Traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) is a cumulative body of knowledge, practices and beliefs about the relationship of living beings with their environment, which evolve through adaptive processes and is culturally communicated across generations (Berkes 1993). TEK is crucial for carrying out local actions for conservation, ecological restoration and recovering biological populations, particularly those of useful species (Levy-Tacher et al. 2012, Casas et al. 2014, 2016, Chekole 2017). TEK provides decision makers with valuable information about distribution, abundance, biotic interactions, behavior, recovering capacity of organisms and ecosystems following disturbance, among other issues. In addition, TEK has proved its usefulness in identifying valuable ecosystems and resources to be protected and recovered, as well as management experiences to shorten the ways for attaining sustainable management strategies (Casas et al. 2014, 2016). Some ecological restoration efforts have started from documenting the most valuable resources, among them edible, fuel, and timber producing plants (Vázquez-Yanes et al. 1999, Lindig-Cisneros 2017). Yet few studies have been conducted considering medicinal plants (Charnley et al. 2008, Suárez et al. 2012, Velázquez-Rosas et al. 2018), notwithstanding that this group of plants commonly is the largest in ethnobotanical inventories (Toledo et al. 1995).

Traditional medicinal knowledge (TMK) is a crucial component of TEK. Both TMK and TEK study botanical, zoological, ecological, and technological knowledge combining empirical, rational, logical knowledge and symbolic, mythological and magical thinking that distinguishes the human being as a social and cultural being (Fagetti 2011). TMK focuses on elements associated to treat illnesses (Fagetti 2011), while TEK analyses more general aspects of biological species and their environment and ecosystems (Berkes 1993, Casas et al. 2016). TMK and TEK are locally generated and transmitted from generation to generation through oral, practical or written means (Foster 1953, Pochettino & Lema 2008); however, TMK has played a crucial role in survival and has helped humanity to face threats to its physical, emotional and spiritual integrity; it is widely used for attending health problems, both for preventing and treating illnesses of many populations (WHO 2013). The use of TMK occurs predominantly in poor rural areas, commonly involving traditional physicians recognized within and among communities (Cabrera et al. 2015). Traditional medicine is practiced in almost all countries of the world (WHO 2013), covering nearly 80 % of the global needs of health (Akerele 1993, Fabricant & Farnsworth 2001, WHO 2002). Its use is key for people with poor access to official health services, and it is the main way of providing health help for indigenous communities (Hamilton 2004, Quinlan & Quinlan 2007, WHO 2013).

Despite the relevance of TEK and TMK, their loss is occurring worldwide (Anyinam 1995, Cox 2000, Lulekal et al. 2008, Brito et al. 2017). Among the multiple and complex factors influencing such process, authors like Linares & Bye (1987), Toledo (1987), Berkes & Turner (2005) have identified: (1) decreasing interest of young people to learn and transmit traditional knowledge (Phillips & Gentry 1993, Luoga et al. 2000, Voeks & Leony 2004, Reyes-García et al. 2013); (2) loss of the original languages in which that knowledge is transmitted (Benz et al. 2000, Maffi 2005); (3) modernization (Quinlan & Quinlan 2007) and new economic contexts (Reyes-García et al. 2005) favoring disarticulation of communities, migration, loss of culture and use of local medicinal flora (Vandebroek & Balick 2012, Alencar et al. 2014), and their replacement by modern patented medicines (Luziatelli et al. 2010, Reyes-García et al. 2013). The increasing loss of traditional knowledge may be expected to have consequences on the resilience of socio-ecological systems (Brito et al. 2017) since it tends to weaken the resources and ecosystems value and the need and relevance to maintain them (Toledo et al.1992, Voeks 1996, Weldegerima 2009, Silalahi et al. 2015, Brito et al. 2017).

Most of biodiversity on Earth occurs in tropical regions, particularly in those areas identified as “hotspots”, which however are rapidly decreasing (Ryan 1992, Begossi et al. 2000, Myers et al. 2000). It has been recognized that in these areas live most of the indigenous peoples (Mace & Pagel 1995, Moore et al. 2002, Maffi 2005), and that they are the main custodians and stewards of ecosystems and biological diversity of “hotspots”. In Mexico, tropical ecosystems are important reservoirs of the country’s biodiversity, harboring nearly 17 % of its flora (Rzedowski 1998, Challenger & Soberón 2008). However, extensive land-use change through deforestation aimed to establish pastures for livestock raising, traditional agriculture, and establishing plantations of commercial crops has reduced the extent and increased the isolation of the remaining fragments of original forest habitats (Challenger 1998, Koleff et al. 2012).

It has been estimated that only one-half of the original cover of tropical rain forest of Mexico remains relatively well preserved (Masera et al. 1992, Challenger & Soberón 2008, Koleff et al. 2012). In the state of Tabasco, where this study was conducted, the estimated original cover of tropical rain forest was 21.7 % of the State´s area, only 1.6 % of which remained at the beginning of this century (Sánchez-Munguía 2005). Ecological restoration implies the process of recovering ecosystems degraded, damaged or destroyed by natural and anthropogenic causes (SER 2004); it is based on a historical past with the aim of achieving short-term community benefits along with long-term social commitments to promote locally the ecological integrity, sustainability and long-term resilience of communities and ecosystems in the face of climate change (Suding 2011, DeFries et al. 2012, Suding et al. 2015). Programs aimed to forest cover restoration are urgent that may consider merging extant TEK and TMK in order to facilitate their local social construction, long-term adoption and foster wider use of biodiversity (González-Espinosa et al. 2008, Ramírez-Marcial et al. 2014, García-Barrios & González-Espinosa 2017).

