.0-61.6* | lower Paleocene | Wuyun, China | Wang et al. 2001 | Euonymus, Celastrus |

Figure 2 Assignment of Celastraceae fossils as molecular clock calibration points based on topology of Coughenour et al. (2010). 1. Baasia armendarisense (Estrada-Ruiz et al. 2012), 2. Cathispermum pulchrum (Reid & Chandler 1933), 3. Celastrus comparabilis (Wolfe 1977), 4. Elaeodendroxylon sp. (Gottwald 1992), 5. Hippocrateaceaedites sp. (Venkatachala & Kar 1969), 6. Lobocyclas anomala (Chambers & Poinar 2016), 7. Maytenoxylon perforatum (Franco 2018), 8. Salacia lombardii (Hernández-Damián et al. 2018), 9. Wuyunanthus hexapetalus (Wang et al. 2001).

Leaves. Leaves are the most abundant fossil record of Celastraceae (Bacon et al. 2016). These have been related to extant members of Celastroideae (Simmons 2004) and they are widespread in strata of Cretaceous and Paleogene (Figure 1A). The fossil leaves of Celastraceae represent artificial forms because they had been described under strictly morphological criteria (Dilcher 1974). Celastrophyllum (Göppert 1854) and Celastrinites Saporta (Saporta 1865) represent extinct genera of Celastraceae that had been compared with Celastrus. They are mainly distributed in Europe (e.g., Vachrameev 1952, Samylina 1968, 1984) and high latitudes in America (e.g., Lee & Knowlton 1917, Knowlton 1919, 1922, Berry 1925). Doweld (2017) noted that there are two more descriptions associated with Celastrophyllum: Celastrophyllum Ettingsh. ex Saporta & Marion, and Celastrophyllum Ettingsh. ex Schimp.

Upchurch & Dilcher (1990) suggested that the type species of the genus should be Celastrophyllum attenuatum Göpp. It was described as a leaf with an entire margin and distinctive petiole, causing the expansion of the Celastrophyllum concept to include entire and toothed leaves, an apparently logical aspect since Celastrus has extreme foliar variation (Upchurch & Dilcher 1990, Mu et al. 2012, Liang et al. 2016). These include for example, the shape of the lamina ranging from elliptical to oblong or broadly ovate to orbicular; apex acute to obtuse or round and base rounded to acute (Bacon et al. 2016); however, morphologies overlap at intra and interspecific levels (Mu et al. 2012).

Recently, Herendeen (2020) suggested that Celastrophyllum obtusum Heer. is the species that validates the name Celastrophyllum, but its typification is necessary. Unfortunately, none of the three reports of Celastrophyllum are valid. Several of these reports are probably part of other families or genera since they have no diagnostic characteristics of the group (Doweld 2017, Herendeen 2020). Other members of Celastraceae have been reported from the Paleogene, including Maytenus (Berry 1938, Rüffle & Litke 2008) and Euonymus (Berry 1924, Brown 1937). Despite this, these records are also unresolved, because they are morphologically indistinguishable (Mu et al. 2012).

A diagnosis based on the foliar architecture of Celastraceae was proposed by Hickey & Wolfe (1975). Based on this, the leaves of Celastraceae sensu stricto typically have a theoid tooth, which has a median vein. This vein runs toward the apex and expands on the tooth, so that the apex is covered by an opaque deciduous seta. Moreover, brochidodromous secondary veins as well as percurrent tertiary veins are common in the group (Hickey & Wolfe 1975). Subsequently, Upchurch & Dilcher (1990) indicated that all these characters are enough evidence to establish the identification of fossil leaves to Celastrus. More recently, Liang et al. (2016) indicated that the secondary venation of Celastrus varies from camptodromous to craspedodromus and semicraspedodromus types. Fossil leaves of the middle Eocene from the Green River Flora, USA, described by Hollick (1936) and reexamined by Wolfe (1977) are considered reliable records of Celastrus (Upchurch & Dilcher 1990).

Woods. Celastraceae often has woods with small, numerous and solitary vessels with simple or scalariform perforation plates; alternate bordered intervascular pits; and parenchyma variable in type and quantity, that sometimes can have scattered or even absent (Metcalfe & Chalk 1983). Additionally, the presence or absence of scalariform perforation plates is an informative character for the generic delimitation within the family (Archer & van Wyk 1993).