The purpose of this study was to identify tree species that are used medicinally through traditional medicinal knowledge (TMK) which could be included in restoration practices aimed to increase forest cover. The study was conducted in four Zoque-Maya communities in the southern mountainous region of the state of Tabasco, in southeastern Mexico. We followed an ethnobotanical approach in documenting the use of native medicinal trees, the most important illnesses attended with them, and their cultural value for local people as important species in restoration actions. We also obtained the indexes of cultural significance of the species and knowledge wealth, and we identified the role of gender to discriminate whether it is men or women who possess this wealth of knowledge. Our study aims to illustrate the relevance of TMK for selecting tree species and designing strategies of ecological restoration of tropical forests.

Materials and methods

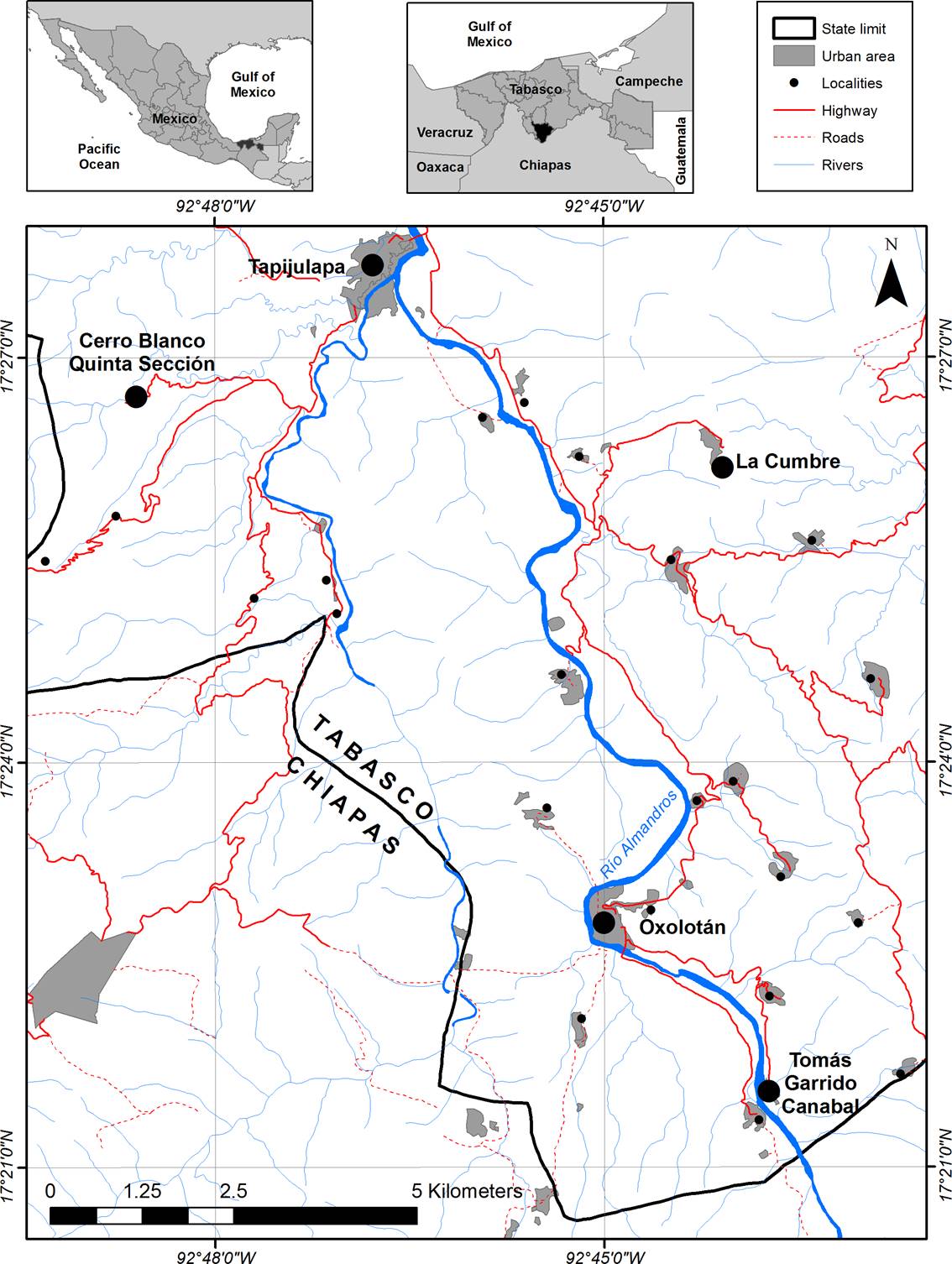

Study area. The study was conducted in the municipality of Tacotalpa (between 17° 20’ and 17° 42’ North; 92° 32’ and 92° 55’ West; elevation 20-1,000 m) in the Sierra region of the state of Tabasco (INEGI 2005), and in the eco-geographic unit of the abrupt northern slopes of the Sierra Norte of Chiapas (Ortiz-Pérez et al. 2005) in southeastern Mexico. The regional climate is warm-humid, with rains throughout the year, with annual rainfall of 1,500-4,500 mm (INEGI 2015). The area belongs to the Grijalva-Usumacinta hydrological region and the Grijalva-Villahermosa river basin, in which the Puxcatán, Almandros, Amatán, Chinal, and Tacotalpa rivers converge (INEGI 2005). The geology is characterized by Tertiary sedimentary rocks (shale-sandstones and limestones); dominant soils include shallow and rocky lithosols in the slopes and gleysols in lower areas, whose texture is generally clay, silt or silty clay, with problems of excess moisture due to poor drainage in low areas (INEGI 2005, Bensusán 2011).

Vegetation mostly includes secondary plant associations and small relicts of tropical rain forest (Miranda & Hernández-X 2014, Rzedowski 2006), mostly with a high degree of human disturbance (Ramírez-Marcial et al. 2014). In the less accessible areas, an average density of 32 stems per hectare belonging to at least four tree species has been reported for the pasture-dominated landscape (Grande-Cano et al. 2009). Salazar-Conde et al. (2004) report loss of tropical rain forest cover (with Brosimum alicastrum as dominant species) reaching up to 80 % within the last quarter of the past century.

We worked in four communities: Oxolotán (OX, 1,886 inhabitants, 10.4 % speak indigenous language); Cerro Blanco Quinta Sección (CB, 565 inhabitants, 7.1 % speak indigenous language); Tomás Garrido Canabal (TG, 389 inhabitants, 8.5 % speak indigenous language), and La Cumbre (LC, 238 inhabitants, 19.1 % speak indigenous language) (INEGI 2010). People of these communities belong to the Mayan ethnic groups Ch’ol, Chontal, and Tzotzil, yet a significant proportion belong to the Zoque and Mestizo groups. The degree of poverty is high in almost all communities except Oxolotán, where it has been estimated at an intermediate level (INEGI 2010) (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Study area and location of studied communities in the Sierra region of southern Tabasco, Mexico.

Ethnobotanical studies. We obtained a preliminary checklist of medicinal trees occurring in the area through a literature review of floristic and ethnofloristic sources (Maldonado-Mares 2005, Magaña-Alejandro 2006, López-Hernández 1994, Ramírez-Marcial et al. 2014), which was used as a reference for other steps of the research. In addition, we identified whether or not those species receive any management, particularly if there were previous experiences of using them in restoration programs in the area or somewhere else.

Fieldwork started by asking permission from local authorities, as well as informing people and asking their consent for participating in the interviews. We then carried out semi-structured interviews (Albuquerque et al. 2014, Brito et al. 2017), during September and October 2015, to men and women of the four communities. We used the qualitative method called “snow ball” (Bernard 1995) for sampling interviewees recognized as experts in relation to the medicinal flora of the region.

In the OX community we conducted 28 interviews, 29 in CB, 26 in TG, and 24 in LC (See Appendix 1). We recorded name, gender and age of people interviewed, and questions were addressed to explore their ability to recognize medicinal flora using printed photographs of the species included in the reference checklist referred to above. In addition, we explored people’s identification of medicinal uses, illnesses treated with them, their form of administration, and their opinion on whether the tree species should be used in forest restoration activities in the region. This opinion was generally based on the low availability of the resource and the difficulty of natural regeneration of certain species. By means of the free listing technique we analyzed the most valuable species among medicinal trees.

We carried out a workshop in each community in October 2015 with the participation of the people interviewed: 18 people in CB, 16 in OX, 13 in LC, and 11 in TG. The workshops aimed at collectively selecting those medicinal tree species that could be considered with a high priority for forest restoration. We asked the people to name the 10 species of trees considered the most recommended to carry out actions of forest restoration (including their propagation and reintroduction to floristically enrich fallow stands); participants indicated the highest priority by number 1 and successively down until 10. We also asked them to comment about their criteria for their selection, which was commonly based on the low availability of the resource.

Data processing and analysis. We categorized the individually interviewed women and men from each community in different age groups. In addition, we categorized the most common illnesses and related affections, according to the information of the interviewees. We determined the most important illnesses in each community, the number of species used for treating the same illness, and the number of illnesses treated by each species. In each community we obtained the percentage of interviewees who considered each of the tree species with priority in restoration actions; we also obtained the percentage of the communities in which it was considered with some value of importance to a species.

We analyzed the amount of knowledge on use of medicinal trees through the Index of Knowledge Richness (IKR), following Toscano (2006), Castellanos-Camacho (2011)), and Medellín-Morales et al. (2017). We identified whether men or women possess this wealth of knowledge. For calculating this index we used the reference checklist and the free listing of medicinal trees reported by people interviewed in each community, using the formula:

In which, IKR is the proportion of species of medicinal trees reported by each interviewee in relation to the number of medicinal tree species reported by all people interviewed in the whole region; [SU]i is the number of species of medicinal trees recorded by the interviewee with respect to [SU]total, the total number of species of medicinal trees reported in the whole region by all the interviewees. Values of this index may vary from 0 to 1, being 1 the maximum value of richness value of the medicinal trees of the region.

For determining the species that are culturally most significant because of their use as medicines, we calculated the Index of Cultural Significance (ICS), based on parameters of quality (perceived effectiveness as medicines), intensity (use frequency), and exclusiveness (the plant as main or a non-substitutable component of a remedy) of the use of each species, based on Turner (1988) and Stoffle et al. (1990). For this study, we considered only the different medicinal uses reported by people. We adapted the ICS for this study as follows:

The expanded formula being:

The formula indicates the sum of 1 to n medicinal uses (u) for a species, where q = medicinal uses (use values from 5 to 0.5, according to categories of illnesses mentioned by the interviewees); I = intensity of use (values from 5 to 1, where 5 = very intense, 4 = intense, 3 = intermediate intense, 2 = low, 1 = very low); e = exclusivity of use (values from 2 to 0.5, where 2 = high, 1 = intermediate, and 0.5 = low); Ninf = total number of informants of people interviewed.

We finally analyzed the Cumulative Importance of Cultural Significance (CICS) of each species recorded in each community following the index of cultural importance by Stoffle et al. (1990). The CICS makes reference to the sum of ICS of each species of medicinal trees recorded in each community.

Results

Traditional medicinal knowledge of tropical tree species. The reference checklist included 21 species of medicinal trees, belonging to 21 genera and 14 plant families. Based on the free listing technique, we recorded 22 species and 2 morphospecies, belonging to 22 genera and 16 plant families. From the reference checklist and the free listing, in the OX community we summed a total of 34 species, belonging to 30 genera and 16 plant families; values for the other communities were: 31 species, belonging to 29 genera and 19 plant families in TG; 30 species belonging to 28 genera and 15 plant families in LC, and 28 species belonging to 26 genera and 15 plant families in CB. A total of 45 tree species with at least one medicinal use were recorded in the four studied communities (Table 1).