Family has few reports of fossil woods with Cretaceous age, and most of them are from Africa, Egypt, Ethiopia, and North America (Figure 1). As well as fossil leaves, the fossil record of woods have been related to extant genera of Celastroideae. For example, Celastrinoxylon (Schenk) Kräusel was identified by Schenk (1888) and reexamined by Kräusel (1939) (e.g., Kräusel 1939, Schӧnfeld 1955, Poole 2000, Kamal El-Din et al. 2006). It was recognized as a fossil wood with simple perforation plates, small vessels and rays composed entirely of square or erect cells, nevertheless, it has doubtful records. Such is the case of a fossil wood of Celastrinoxylon from India (Ramanujam 1960), which was reexamined and reassigned to Ailanthoxylon (Simaroubaceae) by Awasthi (1975). Additionally, Kamal El-Din (2003) described Celastrinoxylon as a wood with scalariform perforation plates from the Cretaceous of Egypt, but it contrasts to the diagnosis proposed by Kräusel (1939).

According to Poole & Wilkinson (1999)Celastrinoxylon has more resemblance to Catha because both have small vessels, simple perforation plate, tiny intervascular pits with an opposite arrangement, thin-walled fibers, and uniseriate rays with erect cells. This combination of characters differs from Celastrus, which has vessel dimorphism, broad rays, and other forms of the parenchyma commonly present in scandents and lianas (Carlquist 1988).

Other fossil taxa that have a simple perforation plate are Lophopetalumoxylon (Mehrotra et al. 1983) and Maytenoxylon (Franco 2018). The first one is characterized by the presence of diffuse porosity, solitary vessels, bordered and alternate intervascular pits, thin apotracheal bands of parenchyma, uniseriate homocellular rays, non-septate thick-walled fibers, and intercellular canals. Lophopetalumoxylon was compared closely to Lophopetalum, which commonly has multiple radial vessels (Mehrotra et al. 1983). Wheeler et al. (2017) suggested that Lophopetalumoxylon probably belongs to Sapindales since its features occur in other families.

On the other hand, Maytenoxylon is a wood with diffuse porosity, mainly solitary vessels, intervascular pits that vary from alternate to opposite, bands of fiber resembling parenchyma that alternate with ordinary fibers, both non-septate and septate ones, diffuse and scanty parenchyma, homocellular rays with some perforated cells (Franco 2018). The identification of Maytenoxylon is supported by the presence of perforated ray cells, which are restricted to Maytenus (Joffily et al. 2007).

Scalariform perforation plates have been rarely reported in the family (Metcalfe & Chalk 1983, Archer & van Wyk 1993), such is the case of Elaeodendroxylon (Gottwald 1992). It has been closely compared to extant Elaeondrendron because both have growth rings and numerous isolated or multiple radial vessels. Baasia (Estrada-Ruiz et al. 2012) is another taxon with a scalariform perforation plate. It has been considered as the most reliable record of Celastraceae until now, but its relationship to an extant taxon has not been established (Bacon et al. 2016).

Pollen. Celastraceae has spheroidal oblate or prolate radially symmetrical, isopolar, tricolporate pollen grains, and endoaperturate monads that are generally elongated and sometimes oblong (Bogotá & Sánchez 2001). Typically, three types of pollen grains have been recognized in the family: (1) polyads in groups of four tetrads, (2) simple tetrads and (3) monads (Erdtman 1952, Campo & Hallé 1959, Hallé 1960, Hou 1969, Lobreau-Callen 1977). All types have been recognized in the fossil record.

According to Ding Hou (1969) polyads and/or tetrads are common in Hippocrateoideae, Salacioideae, and Lophopetalum. For example, Salard-Cheboldaeff (1974) described Polyadopollenites macroreticulatus, P. microreticulatus and P. micropoliada from the Miocene of Cameroon as polyads of sixteen pollen grains, each one of them lacking an annulus and cross-linked exine, characters that are comparable to Hippocratea volubilis and H. myriantha. However, Polyadopollenites is a morphogenus assigned to circular and oval polyads, variable symmetry accounts for the aggrupation of sixteen monads, but it has been related with Fabaceae (Barreda & Caccavari 1992).

Furthermore, tetrads identified as Triporotetradites campylostemonoides, T. hoekenii, T. letouzeyi, and T. scabratus (Hoeken-Klinkenberg 1964, Salard-Cheboldaeff 1974, 1978, 1979) have been related to Campylostemon; however, similar tetrads are common in other families (Copenhaver 2005). Retitricoporites is another tetrad described by Salard-Cheboldaeff (1974) based on its tricolporate pollen grains with apparent endexin, whose morphology is close to Loseneriella.