Table 1 Tropical medicinal tree species included in the reference list (*) and the free list (**) in the four study communities in southern Tabasco, Mexico.

| Community | |||||

| Family | Species | Oxolotán | Cerro Blanco | Tomás Garrido | La Cumbre |

| Anacardiaceae | Spondias mombin L.** | x | |||

| Spondias purpurea L.** | x | x | |||

| Annonaceae | Annona reticulata L.* | x | x | x | x |

| Annona muricata L.** | x | x | x | x | |

| Bignoniaceae | Handroanthus guayacan (Seem.) S.O.Grose** | x | x | ||

| Parmentiera aculeata (Kunth) L.O.Williams** | x | x | |||

| Tabebuia rosea DC.* | x | x | x | x | |

| Bixaceae | Bixa orellana L.** | x | x | ||

| Burseraceae | Bursera graveolens Triana & Planch.** | x | |||

| Bursera simaruba (L.) Sarg.* | x | x | x | x | |

| Caricaceae | Carica mexicana (A.DC.) L.O.Williams** | x | |||

| Clusiaceae | Mammea americana L.** | x | |||

| Cochlospermaceae | Cochlospermum vitifolium Spreng.** | x | |||

| Euphorbiaceae | Croton draco Schltdl.** | x | x | ||

| Lamiaceae | Cornutia pyramidata L.** | x | |||

| Lauraceae | Persea americana Mill.* | x | x | x | x |

| Leguminosae | Acacia cornigera (L.) Willd.** | x | |||

| Cassia grandis L.** | x | x | x | ||

| Erythrina americana Mill.* | x | x | x | x | |

| Gliricidia sepium (Jacq.) Kunth* | x | x | x | x | |

| Haematoxylum campechianum L.** | x | ||||

| Inga jinicuil Schltdl.** | x | ||||

| Inga punctata Willd.** | x | ||||

| Senna sp.** | x | ||||

| Malpighiaceae | Byrsonima crassifolia Kunth* | x | x | x | x |

| Malvaceae | Ceiba pentandra (L.) Gaertn* | x | x | x | x |

| Guazuma ulmifolia Lam.* | x | x | x | x | |

| Pachira aquatica Aubl.* | x | x | x | x | |

| Pseudobombax ellipticum (Kunth) Dugand* | x | x | x | x | |

| Theobroma cacao L.* | x | x | x | x | |

| Meliaceae | Cedrela odorata L.* | x | x | x | x |

| Trichilia havanensis Jacq. ** | x | x | x | ||

| Moraceae | Brosimum alicastrum Sw.* | x | x | x | x |

| Castilla elastica Sessé in Cerv.* | x | x | x | x | |

| Ficus glaucescens Miq.** | x | ||||

| Myrtaceae | Pimenta dioica (L.) Merr.* | x | x | x | x |

| Psidium guajava L.** | x | x | x | x | |

| Piperaceae | Piper auritum Kunth * | x | x | x | x |

| Rubiaceae | Blepharidium mexicanum Standl.** | x | |||

| Genipa americana L.* | x | x | x | x | |

| Sickingia salvadorensis Standl.** | x | ||||

| Sapotaceae | Manilkara zapota (L.) P. Royen* | x | x | x | x |

| Pouteria sapota (Jacq.) H. E. Moore & Stearn* | x | x | x | x | |

| Pouteria sp.** | x | ||||

| Urticaceae | Cecropia obtusifolia Bertol.* | x | x | x | x |

We recorded 14 categories of recurrent illnesses that are treated with medicinal tree species within the study region (Table 2). The most common illnesses registered were gastrointestinal (93-97 %) which are attended with 13 species, and those associated to pain and fever (67-97 %), which are attended with 16 species (Tables 3 and 4). The species that were reported for treating the highest number of illnesses were Persea americana and Cecropia obtusifolia (8 categories of illnesses); Genipa americana was not reported to be used as medicine in the communities studied, although it is reported in other communities of the state of Tabasco (Table 4).

Table 2 Categories of recurrent illnesses treated with medicinal tree species in the region and their description.

| No. | Category of illness | Use values | Illnesses and symptoms in the category |

| 1 | Gastrointestinal | 5 | vomiting, parasites, constipation, diarrhea, gastritis, colitis, stomach pain-infection, dysintery |

| 2 | Respiratory | 5 | cold, cough, flu, asthma, hoarseness |

| 3 | Dermatolological | 5 | wounds, ulcers, sores, burns, blows, fungus, dandruff (hair not cane), pimples |

| 4 | Pain and/or fever | 4 | fever, muscle pain, bone pain, headache, earache, toothache, nosebleeds |

| 5 | Women´s health issues | 4 | cramps, menstrual problems, infections, childbirth related issues |

| 6 | Urological | 4 | urinary infections, kidney pain, prostate problems |

| 7 | Ocular | 3 | infections, cataracts, conjunctivitis, red teary eyes |

| 8 | Cancer | 3 | |

| 9 | Diabetes | 3 | blood sugar and glucose imbalances |

| 10 | Smallpox, chicken pox, measles | 2 | |

| 11 | Blood related problems | 2 | anemia, leukemia, high cholesterol, high triglyceride levels, varicose veins, high or low blood pressure |

| 12 | Insect and animal bites | 1 | |

| 13 | Ceremonies and spirit/sould related problems | 1 | ritual use, fright, protection, air, evil eye, smudging, crying in children, weakness |

| 14 | Others | 0.5 | nerves, insomnia, convulsions |

Table 3 Percentage of recurrent illnesses treated with medicinal tree species in the four study communities. Number of interviews in each community are in parentheses.

| Communities | |||||||

| Oxolotán (28) | Cerro Blanco (29) | Tomás Garrido (26) | La Cumbre (24) | ||||

| Category of Illness | % | Category of Illness | % | Category of Illness | % | Category of Illness | % |

| Gastrointestinal | 93 | Gastrointestinal | 97 | Pain and/or fever | 92 | Gastrointestinal | 96 |

| Pain and/or fever | 89 | Pain and/or fever | 97 | Smallpox, chicken pox, measles | 77 | Pain and/or fever | 67 |

| Dermatolological | 75 | Dermatolological | 62 | Gastrointestinal | 73 | Ceremonies and spirit/sould related problems | 50 |

| Diabetes | 43 | Ceremonies and spirit/sould related problems | 62 | Dermatolological | 58 | Smallpox, chicken pox, measles | 38 |

| Smallpox, chicken pox, measles | 39 | Smallpox, chicken pox, measles | 59 | Ceremonies and spirit/sould related problems | 46 | Women´s health issues | 33 |

| Blood related problems | 36 | Women´s health issues | 31 | Blood related problems | 42 | Diabetes | 33 |

| Respiratory | 29 | Diabetes | 31 | Urological | 38 | Dermatolological | 29 |

| Ceremonies and spirit/sould related problems | 25 | Ocular | 28 | Women´s health issues | 35 | Blood related problems | 21 |

| Ocular | 25 | Urological | 17 | Diabetes | 27 | Respiratory | 17 |

| Women´s health issues | 21 | Respiratory | 14 | Ocular | 12 | Ocular | 4 |

| Urological | 14 | Blood related problems | 10 | Insect and animal bites | 4 | Insect and animal bites | 4 |

| Cancer | 0 | Others | 7 | Others | 4 | Others | 4 |

| Insect and animal bites | 0 | Insect and animal bites | 3 | Respiratory | 0 | Urological | 0 |

| Others | 0 | Cancer | 3 | Cancer | 0 | Cancer | 0 |

Table 4 Recurrent illnesses in the region and medicinal tree species that treat these illnesses in the four study communities of Tabasco, Mexico.

| Category of illness | |||||||||||||||

| Medicinal tree species | Respiratory | Gastrointestinal | Dermatological | Pain and/or fever | Women´s health issues | Urological | Ocular | Cancer | Diabetes | Smallpox, chicken pox, measles | Blood related problems | Insect and animal bites | Ceremonies and spirit/sould related problems | Others | Total number of illnesses treated with the species |

| Persea americana | X | X | x | x | x | x | x | x | 8 | ||||||

| Cecropia obtusifolia | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | 8 | ||||||

| Annona reticulata | X | x | x | x | x | x | x | 7 | |||||||

| Tabebuia rosea | X | X | x | x | x | x | x | 7 | |||||||

| Gliricidia sepium | X | x | x | x | x | x | 6 | ||||||||

| Guazuma ulmifolia | X | X | x | x | x | x | 6 | ||||||||

| Cedrela odorata | X | X | x | x | x | x | 6 | ||||||||

| Piper auritum | X | X | x | x | x | x | 6 | ||||||||

| Manilkara zapota | X | x | x | x | x | x | 6 | ||||||||

| Pouteria sapota | X | x | x | x | x | x | 6 | ||||||||

| Bursera simaruba | X | x | x | x | x | 5 | |||||||||

| Theobroma cacao | X | x | x | x | x | 5 | |||||||||

| Pimenta dioica | X | X | x | x | x | 5 | |||||||||

| Erythrina americana | x | x | x | x | 4 | ||||||||||

| Byrsonima crassifolia | X | x | x | x | 4 | ||||||||||

| Pachira aquatica | x | x | x | x | 4 | ||||||||||

| Castilla elastica | X | x | x | 3 | |||||||||||

| Ceiba pentandra | x | x | 2 | ||||||||||||

| Brosimum alicastrum | x | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Genipa americana | 0 | ||||||||||||||

| Pseudobombax ellipticum | 0 | ||||||||||||||

| Total number of species that treat the category of illness | 7 | 13 | 11 | 16 | 10 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 11 | 2 | 9 | 3 | |

Knowledge Richness and Cultural Significance of the Species studied. Most interviews were carried out to women since the snow ball technique conducted to them, because of their expertise in using medicinal plants. Ages of women were 29 to 100, whereas men were 34 to 87 years old (Appendix 1).

The community of OX had the highest value of IKR (0.62), representing 62 % of the species reported (21 of 34 species reported in the community). In OX the highest IKR was registered among elder women from 71 to 80 years old. In TG the highest IKR (0.58) was registered among women from 61 to 70 years old, whereas in CB it was 0.57 among younger women, 41-50 years old; in LC the IKR was 0.53 among women 41-70 years old. Values of IKR in all communities averaged 10 to 11 species of medicinal trees (Table 5, Appendix 1).

Table 5 Index of Knowledge Richness (IKR) of the four study communities. The total number of medicinal tree species (MTS) is the sum resulting from the floristic reference list and the free list; S = number of species.

| Community | Total no. interviews | Total no. MTS | Max. IKR | Smax | Min. IKR | Smin | Mean IKR | Smean |

| Oxolotán | 28 | 34 | 0.62 | 21 | 0.06 | 2 | 0.33 | 11 |

| Cerro Blanco | 29 | 28 | 0.57 | 16 | 0.11 | 3 | 0.36 | 10 |

| Tomás Garrido | 26 | 31 | 0.58 | 18 | 0.19 | 6 | 0.35 | 11 |

| La Cumbre | 24 | 30 | 0.53 | 16 | 0.13 | 4 | 0.32 | 10 |

The species with the highest cultural importance, according to the cumulative cultural significance was Gliricidia sepium, which had the highest values of ICS in the communities OX, CB, and TG. Bursera simaruba, Piper auritum, Pimenta dioica, Theobroma cacao, Guazuma ulmifolia, and Byrsonima crassifolia were classified in the category of high cultural importance (Table 6).