Finally, Muller (1981) reported tricolporate monads recognized as Microtropis and Peritassa from the Oligocene of France (Lobreau-Callen & Caratini 1973). Additionally, Ramanujam (1966) assigned tricolporate pollen grains with elongate ectoapertures to Hippocrateaceaedites, it was latter recognized from the Eocene of India by Venkatachala & Kar (1969).

Fruits and seeds. Celastraceae exhibits a substantial morphological variation in fruits and seeds. Traditionally these have been used to subdivide the family taxonomically (e.g.,Loesener 1942, Takhtajan 1997, Cronquist 1981). According to Simmons et al. (2001a) the fruits can be capsules (with great variability in forms and types of dehiscence), schizocarpal mericarps (Stackhousiaceae), berries (e.g., Cassine, Maurocenia), drupes (e.g., Acanthothamnus, Elaeodendron), walnuts (e.g., Mortonia, Pleurostylia) or samaras (e.g., Rzedowskia, Tripterygium). Seeds are 1-12 in number, smooth or occasionally furrowed, albuminous or exalbuminous, sometimes winged, and the wing may be membranous or basal, exarillate or aril basal to completely enveloping the seed, and this can be membranous, fleshy, or rarely mucilaginous (Ma et al. 2008).

Reproductive organs have diagnostic characteristics, for this reason they have a high degree of reliability in taxonomic work and are highly useful for plant identification (Tiffney 1990, Wiens 2004). Berry (1930) described a loculicidal capsule with three rough leaflets as Celastrocarpus from the Eocene of Tennessee. As well as, Euonymus was tentatively assigned to a dehiscent capsule with four round lobes and separated by a sinuate sulcus (Berry 1930). Likewise, Euonymus moskenbergensis a fruit with five lobes from the Miocene of Australia was reported by Ettingshausen (1869). Fruits with seeds from the early Eocene (52-49 Ma) were reported by Reid & Chandler (1933) in the London Clay Formation (United Kingdom). These reproductive structures were described as small, subovoid and lobate fruits, containing seeds with a winged extension. In the same work, Canthicarpum celastroides was recognized as a loculicidal capsule with three leaflets and seeds whose testa has three layers, the outermost composed of large polygonal cells, and a fourth layer interpreted as a possible aril.

Tripterygium kabutoiwanum from the Pliocene of Japan (Ozaki 1991) was described as composed of winged fruits and leaves closely comparable with Tripterygium regelii. We were not able to obtain the original publication; however, other fossil records of the genus have been reexamined and assigned to Craigia (Malvaceae) (Kvaček et al. 2005, Manchester et al. 2009).

Flowers. The flowers are generally bisexual, with a conspicuous nectarial disk, five or fewer stamens immersed in the ovary (Stevens 2001). However, this general pattern is modified within the lineage, because the number of parts of the floral whorls, or merism, has been changed in some members (Matthews & Endress 2005). For example, flowers with a pentamerous perianth and a trimerous androecium are common in Hippocrateoideae and Salacioideae. It has been considered as a distinctive pattern in Celastraceae (Ronse De Craene 2010, 2016). Even more, modifications in the number of stamens have been reported in Salacioideae. Flowers with five (e.g., Cheiloclinium anomalum) or two (e.g., Salacia annettae and S. lebrunii) (Hou 1969, Hallé 1986, 1990, Coughenour et al. 2010) stamens are well known, and each type had an independent origin (Coughenour et al. 2010).

There are few records of fossil flowers of Celastraceae, among them the oldest one is Celastrinanthium hauchecornei, a cymose inflorescence preserved in Baltic amber (Conwentz 1886). According to Conwentz (1886) it includes bisexual flowers with a differentiated perianth with four sepals and petals, a disk, and an ovary with four locules. Other flower reports include Wuyunanthus hexapetalus from the Paleocene of China (Wang et al. 2001), Lobocyclas anomala (Hippocrateoideae) preserved in Miocene amber from the Dominican Republic (Chambers & Poinar 2016), and Salacia lombardii (Salacioideae) from Miocene of Simojovel de Allende, Mexico (Hernández-Damián et al. 2018). All these records have the general structural pattern of the family as they are bisexual flowers with a biseriate perianth and a conspicuous disk (Stevens 2001, Simmons 2004).

Discussion

Fossil record of Celastraceae has been recognized in the early scientific literature. It has abundant and diverse fossil evidence, but only a few records have enough information to be recognized as credible records. They are relevant in comparative analysis as dated phylogenies since these provide important information for the inference of the origin and diversification of a lineage. Different origin ages of the crown group Celastraceae have been estimated as 71.6 Ma (Magallón & Castillo 2009), (89) 76-71(60) Ma (Bell et al. 2010) and (109.85) 92.61 (76.98) (Magallón et al. 2015), but none of these analyses had as their main objective the family Celastraceae.