Table 6 Index of cultural significance (ICS) and cumulative index of cultural significance (CICS) of medicinal tree species in the four study communities in southern Tabasco, Mexico. Levels of cultural significance are based on Turner (1988): very high ≥ 100; high = 50-99; moderate = 20-49; low = 5-19; very low = 1-4; unimportant = 0.

| ICS/ community | ||||||

| Species | Oxolotán | Cerro Blanco | Tomás Garrido | La Cumbre | CICS | Cumulative level of cultural significance |

| Gliricidia sepium | 33 | 46 | 36 | 20 | 135 | very high |

| Bursera simaruba | 13 | 40 | 11 | 25 | 89 | high |

| Piper auritum | 35 | 31 | 18 | 4 | 87 | high |

| Pimenta dioica | 26 | 7 | 21 | 22 | 75 | high |

| Theobroma cacao | 18 | 20 | 16 | 11 | 65 | high |

| Guazuma ulmifolia | 9 | 15 | 17 | 19 | 60 | high |

| Byrsonima crassifolia | 14 | 19 | 6 | 11 | 50 | high |

| Persea americana | 14 | 7 | 10 | 13 | 45 | moderate |

| Cedrela odorata | 17 | 5 | 17 | 3 | 42 | moderate |

| Pouteria sapota | 15 | 13 | 9 | 4 | 41 | moderate |

| Tabebuia rosea | 11 | 11 | 9 | 7 | 37 | moderate |

| Annona reticulata | 12 | 0 | 9 | 8 | 29 | moderate |

| Cecropia obtusifolia | 8 | 2 | 6 | 14 | 29 | moderate |

| Manilkara zapota | 6 | 3 | 9 | 3 | 20 | moderate |

| Castilla elastica | 3 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 16 | low |

| Erythrina americana | 0 | 0 | 8 | 2 | 10 | low |

| Pachira aquatica | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 9 | low |

| Ceiba pentandra | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | very low |

| Brosimum alicastrum | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | very low |

| Genipa americana | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | unimportant |

| Pseudobombax ellipticum | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | unimportant |

Priority species for ecological restoration. Information resulting from workshops indicated that 15 tree species are of high interest for actions of forest restoration. This selection is mainly due to the local criterion of low availability of a resource and the difficulty of reproduction since some species are "rogadas", as people say, which means that they do not seem to reproduce easily in the wild. These species were also considered as important by 61-100 % of the people interviewed in each community (Table 7). Such is the case of Manilkara zapota which was considered by all people interviewed in OX and TG as a species that should be considered in restoration actions; the same was recorded for Brosimum alicastrum in TG (Table 7). Annona reticulata, Tabebuia rosea, Persea americana and Brosimum alicastrum received an importance value in the workshops, providing support to their use as priority species in ecological restoration actions in the four communities (100 %). On the other hand, because of their widespread occurrence in the region, Bursera simaruba, Cecropia obtusifolia, Gliricidia sepium, Erythrina americana and Piper auritum did not receive importance values in any community (0 %). Pseudobombax ellipticum is a species was not known to occur in the forest areas by any participant in the workshops and interviews (Table 7).

Table 7 Priority species in the study communities for use in ecological restoration. W = Workshops, VI = Value of importance, range from 1 to 10, where 1 is the species of greatest priority for restoration projects; I = Interviews, Percentage of interviewed who consider the priority species for restoration.

| Priority species for restoration in each community | ||||||||||

| Oxolotán | Cerro Blanco | Tomás Garrido | La Cumbre | % Species

priority. Community workshops |

||||||

| No. | Species | W (VI) | I (%) | W (VI) | I (%) | W (VI) | I (%) | W (VI) | I (%) | |

| 1 | Annona reticulata | 8 | 82 | 2 | 90 | 3 | 96 | 1 | 83 | 100 |

| 2 | Tabebuia rosea | 7 | 68 | 1 | 79 | 8 | 88 | 8 | 79 | 100 |

| 3 | Persea americana | 9 | 61 | 5 | 69 | 5 | 81 | 10 | 67 | 100 |

| 4 | Brosimum alicastrum | 5 | 82 | 8 | 72 | 2 | 100 | 5 | 71 | 100 |

| 5 | Pimenta dioica | 6 | 89 | 3 | 97 | 81 | 4 | 83 | 75 | |

| 6 | Genipa americana | 3 | 68 | 9 | 62 | 9 | 73 | 58 | 75 | |

| 7 | Manilkara zapota | 4 | 100 | 4 | 97 | 4 | 100 | 79 | 75 | |

| 8 | Pouteria sapota | 89 | 6 | 86 | 1 | 96 | 6 | 79 | 75 | |

| 9 | Pachira aquatica | 54 | 7 | 62 | 58 | 2 | 75 | 50 | ||

| 10 | Byrsonima crassifolia | 10 | 64 | 31 | 7 | 62 | 33 | 50 | ||

| 11 | Theobroma cacao | 2 | 75 | 41 | 6 | 96 | 88 | 50 | ||

| 12 | Cedrela odorata | 1 | 89 | 66 | 77 | 3 | 79 | 50 | ||

| 13 | Ceiba pentandra | 54 | 59 | 10 | 65 | 7 | 67 | 50 | ||

| 14 | Castilla elastica | 64 | 10 | 62 | 50 | 58 | 25 | |||

| 15 | Guazuma ulmifolia | 36 | 21 | 38 | 9 | 63 | 25 | |||

| 16 | Bursera simaruba | 32 | 17 | 23 | 29 | 0 | ||||

| 17 | Cecropia obtusifolia | 14 | 3 | 0 | 17 | 0 | ||||

| 18 | Gliricidia sepium | 25 | 28 | 27 | 33 | 0 | ||||

| 19 | Erythrina americana | 36 | 38 | 38 | 29 | 0 | ||||

| 20 | Piper auritum | 4 | 14 | 15 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 21 | Pseudobombax ellipticum | 7 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | ||||