The most recently dated phylogeny of Celastraceae was proposed by Bacon et al. (2016). This work is relevant because it includes a revision of the fossil record of Celastraceae. But does not include newly reported fossil taxa that can change the phylogenetic interpretations when considering such taxa as Maytenoxylon perforatum (Franco 2018), Lobocyclas anomala (Chambers & Poinar 2016), and Salacia lombardii (Hernández-Damián et al. 2018).

In this revision, we recognize nine fossil records of Celastraceae as potential calibration points as each one represents the oldest age recognized for a lineage to date (Table 1). Most of these fossils have an age established through correlation rather than direct dating. Therefore, it is necessary to consider that these could change in the future. These nine fossil records have most of the criteria established by Martínez-Millán (2010) (see Supplementary Material, Table S2), but their acceptance for calibrating points needs to be carefully evaluated. The first criterion of Martínez-Millán (2010) refers to the inclusion of the fossils in a phylogenetic analysis, but none of the fossil records of Celastraceae have been subject to this type of study since the use of morphological data has been limited in a phylogenetic context (Simmons & Hedin 1999, Simmons et al. 2001a, b).

On the other hand, the second and third criteria refer to the character or character set that supports the identification of the fossil as a member of Celastraceae. This information requires an interpretation within a phylogenetic context (Manchester et al. 2015), because the morphological synapomorphies are considered critical data to establish the relationship between fossil and extant taxa (Parham et al. 2012). Unfortunately, few morphological characters have been identified as synapomorphies in the lineage (e.g., Simmons & Hedin 1999), and most of them are restricted to reproductive structures. For example, Hippocrateoideae is easily recognized by the synapomorphies of transversely, flattened, deeply lobed capsules and seeds with membranous basal wings or narrow stipes, while Salacioideae is identified by berries with mucilaginous pulp (Coughenour et al. 2010, 2011).

Due to the above, the phylogenetic position of the nine fossil taxa is supported through morphological comparison with extant taxa (Figure 2). Morphological similarity recognized in fossil and extant taxa suggests a relationship between them, but this situation may change drastically as more in-depth morphological studies are integrated into a phylogenetic context. Such is the case of Cathispermum pulchrum Reid & Chandler (1933) a five-lobed fruit with winged seeds that have been interpreted as a potential aril. However, presence of an aril is difficult to discern among extant plants and even more difficult in the fossil material. The definition of an aril is complicated to establish (Simmons & Hedin 1999, Simmons 2004, Zhang et al. 2012, 2014). Nevertheless, it typically has been defined for the family as a structure that derives from the funiculus during development (Loesener 1942, Corner 1976). Thus, C. pulchrum, while morphologically like Celastraceae, needs a closer morphological comparison of the aril as discussed in the next paragraph.

According to Simmons (2004), winged seeds have been interpreted as homologues to arilated seeds, as in the case of Catha edulis, which was compared to Cathispermum pulchrum. However, Zhang et al. (2012, 2014) recognized that the tissue surrounding the seed in Catha edulis derives from the micropyle, not from the funiculus. For this reason, it is necessary to consider that the interpretation of C. pulchrum could change as new morphological data or interpretations become available. The biased, incomplete nature of the fossil record is a limitation for its interpretation. In the same way, the lack of detailed morphological studies of extant taxa limits the identification of the fossil record. In Celastraceae, the study of the development of the winged seed is essential to interpret the evolution of this structure (Zhang et al. 2014), as well as the fossil record.

In general, the fossils of reproductive structures are considered reliable records, such is the case of fossil flowers of Celastraceae. All of them are bisexual flowers, with biserial perianth and nectarial disk. Nevertheless, Wuyunanthus has been considered a doubtful record due to its merosity, or the number of parts of the perianth (6 vs. 4-5, Friis et al. 2011). The meristic pattern within the group has modifications that have been little explored (Ronse De Craene 2016).

Identification of fossil flowers could be supported with higher reliability through the recognizing of potential morphological synapomorphies, these include a bulge in the dorsal part of the ovary with an apical septum, and the presence of calcium oxalate druses in floral tissue (Matthews & Endress 2005), but the type of fossilization is a limiting factor for what anatomical characters get preserved. Flowers preserved in amber such as Lobocyclas anomala and Salacia lombardii are exceptional records because they are in three dimensions with relatively little distortion. Access to anatomical characters of plant inclusions in amber has been documented through non-destructive techniques such as microtomography (e.g., Moreau et al. 2016). Further observations on these fossil flowers will help to add support to our suggestion of good calibration point fossils.