Discussion

Cultural significance of tree species and its value for ecological restoration. In total, we identified 45 species of trees with medicinal use in the region. This group of species includes elements of both primary and secondary vegetation. Such number of tree species represents 5.5 % of the species reported by Toledo et al. (1995) in his study of useful plant species from the tropical rainforest of Mexico. The main categories of illnesses in the study area are gastrointestinal, as well as those causing pain and fever, similarly as reported in other studies among indigenous peoples (Sepúlveda 1993, Magaña-Alejandro et al. 2010, Gómez-Álvarez 2012). In this study, we found different species used for treating different illnesses, which we interpret as conferring resilience to the local capacities for attending health. However, we also identified tree species that may be used for treating different illnesses (up to eight), which is an indicator of the use value of particularly important species; yet it is also an indicator of vulnerability of the traditional health systems since if populations of these species are affected by disturbance, the local capacities for attending health might be affected. Traditional knowledge associated with the use of a particularly declining species also runs that same risk of disappearing at local or regional scales (Albuquerque et al. 2006, Shaheen et al. 2017); in our study, an example of this coupling between ecology and knowledge seems to be the case of Pseudobombax ellipticum, which is not reported any longer to be extant in the region and therefore no associated uses of it were detected.

The analysis of the cultural significance of species (as an integral representation of the multiplicity of uses of a plant species) is a quantitative ethnobotanical evaluation for understanding the most meaningful resources in a human cultural context (Turner 1988, Stoffle et al. 1990, Bennett & Prance 2000, Almeida et al. 2005, Albuquerque & Lucena 2005, Silva & Albuquerque 2005, Silva et al. 2006, Helida et al. 2015), and may be particularly helpful for designing strategies of protection and conservation of biological diversity (Turner 1988, Gupta 2004, Reyes-García et al. 2006, Hoffman & Gallaher 2007). Our study emphasizes ecological restoration, since our efforts are aimed at identifying species of local interest that can be used to recover deforested or degraded forest areas.

A number of studies have been reported where species with high cultural importance may be severely impacted by local exploitation (e.g.Albuquerque & Lucena 2005, Albuquerque 2006). According to Turner (1988), the higher the number of uses of a plant species, the higher the probability of having a higher cultural value for a community. This value may vary for a species in different contexts of knowledge, use, human culture, and environmental conditions (Turner 1988, Pei et al. 2009). Although most valuable resources may probably be most affected, these may also be those on which peoples have developed management experiences (Casas et al. 1997, 2007, 2016, 2017). It has been documented in different parts of Mexico that plant species highly valued by people but with a restricted distribution and scarce availability, as well as other indicators of vulnerability to extraction (long life cycle, specialized breeding system, low capacity of recovering to disturbance, among other features), are those on which people develop more careful and complex management techniques (Arellanes et al. 2013, Blancas et al. 2010, 2013, Rangel-Landa et al. 2017). Managed or not, these species may be in risk to disappear if high use intensity prevails on them; yet if there are management techniques available the restoration programs would be benefited.

In this study, Persea americana and Cecropia obtusifolia are not the most culturally valued species, yet they are widely used for attending the highest number of illnesses; moderate values of cultural significance of these species are due to the low frequency and exclusiveness of their uses. Gliricidia sepium, Bursera simaruba and Piper auritum, have high and very high cultural importance. This would suggest using these species in actions of ecological restoration. However, the quantitative ethnobotanical analysis does not reflect the real interest that people have in using these species in ecological restoration projects. In the case of Gliricidia sepium and Piper auritum, because of their growth habit and habitat restricted to highly lighted spots, it would not be expected to contribute to creating a forest cover. In addition, none of these two species are valued as a source of fuelwood or other timber uses. Finally, this appreciation is also explained because some of these species are locally abundant and, as people say “they grow by themselves”, which makes reference to the fact that these species reproduce and grow easily and their products are also easily obtained. Similar cases are also the species Cecropia obtusifolia and Erythrina americana.

Particular attention deserves the case of Brosimun alicastrum, a species of very low cultural significance but yet considered a priority species for ecological restoration. This latter consideration is based on the recognition of its low availability, which makes necessary to walk long distances to reach its useful products. Similar are the cases of Manilkara zapota and Cedrela odorata, the latter a species registered in the official Mexican norms for protection NOM 059, due to its scarcity (SEMARNAT 2010) and progressive population depletion (Hernández-Ramos et al. 2018). From these cases, a few lessons can be extracted. First, ethnobotanical and cultural value considerations for protection and restoration should not be restricted to a single use criterion but they should consider their broad spectrum of uses and benefits. Second, the local perception of distribution, abundance and vulnerability of the populations should be considered. Third, the local experiences about managing plant species are crucial because they reflect the local worries of people to maintain those plants, and they may also provide particular techniques to planning successful actions.