Pollen is the most abundant part of the plant fossil record. It is generally identified with relatively low taxonomic resolution (Sauquet et al. 2012). According to Hallé (1960) the characters of pollen have a higher value at the infrageneric level, but these require the integration of information from other organs of the plant for a reliable taxonomic determination.

Tetrads and polyads have been considered as diagnostic characters of Hippocrateoideae, but these are not exclusive to the group. For example, Triporotetradites sp. was related to Campylostemon, but this record has been reexamined and related to other taxa. Such is the case of Triporotetradites letouzeyi from the lower of Miocene of Cameroon (Salard-Cheboldaeff 1978), which is comparable to the pollen of species of Gardenia (Muller 1981). Additionally, unlike in extant plants, it is often difficult to determine in fossil pollen taxa their range of morphological variation (Cleal & Thomas 2010), as in the case of Lophopetalum an extant genus that has both polyads and tetrads (Hou 1969).

Macrofossils are abundant in the fossil record of Celastraceae (Bacon et al. 2016). Specifically, the leaves have been rejected in taxonomic work because they are plastic organs that respond to environmental pressures (Hickey 1973, Hickey & Wolfe 1975). Furthermore, leaf dimorphism is a factor that complicates the taxonomic determination in Celastraceae (Simmons 2004). For instance, Elaeodendron orientale has lanceolate leaves with an entire margin, but when it is a mature plant, its leaves are elliptical with a serrated margin (Simmons 2004). In addition, the lack of a precise description and diagnosis, such is the case of Celastrophyllum, has generated a highly doubtful abundant record in North America and Europe (Doweld 2017, Herendeen 2020). Despite of these limitations, the presence of Celastrus based on fossil leaves can be considered a reliable record based on consistent characters, such as the theoid tooth and camptodromous, craspedodromus or semicraspedodromus venation (Liang et al. 2016).

Woods are recognized as the second organ most abundant in the fossil record of Celastraceae. Their structure and cellular organization under fossilization preserves well providing detailed anatomical data for their identification (Poole 2000). A combination of characters that includes small to medium-sized vessels, apotracheal bands of parenchyma, fine homogeneous rays, and non-septate fibers strongly indicate its affinities with the family Celastraceae (Mehrotra et al. 1983). Moreover, the scalariform perforation plate has been considered diagnostic for the group; however, the phylogenetic context of anatomical data has changed the interpretation of some records. For example, Perrottetioxylon mahurzari (Chitaley & Patel 1971) and Gondwanoxylon (Saksena 1962) were closely compared to Perrottetia, a genus traditionally considered an atypical member of Celastraceae. Its inclusion within Celastraceae was supported by anatomical characters, such as the presence of scalariform perforation plate, paratracheal parenchyma and absence of fiber tracheids (Metcalfe & Chalk 1983, Simmons & Hedin 1999). However, Zhang & Simmons (2006) determined the exclusion of Perrottetia from this family through a phylogenetic analysis using molecular characters.

Although the fossil record of Celastraceae is scarce as point calibration according to criteria proposed by Martínez-Millán (2010), their geographic distribution suggest the dispersion between North America, Europe and Asia during the early Paleogene to the Pliocene (Wolfe 1975, Tiffney & Manchester 2001, Graham 2018). This hypothesis is supported by Magallón et al. (2019) that suggested that the diversification of the lineage was as a relevant event for angiosperms during the Paleogene ca. (68.40) 51.1 (42.83) Ma.

The selection of reliable fossils as calibration points is critical for reconstructing robust phylogenies. Unfortunately, the inherent fragmentary nature of fossil plants limits access to molecular characters and other sources of information, with morphology and anatomy being the most frequent source of information available for study (Wiens 2004). Consequently, an in-depth study of the morphological characters in a phylogenetic context in Celastraceae is essential (e.g., Simmons & Hedin 1999), since only through this will it be possible to generate a better interpretation and evaluation of their fossil record. It is also necessary to increase the value of fossils through the reconstruction of complete plants, as this work will significantly complement the understanding of plants in terms of variability and distribution of characters over time. After detailed evaluation and discussion, we propose nine fossil reports of Celastraceae as reliable and well supported to be used as calibration points. However, further studies need to be conducted towards phylogeny of the family.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here: https://doi.org/10.17129/botsci.2802

nova página do texto(beta)

nova página do texto(beta)