Species of medicinal trees recorded in this study and with high priority for their use in forest restoration practices are part of the primary vegetation (Brosimun alicastrum and Manilkara zapota), while Pouteria sapota, Genipa americana and Pimenta dioica are part of both primary and secondary forests. Castilla elastica, Cedrela odorata, and Guazuma ulmifolia are pioneer species in secondary vegetation, as well as Ceiba pentandra, Tabebuia rosea, Anonna reticulata, Persea americana, Theobroma cacao and Byrsonima crassifolia (Pennington & Sarukhán 2005, Parker 2008, González-Espinosa & Ramírez-Marcial 2013). Most tree species selected for medicinal use in the study area are part of the secondary vegetation, which is not surprising since as Toledo et al. (1995) and other authors have reported, secondary forests are the main providers of medicinal products, nearly twice than primary forests. Stepp (2004) and Voeks (2004) mention that anthropic landscapes are the main source of medicines in tropical forests. In addition, numerous authors (Toledo et al. 1992, Voeks 1996, Chazdon & Coe 1999, among others) identify disturbed areas as sites where medicinal plants are particularly abundant.

The study area has been drastically impacted by humans for many centuries. Several important cultures inhabited and managed the regional forests for thousands of years. Yet the most drastic destruction started in the mid-20th century, with governmental programs aimed to transform tropical rain forests into pastures and monocultures over extensive areas (Tudela 1989, Sánchez-Munguía 2005); this process has advanced until the present with strong consequences on losing of biodiversity and traditional cultures (Gómez-Pompa et al. 1972, Gómez-Pompa & Kaus 1999, Toledo 1987, Toledo et al. 1995, Sheil & Lawrence 2004, Reyes-Tagle 2007, González-Cruz et al. 2014).

This study aspires to contribute with some methodological elements and insights for linking local medicinal knowledge, values and experiences with ecological research to design strategies for restoration of tropical rain forests. Both ecological and human cultural roles of species deserve to be considered when planning ecological restoration actions. Structural and functional roles of species are important, as well as their role in satisfying local needs and technical experiences for managing the relevant resources. Ethnobotanical and ecological research are both important for recovering resources, their populations and the ecosystems where they occur (Garibaldi & Turner 2004). Particularly important are long-lived trees, which are valuable resources and help to put in perspective long-term conservation and sustainable use actions, which are particularly important in tropical forests (Janzen 1970, Gómez-Pompa et al. 1972, Novotny et al. 2006, Wuethrich 2007, Chazdon 2008).

Due to its identification of medicinal tree species with both cultural and ecological importance should TMK become part of a strategy to be considered in tropical forest restoration actions? Our results show that through TMK we can identify culturally important species for their medicinal uses, we also find that the species that are culturally important are not those considered with priority for their management of propagation and reintroduction in the area for forest restoration. The TMK information shows that regardless of the high values of cultural significance of the species, the criterion for selecting them for restoration is not restricted to the importance of their use, but also, and mainly, to their low availability and the perception of difficulties regarding their natural regeneration.

Our results also provide information on the pressure received by some culturally significant and abundant species (e.g. Gliricidia sepium, Bursera simaruba, Piper auritum, and Cecropia obtusifolia); their wide availability is sustaining increasing use associated to their perceived medicinal value. On the other hand, other species with very low availability have few medicinal uses. We consider that the TMK in particular, as well as TEK when other non-medicinal uses are associated to medicinal trees of the region, are relevant to design local strategies of restoration of tropical forests; it is to be expected that when selecting species of local cultural interest, the long-term ecological restoration actions may be more probably successful due to the involvement of local actors from the early stages of the process.

The role of gender in traditional medicinal knowledge. The highest values of IKR in all communities were recorded among adult and elder women, particularly in Oxolotán, where expert traditional physicians are recognized and, although institutional health services are available, local people still consult them. The localities of Tomás Garrido and La Cumbre have also local experts, mainly for attending births and cultural illnesses. We recorded the lowest number of medicinal trees in the Cerro Blanco community, which could be associated with the ages of the women interviewed, 25 adults and 4 elderly women (see Appendix 1). In addition, it could be due to the particular fact that we were not able to interview any men there that could possibly add to the knowledge of some other species. According to Stagegaard et al. (2002) and Luoga et al. (2000) knowledge of the medicinal flora may be different between men and women, and these authors argue that women have a deeper knowledge of the medicinal properties of herbaceous plants, while men recognize the medicinal attributes of trees and lianas. However, our results show that adult and elderly women have the greatest wealth of knowledge on medicinal tree species detected in this study, contrary to the reports by Stagegaard et al. (2002) and Luoga et al. (2000). Our finding is consistent with the pattern reported in other tropical regions (Kainer & Duryea 1992, Coe & Anderson 1996, Gollin 1997, Begossi et al. 2000, Voeks & Nyawa 2001, Kothari 2003, Voeks 2007). Age is also positively related to a higher TMK, a finding similarly reported by Case et al. (2005), Quinlan & Quinlan (2007), Eyssartier et al. (2008), Silalahi et al. (2015) and Shaheen et al. (2017), among others.

In our study, we observed that women have a relevant role in the preservation of medicinal culture, since they have a high wealth of traditional knowledge about medicinal trees in the region. Adult and elderly women recognize species with medicinal uses as well as their low availability for their use. This knowledge input from women has contributed to the selection of species that can be used in programs to restore the forest cover of the tropical forest of the region.

We report an average IKR value of less than half the total number of medicinal trees registered in this study. The wealth of knowledge about the medicinal uses of native tree species can be considered a reference to the current status of the TMK and may also indicate that the current status of the TMK is possibly eroding in the Maya and Zoque communities of the region. This could have negative implications at the local and regional scales (Albuquerque et al. 2006, Shaheen et al. 2017). This study suggests that the maintenance of TMK in the local communities can be attained by selecting tree species of medicinal interest for forest restoration programs.

We conclude that TMK provides useful criteria for the identification of the cultural significance of the tree species included in this study; it also reflects the interest that local people have in the management of the species, in particular those considered to be high priority for restoration actions of the tropical forest. This traditional knowledge provides information on the uses, cultural values and local experiences of species management, which may be considered useful in a comprehensive analysis of possible restoration actions in tropical forests.

nova página do texto(beta)

nova página do texto(beta)